Volume 14, Issue 2 (Mar & Apr 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(2): 147-160 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khatti-Dizabadi F, Yazdani-Charati J, Fathizadeh S, Mostafavi F, Amani R. Understanding the Factors Influencing Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Behavior of Office Workers: Intervention Strategies Using Social Marketing Techniques Based on Pender’s Health Promotion Model. J Research Health 2024; 14 (2) :147-160

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2260-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2260-en.html

Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi1

, Jamshid Yazdani-Charati2

, Jamshid Yazdani-Charati2

, Shadi Fathizadeh3

, Shadi Fathizadeh3

, Firoozeh Mostafavi4

, Firoozeh Mostafavi4

, Reza Amani5

, Reza Amani5

, Jamshid Yazdani-Charati2

, Jamshid Yazdani-Charati2

, Shadi Fathizadeh3

, Shadi Fathizadeh3

, Firoozeh Mostafavi4

, Firoozeh Mostafavi4

, Reza Amani5

, Reza Amani5

1- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

2- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Health Sciences Research Center, School of Health, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

3- Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, Health Professions Education Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran. Iran.

4- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,mostafavi@hlth.mui.ac.ir

5- Department of Clinical Nutrition, Food Security Research Center, School of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Health Sciences Research Center, School of Health, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

3- Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, Health Professions Education Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran. Iran.

4- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

5- Department of Clinical Nutrition, Food Security Research Center, School of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Keywords: Formative research, Fruit and vegetable, Pender’s health promotion model (HPM), Social marketing, Staff

Full-Text [PDF 877 kb]

(1083 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3343 Views)

Full-Text: (945 Views)

Introduction

Plentiful fruit and vegetable consumption (F&V) is a vital factor in a healthy diet recommended for various reasons, including fibers, low calories, and antioxidant properties, and to prevent cardiovascular diseases [1, 2]. Nearly 8 million premature deaths worldwide are caused by insufficient F&V consumption of less than 800 g per day [3]. The literature review by Abdi et al. also suggested that the F&V intake in Iran was 25% lower than the recommended limit [4]. Another study showed that 70% and 49% of the people living in Mazandaran Province consumed F&V, which is low [5].

In their study, Rekhy et al pointed to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2013 estimate that about 1.7 million (2.8%) [6], and Hjartaker et al noted that about two million deaths occur each year. It is related to a reduction in the consumption of fruit and vegetables [7]. Since F&V protects against a variety of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, many countries encourage their populations to increase their consumption as a public health priority [7, 8] to reduce the incidence of non-communicable diseases through positively changing eating behaviors with healthy foods partly as a consequence of personal and social behavior patterns [9]. At the same time, social marketing is suggested as a potential way to promote healthy eating [10]and healthy eating behaviors, including F&V [11]. The center for disease control and prevention describes social marketing as the use of marketing principles to influence human behavior and promote social health or interests [12]. Since social marketing is an approach rather than a theory and directs intervention development, using theory or model is an essential part of this process [13]. It is essential to use theory or model to understand which factor describes a behavior since social marketing strategies can focus on variables with the highest impact on the intended outcome [14]. Pender’s health promotion model (HPM) is a comprehensive and predictive healthy behavior promotion model with a theoretical framework for discovering the factors affecting health promotion behaviors [15]. Due to this model’s approach toward changing ecological behavior, which takes intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, and social factors into account, it appears to help identify the factors influencing this behavior’s emergence and maintenance [16]. This model considers the factors that affect behavior in the framework of modifiable factors, cognitive-perceptual factors, and variables influencing behavior probability; and since it does not emphasize personal threats, it is used in different stages of life [16]. Meanwhile, since the WHO prioritizes workplaces to present dietary behaviors, they are suitable to implement food interventions [17]. When healthy choices are supported by the environment and policies, the norms and social support for healthy choices are strong and people are encouraged and educated to make healthy choices, their behavior will likely change [18]. Diet is the vital modifiable risk factor for chronic disease [19, 20]. The consumption of fruits and vegetables in the diet is one of the main factors involved in reducing chronic diseases, including coronary artery disease [21-28]. Non-communicable diseases are partly the result of individual and social behaviors, therefore positive changes in healthy nutrition and dietary behaviors may reduce the risk of disease [29, 30]. Secondly, due to the involvement of office workers with risk factors, such as inactivity or long-term replacement during working hours and increased tolerance of stress caused by acceptance of work responsibilities [31], the necessity of a study examining the consumption behavior of fruits and vegetables in a more homogenous society in terms of occupational and social conditions was needed.

Methods

This descriptive study was formative research to determine the effect of organizational social marketing techniques based on Pender’s HPM on F&V consumption in-office staff. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to analyze the target group, channel, and market, also due to the organization of this study, the environment was analyzed in terms of opportunities and obstacles, (e.g. present organizational rules and policies, the participation of the key individual in the developing, implementation, and evaluation of suitable interventions in the organization) and how to engage other related organizations to cooperate and participate to improve F&V consumption behavior in the office staff, to develop strategies based on social marketing. This study was performed in two stages, formative research, and the developing of intervention strategies based on a social marketing mix, also formative research consisted of two steps, qualitative, and quantitative. This study was conducted on employees of a government office (Department of Education) in Ghaemshahr City, Mazandaran Province with a condition of entry (a minimum of 70 staff members) from December 11, 2019, to February 4, 2020.

Sample size

Considering that the present study was the preliminary stage of an interventional study, based on the sample size formula in the intervention study, the sample size was estimated at 70 people, therefore in the quantitative stage, 70 people were included in the study.

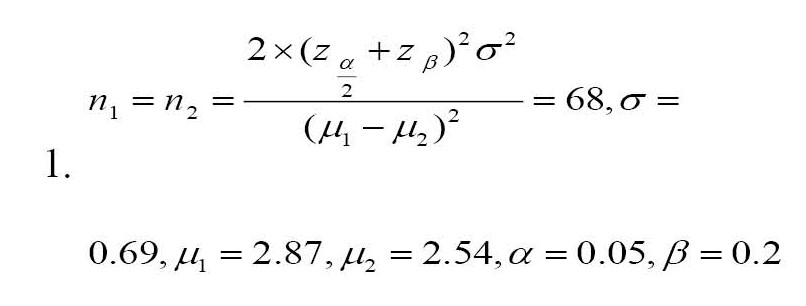

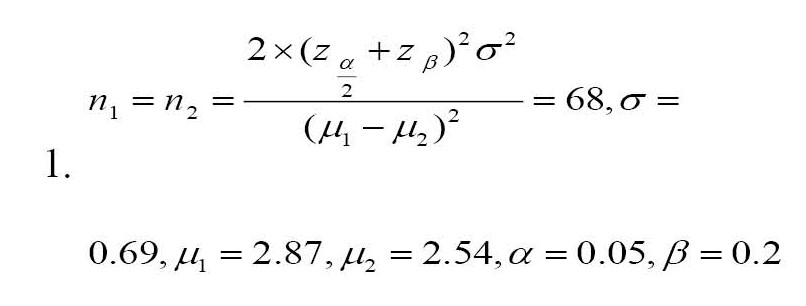

According to the main research variable, i.e. F&V intake, and considering (Equation 1),

The size of each intervention and control group was estimated at 70.

Study participants and sampling

This study was conducted to collect information from employees and officials of the city’s Department of Education on the perception of F&V consumption behavior, barriers to consumption at home and office, and recommend solutions. The Department of Education’s administrative automation was used to call and register individuals to participate in the study and was selected by the convenience sampling method. Since the participants in this stage also had to take part in part two involving an intervention, this stage had to consider the condition for entry into stage two. Therefore, volunteers needed to be employed at the office in question and fill out the consent form. They were also assessed for lack of contradiction to participate in the intervention. Finally, 70 people participated in this study, of which all 70 people participated in the quantitative phase of the study and 36 people participated in the qualitative phase of the study.

Data collection for qualitative analysis

To identify the benefits, barriers, preferences, and facilitators of F&V consumption and preferential communication channels, individual interviews and focus group discussions were conducted with the target group using structured questions, and the necessary observations to obtain the necessary information regarding available opportunities inside and outside the organization.

Individuals were to register and participate in the study first through the call (with the aim of the study and the condition of entering the study) which was sent to all employees using office automation and also face-to-face notification by colleagues in both departments from 11/12/2019 to 29/12/2020 by referring to the administrative affairs department of the municipality and the research unit of the Education Department.

Some of the group discussion questions and interviews were on the following subjects:

1. How do you perceive a person who recommends the use of more F&V? 2. What specific things do you do to encourage coworkers to consume more F&V? 3) What were some of the memorable or interesting programs or activities in the office to motivate you to do certain activities? 4. In your opinion, what factors can affect the reception of F&V consumption? 5. What is the best educational program to provide you an effective training? 6. Which is the best program to cause you to consume more F&V?

Data collection for quantitative analysis

Since developing scientific knowledge of social marketing requires compatible theory application and accurate measurements, and given the target group and the organizational environment of study, Pender’s HPM was used alongside the social marketing approach as it considers personal as well as interpersonal and environmental factors. Therefore, the quantitative section consisted of two separate questionnaires. Researcher-made questionnaire of perception of F&V consumption behavior based on Pender’s HPM, that the results of content validity ratio, the content validity index, and Cronbach’s α of the questionnaire were 0.92,0.97 and 0.96, respectively, and in construct validation by using exploratory factor analysis test comprised 61.14% of the model’s cumulative variance and consisted of 104 items in 12 constructs that included previous related behavior, perceived self-efficacy, behavioral feelings, perceived benefits and barriers, interpersonal effects, situational influencers, motivational factors added to Pender’s HPM, commitment to the action plan, preferences, and immediate demand, and behavioral outcomes in a 5-point Likert scale (zero=none, 4=always) with knowledge questions by selecting the correct answer [32]. The second questionnaire was F&V frequency questionnaire, which consisted of 33 items and was extracted from the validated 86-item food frequency questionnaire, which was used in the study of Veisi et al [33]. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed with the help of nutritionists and the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.71 using the retest. The questionnaire collected data related to the mean consumption of F&V food groups per day according to the amount of each unit mentioned in the questionnaire.

Qualitative data analysis

The researcher recorded all interviews and focus group discussions, followed by word-for-word transcription of interviews for proper coding. In this study, purposive sampling was unlikely and to obtain information, reaching saturation level was considered as the end of sampling. Finally, the initial codes and categories were extracted using the direct content analysis method by MAX QDA software. Then, the codes and categories were re-evaluated with an expert’s help, and the results were written.

Quantitative data analysis

Questionnaire data was analyzed by SPSS software, version 22 using descriptive statistics, and stepwise multiple regression.

Strategy design stage

In the second stage, intervention strategies based on social marketing techniques were designed and organized using the results extracted from the formative research stage with a downstream and midstream approach while considering benchmarks (by integrating Anderson’s six benchmarks and the National Social Marketing Center’s 8 benchmarks) [34, 35], and Pender’s HPM constructs.

Behavior: The goal is to identify clear behaviors for change, not simply to change knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes [13].

Theory: Behavioral theories with identification of factors affecting behaviors, their formation, and their changes in designing interventions [13].

Segmentation of the audience: Identification and meaningful prioritization of the target population regarding the intervention’s objectives according to clear criteria [13].

Exchange: Offering something valuable to the audience to change behavior [34]. Individuals need meaningful motivations to change their attitudes [36].

Customer-orientation: Developing interventions based on the opinions, demands, needs, and preferences of employees [34].

Competition: Knowledge of the products considered by the target audience to select the suitable product [37]. Competitive behaviors are evaluated using interventions, which may be internal, e.g. Current personal behaviors, or external, such as bad policies [34].

Data-based decision making: Compilation of all interventions taking into account the results of formative research (quantitative and qualitative survey) [38].

Marketing mix: The right marketing mix can be essential to a program’s success. When designing a program to determine the best mix for the target group, all four marketing mix elements (product, place, price, and promotion) are analyzed and considered [39]. It is a key concept in social marketing and is defined as a set of adjustable tools that can be combined to respond to the target market and group, and includes 1. The product: The behavior or suggestion that the target audience is expected to accept is a set of benefits and opportunities offered to the customer, and 2. Price: What the target audience sees as the price for accepting the new behavior, 3. Place: Where the consumer has access to products and information and where a voluntary exchange takes place, and 4. Promotion: The process of communicating with the target group about the product [34].

Results

Qualitative phase of formative research

In this study, 12 individual interviews were conducted with 6 men and 6 women, and 3 focus group discussions with a group of female employees, a group of male employees, and a group of management-level employees with 8 participants in each with a mean age of 45±10.2 years and work experience of 6±2.96 years. Based on the results of direct content analysis in the qualitative section, which included interviews and observations, facilitators, internal and external barriers related to F&V consumption behavior, and acceptance of training related to the importance of F&V consumption were extracted in five main categories, including product (with 3 subcategories including core product, actual product, and augmented product, place (with 1 sub-category of structural factors), price (with 4 subcategories, health factors, individual factors, organizational factors and structural factors related to fruit and vegetable consumption and 3 subcategories of structural factors, individual factors, and organizational factors related to the acceptance of health education), promotion and organizational support. Then, the social marketing criteria related to each of these factors were identified (Table 1).

Quantitative phase of formative research

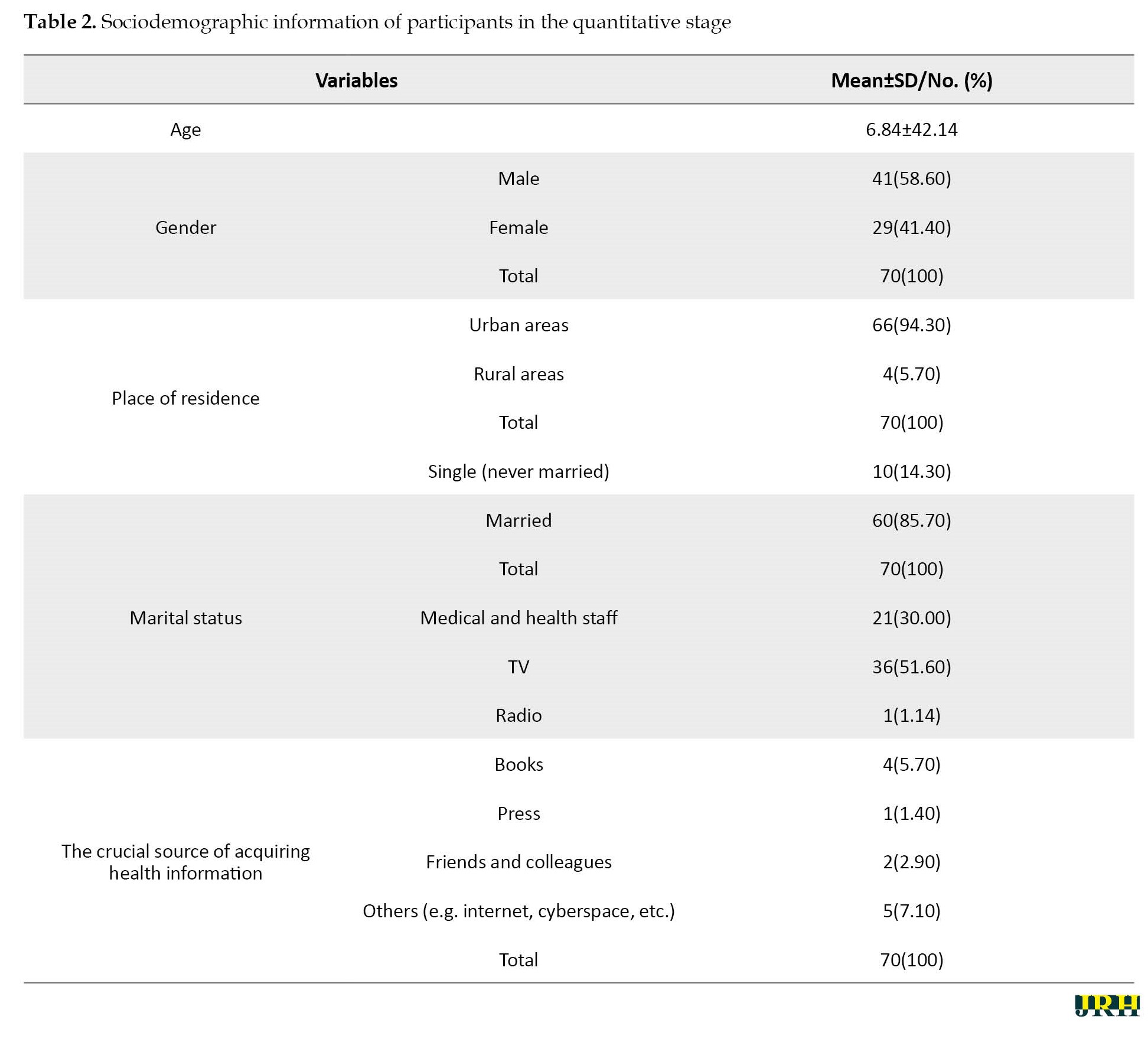

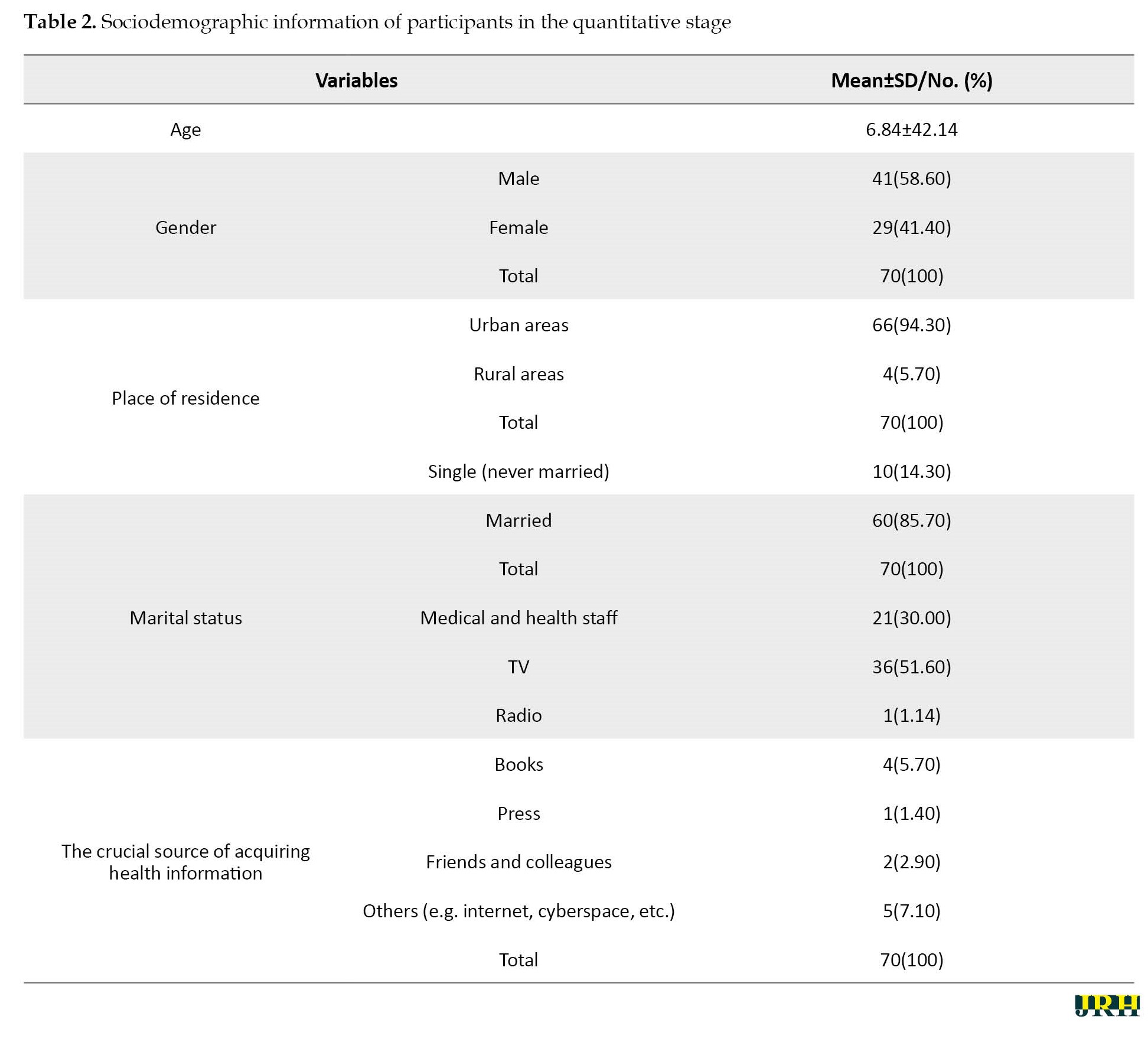

The mean age of participants was 42.14±6.84. The critical way to obtain health information was via television (60.51) and health staff (30.00) (Table 2).

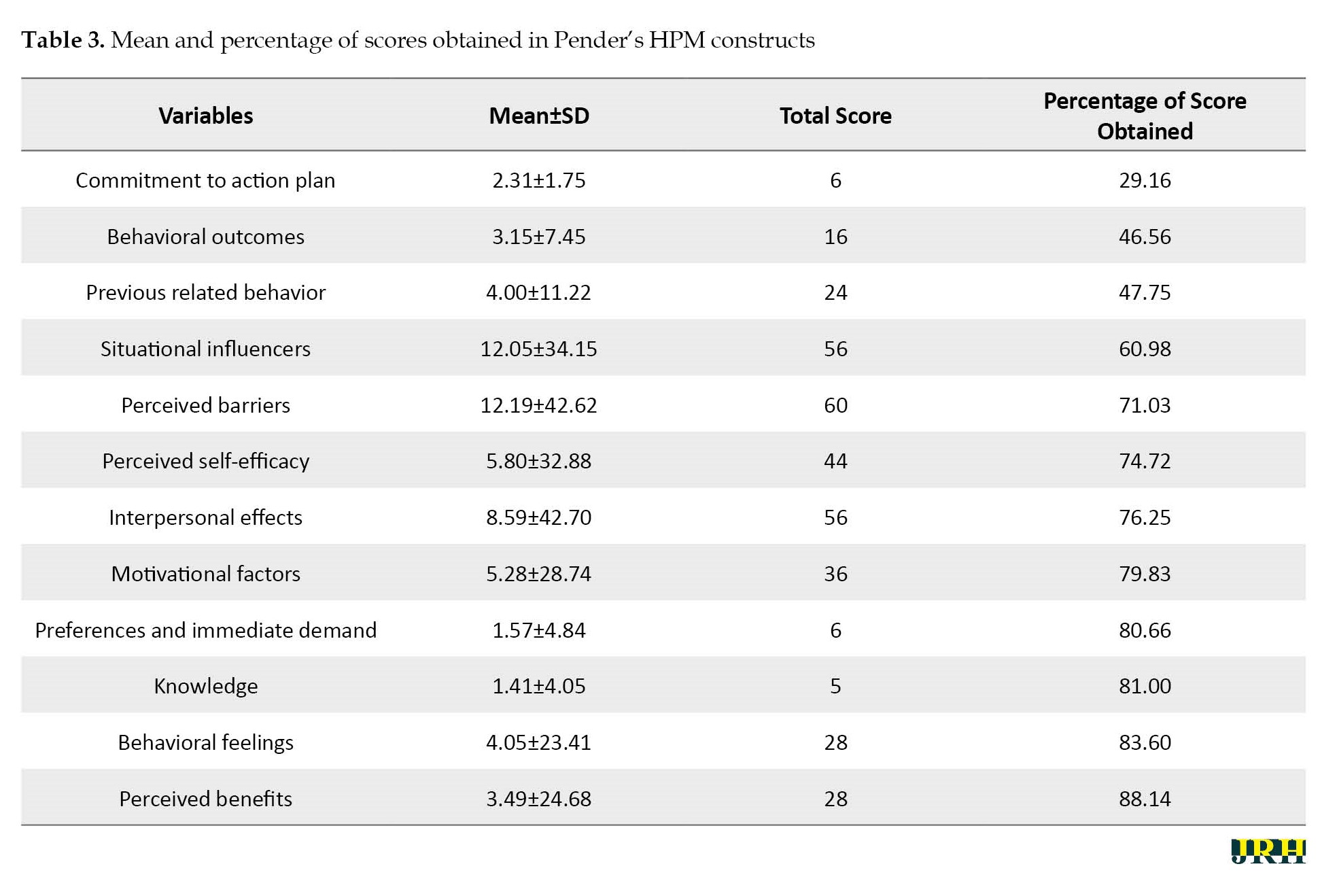

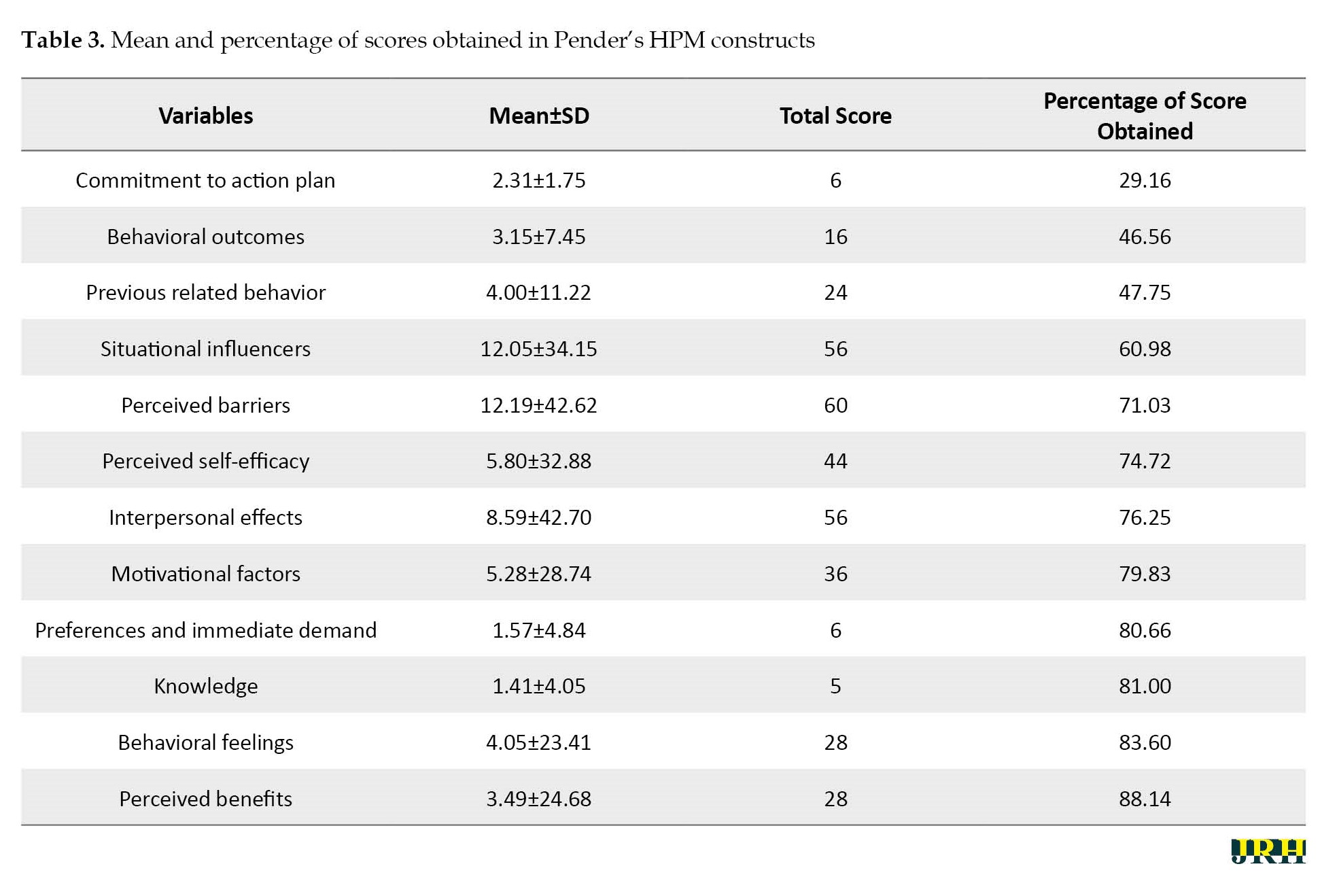

The lowest percentage of mean scores was related to the construct of commitment to the action plan (29.16%), behavioral outcome (46.56%), and previous related behavior with 46.75%, respectively (Table 3).

According to the stepwise multiple linear regression,previous related behaviors and behavioral outcome constructs of Pender’s HPM predicted 38% of F&V consumption behavior (Table 4).

Developing intervention strategies

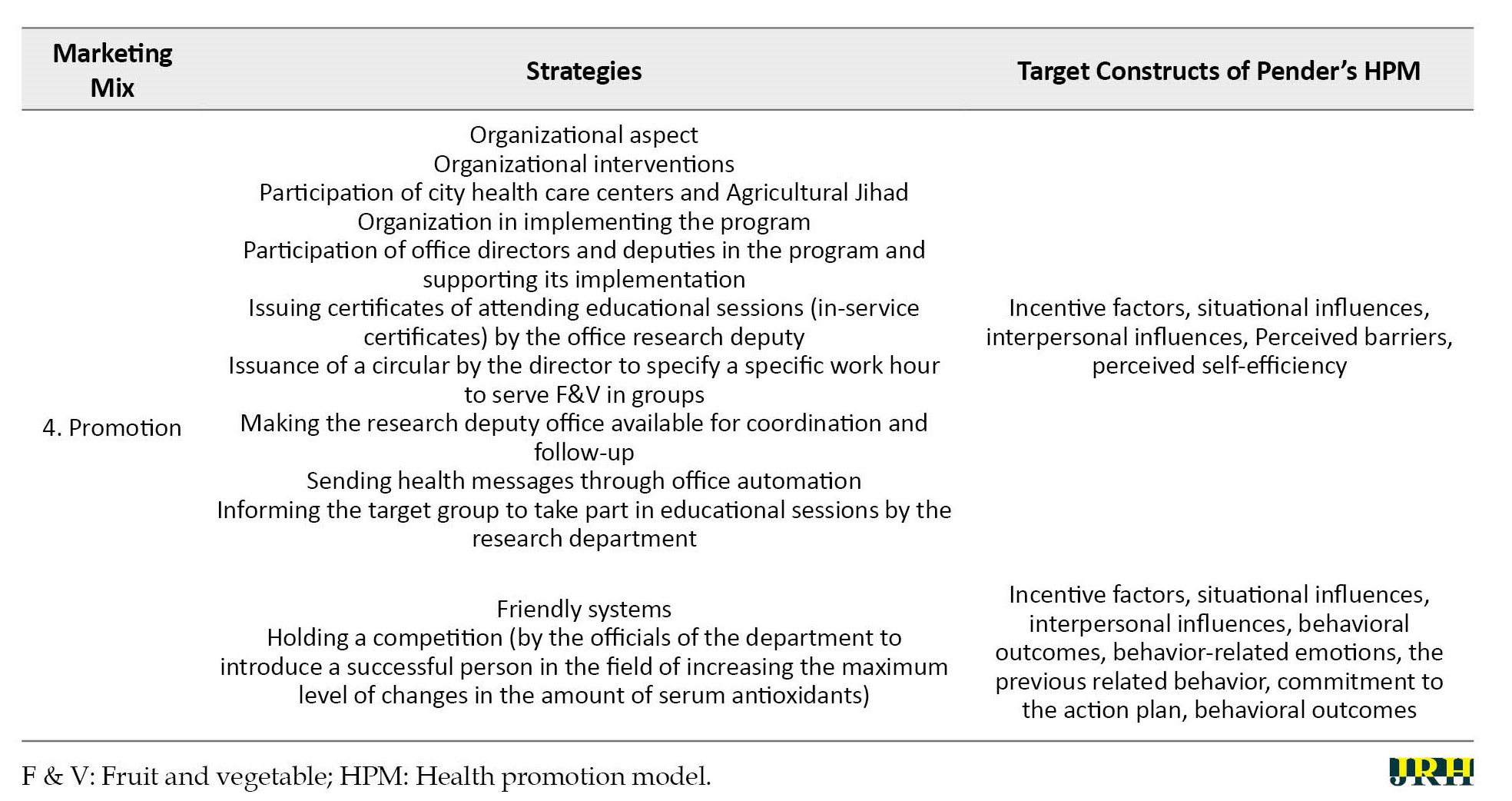

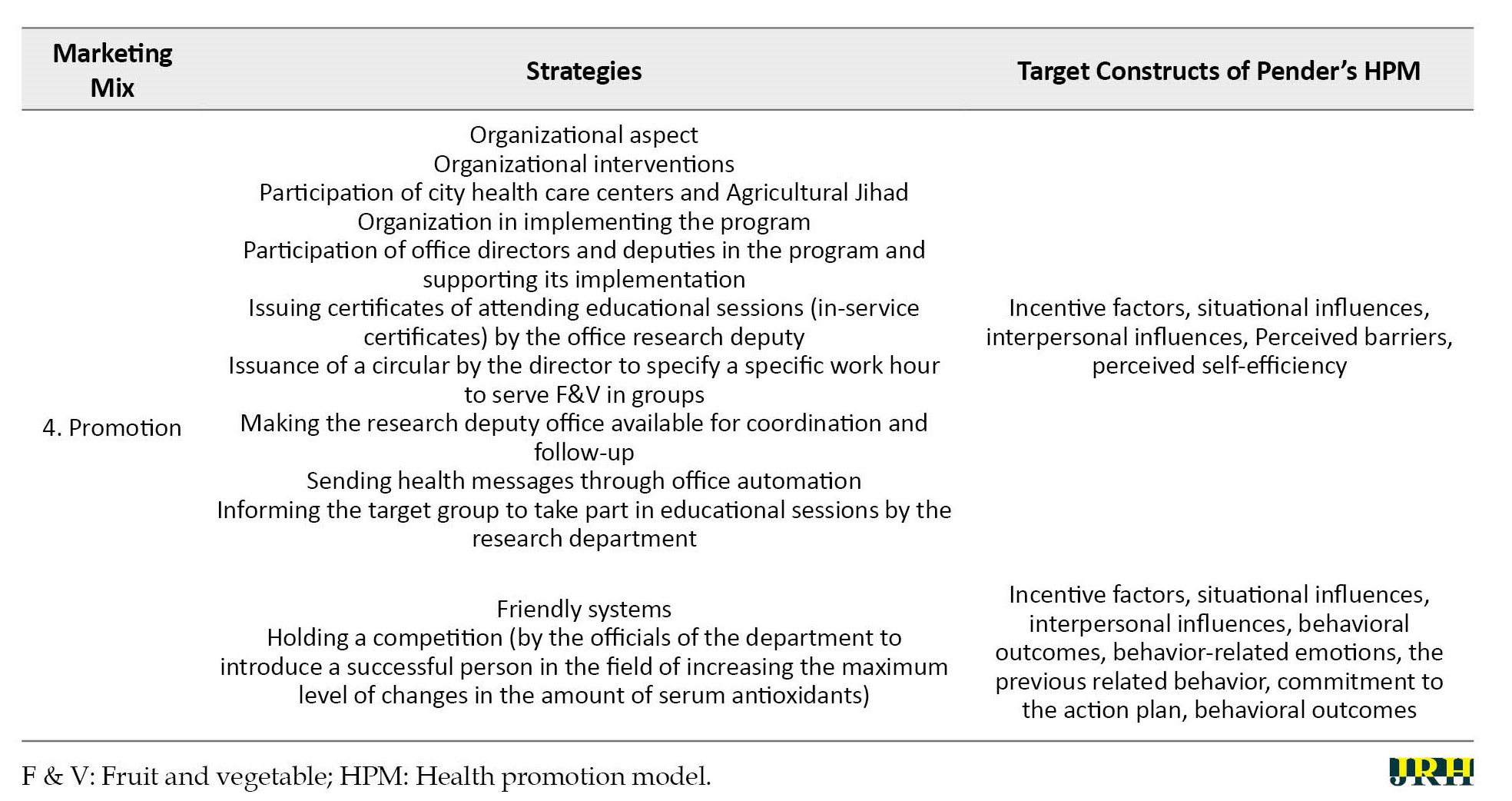

Reinforcement and induction strategies were developed by aggregating the results from the quantitative and qualitative sections with an information approach according to downstream and intermediate social marketing techniques (Table 5).

The present study used the information approach to develop strategies according to the results from formative research in the environment because different approaches are observed in social marketing, downstream approach, midstream approach, and upstream approach. The goal of the downstream approach is to address the problem by facilitating access to solutions [40], where the customer is responsible for changing their behavior [41]. The midstream approach targets individuals who can help change group behavior, e.g. family, friends, and colleagues; and the upstream approach focuses on the main causes of problems [40]. Influencing policy and changing the people’s environment, in other words, on decisions of groups and individuals who affect the target market, including policymakers, media figures, social actors, etc. [42, 43]. Therefore, given the scope, authority, time, and environment, this study employed a hybrid downstream-midstream approach. To achieve its goals, social marketing requires using and coordinating with other approaches, according to Santesmases, these approaches are divided into four groups, the legal approach is determined by rules and regulations, approvals, and executive guarantees; the technological approach is based on technological innovations and facilitates desirable behavior; the economic approach reduces the desired behavior’s cost or increasing the undesirable behavior’s cost to discourage; and the information approach focuses foremost on persuasive and encouraging information [44]. The present study used the information approach to develop strategies according to the results from formative research in the environment.

Kotler and Lee named three categories of products in social marketing, including the core product, the actual product, and the augmented product. The target group will receive the core product’s benefits by performing the desirable behavior. The actual product is the desired behavior that the target group should choose, and the augmented product is the complementary services or a tangible provided to support the desired behavior [45]. The core product of the present study was the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, the actual product was daily F&V consumption with the suggested amount, and finally, the augmented product was education regarding the importance of F&V consumption. According to the qualitative section, most obstacles and problems according to the categorization of content analysis (structural elements, health factors, personal factors, and organizational factors) were related to structural factors of F&V consumption as the actual product, and education about the importance of F&V consumption as the augmented product. Therefore, considering the product’s structural aspect was more crucial to developing strategies. In the qualitative section, the most problematic constructs in the target group corresponded to commitment to the action plan, behavioral consequences, and related previous behavior. In an investigation conducted by Gough et al., the two main barriers to a healthy diet were pessimism about the government’s health messages and rejection. A healthy diet is caused by bad taste and inability to fulfill [46]. Also, in an investigation conducted by Verstraeten et al., the results confirmed the importance of investigating behavioral and environmental factors that influence and mediate healthy eating behaviors before intervention development [47]. In a survey conducted by Kabir et al., dietary behavior and consumption are influenced by a variety of factors, individual factors (cooking skills, food taste, food taboos, and knowledge and perceptions), societal factors (influence of peers and social norms), factors related to university (campus culture and frequency of examination), and environmental factors (availability of cooking resources and facilities and food prices) [48].

According to the theoretical framework of Pender’s HPM, influential factors can increase or decrease health promotion behaviors and occur when other important individuals, or behavior models, expect them, and to perform supportive actions, individuals are expected to be committed to health promotion actions because they act as a behavioral intermediary as well as the actual behavior [49]. Therefore, the research environment and its organizational orientation reveal the importance of using these constructs and their influence, where it is crucial to evaluate the cause of problems and facilitate their improvement. At the same time, related previous behavior, behavioral consequences, and immediate preferences, which predicted F&V consumption behavior, should also be the targets of developing strategies, since previous behaviors, inherited features of beliefs, emotions, and the fixation of health promotion factors, and when other behaviors are more appealing or are not influenced by the competitor’s demands, commitment is less likely to create the intended behavior [49, 50]. Therefore, this study tries to consider these cases in developing all strategies. Most developed strategies were intended to cover present problems in the structural dimension and the most problematic and critical constructs. For example, to increase the interpersonal effects, a strategy was developed to use colleagues’ positive experiences in F&V consumption to target the situational effects of the healthy snack program. Also, the strategies used to cover structures with a higher predictive ability of F&V consumption behavior stressed the benefits of behaviors that increase the mean score of these constructs and consumption behavior, since individuals are committed to behaviors whose personal interests are predictable [50]. Also, since most target group’s health information was obtained from healthcare staff after television, strategies were developed for his group to deliver educational content and messages, since healthcare suppliers are crucial sources of interpersonal interaction that can increase or decrease commitment to health promotion behaviors [49, 50]. Moreover, strategies were developed to mitigate communication obstacles related to health factors of F&V consumption, e.g. fear of chemical toxins used in F&V, the use of agricultural Jihad organization’s experts to correctly transfer information regarding the use of agricultural toxins, amount and time of use, and other factors, to ultimately create value for individuals to access an acceptable personal balance between change and stability [49, 50]. In the next dimension, personal factors, such as strategies were used to empower individuals to consume more F&V, including the strategy of showing how to wash F&V. Enhancing self-efficacy reduce perceived barriers to performing a particular health behavior [49, 50]. Since the results of the F&V frequency questionnaire were lower for the target group than recommended, efforts were made to tailor the reinforcement and inductive strategies to maintain or improve the behavior in question. Regarding the organizational factors, strategies were developed to increase the participation of office authorities in the coordination, design, and implementation of the program, e.g. providing in-service certificates to the target group for their participation in in-person educational sessions. Santesmases introduced four main strategies for social marketing, 1. The reinforcement strategy: With a positive attitude toward the target idea or behavior and the behaviors that are compatible, the strategy’s goal is to reinforce the condition, e.g. giving rewards, economic or non-economic incentives, and legal norms. 2. The enforcement or induction strategy: When the attitude toward the idea or behavior is positive yet the desired social behavior is not formed. This strategy tries to enforce behavior, e.g. through social controls, facilitating material and human resources for the desired behavior, and motivating. 3. Logical strategy: When the desired social behavior is employed yet the attitude toward the behavior is negative. This strategy tries to change attitude to suit the behavior through actions, such as encouragement and control. 4. The exposure strategy: When attitudes and behaviors are compatible but contradictory to the desired social behavior. This strategy is intended to change behavior and attitude, which is the most difficult state to change. This strategy uses economic penalties, mandatory actions, threats, and more [42, 45]. Therefore, given the results of formative research, the suitable strategies for this study were reinforcement and induction strategies, since the results of qualitative analysis of the target group corresponding to F&V consumption were overall positive. Nevertheless, several participants consumed three to five units of F&V a day according to the guidelines, while others, despite their positive attitude toward the behavior, did not have sufficient daily F&V intake.

One of this study’s strengths is its combination of qualitative and quantitative research in the development of strategies. The second is the separate participation of various groups, including women, men, and organizational authorities in focused group discussions and personal interviews. The third strength was the entire target group’s participation in the quantitative stage and the use of two separate standardized questionnaires to obtain a better insight into F&V consumption behavior and the target group’s F&V intake. The study’s crucial limitations include the lack of participation of staff families to obtain important information about the target group for the development of strategies, partial completion of questionnaires through self-representation by the target group, which put its integrity in doubt, and the third limitation regarding the F&V frequency was its evaluation of F&V consumption by the target group over the last six months, making mistakes in recollection of usage frequency in the target group likely. It is suggested that the results and appropriate solutions obtained from this study be available to city officials, such as the governor, and health systems, such as the city health center, which have legal authority and are responsible for the health of people, to develop an operational plan for nutrition in the covered departments, it should be implemented with the focus on fruit and vegetable consumption in the office.

Conclusion

Although social marketing is a planning process, the use of theory can lead to the development of effective marketing strategies. Therefore, social marketing by determining the social marketing approach (downstream, midstream, upstream) can determine the theory or model’s aims and the use of its constructs in research to facilitate people’s perception of the problem in question and develop more accurate strategies by covering all aspects of behavior to take more effective action to improve it.

Suggestions for future studies

To continue the change in nutritional behavior created in the target group that the government employees are in the present study, it is necessary not to neglect the participation of the families of this group because many food groups that may compete with fruit and vegetable consumption among employees should be provided in the home environment for the family to consume in priority. Therefore, to improve behaviors, such as nutritional behaviors that are not only related to work environments, the role of the family should also be considered as a crucial factor and should be included in the study as one of the effective factors in reaching the goal of the study and stronger and more complete strategies should be development based on this factor, therefore it is suggested to plan effectively for family participation and cooperation in future research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1398.465).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Project code: 398521).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Firoozeh Mostafavi and Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi; Methodology: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi, Firoozeh Mostafavi and Jamshid Yazdani-Charati; Investigation: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi, Shadi Fathizadeh, Data collection: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi; Writing the original draft: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi; Review, editing and literature review: Firoozeh Mostafavi and Shadi Fathizadeh; Supervision: Firoozeh Mostafavi, Jamshid Yazdani-Charati and Reza Amani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researcher thanks all professors and government staff who assisted us in this project.

References

Plentiful fruit and vegetable consumption (F&V) is a vital factor in a healthy diet recommended for various reasons, including fibers, low calories, and antioxidant properties, and to prevent cardiovascular diseases [1, 2]. Nearly 8 million premature deaths worldwide are caused by insufficient F&V consumption of less than 800 g per day [3]. The literature review by Abdi et al. also suggested that the F&V intake in Iran was 25% lower than the recommended limit [4]. Another study showed that 70% and 49% of the people living in Mazandaran Province consumed F&V, which is low [5].

In their study, Rekhy et al pointed to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2013 estimate that about 1.7 million (2.8%) [6], and Hjartaker et al noted that about two million deaths occur each year. It is related to a reduction in the consumption of fruit and vegetables [7]. Since F&V protects against a variety of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, many countries encourage their populations to increase their consumption as a public health priority [7, 8] to reduce the incidence of non-communicable diseases through positively changing eating behaviors with healthy foods partly as a consequence of personal and social behavior patterns [9]. At the same time, social marketing is suggested as a potential way to promote healthy eating [10]and healthy eating behaviors, including F&V [11]. The center for disease control and prevention describes social marketing as the use of marketing principles to influence human behavior and promote social health or interests [12]. Since social marketing is an approach rather than a theory and directs intervention development, using theory or model is an essential part of this process [13]. It is essential to use theory or model to understand which factor describes a behavior since social marketing strategies can focus on variables with the highest impact on the intended outcome [14]. Pender’s health promotion model (HPM) is a comprehensive and predictive healthy behavior promotion model with a theoretical framework for discovering the factors affecting health promotion behaviors [15]. Due to this model’s approach toward changing ecological behavior, which takes intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, and social factors into account, it appears to help identify the factors influencing this behavior’s emergence and maintenance [16]. This model considers the factors that affect behavior in the framework of modifiable factors, cognitive-perceptual factors, and variables influencing behavior probability; and since it does not emphasize personal threats, it is used in different stages of life [16]. Meanwhile, since the WHO prioritizes workplaces to present dietary behaviors, they are suitable to implement food interventions [17]. When healthy choices are supported by the environment and policies, the norms and social support for healthy choices are strong and people are encouraged and educated to make healthy choices, their behavior will likely change [18]. Diet is the vital modifiable risk factor for chronic disease [19, 20]. The consumption of fruits and vegetables in the diet is one of the main factors involved in reducing chronic diseases, including coronary artery disease [21-28]. Non-communicable diseases are partly the result of individual and social behaviors, therefore positive changes in healthy nutrition and dietary behaviors may reduce the risk of disease [29, 30]. Secondly, due to the involvement of office workers with risk factors, such as inactivity or long-term replacement during working hours and increased tolerance of stress caused by acceptance of work responsibilities [31], the necessity of a study examining the consumption behavior of fruits and vegetables in a more homogenous society in terms of occupational and social conditions was needed.

Methods

This descriptive study was formative research to determine the effect of organizational social marketing techniques based on Pender’s HPM on F&V consumption in-office staff. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to analyze the target group, channel, and market, also due to the organization of this study, the environment was analyzed in terms of opportunities and obstacles, (e.g. present organizational rules and policies, the participation of the key individual in the developing, implementation, and evaluation of suitable interventions in the organization) and how to engage other related organizations to cooperate and participate to improve F&V consumption behavior in the office staff, to develop strategies based on social marketing. This study was performed in two stages, formative research, and the developing of intervention strategies based on a social marketing mix, also formative research consisted of two steps, qualitative, and quantitative. This study was conducted on employees of a government office (Department of Education) in Ghaemshahr City, Mazandaran Province with a condition of entry (a minimum of 70 staff members) from December 11, 2019, to February 4, 2020.

Sample size

Considering that the present study was the preliminary stage of an interventional study, based on the sample size formula in the intervention study, the sample size was estimated at 70 people, therefore in the quantitative stage, 70 people were included in the study.

According to the main research variable, i.e. F&V intake, and considering (Equation 1),

The size of each intervention and control group was estimated at 70.

Study participants and sampling

This study was conducted to collect information from employees and officials of the city’s Department of Education on the perception of F&V consumption behavior, barriers to consumption at home and office, and recommend solutions. The Department of Education’s administrative automation was used to call and register individuals to participate in the study and was selected by the convenience sampling method. Since the participants in this stage also had to take part in part two involving an intervention, this stage had to consider the condition for entry into stage two. Therefore, volunteers needed to be employed at the office in question and fill out the consent form. They were also assessed for lack of contradiction to participate in the intervention. Finally, 70 people participated in this study, of which all 70 people participated in the quantitative phase of the study and 36 people participated in the qualitative phase of the study.

Data collection for qualitative analysis

To identify the benefits, barriers, preferences, and facilitators of F&V consumption and preferential communication channels, individual interviews and focus group discussions were conducted with the target group using structured questions, and the necessary observations to obtain the necessary information regarding available opportunities inside and outside the organization.

Individuals were to register and participate in the study first through the call (with the aim of the study and the condition of entering the study) which was sent to all employees using office automation and also face-to-face notification by colleagues in both departments from 11/12/2019 to 29/12/2020 by referring to the administrative affairs department of the municipality and the research unit of the Education Department.

Some of the group discussion questions and interviews were on the following subjects:

1. How do you perceive a person who recommends the use of more F&V? 2. What specific things do you do to encourage coworkers to consume more F&V? 3) What were some of the memorable or interesting programs or activities in the office to motivate you to do certain activities? 4. In your opinion, what factors can affect the reception of F&V consumption? 5. What is the best educational program to provide you an effective training? 6. Which is the best program to cause you to consume more F&V?

Data collection for quantitative analysis

Since developing scientific knowledge of social marketing requires compatible theory application and accurate measurements, and given the target group and the organizational environment of study, Pender’s HPM was used alongside the social marketing approach as it considers personal as well as interpersonal and environmental factors. Therefore, the quantitative section consisted of two separate questionnaires. Researcher-made questionnaire of perception of F&V consumption behavior based on Pender’s HPM, that the results of content validity ratio, the content validity index, and Cronbach’s α of the questionnaire were 0.92,0.97 and 0.96, respectively, and in construct validation by using exploratory factor analysis test comprised 61.14% of the model’s cumulative variance and consisted of 104 items in 12 constructs that included previous related behavior, perceived self-efficacy, behavioral feelings, perceived benefits and barriers, interpersonal effects, situational influencers, motivational factors added to Pender’s HPM, commitment to the action plan, preferences, and immediate demand, and behavioral outcomes in a 5-point Likert scale (zero=none, 4=always) with knowledge questions by selecting the correct answer [32]. The second questionnaire was F&V frequency questionnaire, which consisted of 33 items and was extracted from the validated 86-item food frequency questionnaire, which was used in the study of Veisi et al [33]. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed with the help of nutritionists and the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.71 using the retest. The questionnaire collected data related to the mean consumption of F&V food groups per day according to the amount of each unit mentioned in the questionnaire.

Qualitative data analysis

The researcher recorded all interviews and focus group discussions, followed by word-for-word transcription of interviews for proper coding. In this study, purposive sampling was unlikely and to obtain information, reaching saturation level was considered as the end of sampling. Finally, the initial codes and categories were extracted using the direct content analysis method by MAX QDA software. Then, the codes and categories were re-evaluated with an expert’s help, and the results were written.

Quantitative data analysis

Questionnaire data was analyzed by SPSS software, version 22 using descriptive statistics, and stepwise multiple regression.

Strategy design stage

In the second stage, intervention strategies based on social marketing techniques were designed and organized using the results extracted from the formative research stage with a downstream and midstream approach while considering benchmarks (by integrating Anderson’s six benchmarks and the National Social Marketing Center’s 8 benchmarks) [34, 35], and Pender’s HPM constructs.

Behavior: The goal is to identify clear behaviors for change, not simply to change knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes [13].

Theory: Behavioral theories with identification of factors affecting behaviors, their formation, and their changes in designing interventions [13].

Segmentation of the audience: Identification and meaningful prioritization of the target population regarding the intervention’s objectives according to clear criteria [13].

Exchange: Offering something valuable to the audience to change behavior [34]. Individuals need meaningful motivations to change their attitudes [36].

Customer-orientation: Developing interventions based on the opinions, demands, needs, and preferences of employees [34].

Competition: Knowledge of the products considered by the target audience to select the suitable product [37]. Competitive behaviors are evaluated using interventions, which may be internal, e.g. Current personal behaviors, or external, such as bad policies [34].

Data-based decision making: Compilation of all interventions taking into account the results of formative research (quantitative and qualitative survey) [38].

Marketing mix: The right marketing mix can be essential to a program’s success. When designing a program to determine the best mix for the target group, all four marketing mix elements (product, place, price, and promotion) are analyzed and considered [39]. It is a key concept in social marketing and is defined as a set of adjustable tools that can be combined to respond to the target market and group, and includes 1. The product: The behavior or suggestion that the target audience is expected to accept is a set of benefits and opportunities offered to the customer, and 2. Price: What the target audience sees as the price for accepting the new behavior, 3. Place: Where the consumer has access to products and information and where a voluntary exchange takes place, and 4. Promotion: The process of communicating with the target group about the product [34].

Results

Qualitative phase of formative research

In this study, 12 individual interviews were conducted with 6 men and 6 women, and 3 focus group discussions with a group of female employees, a group of male employees, and a group of management-level employees with 8 participants in each with a mean age of 45±10.2 years and work experience of 6±2.96 years. Based on the results of direct content analysis in the qualitative section, which included interviews and observations, facilitators, internal and external barriers related to F&V consumption behavior, and acceptance of training related to the importance of F&V consumption were extracted in five main categories, including product (with 3 subcategories including core product, actual product, and augmented product, place (with 1 sub-category of structural factors), price (with 4 subcategories, health factors, individual factors, organizational factors and structural factors related to fruit and vegetable consumption and 3 subcategories of structural factors, individual factors, and organizational factors related to the acceptance of health education), promotion and organizational support. Then, the social marketing criteria related to each of these factors were identified (Table 1).

Quantitative phase of formative research

The mean age of participants was 42.14±6.84. The critical way to obtain health information was via television (60.51) and health staff (30.00) (Table 2).

The lowest percentage of mean scores was related to the construct of commitment to the action plan (29.16%), behavioral outcome (46.56%), and previous related behavior with 46.75%, respectively (Table 3).

According to the stepwise multiple linear regression,previous related behaviors and behavioral outcome constructs of Pender’s HPM predicted 38% of F&V consumption behavior (Table 4).

Developing intervention strategies

Reinforcement and induction strategies were developed by aggregating the results from the quantitative and qualitative sections with an information approach according to downstream and intermediate social marketing techniques (Table 5).

The present study used the information approach to develop strategies according to the results from formative research in the environment because different approaches are observed in social marketing, downstream approach, midstream approach, and upstream approach. The goal of the downstream approach is to address the problem by facilitating access to solutions [40], where the customer is responsible for changing their behavior [41]. The midstream approach targets individuals who can help change group behavior, e.g. family, friends, and colleagues; and the upstream approach focuses on the main causes of problems [40]. Influencing policy and changing the people’s environment, in other words, on decisions of groups and individuals who affect the target market, including policymakers, media figures, social actors, etc. [42, 43]. Therefore, given the scope, authority, time, and environment, this study employed a hybrid downstream-midstream approach. To achieve its goals, social marketing requires using and coordinating with other approaches, according to Santesmases, these approaches are divided into four groups, the legal approach is determined by rules and regulations, approvals, and executive guarantees; the technological approach is based on technological innovations and facilitates desirable behavior; the economic approach reduces the desired behavior’s cost or increasing the undesirable behavior’s cost to discourage; and the information approach focuses foremost on persuasive and encouraging information [44]. The present study used the information approach to develop strategies according to the results from formative research in the environment.

Kotler and Lee named three categories of products in social marketing, including the core product, the actual product, and the augmented product. The target group will receive the core product’s benefits by performing the desirable behavior. The actual product is the desired behavior that the target group should choose, and the augmented product is the complementary services or a tangible provided to support the desired behavior [45]. The core product of the present study was the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, the actual product was daily F&V consumption with the suggested amount, and finally, the augmented product was education regarding the importance of F&V consumption. According to the qualitative section, most obstacles and problems according to the categorization of content analysis (structural elements, health factors, personal factors, and organizational factors) were related to structural factors of F&V consumption as the actual product, and education about the importance of F&V consumption as the augmented product. Therefore, considering the product’s structural aspect was more crucial to developing strategies. In the qualitative section, the most problematic constructs in the target group corresponded to commitment to the action plan, behavioral consequences, and related previous behavior. In an investigation conducted by Gough et al., the two main barriers to a healthy diet were pessimism about the government’s health messages and rejection. A healthy diet is caused by bad taste and inability to fulfill [46]. Also, in an investigation conducted by Verstraeten et al., the results confirmed the importance of investigating behavioral and environmental factors that influence and mediate healthy eating behaviors before intervention development [47]. In a survey conducted by Kabir et al., dietary behavior and consumption are influenced by a variety of factors, individual factors (cooking skills, food taste, food taboos, and knowledge and perceptions), societal factors (influence of peers and social norms), factors related to university (campus culture and frequency of examination), and environmental factors (availability of cooking resources and facilities and food prices) [48].

According to the theoretical framework of Pender’s HPM, influential factors can increase or decrease health promotion behaviors and occur when other important individuals, or behavior models, expect them, and to perform supportive actions, individuals are expected to be committed to health promotion actions because they act as a behavioral intermediary as well as the actual behavior [49]. Therefore, the research environment and its organizational orientation reveal the importance of using these constructs and their influence, where it is crucial to evaluate the cause of problems and facilitate their improvement. At the same time, related previous behavior, behavioral consequences, and immediate preferences, which predicted F&V consumption behavior, should also be the targets of developing strategies, since previous behaviors, inherited features of beliefs, emotions, and the fixation of health promotion factors, and when other behaviors are more appealing or are not influenced by the competitor’s demands, commitment is less likely to create the intended behavior [49, 50]. Therefore, this study tries to consider these cases in developing all strategies. Most developed strategies were intended to cover present problems in the structural dimension and the most problematic and critical constructs. For example, to increase the interpersonal effects, a strategy was developed to use colleagues’ positive experiences in F&V consumption to target the situational effects of the healthy snack program. Also, the strategies used to cover structures with a higher predictive ability of F&V consumption behavior stressed the benefits of behaviors that increase the mean score of these constructs and consumption behavior, since individuals are committed to behaviors whose personal interests are predictable [50]. Also, since most target group’s health information was obtained from healthcare staff after television, strategies were developed for his group to deliver educational content and messages, since healthcare suppliers are crucial sources of interpersonal interaction that can increase or decrease commitment to health promotion behaviors [49, 50]. Moreover, strategies were developed to mitigate communication obstacles related to health factors of F&V consumption, e.g. fear of chemical toxins used in F&V, the use of agricultural Jihad organization’s experts to correctly transfer information regarding the use of agricultural toxins, amount and time of use, and other factors, to ultimately create value for individuals to access an acceptable personal balance between change and stability [49, 50]. In the next dimension, personal factors, such as strategies were used to empower individuals to consume more F&V, including the strategy of showing how to wash F&V. Enhancing self-efficacy reduce perceived barriers to performing a particular health behavior [49, 50]. Since the results of the F&V frequency questionnaire were lower for the target group than recommended, efforts were made to tailor the reinforcement and inductive strategies to maintain or improve the behavior in question. Regarding the organizational factors, strategies were developed to increase the participation of office authorities in the coordination, design, and implementation of the program, e.g. providing in-service certificates to the target group for their participation in in-person educational sessions. Santesmases introduced four main strategies for social marketing, 1. The reinforcement strategy: With a positive attitude toward the target idea or behavior and the behaviors that are compatible, the strategy’s goal is to reinforce the condition, e.g. giving rewards, economic or non-economic incentives, and legal norms. 2. The enforcement or induction strategy: When the attitude toward the idea or behavior is positive yet the desired social behavior is not formed. This strategy tries to enforce behavior, e.g. through social controls, facilitating material and human resources for the desired behavior, and motivating. 3. Logical strategy: When the desired social behavior is employed yet the attitude toward the behavior is negative. This strategy tries to change attitude to suit the behavior through actions, such as encouragement and control. 4. The exposure strategy: When attitudes and behaviors are compatible but contradictory to the desired social behavior. This strategy is intended to change behavior and attitude, which is the most difficult state to change. This strategy uses economic penalties, mandatory actions, threats, and more [42, 45]. Therefore, given the results of formative research, the suitable strategies for this study were reinforcement and induction strategies, since the results of qualitative analysis of the target group corresponding to F&V consumption were overall positive. Nevertheless, several participants consumed three to five units of F&V a day according to the guidelines, while others, despite their positive attitude toward the behavior, did not have sufficient daily F&V intake.

One of this study’s strengths is its combination of qualitative and quantitative research in the development of strategies. The second is the separate participation of various groups, including women, men, and organizational authorities in focused group discussions and personal interviews. The third strength was the entire target group’s participation in the quantitative stage and the use of two separate standardized questionnaires to obtain a better insight into F&V consumption behavior and the target group’s F&V intake. The study’s crucial limitations include the lack of participation of staff families to obtain important information about the target group for the development of strategies, partial completion of questionnaires through self-representation by the target group, which put its integrity in doubt, and the third limitation regarding the F&V frequency was its evaluation of F&V consumption by the target group over the last six months, making mistakes in recollection of usage frequency in the target group likely. It is suggested that the results and appropriate solutions obtained from this study be available to city officials, such as the governor, and health systems, such as the city health center, which have legal authority and are responsible for the health of people, to develop an operational plan for nutrition in the covered departments, it should be implemented with the focus on fruit and vegetable consumption in the office.

Conclusion

Although social marketing is a planning process, the use of theory can lead to the development of effective marketing strategies. Therefore, social marketing by determining the social marketing approach (downstream, midstream, upstream) can determine the theory or model’s aims and the use of its constructs in research to facilitate people’s perception of the problem in question and develop more accurate strategies by covering all aspects of behavior to take more effective action to improve it.

Suggestions for future studies

To continue the change in nutritional behavior created in the target group that the government employees are in the present study, it is necessary not to neglect the participation of the families of this group because many food groups that may compete with fruit and vegetable consumption among employees should be provided in the home environment for the family to consume in priority. Therefore, to improve behaviors, such as nutritional behaviors that are not only related to work environments, the role of the family should also be considered as a crucial factor and should be included in the study as one of the effective factors in reaching the goal of the study and stronger and more complete strategies should be development based on this factor, therefore it is suggested to plan effectively for family participation and cooperation in future research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1398.465).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Project code: 398521).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Firoozeh Mostafavi and Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi; Methodology: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi, Firoozeh Mostafavi and Jamshid Yazdani-Charati; Investigation: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi, Shadi Fathizadeh, Data collection: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi; Writing the original draft: Freshteh Khatti-Dizabadi; Review, editing and literature review: Firoozeh Mostafavi and Shadi Fathizadeh; Supervision: Firoozeh Mostafavi, Jamshid Yazdani-Charati and Reza Amani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researcher thanks all professors and government staff who assisted us in this project.

References

- Wu QJ, Wu L, Zheng LQ, Xu X, Ji C, Gong TT. Consumption of fruit and vegetables reduces risk of pancreatic cancer: Evidence from epidemiological studies. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016; 25(3):196-205. [DOI:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000171] [PMID]

- Sánchez M, Romero M, Gómez-Guzmán M, Tamargo J, Pérez-Vizcaino F, Duarte J. Cardiovascular effects of flavonoids. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2019; 26(39):6991-7034. [DOI:10.2174/0929867326666181220094721] [PMID]

- Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, Fadnes LT, Keum N, Norat T, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of all cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2017; 46(3):1029-56. [DOI:10.1093/ije/dyw319] [PMID]

- Abdi F, Atarodi Z, Mirmiran P, Esteki T. [Surveying global and Iranian food consumption patterns: A review of the literature (Persian)]. Journal of Advanced Biomedical Sciences. 2015; 5(2):159-67. [Link]

- Djalalinia S, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Sheidaei A, Rezaei N, Naghibi Iravani SS, Modirian M, et al. Patterns of Obesity and Overweight in Iranian Population: Findings of STEPs. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020; 11:42. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2020.00042] [PMID]

- Rekhy R, McConchie R. Promoting consumption of fruit and vegetables for better health. Have campaigns delivered on the goals? Appetite. 2014; 79:113-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.012] [PMID]

- Hjartåker A, Knudsen MD, Tretli S, Weiderpass E. Consumption of berries, fruits and vegetables and mortality among 10,000 Norwegian men followed for four decades. European Journal of Nutrition. 2015; 54(4):599-608. [PMID]

- Silva FM, Smith-Menezes A, Duarte Mde F. Consumption of fruits and vegetables associated with other risk behaviors among adolescents in Northeast Brazil. Revista Paulista de Pediatria. 2016; 34(3):309-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.rpped.2015.09.002] [PMID]

- Cannoosamy K, Pem D, Bhagwant S, Jeewon R. Is a nutrition education intervention associated with a higher intake of fruit and vegetables and improved nutritional knowledge among housewives in Mauritius? Nutrients. 2016; 8(12):723. [DOI:10.3390/nu8120723] [PMID]

- Aschemann-Witzel J, Perez-Cueto FJ, Niedzwiedzka B, Verbeke W, Bech-Larsen T. Lessons for public health campaigns from analysing commercial food marketing success factors: A case study. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:139.[DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-139] [PMID]

- Carins JE, Rundle-Thiele SR. Eating for the better: A social marketing review (2000-2012). Public Health Nutrition. 2014; 17(7):1628-39. [DOI:10.1017/S1368980013001365] [PMID]

- Cheng H, Kotler P, Lee N. Social marketing for public health: Global trends and success stories. Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2010. [Link]

- Luecking CT, Hennink-Kaminski H, Ihekweazu C, Vaughn A, Mazzucca S, Ward DS. Social marketing approaches to nutrition and physical activity interventions in early care and education centers: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2017; 18(12):1425-38. [DOI:10.1111/obr.12596] [PMID]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: Reactions and reflections. Psychology& Health. 2011; 26(9):1113-27. [PMID]

- Wu TY, Pender N. Determinants of physical activity among Taiwanese adolescents: An application of the health promotion model. Research in Nursing & Health. 2002; 25(1):25-36. [DOI:10.1002/nur.10021] [PMID]

- Pender NJ, Murdaugh C, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. London: Pearson; 2006. [Link]

- WHO. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable disease 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Link]

- Linda B, Josephine P, Marie-Louise F. Social marketing’s consumer myopia: Applying a behavioral ecological model to address wicked problems. Journal of Social Marketing. 2016; 6(3):219-39. [Link]

- Choi SE, Seligman H, Basu S. Cost effectiveness of subsidizing fruit and vegetable purchases through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017; 52(5):e147-55. [PMID]

- Vinther JL, Conklin AI, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Marital transitions and associated changes in fruit and vegetable intake: Findings from the population-based prospective EPIC-Norfolk cohort, UK. Social Science & Medicine. 2016; 157:120-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.004] [PMID]

- Kushida O, Murayama N. Effects of environmental intervention in workplace cafeterias on vegetable consumption by male workers. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2014; 46(5):350-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2014.05.001] [PMID]

- Thi CA, Horton KD, Loyo J, Jowers EM, Rodgers LF, Smiley AW, et al. Peer Reviewed: Farm to Work: Development of a modified community-supported agriculture model at worksites, 2007-2012. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2015; 12:E181.[DOI:10.5888/pcd12.150022] [PMID]

- Buil-Cosiales P, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ruiz-Canela M, Díez-Espino J, García-Arellano A, Toledo E. Consumption of fruit or fiber-fruit decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Mediterranean young cohort. Nutrients. 2017; 9(3):295. [DOI:10.3390/nu9030295] [PMID]

- Bandoni DH, Sarno F, Jaime PC. Impact of an intervention on the availability and consumption of fruits and vegetables in the workplace. Public Health Nutrition. 2011; 14(6):975-81. [PMID]

- Kushida O, Iriyama Y, Murayama N, Saito T, Yoshita K. Associations of self-efficacy, social support, and knowledge with fruit and vegetable consumption in Japanese workers. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017; 26(4):725-30. [PMID]

- Risica PM, Gorham G, Dionne L, Nardi W, Ng D, Middler R, al e. A multi-level intervention in worksites to increase fruit and vegetable access and intake: Rationale, design and methods of the ‘Good to Go’cluster randomized trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2018; 65:87-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.cct.2017.12.002] [PMID]

- Silva DA, Silva RJ. Association between physical activity level and consumption of fruit and vegetables among adolescents in northeast Brazil. Revista Paulista de Pediatria. 2015; 33(2):167-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.rpped.2014.09.003]

- Backman D, Gonzaga G, Sugerman S, Francis D, Cook S. Effect of fresh fruit availability at worksites on the fruit and vegetable consumption of low-wage employees. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2011; 43(4):S113-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2011.04.003] [PMID]

- Bundala N, Kinabo J, Jumbe T, Bonatti M, Rybak C, Sieber S. Gaps in knowledge and practice on dietary consumption among rural farming households; a call for nutrition education training in Tanzania. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2020; 71(3):341-51. [PMID]

- Everett BM, Cook NR, Magnone MC, Bobadilla M, Kim E, Rifai N, al al. Sensitive cardiac troponin T assay and the risk of incident cardiovascular disease in women with and without diabetes mellitus: The Women’s Health Study. Circulation. 2011; 123(24):2811-8. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009928] [PMID]

- Hendriksen IJ, Snoijer M, de Kok BP, van Vilsteren J, Hofstetter H. Effectiveness of a multilevel workplace health promotion program on vitality, health, and work-related outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2016; 58(6):575-83. [DOI:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000747] [PMID]

- Khatti-Dizabadi F, Yazdani-Charati J, Amani R, Mostafavi F. Validation of an instrument for perceived factors affecting fruit and vegetable intake based on pender’s health promotion model. Journal of Nutritional Science. 2022; 11:e7. [PMID]

- Veissi M, Anari R, Amani R, Shahbazian H, Latifi SM. Mediterranean diet and metabolic syndrome prevalence in type 2 diabetes patients in Ahvaz, southwest of Iran. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. 2016; 10(2 Suppl 1):S26-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.dsx.2016.01.015] [PMID]

- Andreasen AR. Marketing social marketing in the social change marketplace. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2002; 21(1):3-13. [DOI:10.1509/jppm.21.1.3.17602]

- National Social Marketing Centre. Social marketing benchmark criteria. UK: National Social Marketing; Centre 2010. [Link]

- Lee NR, Kotler Ph. Social marketing: Changing behaviors for good. California: SAGE Publications; 2015. [Link]

- Kotler P, Armstrong GM, Saunders J, Armstrong G. Principles of marketing. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2010. [Link]

- Ramezan M, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Tahmasebinejad Z, Azizi F. Mediterranean dietary patterns and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2019; 25(12):896-904. [Lik]

- Hung CL. A meta-analysis of the evaluations of social marketing interventions addressing smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and eating [PhD disssertation]. Indiana: Indiana University; 2017. [Link]

- Donovan R, Henley N. Principles and practice of social marketing: An internationalperspective.Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress; 2010. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511761751]

- Wood M. Midstream social marketing and the co-creation of public services.Journal of Social Marketing. 2016; 6:277-93. [DOI:10.1108/JSOCM-05-2015-0025]

- Gordon R. Unlocking the potential of upstream social marketing. European Journal of Marketing. 2013; 47( 9):1525-47. [DOI:10.1108/EJM-09-2011-0523]

- Kotler P, Lee N. Social marketing: Influencing behaviors for good. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc; 2008. [Link]

- Santesmases Mestre M. Marketing: conceptos y estrategias. 1993.

- Flora JA, Schooler C, Pierson RM. Effective health promotion among communities of color: The potential of social marketing. In: Goldberg ME, Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE, editors. Social marketing. Theoretical and practical perspectives. London: Psychology Press;1997. [Link]

- Gough B, Conner MT. Barriers to healthy eating amongst men: A qualitative analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2006; 62(2):387-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.032] [PMID]

- Verstraeten R, Van Royen K, Ochoa-Avilés A, Penafiel D, Holdsworth M, Donoso S, et al. A conceptual framework for healthy eating behavior in Ecuadorian adolescents: A qualitative study. Plos One. 2014; 9(1):e87183. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0087183] [PMID]

- Kabir A, Miah S, Islam A. Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Plos One. 2018; 13(6):e0198801. [PMID]

- Velema E, Vyth EL, Steenhuis IH. Using nudging and social marketing techniques to create healthy worksite cafeterias in the Netherlands: Intervention development and study design. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17(1):63. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-016-3927-7] [PMID]

- Saffari M, ShoJaeezadeh D. Theories, models, and methods of health education and health promotion. Tehran: Asar-E Sobhan Publishing; 2009. [Link]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Health Education

Received: 2023/01/29 | Accepted: 2023/06/20 | Published: 2024/03/1

Received: 2023/01/29 | Accepted: 2023/06/20 | Published: 2024/03/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |