Volume 14, Issue 3 (May & Jun 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(3): 259-268 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadeghi N, Sepahmansour M, Kouchak Etezar R. Reality Therapy Effect on Alexithymia and Posttraumatic Growth in Women With Love Failure. J Research Health 2024; 14 (3) :259-268

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2307-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2307-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ,Mojgan.sepahmansour@iauctb.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 658 kb]

(1077 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3300 Views)

Full-Text: (1225 Views)

Introduction

Love trauma syndrome is a set of severe signs and symptoms that appear after the breakup of a romantic relationship. It lasts long, disrupts a person’s performance in many fields (social, academic, and professional), and leads to maladaptive reactions [1]. Some symptoms have been shown to accompany emotional failure, including physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral difficulties [2]. When a relatively stable emotional relationship ends, very different feelings can arise. Although each person is unique, most people experience various stages of the phenomenon of loss [1]. An individual’s experiences after an emotional breakdown can include a wide range of emotions such as feelings of anger, sadness, depression, loneliness, anxiety and insomnia, physical symptoms, and ultimately, the breakdown of mutual trust and difficulty in re-establishing relationships with others [3]. Some believe that personality and emotional characteristics help understand romantic relationships, their quality, and positive and negative correlations with sentimental health and failure [4].

A review of the literature shows that one of the significant losses of people suffering from emotional failure is damage to the regulation and expression of emotions [5]. Alexithymia is a critical concept investigating issues related to emotion processing and regulation [6]. One underlying factor behind interpersonal problems is alexithymia [7]. A person with alexithymia has four distinct characteristics: Difficulty recognizing and describing emotions, difficulty distinguishing between emotions and physical stimuli, poor fantasy content, objective thinking, and weak introspection (extroverted thinking) [8]. The definition of alexithymia does not align with efficient emotion regulation, and researchers have shown that alexithymia is associated with ineffective emotion regulation [9]. For example, people with alexithymia are more likely to use suppression strategies and have less reappraisal than ordinary people. Among the two strategies mentioned, suppression strategies are more related to mental and physical health concerns and, therefore, are considered incompatible strategies to regulate emotions [10]. Ledermann et al. (2020) also showed that alexithymia was more common in people who had experienced trauma; therefore, paying attention to alexithymia and improving it among people suffering from emotional failure was necessary [11].

On the other hand, a traumatic experience such as an emotional failure can have a positive effect on a person, which is known as posttraumatic growth (PTG) [12]. Over the past decades, researchers have moved away from an exclusive focus on the negative aftermath following traumatic events. A growing body of studies document positive psychological changes after traumatic events [13, 14]. Tedeschi and Calhoun [15] referred to this phenomenon as PTG. It emphasizes the transformative quality of responding to traumatic events. The positive changes entail several domains, including perceived changes in self, a changed sense of relationship with others, and a changed philosophy of life. This concept refers to the positive personal and psychological changes after a severe and bitter event because the individual struggled against this stressful event, which has adaptive significance [15]. Breakup distress has generally been described in terms of stress and coping, suggesting a simple process to endure [16]. A recent alternative conceptualization called PTG has emerged, which interprets this distress as a more positive and growth-oriented process. PTG theory hypothesizes that traumatic experiences can promote “real life-transforming changes that go beyond illusion”[17].

A previously conducted meta-analysis of 26 studies demonstrated that 10% and 77.3% of participants experienced PTG [18]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of PTG identified that it is not associated with depression or anxiety [19]. Instead, it may coincide with depression and anxiety or exist in place of it. Thus, PTG is part of a complex system of outcomes related to trauma. If PTG can be enhanced after relationship dissolution, it will have important implications for understanding skills and relationship maintenance. Suppose people experience personal growth after a breakup. In that case, this growth can foster more successful relationships in the future and confer a developmental advantage to having multiple dating partners before long-term commitment [17].

Therefore, identifying effective interventions can help people, especially those who have experienced emotional failure. Many treatments have been recommended for people who go to a specialist because of their emotional breakdown syndrome, and these treatments fall into the two categories of psychotherapy and drug therapy [1]. Reality therapy is one treatment that increases resilience and emotional regulation strategies. The ability to accept reality, make ethical and responsible choices, build healthy relationships based on internal control, and live a prosperous and happy life. In reality therapy, symptoms and diseases are creative solutions for people to satisfy their needs, and the continuation of these methods. However, this therapy involves harm and suffering, showing their effect in fulfilling the needs [20]. Reality therapy is a method based on action. The therapist, along with the client, will create an acquirable program containing several positive stages, which will put him in the direction of satisfaction of the needs; the acronym WDEP (wants, direction, self-evaluation, planning) for describing methods executed in reality therapy [21].

In this approach, first, participants receiving reality therapy are asked to identify the goal of their behavior (e.g. seeking relaxation after a stressful study day). Second, they are asked what they are doing (for example, playing). Third, it educates them on whether their behavior advances or hinders progress toward the initial goal (e.g. playing may help relieve immediate stress, but excessive playing may interfere with study and health; as a result, it leads to more stress). Finally, it encouraged them to look for more suitable and superior options to replace the current behavior to achieve the goal and to plan to change the undesirable behavior (e.g. exercise instead of playing when feeling stressed) [22]. Tavasoli et al. investigated the effect of the group reality therapy approach on the symptoms of emotional failure and measured the overall performance of emotionally failed people. The results showed that group reality therapy reduced the symptoms of love failure and increased their overall performance score. Because group reality therapy increases a person’s responsibility and sense of control over his or her life, group reality therapy can be viewed as an effective method of reducing the symptoms of emotional failure and increasing an individual’s overall performance [23]. The results of another study revealed reality group therapy was effective in reducing the attitudes toward the opposite sex in female students with love trauma [24]. Thus, the authors conducted this study to determine the effectiveness of reality therapy on alexithymia and PTG in women with love failure.

Methods

This study was quasi-experimental research using a pre-test-post-test with a follow-up design. The statistical population of the present study comprised all the women with emotional failure experiences referred to Aramandish and Chaman clinics in Tehran City, Iran, during 2021 and 2022. The research involved the mentioned population, which met the inclusion criteria. A purposive sampling method was used to select the participants. The sample consisted of 20 women per group, calculated by G*Power software, version 3.1.9.7, with effect size=0.95, α=0.05, and test power=0.90 [24]. The participants in the research were divided into the experimental and control groups using a table of random numbers. In this method, even numbers were considered for the reality therapy group, and odd numbers were considered for the control group. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the experimental or control groups according to the odd or even number allocation. After dropping some samples, each group was composed of 15 participants (experimental and control groups). The inclusion criteria include the occurrence of non-marital emotional breakdown in the last six months (which was measured through a history), being 20 to 25 years old (a review of past research shows that emotional breakdown studies are often conducted at these ages), getting a score higher than 20 in the love trauma inventory, a score higher than 75 in the Toronto alexithymia scale, a score lower than 53 in the posttraumatic growth questionnaire, having at least a high school diploma (for reading and writing), and not suffering from psychological disorders such as depression, borderline personality, and obsession. Among the criteria for withdrawing from a research study are missing more than two sessions during the treatment period, getting involved in a new love relationship, or receiving treatment outside the study (self-administration or a psychiatrist’s prescription).

Because of gathering information from the Aramandish and Chaman clinics, we selected the desired applicants from there according to the inclusion criteria. As part of this research, the following actions were taken to respect the ethical concerns of the participants. At the beginning of the investigation, we collected informed consent from the participants after describing the research purposes. Before implementing the main treatment sessions, a meeting was held to explain the research, establish a good relationship, conduct a pre-test (Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS) and posttraumatic growth questionnaire), and collect information about the problems that confused them. In particular, a pre-test for alexithymia and posttraumatic growth was administered to the experimental group. Then Glasser’s [22] reality therapy intervention plan, whose validity has been confirmed by experts in this field, was applied to the experimental group in eight sessions of 90 minutes each, while the control group did not receive an intervention (Table 1).

The intervention sessions were implemented separately by each therapist within each center. Promptly after the completion of the interventions for the experimental group, the post-test of the research questionnaires was conducted for both groups. In the next step, two months after the post-test, the follow-up test was performed on both groups. Then, the results obtained in the post-test stage were analyzed by variance analysis with repeated measurements and covariance analysis using SPSS software, version 26. Before analyzing variance with repeated measurements, the results of Box’s M, Mauchly’s sphericity, and Levene’s tests were checked to comply with the statistical assumptions. According to the outcomes of Levene’s test, none of the variables were significant. Therefore, the assumption of the equality of variances between groups was respected, and the amount of error variance of dependent variables was equal in all groups.

Research tools

TAS

The alexithymia scale is a 20-item scale created by Bagby et al. [25] and evaluated alexithymia in three subscales: Difficulty in recognizing feelings (7 questions), difficulty in describing feelings (5 questions), and extraverted thinking (8 questions). Based on this scale, there are 5 possible answers: Totally disagree (1), disagree (2), neither disagree nor agree (3), agree (4), and totally agree (5). Bagbi et al. (1994) confirmed the self-validity of this tool and reported its reliability as 0.90. The validity of the Persian version of the TAS was found by the content validity ratio (CVR) as 0.88 and content validity index (CVI) as 0.82. Basharat [26] reported the validity of the entire scale in the Iranian sample was 0.71 and 0.83, and the scale’s validity was 0.85. For difficulty recognizing feelings, difficulty describing feelings, and extraverted thinking, the Cronbach α was used to calculate scale reliability coefficients of 0.83, 0.79, and 0.82, respectively. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.81

Posttraumatic growth inventory (PTGI)

Tedeschi and Calhoun designed the scale to evaluate the positive outcomes reported by people who experienced traumatic events [27]. This scale has 21 items with a 6-point Likert scale, which includes new possibilities, communication with others, personal power, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. The total scale scores of 105 and higher grades show higher posttraumatic growth. Tedeschi and Calhoun [27] reported that the posttraumatic growth scale has acceptable validity and reliability. In this study, ten experts confirmed the validity of the Persian version of this questionnaire (CVI=0.90, CVR=0.86). Heidarzadeh examined the reliability and validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire [28], confirming the 5-factor structure of the PTGI. The reported internal consistency was 0.87, and it ranged from 0.57 to 0.77 for the five dimensions. The test re-test correlation with a 30-day interval in 18 patients was 0.75. We also examined and confirmed the reliability of the questionnaire (α=0.92). In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.84.

Results

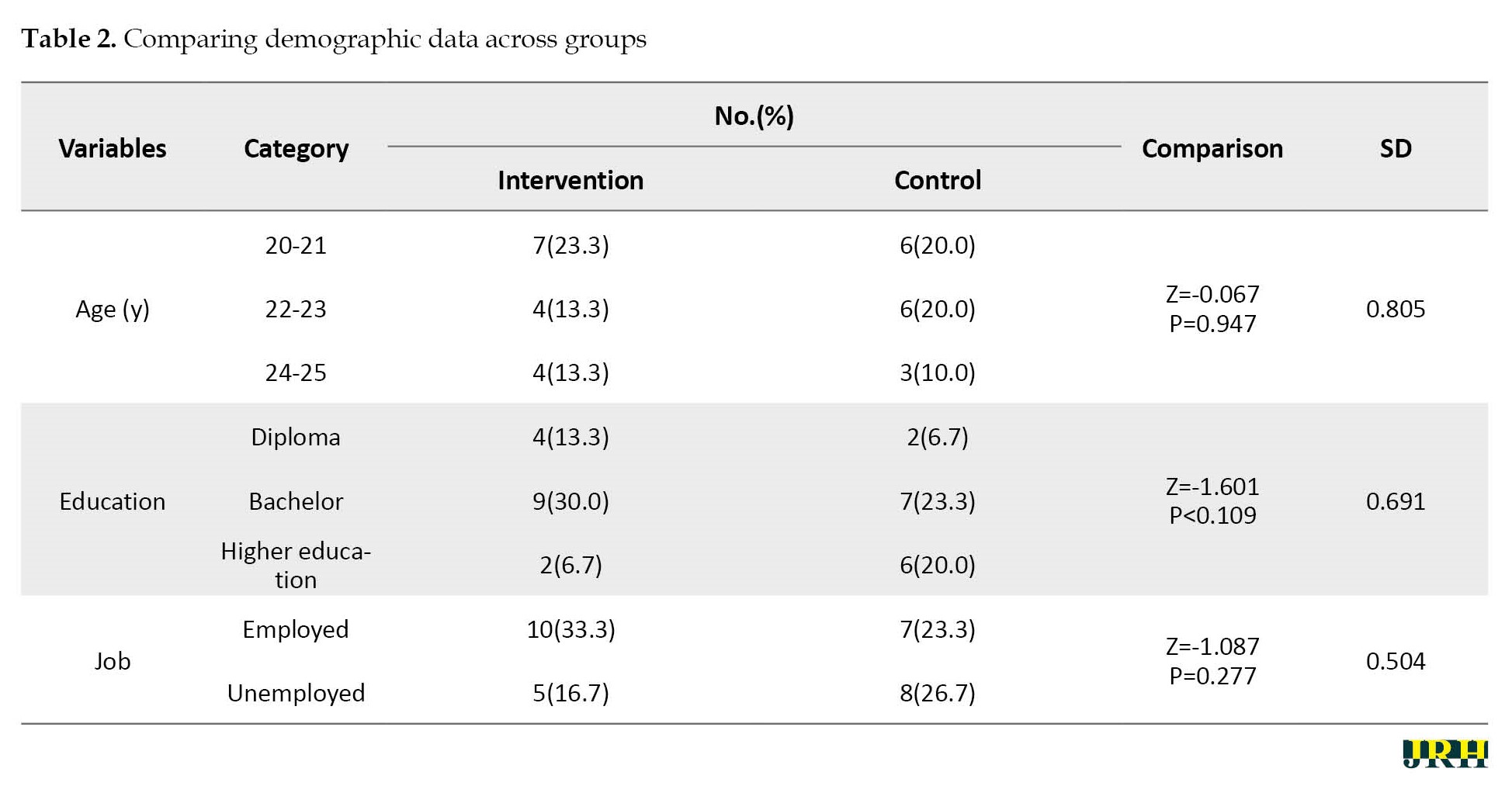

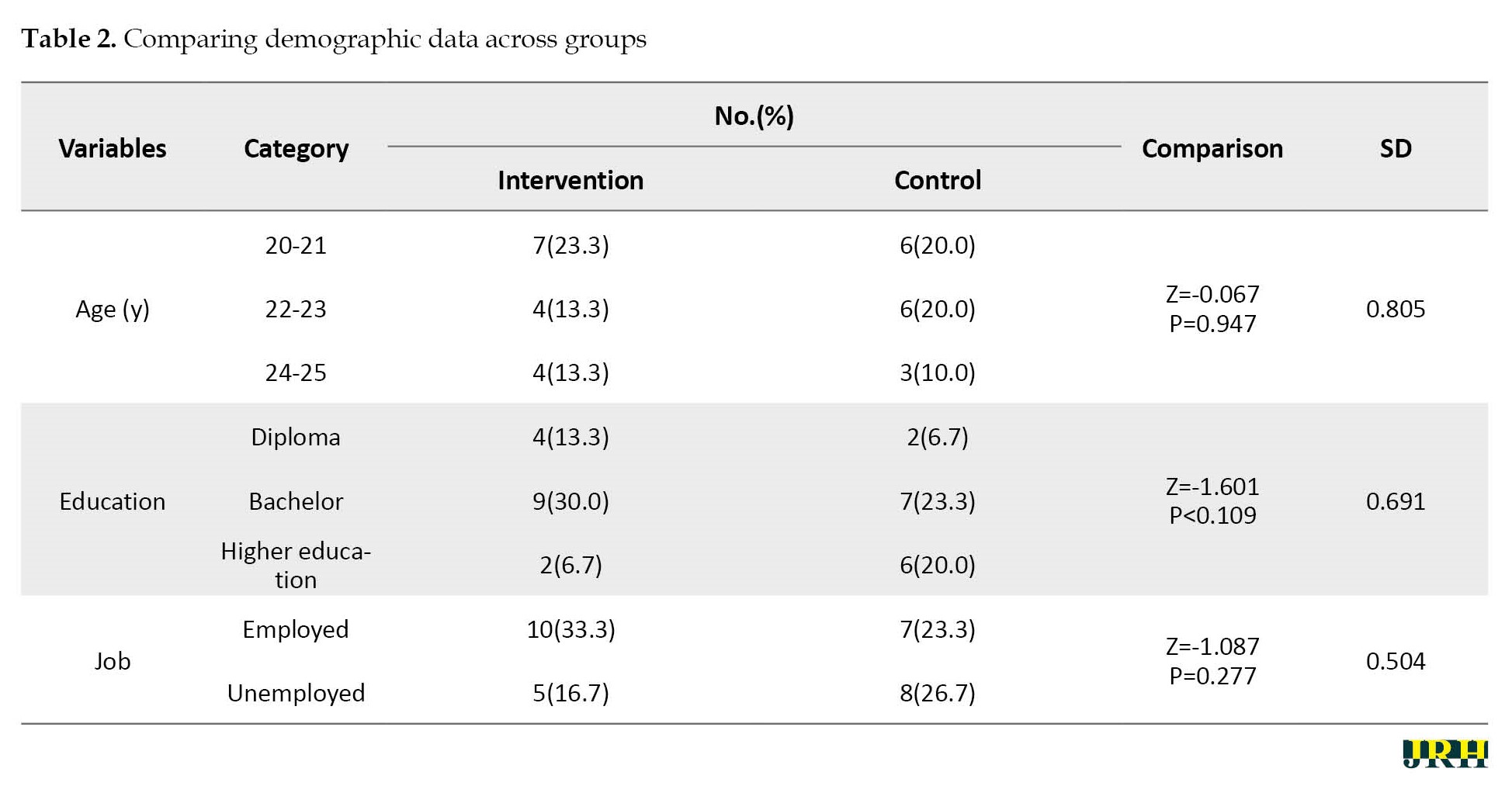

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis in SPSS software, version 26. According to Table 2, the majority of participants (23.3%) were in the age group of 20-21 years in the experimental group.

In the control group, both age groups of 20-21 and 22-23 (20%) years were equal. Most participants had bachelor’s degrees in the experimental group (30.0%) and in the control group (23.3%). Regarding occupation, 33.3% of people were employed in the experimental group, and 23.3% were employed in the control group. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed no significant difference between the groups in terms of age, education, and occupation (P>0.05 for all).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data. In addition, Levene’s test was used to check the homogeneity of variances. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the significance of the differences in the alexithymia and posttraumatic growth in women with love failure scores between the experimental and control groups. After comparing the post-test and follow-up scores to the pre-test results, there is a significant difference between alexithymia (F=31.014, P<0.0001) and posttraumatic growth (F=103.979, P<0.0001).

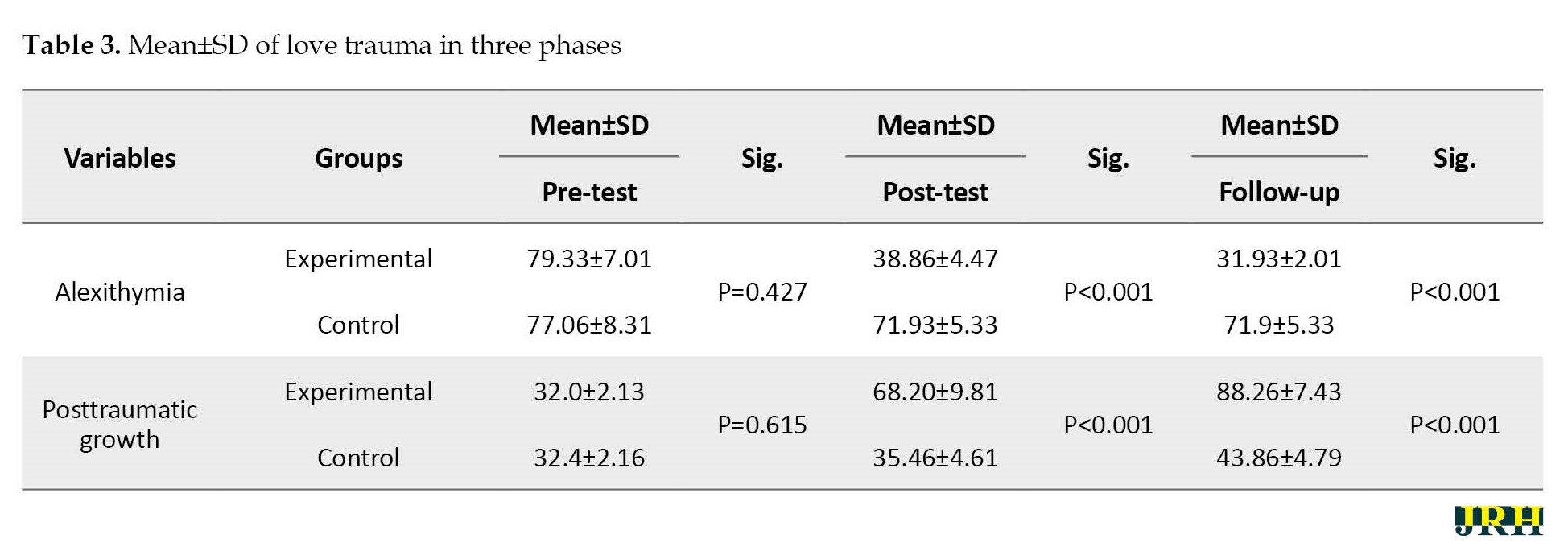

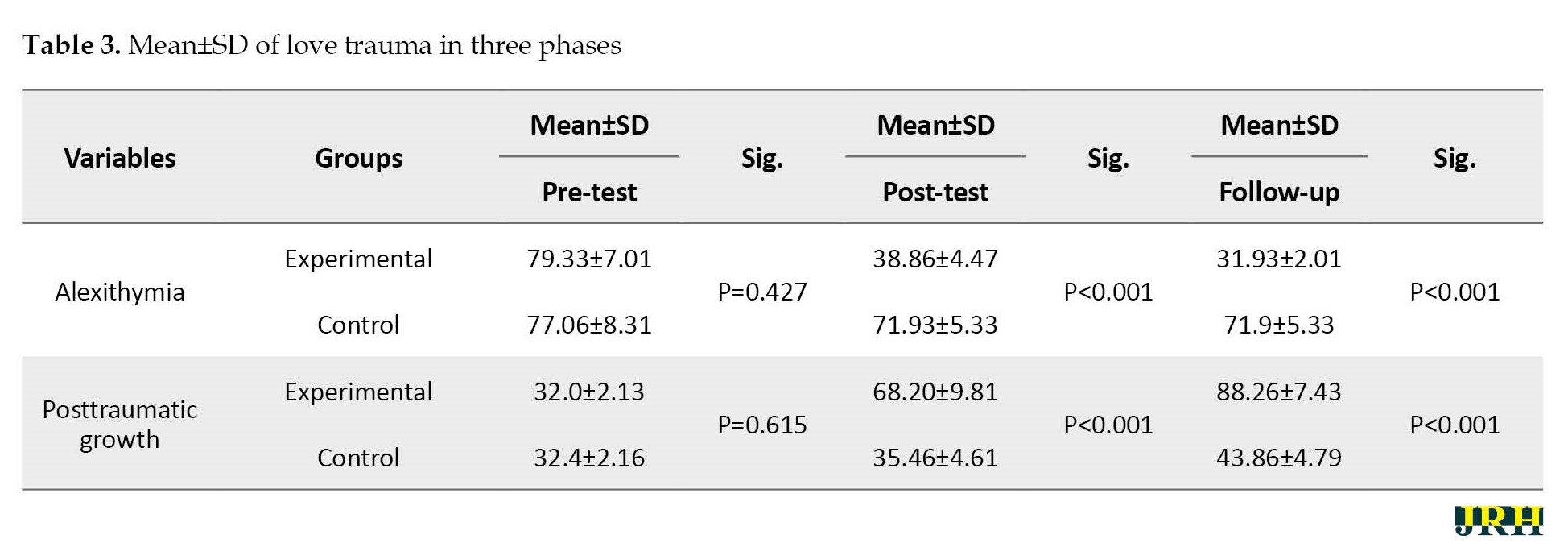

The researcher then used the ANCOVA method to compare the Mean±SD of the variables in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages, as shown in Table 3.

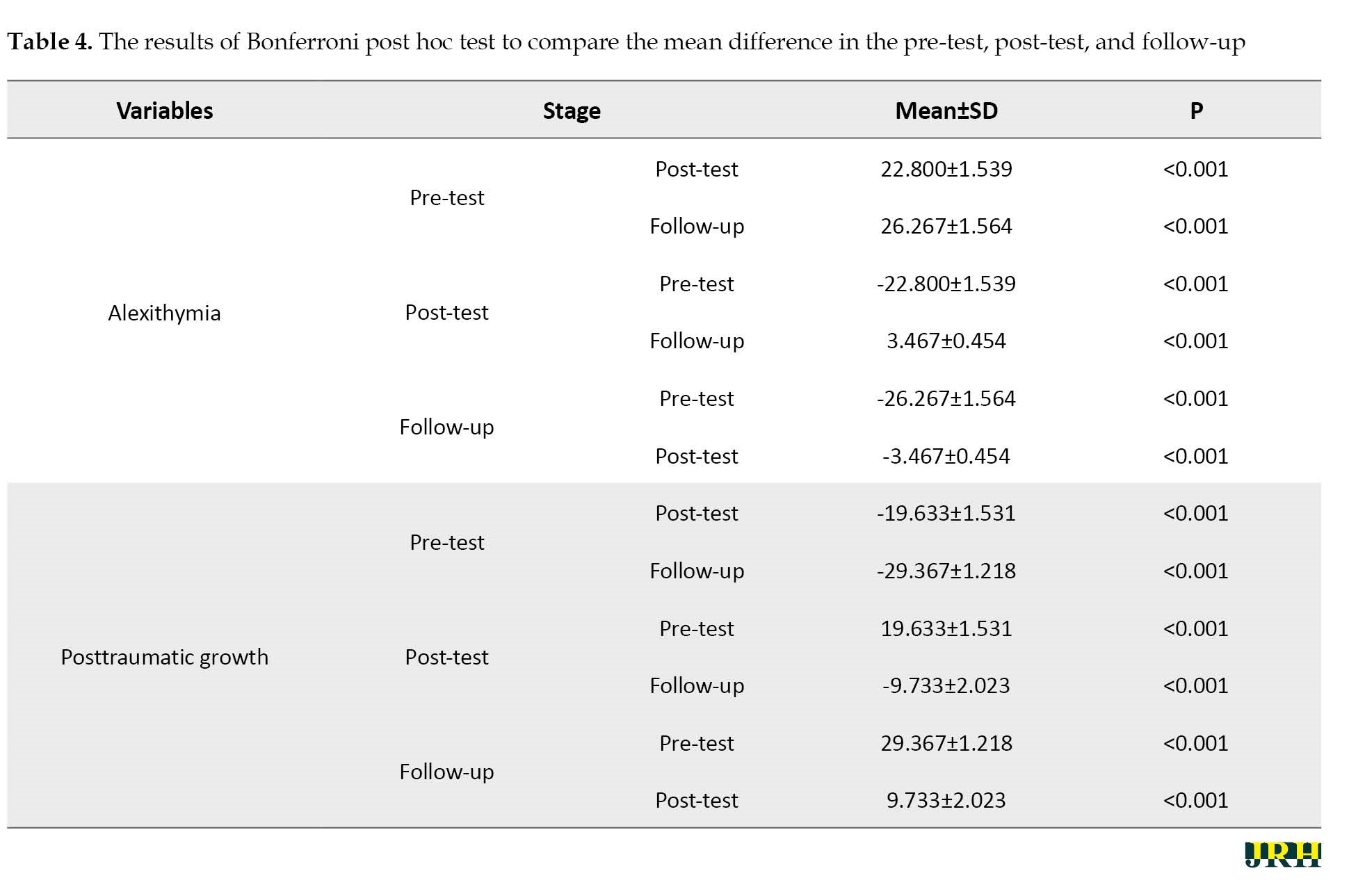

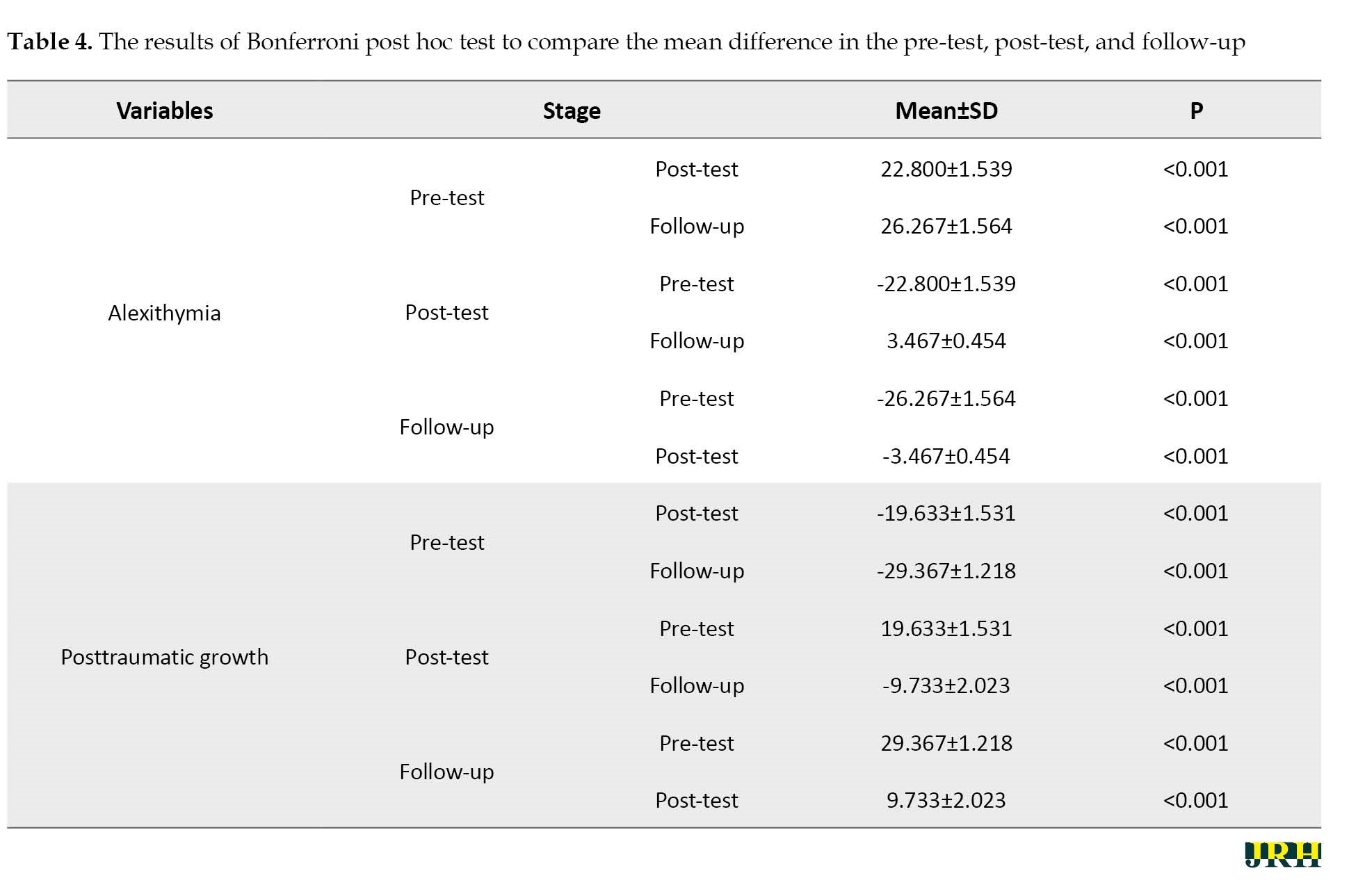

Using the Bonferroni test to compare the pre-test and post-test scores of love trauma syndrome and alexithymia, a significant difference was found between the pre-test and post-test scores (P<0.001) (Table 4).

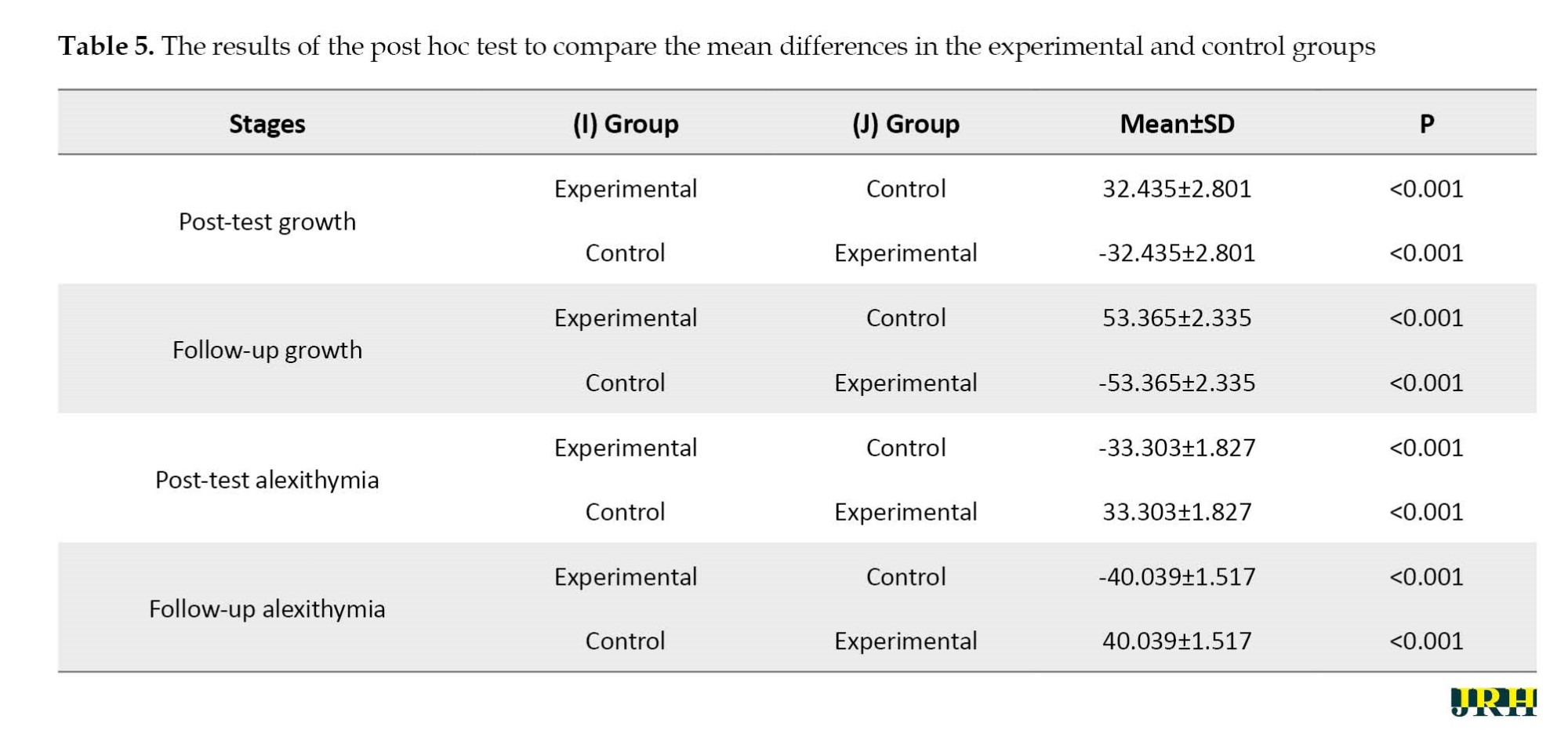

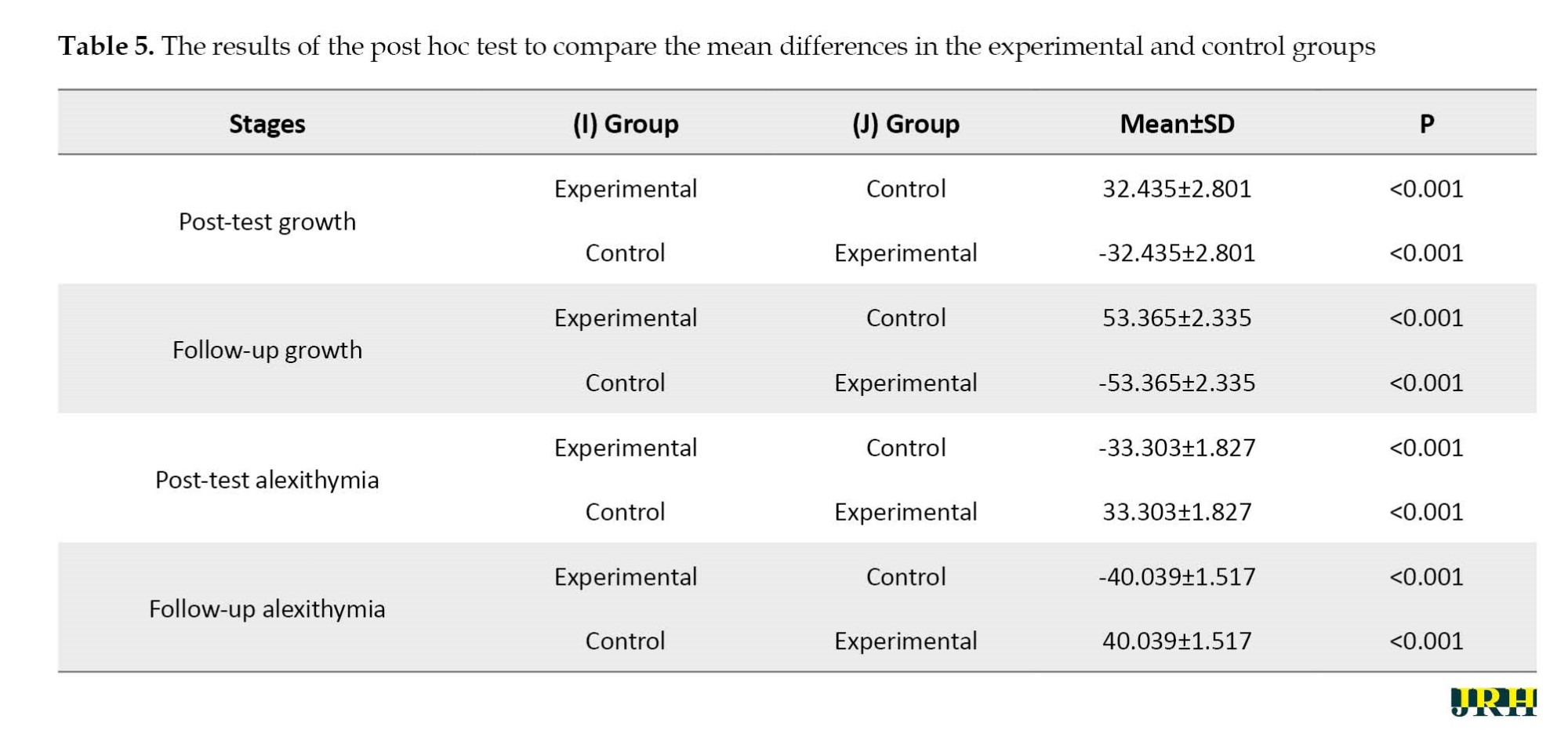

The result shows that the training was worthwhile. There is also a significant difference between love trauma syndrome at the post-test and follow-up stages (P<0.001). The results of the Bonferroni test for comparison between the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages show a significant difference in the posttraumatic growth score between the pre-test and post-test stages and between the pre-test and follow-up, which shows that training in the post-test and follow-up phase is better than the pre-test, demonstrating the effectiveness of the interventions. Also, there is a significant difference between the post-test and follow-up stages of posttraumatic growth (P<0.001), demonstrating that the average posttraumatic growth in the follow-up stage is increasing compared to the post-test and the symptoms after the completion of the course. However, they are still stable, this effectiveness has advanced to some extent, and the posttraumatic growth status of people with emotional failure improves over time (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of reality therapy on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth of women with emotional failure. The analysis showed that reality therapy had a significant effect on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth. The results support our finding that reality therapy alleviates alexithymia and improves PTG in women with emotional failure. Although the alexithymia and PTG variables were examined in this sample group for the first time using this approach, there was inconsistency among the studies. However, similar approaches have been examined in this sample group and with these variables, based on which the explanation of this section is drawn.

The results of Tavasoli et al. [23] and Karimi et al. [24] studies revealed a significant difference between the post-test scores of the experimental and control groups in terms of the components of attitudes toward the opposite sex (hostile and benevolent attitudes). Reality therapy enables these individuals to pay attention to their thoughts and feelings and to see and accept them without suppression and avoidance. Also, they believe that failure is an inseparable part of life and that human nature protects them against damages resulting from love failure [23]. In the reality therapy group, clients learned that cognition can be represented through controlling thoughts, feelings, and actions. The only way to achieve a successful identity for those who lose self-worth and efficiency through changing thoughts and behavior is to accept these unpleasant events and clearly understand their purposes. The clients perceive love failure as an inevitable part of these events, and they must stand up to it by accepting reality, using internal control, efficiency, and self-worth, not giving up, and not looking for guilt in their surroundings [24].

This result is similar to Zakeri et al. [29] and Sanagouye Moharer et al. [30], who reported that alexithymia could be reduced in women with emotional failure. A study by Sanagouye Moharer et al. [30] suggested that intervention approaches could reduce alexithymia in Iranian women undergoing couple therapy and Iranian adolescents. Reality therapy results suggest that those struggling to identify feelings, describe them, and think externally have lower alexithymia scores [31]. Tajdin et al. [31] compared the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy and reality therapy on alexithymia in clients. Their results showed that both therapeutic interventions effectively improved alexithymia in the experimental groups. Compassion-focused therapy and reality therapy were equally effective, and no significant difference existed. In this therapy, facing reality, accepting responsibility, recognizing basic needs, moral judgment about the rightness or wrongness of behavior, focusing on the here and now, internal control, and, as a result, the desire for a successful identity are emphasized [31]. According to the principles of this approach, people must learn whether or not others like them, and to feel valuable, they must show positive, pleasant behavior that conforms to accepted standards. To feel self-worth, they should learn to evaluate themselves when their behavior is wrong and be proud of themselves when their behavior is right [32].

Some studies have shown a positive correlation between PTG and resilience, resulting in improved social performance and overcoming problems in exposure to severe stress and risk factors [33]. PTG is also related to quality of life (QoL) and plays a protective role. However, lower levels of PTG hurt mood and QoL [34]. The benefits of experiencing PTG are vast. The benefits of traumatic experiences include making sense of loss, approaching wisdom, and enhancing purpose and meaning, which continue for 10 years after the traumatic event [35]. The factors associated with PTG range from intrapersonal to interpersonal and environmental. PTG occurs when adverse events are central to an individual’s self-identity. Of the 24-character strengths (e.g. gratitude, love, optimism), the strength of hope is best predicted by PTG. Furthermore, seeking social support, resilience, self-efficacy, and adaptive coping strategies are associated with the experiences of PTG [36]. Among young people, PTG was predicted by parenting rather than their intrapersonal assets [37], suggesting the environment’s role in helping an individual experience PTG. Then, based on reality therapy, the development of posttraumatic growth is possible [38]. This study shows that implementing five basic needs (survival, love and belonging, power, freedom, and fun) in choice theory and reality therapy may contribute to posttraumatic growth among youth [39]. In this approach, first, participants receiving reality therapy are required to identify the goal of their behavior (e.g. seeking relaxation after a stressful day of studying). Second, they are asked what they are doing (for example, playing). Third, they are guided on whether their behavior advances or hinders progress in reaching the primary goal. Finally, they are encouraged to look for more suitable and superior options to replace the current behavior to achieve the goal and plan to change the undesirable behavior [33].

One of the limitations of the present study was the study’s implementation among female students. Because the subjects of this study were single-sex, caution should be observed when generalizing the findings to other sexes. Therefore, according to the research results, it is suggested that similar research be conducted among people from different cultures. In this research, self-reporting tools (questionnaires) were used, which can cause fatigue in the subjects and decrease their accuracy and, to some extent, misinterpretation in answering the questions. Considering the implementation of the research among women with love failure and studying the research literature, which shows that most research is done on women with injuries, the authors suggested using male subjects in future research. Using questionnaires in this research, the authors recommended employing interview techniques and projective tests in future research to discover different dimensions of harm among the subjects. Evaluating the significance of the effectiveness of reality therapy on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth of women with emotional failure, the authors suggested teaching this therapeutic approach to psychology and counseling specialists.

Conclusion

The findings showed that reality therapy had a significant effect on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth of women with emotional failure. Therefore, reality therapy can be used for emotional failure syndromes. As it is clear from the results, there was a significant difference between the people who received reality therapy in the experimental group and those who did not receive any change in the control group in terms of research variables. Another critical point is the effects of reality therapy over time. As it is known, the effects of the interventions were also observed in the 3-month follow-up period of the people who were intervened with the reality therapy method. Based on this survey, people showed the results of changes in the reality therapy method during the follow-up phase. Therefore, the reality therapy method can have long-term clinical results on people with emotional breakdown syndromes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran Branch (Code: IR.IAU.REC. 1401.132).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mojgan Sepahmansour and Roya Kouchak Etezar; Methodology, data collection, data analysis, investigation and writing: Nina Sadeghi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Researchers are grateful to the counseling centers and those who participated in this study.

References

Love trauma syndrome is a set of severe signs and symptoms that appear after the breakup of a romantic relationship. It lasts long, disrupts a person’s performance in many fields (social, academic, and professional), and leads to maladaptive reactions [1]. Some symptoms have been shown to accompany emotional failure, including physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral difficulties [2]. When a relatively stable emotional relationship ends, very different feelings can arise. Although each person is unique, most people experience various stages of the phenomenon of loss [1]. An individual’s experiences after an emotional breakdown can include a wide range of emotions such as feelings of anger, sadness, depression, loneliness, anxiety and insomnia, physical symptoms, and ultimately, the breakdown of mutual trust and difficulty in re-establishing relationships with others [3]. Some believe that personality and emotional characteristics help understand romantic relationships, their quality, and positive and negative correlations with sentimental health and failure [4].

A review of the literature shows that one of the significant losses of people suffering from emotional failure is damage to the regulation and expression of emotions [5]. Alexithymia is a critical concept investigating issues related to emotion processing and regulation [6]. One underlying factor behind interpersonal problems is alexithymia [7]. A person with alexithymia has four distinct characteristics: Difficulty recognizing and describing emotions, difficulty distinguishing between emotions and physical stimuli, poor fantasy content, objective thinking, and weak introspection (extroverted thinking) [8]. The definition of alexithymia does not align with efficient emotion regulation, and researchers have shown that alexithymia is associated with ineffective emotion regulation [9]. For example, people with alexithymia are more likely to use suppression strategies and have less reappraisal than ordinary people. Among the two strategies mentioned, suppression strategies are more related to mental and physical health concerns and, therefore, are considered incompatible strategies to regulate emotions [10]. Ledermann et al. (2020) also showed that alexithymia was more common in people who had experienced trauma; therefore, paying attention to alexithymia and improving it among people suffering from emotional failure was necessary [11].

On the other hand, a traumatic experience such as an emotional failure can have a positive effect on a person, which is known as posttraumatic growth (PTG) [12]. Over the past decades, researchers have moved away from an exclusive focus on the negative aftermath following traumatic events. A growing body of studies document positive psychological changes after traumatic events [13, 14]. Tedeschi and Calhoun [15] referred to this phenomenon as PTG. It emphasizes the transformative quality of responding to traumatic events. The positive changes entail several domains, including perceived changes in self, a changed sense of relationship with others, and a changed philosophy of life. This concept refers to the positive personal and psychological changes after a severe and bitter event because the individual struggled against this stressful event, which has adaptive significance [15]. Breakup distress has generally been described in terms of stress and coping, suggesting a simple process to endure [16]. A recent alternative conceptualization called PTG has emerged, which interprets this distress as a more positive and growth-oriented process. PTG theory hypothesizes that traumatic experiences can promote “real life-transforming changes that go beyond illusion”[17].

A previously conducted meta-analysis of 26 studies demonstrated that 10% and 77.3% of participants experienced PTG [18]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of PTG identified that it is not associated with depression or anxiety [19]. Instead, it may coincide with depression and anxiety or exist in place of it. Thus, PTG is part of a complex system of outcomes related to trauma. If PTG can be enhanced after relationship dissolution, it will have important implications for understanding skills and relationship maintenance. Suppose people experience personal growth after a breakup. In that case, this growth can foster more successful relationships in the future and confer a developmental advantage to having multiple dating partners before long-term commitment [17].

Therefore, identifying effective interventions can help people, especially those who have experienced emotional failure. Many treatments have been recommended for people who go to a specialist because of their emotional breakdown syndrome, and these treatments fall into the two categories of psychotherapy and drug therapy [1]. Reality therapy is one treatment that increases resilience and emotional regulation strategies. The ability to accept reality, make ethical and responsible choices, build healthy relationships based on internal control, and live a prosperous and happy life. In reality therapy, symptoms and diseases are creative solutions for people to satisfy their needs, and the continuation of these methods. However, this therapy involves harm and suffering, showing their effect in fulfilling the needs [20]. Reality therapy is a method based on action. The therapist, along with the client, will create an acquirable program containing several positive stages, which will put him in the direction of satisfaction of the needs; the acronym WDEP (wants, direction, self-evaluation, planning) for describing methods executed in reality therapy [21].

In this approach, first, participants receiving reality therapy are asked to identify the goal of their behavior (e.g. seeking relaxation after a stressful study day). Second, they are asked what they are doing (for example, playing). Third, it educates them on whether their behavior advances or hinders progress toward the initial goal (e.g. playing may help relieve immediate stress, but excessive playing may interfere with study and health; as a result, it leads to more stress). Finally, it encouraged them to look for more suitable and superior options to replace the current behavior to achieve the goal and to plan to change the undesirable behavior (e.g. exercise instead of playing when feeling stressed) [22]. Tavasoli et al. investigated the effect of the group reality therapy approach on the symptoms of emotional failure and measured the overall performance of emotionally failed people. The results showed that group reality therapy reduced the symptoms of love failure and increased their overall performance score. Because group reality therapy increases a person’s responsibility and sense of control over his or her life, group reality therapy can be viewed as an effective method of reducing the symptoms of emotional failure and increasing an individual’s overall performance [23]. The results of another study revealed reality group therapy was effective in reducing the attitudes toward the opposite sex in female students with love trauma [24]. Thus, the authors conducted this study to determine the effectiveness of reality therapy on alexithymia and PTG in women with love failure.

Methods

This study was quasi-experimental research using a pre-test-post-test with a follow-up design. The statistical population of the present study comprised all the women with emotional failure experiences referred to Aramandish and Chaman clinics in Tehran City, Iran, during 2021 and 2022. The research involved the mentioned population, which met the inclusion criteria. A purposive sampling method was used to select the participants. The sample consisted of 20 women per group, calculated by G*Power software, version 3.1.9.7, with effect size=0.95, α=0.05, and test power=0.90 [24]. The participants in the research were divided into the experimental and control groups using a table of random numbers. In this method, even numbers were considered for the reality therapy group, and odd numbers were considered for the control group. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the experimental or control groups according to the odd or even number allocation. After dropping some samples, each group was composed of 15 participants (experimental and control groups). The inclusion criteria include the occurrence of non-marital emotional breakdown in the last six months (which was measured through a history), being 20 to 25 years old (a review of past research shows that emotional breakdown studies are often conducted at these ages), getting a score higher than 20 in the love trauma inventory, a score higher than 75 in the Toronto alexithymia scale, a score lower than 53 in the posttraumatic growth questionnaire, having at least a high school diploma (for reading and writing), and not suffering from psychological disorders such as depression, borderline personality, and obsession. Among the criteria for withdrawing from a research study are missing more than two sessions during the treatment period, getting involved in a new love relationship, or receiving treatment outside the study (self-administration or a psychiatrist’s prescription).

Because of gathering information from the Aramandish and Chaman clinics, we selected the desired applicants from there according to the inclusion criteria. As part of this research, the following actions were taken to respect the ethical concerns of the participants. At the beginning of the investigation, we collected informed consent from the participants after describing the research purposes. Before implementing the main treatment sessions, a meeting was held to explain the research, establish a good relationship, conduct a pre-test (Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS) and posttraumatic growth questionnaire), and collect information about the problems that confused them. In particular, a pre-test for alexithymia and posttraumatic growth was administered to the experimental group. Then Glasser’s [22] reality therapy intervention plan, whose validity has been confirmed by experts in this field, was applied to the experimental group in eight sessions of 90 minutes each, while the control group did not receive an intervention (Table 1).

The intervention sessions were implemented separately by each therapist within each center. Promptly after the completion of the interventions for the experimental group, the post-test of the research questionnaires was conducted for both groups. In the next step, two months after the post-test, the follow-up test was performed on both groups. Then, the results obtained in the post-test stage were analyzed by variance analysis with repeated measurements and covariance analysis using SPSS software, version 26. Before analyzing variance with repeated measurements, the results of Box’s M, Mauchly’s sphericity, and Levene’s tests were checked to comply with the statistical assumptions. According to the outcomes of Levene’s test, none of the variables were significant. Therefore, the assumption of the equality of variances between groups was respected, and the amount of error variance of dependent variables was equal in all groups.

Research tools

TAS

The alexithymia scale is a 20-item scale created by Bagby et al. [25] and evaluated alexithymia in three subscales: Difficulty in recognizing feelings (7 questions), difficulty in describing feelings (5 questions), and extraverted thinking (8 questions). Based on this scale, there are 5 possible answers: Totally disagree (1), disagree (2), neither disagree nor agree (3), agree (4), and totally agree (5). Bagbi et al. (1994) confirmed the self-validity of this tool and reported its reliability as 0.90. The validity of the Persian version of the TAS was found by the content validity ratio (CVR) as 0.88 and content validity index (CVI) as 0.82. Basharat [26] reported the validity of the entire scale in the Iranian sample was 0.71 and 0.83, and the scale’s validity was 0.85. For difficulty recognizing feelings, difficulty describing feelings, and extraverted thinking, the Cronbach α was used to calculate scale reliability coefficients of 0.83, 0.79, and 0.82, respectively. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.81

Posttraumatic growth inventory (PTGI)

Tedeschi and Calhoun designed the scale to evaluate the positive outcomes reported by people who experienced traumatic events [27]. This scale has 21 items with a 6-point Likert scale, which includes new possibilities, communication with others, personal power, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. The total scale scores of 105 and higher grades show higher posttraumatic growth. Tedeschi and Calhoun [27] reported that the posttraumatic growth scale has acceptable validity and reliability. In this study, ten experts confirmed the validity of the Persian version of this questionnaire (CVI=0.90, CVR=0.86). Heidarzadeh examined the reliability and validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire [28], confirming the 5-factor structure of the PTGI. The reported internal consistency was 0.87, and it ranged from 0.57 to 0.77 for the five dimensions. The test re-test correlation with a 30-day interval in 18 patients was 0.75. We also examined and confirmed the reliability of the questionnaire (α=0.92). In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.84.

Results

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis in SPSS software, version 26. According to Table 2, the majority of participants (23.3%) were in the age group of 20-21 years in the experimental group.

In the control group, both age groups of 20-21 and 22-23 (20%) years were equal. Most participants had bachelor’s degrees in the experimental group (30.0%) and in the control group (23.3%). Regarding occupation, 33.3% of people were employed in the experimental group, and 23.3% were employed in the control group. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed no significant difference between the groups in terms of age, education, and occupation (P>0.05 for all).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data. In addition, Levene’s test was used to check the homogeneity of variances. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the significance of the differences in the alexithymia and posttraumatic growth in women with love failure scores between the experimental and control groups. After comparing the post-test and follow-up scores to the pre-test results, there is a significant difference between alexithymia (F=31.014, P<0.0001) and posttraumatic growth (F=103.979, P<0.0001).

The researcher then used the ANCOVA method to compare the Mean±SD of the variables in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages, as shown in Table 3.

Using the Bonferroni test to compare the pre-test and post-test scores of love trauma syndrome and alexithymia, a significant difference was found between the pre-test and post-test scores (P<0.001) (Table 4).

The result shows that the training was worthwhile. There is also a significant difference between love trauma syndrome at the post-test and follow-up stages (P<0.001). The results of the Bonferroni test for comparison between the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages show a significant difference in the posttraumatic growth score between the pre-test and post-test stages and between the pre-test and follow-up, which shows that training in the post-test and follow-up phase is better than the pre-test, demonstrating the effectiveness of the interventions. Also, there is a significant difference between the post-test and follow-up stages of posttraumatic growth (P<0.001), demonstrating that the average posttraumatic growth in the follow-up stage is increasing compared to the post-test and the symptoms after the completion of the course. However, they are still stable, this effectiveness has advanced to some extent, and the posttraumatic growth status of people with emotional failure improves over time (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of reality therapy on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth of women with emotional failure. The analysis showed that reality therapy had a significant effect on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth. The results support our finding that reality therapy alleviates alexithymia and improves PTG in women with emotional failure. Although the alexithymia and PTG variables were examined in this sample group for the first time using this approach, there was inconsistency among the studies. However, similar approaches have been examined in this sample group and with these variables, based on which the explanation of this section is drawn.

The results of Tavasoli et al. [23] and Karimi et al. [24] studies revealed a significant difference between the post-test scores of the experimental and control groups in terms of the components of attitudes toward the opposite sex (hostile and benevolent attitudes). Reality therapy enables these individuals to pay attention to their thoughts and feelings and to see and accept them without suppression and avoidance. Also, they believe that failure is an inseparable part of life and that human nature protects them against damages resulting from love failure [23]. In the reality therapy group, clients learned that cognition can be represented through controlling thoughts, feelings, and actions. The only way to achieve a successful identity for those who lose self-worth and efficiency through changing thoughts and behavior is to accept these unpleasant events and clearly understand their purposes. The clients perceive love failure as an inevitable part of these events, and they must stand up to it by accepting reality, using internal control, efficiency, and self-worth, not giving up, and not looking for guilt in their surroundings [24].

This result is similar to Zakeri et al. [29] and Sanagouye Moharer et al. [30], who reported that alexithymia could be reduced in women with emotional failure. A study by Sanagouye Moharer et al. [30] suggested that intervention approaches could reduce alexithymia in Iranian women undergoing couple therapy and Iranian adolescents. Reality therapy results suggest that those struggling to identify feelings, describe them, and think externally have lower alexithymia scores [31]. Tajdin et al. [31] compared the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy and reality therapy on alexithymia in clients. Their results showed that both therapeutic interventions effectively improved alexithymia in the experimental groups. Compassion-focused therapy and reality therapy were equally effective, and no significant difference existed. In this therapy, facing reality, accepting responsibility, recognizing basic needs, moral judgment about the rightness or wrongness of behavior, focusing on the here and now, internal control, and, as a result, the desire for a successful identity are emphasized [31]. According to the principles of this approach, people must learn whether or not others like them, and to feel valuable, they must show positive, pleasant behavior that conforms to accepted standards. To feel self-worth, they should learn to evaluate themselves when their behavior is wrong and be proud of themselves when their behavior is right [32].

Some studies have shown a positive correlation between PTG and resilience, resulting in improved social performance and overcoming problems in exposure to severe stress and risk factors [33]. PTG is also related to quality of life (QoL) and plays a protective role. However, lower levels of PTG hurt mood and QoL [34]. The benefits of experiencing PTG are vast. The benefits of traumatic experiences include making sense of loss, approaching wisdom, and enhancing purpose and meaning, which continue for 10 years after the traumatic event [35]. The factors associated with PTG range from intrapersonal to interpersonal and environmental. PTG occurs when adverse events are central to an individual’s self-identity. Of the 24-character strengths (e.g. gratitude, love, optimism), the strength of hope is best predicted by PTG. Furthermore, seeking social support, resilience, self-efficacy, and adaptive coping strategies are associated with the experiences of PTG [36]. Among young people, PTG was predicted by parenting rather than their intrapersonal assets [37], suggesting the environment’s role in helping an individual experience PTG. Then, based on reality therapy, the development of posttraumatic growth is possible [38]. This study shows that implementing five basic needs (survival, love and belonging, power, freedom, and fun) in choice theory and reality therapy may contribute to posttraumatic growth among youth [39]. In this approach, first, participants receiving reality therapy are required to identify the goal of their behavior (e.g. seeking relaxation after a stressful day of studying). Second, they are asked what they are doing (for example, playing). Third, they are guided on whether their behavior advances or hinders progress in reaching the primary goal. Finally, they are encouraged to look for more suitable and superior options to replace the current behavior to achieve the goal and plan to change the undesirable behavior [33].

One of the limitations of the present study was the study’s implementation among female students. Because the subjects of this study were single-sex, caution should be observed when generalizing the findings to other sexes. Therefore, according to the research results, it is suggested that similar research be conducted among people from different cultures. In this research, self-reporting tools (questionnaires) were used, which can cause fatigue in the subjects and decrease their accuracy and, to some extent, misinterpretation in answering the questions. Considering the implementation of the research among women with love failure and studying the research literature, which shows that most research is done on women with injuries, the authors suggested using male subjects in future research. Using questionnaires in this research, the authors recommended employing interview techniques and projective tests in future research to discover different dimensions of harm among the subjects. Evaluating the significance of the effectiveness of reality therapy on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth of women with emotional failure, the authors suggested teaching this therapeutic approach to psychology and counseling specialists.

Conclusion

The findings showed that reality therapy had a significant effect on alexithymia and posttraumatic growth of women with emotional failure. Therefore, reality therapy can be used for emotional failure syndromes. As it is clear from the results, there was a significant difference between the people who received reality therapy in the experimental group and those who did not receive any change in the control group in terms of research variables. Another critical point is the effects of reality therapy over time. As it is known, the effects of the interventions were also observed in the 3-month follow-up period of the people who were intervened with the reality therapy method. Based on this survey, people showed the results of changes in the reality therapy method during the follow-up phase. Therefore, the reality therapy method can have long-term clinical results on people with emotional breakdown syndromes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran Branch (Code: IR.IAU.REC. 1401.132).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mojgan Sepahmansour and Roya Kouchak Etezar; Methodology, data collection, data analysis, investigation and writing: Nina Sadeghi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Researchers are grateful to the counseling centers and those who participated in this study.

References

- Rosse RB. The love trauma syndrome: Free yourself from the pain of a broken heart. London: Hachette UK; 2007. [Link]

- Bansal V, Kansal MM, Rowin J. Broken heart syndrome in myasthenia gravis. Muscle & Nerve. 2011; 44(6):990-3. [DOI:10.1002/mus.22220] [PMID]

- Etemadnia M, Sh S, Khalatbari J, Sh A. [Predicting Love Trauma Syndrome in college students based on personality traits, early maladaptive schemas, and spiritual health (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2021; 27(3):318-35. [Link]

- Gómez-López M, Viejo C, Ortega-Ruiz R. Well-being and romantic relationships: A systematic review in adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2415. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16132415] [PMID]

- Vajdian M, Arefi M, Manshai Gh. [The effect of adolescent-based mindfulness training on the resilience and emotional regulation of girls with affective failure (Persian)]. Cognitive Analytical Psychology Quarterly. 2019; 11(43):55-68. [DOI: 10.22038/mjms.2020.16178]

- Maroti D, Lilliengren P, Bileviciute-Ljungar I. The relationship between alexithymia and emotional awareness: A meta-analytic review of the correlation between TAS-20 and LEAS. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018; 9:453. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00453] [PMID]

- da Silva AN, Vasco AB, Watson JC. Alexithymia and emotional processing: A mediation model. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017; 73(9):1196-205. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22422] [PMID]

- Karukivi M, Saarijärvi S. Development of alexithymic personality features. World Journal of Psychiatry. 2014; 4(4):91-102. [DOI:10.5498/wjp.v4.i4.91] [PMID]

- Panasiti MS, Ponsi G, Violani C. Emotions, alexithymia, and emotion regulation in patients with psoriasis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:836. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00836] [PMID]

- Zhang H, Fan Q, Sun Y, Qiu J, Song L. A study of the characteristics of alexithymia and emotion regulation in patients with depression. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 2017; 29(2):95-103. [PMID]

- Ledermann K, von Känel R, Barth J, Schnyder U, Znoj H, Schmid JP, et al. Myocardial infarction-induced acute stress and post-traumatic stress symptoms: The moderating role of an alexithymia trait-difficulties identifying feelings. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2020; 11(1):1804119. [DOI:10.1080/20008198.2020.1804119] [PMID]

- Chen J, Zhou X, Zeng M, Wu X. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and post-traumatic growth: Evidence from a longitudinal study following an earthquake disaster. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6):e0127241. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0127241] [PMID]

- McElheran M, Briscoe-Smith A, Khaylis A, Westrup D, Hayward C, Gore-Felton C. A conceptual model of post-traumatic growth among children and adolescents in the aftermath of sexual abuse. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2012; 25(1):73-82. [DOI:10.1080/09515070.2012.665225]

- Shigemoto Y, Poyrazli S. Factors related to posttraumatic growth in US and Japanese college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013; 5(2):128-34. [DOI:10.1037/a0026647]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma & transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [DOI:10.4135/9781483326931]

- Spilkin SE. The role of the nervous system in post-traumatic growth: A grounded theory study [PhD dissertation]. Chicago: The Chicago School of Professional Psychology; 2017. [Link]

- Owenz M, Fowers BJ. Perceived post-traumatic growth may not reflect actual positive change: A short-term prospective study of relationship dissolution. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2019; 36(10):3098-116. [DOI:10.1177/0265407518811662]

- Wu X, Kaminga AC, Dai W, Deng J, Wang Z, Pan X, et al. The prevalence of moderate-to-high posttraumatic growth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019; 243:408-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.023] [PMID]

- Long LJ, Phillips CA, Glover N, Richardson AL, D’Souza JM, Cunningham-Erdogdu P, et al. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021; 22:3703–28. [DOI:10.1007/s10902-021-00370-9]

- Joyce LM, DiGiangi H, Norman S. Trauma treatment a choice theory/reality therapy perspective. International Journal of Choice Theory and Reality Therapy. 2021; 40(2):15-21.[Link]

- Farnoodian P. The effectiveness of group reality therapy on mental health and self-esteem of students.International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences (IJMRHS). 2016; 5(9):18-24. [Link]

- Glasser W. Counseling with choice theory: The new reality therapy. New York: Harper Collins; 2001. [Link]

- Tavasoli Z, Aghamohammadin Sherbaf HR, Sepehri Shamloo Z, Shahsavari M. [Effectiveness of group Reality Therapy on love trauma syndrome and overall function of people who failed emotionally (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2018; 12(1):83-102. [Link]

- Karimi S, Jahan J, Pourmohammad Ghouchani K, Azadi F, Alizadeh M, RanjbarSudejani Y. [Effectiveness of reality group therapy on attitudes to the opposite sex in female students with love trauma syndrome (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Studies. 2020; 16(1):141-56. [Link]

- Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ. The twentyitem Toronto Alexithymia Scale--I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994; 38(1):23-32. [DOI:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1] [PMID]

- Besharat MA. Reliability and factorial validity of a Farsi version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale with a sample of Iranian students. Psychological Reports. 2007; 1101(1):209-20.[DOI:10.2466/PR0.101.5.209-220] [PMID]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996; 9(3):455-71. [DOI:10.1007/BF02103658] [PMID]

- Heidarzadeh M, Rassouli M, Mohammadi Shahbolaghi F, Alavi Majd H, Karam A, Mirzaee H, et al. Posttraumatic growth and its dimensions in patients with cancer. Middle East Journal of Cancer. 2014; 5(1):23-9. [Link]

- Zakeri F, Tosi MS, Nejat H. [Investigating the role of Self-Compassion moderator on the relationship between Alexithymia and Couple Burnout in incompatible women (Persian)]. Psychotherapy and Counseling, Education. 2019; 29(8):52-64. [Link]

- Sanagouye Moharer G, Shirazi M, Kia S, Karami Mohajeri Z. [The effect of compassion focused training on hope, life satisfaction and alexithymia of delinquent female adolescents (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2020; 8(3):46-56. [Link]

- Tajdin A, AleYasin A, Heydari H, Davodi H. [Comparison on the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy and reality therapy on alexithymia among male prisoner clients (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Science. 2021; 19(95):1519-32. [Link]

- Haskins NH, Appling B. Relational‐cultural theory and reality therapy: A culturally responsive integrative framework. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2017; 95(1):87-99. [DOI:10.1002/jcad.12120]

- Yao YW, Chen PR, Chiang-shan RL, Hare TA, Li S, Zhang JT, et al. Combined reality therapy and mindfulness meditation decrease intertemporal decisional impulsivity in young adults with Internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017; 68:210-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.038]

- Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala KL, Back AL, Wolfe J. Promoting resilience among parents and caregivers of children with cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013; 16(6):645-52. [DOI:10.1089/jpm.2012.0494] [PMID]

- Cormio C, Romito F, Viscanti G, Turaccio M, Lorusso V, Mattioli V. Psychological well-being and posttraumatic growth in caregivers of cancer patients. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014; 5:1342. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01342] [PMID]

- Powell T, Gilson R, and Collin C. TBI 13 years on: Factors associated with post-traumatic growth. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2012; 34(17):1461-7. [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2011.644384] [PMID]

- O’Donovan R, Burke J. Factors associated with post-traumatic growth in healthcare professionals: A systematic review of the literature. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2022; 10(12):2524. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10122524] [PMID]

- Koutná V, Jelínek M, Blatný M, Kepák T. Predictors of posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in childhood cancer survivors. Cancers (Basel). 2017; 9(3):26. [DOI:10.3390/cancers9030026] [PMID]

- Kim YJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a mediator between trauma exposure and comorbid mental health conditions in North Korean refugee youth resettled in South Korea. J Interpers Violence. 2016; 31(3):425-43. [DOI: 10.1177/0886260514555864] [PMID]

- Supeni I, Jusoh AJ. Psychological aspects of the Choice Theory Reality Therapy (CTRT) approach on sexual misconduct: Cases in women’s shelters. International Journal of Education, Information Technology, and Others. 2021; 4(4):708-22.[Link]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Health Education

Received: 2023/03/10 | Accepted: 2023/09/5 | Published: 2024/05/1

Received: 2023/03/10 | Accepted: 2023/09/5 | Published: 2024/05/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |