Volume 14, Issue 4 (Jul & Aug 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(4): 299-312 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amedu A N, Dwarika V. Investigating the Economic Burden and Social Support in Individuals With Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Scoping Review. J Research Health 2024; 14 (4) :299-312

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2366-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2366-en.html

1- Department of Educational Psychology, Soweto Campus, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. , amosnnaemeka@gmail.com

2- Department of Educational Psychology, Soweto Campus, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

2- Department of Educational Psychology, Soweto Campus, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Keywords: Economic burden, Social support, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Scoping review, Individuals with PTSD

Full-Text [PDF 946 kb]

(2061 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4063 Views)

Full-Text: (1687 Views)

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the outcome of a mental disorder that arises from exposure of a person to devastating traumatic events, such as floods, wildfires, war, and severe assaults among others [1, 2]. An individual may be exposed directly or indirectly to traumatic events through experiencing the phenomenon, observing the experiences of others, or being regularly confronted with aversive details of such events [3]. It is estimated that more than 70% of adults worldwide have experienced at least one potentially devastating incident in their lifetime [4]. Therefore, direct or indirect exposure to traumatic events is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of PTSD, which is also associated with other forms of mental illness [5, 6]. According to the PTSD literature, 5.6% of individuals who have experienced trauma develop PTSD in their lifetime [7, 8] and this is particularly evident in individuals whose disposition is characterized by avoidance, severe anxiety, nightmares, flashbacks, etc. recurring dreams about the events, and negative changes in cognition. Therefore, due to the complexity of PTSD, its treatment is considered costly [9]. This implies that individuals with PTSD could experience a substantial economic burden.

Patients with PTSD face an economic burden that goes beyond direct healthcare costs and those associated with other mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety [9]. This means that the economic burden of PTSD on society includes the indirect costs resulting from poor productivity, disability payments, reduced quality of life (QoL), and increased burden on caregivers [10]. Data from the United States indicate that PTSD has an annual economic burden of $232 billion [9]. Accordingly, PTSD is a major psychological problem that needs serious attention. The recent COVID-19 state of emergency, civil unrest, and recurring national disasters are increasing the growing pressure on PTSD and its impact on the world population [9]. As a result, the prevalence of PTSD tends to increase at the same time as the economic burden increases. Because of this, patients with PTSD need social support to further their recovery.

Social support is an important social resource that can facilitate a person’s recovery from acute adverse stress events [11]. Various sources of social support are identified in the literature, including family, friends, non-governmental organizations, and the government. According to previous studies, providing timely social support can have a significant impact on how individuals cope with recovery from PTSD [11, 12]. The conceptualization of social support has been based on how it is perceived to be multifaceted and interactional. The effectiveness of social support depends more on recipients’ perceptions rather than the perception of its providers [13]. The multifactorial conception of social support provides more information on how a particular response of an individual or a society might affect an individual’s PTSD and how the different types of social support may interact [13]. The types of social support based on diverse views include positive support, negative support, and no support at all. Positive support includes tangible aid, emotional help, and informational support, while negative support is characterized by blame, disbelief, taking control of the recipients’ choices, and withdrawal from the support recipient. No support indicates the absence of positive and negative support. Positive support improves a person’s ability to recover quickly from trauma, while negative support may suppress a person’s natural coping mechanisms.

Therefore, conducting a scoping review to determine the global economic burden of PTSD is important for policymakers, as it informs them of its prevalence and devastating impact and allows them to prioritize the allocation of resources to minimize these impacts on individuals and society. Therefore, the literature needs to be reviewed to provide an overview of the latest empirical evidence regarding the economic burdens and social support for people with PTSD. This study demonstrates the economic burdens associated with PTSD and the social support provided to promote recovery for individuals with PTSD. We are hopeful that our findings will provide policymakers, educators, therapists, and governmental and non-governmental organizations with reliable and timely evidence of the economic burdens and the social support needed for people living with PTSD. We also believe that our findings will fill the gap in the current literature on various studies on economic burdens and social support related to PTSD patients.

Review questions

The research questions that guided the current study are as follows:

What economic burdens are associated with people with PTSD?

What social support is provided to promote recovery for people with PTSD?

Methods

A preliminary search was carried out for a scoping review on the economic burden of children and adults with PTSD and associated social supports for enhancing individual recovery from PTSD in several online databases, such as Google Scholars, PubMed, Wiley Online Library, Science Direct, Springer Nature, Frontier, Scopus, APA, PTSDpubs, National Library of Medicine, the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, and JBI Evidence synthesis. No existing studies concerning a scoping review on this topic were identified. The guideline for preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis was adopted in this study [14]. This study was conducted following JBL methodological guidance [15]. It ensures the appropriateness of the scoping review in terms of data extraction, analysis, presentation, and clarification of the implications for practical research.

Literature search

We conducted an extensive literature search in several electronic databases and other journal databases, such as Scopus, APA, National Library of Medicine, Wiley Online Library, Science Direct, PTSDpubs, Frontier, Google Scholars, Elsevier. Keywords and search terms were formulated by the research team with the help of an experienced digital librarian. We used the following keywords and terms to search the database which included “economic burden of PTSD patients,” “cost of PTSD,” “financial burden of PTSD,” “financial constraints of individuals with PTSD,” “health care cost of PTSD,” and “medical cost of PTSD.” Concerning social support, the search terms used were “assistance for patients with PTSD,” “social aid for PTSD,” “social relief for PTSD,” “social welfare for PTSD,” “support services for PTSD,” “social care for individuals with PTSD,” and “community services for PTSD.” We limited our search to the period from 2000 to 2023. The date limit was used to search databases that did not have a controlled vocabulary or thesaurus. The reference list of related articles was also explored.

Eligibility of studies

Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals were analyzed. Based on the research questions formulated to guide the study, intervention studies and historical studies on the economic burden and social support of PTSD patients were excluded. Quantitative studies on the economic burden and social support of PTSD patients were included in the study. We also included reviews that captured either the economic burden or the social support of PTSD patients. A book of abstract articles was also included in the review to facilitate uniformity in reporting published articles. Opinion papers and commentaries were excluded from the review. Non-English language articles were excluded. All participants were included in this study, regardless of their age; therefore, no age restrictions were imposed. This allowed the researchers to assess the broad literature and identify the knowledge gap.

Data extraction

The data extraction was carried out by the first author (AN). The rationale for extracting the data points and the sources of the article were checked by the second author (DV). Both authors reached a consensus regarding the resolution of ambiguous data points. Three types of data were collected from selected articles. First, data was collected based on the empirical features of the reviewed articles (year of publication, first author, design, country, population, primary outcome, and result). In addition, data on economic burdens were extracted and categorized into direct cost, indirect cost, and annual cost. In addition, data comparing the economic burdens of males and females was extracted. All monetary values were converted and presented in US dollars using the purchasing power parity index [16]. Third, social support data were extracted and organized according to the relationship between social support and PTSD symptoms, the effectiveness of social support for individuals with PTSD, and the mediating roles of social support.

Results

Study selection

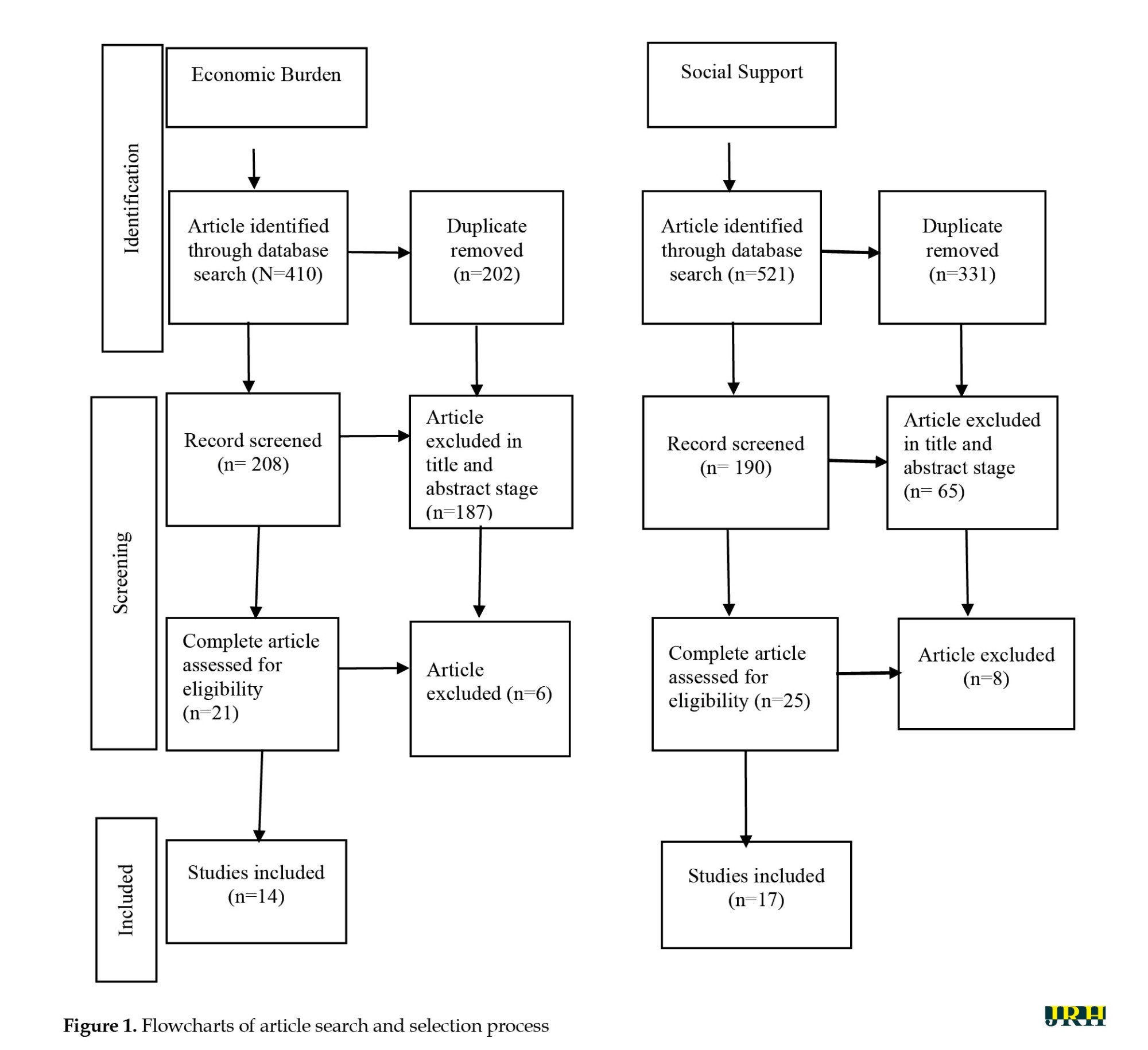

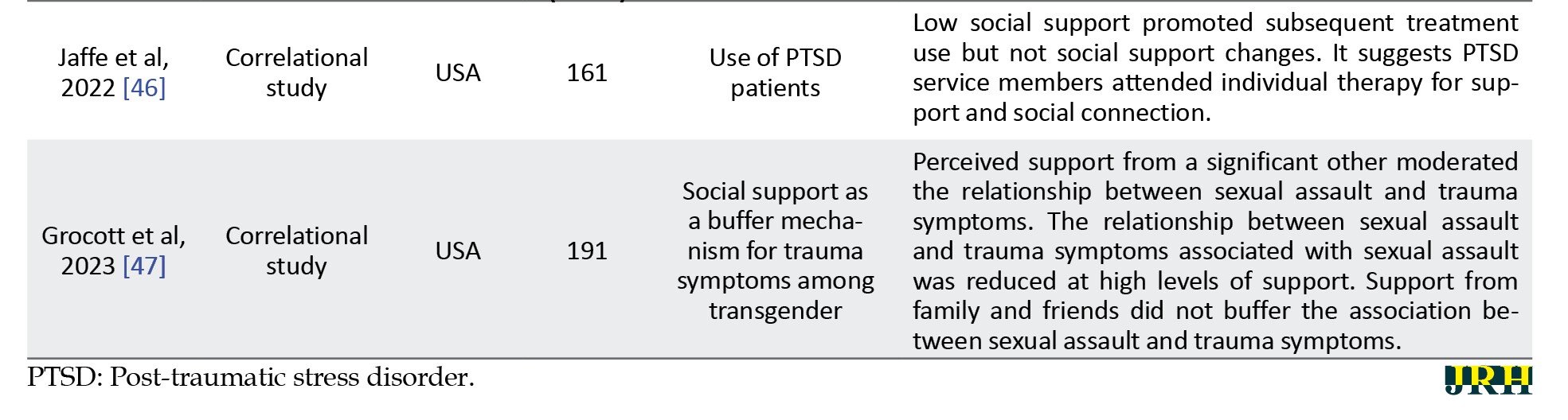

This study identified 410 articles on economic burdens and 521 articles on social support through a comprehensive search of academic databases. These articles underwent a double filtering that removed 202 articles from the economic burden literature and 331 articles from the social support. The remaining 208 and 190 articles on economic burden and social support, respectively, were further screened for title and abstract suitability. At this point, 187 articles were removed from the economic burden literature and 165 articles from the social support literature. Finally, 14 articles were assessed for their economic burden and 17 articles for their social support (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

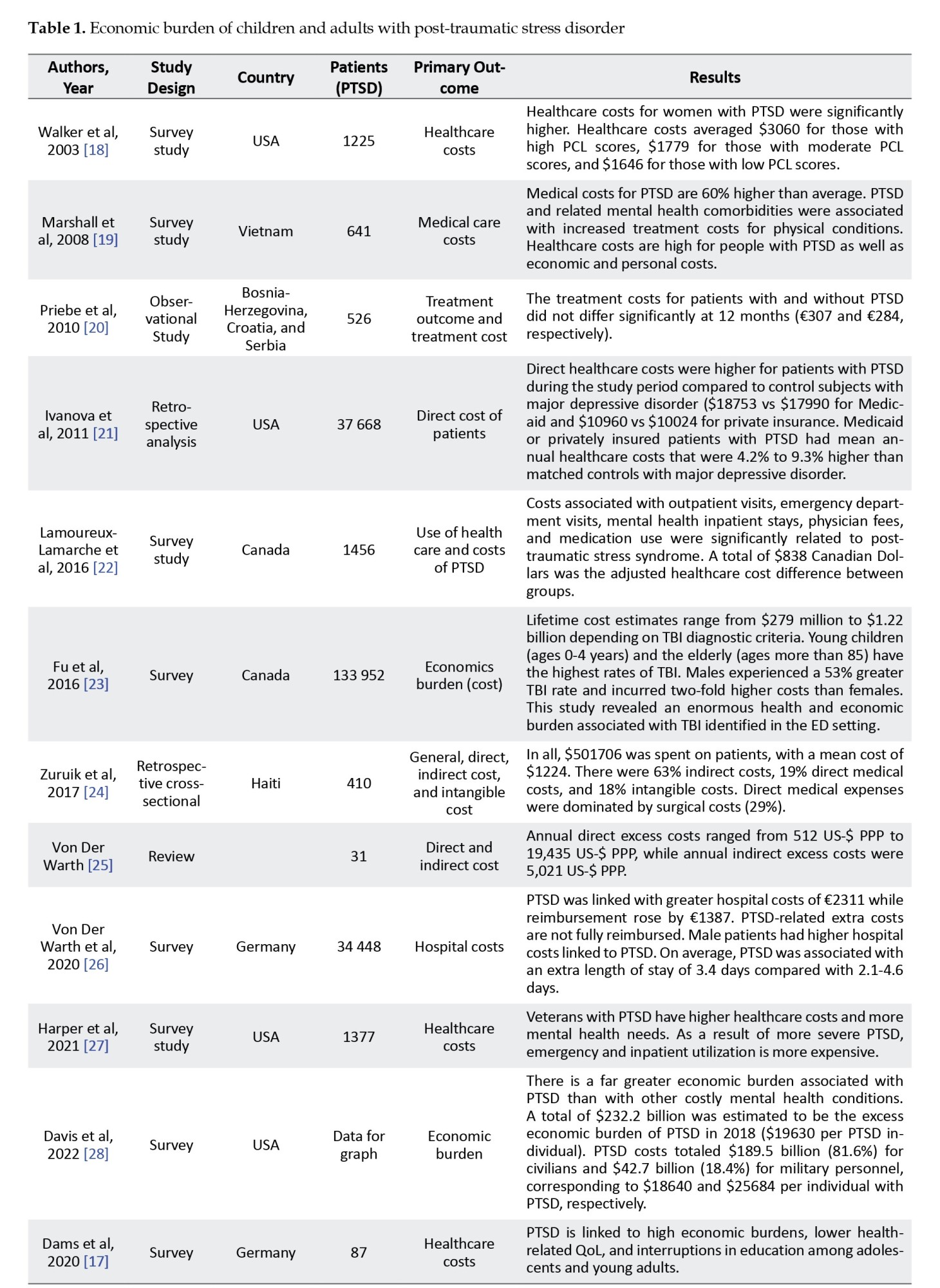

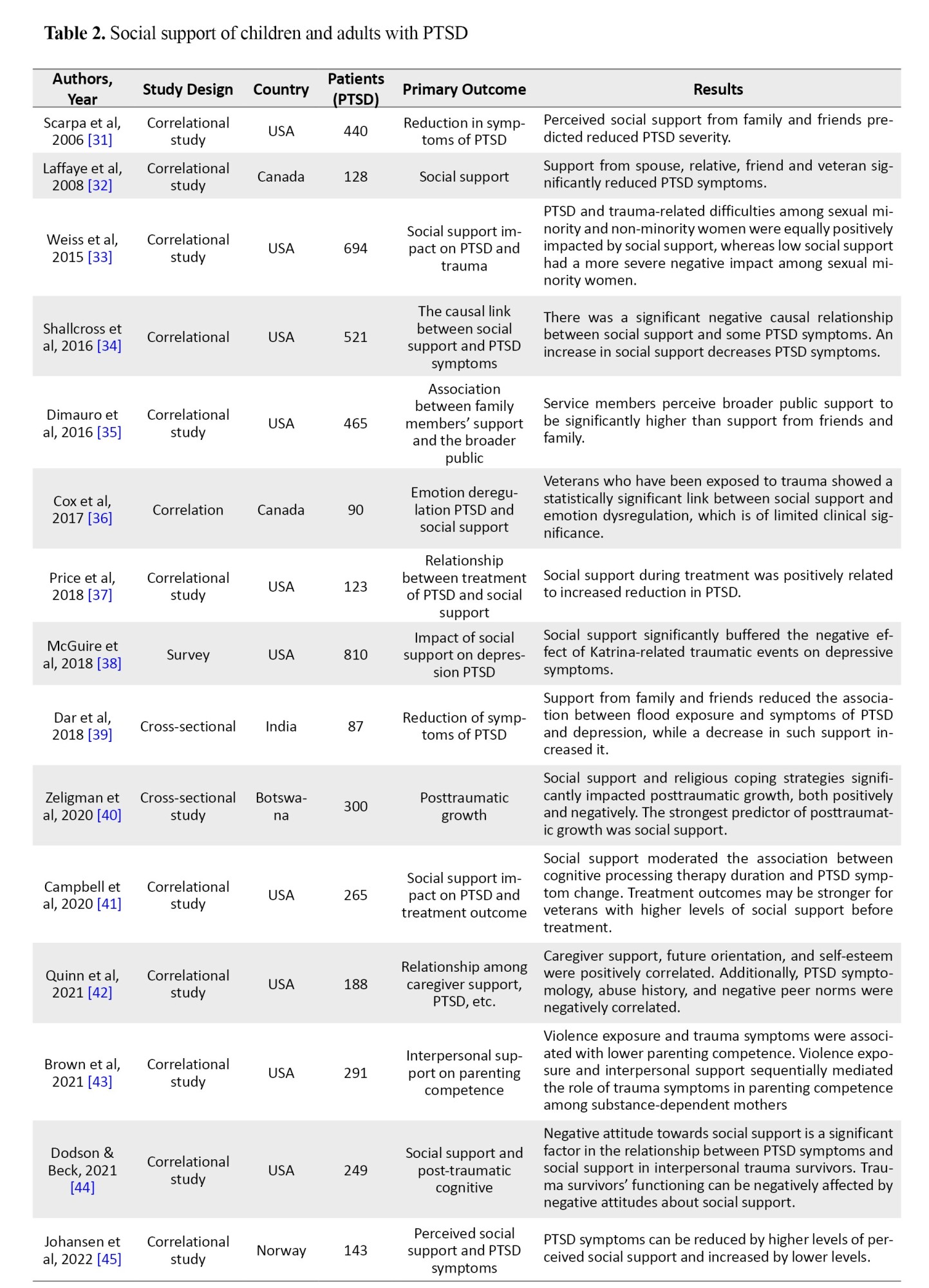

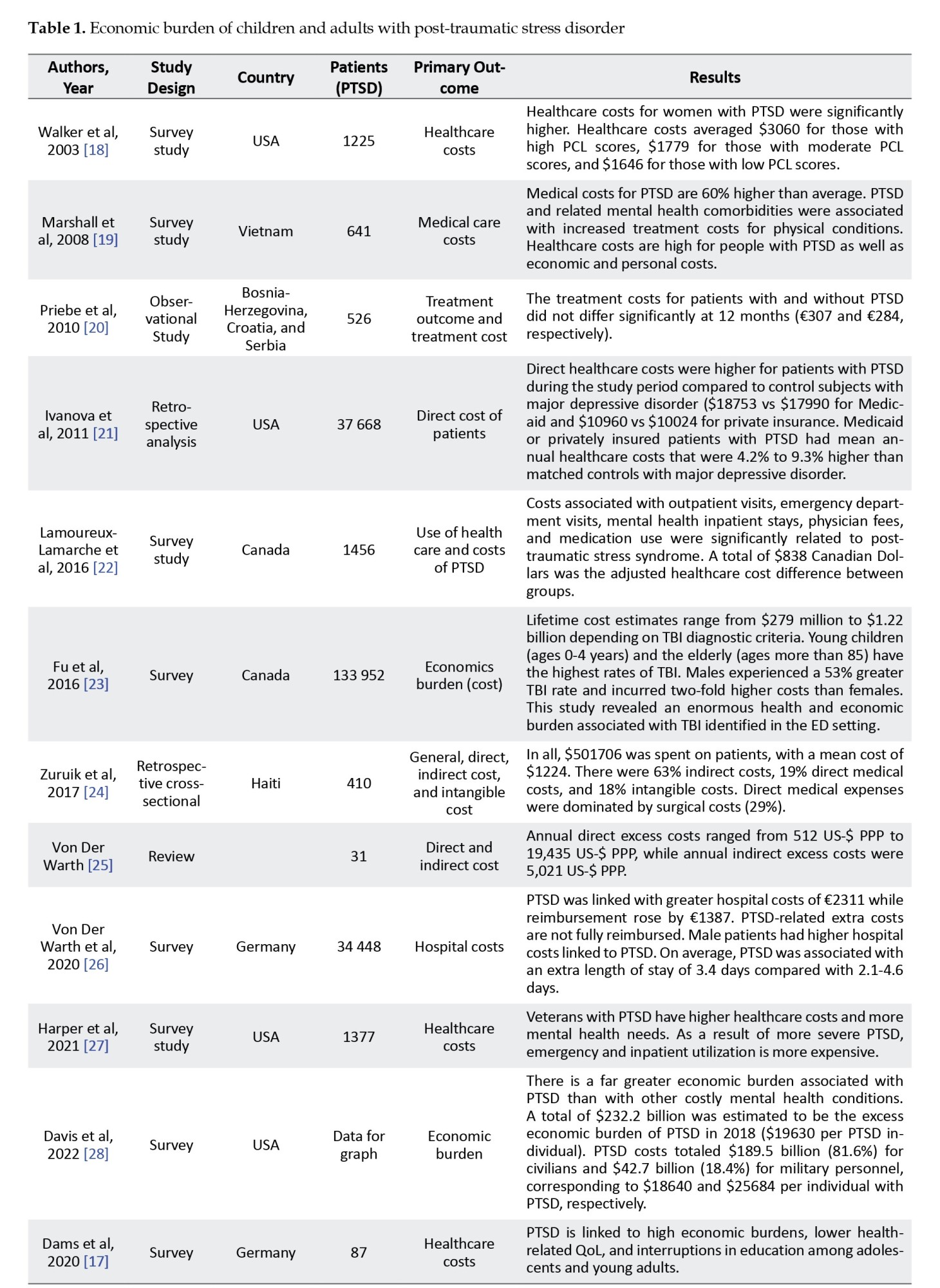

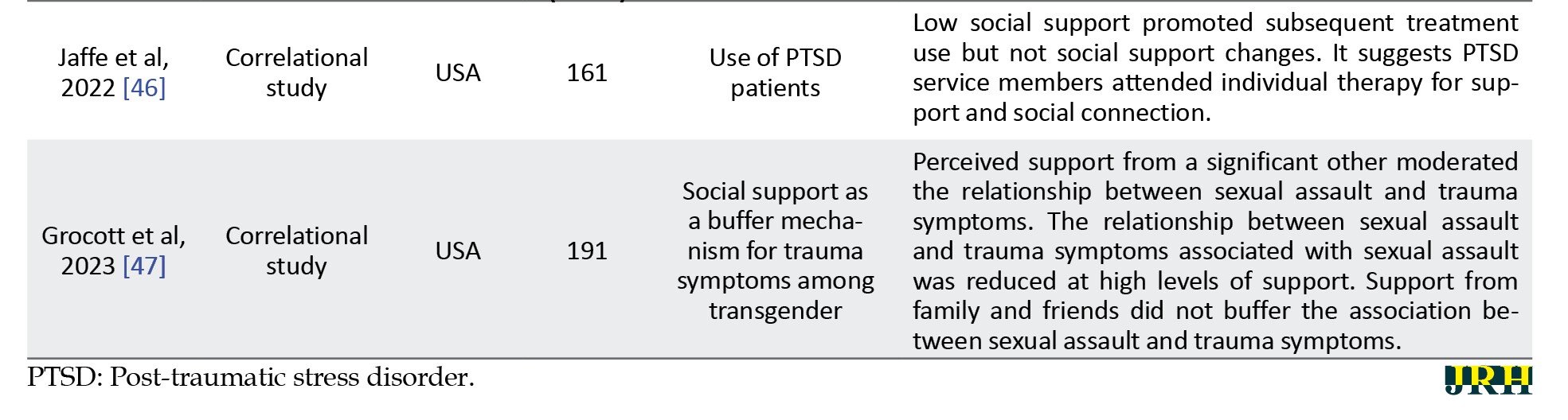

Most economic burden studies have been conducted in developed countries. According to Table 1, 35.7% of economic burden studies were conducted in the United States, 21.4% in Germany, 14.3% in Canada, 7.14% in Haiti, 7.14% in Vietnam, and 12.32% in more than one country. In addition, most of the previous studies on social support were conducted in developed countries.

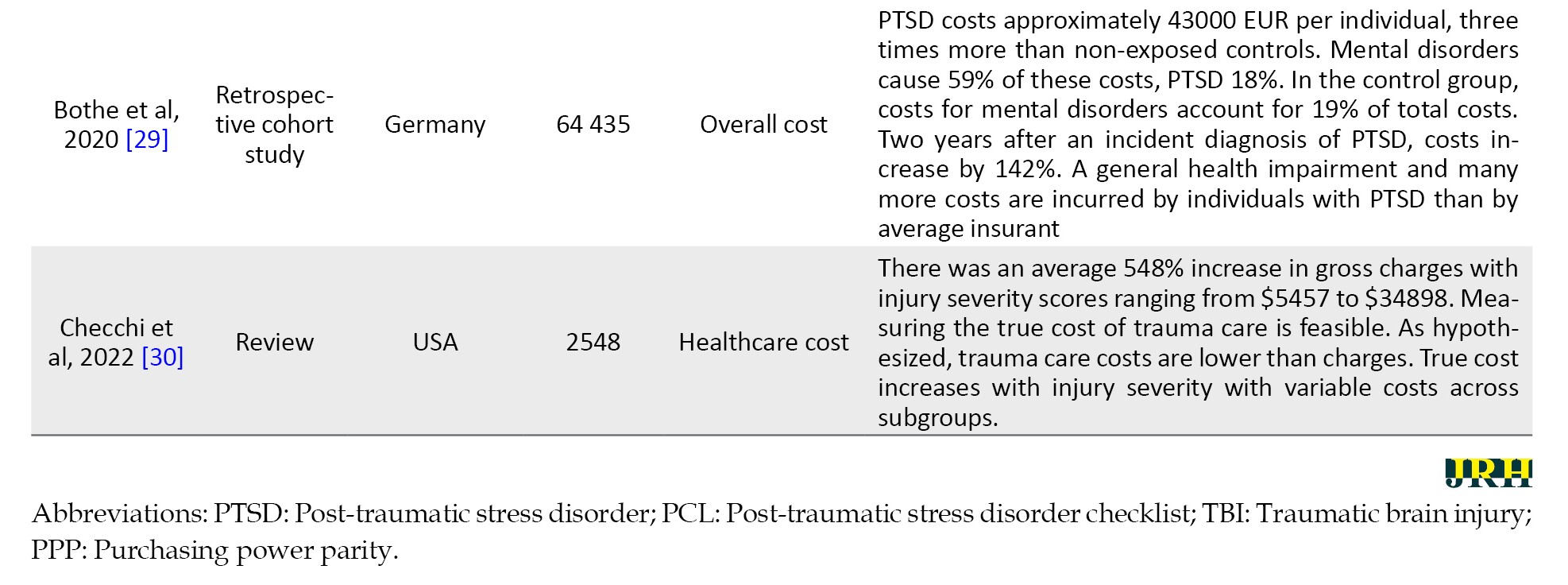

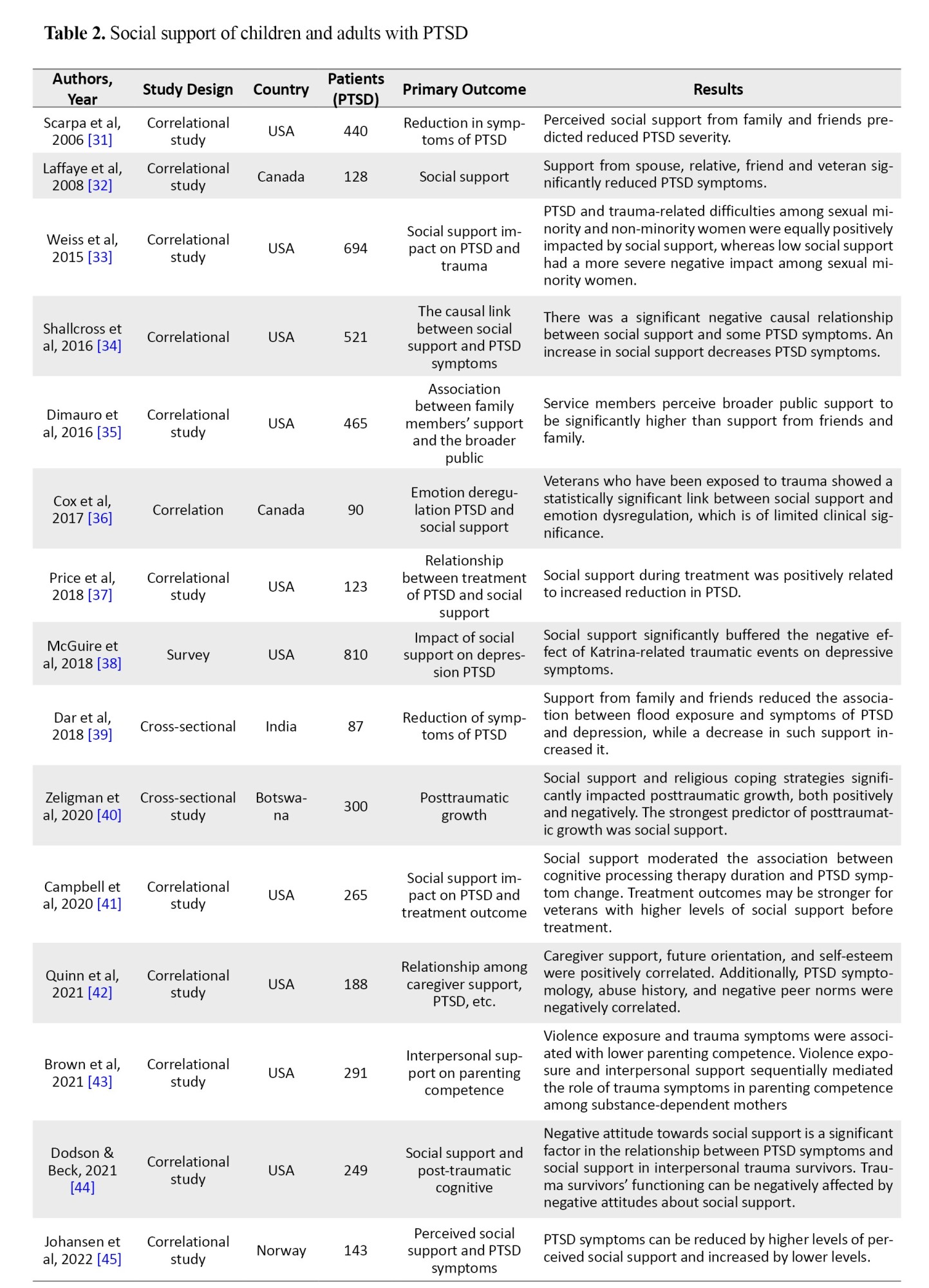

Table 2 shows that 70.5% of the studies were conducted in the United States, 11.8% in Canada, 5.9% in India, 5.9% in Botswana, and 5.9% in Norway. The predominant research designs in the economic burden literature included survey (57.1%), retrospective analysis (21.4%), review (14.3%), and observation (7.1%). In Table 2, the predominant research designs in the social support studies included correlational studies (82.4%), cross-sectional studies (11.8%), and surveys (5.9%).

Economic burdens of individuals with PTSD

The PTSD literature in Table 1 shows that individuals with PTSD face high economic burdens as the ailments disrupt their opportunities to acquire requisite skills, mental health conditions, and productivity. A study revealed that PTSD was linked to high economic burdens, lower health-related QoL, and interruptions in education among adolescents and young adults [17]. The economic burden of PTSD patients is also associated with the costs of medical care services and purchasing recommended medications.

According to most of the literature, medical care for PTSD is quite expensive compared to other mental illnesses. According to Marshall et al., the medical costs of PTSD are 60% more expensive than the average costs. These include economic and personal costs [19]. They [19] emphasized that PTSD and other mental comorbidities are associated with increased treatment costs for physical illnesses. A comparison of the direct medical costs of PTSD with other mental health problems, [21] found that the direct healthcare costs for patients with PTSD were higher than those for patients with major depressive disorder, which were 4.2% to 9.3% higher. Additionally, studies conducted among veterans showed that veterans with PTSD had higher healthcare costs and greater mental health needs because their emergency and inpatient utilization rates were higher [27]. To determine if there was a significant difference in the direct costs of patients with PTSD, a study found that the costs for patients with and without PTSD did not differ significantly at 12 months [20]. The study reported that PTSD was highly associated with annual indirect costs estimated at US $5021 per person per year [25].

Regarding the effect of gender on the cost of treating individuals with PTSD, the literature provides conflicting findings. Walker et al. found that healthcare costs for women with PTSD were significantly higher than their male counterparts [18], while Fu et al. reported that men experienced a 53% higher traumatic brain injury rate and the cost was double that of women [23]. These researchers [23] reiterated that traumatic brain injury poses an enormous health and economic burden.

Influence of social supports on individuals with PTSD

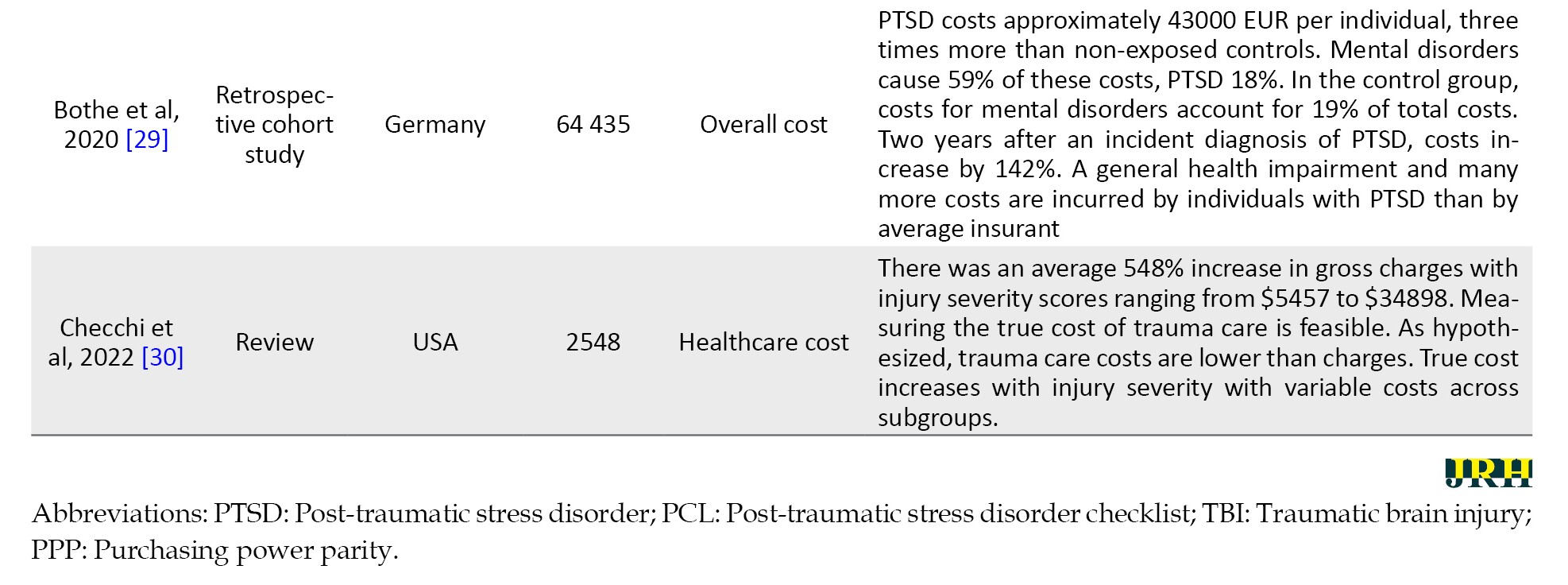

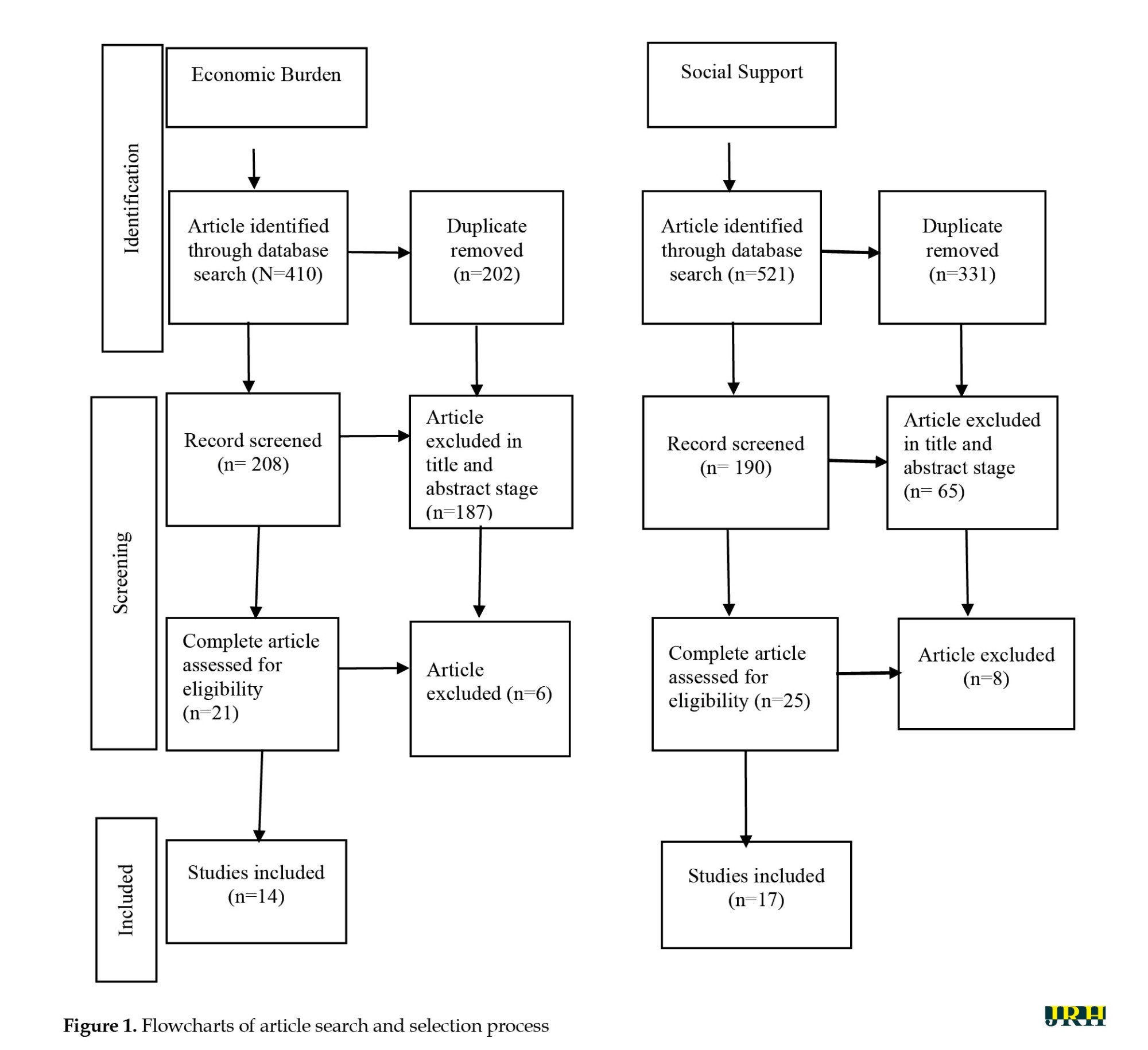

In the PTSD literature, social support has been identified as an essential factor in the management of PTSD patients. As Table 2 shows, there is considerable empirical evidence that social support plays an important role in reducing PTSD symptoms in patients. Two studies showed that the severity of PTSD was drastically reduced by perceived social support from family and friends [31, 32]. Among sexual minority and non-minority women [33], social support was reported to have positive effects on PTSD and trauma-related difficulties, while low levels of social support among sexual minority women had more severe negative effects.

Regarding the effectiveness of social support in patients with PTSD, research by Johansen et al. showed that the symptoms of PTSD are reduced by higher levels of perceived social support and enhanced by lower levels of perceived social support [45]. Furthermore, McGuire [38] reported that social support significantly buffered the negative impact of Katrina-related traumatic events on depressive symptoms. Another study conducted by Johansen [44] found that the functioning of trauma survivors was negatively impacted by negative attitudes toward social support. Individuals with PTSD who were positive about social support had a higher chance of recovering from their condition.

In addition, as shown in Table 2, a negative relationship was found between social support and PTSD. Shallcross [34] reported a significant negative causal relationship between social support and some PTSD symptoms. As a result, an increase in social support is associated with a decrease in PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, Price [37] reported that social support during treatment helped reduce PTSD symptoms. This indicates that social support is effective in increasing treatment effectiveness. Other studies have highlighted the effectiveness of various other types of social support. A study conducted by Dar [39] found that social support from family and friends reduced the association between flood exposure and symptoms of PTSD and depression, whereas a reduction in this support increased symptoms. Another study by Dimauro [35] pointed out that service members perceived public support as significantly higher than support from friends and family.

The empirical evidence in Table 2 shows the moderating effect of social support in isolation and collaboration with other factors. A study conducted by Grocott [47] revealed that perceived social support moderated the relationship between sexual assault and trauma symptoms. Another study by Campbell [41] reported that social support mediates the association between the duration of cognitive processing therapy and change in PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, Zeligman [40] found that social support and religious coping strategies significantly negatively affected posttraumatic growth.

Discussion

Economic burdens of individuals with PTSD

Based on the findings of this scoping review, PTSD represents an overwhelming economic burden for patients, caregivers, and society at large. The economic burden of PTSD includes direct medical care costs and indirect costs. The results of this study demonstrated that there are huge direct costs associated with treating PTSD symptoms [17, 48]. Direct costs of PTSD include but are not limited to, consultation charges, medicine purchase costs, treatment costs, transportation costs, emergency visit costs, and insurance coverage. The direct medical healthcare costs associated with PTSD patients are higher than those associated with other mental health problems [19-21, 27]. Accordingly, the cost of medical care related to the symptoms of PTSD is quite high and therefore places a huge economic burden on patients and caregivers.

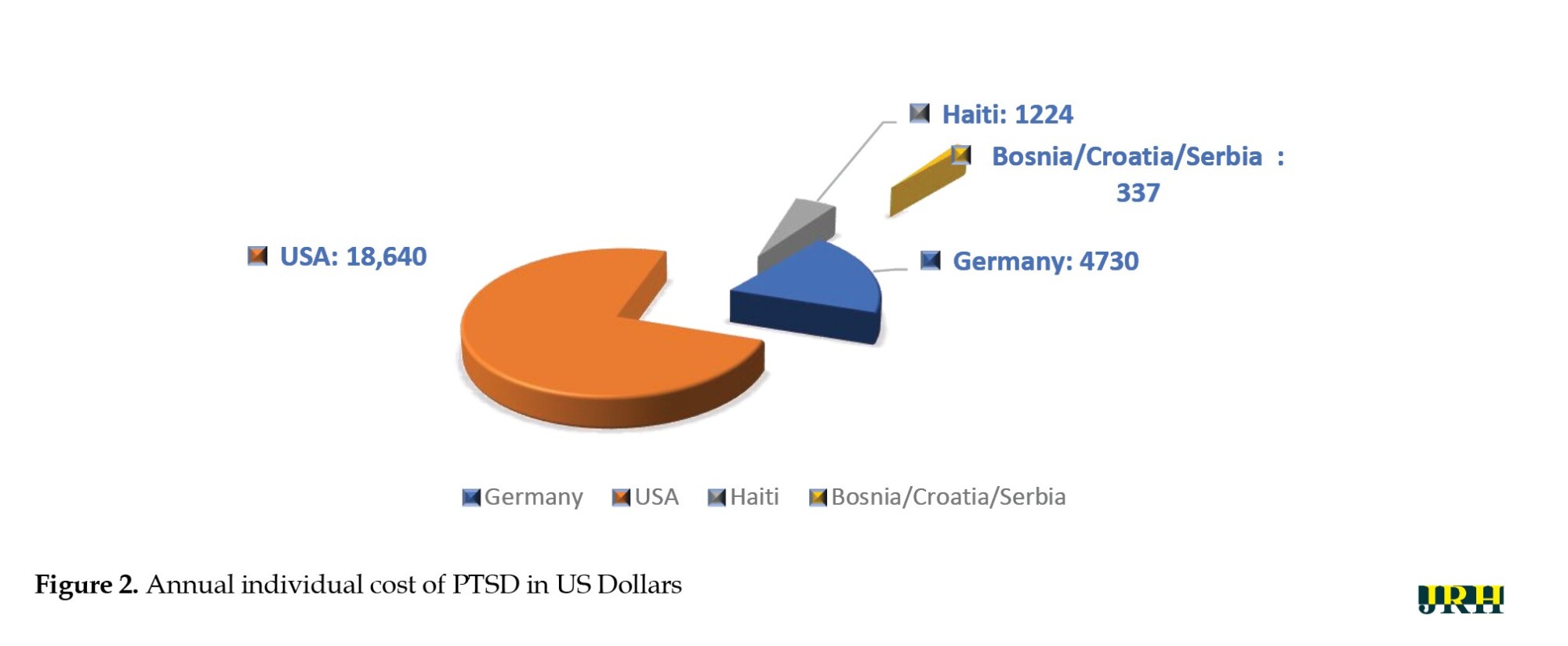

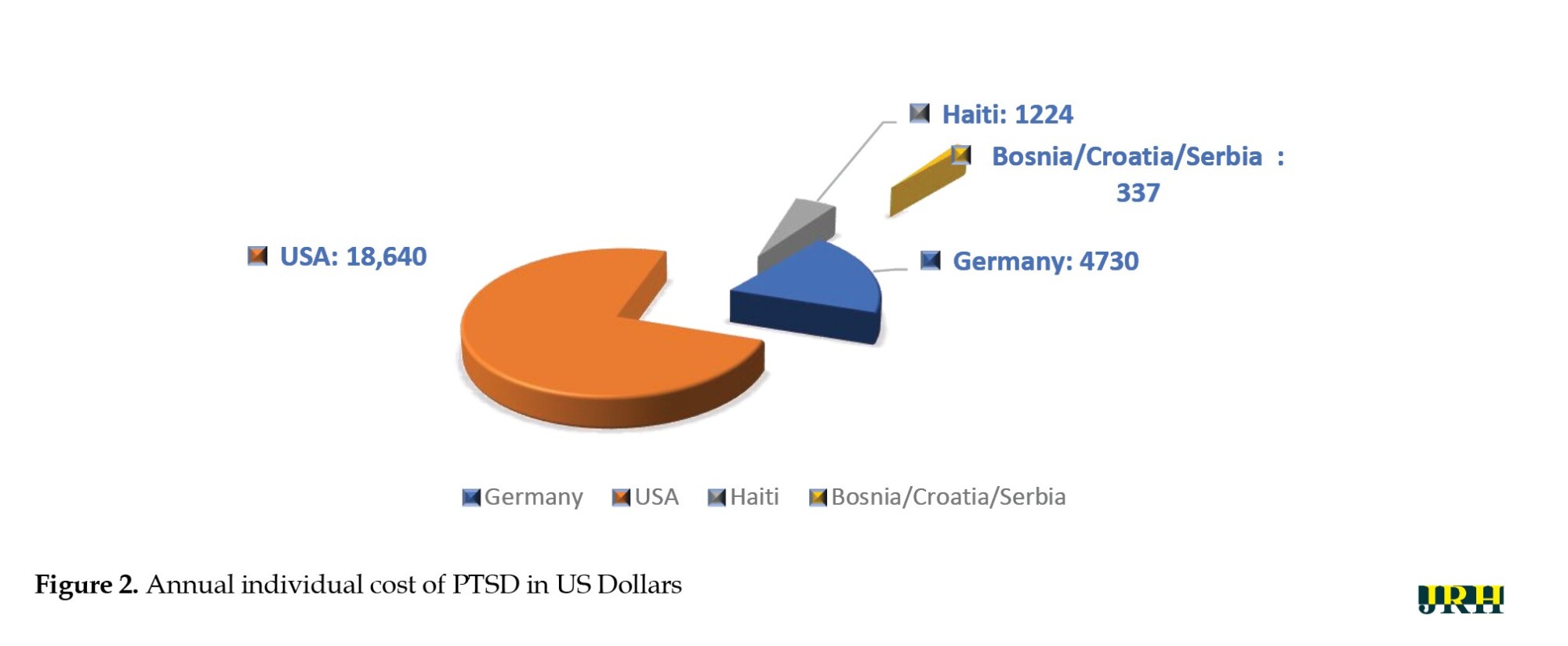

The cost of treating patients with PTSD varies greatly from country to country. Data from the empirical literature shows that the direct annual cost of healthcare for an individual in the USA is $18640, which is four to five times more than other countries (Figure 2).

PTSD patients in Germany pay US $4730 annually, which is more than three times what Haiti pays and 14 times what Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia pay. This shows that the annual cost of PTSD medical care is higher in the developed world than in developing or underdeveloped countries. The direct costs of PTSD depend on the type of medical services and the professionals involved in the treatment. The costs associated with PTSD, particularly in the US, are staggering as they depend on the type of medical and mental health symptoms that the individual or group of people has developed [9]. However, despite the manageable literature on the direct costs of PTSD, Von der Warth [25] estimated the annual indirect costs of PTSD, suggesting that there is a lack of literature on this aspect. While the indirect costs are not easy to estimate, it is important to understand their devastating impact on an economy. Therefore, more studies need to be conducted to determine the full and comprehensive economic burden of PTSD.

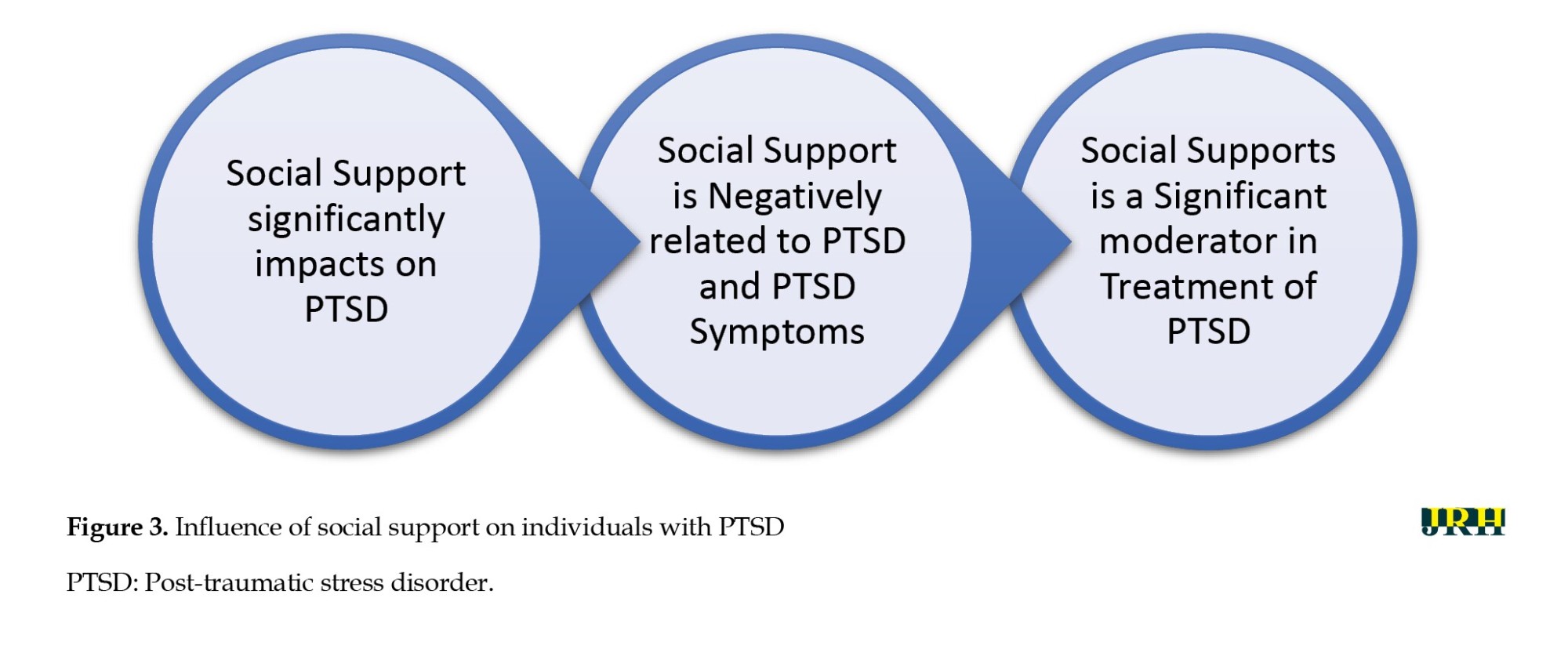

This scoping review also found that there are differences in the cost of treating male and female PTSD patients. According to Walker [18], the medical care costs of female patients are higher than those of male counterparts. A study also found that being female is one of the factors that contribute to the cost of treating people with PTSD [48]. This implies that female patients bear more direct and indirect costs due to their nature. This may be due to the severity and complexity of the condition, or a higher likelihood of developing chronic health conditions that require appropriate monitoring and medical care. In contrast to the above findings, Fu [23] reported that the cost of treating male patients with traumatic brain injury was 53% higher than their female counterparts. This is because the frequency of traumatic brain injuries is higher in men. The literature indicates that it is the leading cause of death and disability that can lead to permanent neurological complications [49]. However, variability in the costs of male and female preference remains controversial as the literature is limited, and further studies need to explore this disparity to provide sufficient evidence. Therefore, there is a high direct cost economic burden for patients with PTSD, as mentioned in this study (Figure 3).

Influence of social support on individuals with PTSD

This review found that social support plays an important role in the medical care of individuals with PTSD. Through a comprehensive scoping review approach, this study established that social support, regardless of its source, has a significant impact on individuals with PTSD [45]. It also confirmed that social support and perceived social support significantly reduced PTSD symptoms [31-33]. Hence, social support, such as public relief items, family support, and support from friends, are effective and acceptable ways to help people with PTSD recover and improve their mental health. However, the effect of social support is extremely personalized. The provider must be cognizant of the patient’s age, and culturally sensitive to prevent patients from developing negative attitudes towards social support services [44]. This is because trauma patients' recovery is impaired by negative attitudes toward social support [44].

Furthermore, this study found that social support is negatively associated with PTSD and its symptoms [44, 34]. Accordingly, there is an inverse relationship between social support and PTSD symptoms, suggesting that an increase in social support can lead to a reduction in PTSD symptoms. Social support during treatment has been shown to facilitate the speedy recovery of PTSD patients. This has also proven useful for patients undergoing psychological recovery efforts. Therefore, regardless of the timing of the social support, and provided that it does not violate the societal norms of the target group or their religious beliefs, it facilitates the recovery of the patients from PTSD symptoms.

According to the results, social support, either in isolation or in concert with other factors, is a key moderator in treating PTSD [41, 47]. In this sense, social support plays a moderating role both in the effectiveness of medical care services and in the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Social support plays a dual role in improving the mental health of people with PTSD. Therefore, social support should be aimed at people who have experienced traumatic events and who show symptoms of PTSD to curtail the potential negative effects.

Major gaps identified in the literature

This scoping review found that most of the studies were conducted in developed countries. This indicates that few studies have examined the economic burden or social support for people with PTSD in developing countries, although there is a wealth of literature on the presence of traumatic events and associated PTSD. For example, traumatic events related to war and genocides to which thousands of people have been exposed [50] and traumatic events related to human immunodeficiency virus patients occur repeatedly in Africa [51]. Another study also found a high incidence of PTSD in Ethiopia among internally displaced persons [52]. Therefore, further studies are needed in some developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of Asia to determine the economic burden of individuals with PTSD and the social support provided to facilitate their recovery.

Furthermore, most researchers in the economic burden literature have focused on the direct costs of PTSD symptoms and omitted the indirect costs. Therefore, the economic burden has only been partially represented. There was scant literature on PTSD associated with natural phenomena such as floods, wildfires, disease, viral pandemics, and ethno-religious conflicts.

Conclusion

In this scoping review, we examined the economic burdens and social support associated with PTSD patients. This study established the economic burden of PTSD across the globe. This review revealed that the economic burdens of PTSD in terms of direct personal costs vary across countries. This study underscored the significant impact of gender factors on the economic burden and social support associated with PTSD disorders. The review also found the significant impact of social support in improving the recovery of PTSD patients. Social support is inversely related to PTSD. Its effective mediating role in treating individuals with PTSD reduces its devastating effect on patients, thereby facilitating patient recovery. This study, the first of its kind to the best of our knowledge, laid the groundwork for future studies of the economic burden and social support for people with PTSD.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the use of strict methodological guidelines for conducting a scoping review when retrieving, analyzing, and synthesizing empirical data from various databases. More importantly, this study was driven by the economic burdens and social support for individuals with PTSD. This study is the first of its kind to examine the economic burden and social support for individuals with PTSD. Therefore, our study lays the foundation for future studies on this topic.

This study faced some limitations. First, there were some inherent limitations in conducting a scoping review such as providing breadth rather than depth of knowledge. This was demonstrated in this study when several databases were rigorously searched. We were accountable for assessing the relevance and summarizing the sources included in this study. Second, our primary goal in this scoping review was to identify the global economic burdens and social support for individuals with PTSD. However, when we started the literature search, we discovered that this goal would not be fully achieved due to the unavailability of studies in some parts of the world, particularly in developing countries. Finally, we reviewed articles from academic sources, and the literature search was limited to articles published in English; as a result, significant data contained in foreign articles were not considered.

Further studies need to be conducted in other foreign languages, such as French, Arabic, and Chinese, among others, especially since no empirical literature on economic burdens and social support has been reviewed. Future studies should pay more attention to the indirect costs of PTSD due to the limited literature. Future researchers should also consider using a mixed method of qualitative and scoping review to substantiate the findings from empirical data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and investigation: All authors; Data analysis and original draft preparation: Amos Nnaemeka Amedu; Supervision, review and editing: Veronica Dwarika.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This review would not have been possible without the assistance of digital librarians who assisted in formulating search terms and suggesting digital databases. Moreover, we would like to express our gratitude to our chief editor for polishing the language of this study.

References

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the outcome of a mental disorder that arises from exposure of a person to devastating traumatic events, such as floods, wildfires, war, and severe assaults among others [1, 2]. An individual may be exposed directly or indirectly to traumatic events through experiencing the phenomenon, observing the experiences of others, or being regularly confronted with aversive details of such events [3]. It is estimated that more than 70% of adults worldwide have experienced at least one potentially devastating incident in their lifetime [4]. Therefore, direct or indirect exposure to traumatic events is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of PTSD, which is also associated with other forms of mental illness [5, 6]. According to the PTSD literature, 5.6% of individuals who have experienced trauma develop PTSD in their lifetime [7, 8] and this is particularly evident in individuals whose disposition is characterized by avoidance, severe anxiety, nightmares, flashbacks, etc. recurring dreams about the events, and negative changes in cognition. Therefore, due to the complexity of PTSD, its treatment is considered costly [9]. This implies that individuals with PTSD could experience a substantial economic burden.

Patients with PTSD face an economic burden that goes beyond direct healthcare costs and those associated with other mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety [9]. This means that the economic burden of PTSD on society includes the indirect costs resulting from poor productivity, disability payments, reduced quality of life (QoL), and increased burden on caregivers [10]. Data from the United States indicate that PTSD has an annual economic burden of $232 billion [9]. Accordingly, PTSD is a major psychological problem that needs serious attention. The recent COVID-19 state of emergency, civil unrest, and recurring national disasters are increasing the growing pressure on PTSD and its impact on the world population [9]. As a result, the prevalence of PTSD tends to increase at the same time as the economic burden increases. Because of this, patients with PTSD need social support to further their recovery.

Social support is an important social resource that can facilitate a person’s recovery from acute adverse stress events [11]. Various sources of social support are identified in the literature, including family, friends, non-governmental organizations, and the government. According to previous studies, providing timely social support can have a significant impact on how individuals cope with recovery from PTSD [11, 12]. The conceptualization of social support has been based on how it is perceived to be multifaceted and interactional. The effectiveness of social support depends more on recipients’ perceptions rather than the perception of its providers [13]. The multifactorial conception of social support provides more information on how a particular response of an individual or a society might affect an individual’s PTSD and how the different types of social support may interact [13]. The types of social support based on diverse views include positive support, negative support, and no support at all. Positive support includes tangible aid, emotional help, and informational support, while negative support is characterized by blame, disbelief, taking control of the recipients’ choices, and withdrawal from the support recipient. No support indicates the absence of positive and negative support. Positive support improves a person’s ability to recover quickly from trauma, while negative support may suppress a person’s natural coping mechanisms.

Therefore, conducting a scoping review to determine the global economic burden of PTSD is important for policymakers, as it informs them of its prevalence and devastating impact and allows them to prioritize the allocation of resources to minimize these impacts on individuals and society. Therefore, the literature needs to be reviewed to provide an overview of the latest empirical evidence regarding the economic burdens and social support for people with PTSD. This study demonstrates the economic burdens associated with PTSD and the social support provided to promote recovery for individuals with PTSD. We are hopeful that our findings will provide policymakers, educators, therapists, and governmental and non-governmental organizations with reliable and timely evidence of the economic burdens and the social support needed for people living with PTSD. We also believe that our findings will fill the gap in the current literature on various studies on economic burdens and social support related to PTSD patients.

Review questions

The research questions that guided the current study are as follows:

What economic burdens are associated with people with PTSD?

What social support is provided to promote recovery for people with PTSD?

Methods

A preliminary search was carried out for a scoping review on the economic burden of children and adults with PTSD and associated social supports for enhancing individual recovery from PTSD in several online databases, such as Google Scholars, PubMed, Wiley Online Library, Science Direct, Springer Nature, Frontier, Scopus, APA, PTSDpubs, National Library of Medicine, the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, and JBI Evidence synthesis. No existing studies concerning a scoping review on this topic were identified. The guideline for preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis was adopted in this study [14]. This study was conducted following JBL methodological guidance [15]. It ensures the appropriateness of the scoping review in terms of data extraction, analysis, presentation, and clarification of the implications for practical research.

Literature search

We conducted an extensive literature search in several electronic databases and other journal databases, such as Scopus, APA, National Library of Medicine, Wiley Online Library, Science Direct, PTSDpubs, Frontier, Google Scholars, Elsevier. Keywords and search terms were formulated by the research team with the help of an experienced digital librarian. We used the following keywords and terms to search the database which included “economic burden of PTSD patients,” “cost of PTSD,” “financial burden of PTSD,” “financial constraints of individuals with PTSD,” “health care cost of PTSD,” and “medical cost of PTSD.” Concerning social support, the search terms used were “assistance for patients with PTSD,” “social aid for PTSD,” “social relief for PTSD,” “social welfare for PTSD,” “support services for PTSD,” “social care for individuals with PTSD,” and “community services for PTSD.” We limited our search to the period from 2000 to 2023. The date limit was used to search databases that did not have a controlled vocabulary or thesaurus. The reference list of related articles was also explored.

Eligibility of studies

Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals were analyzed. Based on the research questions formulated to guide the study, intervention studies and historical studies on the economic burden and social support of PTSD patients were excluded. Quantitative studies on the economic burden and social support of PTSD patients were included in the study. We also included reviews that captured either the economic burden or the social support of PTSD patients. A book of abstract articles was also included in the review to facilitate uniformity in reporting published articles. Opinion papers and commentaries were excluded from the review. Non-English language articles were excluded. All participants were included in this study, regardless of their age; therefore, no age restrictions were imposed. This allowed the researchers to assess the broad literature and identify the knowledge gap.

Data extraction

The data extraction was carried out by the first author (AN). The rationale for extracting the data points and the sources of the article were checked by the second author (DV). Both authors reached a consensus regarding the resolution of ambiguous data points. Three types of data were collected from selected articles. First, data was collected based on the empirical features of the reviewed articles (year of publication, first author, design, country, population, primary outcome, and result). In addition, data on economic burdens were extracted and categorized into direct cost, indirect cost, and annual cost. In addition, data comparing the economic burdens of males and females was extracted. All monetary values were converted and presented in US dollars using the purchasing power parity index [16]. Third, social support data were extracted and organized according to the relationship between social support and PTSD symptoms, the effectiveness of social support for individuals with PTSD, and the mediating roles of social support.

Results

Study selection

This study identified 410 articles on economic burdens and 521 articles on social support through a comprehensive search of academic databases. These articles underwent a double filtering that removed 202 articles from the economic burden literature and 331 articles from the social support. The remaining 208 and 190 articles on economic burden and social support, respectively, were further screened for title and abstract suitability. At this point, 187 articles were removed from the economic burden literature and 165 articles from the social support literature. Finally, 14 articles were assessed for their economic burden and 17 articles for their social support (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

Most economic burden studies have been conducted in developed countries. According to Table 1, 35.7% of economic burden studies were conducted in the United States, 21.4% in Germany, 14.3% in Canada, 7.14% in Haiti, 7.14% in Vietnam, and 12.32% in more than one country. In addition, most of the previous studies on social support were conducted in developed countries.

Table 2 shows that 70.5% of the studies were conducted in the United States, 11.8% in Canada, 5.9% in India, 5.9% in Botswana, and 5.9% in Norway. The predominant research designs in the economic burden literature included survey (57.1%), retrospective analysis (21.4%), review (14.3%), and observation (7.1%). In Table 2, the predominant research designs in the social support studies included correlational studies (82.4%), cross-sectional studies (11.8%), and surveys (5.9%).

Economic burdens of individuals with PTSD

The PTSD literature in Table 1 shows that individuals with PTSD face high economic burdens as the ailments disrupt their opportunities to acquire requisite skills, mental health conditions, and productivity. A study revealed that PTSD was linked to high economic burdens, lower health-related QoL, and interruptions in education among adolescents and young adults [17]. The economic burden of PTSD patients is also associated with the costs of medical care services and purchasing recommended medications.

According to most of the literature, medical care for PTSD is quite expensive compared to other mental illnesses. According to Marshall et al., the medical costs of PTSD are 60% more expensive than the average costs. These include economic and personal costs [19]. They [19] emphasized that PTSD and other mental comorbidities are associated with increased treatment costs for physical illnesses. A comparison of the direct medical costs of PTSD with other mental health problems, [21] found that the direct healthcare costs for patients with PTSD were higher than those for patients with major depressive disorder, which were 4.2% to 9.3% higher. Additionally, studies conducted among veterans showed that veterans with PTSD had higher healthcare costs and greater mental health needs because their emergency and inpatient utilization rates were higher [27]. To determine if there was a significant difference in the direct costs of patients with PTSD, a study found that the costs for patients with and without PTSD did not differ significantly at 12 months [20]. The study reported that PTSD was highly associated with annual indirect costs estimated at US $5021 per person per year [25].

Regarding the effect of gender on the cost of treating individuals with PTSD, the literature provides conflicting findings. Walker et al. found that healthcare costs for women with PTSD were significantly higher than their male counterparts [18], while Fu et al. reported that men experienced a 53% higher traumatic brain injury rate and the cost was double that of women [23]. These researchers [23] reiterated that traumatic brain injury poses an enormous health and economic burden.

Influence of social supports on individuals with PTSD

In the PTSD literature, social support has been identified as an essential factor in the management of PTSD patients. As Table 2 shows, there is considerable empirical evidence that social support plays an important role in reducing PTSD symptoms in patients. Two studies showed that the severity of PTSD was drastically reduced by perceived social support from family and friends [31, 32]. Among sexual minority and non-minority women [33], social support was reported to have positive effects on PTSD and trauma-related difficulties, while low levels of social support among sexual minority women had more severe negative effects.

Regarding the effectiveness of social support in patients with PTSD, research by Johansen et al. showed that the symptoms of PTSD are reduced by higher levels of perceived social support and enhanced by lower levels of perceived social support [45]. Furthermore, McGuire [38] reported that social support significantly buffered the negative impact of Katrina-related traumatic events on depressive symptoms. Another study conducted by Johansen [44] found that the functioning of trauma survivors was negatively impacted by negative attitudes toward social support. Individuals with PTSD who were positive about social support had a higher chance of recovering from their condition.

In addition, as shown in Table 2, a negative relationship was found between social support and PTSD. Shallcross [34] reported a significant negative causal relationship between social support and some PTSD symptoms. As a result, an increase in social support is associated with a decrease in PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, Price [37] reported that social support during treatment helped reduce PTSD symptoms. This indicates that social support is effective in increasing treatment effectiveness. Other studies have highlighted the effectiveness of various other types of social support. A study conducted by Dar [39] found that social support from family and friends reduced the association between flood exposure and symptoms of PTSD and depression, whereas a reduction in this support increased symptoms. Another study by Dimauro [35] pointed out that service members perceived public support as significantly higher than support from friends and family.

The empirical evidence in Table 2 shows the moderating effect of social support in isolation and collaboration with other factors. A study conducted by Grocott [47] revealed that perceived social support moderated the relationship between sexual assault and trauma symptoms. Another study by Campbell [41] reported that social support mediates the association between the duration of cognitive processing therapy and change in PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, Zeligman [40] found that social support and religious coping strategies significantly negatively affected posttraumatic growth.

Discussion

Economic burdens of individuals with PTSD

Based on the findings of this scoping review, PTSD represents an overwhelming economic burden for patients, caregivers, and society at large. The economic burden of PTSD includes direct medical care costs and indirect costs. The results of this study demonstrated that there are huge direct costs associated with treating PTSD symptoms [17, 48]. Direct costs of PTSD include but are not limited to, consultation charges, medicine purchase costs, treatment costs, transportation costs, emergency visit costs, and insurance coverage. The direct medical healthcare costs associated with PTSD patients are higher than those associated with other mental health problems [19-21, 27]. Accordingly, the cost of medical care related to the symptoms of PTSD is quite high and therefore places a huge economic burden on patients and caregivers.

The cost of treating patients with PTSD varies greatly from country to country. Data from the empirical literature shows that the direct annual cost of healthcare for an individual in the USA is $18640, which is four to five times more than other countries (Figure 2).

PTSD patients in Germany pay US $4730 annually, which is more than three times what Haiti pays and 14 times what Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia pay. This shows that the annual cost of PTSD medical care is higher in the developed world than in developing or underdeveloped countries. The direct costs of PTSD depend on the type of medical services and the professionals involved in the treatment. The costs associated with PTSD, particularly in the US, are staggering as they depend on the type of medical and mental health symptoms that the individual or group of people has developed [9]. However, despite the manageable literature on the direct costs of PTSD, Von der Warth [25] estimated the annual indirect costs of PTSD, suggesting that there is a lack of literature on this aspect. While the indirect costs are not easy to estimate, it is important to understand their devastating impact on an economy. Therefore, more studies need to be conducted to determine the full and comprehensive economic burden of PTSD.

This scoping review also found that there are differences in the cost of treating male and female PTSD patients. According to Walker [18], the medical care costs of female patients are higher than those of male counterparts. A study also found that being female is one of the factors that contribute to the cost of treating people with PTSD [48]. This implies that female patients bear more direct and indirect costs due to their nature. This may be due to the severity and complexity of the condition, or a higher likelihood of developing chronic health conditions that require appropriate monitoring and medical care. In contrast to the above findings, Fu [23] reported that the cost of treating male patients with traumatic brain injury was 53% higher than their female counterparts. This is because the frequency of traumatic brain injuries is higher in men. The literature indicates that it is the leading cause of death and disability that can lead to permanent neurological complications [49]. However, variability in the costs of male and female preference remains controversial as the literature is limited, and further studies need to explore this disparity to provide sufficient evidence. Therefore, there is a high direct cost economic burden for patients with PTSD, as mentioned in this study (Figure 3).

Influence of social support on individuals with PTSD

This review found that social support plays an important role in the medical care of individuals with PTSD. Through a comprehensive scoping review approach, this study established that social support, regardless of its source, has a significant impact on individuals with PTSD [45]. It also confirmed that social support and perceived social support significantly reduced PTSD symptoms [31-33]. Hence, social support, such as public relief items, family support, and support from friends, are effective and acceptable ways to help people with PTSD recover and improve their mental health. However, the effect of social support is extremely personalized. The provider must be cognizant of the patient’s age, and culturally sensitive to prevent patients from developing negative attitudes towards social support services [44]. This is because trauma patients' recovery is impaired by negative attitudes toward social support [44].

Furthermore, this study found that social support is negatively associated with PTSD and its symptoms [44, 34]. Accordingly, there is an inverse relationship between social support and PTSD symptoms, suggesting that an increase in social support can lead to a reduction in PTSD symptoms. Social support during treatment has been shown to facilitate the speedy recovery of PTSD patients. This has also proven useful for patients undergoing psychological recovery efforts. Therefore, regardless of the timing of the social support, and provided that it does not violate the societal norms of the target group or their religious beliefs, it facilitates the recovery of the patients from PTSD symptoms.

According to the results, social support, either in isolation or in concert with other factors, is a key moderator in treating PTSD [41, 47]. In this sense, social support plays a moderating role both in the effectiveness of medical care services and in the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Social support plays a dual role in improving the mental health of people with PTSD. Therefore, social support should be aimed at people who have experienced traumatic events and who show symptoms of PTSD to curtail the potential negative effects.

Major gaps identified in the literature

This scoping review found that most of the studies were conducted in developed countries. This indicates that few studies have examined the economic burden or social support for people with PTSD in developing countries, although there is a wealth of literature on the presence of traumatic events and associated PTSD. For example, traumatic events related to war and genocides to which thousands of people have been exposed [50] and traumatic events related to human immunodeficiency virus patients occur repeatedly in Africa [51]. Another study also found a high incidence of PTSD in Ethiopia among internally displaced persons [52]. Therefore, further studies are needed in some developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of Asia to determine the economic burden of individuals with PTSD and the social support provided to facilitate their recovery.

Furthermore, most researchers in the economic burden literature have focused on the direct costs of PTSD symptoms and omitted the indirect costs. Therefore, the economic burden has only been partially represented. There was scant literature on PTSD associated with natural phenomena such as floods, wildfires, disease, viral pandemics, and ethno-religious conflicts.

Conclusion

In this scoping review, we examined the economic burdens and social support associated with PTSD patients. This study established the economic burden of PTSD across the globe. This review revealed that the economic burdens of PTSD in terms of direct personal costs vary across countries. This study underscored the significant impact of gender factors on the economic burden and social support associated with PTSD disorders. The review also found the significant impact of social support in improving the recovery of PTSD patients. Social support is inversely related to PTSD. Its effective mediating role in treating individuals with PTSD reduces its devastating effect on patients, thereby facilitating patient recovery. This study, the first of its kind to the best of our knowledge, laid the groundwork for future studies of the economic burden and social support for people with PTSD.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the use of strict methodological guidelines for conducting a scoping review when retrieving, analyzing, and synthesizing empirical data from various databases. More importantly, this study was driven by the economic burdens and social support for individuals with PTSD. This study is the first of its kind to examine the economic burden and social support for individuals with PTSD. Therefore, our study lays the foundation for future studies on this topic.

This study faced some limitations. First, there were some inherent limitations in conducting a scoping review such as providing breadth rather than depth of knowledge. This was demonstrated in this study when several databases were rigorously searched. We were accountable for assessing the relevance and summarizing the sources included in this study. Second, our primary goal in this scoping review was to identify the global economic burdens and social support for individuals with PTSD. However, when we started the literature search, we discovered that this goal would not be fully achieved due to the unavailability of studies in some parts of the world, particularly in developing countries. Finally, we reviewed articles from academic sources, and the literature search was limited to articles published in English; as a result, significant data contained in foreign articles were not considered.

Further studies need to be conducted in other foreign languages, such as French, Arabic, and Chinese, among others, especially since no empirical literature on economic burdens and social support has been reviewed. Future studies should pay more attention to the indirect costs of PTSD due to the limited literature. Future researchers should also consider using a mixed method of qualitative and scoping review to substantiate the findings from empirical data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and investigation: All authors; Data analysis and original draft preparation: Amos Nnaemeka Amedu; Supervision, review and editing: Veronica Dwarika.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This review would not have been possible without the assistance of digital librarians who assisted in formulating search terms and suggesting digital databases. Moreover, we would like to express our gratitude to our chief editor for polishing the language of this study.

References

- Al Jowf GI, Ahmed ZT, An N, Reijnders RA, Ambrosino E, Rutten BPF, et al. A public health perspective of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6474. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19116474] [PMID]

- Nilaweera D, Phyo AZZ, Teshale AB, Htun HL, Wrigglesworth J, Gurvich C, et al. Lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder as a predictor of mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2023; 23(1):229. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-023-04716-w] [PMID]

- Widiger TA, Costa, PT. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2013. [Link]

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine. 2016; 46(2):327-43. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291715001981] [PMID]

- Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Demmer RT, Cerdá M, Koenen KC, Uddin M, et al. Potentially traumatic events and the risk of six physical health conditions in a population-based sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2013; 30(5):451-60. [DOI:10.1002/da.22090] [PMID]

- Scott KM, Koenen KC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, et al. Associations between lifetime traumatic events and subsequent chronic physical conditions: A cross-national, cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2013; 8(11):e80573. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0080573] [PMID]

- Moreira AL, Van Meter A, Genzlinger J, Youngstrom EA. Review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of adult bipolar disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017; 78(9):11720. [Link]

- Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin KA, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine. 2017; 47(13):2260-74. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291717000708] [PMID]

- Richman M. Study: Economic burden of PTSD ‘staggering [internet]. 2022. [Updated June 2024]. Available from: [Link]

- Ferry FR, Brady SE, Bunting BP, Murphy SD, Bolton D, O’Neill SM. The economic burden of PTSD in Northern Ireland. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015; 28(3):191-7. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22008] [PMID]

- Braun-Lewensohn O. Coping and social support in children exposed to mass trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2015; 17(6):46. [DOI:10.1007/s11920-015-0576-y] [PMID]

- Masten AS, Narayan AJ. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012; 63:227-57. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100356] [PMID]

- Pruitt LD, Zoellner LA. The impact of social support: An analogue investigation of the aftermath of trauma exposure. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008; 22(2):253-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.005] [PMID]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018; 169(7):467-73. [DOI:10.7326/M18-0850] [PMID]

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2020; 18(10):2119-26. [DOI:10.11124/JBIES-20-00167] [PMID]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Earnings and wages - average wages [internet]. 2014. [Updated June 2014]. Available from: [Link]

- Dams J, Rimane E, Steil R, Renneberg B, Rosner R, König HH. Health-related quality of life and costs of posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents and young adults in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020; 11:697. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00697] [PMID]

- Walker EA, Katon W, Russo J, Ciechanowski P, Newman E, Wagner AW. Health care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003; 60(4):369-74. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.369] [PMID]

- Marshall RP, Jorm AF, Grayson DA, O’Toole BI. Medical-care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000; 34(6):954-62. [DOI:10.1080/000486700269]

- Priebe S, Gavrilovic JJ, Matanov A, Franciskovic T, Knezevic G, Ljubotina D, et al. Treatment outcomes and costs at specialized centers for the treatment of PTSD after the war in former Yugoslavia. Psychiatric Services. 2010; 61(6):598-604.[DOI:10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.598] [PMID]

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Chen L, Duhig AM, Dayoub EJ, Kantor ES, et al. Cost of post-traumatic stress disorder vs major depressive disorder among patients covered by medicaid or private insurance. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2011; 17(8):e314-23. [PMID]

- Lamoureux-Lamarche C, Vasiliadis HM, Préville M, Berbiche D. Healthcare use and costs associated with post-traumatic stress syndrome in a community sample of older adults: Results from the ESA-Services study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2016; 28(6):903-11. [DOI:10.1017/S1041610215001775] [PMID]

- Fu TS, Jing R, McFaull SR, Cusimano MD. Health &economic burden of traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2016; 43(2):238-47. [DOI:10.1017/cjn.2015.320] [PMID]

- Zuraik C, Sampalis J, Brierre A. The economic and social burden of traumatic injuries: Evidence from a trauma hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. World Journal of Surgery. 2018; 42(6):1639-46. [DOI:10.1007/s00268-017-4360-5] [PMID]

- von der Warth R, Dams J, Grochtdreis T, König HH. Economic evaluations and cost analyses in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2020; 11(1):1753940. [DOI:10.1080/20008198.2020.1753940] [PMID]

- von der Warth R, Hehn P, Wolff J, Kaier K. Hospital costs associated with post-traumatic stress disorder in somatic patients: A retrospective study. Health Economics Review. 2020; 10(1):23. [DOI:10.1186/s13561-020-00281-0] [PMID]

- Harper KL, Moshier S, Ellickson-Larew S, Andersen MS, Wisco BE, Mahoney CT, et al. A prospective examination of health care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder diagnostic status and symptom severity among veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2022; 35(2):671-81. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22785] [PMID]

- Davis LL, Schein J, Cloutier M, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Maitland J, Urganus A, et al. The economic burden of posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2022; 83(3):21m14116. [PMID]

- Bothe T, Jacob J, Kröger C, Walker J. How expensive are post-traumatic stress disorders? Estimating incremental health care and economic costs on anonymised claims data. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2020; 21(6):917-30. [DOI:10.1007/s10198-020-01184-x] [PMID]

- Checchi KD, Goljan C, Rooney AS, Calvo RY, Benham DA, Prieto JM, et al. Why trauma care is not expensive: detailed analysis of actual costs and cost differences of patient cohorts. The American Surgeon. 2022; 88(10):2440-4. [DOI:10.1177/00031348221101484] [PMID]

- Scarpa A, Haden SC, Hurley J. Community violence victimization and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006; 21(4):446-69.[DOI:10.1177/0886260505285726] [PMID]

- Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, Rosen C. Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008; 21(4):394-401. [DOI:10.1002/jts.20348] [PMID]

- Weiss BJ, Garvert DW, Cloitre M. PTSD and trauma-related difficulties in sexual minority women: The impact of perceived social support. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015; 28(6):563-71. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22061] [PMID]

- Shallcross SL, Arbisi PA, Polusny MA, Kramer MD, Erbes CR. Social causation versus social erosion: Comparisons of causal models for relations between support and PTSD symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2016; 29(2):167-75. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22086] [PMID]

- DiMauro J, Renshaw KD, Smith BN, Vogt D. Perceived support from multiple sources: Associations with PTSD symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2016; 29(4):332-9. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22114] [PMID]

- Cox DW, Bakker AM, Naifeh JA. Emotion dysregulation and social support in PTSD and depression: A study of trauma-exposed veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2017; 30(5):545-9. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22226] [PMID]

- Price M, Lancaster CL, Gros DF, Legrand AC, van Stolk-Cooke K, Acierno R. An examination of social support and PTSD treatment response during prolonged exposure. Psychiatry. 2018; 81(3):258-70. [DOI:10.1080/00332747.2017.1402569] [PMID]

- McGuire AP, Gauthier JM, Anderson LM, Hollingsworth DW, Tracy M, Galea S, et al. Social support moderates effects of natural disaster exposure on depression and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: Effects for displaced and nondisplaced residents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2018; 31(2):223-33. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22270] [PMID]

- Dar KA, Iqbal N, Prakash A, Paul MA. PTSD and depression in adult survivors of flood fury in Kashmir: The payoffs of social support. Psychiatry Research. 2018; 261:449-55. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.023] [PMID]

- Zeligman M, Majuta AR, Shannonhouse LR. Posttraumatic growth in prolonged drought survivors in Botswana: The role of social support and religious coping. Traumatology. 2020; 26(3):308-16. [DOI:10.1037/trm0000237]

- Campbell SB, Erbes C, Grubbs K, Fortney J. Social support moderates the association between posttraumatic stress disorder treatment duration and treatment outcomes in telemedicine-based treatment among rural veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2020; 33(4):391-400. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22542] [PMID]

- Quinn CR, Boyd DT, Kim B-KE, Menon SE, Logan-Greene P, Asemota E, et al. The influence of familial and peer social support on post-traumatic stress disorder among black girls in juvenile correctional facilities. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2021; 48(7):867-83. [DOI:10.1177/0093854820972731]

- Brown S, Resko S, Dayton CJ, Barron C. Trauma symptoms and social support mediate the impact of violence exposure on parenting competence among substance-dependent mothers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021; 36(9-10):4570-92. [DOI:10.1177/0886260518791234] [PMID]

- Dodson TS, Beck JG. Using social support matter in the association of post-traumatic cognitions and perceived social support? Comparison of female survivors of intimate partner violence with and without a history of child abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021; 36(21-22):NP11674-NP11694.[DOI:10.1177/0886260519888529] [PMID]

- Johansen VA, Milde AM, Nilsen RM, Breivik K, Nordanger DØ, Stormark KM, et al. The relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms after exposure to physical assault: An 8 years longitudinal study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2022; 37(9-10):NP7679-706. [DOI:10.1177/0886260520970314] [PMID]

- Jaffe AE, Walton TO, Walker DD, Kaysen DL. Social support and treatment utilization for posttraumatic stress disorder: Examining reciprocal relations among active duty service members. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2023; 36(3):537-48. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22908] [PMID]

- Grocott LR, Schlechter TE, Wilder SMJ, O'Hair CM, Gidycz CA, Shorey RC. Social support as a buffer of the association between sexual assault and trauma symptoms among transgender and gender diverse individuals. Journal of interpersonal Violence. 2023; 38(1-2):NP1738-61. [DOI:10.1177/08862605221092069] [PMID]

- Fuchkan Buljan N. Burden of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) - health, social, and economic impacts of exposure to the London bombings [PhD dissertation]. London: School of Economics and Political Science; 2015. [Link]

- Eom KS, Kim JH, Yoon SH, Lee SJ, Park KJ, Ha SK, et al. Gender differences in adult traumatic brain injury according to the Glasgow coma scale: A multicenter descriptive study. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2021; 24(6):333-43.[DOI:10.1016/j.cjtee.2021.06.004] [PMID]

- Rugema L, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. Traumatic episodes and mental health effects in young men and women in Rwanda, 17 years after the genocide. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(6):e006778. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006778] [PMID]

- Parcesepe AM, Filiatreau LM, Ebasone PV, Dzudie A, Pence BW, Wainberg M, et al. Prevalence of potentially traumatic events and symptoms of depression, anxiety, hazardous alcohol use, and post-traumatic stress disorder among people with HIV initiating HIV care in Cameroon. BMC Psychiatry. 2023; 23(1):150. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-023-04630-1] [PMID]

- Madoro D, Kerebih H, Habtamu Y, G/Tsadik M, Mokona H, Molla A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and associated factors among internally displaced people in South Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2020; 16:2317-26. [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S267307] [PMID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2023/06/16 | Accepted: 2023/10/28 | Published: 2024/07/1

Received: 2023/06/16 | Accepted: 2023/10/28 | Published: 2024/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |