Volume 14, Issue 2 (Mar & Apr 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(2): 177-188 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kosari F, Sabahi P, Makvand Hosseini S. Comparative Effects of Parent Management Training Combined With ACT and Mindful Parenting on Parent-child Relationship. J Research Health 2024; 14 (2) :177-188

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2351-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2351-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Mahdishahr Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran. ,P_sabahi@semnan.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychology, Mahdishahr Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Mahdishahr Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, Mahdishahr Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 767 kb]

(953 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3646 Views)

Full-Text: (2251 Views)

Introduction

The formation of an individual’s relationship with oneself and others is significantly influenced by their experiences during infancy and childhood in the context of their primary caregiver. These early experiences have a subsequent impact on their relationships with both themselves and others. Parent-child relationship plays a fundamental role because it serves as the child’s initial introduction to the realm of communication and holds immense importance in fostering feelings of security and love [1]. Children depend on the reciprocal influence exerted by their parents because they keenly observe their behaviors and engage in interactions with them. These interactions serve as a foundation for children to develop an understanding of the social dynamics that encompass their lives. This mutual influence between parents and children assumes a pivotal role in shaping a child’s overall growth and development. Hence, it can be asserted that the parent-child relationship represents a dynamic amalgamation of distinctive behaviors, emotions, and individual expectations [2]. The parent-child relationship encompasses various modes of communication, encompassing verbal exchanges, visual observations, auditory perceptions, mutual understanding, accessibility, and other means of fostering interaction. It is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that is influenced by several key factors, including parental attitudes, levels of acceptance, behavior management strategies, social competence, self-esteem, parental knowledge and skills, self-assurance, and parenting beliefs regarding child-rearing [3]. These factors collectively shape the quality of parent-child relationships and maternal emotional caregiving while creating an environment characterized by minimal conflict [4]. The parent-child relationship can significantly influence children’s mental health. Numerous studies have provided evidence for the significant impact of the quality of parent-child relationships, particularly the mother-child relationship, on children’s psychological well-being, resulting in long-lasting effects [5, 6].

Undoubtedly, during childhood, parents and the parent-child relationship hold a prominent position as significant influencers in the development of social and psychological dimensions. The quality of parent-child relationships and the overall family environment serve as a fundamental factor that shapes the children’s well-being [7]. Conversely, obstacles encountered in parent-child interaction pose potential risks to a child’s developmental trajectory. Enhancing the quality of parent-child interaction has been associated with decreasing behavioral issues among children, promoting prosocial behaviors, cultivating effective parenting skills, such as firm discipline and structure, as well as alleviatingparental stress and tension [8].

Considering the paramount significance of the psychological well-being of parents and children, along with the crucial role of maintaining a wholesome parent-child relationship that fosters family well-being, it becomes imperative to address the pivotal and influential factors embedded within parenting practices. Consequently, a multitude of educational programs and interventions have been meticulously developed and executed, seeking to educate and empower parents. Among these programs, parent management training (PMT) emerges as one of the prevailing and efficacious approaches to parenting education, consistently substantiated by empirical evidence [9]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that such comprehensive training can effectively enhance the regulation of parents’ emotions, foster greater compassion towards both the parent and the child, and mitigate the child’s behavioral difficulties [10]. Moreover, this program has a significant impact on reducing aggressive parenting styles and enhancing parental self-regulation [11]. By enhancing parenting skills and diminishing negative emotions while cultivating positive emotions among parents [12], this intervention holds promise to foster a healthier parent-child relationship. In recent years, a notable intervention that has garnered significant attention is the integrated approach combining PMT and mindful parenting. This integrated program emphasizes active listening, and non-judgmental acceptance of both oneself and the child, and places a strong emphasis on mindfulness and non-judgmental comprehension of the child’s challenges, while consciously avoiding automatic parenting patterns. Furthermore, the combined program aims to break the intergenerational cycle of problems by addressing the parents’ schemas [13]. In addition, to enhance parenting skills, a recent intervention that has gained attention is mindful parenting, which focuses on promoting mental health and preventing psychological and behavioral disorders in children [14]. This approach incorporates mindfulness practices into the realm of parenting. Through this intervention, parents undergo training to redirect their attention from problematic child behaviors, damages, and parental distress toward the present moment and the unfolding experience in an authentic manner [15]. Research has demonstrated that mindful parenting has yielded positive outcomes in the parent-child relationship and has reduced parental tension in mothers. It has also been associated with a decrease in children’s behavioral problems [16].

An additional noteworthy intervention program is the combination of acceptance commitment therapy (ACT) with PMT. This program aims to assist parents in recognizing and accepting their emotions and concerns, aligning their actions with their values during challenging interactions with their child, and identifying and eliminating ineffective behaviors. Furthermore, it emphasizes the cultivation of mindfulness and non-judgmental observation while seeking to reduce experiential avoidance through compassion and kindness, ultimately reducing self-criticism among parents during difficult parenting moments [17]. Consequently, it promotes parents’ persistence in addressing crucial issues, thereby enhancing the significance of the parent-child relationship [18]. This approach has demonstrated efficacy in reducing parental stress and depression, enhancing quality of life, and improving child performance [19]. Additionally, this intervention fosters parental acceptance and enhances adaptive modes of interaction with the child.

Research studies have indicated that the combined utilization of these two programs has demonstrated greater effectiveness compared to non-combined programs [18, 20, 21]. However, it is essential to note that a lack of empirical evidence directly compares the outcomes of these combined programs. Both ACT and mindfulness-based interventions share several similarities and fall under the umbrella of third-wave treatments [22]. These therapeutic approaches aim to explore and address the parent’s cognitive processes, emotional regulation, and overall well-being.

In the realm of education and child development, the involvement of parents holds paramount importance. They serve as vital guides and creators of nurturing environments for their children. While educational institutions play a significant role in shaping students’ academic and social skills, the parent-child relationship, effective communication, and parental engagement have emerged as crucial elements in fostering a child’s learning and overall development. Consequently, recognizing the significance of cultivating strong parent-child connections and promoting effective communication becomes imperative for achieving optimal educational outcomes for both the child and the parent. Furthermore, parental engagement not only enhances their comprehension but also serves as a driving force for academic achievement and the acquisition of essential life skills. Thus, it is crucial to acknowledge the indispensable role of parents in their children’s education and to emphasize the importance of fostering effective communication to facilitate growth and success in both academic and personal domains.

The objective of this research was to determine the relative efficacy of two interventions in enhancing the parent-child relationship. Specifically, the study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of a combined program consisting of ACT-based parenting and PMT with a combined program comprising mindful parenting and PMT. The primary focus was to assess the impact of these interventions on the enhancement of the parent-child relationship.

Methods

The study used a quasi-experimental design, specifically employing a pre-test and post-test method, with a three-month follow-up period. To enhance the validity of the results, a control group was incorporated. The statistical population comprised all mothers of preschool children in Semnan City, Iran in 2022.

One method to estimate sample size in quasi-experimental designs is the use of the Equation 1:

1. N=(2×(Zα+Zβ)/Δ)2

In this formula, n represents the number of samples in each group. Zα and Zβ represent the critical values from the normal distribution for the significance level (α) and statistical power (1-β), respectively. Δ represents the meaningful difference between the two groups. For example, to determine sample size in each group with a significance level of 0.05, statistical power of 0.8, and assuming a meaningful difference between the groups of 5 units, we can extract the corresponding values of Zα and Zβ from the relevant table and substitute them into the formula to calculate the sample size [23]. If we want to estimate the minimum sample size, we can use the following values:

Zα=1.96 (for a significance level of 0.05)

Zβ=0.84 (for a statistical power of 0.8)

Consequently, by substituting these values into the formula, we can determine the minimum sample size required in each group to ensure a minimum of 12 to 15 participants in each group.

Using convenience sampling, 36 mothers were selected and were then randomly assigned to three groups, two experimental groups and one control group. Random assignment was achieved through a lottery-based method without replacement. Twelve mothers received training based on the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, while another twelve mothers were educated using the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT. These training sessions were conducted over eight weeks, with two-hour sessions held weekly. The control group was placed on a waiting list.

The study implemented specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the meticulous selection of participants. The inclusion criteria included several essential factors. First, participants were required to have a child aged between 5 and 7 years. They were expected to reside with a spouse and show a willingness to participate in the parenting sessions. Mothers were expected to hold a minimum educational qualification of at least a high school diploma, showing a level of educational attainment. In contrast, the study also defined exclusion criteria to identify individuals who did not meet the desired eligibility. The presence of psychological disorders and the usage of psychiatric medications by either the mother or the child were evaluated through psychological interviews conducted by the researcher. Participants displaying these conditions were excluded from the study. Also, chronic diseases affecting either the mother or the child were considered grounds for exclusion due to their potential to confound the study results. Other exclusion criteria included absenteeism from over two training sessions, marital separation or divorce, and a diminishing tendency to actively engage in the research. It is crucial to ensure the commitment and involvement of participants throughout the study. Finally, individuals simultaneously receiving psychological services and participating in the study were also excluded because this dual involvement can introduce additional variables that may influence the outcomes.

By carefully having these inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study was conducted to create a more homogeneous and appropriate participant group for the research, ensuring the integrity and validity of the results.

Measures

Pianta parent-child relationship scale (PCRS): Pianta parent-child relationship scale (PCRS), developed by Pianta in 1992 [24], is a 33-item instrument utilized to assess various aspects of the parent-child relationship. It encompasses dimensions, such as parent-child dependency, perceived conflicts, and the degree of closeness. The scale comprises three sub-scales, conflict, closeness, and dependency. The conflict sub-scale includes the following questions, 2, 4, 7, 21, 23, 24, 12, 14, 17, 19, 25, 26, 32, 33, 27, 28, and 31. Questions related to closeness are numbered as 6, 8, 10, 13, 1, 3, 5, 16, 29, and 30. Finally, the dependency sub-scale consists of questions 22, 18, 11, 15, 9, and 20. In addition, a measure of positive relationship was obtained by combining responses from all items. A 5-point Likert scale was employed to rate the questionnaire, where higher scores indicate a more positive parent-child relationship. Driscoll and Pianta reported the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the conflict, closeness, dependency sub-scales, and the total positive relationship as 0.75, 0.74, 0.69, and 0.80, respectively [24]. These coefficients indicate the internal consistency and reliability of the scale. The PCRS serves as a comprehensive tool to assess various dimensions of the parent-child relationship and has demonstrated satisfactory reliability through the reported Cronbach’s α coefficients. In the Iranian context, the reliability of the sub-scales of the PCRS, namely conflict, closeness, and dependency, was reported to be 0.68, 0.71, and 0.73, respectively, using Cronbach’s α coefficient. Additionally, the sub-scale demonstrated a total positive relationship with a total reliability of 0.78. These results indicate satisfactory internal consistency and reliability of the PCRS sub-scales in assessing the parent-child relationship within the Iranian population [25]. Furthermore, in the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.79, indicating good reliability for the questionnaire.

Research implementation process

Initially, the potential participants were invited to attend a briefing session where the research objectives and session procedures were thoroughly explained. During this meeting, ethical considerations, including the principles of confidentiality and the protection of parents’ information, were emphasized. Subsequently, the research questionnaire was distributed to the parents for sampling purposes, and eligible participants were selected as the study sample. Random assignment was employed to allocate mothers into the control and experimental groups, each consisting of 12 members. The control group was placed on a waiting list while the training sessions commenced. The training program spanned two months, and upon completion, a post-test assessment was administered to all three groups. Furthermore, a three-month follow-up evaluation was conducted to assess the long-term effects.

Twelve mothers in one experimental group underwent the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, which consisted of eight weekly sessions, with each session lasting two hours. Bögels and Restifo developed the mindful parenting program in 2014 [26], and the PMT program was based on Sanders’ model [27] as the following:

First session: Explaining automatic parenting, fight-flight, and freeze reactions, as well as positive interaction training.

Second session: Adopting a perspective of seeing a child with a beginner’s mind and conducting an exploration of their body, while also emphasizing the importance of employing the rationale behind physical affection.

Third session: Cultivating self-kindness and integration of Yoga practices, and guiding effective verbal communication and empathetic engagement with children.

Fourth session: Emphasizing the significance of responding to rather than reacting impulsively to a child’s behavior, along with teaching methods for delivering appropriate praise.

Fifth session: Explaining ineffective inter-generational models and training techniques for effectively giving instructions and setting boundaries for children.

Sixth session: Providing instruction on how to rebuild the parent-child relationship and implementing logical consequences for behavior.

Seventh session: Mindful approach to determining rules and regulations, as well as utilizing behavior chart training to foster positive behavioral patterns.

Eighth session: Summarizing the principles of mindful parenting and highlighting the importance of avoiding avoidance and deprivation in the parent-child relationship.

Twelve mothers in one experimental group underwent the combination of ACT-based parenting with PMT which consisted of eight weekly sessions, with each session lasting two hours. The ACT-based parenting was derived from “the joy of parenting: An acceptance and commitment therapy guide to effective parenting in the early years” by Murrell and Coyne in 2009 [28], and PMT was based on Sanders’ model [29] as the following:

First session: Parents’ familiarity with their psychological processes and the potential impact of reactive parenting on both short-term and long-term outcomes. Implementation of positive interaction training.

Second session: Exploring parental values and utilizing the metaphor of the “islands of competence” to enhance understanding. Presenting the rationale behind the importance of physical affection.

Third session: Conducting a functional analysis of challenging situations involving children and providing problem-solving strategies was discussed in this section. Additionally, it offers guidance on effective verbal communication and empathetic engagement with children.

Forth session: Providing mindfulness training to cultivate the ability to acknowledge and experience various emotions without avoidance. Teaching effective strategies for praising and giving instructions to children.

Fifth session: Planning strategies to manage tantrums and adjusting consequences are explored in this section. It further explains the concept of logical consequences for behavior and emphasizes the importance of their implementation.

Sixth session: This session addresses the importance of recognizing parenting mistakes and fostering the skill of self-reflection. It guides implementing behavior charts as a tool to monitor and reinforce daily behaviors.

Seventh session: Comparing oneself to the ideal parent and practicing self-care. Strategies for addressing behavioral problems and teaching avoidance.

Eighth session: Fostering commitment in mothers to adhere to the established plan is the focus of this part. It also provides instruction on teaching the concept of deprivation and its underlying principles.

It is noteworthy that the researcher has completed a comprehensive training program on PMT and parenting skills based on ACT, in addition to mindful parenting, at esteemed institutions under the guidance of highly qualified and experienced professional instructors.

The data analysis phase involved utilizing SPSS software, version 23 and applying multivariate covariance analysis.

Results

The Mean±SD in the mindful parenting group was 36.58±3.02 for mothers and 5.75±0.452 for children. In contrast, the ACT-based parenting group had a Mean±SD age of 35.75±3.10 for mothers and 6.50±0.52 for children. The Mean±SD age of the control group was 35.08±3.98 for mothers and 5.42±0.51 for children. Regarding the education level of mothers in the mindful parenting group, the frequency and percentage distribution were Bachelor’s degree 7(58.3%) and master’s degree 5(41.7%). In the ACT-based parenting group, the frequency and percentage distribution were 7 (58.3%) for a Bachelor’s degree and 5(41.7%) and for a master’s degree. In the control group, the frequency and percentage distributions were 3(0.25%) for diplomas, 7(58.3%) for Bachelor’s degrees, and 1(8.3%) each for Master’s and PhD degrees. The distribution of working mothers and housewives in the mindful parenting group was 8(66.5%) and 4(33.3%), respectively. In the ACT-based parenting group, 9(75%) were working mothers and 3(25%) were housewives. Similarly, in the control group, 5(41.7%) were working mothers and 7(58.3%) were housewives.

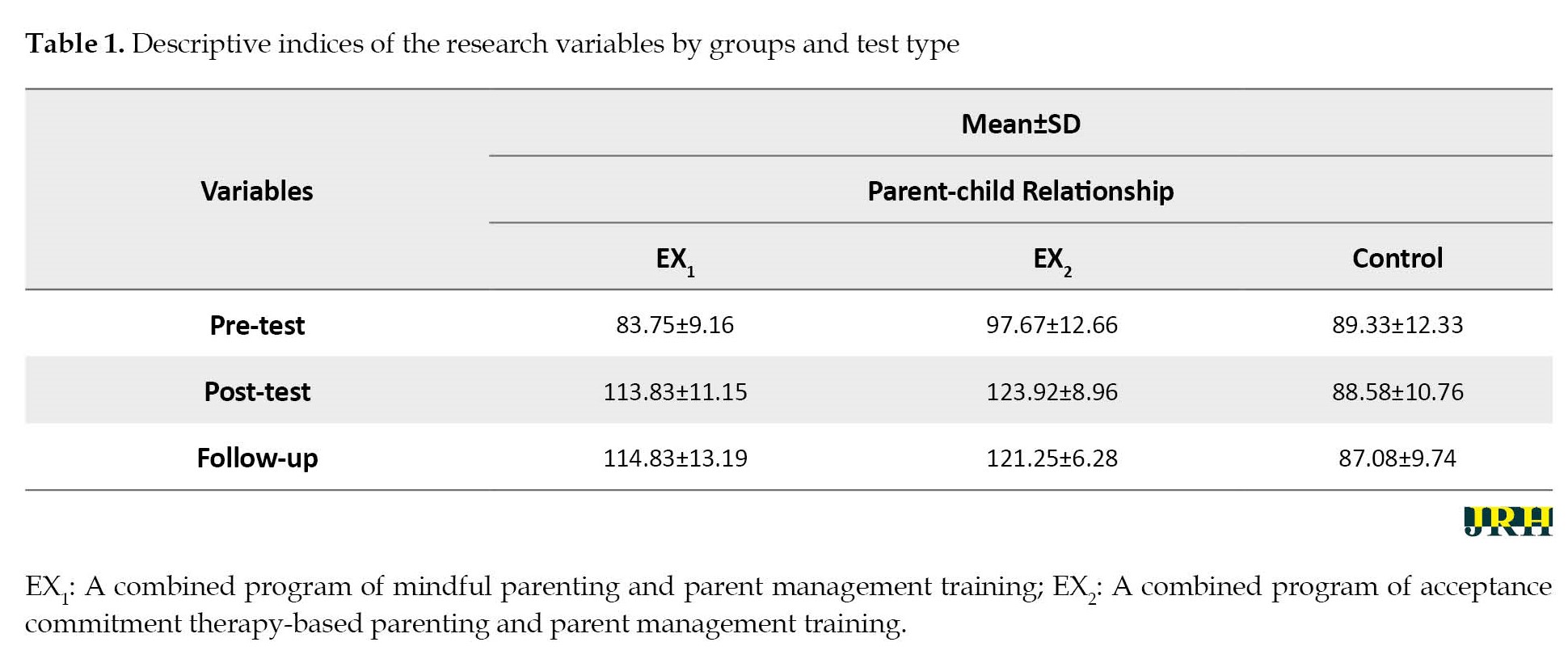

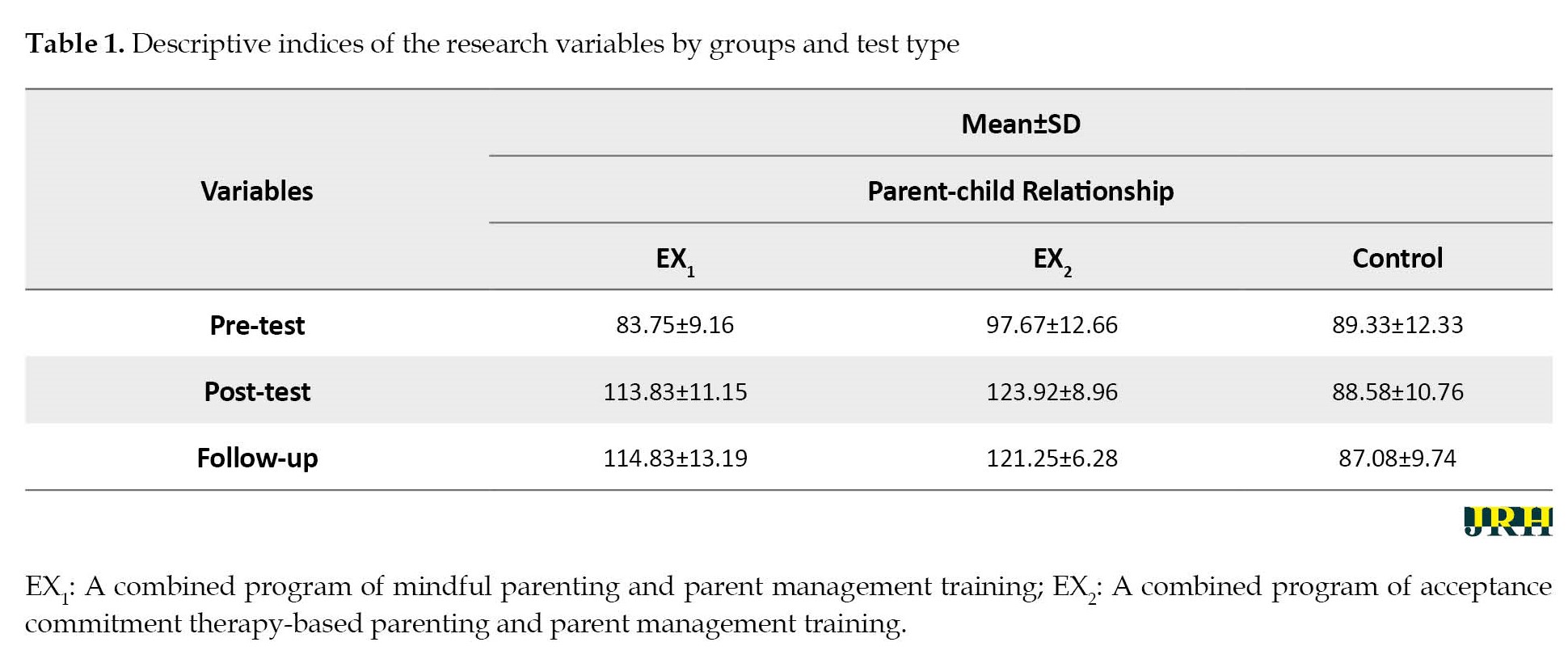

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD values of the control and experimental groups in three phases, pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

The results showed that the mean score of the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT increased in the post-test and follow-up stages. Similarly, in the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT, the mean score increased in the post-test but showed a decreasing trend in the follow-up stage. To analyze the data and control the pre-test scores, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was employed, using the pre-test scores of the research variables as covariance variables.

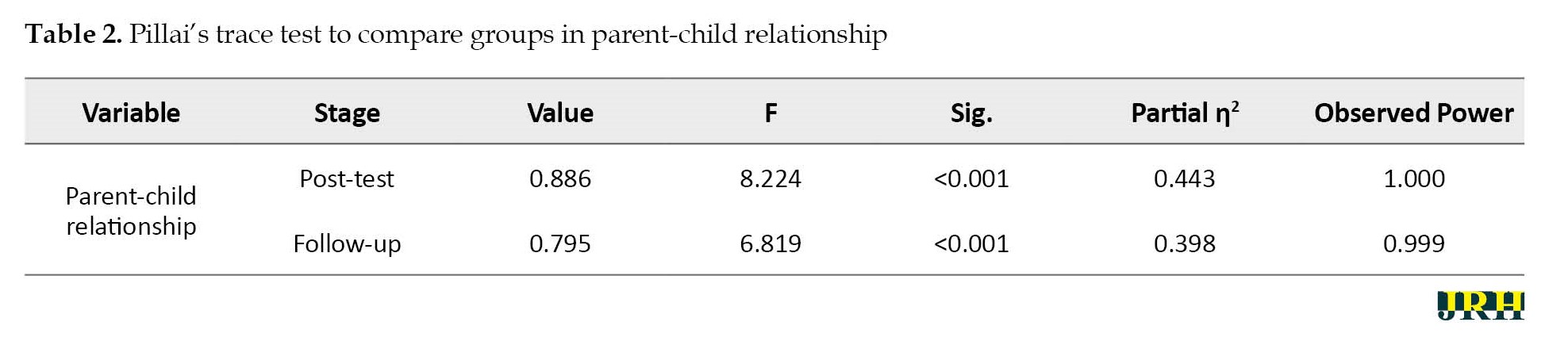

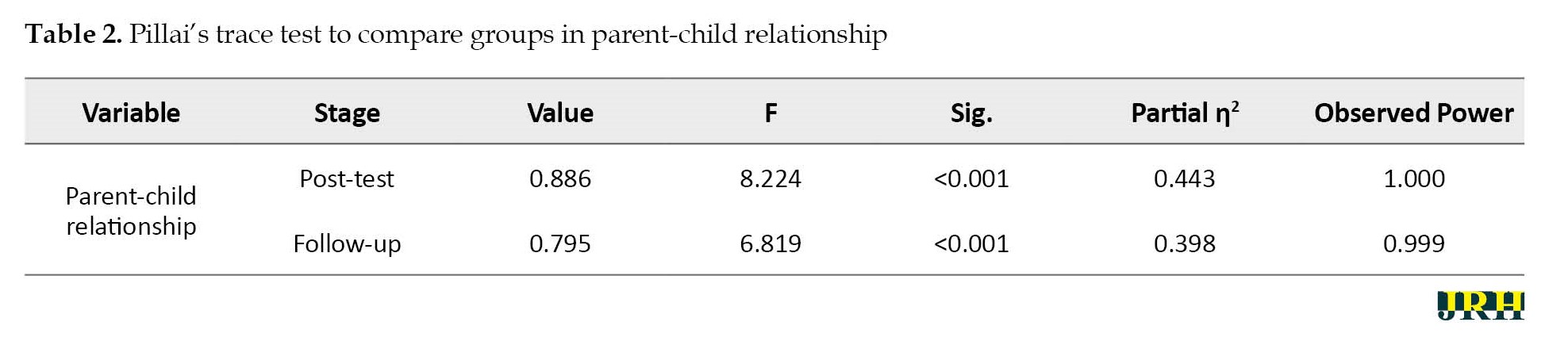

Before conducting MANCOVA, the necessary assumptions were examined. The normality of data in each group was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The significance level of all dependent variables in both the control and experimental groups was P>0.05, indicating the normality of the data. Additionally, the assumption of equivalence of covariance matrices was evaluated using Box’s M test, which showed no significant deviations in the post-test (Box’s M: 13.060, F=0.943, P=0.502) and follow-up (Box’s M: 17.818, F=1.28, P=0.219) stages. Levene’s test was employed to examine the assumption of homogeneity of variances for the dependent variable, and it was satisfied in the post-test, follow-up, and three sub-scales (P≥0.05). However, the results of Butler’s Sphericity test did not support this assumption (P=0.007). Therefore, more stringent tests, such as Pillai’s Trace were utilized.

Based on the F value and its significance level presented in Table 2, it can be concluded that a significant difference is observed between the research groups in the dependent variables, even after eliminating the effect of the pre-test.

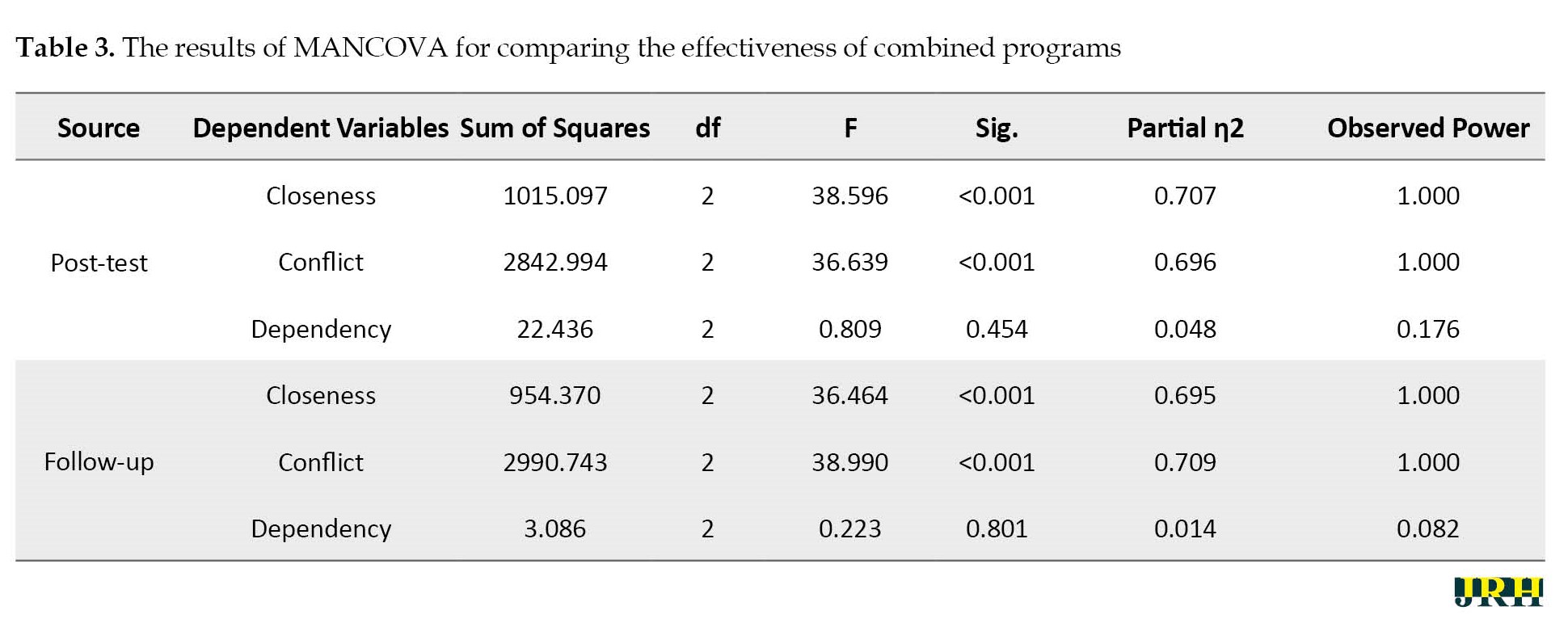

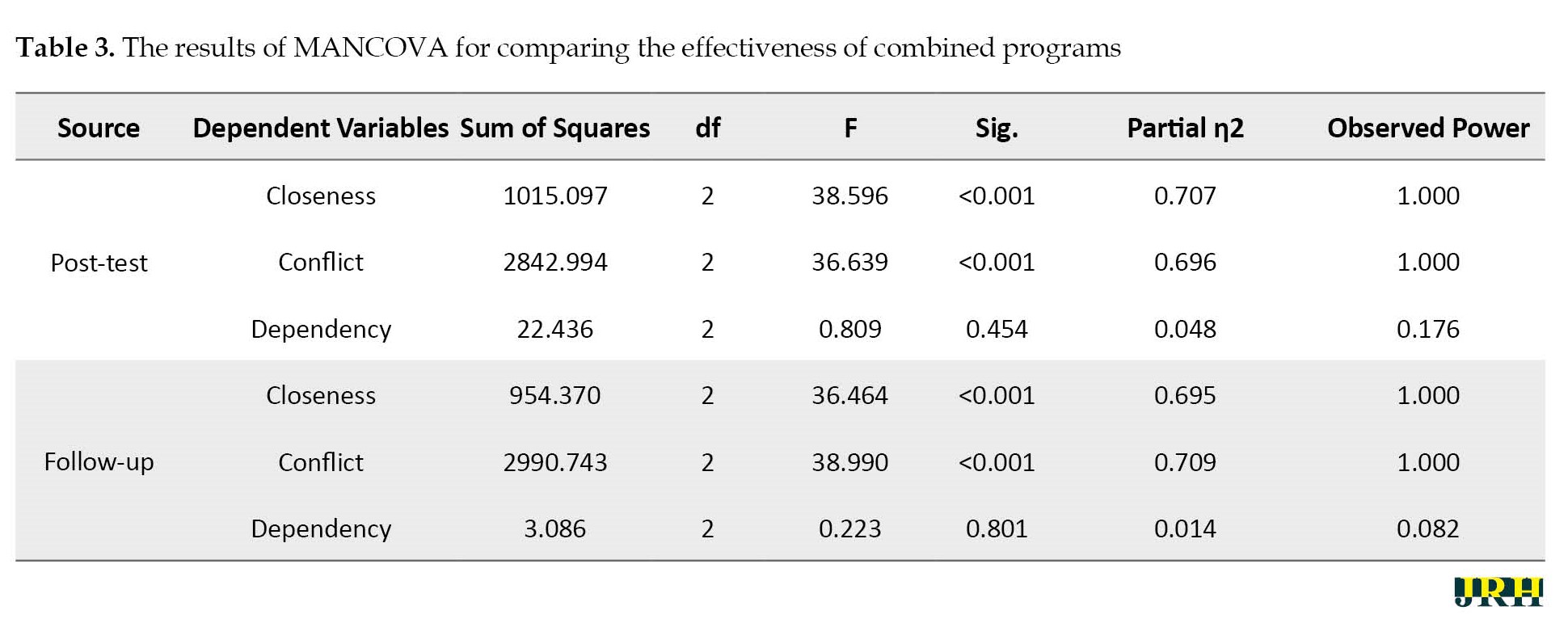

Table 3 presents the results of the MANCOVA analysis, demonstrating a significant difference among the three groups (combination of ACT-based parenting and PMT, combination of mindful parenting and PMT, and control) in all closeness, conflict, and variables except for dependency.

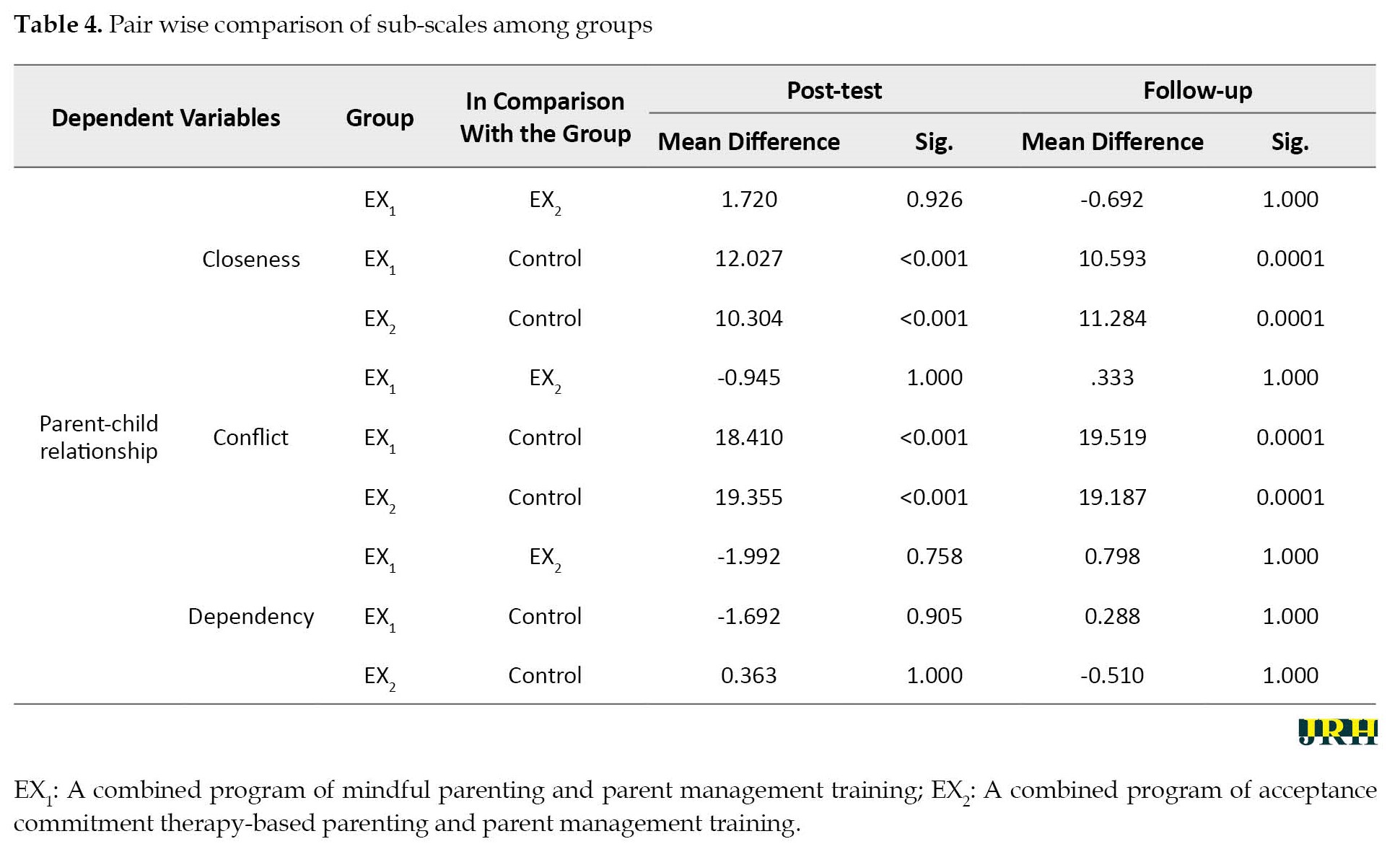

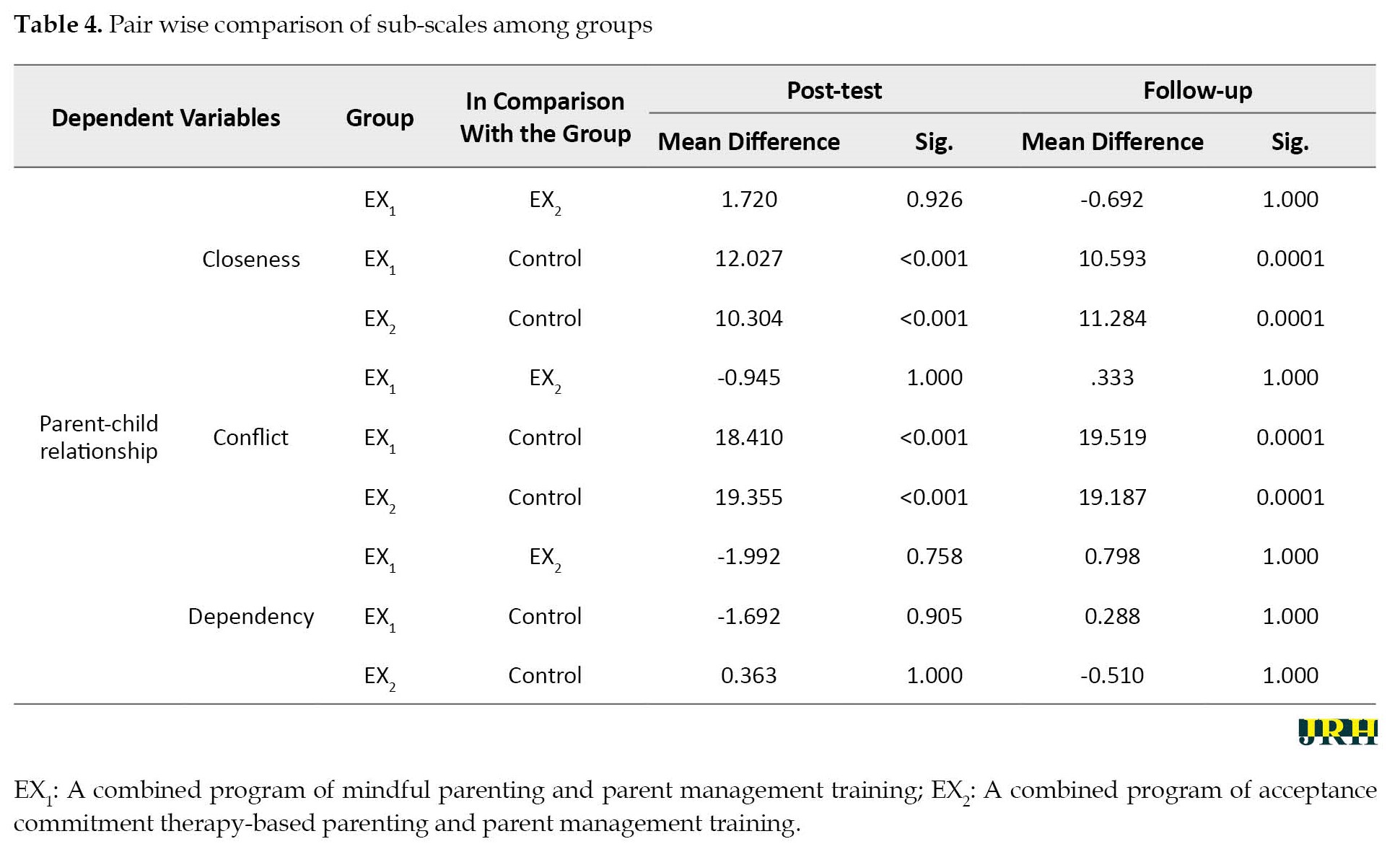

To further investigate differences between groups, the Bonferroni test was employed to compare research variables. Table 4 presents the results of this analysis.

A significant difference is observed between the test and control groups in the conflict and closeness variables. However, it is noteworthy that parent-child dependency in both the experimental groups has not shown a significant change compared to the control group. In other words, neither of the combined programs has resulted in a significant difference in parent-child dependency.

Discussion

This study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of two combined programs, namely ACT-based parenting and PMT, and mindful parenting and PMT, on the parent-child relationship. The data analysis revealed that both combined programs had a significant impact on reducing parent-child conflict and enhancing closeness. However, neither of the programs showed a significant effect on parent-child dependency. These results remained consistent during the three-month follow-up period. It is worth mentioning that the results of this study are consistent with the existing research literature regarding the influence of a combined program of mindful parenting and PMT [30, 31]. Gershy et al. [30]examined the effectiveness of combining mindfulness skills with parenting education in families with children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They integrated a behavioral program with a mindfulness training program and found that this combined intervention led to reduced reactive behaviors and improved emotion regulation in mothers. Consequently, these behavioral changes in parents resulted in an enhanced parent-child relationship and a decrease in their conflicts. These results are consistent with the results of the current study. Mah et al. [21] investigated the effectiveness of a mindfulness-enhanced parenting education program in families with children diagnosed with ADHD. They also combined a behavioral program with a mindfulness training program and found that this combined intervention led to increased parental self-efficacy, reduced harsh discipline practices, and improved parental self-regulation in families with children with ADHD. As a result of these changes in parenting style, the parent-child relationship improved, which is consistent with the results of the current study.

To elucidate this result, it can be posited that the combined program facilitates emotional awareness in parents, about both themselves and their children. This heightened emotional awareness empowers parents to respond consciously and calmly to their child’s challenging behaviors, rather than resorting to reactive and habitual responses [32]. Moreover, the program equips parents with the ability to focus on their child and their present behavior, enabling them to foster a sense of closeness through non-judgmental acceptance. This non-judgmental acceptance, in turn, allows parents to regulate their emotions independently of past experiences and emotions. Consequently, they become attuned to their children’s voices, comprehend their needs, and engage in positive interactions with them [34]. The combined program serves as a preventive measure against the intergenerational transmission of problems by educating parents about the impact of incompatible schemas. Through various exercises and practices, parents are empowered to avoid ineffective responses stemming from their schemas.

In this combined program, by incorporating an understanding of the negative consequences of fight-flight and freeze responses in parent-child interactions, proactive measures are taken to prevent exaggerated reactions to children’s negative behaviors in challenging parenting situations, leading to a reduction in negative conflicts between parents and children, and an improvement in their relationships [34]. Parents acquire strategies to distance themselves from automatic responses, thereby averting impulsive reactions towards their children and enabling them to make more rational decisions in the moment. When parents become conscious of their emotional reactivity and personally experience it, they exhibit less pronounced reactions towards their children and can utilize their learned parenting knowledge and skills. Consequently, their capacity for emotional regulation and coping is reinforced. This heightened emotional awareness empowers parents to better comprehend their child’s emotions. By embracing non-judgmental acceptance and directing attention towards their breathing, parents can pause before reacting to their child, resulting in a decrease in parental stress levels and a reduction in emotional dysregulation [34].

In mindfulness, parents learn to fully acknowledge and accept their experiences, both positive and negative. When parents recognize and accept their reactions as valid, they can adopt a more compassionate and empathetic stance toward themselves and their children [26]. As a result, the level of conflict between parents and children is reduced, leading to an improvement in the parent-child relationship.

One reason why parents may engage in negative behaviors towards their children, despite their desires, is due to negative experiences from their childhood. They interact with their child in a manner that reflects how they were treated as children. In this combined program, raising parents’ awareness of the impact of their maladaptive patterns prevents the transfer of intergenerational problems to the child. Through engaging in specific exercises, parents become capable of overcoming ineffective responses driven by their maladaptive patterns [20].

The present study yielded another significant finding, demonstrating the positive impact of the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT on enhancing the parent-child relationship. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal the effectiveness of parenting intervention combining PMT and ACT in improving the parent-child relationship. Our results are consistent with a previous study that investigated the combined intervention of stepping stones triple P (SSTP) and ACT, which resulted in improved functional performance and quality of life for children with cerebral palsy, as well as enhanced parental adjustment [19]. The SSTP intervention in that study, similar to the PMT program used in our research, focused on modifying child behavior. However, the distinction lies in using ACT parenting based on Coyne and Murrell [28] in our current study. Another study examined the combined intervention of SSTP and ACT, which also bears some resemblance to our research. Their results showed the intervention’s impact on reducing child behavioral and emotional problems, as well as dysfunctional parenting styles such as over-reactivity, among parents of children with pediatric acquired brain injury [18]. This highlights the notion that by modifying parenting styles, the parent-child relationship can improve, consequently leading to a reduction in the child’s behavioral and emotional difficulties [25].

Based on the theoretical underpinnings of the cognitive fusion component within the ACT framework, it is evident that cognitive fusion can lead to conflicts and ineffective interactions between parents and children. Cognitive fusion refers to the tendency of individuals to consider their negative thoughts as absolute truth and subsequently respond to various situations based on these distorted cognitions. Negative thoughts, such as “my child will never change” or “their nature is inherently flawed” can significantly influence parental reactions. Thus, the core principle of the ACT model is to teach parents to be responsive to their child’s needs in the present moment, rather than reacting to their negative thoughts [35]. This therapeutic approach helps parents develop the capacity to recognize and distance themselves from these thoughts, leading to an enhancement in their cognitive flexibility. Consequently, when parents can perceive these thoughts as mere cognitive events that do not necessarily reflect reality, their judgments, interpretations, and perceptions become less impactful, enabling them to focus more on the immediate reality and demands of the situation at hand [36]. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the quality of the parent-child relationships improved in correlation with the level of psychological flexibility displayed by parents. In instances where parents lack psychological flexibility, they tend to resort to maladaptive coping strategies when engaging with their children [37]. Conversely, increased psychological flexibility among parents is associated with improved parent-child relationship.

This combined program facilitates parents in recognizing and acknowledging their negative feelings and thoughts, reducing experiential avoidance, and promoting acceptance rather than suppression or control of their thoughts. A transformation exists in the relationship between parents and their emotions and thoughts. By identifying parental values, parenting, and life acquire new significance in the parents’ minds, enabling them to focus on making changes aligned with these values where feasible. This helps parents and children accept aspects of life where change is not possible. In the present study, this combined program enhanced the parent-child relationship between acceptance, and awareness, improved emotional regulation by parents, and fostering non-judgmental observation. However, the study revealed that neither of the combined programs produced a significant difference in parent-child dependency, potentially attributable to the educational content. Neither of the interventions specifically targeted reducing parent-child dependency. The focus of both interventions was primarily on mitigating parent-child conflict and fostering closeness. Cultural differences between Eastern and Western traditions may contribute to varying perspectives on child dependency. Dependency is regarded as a value in traditional Eastern culture, while Western culture emphasizes individuality and independence. In the West, efforts are made to promote children’s intellectual and behavioral independence from a young age. In contrast, in traditional Iranian culture, the value of dependence is recognized, and parents do not perceive the child’s dependence on them or their dependence on the child as negative. None of the combined programs effectively altered the level of parent-child dependency.

The research results indicated no significant difference in the effectiveness of the combined programs in improving the parent-child relationship, possibly due to the similarities between the programs. Mindful parenting and ACT-based parenting both belong to the third wave of cognitive-behavioral therapy and aim to enhance parenting through changes in parental cognition and emotions. Both approaches emphasize compassion, and kindness, reducing self-criticism, and fostering non-judgmental acceptance of both self and child. Mindfulness and non-judgmental observation are key mechanisms in ACT-based parenting, leading to incorporating mindfulness techniques, such as attentive listening, mindful walking, and understanding the child in the approach. The shared concepts and techniques between these two parenting styles contribute to their similarities because these concepts and techniques are prevalent in the mindful parenting approach as well.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that both the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT, as well as the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, have proven efficacy in reducing conflicts and fostering closeness within the parent-child relationship. However, it is essential to note that neither of these programs significantly influences the level of dependence between parents and children. Therefore, it may be necessary to incorporate additional interventions or targeted approaches specifically addressing parent-child dependency to address this aspect effectively. The study reveals no significant difference in the effectiveness of the two programs in improving the parent-child relationship. Both interventions yield comparable outcomes, making them equally viable options for enhancing parent-child interactions. The stability of the results observed during the follow-up phase highlights the enduring benefits of these combined programs. This suggests that practitioners and professionals in parenting interventions can confidently utilize both the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT, as well as the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, to facilitate positive parent-child relationships. To further advance the field, future research endeavors can focus on investigating additional interventions targeting parent-child dependency and exploring strategies to enhance the effectiveness of combined programs in improving various dimensions of the parent-child relationship.

These results provide practical insights and recommendations for professionals working in the field, offering evidence-based approaches to enhance parent-child relationships and foster healthy family relationships.

Study limitations

The current research has certain limitations that warrant careful consideration. Firstly, the use of the convenience sampling method in this study may restrict the generalizability of the results. Because participants were selected based on their accessibility and willingness to participate, the sample may not be fully representative of the entire population. Consequently, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the results to broader contexts. Another limitation of the study pertains to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research was conducted during a period when COVID-19 restrictions were in effect, which affected the implementation of certain components of the intervention. Specifically, due to the necessity of adhering to health protocols, the practice of “mindful eating” cannot be performed during the sessions. Instead, the researcher provided recorded materials for participants to engage in mindful eating exercises at home. This adaptation may have influenced the effectiveness and fidelity of the intervention. It is crucial to acknowledge these limitations because they have the potential to influence the generalizability and robustness of the research results. Future studies should consider employing more diverse sampling methods and exploring alternative strategies to address challenges posed by external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. By doing so, a more comprehensive understanding of the topic can be attained.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was conducted by ethical guidelines and obtained approval from the relevant authorities. The Clinical Trial Registration Center of Iran (IRCT) (Code IRCT20211006052688N1) approved the study on December 6, 2021, as well as by Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Code IR.SEMUMS.REC.1400.191) on October 26, 2021. Throughout the study, ethical principles were strictly adhered to, ensuring the confidentiality and privacy of the mothers’ information. All participating mothers provided informed consent before their involvement in the research. It is essential to note that the intervention implemented in this study posed no harm or adverse effects to the participants.

Funding

This paper originated from the PhD dissertation of Farzaneh Kosari, approved by Department of Psychology, Mahdishahr Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: Parviz Sabahi; Investigation: Farzaneh Kosari; Data collection: Farzaneh Kosari; Data analysis: Parviz Sabahi; Writing the original draft: Farzaneh Kosari; Review, editing and supervision: Parviz Sabahi and Shahrokh Makvand Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the mothers participating in the research who made it possible to conduct this research.

References

The formation of an individual’s relationship with oneself and others is significantly influenced by their experiences during infancy and childhood in the context of their primary caregiver. These early experiences have a subsequent impact on their relationships with both themselves and others. Parent-child relationship plays a fundamental role because it serves as the child’s initial introduction to the realm of communication and holds immense importance in fostering feelings of security and love [1]. Children depend on the reciprocal influence exerted by their parents because they keenly observe their behaviors and engage in interactions with them. These interactions serve as a foundation for children to develop an understanding of the social dynamics that encompass their lives. This mutual influence between parents and children assumes a pivotal role in shaping a child’s overall growth and development. Hence, it can be asserted that the parent-child relationship represents a dynamic amalgamation of distinctive behaviors, emotions, and individual expectations [2]. The parent-child relationship encompasses various modes of communication, encompassing verbal exchanges, visual observations, auditory perceptions, mutual understanding, accessibility, and other means of fostering interaction. It is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that is influenced by several key factors, including parental attitudes, levels of acceptance, behavior management strategies, social competence, self-esteem, parental knowledge and skills, self-assurance, and parenting beliefs regarding child-rearing [3]. These factors collectively shape the quality of parent-child relationships and maternal emotional caregiving while creating an environment characterized by minimal conflict [4]. The parent-child relationship can significantly influence children’s mental health. Numerous studies have provided evidence for the significant impact of the quality of parent-child relationships, particularly the mother-child relationship, on children’s psychological well-being, resulting in long-lasting effects [5, 6].

Undoubtedly, during childhood, parents and the parent-child relationship hold a prominent position as significant influencers in the development of social and psychological dimensions. The quality of parent-child relationships and the overall family environment serve as a fundamental factor that shapes the children’s well-being [7]. Conversely, obstacles encountered in parent-child interaction pose potential risks to a child’s developmental trajectory. Enhancing the quality of parent-child interaction has been associated with decreasing behavioral issues among children, promoting prosocial behaviors, cultivating effective parenting skills, such as firm discipline and structure, as well as alleviatingparental stress and tension [8].

Considering the paramount significance of the psychological well-being of parents and children, along with the crucial role of maintaining a wholesome parent-child relationship that fosters family well-being, it becomes imperative to address the pivotal and influential factors embedded within parenting practices. Consequently, a multitude of educational programs and interventions have been meticulously developed and executed, seeking to educate and empower parents. Among these programs, parent management training (PMT) emerges as one of the prevailing and efficacious approaches to parenting education, consistently substantiated by empirical evidence [9]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that such comprehensive training can effectively enhance the regulation of parents’ emotions, foster greater compassion towards both the parent and the child, and mitigate the child’s behavioral difficulties [10]. Moreover, this program has a significant impact on reducing aggressive parenting styles and enhancing parental self-regulation [11]. By enhancing parenting skills and diminishing negative emotions while cultivating positive emotions among parents [12], this intervention holds promise to foster a healthier parent-child relationship. In recent years, a notable intervention that has garnered significant attention is the integrated approach combining PMT and mindful parenting. This integrated program emphasizes active listening, and non-judgmental acceptance of both oneself and the child, and places a strong emphasis on mindfulness and non-judgmental comprehension of the child’s challenges, while consciously avoiding automatic parenting patterns. Furthermore, the combined program aims to break the intergenerational cycle of problems by addressing the parents’ schemas [13]. In addition, to enhance parenting skills, a recent intervention that has gained attention is mindful parenting, which focuses on promoting mental health and preventing psychological and behavioral disorders in children [14]. This approach incorporates mindfulness practices into the realm of parenting. Through this intervention, parents undergo training to redirect their attention from problematic child behaviors, damages, and parental distress toward the present moment and the unfolding experience in an authentic manner [15]. Research has demonstrated that mindful parenting has yielded positive outcomes in the parent-child relationship and has reduced parental tension in mothers. It has also been associated with a decrease in children’s behavioral problems [16].

An additional noteworthy intervention program is the combination of acceptance commitment therapy (ACT) with PMT. This program aims to assist parents in recognizing and accepting their emotions and concerns, aligning their actions with their values during challenging interactions with their child, and identifying and eliminating ineffective behaviors. Furthermore, it emphasizes the cultivation of mindfulness and non-judgmental observation while seeking to reduce experiential avoidance through compassion and kindness, ultimately reducing self-criticism among parents during difficult parenting moments [17]. Consequently, it promotes parents’ persistence in addressing crucial issues, thereby enhancing the significance of the parent-child relationship [18]. This approach has demonstrated efficacy in reducing parental stress and depression, enhancing quality of life, and improving child performance [19]. Additionally, this intervention fosters parental acceptance and enhances adaptive modes of interaction with the child.

Research studies have indicated that the combined utilization of these two programs has demonstrated greater effectiveness compared to non-combined programs [18, 20, 21]. However, it is essential to note that a lack of empirical evidence directly compares the outcomes of these combined programs. Both ACT and mindfulness-based interventions share several similarities and fall under the umbrella of third-wave treatments [22]. These therapeutic approaches aim to explore and address the parent’s cognitive processes, emotional regulation, and overall well-being.

In the realm of education and child development, the involvement of parents holds paramount importance. They serve as vital guides and creators of nurturing environments for their children. While educational institutions play a significant role in shaping students’ academic and social skills, the parent-child relationship, effective communication, and parental engagement have emerged as crucial elements in fostering a child’s learning and overall development. Consequently, recognizing the significance of cultivating strong parent-child connections and promoting effective communication becomes imperative for achieving optimal educational outcomes for both the child and the parent. Furthermore, parental engagement not only enhances their comprehension but also serves as a driving force for academic achievement and the acquisition of essential life skills. Thus, it is crucial to acknowledge the indispensable role of parents in their children’s education and to emphasize the importance of fostering effective communication to facilitate growth and success in both academic and personal domains.

The objective of this research was to determine the relative efficacy of two interventions in enhancing the parent-child relationship. Specifically, the study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of a combined program consisting of ACT-based parenting and PMT with a combined program comprising mindful parenting and PMT. The primary focus was to assess the impact of these interventions on the enhancement of the parent-child relationship.

Methods

The study used a quasi-experimental design, specifically employing a pre-test and post-test method, with a three-month follow-up period. To enhance the validity of the results, a control group was incorporated. The statistical population comprised all mothers of preschool children in Semnan City, Iran in 2022.

One method to estimate sample size in quasi-experimental designs is the use of the Equation 1:

1. N=(2×(Zα+Zβ)/Δ)2

In this formula, n represents the number of samples in each group. Zα and Zβ represent the critical values from the normal distribution for the significance level (α) and statistical power (1-β), respectively. Δ represents the meaningful difference between the two groups. For example, to determine sample size in each group with a significance level of 0.05, statistical power of 0.8, and assuming a meaningful difference between the groups of 5 units, we can extract the corresponding values of Zα and Zβ from the relevant table and substitute them into the formula to calculate the sample size [23]. If we want to estimate the minimum sample size, we can use the following values:

Zα=1.96 (for a significance level of 0.05)

Zβ=0.84 (for a statistical power of 0.8)

Consequently, by substituting these values into the formula, we can determine the minimum sample size required in each group to ensure a minimum of 12 to 15 participants in each group.

Using convenience sampling, 36 mothers were selected and were then randomly assigned to three groups, two experimental groups and one control group. Random assignment was achieved through a lottery-based method without replacement. Twelve mothers received training based on the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, while another twelve mothers were educated using the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT. These training sessions were conducted over eight weeks, with two-hour sessions held weekly. The control group was placed on a waiting list.

The study implemented specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the meticulous selection of participants. The inclusion criteria included several essential factors. First, participants were required to have a child aged between 5 and 7 years. They were expected to reside with a spouse and show a willingness to participate in the parenting sessions. Mothers were expected to hold a minimum educational qualification of at least a high school diploma, showing a level of educational attainment. In contrast, the study also defined exclusion criteria to identify individuals who did not meet the desired eligibility. The presence of psychological disorders and the usage of psychiatric medications by either the mother or the child were evaluated through psychological interviews conducted by the researcher. Participants displaying these conditions were excluded from the study. Also, chronic diseases affecting either the mother or the child were considered grounds for exclusion due to their potential to confound the study results. Other exclusion criteria included absenteeism from over two training sessions, marital separation or divorce, and a diminishing tendency to actively engage in the research. It is crucial to ensure the commitment and involvement of participants throughout the study. Finally, individuals simultaneously receiving psychological services and participating in the study were also excluded because this dual involvement can introduce additional variables that may influence the outcomes.

By carefully having these inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study was conducted to create a more homogeneous and appropriate participant group for the research, ensuring the integrity and validity of the results.

Measures

Pianta parent-child relationship scale (PCRS): Pianta parent-child relationship scale (PCRS), developed by Pianta in 1992 [24], is a 33-item instrument utilized to assess various aspects of the parent-child relationship. It encompasses dimensions, such as parent-child dependency, perceived conflicts, and the degree of closeness. The scale comprises three sub-scales, conflict, closeness, and dependency. The conflict sub-scale includes the following questions, 2, 4, 7, 21, 23, 24, 12, 14, 17, 19, 25, 26, 32, 33, 27, 28, and 31. Questions related to closeness are numbered as 6, 8, 10, 13, 1, 3, 5, 16, 29, and 30. Finally, the dependency sub-scale consists of questions 22, 18, 11, 15, 9, and 20. In addition, a measure of positive relationship was obtained by combining responses from all items. A 5-point Likert scale was employed to rate the questionnaire, where higher scores indicate a more positive parent-child relationship. Driscoll and Pianta reported the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the conflict, closeness, dependency sub-scales, and the total positive relationship as 0.75, 0.74, 0.69, and 0.80, respectively [24]. These coefficients indicate the internal consistency and reliability of the scale. The PCRS serves as a comprehensive tool to assess various dimensions of the parent-child relationship and has demonstrated satisfactory reliability through the reported Cronbach’s α coefficients. In the Iranian context, the reliability of the sub-scales of the PCRS, namely conflict, closeness, and dependency, was reported to be 0.68, 0.71, and 0.73, respectively, using Cronbach’s α coefficient. Additionally, the sub-scale demonstrated a total positive relationship with a total reliability of 0.78. These results indicate satisfactory internal consistency and reliability of the PCRS sub-scales in assessing the parent-child relationship within the Iranian population [25]. Furthermore, in the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.79, indicating good reliability for the questionnaire.

Research implementation process

Initially, the potential participants were invited to attend a briefing session where the research objectives and session procedures were thoroughly explained. During this meeting, ethical considerations, including the principles of confidentiality and the protection of parents’ information, were emphasized. Subsequently, the research questionnaire was distributed to the parents for sampling purposes, and eligible participants were selected as the study sample. Random assignment was employed to allocate mothers into the control and experimental groups, each consisting of 12 members. The control group was placed on a waiting list while the training sessions commenced. The training program spanned two months, and upon completion, a post-test assessment was administered to all three groups. Furthermore, a three-month follow-up evaluation was conducted to assess the long-term effects.

Twelve mothers in one experimental group underwent the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, which consisted of eight weekly sessions, with each session lasting two hours. Bögels and Restifo developed the mindful parenting program in 2014 [26], and the PMT program was based on Sanders’ model [27] as the following:

First session: Explaining automatic parenting, fight-flight, and freeze reactions, as well as positive interaction training.

Second session: Adopting a perspective of seeing a child with a beginner’s mind and conducting an exploration of their body, while also emphasizing the importance of employing the rationale behind physical affection.

Third session: Cultivating self-kindness and integration of Yoga practices, and guiding effective verbal communication and empathetic engagement with children.

Fourth session: Emphasizing the significance of responding to rather than reacting impulsively to a child’s behavior, along with teaching methods for delivering appropriate praise.

Fifth session: Explaining ineffective inter-generational models and training techniques for effectively giving instructions and setting boundaries for children.

Sixth session: Providing instruction on how to rebuild the parent-child relationship and implementing logical consequences for behavior.

Seventh session: Mindful approach to determining rules and regulations, as well as utilizing behavior chart training to foster positive behavioral patterns.

Eighth session: Summarizing the principles of mindful parenting and highlighting the importance of avoiding avoidance and deprivation in the parent-child relationship.

Twelve mothers in one experimental group underwent the combination of ACT-based parenting with PMT which consisted of eight weekly sessions, with each session lasting two hours. The ACT-based parenting was derived from “the joy of parenting: An acceptance and commitment therapy guide to effective parenting in the early years” by Murrell and Coyne in 2009 [28], and PMT was based on Sanders’ model [29] as the following:

First session: Parents’ familiarity with their psychological processes and the potential impact of reactive parenting on both short-term and long-term outcomes. Implementation of positive interaction training.

Second session: Exploring parental values and utilizing the metaphor of the “islands of competence” to enhance understanding. Presenting the rationale behind the importance of physical affection.

Third session: Conducting a functional analysis of challenging situations involving children and providing problem-solving strategies was discussed in this section. Additionally, it offers guidance on effective verbal communication and empathetic engagement with children.

Forth session: Providing mindfulness training to cultivate the ability to acknowledge and experience various emotions without avoidance. Teaching effective strategies for praising and giving instructions to children.

Fifth session: Planning strategies to manage tantrums and adjusting consequences are explored in this section. It further explains the concept of logical consequences for behavior and emphasizes the importance of their implementation.

Sixth session: This session addresses the importance of recognizing parenting mistakes and fostering the skill of self-reflection. It guides implementing behavior charts as a tool to monitor and reinforce daily behaviors.

Seventh session: Comparing oneself to the ideal parent and practicing self-care. Strategies for addressing behavioral problems and teaching avoidance.

Eighth session: Fostering commitment in mothers to adhere to the established plan is the focus of this part. It also provides instruction on teaching the concept of deprivation and its underlying principles.

It is noteworthy that the researcher has completed a comprehensive training program on PMT and parenting skills based on ACT, in addition to mindful parenting, at esteemed institutions under the guidance of highly qualified and experienced professional instructors.

The data analysis phase involved utilizing SPSS software, version 23 and applying multivariate covariance analysis.

Results

The Mean±SD in the mindful parenting group was 36.58±3.02 for mothers and 5.75±0.452 for children. In contrast, the ACT-based parenting group had a Mean±SD age of 35.75±3.10 for mothers and 6.50±0.52 for children. The Mean±SD age of the control group was 35.08±3.98 for mothers and 5.42±0.51 for children. Regarding the education level of mothers in the mindful parenting group, the frequency and percentage distribution were Bachelor’s degree 7(58.3%) and master’s degree 5(41.7%). In the ACT-based parenting group, the frequency and percentage distribution were 7 (58.3%) for a Bachelor’s degree and 5(41.7%) and for a master’s degree. In the control group, the frequency and percentage distributions were 3(0.25%) for diplomas, 7(58.3%) for Bachelor’s degrees, and 1(8.3%) each for Master’s and PhD degrees. The distribution of working mothers and housewives in the mindful parenting group was 8(66.5%) and 4(33.3%), respectively. In the ACT-based parenting group, 9(75%) were working mothers and 3(25%) were housewives. Similarly, in the control group, 5(41.7%) were working mothers and 7(58.3%) were housewives.

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD values of the control and experimental groups in three phases, pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

The results showed that the mean score of the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT increased in the post-test and follow-up stages. Similarly, in the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT, the mean score increased in the post-test but showed a decreasing trend in the follow-up stage. To analyze the data and control the pre-test scores, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was employed, using the pre-test scores of the research variables as covariance variables.

Before conducting MANCOVA, the necessary assumptions were examined. The normality of data in each group was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The significance level of all dependent variables in both the control and experimental groups was P>0.05, indicating the normality of the data. Additionally, the assumption of equivalence of covariance matrices was evaluated using Box’s M test, which showed no significant deviations in the post-test (Box’s M: 13.060, F=0.943, P=0.502) and follow-up (Box’s M: 17.818, F=1.28, P=0.219) stages. Levene’s test was employed to examine the assumption of homogeneity of variances for the dependent variable, and it was satisfied in the post-test, follow-up, and three sub-scales (P≥0.05). However, the results of Butler’s Sphericity test did not support this assumption (P=0.007). Therefore, more stringent tests, such as Pillai’s Trace were utilized.

Based on the F value and its significance level presented in Table 2, it can be concluded that a significant difference is observed between the research groups in the dependent variables, even after eliminating the effect of the pre-test.

Table 3 presents the results of the MANCOVA analysis, demonstrating a significant difference among the three groups (combination of ACT-based parenting and PMT, combination of mindful parenting and PMT, and control) in all closeness, conflict, and variables except for dependency.

To further investigate differences between groups, the Bonferroni test was employed to compare research variables. Table 4 presents the results of this analysis.

A significant difference is observed between the test and control groups in the conflict and closeness variables. However, it is noteworthy that parent-child dependency in both the experimental groups has not shown a significant change compared to the control group. In other words, neither of the combined programs has resulted in a significant difference in parent-child dependency.

Discussion

This study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of two combined programs, namely ACT-based parenting and PMT, and mindful parenting and PMT, on the parent-child relationship. The data analysis revealed that both combined programs had a significant impact on reducing parent-child conflict and enhancing closeness. However, neither of the programs showed a significant effect on parent-child dependency. These results remained consistent during the three-month follow-up period. It is worth mentioning that the results of this study are consistent with the existing research literature regarding the influence of a combined program of mindful parenting and PMT [30, 31]. Gershy et al. [30]examined the effectiveness of combining mindfulness skills with parenting education in families with children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They integrated a behavioral program with a mindfulness training program and found that this combined intervention led to reduced reactive behaviors and improved emotion regulation in mothers. Consequently, these behavioral changes in parents resulted in an enhanced parent-child relationship and a decrease in their conflicts. These results are consistent with the results of the current study. Mah et al. [21] investigated the effectiveness of a mindfulness-enhanced parenting education program in families with children diagnosed with ADHD. They also combined a behavioral program with a mindfulness training program and found that this combined intervention led to increased parental self-efficacy, reduced harsh discipline practices, and improved parental self-regulation in families with children with ADHD. As a result of these changes in parenting style, the parent-child relationship improved, which is consistent with the results of the current study.

To elucidate this result, it can be posited that the combined program facilitates emotional awareness in parents, about both themselves and their children. This heightened emotional awareness empowers parents to respond consciously and calmly to their child’s challenging behaviors, rather than resorting to reactive and habitual responses [32]. Moreover, the program equips parents with the ability to focus on their child and their present behavior, enabling them to foster a sense of closeness through non-judgmental acceptance. This non-judgmental acceptance, in turn, allows parents to regulate their emotions independently of past experiences and emotions. Consequently, they become attuned to their children’s voices, comprehend their needs, and engage in positive interactions with them [34]. The combined program serves as a preventive measure against the intergenerational transmission of problems by educating parents about the impact of incompatible schemas. Through various exercises and practices, parents are empowered to avoid ineffective responses stemming from their schemas.

In this combined program, by incorporating an understanding of the negative consequences of fight-flight and freeze responses in parent-child interactions, proactive measures are taken to prevent exaggerated reactions to children’s negative behaviors in challenging parenting situations, leading to a reduction in negative conflicts between parents and children, and an improvement in their relationships [34]. Parents acquire strategies to distance themselves from automatic responses, thereby averting impulsive reactions towards their children and enabling them to make more rational decisions in the moment. When parents become conscious of their emotional reactivity and personally experience it, they exhibit less pronounced reactions towards their children and can utilize their learned parenting knowledge and skills. Consequently, their capacity for emotional regulation and coping is reinforced. This heightened emotional awareness empowers parents to better comprehend their child’s emotions. By embracing non-judgmental acceptance and directing attention towards their breathing, parents can pause before reacting to their child, resulting in a decrease in parental stress levels and a reduction in emotional dysregulation [34].

In mindfulness, parents learn to fully acknowledge and accept their experiences, both positive and negative. When parents recognize and accept their reactions as valid, they can adopt a more compassionate and empathetic stance toward themselves and their children [26]. As a result, the level of conflict between parents and children is reduced, leading to an improvement in the parent-child relationship.

One reason why parents may engage in negative behaviors towards their children, despite their desires, is due to negative experiences from their childhood. They interact with their child in a manner that reflects how they were treated as children. In this combined program, raising parents’ awareness of the impact of their maladaptive patterns prevents the transfer of intergenerational problems to the child. Through engaging in specific exercises, parents become capable of overcoming ineffective responses driven by their maladaptive patterns [20].

The present study yielded another significant finding, demonstrating the positive impact of the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT on enhancing the parent-child relationship. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal the effectiveness of parenting intervention combining PMT and ACT in improving the parent-child relationship. Our results are consistent with a previous study that investigated the combined intervention of stepping stones triple P (SSTP) and ACT, which resulted in improved functional performance and quality of life for children with cerebral palsy, as well as enhanced parental adjustment [19]. The SSTP intervention in that study, similar to the PMT program used in our research, focused on modifying child behavior. However, the distinction lies in using ACT parenting based on Coyne and Murrell [28] in our current study. Another study examined the combined intervention of SSTP and ACT, which also bears some resemblance to our research. Their results showed the intervention’s impact on reducing child behavioral and emotional problems, as well as dysfunctional parenting styles such as over-reactivity, among parents of children with pediatric acquired brain injury [18]. This highlights the notion that by modifying parenting styles, the parent-child relationship can improve, consequently leading to a reduction in the child’s behavioral and emotional difficulties [25].

Based on the theoretical underpinnings of the cognitive fusion component within the ACT framework, it is evident that cognitive fusion can lead to conflicts and ineffective interactions between parents and children. Cognitive fusion refers to the tendency of individuals to consider their negative thoughts as absolute truth and subsequently respond to various situations based on these distorted cognitions. Negative thoughts, such as “my child will never change” or “their nature is inherently flawed” can significantly influence parental reactions. Thus, the core principle of the ACT model is to teach parents to be responsive to their child’s needs in the present moment, rather than reacting to their negative thoughts [35]. This therapeutic approach helps parents develop the capacity to recognize and distance themselves from these thoughts, leading to an enhancement in their cognitive flexibility. Consequently, when parents can perceive these thoughts as mere cognitive events that do not necessarily reflect reality, their judgments, interpretations, and perceptions become less impactful, enabling them to focus more on the immediate reality and demands of the situation at hand [36]. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the quality of the parent-child relationships improved in correlation with the level of psychological flexibility displayed by parents. In instances where parents lack psychological flexibility, they tend to resort to maladaptive coping strategies when engaging with their children [37]. Conversely, increased psychological flexibility among parents is associated with improved parent-child relationship.

This combined program facilitates parents in recognizing and acknowledging their negative feelings and thoughts, reducing experiential avoidance, and promoting acceptance rather than suppression or control of their thoughts. A transformation exists in the relationship between parents and their emotions and thoughts. By identifying parental values, parenting, and life acquire new significance in the parents’ minds, enabling them to focus on making changes aligned with these values where feasible. This helps parents and children accept aspects of life where change is not possible. In the present study, this combined program enhanced the parent-child relationship between acceptance, and awareness, improved emotional regulation by parents, and fostering non-judgmental observation. However, the study revealed that neither of the combined programs produced a significant difference in parent-child dependency, potentially attributable to the educational content. Neither of the interventions specifically targeted reducing parent-child dependency. The focus of both interventions was primarily on mitigating parent-child conflict and fostering closeness. Cultural differences between Eastern and Western traditions may contribute to varying perspectives on child dependency. Dependency is regarded as a value in traditional Eastern culture, while Western culture emphasizes individuality and independence. In the West, efforts are made to promote children’s intellectual and behavioral independence from a young age. In contrast, in traditional Iranian culture, the value of dependence is recognized, and parents do not perceive the child’s dependence on them or their dependence on the child as negative. None of the combined programs effectively altered the level of parent-child dependency.

The research results indicated no significant difference in the effectiveness of the combined programs in improving the parent-child relationship, possibly due to the similarities between the programs. Mindful parenting and ACT-based parenting both belong to the third wave of cognitive-behavioral therapy and aim to enhance parenting through changes in parental cognition and emotions. Both approaches emphasize compassion, and kindness, reducing self-criticism, and fostering non-judgmental acceptance of both self and child. Mindfulness and non-judgmental observation are key mechanisms in ACT-based parenting, leading to incorporating mindfulness techniques, such as attentive listening, mindful walking, and understanding the child in the approach. The shared concepts and techniques between these two parenting styles contribute to their similarities because these concepts and techniques are prevalent in the mindful parenting approach as well.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that both the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT, as well as the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, have proven efficacy in reducing conflicts and fostering closeness within the parent-child relationship. However, it is essential to note that neither of these programs significantly influences the level of dependence between parents and children. Therefore, it may be necessary to incorporate additional interventions or targeted approaches specifically addressing parent-child dependency to address this aspect effectively. The study reveals no significant difference in the effectiveness of the two programs in improving the parent-child relationship. Both interventions yield comparable outcomes, making them equally viable options for enhancing parent-child interactions. The stability of the results observed during the follow-up phase highlights the enduring benefits of these combined programs. This suggests that practitioners and professionals in parenting interventions can confidently utilize both the combined program of ACT-based parenting and PMT, as well as the combined program of mindful parenting and PMT, to facilitate positive parent-child relationships. To further advance the field, future research endeavors can focus on investigating additional interventions targeting parent-child dependency and exploring strategies to enhance the effectiveness of combined programs in improving various dimensions of the parent-child relationship.

These results provide practical insights and recommendations for professionals working in the field, offering evidence-based approaches to enhance parent-child relationships and foster healthy family relationships.

Study limitations

The current research has certain limitations that warrant careful consideration. Firstly, the use of the convenience sampling method in this study may restrict the generalizability of the results. Because participants were selected based on their accessibility and willingness to participate, the sample may not be fully representative of the entire population. Consequently, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the results to broader contexts. Another limitation of the study pertains to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research was conducted during a period when COVID-19 restrictions were in effect, which affected the implementation of certain components of the intervention. Specifically, due to the necessity of adhering to health protocols, the practice of “mindful eating” cannot be performed during the sessions. Instead, the researcher provided recorded materials for participants to engage in mindful eating exercises at home. This adaptation may have influenced the effectiveness and fidelity of the intervention. It is crucial to acknowledge these limitations because they have the potential to influence the generalizability and robustness of the research results. Future studies should consider employing more diverse sampling methods and exploring alternative strategies to address challenges posed by external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. By doing so, a more comprehensive understanding of the topic can be attained.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was conducted by ethical guidelines and obtained approval from the relevant authorities. The Clinical Trial Registration Center of Iran (IRCT) (Code IRCT20211006052688N1) approved the study on December 6, 2021, as well as by Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Code IR.SEMUMS.REC.1400.191) on October 26, 2021. Throughout the study, ethical principles were strictly adhered to, ensuring the confidentiality and privacy of the mothers’ information. All participating mothers provided informed consent before their involvement in the research. It is essential to note that the intervention implemented in this study posed no harm or adverse effects to the participants.

Funding

This paper originated from the PhD dissertation of Farzaneh Kosari, approved by Department of Psychology, Mahdishahr Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Semnan University.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: Parviz Sabahi; Investigation: Farzaneh Kosari; Data collection: Farzaneh Kosari; Data analysis: Parviz Sabahi; Writing the original draft: Farzaneh Kosari; Review, editing and supervision: Parviz Sabahi and Shahrokh Makvand Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the mothers participating in the research who made it possible to conduct this research.

References

- Qi H, Kang Q, Bi C, Wu, Q, Jiang L, Wu D. Are fathers more important? The positive association between the parent-child relationship and left-behind adolescents’ subjective vitality. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2023; 32:3612–24 [DOI:10.1007/s10826-023-02605-0]