Volume 13, Issue 6 (Nov & Dec 2023)

J Research Health 2023, 13(6): 437-446 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nejad Rodani R S, Marashian F S, Shahbazi M. Relative Effectiveness of Acceptance/Commitment and Schema Therapies on Love Trauma Syndrome and Self-compassion in Unmarried Girls With Emotional Breakdown. J Research Health 2023; 13 (6) :437-446

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2301-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2301-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,fsadatmarashian@gmail.com

3- Department of Counseling, Masjed Soleiman Branch, Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

3- Department of Counseling, Masjed Soleiman Branch, Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 599 kb]

(1490 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3741 Views)

Full-Text: (1597 Views)

1. Introduction

Establishing a stable, meaningful relationship is considered a critical social human capacity. Parent–infant bonds, child–parent bonds, infatuations in adolescence and youth, close friendships, and other human connections are essential for physical and mental health [1]. During childhood, relationships with parents are often described as the most important type of relationship [2, 3]. However, relationships with love partners gradually gain importance in adolescence and youth. Failure to establish and maintain close romantic relationships with commitment can hinder an individual’s development and adversely affect their well-being in life due to the potential emergence of serious problems [4]. In their romantic relationships, people experience higher levels of intimacy toward their partners than others. As a result, the stability and quality of these relationships can directly and indirectly affect psychological and physical health during their entire life [5]. Breaking up from a romantic relationship is among the most excruciating events that can occur in a person’s life. It has a substantial role in short-term and long-term adjustments [6]. Psychological disorders will emerge if the basic and emotional needs for establishing and forming high-quality and stable relationships are left unsatisfied [7, 8]. Verhallen et al. [6] reported that symptoms of depression are evident in people who have recent romantic relationship breakups.

Emotional breakdown leads to a very prevalent and deep experience of loss and sorrow. Failing or ending a romantic relationship in adolescence or youth is not unusual. Failure in a relationship has been introduced as a typical source of stress for university students [9]. Upon entering universities, students experience new dimensions of romantic relationships because they develop more specific emotional needs as they encounter a unique situation in which they are away from their families [10]. Moreover, they find opportunities to communicate with the opposite sex. The consequent traumas of romantic relationships have cognitive, emotional, physical, individual, and social dimensions [11]. Ghazinejad et al. [12] reported that girls with symptoms of love trauma syndrome would manifest maladaptive reactions, such as confusion, uncompromising decisions, bargaining, change of beliefs, cognitive distortions, and rumination.

Self-compassion is directly related to positive psychological health and can be defined as a positive self-stance. It is also considered an effective attribute and a protective factor for romantic flexibility [13]. Tiwari et al. [14] reported that self-compassion is a complex process bringing in cognitive, affective, and behavioral resources for the individual. According to research, self-compassion can improve a person’s coping ability to encounter failures [15]. Self-compassion means the feelings of self-care and self-kindness as well as perception and attitude without judgments on personal shortcomings and failures. It also means that personal experiences are included in typical human experiences [16]. Studies have reported that self-compassion strongly correlates with mental health and well-being [17, 18]. Pandey et al. [18] said that self-esteem and self-compassion have predictive strengths for hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Individuals with higher levels of self-compassion experience lower levels of depression, anxiety, rumination, and intellectual suppression than individuals lacking self-compassion. They also experience higher happiness, optimism, life satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, emotional quotient, coping skills, intelligence, and flexibility than those who severely criticize themselves [14, 19]. According to different studies, people with high self-compassion can resolve conflicts in relationships with their love partners through compromising solutions that meet the needs of their partners by establishing a balance [20-22]. Kaya et al. [23] reported that self-compassion significantly predicts both relationship satisfaction and conflict resolution styles in romantic relationships. Therefore, improving self-compassion using cognitive psychotherapy methods and psychological interventions can contribute to solving family conflicts and improving romantic relationships.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a therapeutic method that has been effective in helping adolescents with emotional breakdowns [9]. ACT identifies avoidance of pain and tension as the main problem that leads to inability and reduces life satisfaction [24]. According to ACT, avoidance occurs when negative thoughts and emotions severely affect behavior [25]. Hence, the critical method of ACT is to make patients encounter situations that have already been avoided. ACT changes a patient’s relationships with their thoughts and feelings so that they have no longer considered symptoms [26]. The ultimate goal is to change these painful thoughts and feelings from their previous forms, which are interpreted as harmful symptoms that prevent a meaningful and enriched life, to their new forms, which are interpreted as the natural experiences of humans that are considered part of a meaningful and enriched life [27, 28]. Because of these characteristics (acceptance without avoidance of adverse experiences), ACT can probably help girls with emotional breakdowns stop interpreting experiences as negative events. It can significantly improve their mental health in general. Noormohamadi et al. [9] reported that ACT improved mental health in students with an emotional breakdown. Meanwhile, Mohammadian et al. [26] reported that ACT effectively decreased cognitive avoidance and increased empathy in couples with low marital adjustment.

The presence of early maladaptive schemas can lead to an emotional breakdown [29]. Correlated with negative events in life, these schemas cause cognitive trauma and make people with emotional breakdowns vulnerable to inefficient attitudes, distress, and psychological disorders [30, 31]. Schema therapy is a novel, integrated approach mainly based on expanding classic cognitive-behavioral therapy methods and concepts [32]. Moreover, schema therapy has integrated the principles and foundations of cognitive-behavioral methods into attachment, gestalt, object relationships, constructivism, and psychiatry in a valuable conceptual therapy model [33]. Some early maladaptive schemas, such as emotional deprivation or attachment, play critical roles in the emergence of psychological disorders and symptoms of an emotional breakdown after failure in a romantic relationship [34]. Hence, schema therapy can significantly help such individuals by identifying and targeting these maladaptive schemas. Mohammadi et al. [35] reported that schema therapy effectively improved the components of marital conflict and reduced emotional reactions in women.

Emotional failure is introduced as one of the most painful experiences in life. Experiencing emotional failure leads to experiencing many negative emotions, such as anger and depression. If these emotions are not controlled in time, they can lead to more significant problems in life. In this situation, the best thing to do is to use professional psychotherapy services and get help from an experienced specialist. One of the current research innovations is comparing ACT and schema therapy interventions in girls with emotional breakdowns. The results of this study can be effective in choosing an effective method to control negative emotions and improve self-compassion in people with love failure. Accordingly, the present study compares the effectiveness of ACT and schema therapy on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns.

2. Methods

This quasi-experimental research adopted a pre-test-post-test design with a control group and follow-up. The statistical population included all unmarried girls experiencing an emotional breakdown in Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province, Iran, in 2022. The convenience sampling method was employed to select 45 available girls with an emotional breakdown in 2022. We included 15 girls with an emotional breakdown in each group using the G*Power software, version 3.1 with an effect size of 1.25, a test power of 0.95, and α of 0.05. They were then randomly assigned to an ACT, schema therapy, and control group. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Being in the age range of 18 to 30 years, having experienced an emotional breakdown, and being unmarried. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Having any psychological disorders, taking psychiatric drugs, having various short-term romantic relationships, having been married and divorced, and experiencing the death of a spouse.

Study measures

Love trauma inventory

Developed by Rosse [36], the love trauma inventory (LTI) checklist consists of 10 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 to 3). Items 1 and 2 are scored inversely. The scores of this checklist range from 0 to 30, as higher scores indicate more severe love traumas. The cut-off point is 20. The results of Etemadnia et al. [37] indicated the good validity of this questionnaire. Moreover, Etemadnia et al. [37] reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.83 for the Persian version of the questionnaire. In the current study, the Cronbach α for this instrument was obtained at 0.86.

Self-compassion scale–short form

Developed by Raes et al. [38], the self-comparison scale- short form (SCS–SF) includes 12 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1=never to 5=always) the scores on this scale range from 12 to 60. Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-kindness. The results of Shahbazi et al. [39] indicated the good validity of the SCS–SF. The total reliability of the scale was 0.91 using the Cronbach α coefficient, and its validity was significant at 0.001 [39]. The Cronbach α of this scale was 0.87 in the present study.

Study procedure

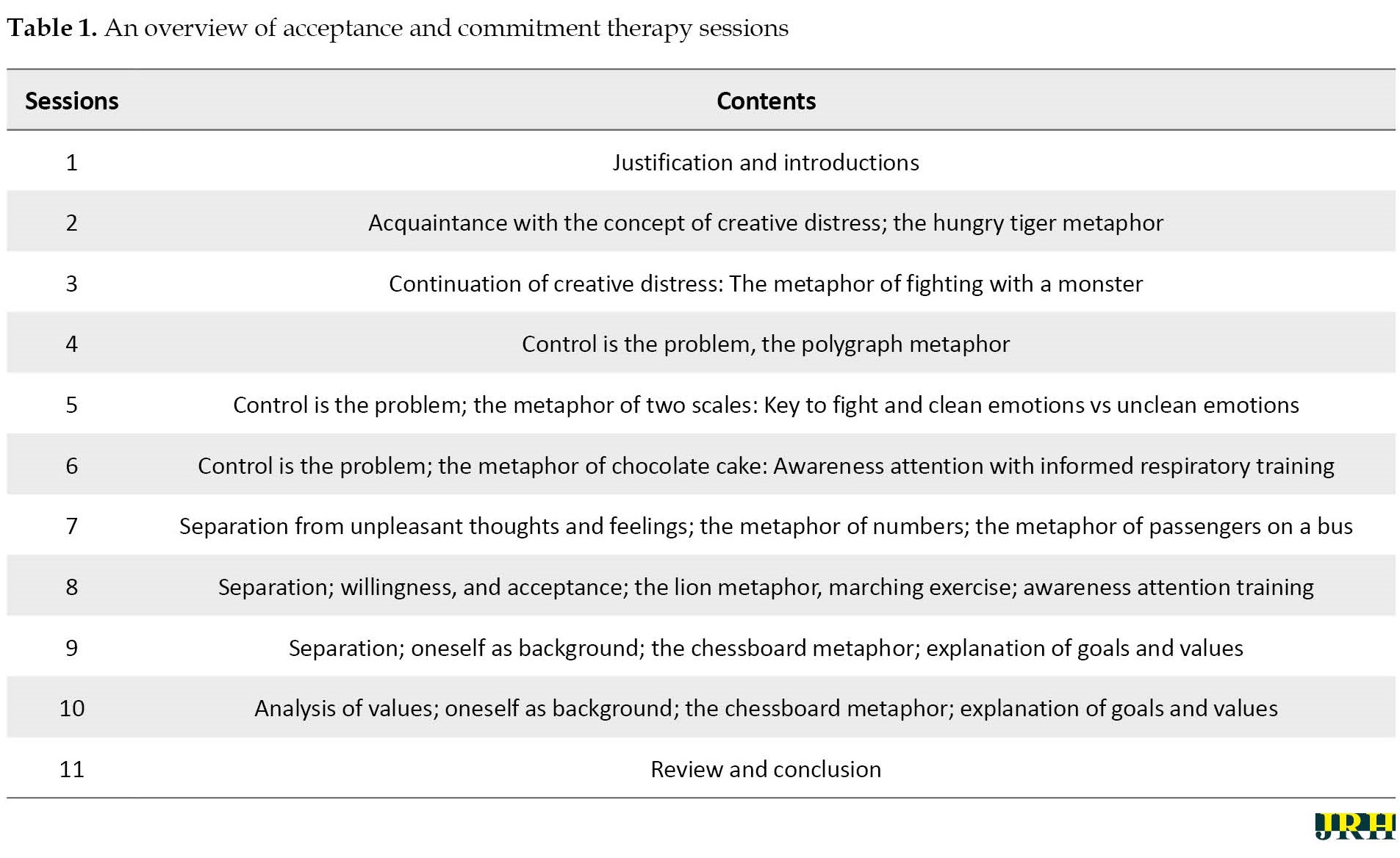

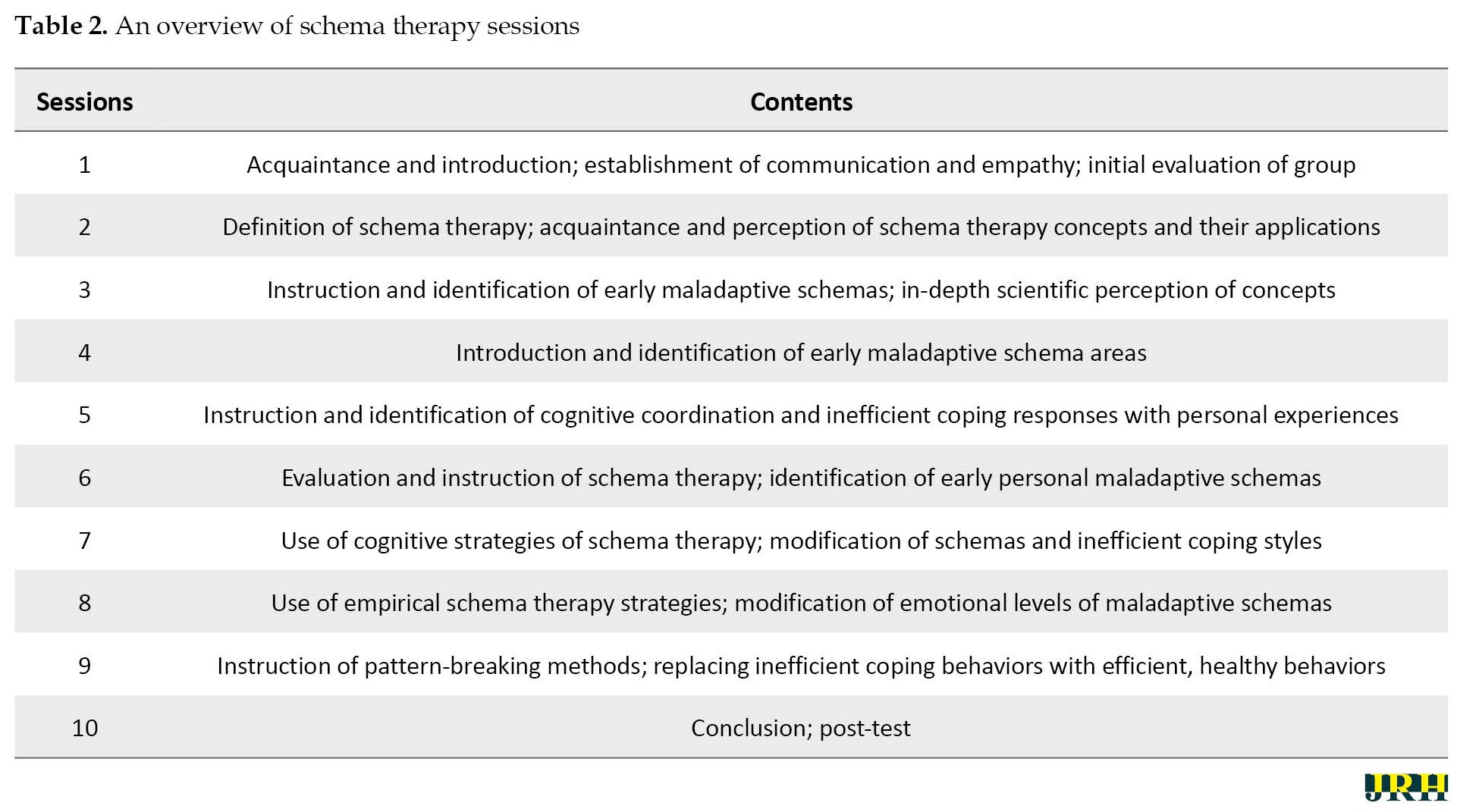

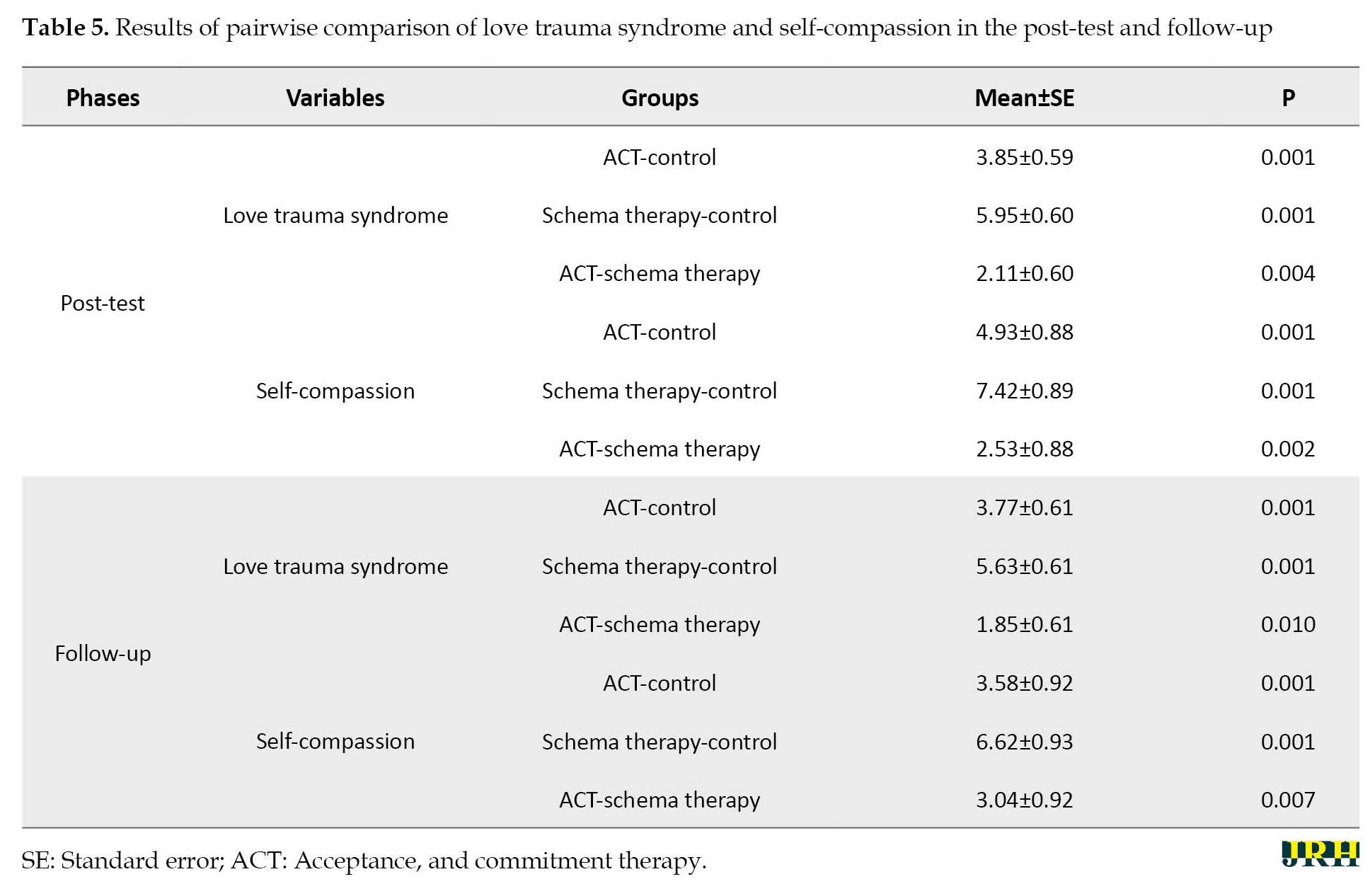

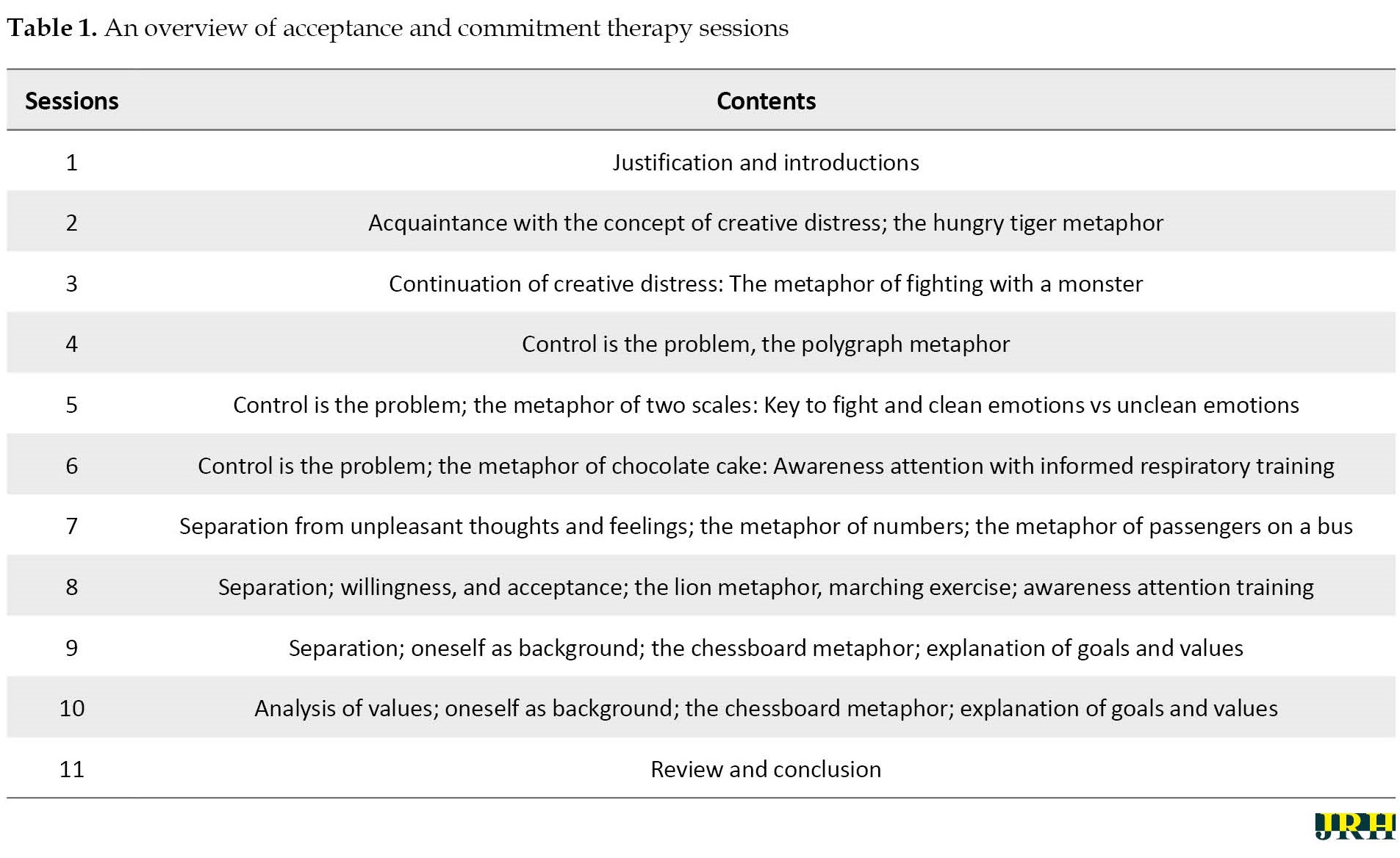

Firstly, specialized clinics of psychiatry and counseling in Ahvaz City, Iran, were asked for their cooperation. Unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns were identified among the patients visiting those clinics. After identifying sufficient cases, the researcher explained the research objectives and ethical considerations to the participants in an initial interview. Their questions were also answered, and they were asked to provide informed consent. After the initial interview, the participants were randomly assigned to 3 ACT, schema therapy, and control groups. Each experimental group received a few specific sessions based on relevant instructions; however, the control group received no interventions in the research period. In particular, the schema therapy group received ten 90-min therapy sessions in a week based on the protocol of Young et al. [40]. In contrast, the ACT group received eleven 90-min sessions in a week [41]. Tables 1 and 2 summarize therapy sessions in ACT and schema therapy groups.

Sharifi Nejad Rodani had attended related courses and workshops, and he conducted the therapy sessions at International Counseling Center in Ahvaz City, Iran. After the final sessions in the experimental groups, the research questionnaires were administered for the post-test, and 2-month follow-up stages were applied.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, Mean±SD and inferential statistics univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and multivariate ANCOVA were used for data analysis in the SPSS software, version 26. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted to evaluate the normal distribution, and the Levene test was used to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. The Bonferroni post hoc test was also used to compare the means.

3. Results

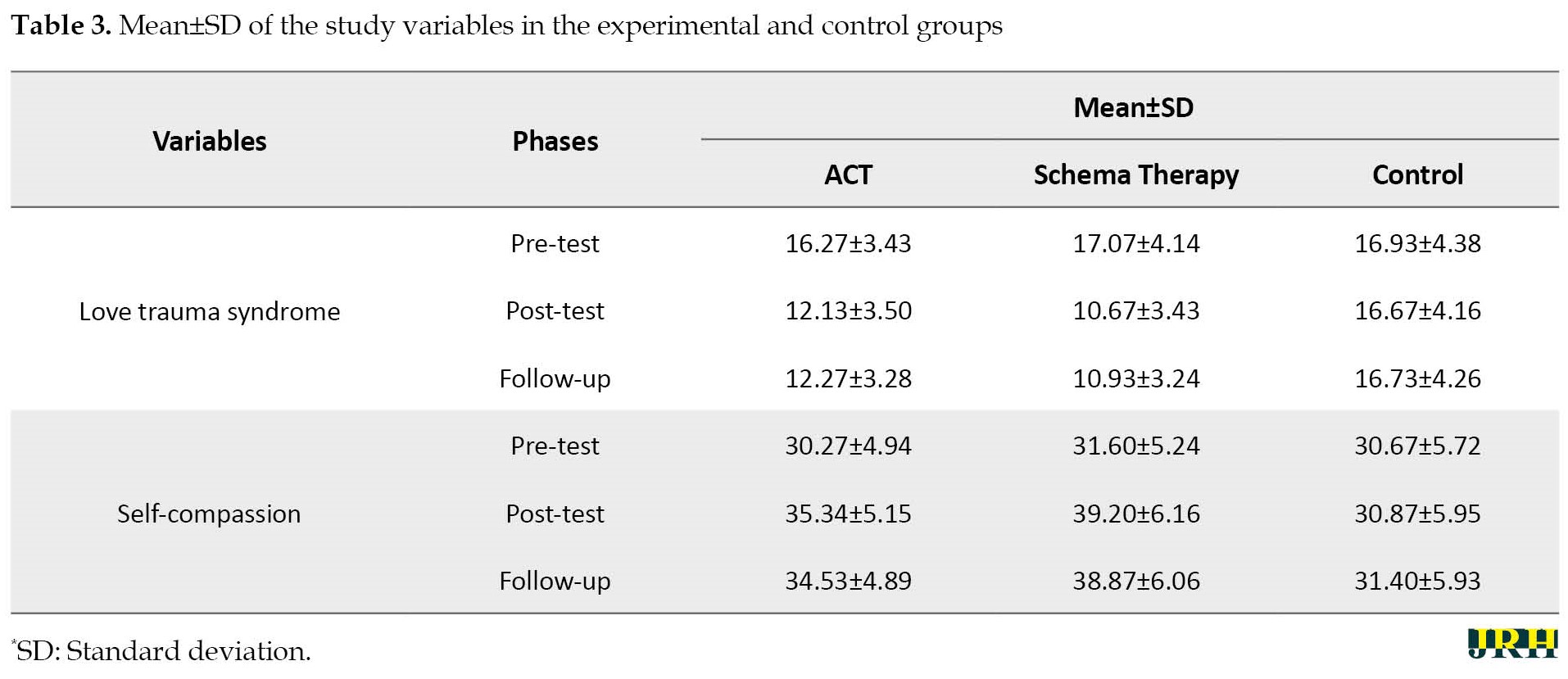

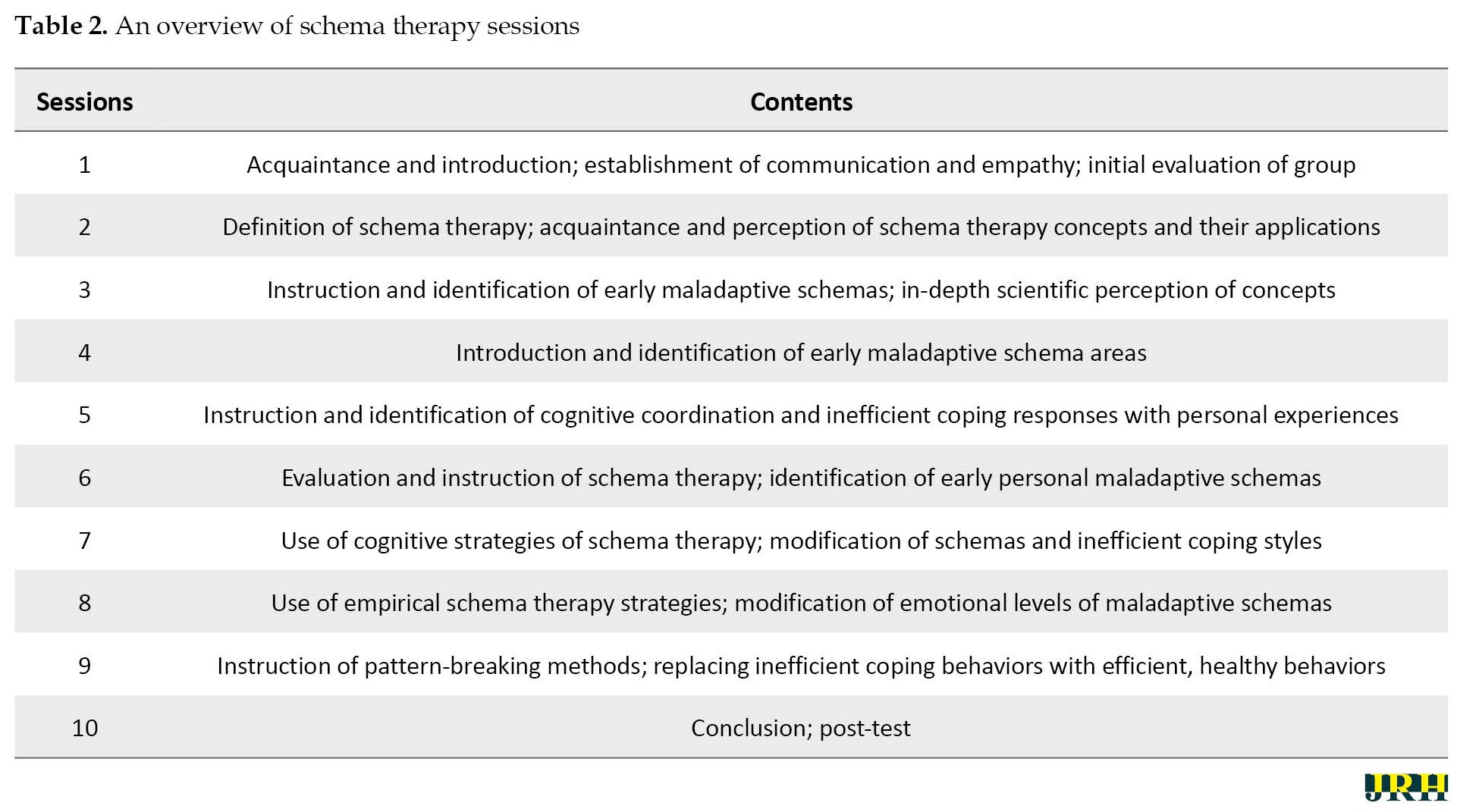

The Mean±SD age of the participants was 22.73±3.24 in the ACT group, whereas it was 25.33±3.697 in the schema therapy group. It was 24.53±3.292 in the control group. The Mean±SD duration of the relationship was 12.87±5.566) in the ACT group, whereas it was 17.07±6.616 in the schema therapy group. It was 14.8±5.168 in the control group. In the ACT group, 10(66.7%) and 5(33.3%) had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively. In the schema therapy group, 11(73.3%) and 4(26.7%) participants had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively. In the control group, 10(66.7%) and 5(33.3%) participants had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively. The Mean±SD of love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in the ACT, schema therapy, and control groups are provided in Table 3.

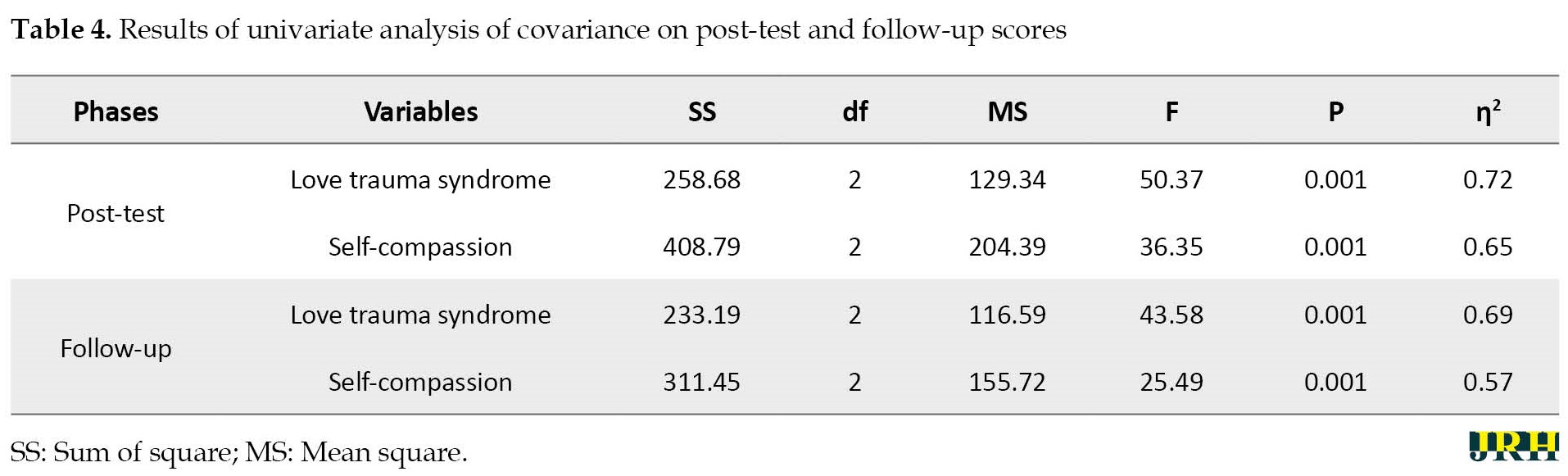

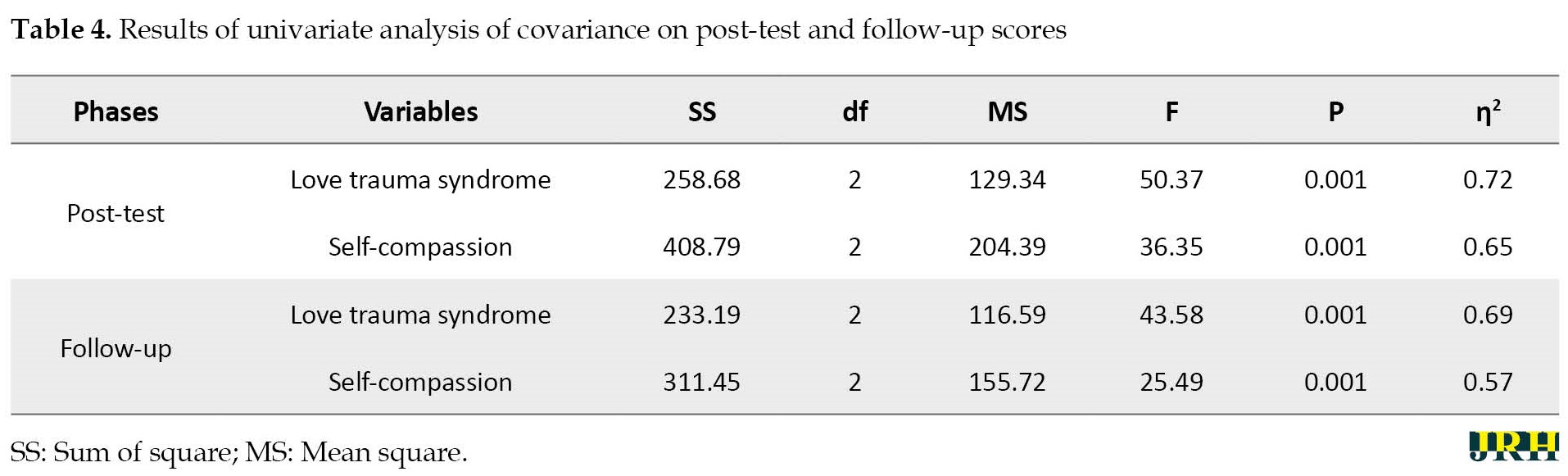

According to the Smirnov-Kolmogorov test results, the love trauma syndrome data (Z=0.172, P=0.211) and self-compassion (Z=0.140, P=0.189) follow the normal distribution. The results of the Levene test also established the homogeneity of the love trauma syndrome (F=0.663, P=0.289) and self-compassion (F=0.812, P=0.371). The results of multivariate ANCOVA in the ACT, schema therapy, and control groups indicated significant differences between groups in at least one dependent variable (P<0.001). Table 4 reports the results of univariate ANCOVA for post-test and follow-up variables independent variables.

According to the results, there were significant differences among ACT, schema therapy, and control groups in love trauma syndrome (df=2, F=50.38, P<0.001) and self-compassion (df=2, F=36.35, P<0.001) in the post-test stage. Moreover, there were significant differences among ACT, schema therapy, and control groups in love trauma syndrome (df=2, F=43.58, P<0.001) and self-compassion (df=2, F=25.49, P<0.001) in the follow-up stage.

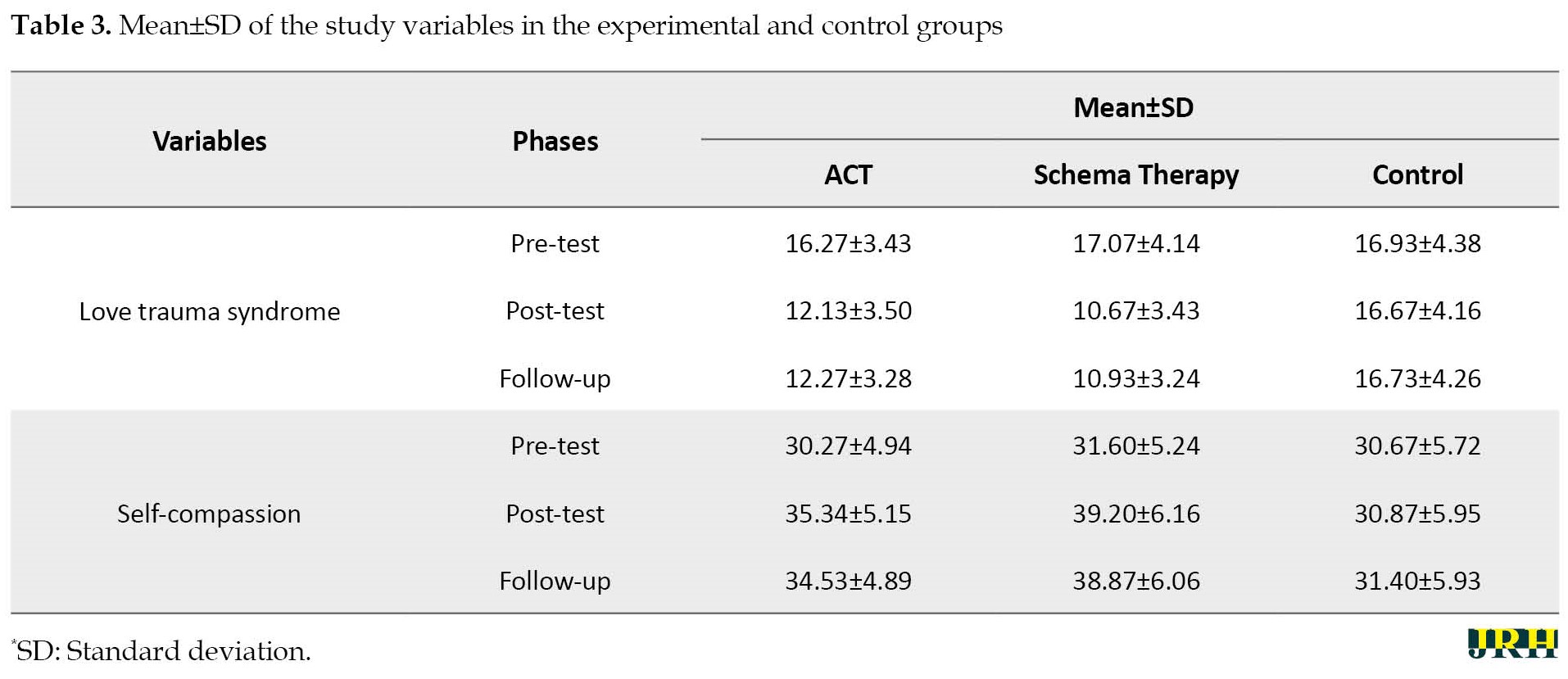

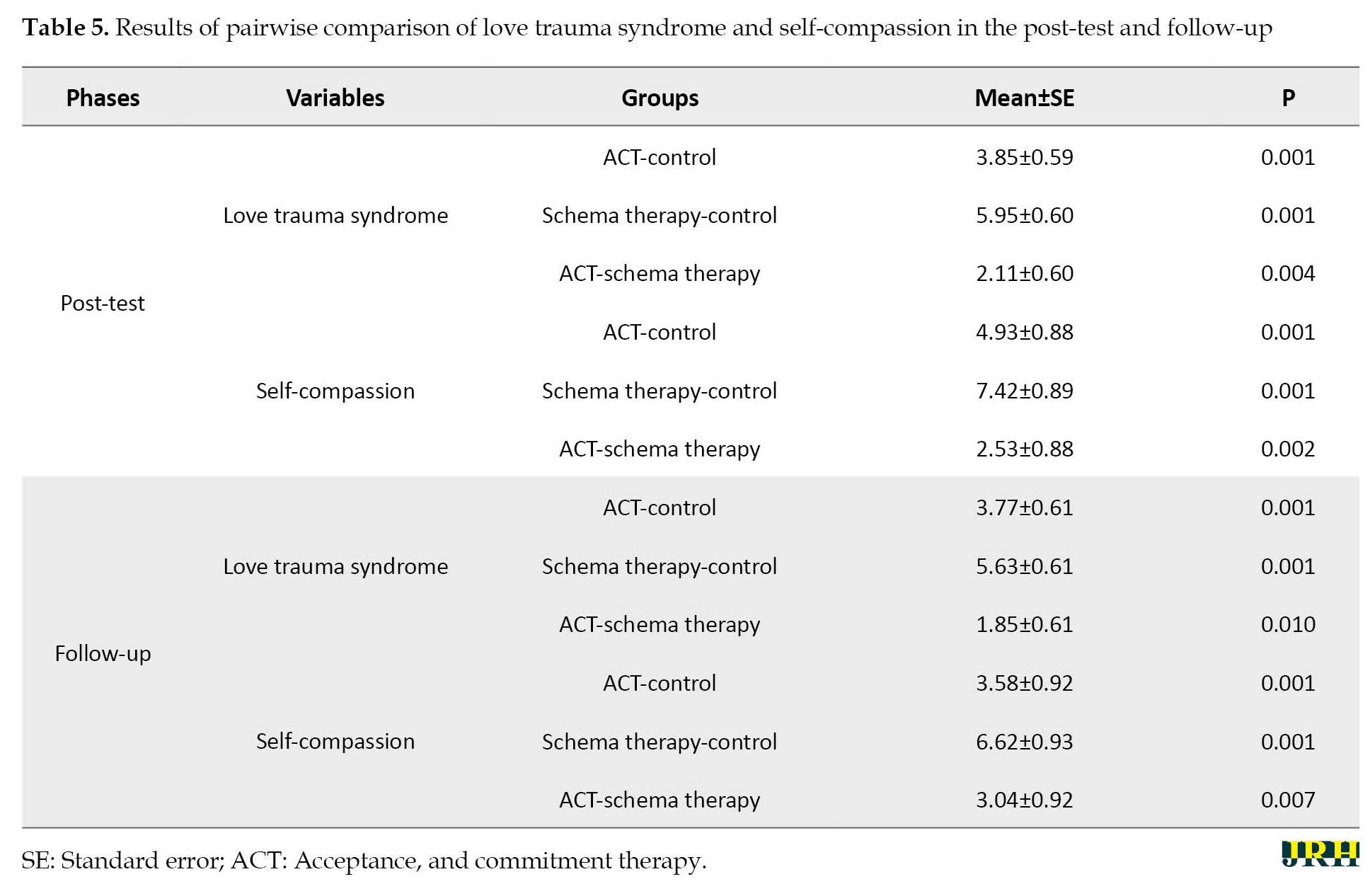

Table 5 presents the results of the post hoc Bonferroni test to compare the experimental groups and the control group in the means of studied variables on post-test and follow-up.

According to the results, there was a difference between the control and the experimental groups in love trauma syndrome and self-compassion (P<0.001). Moreover, a significant difference was observed between the ACT and schema therapy groups in love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in favor of the schema therapy group (P<0.01). According to the follow-up results, there were significant differences between the experimental and control groups (P<0.01). Hence, the effects of ACT and schema therapy on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion on unmarred girls with emotional breakdown persisted until the follow-up stage.

4. Discussion

This research compared the effectiveness of ACT and schema therapies on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. According to the results, there was a significant difference between the control group and the ACT group regarding love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns in favor of the ACT group.

This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies [42, 43]. Tabrizi et al. [42] reported that ACT effectively improved the psychological well-being of divorced women. Tracey et al. [43] reported that ACT effectively reduced the psychological distress of at-risk children. ACT has proven effective in treating adolescents with emotional breakdowns. Focusing on techniques of acceptance and concentration, ACT improves acceptance in girls experiencing an emotional breakdown. It helps participants accept emotional breakdown as an unpleasant event, making them less likely to think about failure [9]. This therapeutic approach also helps patients end struggles caused by emotional breakdown and love trauma syndrome. These individuals find themselves in an inevitable war where they must fight [24]. ACT teaches patients how to exit this war by encouraging them to consider themselves as a background. In ACT, a patient can perceive annoying or unpleasant experiences, make contact with some aspects of the situation, and effectively experience annoying events, such as love trauma syndrome. This therapeutic approach instructs patients on techniques for moving against and through obstacles.

Self-compassion increases in ACT, whereas self-judgment and isolation decrease. Self-compassion starts with sensitivity to the self-suffering and suffering of others. It is accompanied by the expansion of empathy and a mild willingness to mitigate the self-suffering and suffering of others by reducing self-blame and improving self-kindness [42]. Individuals with emotional breakdowns learn through ACT to alleviate their dissatisfaction with emotional breakdowns and befriend their physical and emotional pains, which they welcome as a good host. Reducing self-criticism and isolation, ACT teaches patients to avoid indulging in a feeling of failure instead of self-blame. In ACT sessions, patients learn to construct themselves through their original values and avoid comparison with others [28].

The results indicated a significant difference between the control and schema therapy groups regarding love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns in favor of the schema therapy group. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies [33, 44]. Shams et al. [33] reported that it effectively improved self-concept among obese. If people with emotional breakdowns fail to face reality by being lost in consequent problems, they will experience many psychological complications. In this approach, the participants see consequent problems of emotional breakdown, for instance, love trauma syndrome, as heterogeneous; hence, they become further motivated to be free from those problems [32]. Therapists team up with patients to fight schemas by adopting cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and interpersonal strategies. Therapists help patients compassionately face the reasons and necessities of encountering love trauma. Interacting with negative life events and causing cognitive vulnerability, maladaptive schemas prepare individuals with emotional breakdowns for inefficient attitudes, distress, and psychological disorders [29]. The presence of these schemas at the time of emotional breakdown would make individuals feel self-unkindness and self-anger. Cognitive schema therapy techniques allow individuals with emotional breakdowns to experience new opportunities through visualization and perception of transformational roots in schemas [33]. Schema therapy improves patients’ self-efficacy for self-compassion enhancement by increasing succession learning opportunities.

According to the results, there was a significant difference between the ACT and schema therapy groups in terms of love trauma syndrome in favor of schema therapy. In other words, the difference between ACT and schema therapy was confirmed in their effects on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. Although both approaches affected the love trauma syndrome and improved self-compassion, the reason for the greater effects of schema therapy might be its focus on cognitive function with an emphasis on emotions based on maladaptive schemas [33]. However, ACT monitors cognitive processes with an emphasis on intrinsic experiences. Since people with emotional breakdown experience problems with other people, schema therapy effectively changes states and symptoms.

Finally, the research limitations should be addressed. Both therapeutic approaches were conducted by one therapist, something which may cause bias. The statistical population and the research sample included only unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns in Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province, Iran; therefore, the generalization of results to other populations and genders will be limited. Another limitation of the current study was the lack of an intervention to neutralize the placebo effect of the treatment in the control group. It is recommended that future studies analyze male and female samples so that further information regarding the effective mechanisms of both therapeutic approaches can be obtained, in addition to an opportunity to draw gender-based comparisons.

5. Conclusion

ACT and schema therapy mitigated the love trauma syndrome and improved self-compassion among unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. According to the research results, schema therapy was more effective than ACT in alleviating the love trauma syndrome and improving self-compassion among unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. Therefore, it is beneficial to consider the research results and the roles of ACT and schema therapy in alleviating love trauma syndrome and improving self-compassion to hold training and psychotherapy workshops for unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns and help them achieve psychological well-being.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1400.161).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the study participants.

References

Establishing a stable, meaningful relationship is considered a critical social human capacity. Parent–infant bonds, child–parent bonds, infatuations in adolescence and youth, close friendships, and other human connections are essential for physical and mental health [1]. During childhood, relationships with parents are often described as the most important type of relationship [2, 3]. However, relationships with love partners gradually gain importance in adolescence and youth. Failure to establish and maintain close romantic relationships with commitment can hinder an individual’s development and adversely affect their well-being in life due to the potential emergence of serious problems [4]. In their romantic relationships, people experience higher levels of intimacy toward their partners than others. As a result, the stability and quality of these relationships can directly and indirectly affect psychological and physical health during their entire life [5]. Breaking up from a romantic relationship is among the most excruciating events that can occur in a person’s life. It has a substantial role in short-term and long-term adjustments [6]. Psychological disorders will emerge if the basic and emotional needs for establishing and forming high-quality and stable relationships are left unsatisfied [7, 8]. Verhallen et al. [6] reported that symptoms of depression are evident in people who have recent romantic relationship breakups.

Emotional breakdown leads to a very prevalent and deep experience of loss and sorrow. Failing or ending a romantic relationship in adolescence or youth is not unusual. Failure in a relationship has been introduced as a typical source of stress for university students [9]. Upon entering universities, students experience new dimensions of romantic relationships because they develop more specific emotional needs as they encounter a unique situation in which they are away from their families [10]. Moreover, they find opportunities to communicate with the opposite sex. The consequent traumas of romantic relationships have cognitive, emotional, physical, individual, and social dimensions [11]. Ghazinejad et al. [12] reported that girls with symptoms of love trauma syndrome would manifest maladaptive reactions, such as confusion, uncompromising decisions, bargaining, change of beliefs, cognitive distortions, and rumination.

Self-compassion is directly related to positive psychological health and can be defined as a positive self-stance. It is also considered an effective attribute and a protective factor for romantic flexibility [13]. Tiwari et al. [14] reported that self-compassion is a complex process bringing in cognitive, affective, and behavioral resources for the individual. According to research, self-compassion can improve a person’s coping ability to encounter failures [15]. Self-compassion means the feelings of self-care and self-kindness as well as perception and attitude without judgments on personal shortcomings and failures. It also means that personal experiences are included in typical human experiences [16]. Studies have reported that self-compassion strongly correlates with mental health and well-being [17, 18]. Pandey et al. [18] said that self-esteem and self-compassion have predictive strengths for hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Individuals with higher levels of self-compassion experience lower levels of depression, anxiety, rumination, and intellectual suppression than individuals lacking self-compassion. They also experience higher happiness, optimism, life satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, emotional quotient, coping skills, intelligence, and flexibility than those who severely criticize themselves [14, 19]. According to different studies, people with high self-compassion can resolve conflicts in relationships with their love partners through compromising solutions that meet the needs of their partners by establishing a balance [20-22]. Kaya et al. [23] reported that self-compassion significantly predicts both relationship satisfaction and conflict resolution styles in romantic relationships. Therefore, improving self-compassion using cognitive psychotherapy methods and psychological interventions can contribute to solving family conflicts and improving romantic relationships.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a therapeutic method that has been effective in helping adolescents with emotional breakdowns [9]. ACT identifies avoidance of pain and tension as the main problem that leads to inability and reduces life satisfaction [24]. According to ACT, avoidance occurs when negative thoughts and emotions severely affect behavior [25]. Hence, the critical method of ACT is to make patients encounter situations that have already been avoided. ACT changes a patient’s relationships with their thoughts and feelings so that they have no longer considered symptoms [26]. The ultimate goal is to change these painful thoughts and feelings from their previous forms, which are interpreted as harmful symptoms that prevent a meaningful and enriched life, to their new forms, which are interpreted as the natural experiences of humans that are considered part of a meaningful and enriched life [27, 28]. Because of these characteristics (acceptance without avoidance of adverse experiences), ACT can probably help girls with emotional breakdowns stop interpreting experiences as negative events. It can significantly improve their mental health in general. Noormohamadi et al. [9] reported that ACT improved mental health in students with an emotional breakdown. Meanwhile, Mohammadian et al. [26] reported that ACT effectively decreased cognitive avoidance and increased empathy in couples with low marital adjustment.

The presence of early maladaptive schemas can lead to an emotional breakdown [29]. Correlated with negative events in life, these schemas cause cognitive trauma and make people with emotional breakdowns vulnerable to inefficient attitudes, distress, and psychological disorders [30, 31]. Schema therapy is a novel, integrated approach mainly based on expanding classic cognitive-behavioral therapy methods and concepts [32]. Moreover, schema therapy has integrated the principles and foundations of cognitive-behavioral methods into attachment, gestalt, object relationships, constructivism, and psychiatry in a valuable conceptual therapy model [33]. Some early maladaptive schemas, such as emotional deprivation or attachment, play critical roles in the emergence of psychological disorders and symptoms of an emotional breakdown after failure in a romantic relationship [34]. Hence, schema therapy can significantly help such individuals by identifying and targeting these maladaptive schemas. Mohammadi et al. [35] reported that schema therapy effectively improved the components of marital conflict and reduced emotional reactions in women.

Emotional failure is introduced as one of the most painful experiences in life. Experiencing emotional failure leads to experiencing many negative emotions, such as anger and depression. If these emotions are not controlled in time, they can lead to more significant problems in life. In this situation, the best thing to do is to use professional psychotherapy services and get help from an experienced specialist. One of the current research innovations is comparing ACT and schema therapy interventions in girls with emotional breakdowns. The results of this study can be effective in choosing an effective method to control negative emotions and improve self-compassion in people with love failure. Accordingly, the present study compares the effectiveness of ACT and schema therapy on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns.

2. Methods

This quasi-experimental research adopted a pre-test-post-test design with a control group and follow-up. The statistical population included all unmarried girls experiencing an emotional breakdown in Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province, Iran, in 2022. The convenience sampling method was employed to select 45 available girls with an emotional breakdown in 2022. We included 15 girls with an emotional breakdown in each group using the G*Power software, version 3.1 with an effect size of 1.25, a test power of 0.95, and α of 0.05. They were then randomly assigned to an ACT, schema therapy, and control group. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Being in the age range of 18 to 30 years, having experienced an emotional breakdown, and being unmarried. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Having any psychological disorders, taking psychiatric drugs, having various short-term romantic relationships, having been married and divorced, and experiencing the death of a spouse.

Study measures

Love trauma inventory

Developed by Rosse [36], the love trauma inventory (LTI) checklist consists of 10 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 to 3). Items 1 and 2 are scored inversely. The scores of this checklist range from 0 to 30, as higher scores indicate more severe love traumas. The cut-off point is 20. The results of Etemadnia et al. [37] indicated the good validity of this questionnaire. Moreover, Etemadnia et al. [37] reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.83 for the Persian version of the questionnaire. In the current study, the Cronbach α for this instrument was obtained at 0.86.

Self-compassion scale–short form

Developed by Raes et al. [38], the self-comparison scale- short form (SCS–SF) includes 12 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1=never to 5=always) the scores on this scale range from 12 to 60. Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-kindness. The results of Shahbazi et al. [39] indicated the good validity of the SCS–SF. The total reliability of the scale was 0.91 using the Cronbach α coefficient, and its validity was significant at 0.001 [39]. The Cronbach α of this scale was 0.87 in the present study.

Study procedure

Firstly, specialized clinics of psychiatry and counseling in Ahvaz City, Iran, were asked for their cooperation. Unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns were identified among the patients visiting those clinics. After identifying sufficient cases, the researcher explained the research objectives and ethical considerations to the participants in an initial interview. Their questions were also answered, and they were asked to provide informed consent. After the initial interview, the participants were randomly assigned to 3 ACT, schema therapy, and control groups. Each experimental group received a few specific sessions based on relevant instructions; however, the control group received no interventions in the research period. In particular, the schema therapy group received ten 90-min therapy sessions in a week based on the protocol of Young et al. [40]. In contrast, the ACT group received eleven 90-min sessions in a week [41]. Tables 1 and 2 summarize therapy sessions in ACT and schema therapy groups.

Sharifi Nejad Rodani had attended related courses and workshops, and he conducted the therapy sessions at International Counseling Center in Ahvaz City, Iran. After the final sessions in the experimental groups, the research questionnaires were administered for the post-test, and 2-month follow-up stages were applied.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, Mean±SD and inferential statistics univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and multivariate ANCOVA were used for data analysis in the SPSS software, version 26. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted to evaluate the normal distribution, and the Levene test was used to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. The Bonferroni post hoc test was also used to compare the means.

3. Results

The Mean±SD age of the participants was 22.73±3.24 in the ACT group, whereas it was 25.33±3.697 in the schema therapy group. It was 24.53±3.292 in the control group. The Mean±SD duration of the relationship was 12.87±5.566) in the ACT group, whereas it was 17.07±6.616 in the schema therapy group. It was 14.8±5.168 in the control group. In the ACT group, 10(66.7%) and 5(33.3%) had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively. In the schema therapy group, 11(73.3%) and 4(26.7%) participants had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively. In the control group, 10(66.7%) and 5(33.3%) participants had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively. The Mean±SD of love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in the ACT, schema therapy, and control groups are provided in Table 3.

According to the Smirnov-Kolmogorov test results, the love trauma syndrome data (Z=0.172, P=0.211) and self-compassion (Z=0.140, P=0.189) follow the normal distribution. The results of the Levene test also established the homogeneity of the love trauma syndrome (F=0.663, P=0.289) and self-compassion (F=0.812, P=0.371). The results of multivariate ANCOVA in the ACT, schema therapy, and control groups indicated significant differences between groups in at least one dependent variable (P<0.001). Table 4 reports the results of univariate ANCOVA for post-test and follow-up variables independent variables.

According to the results, there were significant differences among ACT, schema therapy, and control groups in love trauma syndrome (df=2, F=50.38, P<0.001) and self-compassion (df=2, F=36.35, P<0.001) in the post-test stage. Moreover, there were significant differences among ACT, schema therapy, and control groups in love trauma syndrome (df=2, F=43.58, P<0.001) and self-compassion (df=2, F=25.49, P<0.001) in the follow-up stage.

Table 5 presents the results of the post hoc Bonferroni test to compare the experimental groups and the control group in the means of studied variables on post-test and follow-up.

According to the results, there was a difference between the control and the experimental groups in love trauma syndrome and self-compassion (P<0.001). Moreover, a significant difference was observed between the ACT and schema therapy groups in love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in favor of the schema therapy group (P<0.01). According to the follow-up results, there were significant differences between the experimental and control groups (P<0.01). Hence, the effects of ACT and schema therapy on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion on unmarred girls with emotional breakdown persisted until the follow-up stage.

4. Discussion

This research compared the effectiveness of ACT and schema therapies on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. According to the results, there was a significant difference between the control group and the ACT group regarding love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns in favor of the ACT group.

This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies [42, 43]. Tabrizi et al. [42] reported that ACT effectively improved the psychological well-being of divorced women. Tracey et al. [43] reported that ACT effectively reduced the psychological distress of at-risk children. ACT has proven effective in treating adolescents with emotional breakdowns. Focusing on techniques of acceptance and concentration, ACT improves acceptance in girls experiencing an emotional breakdown. It helps participants accept emotional breakdown as an unpleasant event, making them less likely to think about failure [9]. This therapeutic approach also helps patients end struggles caused by emotional breakdown and love trauma syndrome. These individuals find themselves in an inevitable war where they must fight [24]. ACT teaches patients how to exit this war by encouraging them to consider themselves as a background. In ACT, a patient can perceive annoying or unpleasant experiences, make contact with some aspects of the situation, and effectively experience annoying events, such as love trauma syndrome. This therapeutic approach instructs patients on techniques for moving against and through obstacles.

Self-compassion increases in ACT, whereas self-judgment and isolation decrease. Self-compassion starts with sensitivity to the self-suffering and suffering of others. It is accompanied by the expansion of empathy and a mild willingness to mitigate the self-suffering and suffering of others by reducing self-blame and improving self-kindness [42]. Individuals with emotional breakdowns learn through ACT to alleviate their dissatisfaction with emotional breakdowns and befriend their physical and emotional pains, which they welcome as a good host. Reducing self-criticism and isolation, ACT teaches patients to avoid indulging in a feeling of failure instead of self-blame. In ACT sessions, patients learn to construct themselves through their original values and avoid comparison with others [28].

The results indicated a significant difference between the control and schema therapy groups regarding love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns in favor of the schema therapy group. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies [33, 44]. Shams et al. [33] reported that it effectively improved self-concept among obese. If people with emotional breakdowns fail to face reality by being lost in consequent problems, they will experience many psychological complications. In this approach, the participants see consequent problems of emotional breakdown, for instance, love trauma syndrome, as heterogeneous; hence, they become further motivated to be free from those problems [32]. Therapists team up with patients to fight schemas by adopting cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and interpersonal strategies. Therapists help patients compassionately face the reasons and necessities of encountering love trauma. Interacting with negative life events and causing cognitive vulnerability, maladaptive schemas prepare individuals with emotional breakdowns for inefficient attitudes, distress, and psychological disorders [29]. The presence of these schemas at the time of emotional breakdown would make individuals feel self-unkindness and self-anger. Cognitive schema therapy techniques allow individuals with emotional breakdowns to experience new opportunities through visualization and perception of transformational roots in schemas [33]. Schema therapy improves patients’ self-efficacy for self-compassion enhancement by increasing succession learning opportunities.

According to the results, there was a significant difference between the ACT and schema therapy groups in terms of love trauma syndrome in favor of schema therapy. In other words, the difference between ACT and schema therapy was confirmed in their effects on love trauma syndrome and self-compassion in unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. Although both approaches affected the love trauma syndrome and improved self-compassion, the reason for the greater effects of schema therapy might be its focus on cognitive function with an emphasis on emotions based on maladaptive schemas [33]. However, ACT monitors cognitive processes with an emphasis on intrinsic experiences. Since people with emotional breakdown experience problems with other people, schema therapy effectively changes states and symptoms.

Finally, the research limitations should be addressed. Both therapeutic approaches were conducted by one therapist, something which may cause bias. The statistical population and the research sample included only unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns in Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province, Iran; therefore, the generalization of results to other populations and genders will be limited. Another limitation of the current study was the lack of an intervention to neutralize the placebo effect of the treatment in the control group. It is recommended that future studies analyze male and female samples so that further information regarding the effective mechanisms of both therapeutic approaches can be obtained, in addition to an opportunity to draw gender-based comparisons.

5. Conclusion

ACT and schema therapy mitigated the love trauma syndrome and improved self-compassion among unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. According to the research results, schema therapy was more effective than ACT in alleviating the love trauma syndrome and improving self-compassion among unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns. Therefore, it is beneficial to consider the research results and the roles of ACT and schema therapy in alleviating love trauma syndrome and improving self-compassion to hold training and psychotherapy workshops for unmarried girls with emotional breakdowns and help them achieve psychological well-being.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1400.161).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the study participants.

References

- Thomas PA, Liu H, Umberson D. Family relationships and well-being. Innovation in Aging. 2017; 1(3):igx025. [DOI:10.1093/geroni/igx025] [PMID]

- Gómez-López M, Viejo C, Ortega-Ruiz R. Well-being and romantic relationships: A systematic review in adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2415. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16132415] [PMID]

- Xia M, Fosco GM, Lippold MA, Feinberg ME. A developmental perspective on young adult romantic relationships: Examining family and individual factors in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2018; 47(7):1499-516. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-018-0815-8] [PMID]

- Dehestani M, Ghanbarian Sharabiani S, Nooripour R, Zanganeh F. Prediction of depression symptoms based on personality traits and romantic relationships among students. Journal of Research & Health. 2018; 8(2):173-81. [DOI:10.29252/jrh.8.2.173]

- Zhan S, Shrestha S, Zhong N. Romantic relationship satisfaction and phubbing: The role of loneliness and empathy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022; 13:967339. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.967339] [PMID]

- Verhallen AM, Renken RJ, Marsman JC, Ter Horst GJ. Romantic relationship breakup: An experimental model to study effects of stress on depression (-like) symptoms. Plos One. 2019; 14(5):e0217320. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0217320] [PMID]

- Gupta M, Sharma A. Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2021; 9(19):4881-9.[DOI:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.4881] [PMID]

- Price M, Hides L, Cockshaw W, Staneva AA, Stoyanov SR. Young love: Romantic concerns and associated mental health issues among adolescent help-seekers. Behavioral Sciences. 2016; 6(2):9. [DOI:10.3390/bs6020009] [PMID]

- Noormohamadi SM, Arefi M, Afshaini K, Kakabaraee K. The effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on the mental health of students with an emotional breakdown. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2019; 34(1):1-7. [DOI:10.1515/ijamh-2019-0096] [PMID]

- Pedrelli P, Nyer M, Yeung A, Zulauf C, Wilens T. College students: Mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry. 2015; 39(5):503-11. [DOI:10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9] [PMID]

- Wlodarski R, Dunbar RI. The effects of romantic love on mentalizing abilities. Review of General Psychology. 2014; 18(4):313-21. [DOI:10.1037/gpr0000020] [PMID]

- Ghazinejad N, Asayesh MH, Bahonar F. [Explanation of cognitive reactions in girls with love trauma syndrome: A phenomenological study (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e- Ravanshenasi Journal. 2020; 9(1):97-106. [Link]

- Egan SJ, Rees CS, Delalande J, Greene D, Fitzallen G, Brown S, et al. A Review of self-compassion as an active ingredient in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression in young people. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2022; 49(3):385-403. [DOI:10.1007/s10488-021-01170-2] [PMID]

- Tiwari GK, Pandey R, Rai PK, Pandey R, Verma Y, Parihar P, et al. Self-compassion as an intrapersonal resource of perceived positive mental health outcomes: A thematic analysis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2020; 23(7):550-69. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2020.1774524]

- Nazeri R, Lotfabadi H, Pourshahriar H. Effect and comparison of cognitive self-compassion and mindfulness on educational well-being of overweight students. Journal of Research & Health. 2019; 9(3):268-74. [DOI:10.29252/jrh.9.3.268]

- Homan KJ, Sirois FM. Self-compassion and physical health: Exploring the roles of perceived stress and health-promoting behaviors. Health Psychology Open. 2017; 4(2):2055102917729542. [DOI:10.1177/2055102917729542] [PMID]

- Min L, Jianchao N, Mengyuan L. The influence of self-compassion on mental health of postgraduates: Mediating role of help-seeking behavior. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022; 13:915190. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.915190] [PMID]

- Pandey R, Tiwari GK, Parihar P, Rai PK. Positive, not negative, self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-esteem and well-being. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2021; 94(1):1-15. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12259] [PMID]

- Alavi K. The role of social safeness and self-compassion in mental health problems: A model based on gilbert theory of emotion regulation systems. Practice in Clinical Psychology. 2021; 9(3):237-46. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.9.3.768.1]

- Parihar P, Tiwari GK, Rai PK. Understanding the relationship between self-compassion and interdependent happiness of the married Hindu Couples. Polish Psychological Bulletin. 2020; 51(4):260-72. [DOI:10.24425/ppb.2020.135458]

- Lathren CR, Rao SS, Park J, Bluth K. Self-compassion and current close interpersonal relationships: A scoping literature review. Mindfulness. 2021; 12(5):1078-93. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-020-01566-5] [PMID]

- Bolt OC, Jones FW, Rudaz M, Ledermann T, Irons C. Self-compassion and compassion towards one’s partner mediate the negative association between insecure attachment and relationship quality. Journal of Relationships Research. 2019; 10:e20. [DOI:10.1017/jrr.2019.17]

- Kaya F, Uluman OT, Sukut O, Balik CHA. The predictive effect of self-compassion on relationship satisfaction and conflict resolution styles in romantic relationships in nursing students. Nursing Forum. 2022; 57(4):608-14. [DOI:10.1111/nuf.12717] [PMID]

- Mousavi Haghighi SE, Pooladi Rishehri A, Mousavi SA. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and integrated behavioral couples therapy on intimacy and family functioning in divorce-seeking couples. Journal of Research & Health. 2022; 12(3):167-76. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.12.3.1972.1]

- Dindo L, Van Liew JR, Arch JJ. Acceptance and commitment therapy: A transdiagnostic behavioral intervention for mental health and medical conditions. Neurotherapeutics. 2017; 14(3):546-53. [DOI:10.1007/s13311-017-0521-3] [PMID]

- Mohammadian S, Asgari P, Makvandi B, Naderi F. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on anxiety, cognitive avoidance, and empathy of couples visiting counseling centers in Ahvaz City, Iran. Journal of Research & Health. 2021; 11(6):393-402. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.11.6.1889.1]

- Yin J. Effect of acceptance and commitment therapy combined with music relaxation therapy on the self-identity of college students. Journal of Healthcare Engineering. 2022; 2022:8422903. [DOI:10.1155/2022/8422903] [PMID]

- Motamedi H, Samavi A, Fallahchai R. Effectiveness of group-based acceptance and commitment therapy vs group-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in the psychological hardiness of single mothers. Journal of Research & Health. 2020; 10(6):393-402. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.10.6.1602.2]

- Tariq A, Quayle E, Lawrie SM, Reid C, Chan SWY. Relationship between early maladaptive schemas and anxiety in adolescence and young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 295:1462-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.031] [PMID]

- Chodkiewicz J, Wydrzyński M, Talarowska MJ. Young's Early maladaptive schemas and symptoms of male depression. Life. 2022; 12(2):167. [DOI:10.3390/life12020167] [PMID]

- Dehghan Sarvolia N, Dehghani A. Role of early maladaptive schemas and attachment styles in the prediction of thoughtful rumination in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Research & Health. 2019; 9(7):568-74. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.1442.1]

- Tan YM, Lee CW, Averbeck LE, Brand-de Wilde O, Farrell J, Fassbinder E, et al. Schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study of patients' perceptions. Plos One. 2018; 13(11):e0206039. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206039] [PMID]

- Shams Azar L, Ghahari S, Shahbazi A, Ghezelseflo M. Effect of group schema therapy on physical self-concept and worry about weight and diet among obese women. Journal of Research & Health. 2018; 8(6):548-54. [DOI:10.29252/jrh.8.6.548]

- Kunst H, Lobbestael J, Candel I, Batink T. Early maladaptive schemas and their relation to personality disorders: A correlational examination in a clinical population. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2020; 27(6):837-46. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2467] [PMID]

- Mohammadi S, Hafezi F, Ehteshamzadeh P, Eftekhar Saadi Z, Bakhtiarpour S. Effectiveness of schema therapy and emotional self-regulation therapy in the components of women’s marital conflicts. Journal of Client-centered Nursing Care. 2020; 6(4):277-88. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.6.4.341.1]

- Rosse RB. The love trauma syndrome: free yourself from the pain of a broken heart. Paris: Hachette Books; 2007. [Link]

- Etemadnia M, Shiroodi Sh, Khalatbari J, Abolghasemi Sh. [Predicting love trauma syndrome in college students based on personality traits, early maladaptive schemas, and spiritual health (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2021; 27(3):318-35. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.27.2.1096.2]

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2011; 18(3):250-5. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.702] [PMID]

- Shahbazi M, Rajabi G, Maghami E, Jelodari A. [Confirmatory factor analysis of the persian version of the self-compassion rating scale-revised (Persian)]. Psychological Methods and Models. 2015; 6(19):31-46. [Link]

- Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME. Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Link]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Springer. 2004. [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-23369-7]

- Tabrizi F, Ghamari M, Bazzazian S. [The comparison of effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with Integrating Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Compassion Focus Therapy on psychological well-being of Divorced Women (Persian)]. Journal of Counseling Research. 2020; 19(75):65-87. [DOI:10.29252/jcr.19.75.65]

- Tracey D, Gray T, Truong S, Ward K. Combining acceptance and commitment therapy with adventure therapy to promote psychological wellbeing for children at-risk. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018; 9:1565. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01565] [PMID]

- Faustino B, Vasco AB, Silva AN, Marques T. Relationships between emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion and unconditional self-acceptance on the regulation of psychological needs. Research in Psychotherapy. 2020; 23(2):145-56. [DOI:10.4081/ripppo.2020.442]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2023/03/3 | Accepted: 2023/05/20 | Published: 2023/10/3

Received: 2023/03/3 | Accepted: 2023/05/20 | Published: 2023/10/3

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |