Volume 13, Issue 6 (Nov & Dec 2023)

J Research Health 2023, 13(6): 407-416 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Darabi F, Momeni Shabani S, Mardi A, Nejhaddadgar N. Practical Steps in Designing Intervention to Increase Childbearing Desires: An Intervention Mapping Approach. J Research Health 2023; 13 (6) :407-416

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2290-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2290-en.html

1- Department of Public Health, Asadabad School of Medical Sciences, Asadabad, Iran.

2- Psychological Counseling and Leadership Group, Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Turkey.

3- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

4- Department of Health Promotion and Education, School of Public Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran. ,naziladadgar60@gmail.com

2- Psychological Counseling and Leadership Group, Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Turkey.

3- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

4- Department of Health Promotion and Education, School of Public Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 776 kb]

(726 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3070 Views)

Step 1: Needs assessment

IMA systematically integrates theory, literature, and data from a target population to promote structured planning. Following a 6-step progression in the first step, we completed a needs assessment, and the information required for the study was collected in several stages the first phase was with a literature review, focus group, and in-depth semi-structured interviews (data from a target population). Three focus groups consisting of beneficiaries and influential people were formed. In the focus group (n=10 to 15 participants), the topic mentioned by the researcher was discussed for 1 h without any direct suggestions from the researcher. At the end, the opinions of the participants were summarized. In addition, in-depth semi-structured interviews were then conducted with 10 parents, 5 healthcare workers, and 15 neighborhood health volunteers (people’s representatives) to explain their opinions on barriers and strategies to reduce them.

In terms of barriers and solutions to reduce the factors, facilitators, influential elements, and supportive policy changes, the average interview time was 13-40 min. The Interviews were conducted by researchers and trained experts in local health centers and the data collection process in each group (parents, healthcare workers, and neighborhood health volunteers) continued until saturation was reached. Next, the literature was reviewed to identify determinants and strategies for successful interventions to increase parents’ childbearing desires. In the second stage, the current situation of 1288 eligible women (married women in the age range of 15 to 54 years without children, one child, or two children) was investigated and additional data was provided by researcher-made questionnaires based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model, including demographic variables, questions about predisposing factors (awareness, attitude, understanding of risk, and self-efficacy), enabling factors (access to experts for advice), reinforcing factors (encouragement), and policies and regulations (support organizational and environmental factors) [7]. This component focuses on individual (predisposing), interpersonal (enabling), and structural/policy (reinforcing) factors inherent in health behaviors and interventions [7]. The questionnaire was completed for 1288 people.

Step 2: Developing program objectives

In Step 2, we developed program objectives and identified our target population for intervention design. We set our goals based on the results of the needs assessment conducted in the first phase. A matrix of change objectives was developed in this step based on the results previous stage, according to the most important factors. The most important factors that determine parents’ childbearing desires were first selected by reviewing the literature and the expert panel. Childbearing behavior was then divided into performance objectives. Finally, change objectives were written for each of the identified determinants and the determinants and performance objectives were integrated into the matrix of change objectives.

Step 3: Selecting theory-based methods applications

This step required us to choose the theory-based methods and the generation of program ideas in the planning group. Theoretical methods and practical applications were defined following the objectives of the change created in the second step. The methods and program were chosen based on the target population and its culture. The findings of reviewing the literature with the same population were analyzed and practical applications were selected for each method. Furthermore, a brainstorming session was held with the parents to examine their views. They were asked to give feedback on the plans prepared by the planning group and provide ideas to cover the change objectives.

Step 4: Designing the intervention

In this step, an intervention was designed by 5 researchers and experts in health education and promotion with all the components and materials needed for practical application. To implement the practical applications and program materials, a pre-test was predicted, and the coverage of change objectives by educational materials and the compatibility of strategies with theoretical methods were checked by experts.

Step 5 and 6: Developing an implementation plan and evaluation

The intervention program was designed in 10 neighborhoods of Ardabil City, Iran. The interventions were developed at the individual, family (interpersonal), and social levels. The logos were initially designed and the slogan “loneliness is not our right and our children’s” was proposed for the intervention programs. At the individual level, the intervention included training based on the data collected from parents eligible to have children, motivational messages, distribution of posters and booklets, and playing motion graphics in cyberspace groups and newsletters. At the family (interpersonal) level, the intervention included providing a platform for the formation of peer groups concerning the role of family and peers (the literature review in the first step suggested that family and peers have a significant contribution to parents’ childbearing desires). Moreover, at the social level, the intervention included holding local festivals with the participation of parents, drawing competitions for children, cultural-educational camps, and collective programs. The neighborhood liaisons who were selected for each group were asked to brainstorm with parents twice a week in the form of peer groups, report the report of each meeting to the research team, and remove any barriers in the implementation of the programs to evaluate the progress process.

3. Results

Step 1: Needs assessment

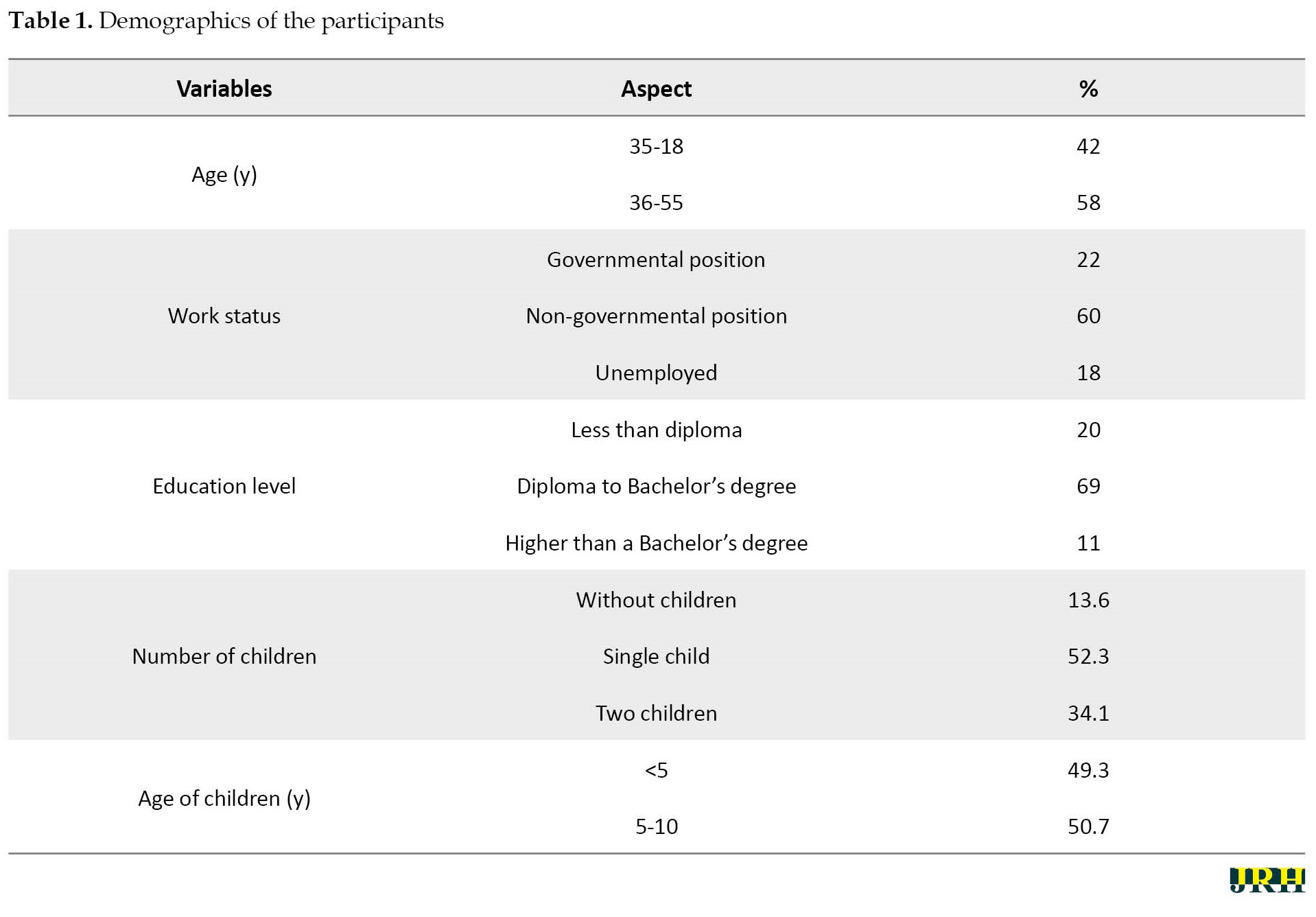

According to the results, the study population considered that factors affecting parents’ childbearing desires were concerned about the future of their children, economic problems, low parenting skills, low self-efficacy, lack of trust in the health system and incentives, the prevalence of low birth rates, mother’s education and employment, the conflict between couples, low social support of couples, lack of access to facilities, fear of pregnancy and childbirth, and medical prohibition. They also observed improving parenting skills, improving skills to interact with the spouse, reducing unemployment and income barriers, increasing social support, providing access to the same facilities, implementing incentive laws, trusting the government’s commitments, using new methods of persuasion, reducing the culture of luxury, and increasing self-efficacy as childbearing solutions and facilitators. According to the results of the literature review, some factors that determine parents’ childbearing desires were concerns about the future of their children [13], economic problems [14], fear of pregnancy [12], lack of housing and jobs [14], parenting skills [15], mother’s education and employment [13], spouse’s unwillingness [16], conflict with the spouse [14], lack of emotional and sexual satisfaction [17], medical prohibition [18] and loss of body beauty [19]. The results demonstrated that the most effective factors in the parents’ childbearing low desires were concerned about the future of their children, economic problems, low parenting skills, and low skills to interact with the spouse. In addition, access to facilities and social support from relatives and family were the next most frequently mentioned factors (Table 1).

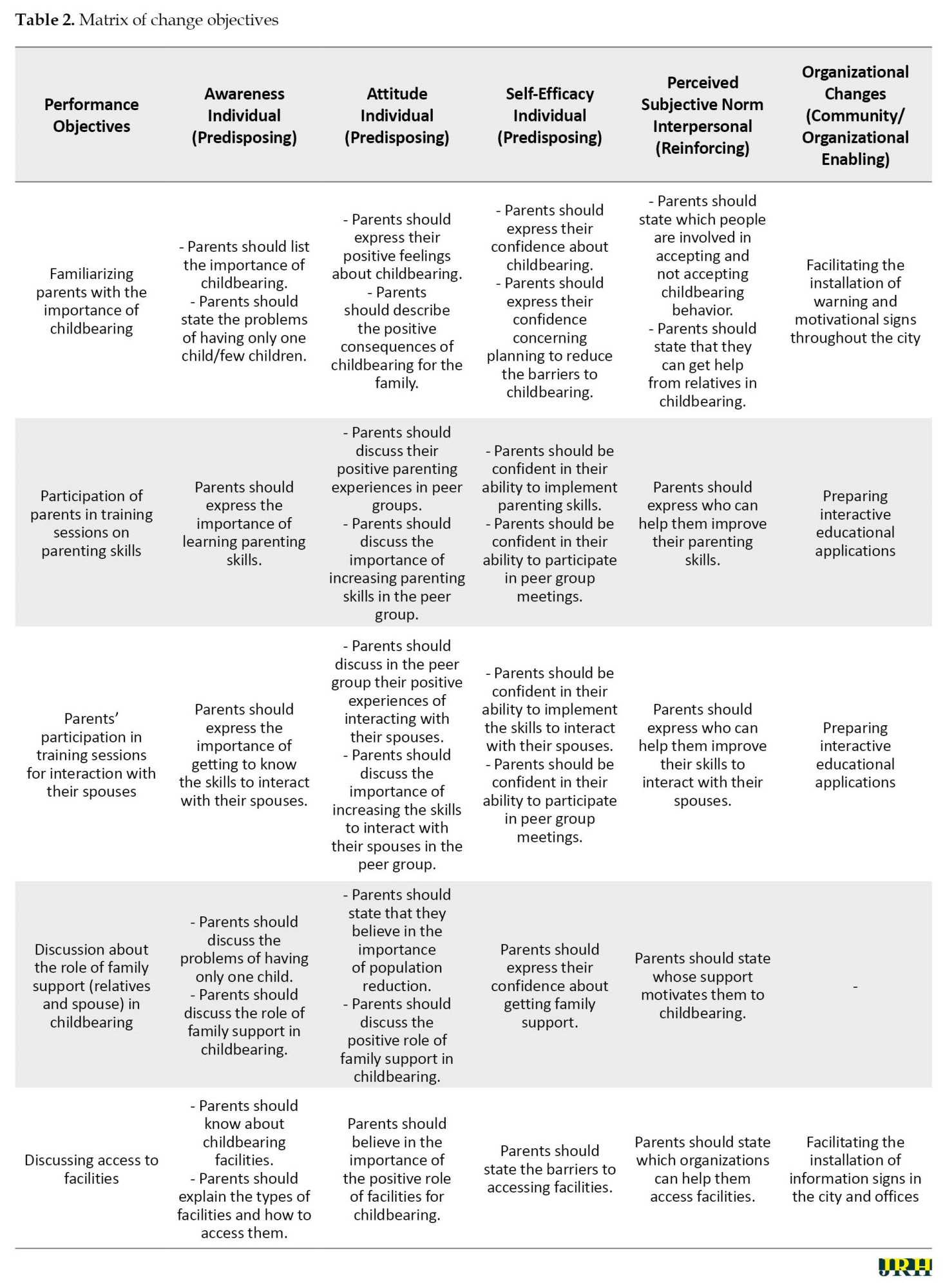

Step 2: Developing program objectives

In the second step, performance objectives, based on theories, were predicted according to program outcomes. The opinions of behavioral specialists, psychologists, midwives, gynecologists, and health education and promotion specialists were then used to revise the performance objectives for validation. In the following, the most important and variable determinants identified in the needs assessment were selected using the focus group method. Finally, awareness, attitude, and self-efficacy were selected as determinants at the individual level, perceived subjective norm at the family level, and organizational changes at the social level based on the results of the needs assessment. The matrix of the objectives was then developed (Table 2).

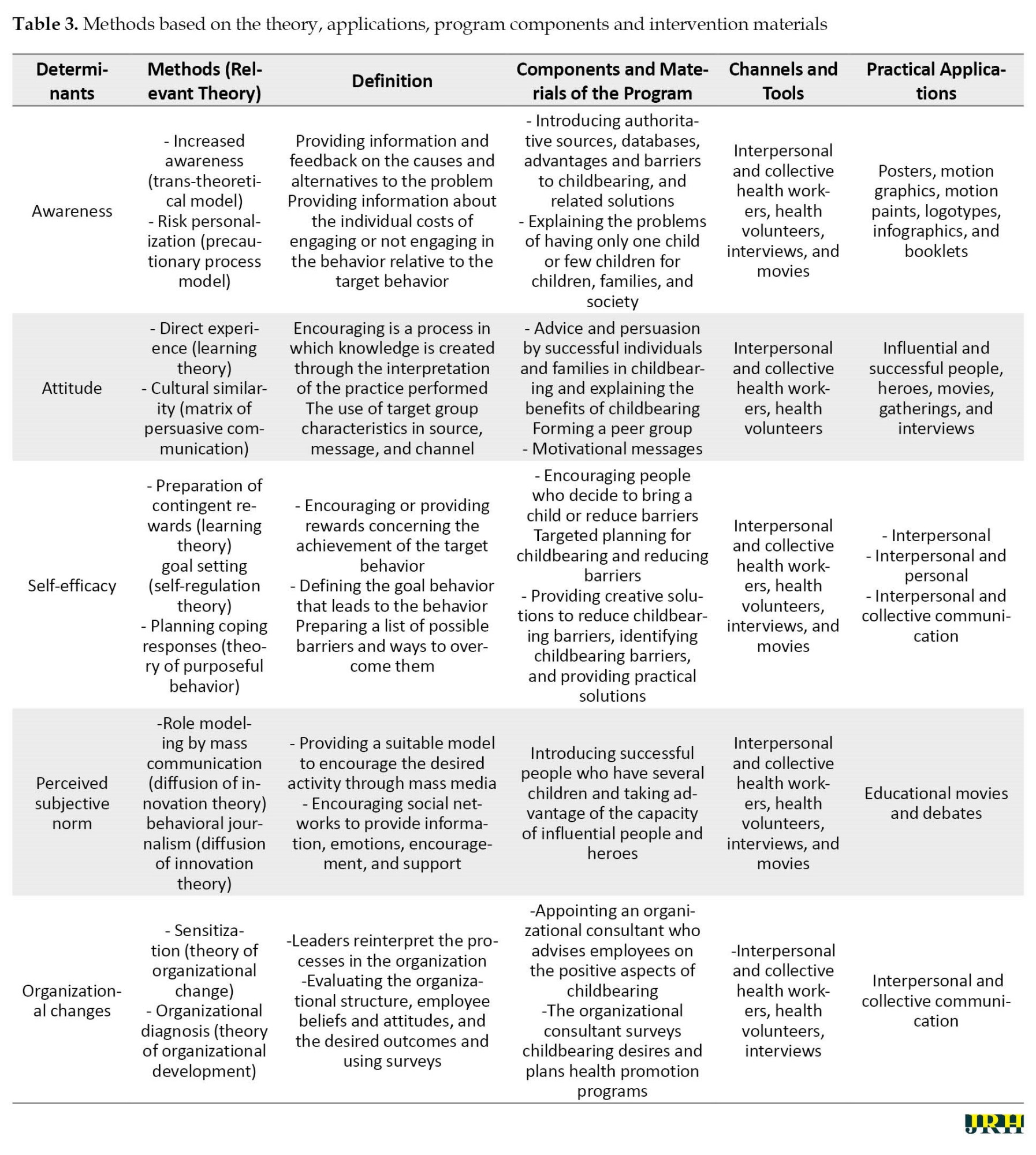

Step 3: Selecting the theory-based methods applications

In the third step, the objectives were identified. We categorized the barriers and divided them into different components of the PRECEDE model. The parents’ childbearing desires were combined with the most frequent and variable determinants obtained in the previous steps. Behavior change methods and practical applications are explained in Table 3.

Step 4: Designing the intervention

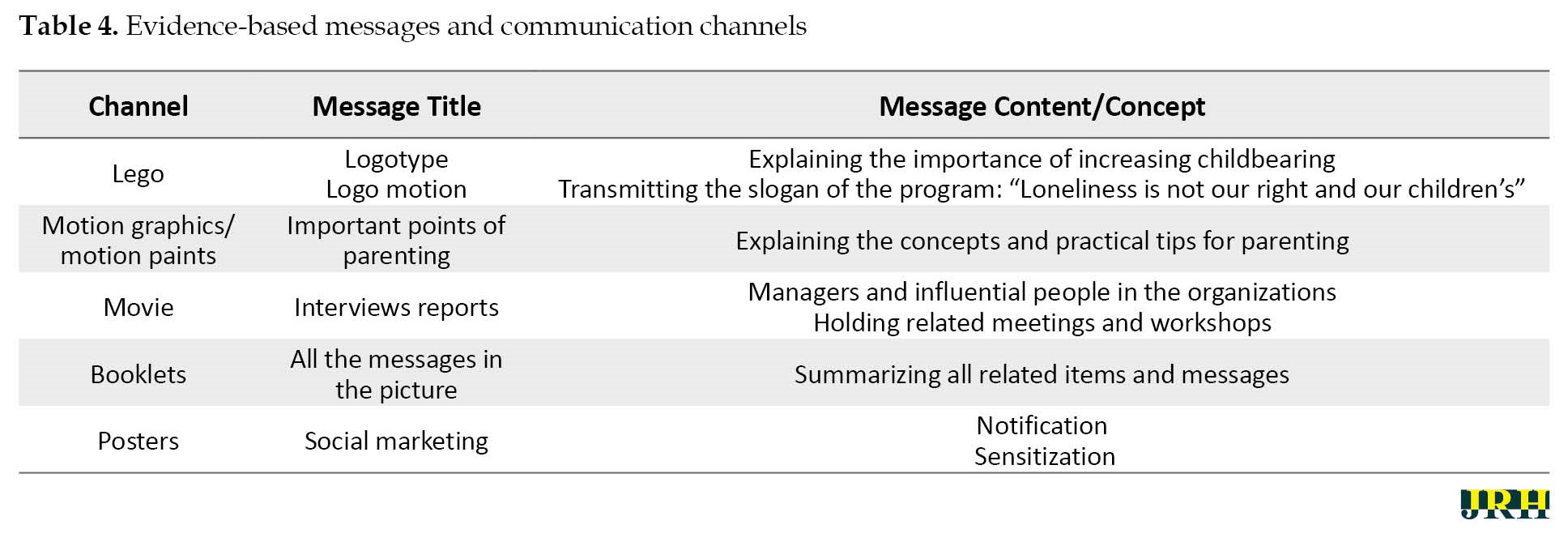

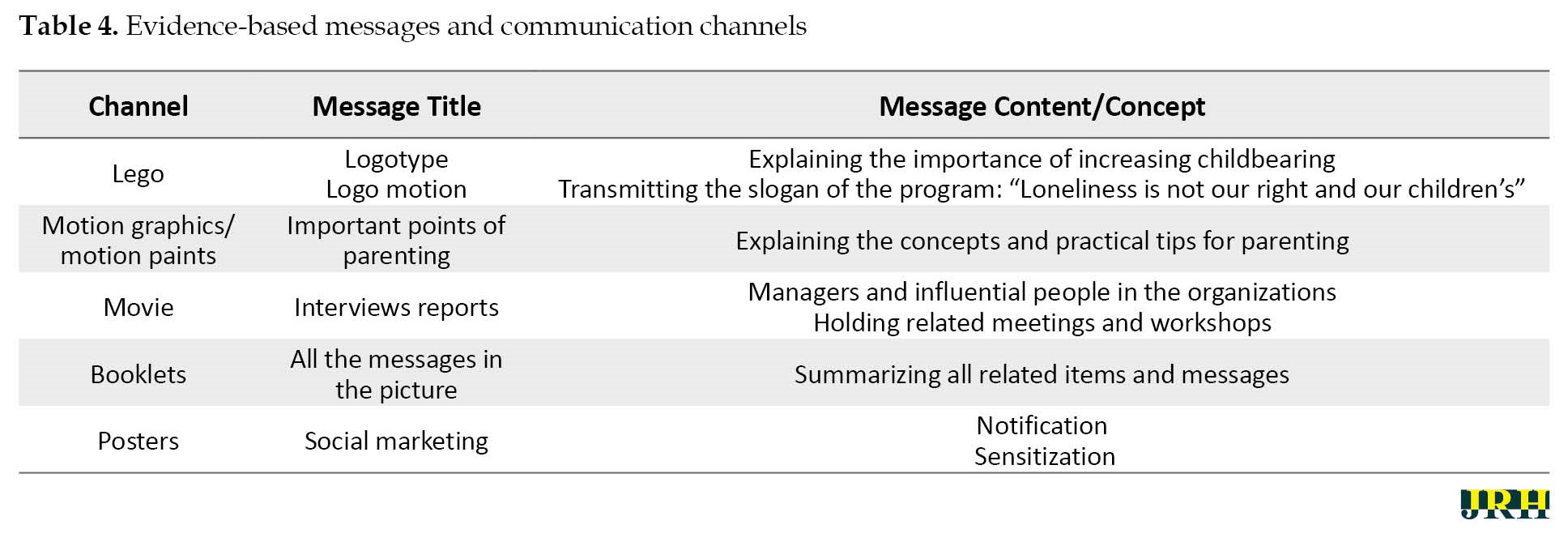

In the fourth step, after identifying the assets, the planning team examined how the resources could address our program objectives, adjusting current assets, and discussed the use of new methods in intervention design. The program components were designed and produced. The scope of the intervention and the most suitable channels for its implementation were provided by the research team. We chose to train final semester students of health education, psychology, and sociology of health to guide eligible parents in the program, answer questions, and if needed, refer to a specialized level to obtain more information. The use of students in this role followed 2 goals: 1) Taking advantage of the capacity of young and energetic forces to establish effective communication and needs assessment, and 2) Empowering the forces to work after graduation, and being able to plan effectively in the social context and identifying the needs of the audience, which is the main goal of targeted programs Table 4.

Step 5 and 6: Developing an implementation plan and evaluation

In this step, executive meetings were held with the members of the research team to design and plan executive actions. A meeting was then held with the participation of the beneficiaries of the program to introduce the beginning of the intervention along with their role in improving and facilitating the implementation process (the adopters of the program, health managers, and program implementers were a combination of consultants and experts, some members of the planning team, and neighborhood liaisons). Meetings were held with the employees of the units after forming executive teams and providing them with adequate training. The effect was evaluated based on the determined general and specific objectives in addition to using the tools completed in the needs assessment stage. The overall objective of the program was to increase parents’ childbearing desires by 15%. The specific objectives were a relative increase in the number of parents participating in peer group programs, a relative increase in the number of educational contents, providing parents with persuasive information, and a relative increase in the number of parents using relevant programs and software. The final evaluation of the program was delayed due to time constraints. The results will be published in other studies.

4. Discussion

One of the approaches that ensure the transparency of all intervention components is IMA, which is a useful technique for developing behavior change interventions and turning theories into practice. The results of the study led to the development of an intervention program to increase parents’ childbearing desires based on the theory and evidence. Health planners and policymakers can choose appropriate behavior change strategies by identifying the determinants of behavior. IMA has been successfully used in studies for planning, intervention, and evaluation [11-13]. In Saudi Arabia, this model was used for early detection and prevention of oral cancer [20]. In South Africa, Aventin [21] used this model for the adaptation of a gender-transformative sexual and reproductive health intervention for adolescent boys. In Iran, Ziapour [10] and Nejhaddadgar [11] used this model to draw a map of intervention in the issue of COVID-19.

5. Conclusion

IMA was successfully used to draw a roadmap for educational interventions to increase the desire to have children. This study has provided a good understanding of the role of intervention mapping in the design of educational interventions to increase the desire to have children, and it is a good basis for effective interventions can be implemented and guided accordingly.

Study strengths and limitations

The limitation of the design of this intervention program is implementation in one province of the country which may limit the generalizability. Regardless of these limitations, the successful use of IMA in intervention design and having a strong coalition of stakeholders and experts provided the first essential steps toward the development of a targeted national program that could replace conventional programs as program implementation. Without the need for assessment and recognition of the influencing factors, it will be ineffective in most cases. Our future research programs include evaluating the effectiveness of this intervention model. Then, using the results of that study and the lessons learned during the intervention development process, we can conduct a larger-scale intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.ARUMS.REC.1401.263).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the educational and research Vice-Chancellor of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences for the financial support and the participants in the various steps of development, implementation, and evaluation of the study.

References

Full-Text: (962 Views)

1. Introduction

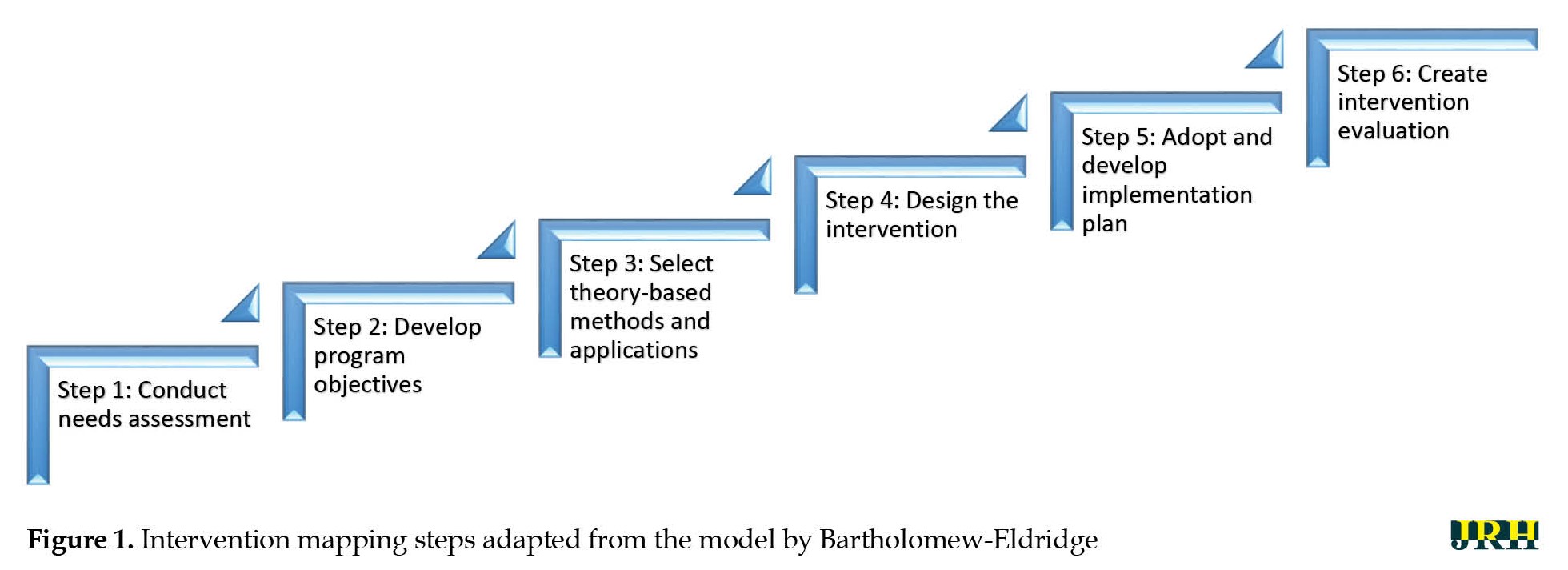

The population and its dimensions are the focal points of any social system. Almost all aspects of human life and the surrounding world are affected by population changes that have many consequences for social, economic, political, and environmental subsystems. Most countries experience reluctance to have children, thereby resulting in declining fertility [1]. The total fertility rate in Iran has decreased to 1.71 children per woman since the previous year. In 2020, the fertility rate dropped to its lowest in recent years. The total fertility rate is the average number of children that a woman can hypothetically have during the childbearing age (15 to 44 years) [2]. There is a concern that fertility will decrease to 0.8 and lead Iran to experience negative growth until 2025 to 2030 [3, 4]. According to research, the population will age but the economic dependency index will increase and governments will be heavily involved in various problems, such as the supply of active labor, the crisis of pension organizations, and the healthcare system if the total fertility rate falls significantly below the replacement level [5]. This requires targeted intervention in different dimensions, including education and cultural development, according to the needs of the society [4, 5]. Classical educational programs common in healthcare systems do not have the desired effects on parents [6, 7]. According to some experts, neglecting the cognitive cause studies and pursuing them without considering the need-based models as a specific conceptual framework in educational planning are among the reasons for the failure of educational programs [7]. Theories and models contribute significantly to the understanding of behavior change mechanisms; therefore, researchers should consider that the use of theory is necessary for a context and the selection and effective use of theories to design, evaluate, and report interventions by combining structures and methods will increase the effectiveness of interventions [8, 9]. Several studies have used this model. The results of Ziapour [10] and Nejhaddadgar [11] have shown that using a targeted approach based on the needs of the audience is effective in changing attitudes and forming behavior. This approach provides a framework to identify behavioral determinants based on the theory and environmental causes of a specific health problem along with guidance to choose the most appropriate methods and applications to address the identified determinants in achieving the alterations in related behavioral and environmental consequences concerning health problems [11]. An intervention mapping approach (IMA) is an iterative process comprising the following six steps: 1) Assessment; 2) identification of outcomes and change objectives; 3) Selection of theory-based intervention methods and practical applications; 4) Development of the intervention program; 5) Implementation; 6) Evaluation [12]. Since the desire to have children is an issue with multiple reasons, without knowing the reasons and the audience, intervention planning will be ineffective. On the other hand, most of the studies that have been conducted have not paid attention to this issue. The present study aims to examine this approach and its steps to design interventions to increase parents’ childbearing desires for the first time. Effective interventions can be developed and implemented on a large scale if used correctly.

2. Methods

In this study, 1288 parents eligible to have children participated in IMA from July to November 2022, aiming to design the practical steps of the intervention to increase childbearing desires. The city was first divided into 5 regions: North, South, East, West, and Central. Then, they randomly selected several clusters (districts) proportional to the population of each region. The sample size was determined based on the inclusion criteria along with a 95% confidence level and 80% test power. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Married women in the age range of 15 to 54 without children; having 1 or 2 children; residency in Ardebil City, Iran; willing to participate in the study. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were having below 15 or over 54 years of age and unwillingness to participate in the study. Before designing the process, a participatory planning group (health department officials, representatives of the population and family group, health volunteers in the neighborhoods, and population and childbearing officials and planners centered on people’s representatives and health education experts) was formed to ensure the participation of beneficiaries and influential people. In addition, the views of the beneficiaries, influential people, and people’s representatives were considered in all steps of IMA (Figure 1).

The population and its dimensions are the focal points of any social system. Almost all aspects of human life and the surrounding world are affected by population changes that have many consequences for social, economic, political, and environmental subsystems. Most countries experience reluctance to have children, thereby resulting in declining fertility [1]. The total fertility rate in Iran has decreased to 1.71 children per woman since the previous year. In 2020, the fertility rate dropped to its lowest in recent years. The total fertility rate is the average number of children that a woman can hypothetically have during the childbearing age (15 to 44 years) [2]. There is a concern that fertility will decrease to 0.8 and lead Iran to experience negative growth until 2025 to 2030 [3, 4]. According to research, the population will age but the economic dependency index will increase and governments will be heavily involved in various problems, such as the supply of active labor, the crisis of pension organizations, and the healthcare system if the total fertility rate falls significantly below the replacement level [5]. This requires targeted intervention in different dimensions, including education and cultural development, according to the needs of the society [4, 5]. Classical educational programs common in healthcare systems do not have the desired effects on parents [6, 7]. According to some experts, neglecting the cognitive cause studies and pursuing them without considering the need-based models as a specific conceptual framework in educational planning are among the reasons for the failure of educational programs [7]. Theories and models contribute significantly to the understanding of behavior change mechanisms; therefore, researchers should consider that the use of theory is necessary for a context and the selection and effective use of theories to design, evaluate, and report interventions by combining structures and methods will increase the effectiveness of interventions [8, 9]. Several studies have used this model. The results of Ziapour [10] and Nejhaddadgar [11] have shown that using a targeted approach based on the needs of the audience is effective in changing attitudes and forming behavior. This approach provides a framework to identify behavioral determinants based on the theory and environmental causes of a specific health problem along with guidance to choose the most appropriate methods and applications to address the identified determinants in achieving the alterations in related behavioral and environmental consequences concerning health problems [11]. An intervention mapping approach (IMA) is an iterative process comprising the following six steps: 1) Assessment; 2) identification of outcomes and change objectives; 3) Selection of theory-based intervention methods and practical applications; 4) Development of the intervention program; 5) Implementation; 6) Evaluation [12]. Since the desire to have children is an issue with multiple reasons, without knowing the reasons and the audience, intervention planning will be ineffective. On the other hand, most of the studies that have been conducted have not paid attention to this issue. The present study aims to examine this approach and its steps to design interventions to increase parents’ childbearing desires for the first time. Effective interventions can be developed and implemented on a large scale if used correctly.

2. Methods

In this study, 1288 parents eligible to have children participated in IMA from July to November 2022, aiming to design the practical steps of the intervention to increase childbearing desires. The city was first divided into 5 regions: North, South, East, West, and Central. Then, they randomly selected several clusters (districts) proportional to the population of each region. The sample size was determined based on the inclusion criteria along with a 95% confidence level and 80% test power. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Married women in the age range of 15 to 54 without children; having 1 or 2 children; residency in Ardebil City, Iran; willing to participate in the study. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were having below 15 or over 54 years of age and unwillingness to participate in the study. Before designing the process, a participatory planning group (health department officials, representatives of the population and family group, health volunteers in the neighborhoods, and population and childbearing officials and planners centered on people’s representatives and health education experts) was formed to ensure the participation of beneficiaries and influential people. In addition, the views of the beneficiaries, influential people, and people’s representatives were considered in all steps of IMA (Figure 1).

Step 1: Needs assessment

IMA systematically integrates theory, literature, and data from a target population to promote structured planning. Following a 6-step progression in the first step, we completed a needs assessment, and the information required for the study was collected in several stages the first phase was with a literature review, focus group, and in-depth semi-structured interviews (data from a target population). Three focus groups consisting of beneficiaries and influential people were formed. In the focus group (n=10 to 15 participants), the topic mentioned by the researcher was discussed for 1 h without any direct suggestions from the researcher. At the end, the opinions of the participants were summarized. In addition, in-depth semi-structured interviews were then conducted with 10 parents, 5 healthcare workers, and 15 neighborhood health volunteers (people’s representatives) to explain their opinions on barriers and strategies to reduce them.

In terms of barriers and solutions to reduce the factors, facilitators, influential elements, and supportive policy changes, the average interview time was 13-40 min. The Interviews were conducted by researchers and trained experts in local health centers and the data collection process in each group (parents, healthcare workers, and neighborhood health volunteers) continued until saturation was reached. Next, the literature was reviewed to identify determinants and strategies for successful interventions to increase parents’ childbearing desires. In the second stage, the current situation of 1288 eligible women (married women in the age range of 15 to 54 years without children, one child, or two children) was investigated and additional data was provided by researcher-made questionnaires based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model, including demographic variables, questions about predisposing factors (awareness, attitude, understanding of risk, and self-efficacy), enabling factors (access to experts for advice), reinforcing factors (encouragement), and policies and regulations (support organizational and environmental factors) [7]. This component focuses on individual (predisposing), interpersonal (enabling), and structural/policy (reinforcing) factors inherent in health behaviors and interventions [7]. The questionnaire was completed for 1288 people.

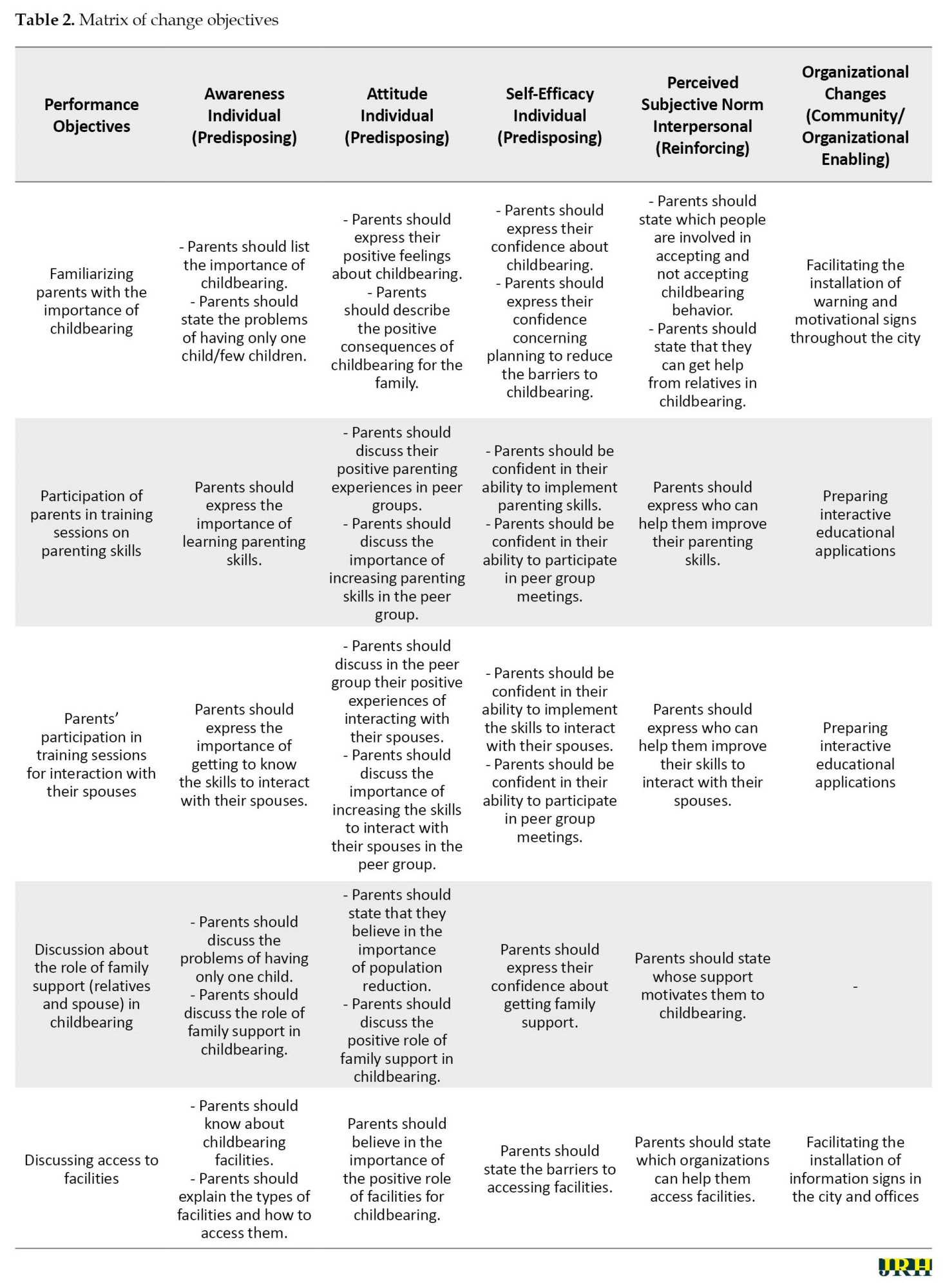

Step 2: Developing program objectives

In Step 2, we developed program objectives and identified our target population for intervention design. We set our goals based on the results of the needs assessment conducted in the first phase. A matrix of change objectives was developed in this step based on the results previous stage, according to the most important factors. The most important factors that determine parents’ childbearing desires were first selected by reviewing the literature and the expert panel. Childbearing behavior was then divided into performance objectives. Finally, change objectives were written for each of the identified determinants and the determinants and performance objectives were integrated into the matrix of change objectives.

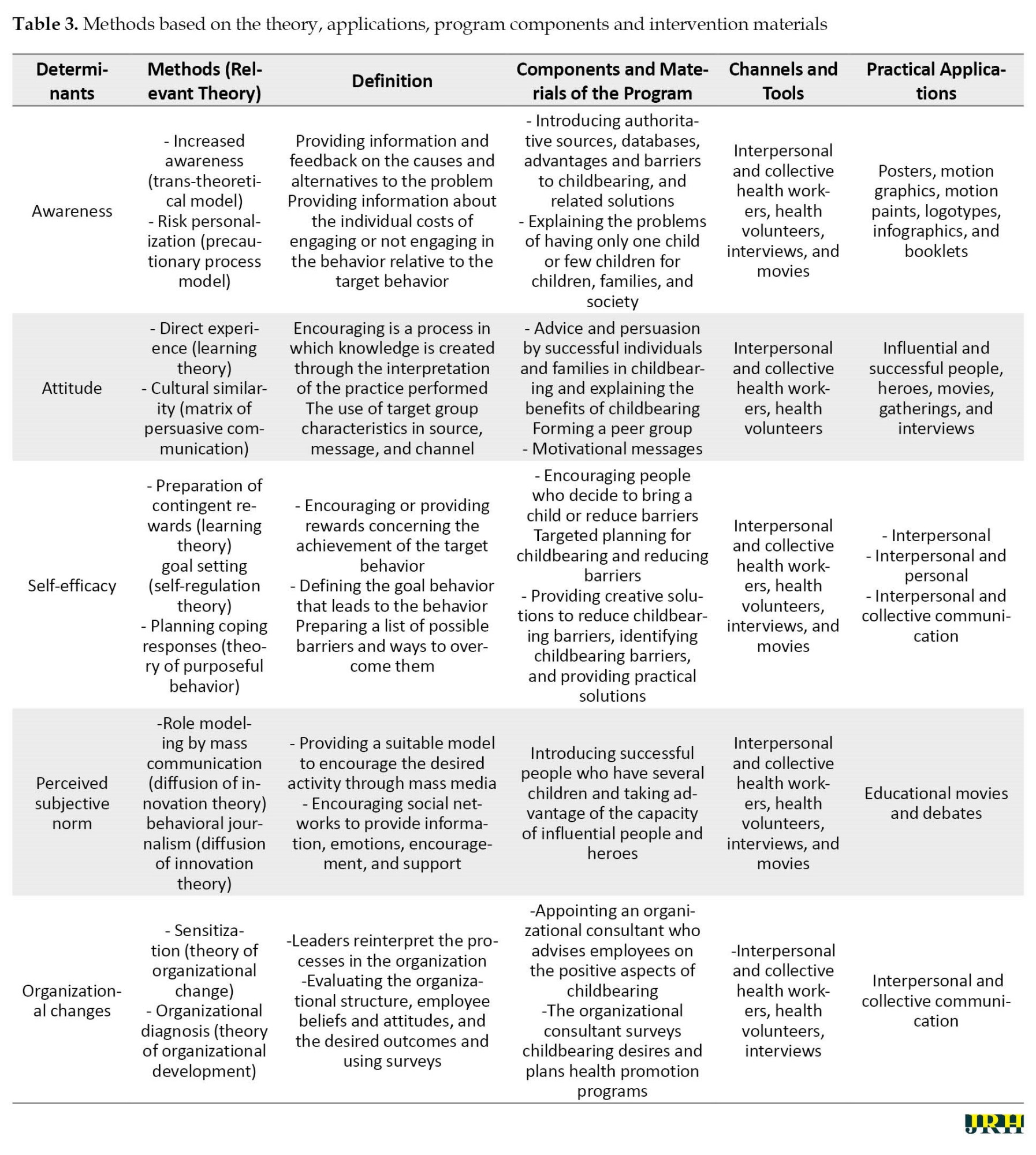

Step 3: Selecting theory-based methods applications

This step required us to choose the theory-based methods and the generation of program ideas in the planning group. Theoretical methods and practical applications were defined following the objectives of the change created in the second step. The methods and program were chosen based on the target population and its culture. The findings of reviewing the literature with the same population were analyzed and practical applications were selected for each method. Furthermore, a brainstorming session was held with the parents to examine their views. They were asked to give feedback on the plans prepared by the planning group and provide ideas to cover the change objectives.

Step 4: Designing the intervention

In this step, an intervention was designed by 5 researchers and experts in health education and promotion with all the components and materials needed for practical application. To implement the practical applications and program materials, a pre-test was predicted, and the coverage of change objectives by educational materials and the compatibility of strategies with theoretical methods were checked by experts.

Step 5 and 6: Developing an implementation plan and evaluation

The intervention program was designed in 10 neighborhoods of Ardabil City, Iran. The interventions were developed at the individual, family (interpersonal), and social levels. The logos were initially designed and the slogan “loneliness is not our right and our children’s” was proposed for the intervention programs. At the individual level, the intervention included training based on the data collected from parents eligible to have children, motivational messages, distribution of posters and booklets, and playing motion graphics in cyberspace groups and newsletters. At the family (interpersonal) level, the intervention included providing a platform for the formation of peer groups concerning the role of family and peers (the literature review in the first step suggested that family and peers have a significant contribution to parents’ childbearing desires). Moreover, at the social level, the intervention included holding local festivals with the participation of parents, drawing competitions for children, cultural-educational camps, and collective programs. The neighborhood liaisons who were selected for each group were asked to brainstorm with parents twice a week in the form of peer groups, report the report of each meeting to the research team, and remove any barriers in the implementation of the programs to evaluate the progress process.

3. Results

Step 1: Needs assessment

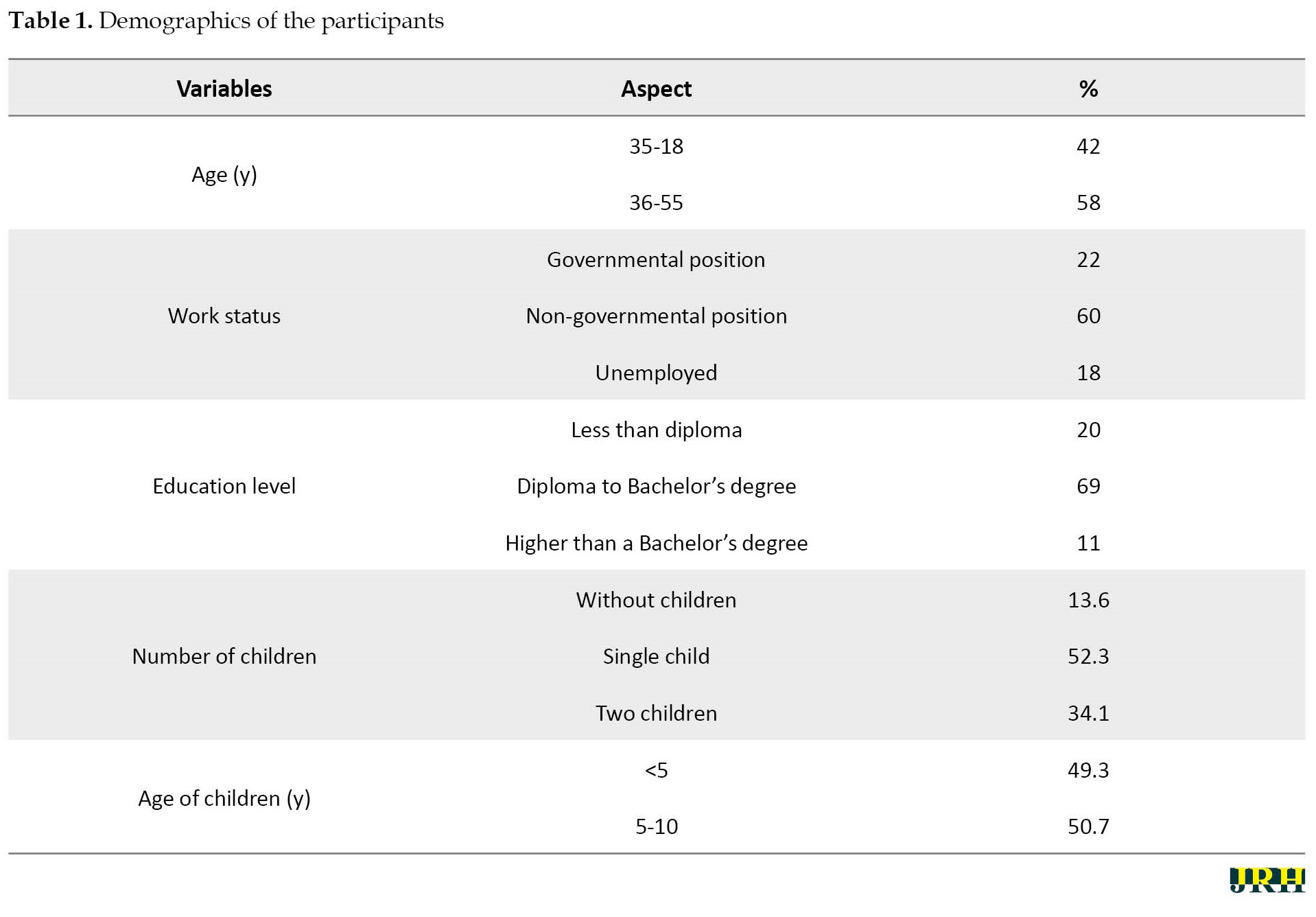

According to the results, the study population considered that factors affecting parents’ childbearing desires were concerned about the future of their children, economic problems, low parenting skills, low self-efficacy, lack of trust in the health system and incentives, the prevalence of low birth rates, mother’s education and employment, the conflict between couples, low social support of couples, lack of access to facilities, fear of pregnancy and childbirth, and medical prohibition. They also observed improving parenting skills, improving skills to interact with the spouse, reducing unemployment and income barriers, increasing social support, providing access to the same facilities, implementing incentive laws, trusting the government’s commitments, using new methods of persuasion, reducing the culture of luxury, and increasing self-efficacy as childbearing solutions and facilitators. According to the results of the literature review, some factors that determine parents’ childbearing desires were concerns about the future of their children [13], economic problems [14], fear of pregnancy [12], lack of housing and jobs [14], parenting skills [15], mother’s education and employment [13], spouse’s unwillingness [16], conflict with the spouse [14], lack of emotional and sexual satisfaction [17], medical prohibition [18] and loss of body beauty [19]. The results demonstrated that the most effective factors in the parents’ childbearing low desires were concerned about the future of their children, economic problems, low parenting skills, and low skills to interact with the spouse. In addition, access to facilities and social support from relatives and family were the next most frequently mentioned factors (Table 1).

Step 2: Developing program objectives

In the second step, performance objectives, based on theories, were predicted according to program outcomes. The opinions of behavioral specialists, psychologists, midwives, gynecologists, and health education and promotion specialists were then used to revise the performance objectives for validation. In the following, the most important and variable determinants identified in the needs assessment were selected using the focus group method. Finally, awareness, attitude, and self-efficacy were selected as determinants at the individual level, perceived subjective norm at the family level, and organizational changes at the social level based on the results of the needs assessment. The matrix of the objectives was then developed (Table 2).

Step 3: Selecting the theory-based methods applications

In the third step, the objectives were identified. We categorized the barriers and divided them into different components of the PRECEDE model. The parents’ childbearing desires were combined with the most frequent and variable determinants obtained in the previous steps. Behavior change methods and practical applications are explained in Table 3.

Step 4: Designing the intervention

In the fourth step, after identifying the assets, the planning team examined how the resources could address our program objectives, adjusting current assets, and discussed the use of new methods in intervention design. The program components were designed and produced. The scope of the intervention and the most suitable channels for its implementation were provided by the research team. We chose to train final semester students of health education, psychology, and sociology of health to guide eligible parents in the program, answer questions, and if needed, refer to a specialized level to obtain more information. The use of students in this role followed 2 goals: 1) Taking advantage of the capacity of young and energetic forces to establish effective communication and needs assessment, and 2) Empowering the forces to work after graduation, and being able to plan effectively in the social context and identifying the needs of the audience, which is the main goal of targeted programs Table 4.

Step 5 and 6: Developing an implementation plan and evaluation

In this step, executive meetings were held with the members of the research team to design and plan executive actions. A meeting was then held with the participation of the beneficiaries of the program to introduce the beginning of the intervention along with their role in improving and facilitating the implementation process (the adopters of the program, health managers, and program implementers were a combination of consultants and experts, some members of the planning team, and neighborhood liaisons). Meetings were held with the employees of the units after forming executive teams and providing them with adequate training. The effect was evaluated based on the determined general and specific objectives in addition to using the tools completed in the needs assessment stage. The overall objective of the program was to increase parents’ childbearing desires by 15%. The specific objectives were a relative increase in the number of parents participating in peer group programs, a relative increase in the number of educational contents, providing parents with persuasive information, and a relative increase in the number of parents using relevant programs and software. The final evaluation of the program was delayed due to time constraints. The results will be published in other studies.

4. Discussion

One of the approaches that ensure the transparency of all intervention components is IMA, which is a useful technique for developing behavior change interventions and turning theories into practice. The results of the study led to the development of an intervention program to increase parents’ childbearing desires based on the theory and evidence. Health planners and policymakers can choose appropriate behavior change strategies by identifying the determinants of behavior. IMA has been successfully used in studies for planning, intervention, and evaluation [11-13]. In Saudi Arabia, this model was used for early detection and prevention of oral cancer [20]. In South Africa, Aventin [21] used this model for the adaptation of a gender-transformative sexual and reproductive health intervention for adolescent boys. In Iran, Ziapour [10] and Nejhaddadgar [11] used this model to draw a map of intervention in the issue of COVID-19.

5. Conclusion

IMA was successfully used to draw a roadmap for educational interventions to increase the desire to have children. This study has provided a good understanding of the role of intervention mapping in the design of educational interventions to increase the desire to have children, and it is a good basis for effective interventions can be implemented and guided accordingly.

Study strengths and limitations

The limitation of the design of this intervention program is implementation in one province of the country which may limit the generalizability. Regardless of these limitations, the successful use of IMA in intervention design and having a strong coalition of stakeholders and experts provided the first essential steps toward the development of a targeted national program that could replace conventional programs as program implementation. Without the need for assessment and recognition of the influencing factors, it will be ineffective in most cases. Our future research programs include evaluating the effectiveness of this intervention model. Then, using the results of that study and the lessons learned during the intervention development process, we can conduct a larger-scale intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.ARUMS.REC.1401.263).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the educational and research Vice-Chancellor of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences for the financial support and the participants in the various steps of development, implementation, and evaluation of the study.

References

- Perez NP, Ahmad H, Alemayehu H, Newman EA, Reyes-Ferral C. The impact of social determinants of health on the overall wellbeing of children: A review for the pediatric surgeon. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2022; 57(4):587-97. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.10.018] [PMID]

- Kordzanganeh J, Mohamadian H. [Psychometric assessment of the validity of the Iranian version of attitude toward fertility and childbearing inventory in women without a history of pregnancy in the South of Iran (Persian)]. Journal of School of Public Health & Institute of Public Health Research. 2019; 17(1):83-94. [Link]

- Arhin SK, Tang R, Hamid A, Dzandu D, Akpetey BK. Knowledge, attitude, and perceptions about in Vitro Fertilization (IVF) among women of childbearing age in Cape Coast, Ghana. Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2022; 2022:5129199. [DOI:10.1155/2022/5129199] [PMID]

- Alimoradi Z, Zarabadipour S, Arrato NA, Griffiths MD, Andersen BL, Bahrami N. The relationship between cognitive schemas activated in sexual context and early maladaptive schemas among married women of childbearing age. BMC Psychology. 2022; 10(1):131. [DOI:10.1186/s40359-022-00829-1] [PMID]

- Speizer IS, Calhoun LM. Her, his, and their fertility desires and contraceptive behaviours: A focus on young couples in six countries. Global Public Health. 2022; 17(7):1282-98. [DOI:10.1080/17441692.2021.1922732] [PMID]

- Corona LE, Hirsch J, Rosoklija I, Yerkes EB, Johnson EK. Attitudes toward fertility-related care and education of adolescents and young adults with differences of sex development: Informing future care models. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2022; 18(4):491.e1-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.05.009] [PMID]

- Azar FE, Solhi M, Darabi F, Rohban A, Abolfathi M, Nejhaddadgar N. Effect of educational intervention based on PRECEDE-PROCEED model combined with self-management theory on self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. 2018; 12(6):1075-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.dsx.2018.06.028] [PMID]

- Darabi F, Kaveh MH, Khalajabadi Farahani F, Yaseri M, Majlessi F, Shojaeizadeh D. The effect of a theory of planned behavior-based educational intervention on sexual and reproductive health in Iranian adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2017; 17(4):400. [PMCID]

- Darabi F, Yaseri M. Intervention to Improve Menstrual Health Among Adolescent Girls Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior in Iran: A Cluster-randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2022; 55(6):595-603. [DOI:10.3961/jpmph.22.365] [PMID]

- Ziapour A, Sharma M, NeJhaddadgar N, Mardi A, Tavafian SS. Study of adolescents’ puberty, adolescence training program: The application of intervention mapping approach. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2021; 42(1):5-14. [DOI:10.1177/0272684X20956485] [PMID]

- Nejhaddadgar N, Azadi H, Mehedi N, Toghroli R, Faraji A. Teaching adults how to prevent COVID-19 infection by health workers: The application of intervention mapping approach. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2021; 10:24. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1398_20] [PMID]

- Weil MT, Spinler K, Lieske B, Dingoyan D, Walther C, Heydecke G, et al. An evidence-based digital prevention program to improve oral health literacy of people with a migration background: Intervention mapping approach. JMIR Form Res. 2023; 7:e36815. [DOI:10.2196/36815] [PMID]

- Fang Y, Boelens M, Windhorst DA, Raat H, van Grieken A. Factors associated with parenting self-efficacy: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2021; 77(6):2641-61. [DOI:10.1111/jan.14767] [PMID]

- Pedro J, Brandão T, Schmidt L, Costa ME, Martins MV. What do people know about fertility? A systematic review on fertility awareness and its associated factors. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018; 123(2):71-81. [DOI:10.1080/03009734.2018.1480186] [PMID]

- Sekine K, Khadka N, Carandang RR, Ong KIC, Tamang A, Jimba M. Multilevel factors influencing contraceptive use and childbearing among adolescent girls in Bara district of Nepal: A qualitative study using the socioecological model. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(10):e046156. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046156] [PMID]

- Henry EG, Lehnertz NB, Alam A, Ali NA, Williams EK, Rahman SM, et al. Sociocultural factors perpetuating the practices of early marriage and childbirth in Sylhet District, Bangladesh. International Health. 2015; 7(3):212-7. [DOI:10.1093/inthealth/ihu074] [PMID]

- Abdulai M, Kenu E, Ameme DK, Bandoh DA, Tabong PT, Lartey AA, et al. Demographic and socio-cultural factors influencing contraceptive uptake among women of reproductive age in Tamale Metropolis, Northern Region, Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2020; 54(2 Suppl):64-72. [DOI:10.4314/gmj.v54i2s.11] [PMID]

- Wells JCK, Marphatia AA, Cortina-Borja M, Manandhar DS, Reid AM, Saville N. Maternal physical, socioeconomic, and demographic characteristics and childbirth complications in rural lowland Nepal: Applying an evolutionary framework to understand the role of phenotypic plasticity. American Journal of Human Biology. 2021; 33(6):e23566. [DOI:10.1002/ajhb.23566] [PMID]

- Kramer KL, Hackman J, Schacht R, Davis HE. Effects of family planning on fertility behaviour across the demographic transition. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1):8835. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-86180-8] [PMID]

- Jafer M, Moafa I, Crutzen R, van den Borne B. Using intervention mapping to develop ISAC, a comprehensive intervention for early detection and prevention of oral cancer in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Cancer Education. 2023; 38(2):505-12. [DOI:10.1007/s13187-022-02146-y] [PMID]

- Aventin Á, Rabie S, Skeen S, Tomlinson M, Makhetha M, Siqabatiso Z, et al. Adaptation of a gender-transformative sexual and reproductive health intervention for adolescent boys in South Africa and Lesotho using intervention mapping. Global Health Action. 2021; 14(1):1927329. [DOI:10.1080/16549716.2021.1927329] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Health Systems

Received: 2023/02/26 | Accepted: 2023/05/13 | Published: 2023/10/3

Received: 2023/02/26 | Accepted: 2023/05/13 | Published: 2023/10/3

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |