Volume 14, Issue 3 (May & Jun 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(3): 269-276 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Javdan M, AhmadiTeifakani B, Samavi A. Adolescent Self-harm Behavior Based on Depression, Family Emotional Climate, School Identity, and Academic Performance. J Research Health 2024; 14 (3) :269-276

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2371-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2371-en.html

1- Department of Counseling and Psychology, School of Humanities, University of Hormozgan, Bandar Abbas, Iran. , javdan@hormozgan.ac.ir

2- Department of General Psychology, School of Humanities, University of Hormozgan, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

3- Department of Educational Sciences, School of Humanities, University of Hormozgan, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

2- Department of General Psychology, School of Humanities, University of Hormozgan, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

3- Department of Educational Sciences, School of Humanities, University of Hormozgan, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 636 kb]

(1304 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3889 Views)

Full-Text: (935 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a dynamic and exhilarating stage in the family life cycle, and puberty brings about significant changes in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions [1]. As a result, adolescents become highly sensitive and vulnerable to the rapid and all-encompassing changes that occur in various aspects of their personality, which can significantly impact their development [2]. Adolescents often face different selves with new needs and demands, which require novel and various mechanisms for self-management. Therefore, they need empathy and understanding from those around them more than ever to help organize and regulate their vulnerable mind. Additionally, due to their limited self-knowledge and the demands of adolescence, they often require the guidance and support of caring and knowledgeable adults [2].

The adolescent brain operates differently than the adult brain. The transition from puberty to adulthood involves both gonadal and behavioral maturation. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have revealed that melanogenesis, the process of creating the insulating layer around nerve fibers for efficient communication, continues from childhood, and the brain’s region-specific neurocircuitry remains structurally and functionally vulnerable to impulsive behaviors related to sex, food, and sleep [3].

Self-harm is defined as the deliberate act of self-injury without suicidal intent [4]. Non-suicidal self-injury involves repeatedly inflicting superficial but painful injuries on the surface of the body, often to reduce negative emotions such as tension, anxiety, and self-blame or to solve interpersonal problems [5]. Sometimes, people may perceive the self-injury as a punishment they deserve. The act of self-harm often provides an immediate sense of relief, but if it occurs frequently, it can become more urgent and compulsive, similar to addiction [6]. Adolescent suicide is a global issue, and it is crucial to identify risk factors for suicidal ideation or attempts [7]. However, few studies have examined potential gender differences in the association between the timing of puberty and self-injury.

Previous research has reported a consistent association between early puberty and an increased risk of self-harm in females [6]. Self-harm, which can refer to self-poisoning or self-injury without regard for intent, is a major public health concern for teenagers. Approximately one in six adolescents engage in self-harm, and half of them report repeated incidents of self-harm [8].

Examining variables that can help predict self-harming behaviors is crucial. One important factor that plays a determining role in self-harm among teenagers is the emotional climate of the family [9]. Studies have shown that the quality of family members’ communication and emotional bonds can affect the vulnerability of teenagers to self-harm [10]. Depression is another variable that can influence self-harming behavior in teenagers. Mood and anxiety disorders in adolescents and adults are associated with various negative consequences, such as future mood disorders and anxiety, drug use, lower levels of education, unemployment, and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors [11]. Therefore, self-harm and suicide are also considered as harms caused by depression, and identifying and treating depression can be effective in reducing self-harm.

School identity is another variable that is linked to self-harm behavior in teenagers [12]. Learning and acquiring basic skills are essential for children and teenagers, and in most societies, going to school from a young age is an important duty that families and societies entrust to individuals. Children and teenagers often have no choice but to attend school to gain the approval of others. Since adolescents spend many hours in school, having a sense of belonging and attachment to the school can make those moments enjoyable and desirable. In contrast, a lack of connection to the school can make those moments unbearable and disappointing [12]. In the school context, a sense of belonging is considered a basic psychological need. When teenagers feel a sense of belonging, they perceive themselves as a critical, significant, and valuable part of the school community [13]. Research has shown a correlation between students’ sense of belonging and engagement in self-harm behaviors, suicidal thoughts, and attempted suicide [14]. Female students across all educational levels report a higher incidence of self-harm behaviors than boys [15]. Students who report the lowest sense of belonging to the school often cite irrational expectations from the school and family as a reason for their lack of connection to the school [16].

In addition to the variables mentioned, students who are rejected in their school environment are more likely to suffer from emotional health problems than those who are accepted. The educational progress of adolescents and the parent’s interest in their academic performance can also contribute to the occurrence of harmful behaviors. The effects of childhood adversity on self-harm among juveniles and psychopathology and school performance at the population level are mediated by aggression, impulsivity, school performance, and substance abuse [17]. The prevalence of suicide and the risk of suicidal thoughts in students are at their highest when they have simultaneous concerns about interpersonal relationships at school and home, and academic performance. When looking at students who expressed concerns about all three factors simultaneously, rates of suicidal ideation were higher among those with lower levels of support and less trusting relationships with family members. Therefore, adolescent suicide prevention strategies should include reducing concerns about interpersonal relationships in the family, interpersonal relationships at school, and academic performance [18]. Psychosocial, family, and genetic health disorders, along with poverty, stressful life events, and academic failure, are essential factors related to depression and self-harm of these teenagers. These were considered to be effective factors in the rise of self-harm among the teenagers of this village. Investigating and identifying these factors and informing families and teenagers are preliminary steps to reduce the various aspects of self-harm and generally ensure the health of teenagers in this village. Addressing this issue is crucial, given adolescents’ recent increase in self-harming behaviors.

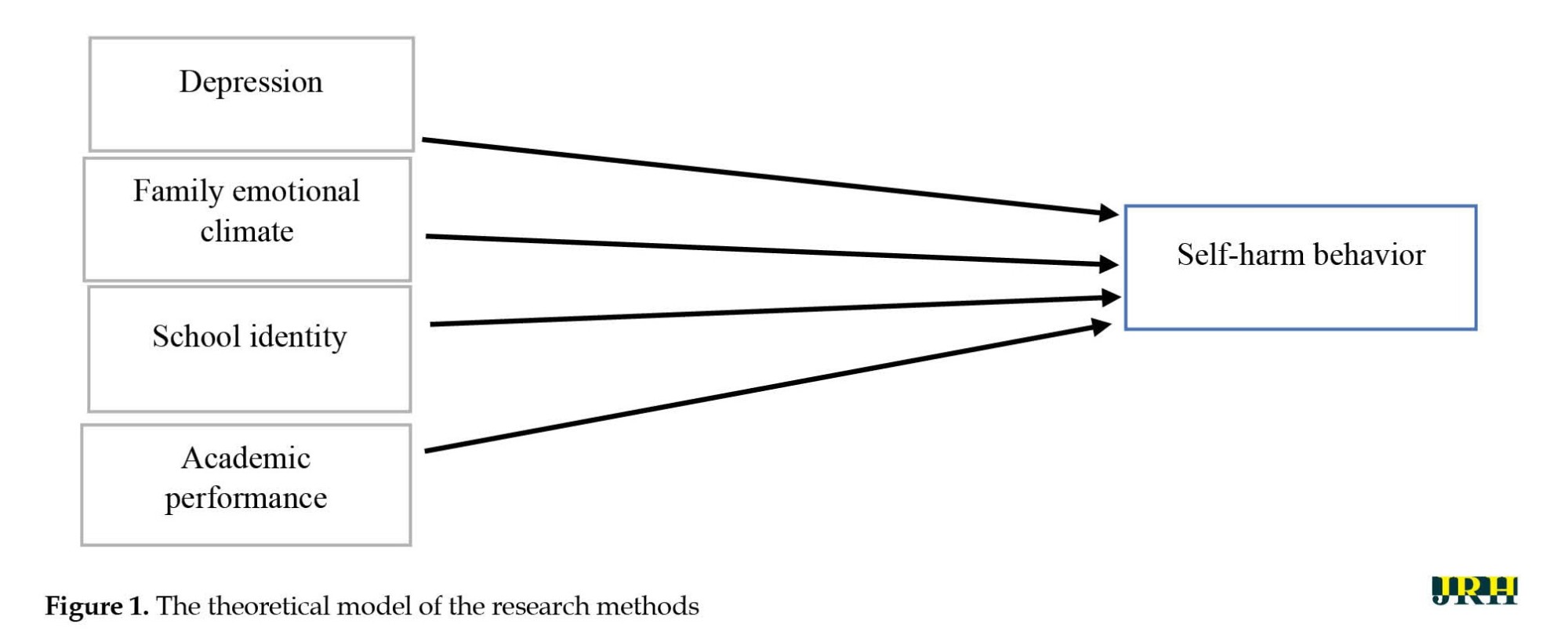

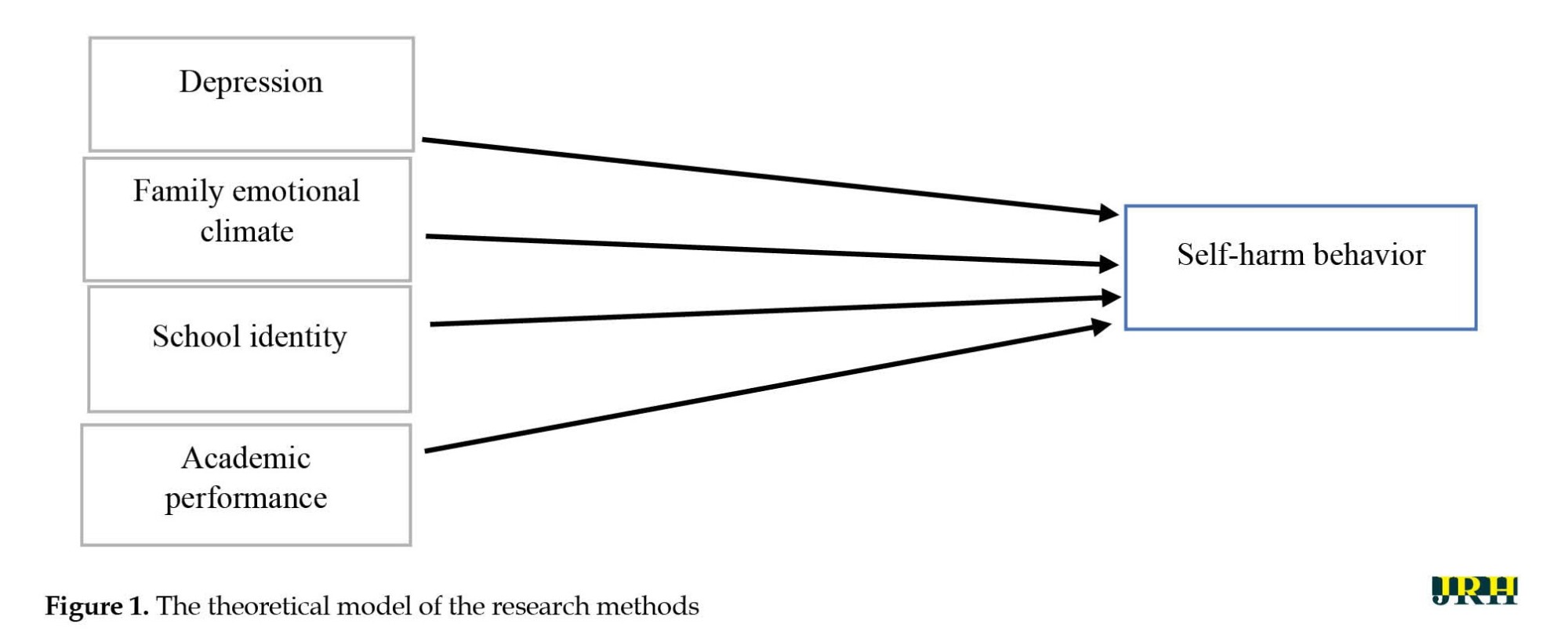

Researchers could not find research that examines the effect of depression, family emotional climate, school identity, and academic performance on self-harm behavior. According to the residents of this village, 34 teenagers aged between 12 and 24 were on the verge of committing suicide. Before this research, six people had committed suicide because of interpersonal issues or family problems. The researchers first investigated field issues in schools and localities and found the self-harm behavior factors of female teenagers. Therefore, the research mentioned above was conducted to identify the effective factors on the self-harm behavior of female teenagers in this village and its prevention. The main goal of this study is to address and predict the factors that affect self-harm behavior in adolescents. We hypothesized a relationship between depression, family emotional climate, school identity, academic performance, and self-harm behavior in adolescents.

Methods

According to the data collection method, this research is based on fundamental objectives and uses regular and closed response standard scales. In this research, descriptive statistics were first used to determine the mean and median. Then, the Pearson correlation coefficient and multivariate linear regression were used in the inferential statistics section. All data analysis was done using SPSS software, version 26. To comply with ethical considerations, the necessary arrangements were made with the village headman, village councils, and school parents. The research on the factors influencing self-harm was conducted among female adolescents in Banoband Tazian Village of Bandar Abbas City, Iran, in 2022.

Research samples

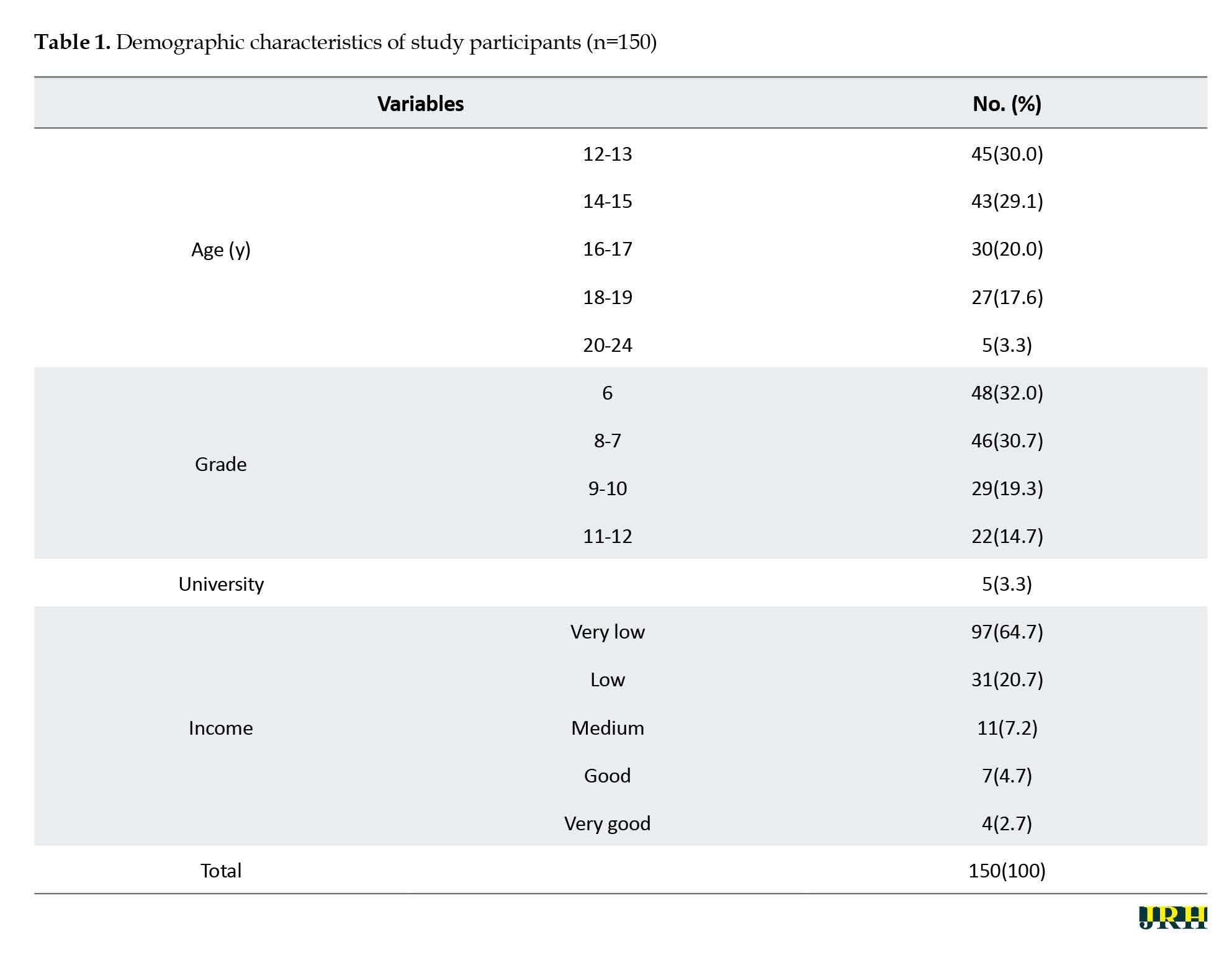

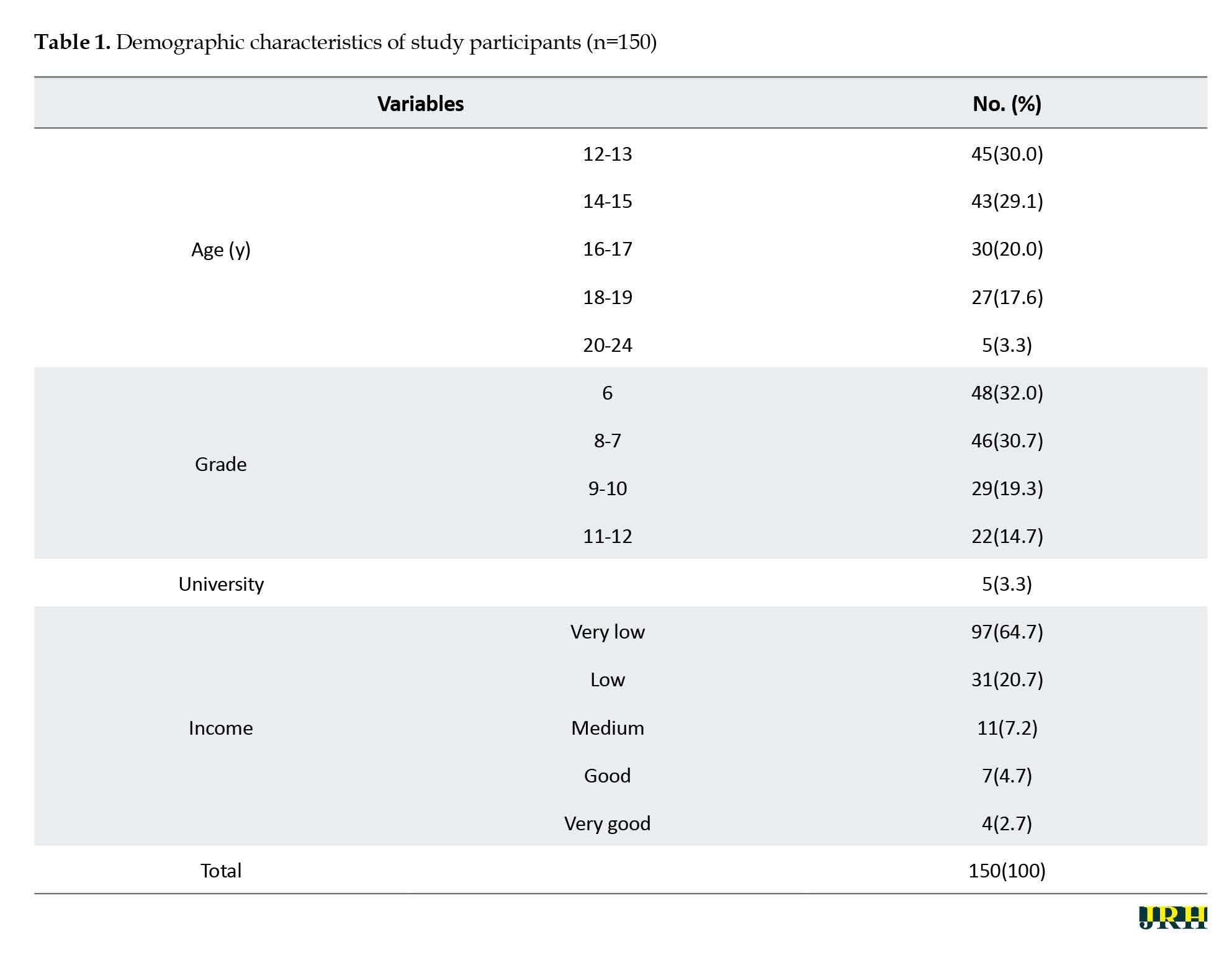

Green argues for the utilization of techniques that take into consideration the effect size when determining the appropriate sample size. Subsequently, we collected data from a statistical population comprising 150 individuals for our study [19]. The statistical population of this study consisted of all female adolescents aged 12 to 24 years residing in that village in June 2022. There were 150 girls who lived in the village with their families. The census method was used to increase the credibility of the research, and all 150 girls who met the inclusion criteria and desired to participate were recruited. After explaining the research objectives and assuring samples of the confidentiality of their information, they were given questionnaires to complete. Demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1.

Measurement instruments

The following five questionnaires were used to collect data in the present study.

The Kutcher adolescent depression scale

The Kutcher adolescent depression scale is an 11-item scale that was developed by Brooks [20] to measure symptoms and severity of depression in adolescents aged 12 to 20 years. Participants respond to four-choice items (0 to 3), and scores range from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. The scale has two subscales (basic depression and suicidality factor) and has a reported Cronbach α coefficient of 0.90 and a reliability coefficient of 0.87 using the two-half method [20]. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the whole scale was 0.82.

The deliberate self-harm inventory

The deliberate self-harm inventory questionnaire was developed by Gratz [21] to measure types of self-harm behaviors in non-patient populations. It includes 17 descriptive statements about intentional self-harm behaviors, and participants score each item as “yes” (1) or “no” (0). The total score ranges from 0 to 17, with higher scores indicating a higher level of self-harm. Gratz calculated the Cronbach α coefficient of the questionnaire as 0.82 and its test re-test reliability coefficient after two weeks as 0.68 [21]. Payvastehgar reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.71 in the Iranian sample, indicating acceptable reliability. The test’s content validity was also verified through expert opinions in psychology and educational sciences [22]. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient of this inventory was found to be 0.84.

Affective family climate

The affective family climate (AFC) questionnaire was developed by Alfred B. Hillburn to measure the level of affection in parent-child interactions [23]. The scale includes 16 questions grouped into eight subscales: Affection, caressing, confirming, shared experiences, giving gifts, encouraging, trusting, and feeling safe. Participants respond to a range of five answers for each question. The reported Cronbach α coefficient was 0.82 [24]. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the AFC was found to be 0.81.

The dual school climate and school identification measure-student

The dual school climate and school identification measure-student scale was developed by Lee et al. [15] to measure school climate and identity. It includes 38 six-choice items grouped into five parts: Student-student relations, student-staff relations, academic emphasis, shared values and approach, and school identification. The total score ranges from 38 to 228, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude towards the school’s climate and identity. Imamgholivand et al. reported this questionnaire’s content, form, and criteria validities as suitable [25]. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the SCASIM-St was 0.81.

The academic performance questionnaire

The academic performance questionnaire has 48 items developed by Pham and Taylor to measure academic performance [26]. Developers reported its reliability coefficient as 0.74 using the Cronbach α method with favorable validity. Participants respond to five-point items, and higher scores indicate a higher academic performance. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the academic performance questionnaire was 0.81.

Study procedure

To collect information, Benoband Pasang village of Tazian County, located 30 km from Bandar Abbas City, was visited on June 5, 2022. The study took 35 days and lasted until July 11, 2022. The samples were collected using the census method of all female teenagers aged 12 to 24 years after the necessary coordination with the village headman, village council, and school teachers. The study’s objectives were explained to the people to attract the participants’ opinion.

Results

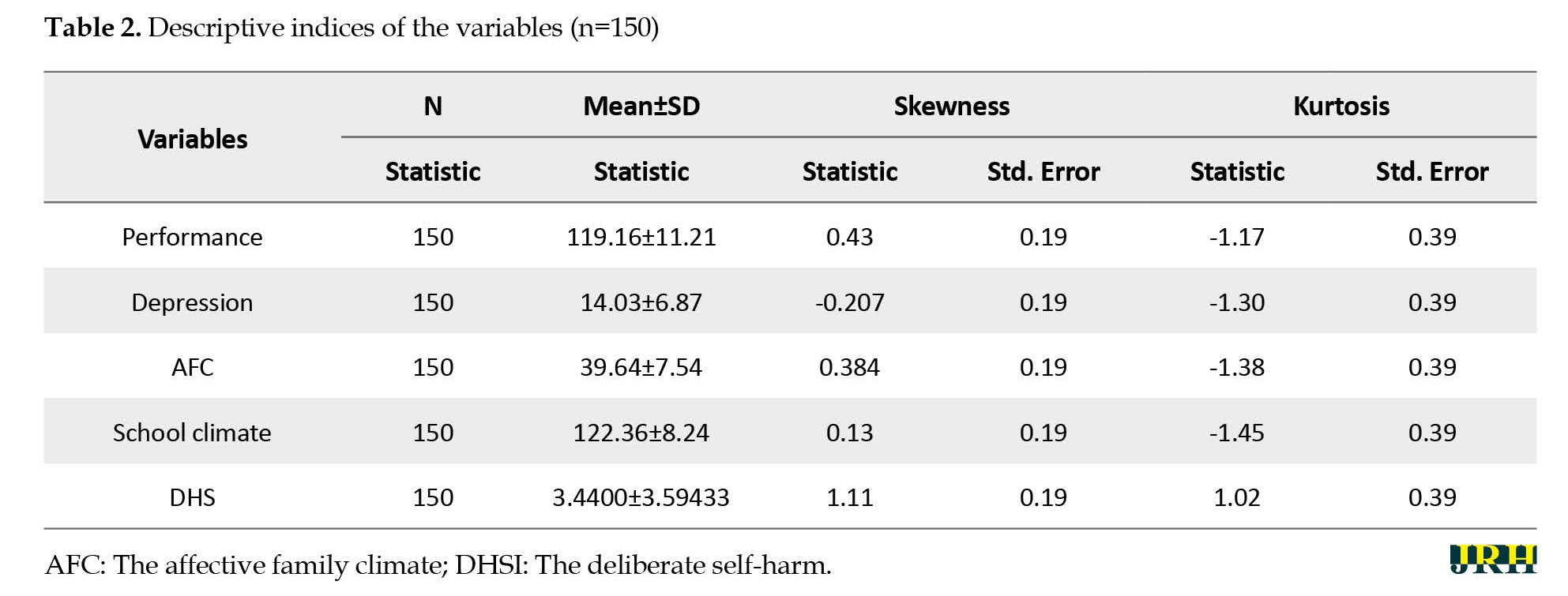

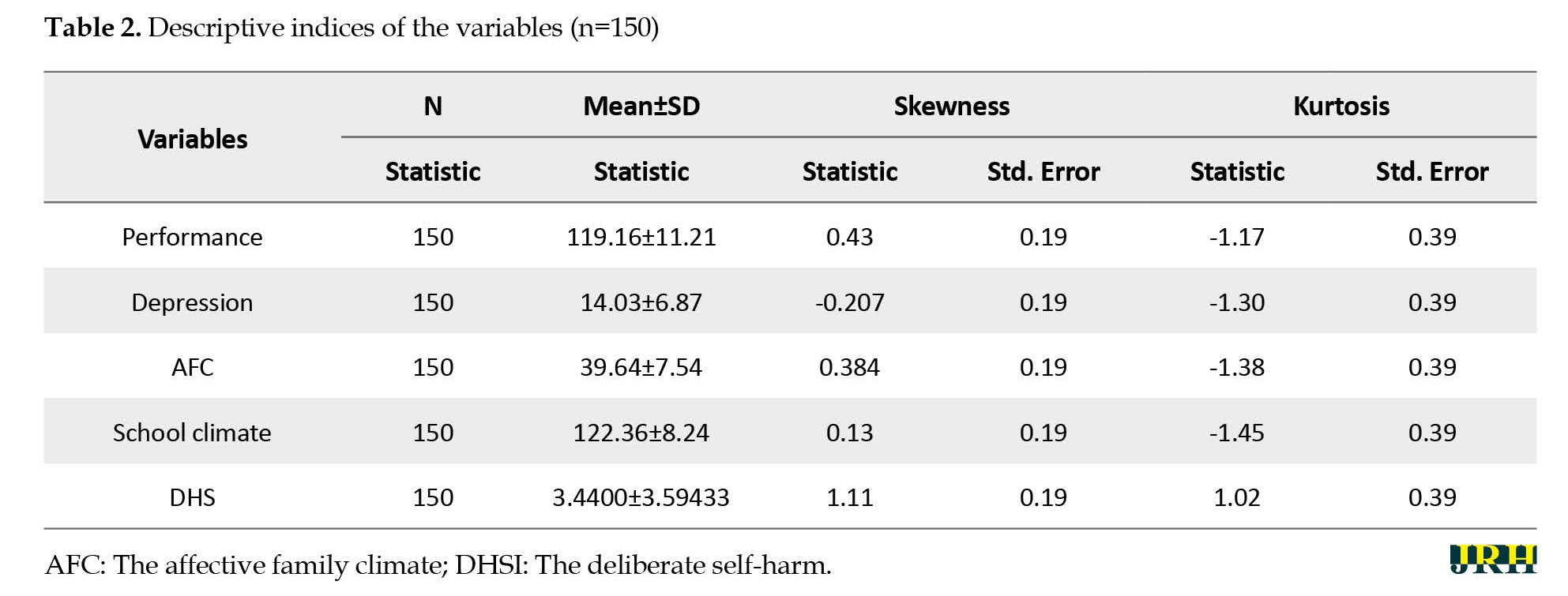

Table 2 presents the descriptive indices of the study variables, including the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis.

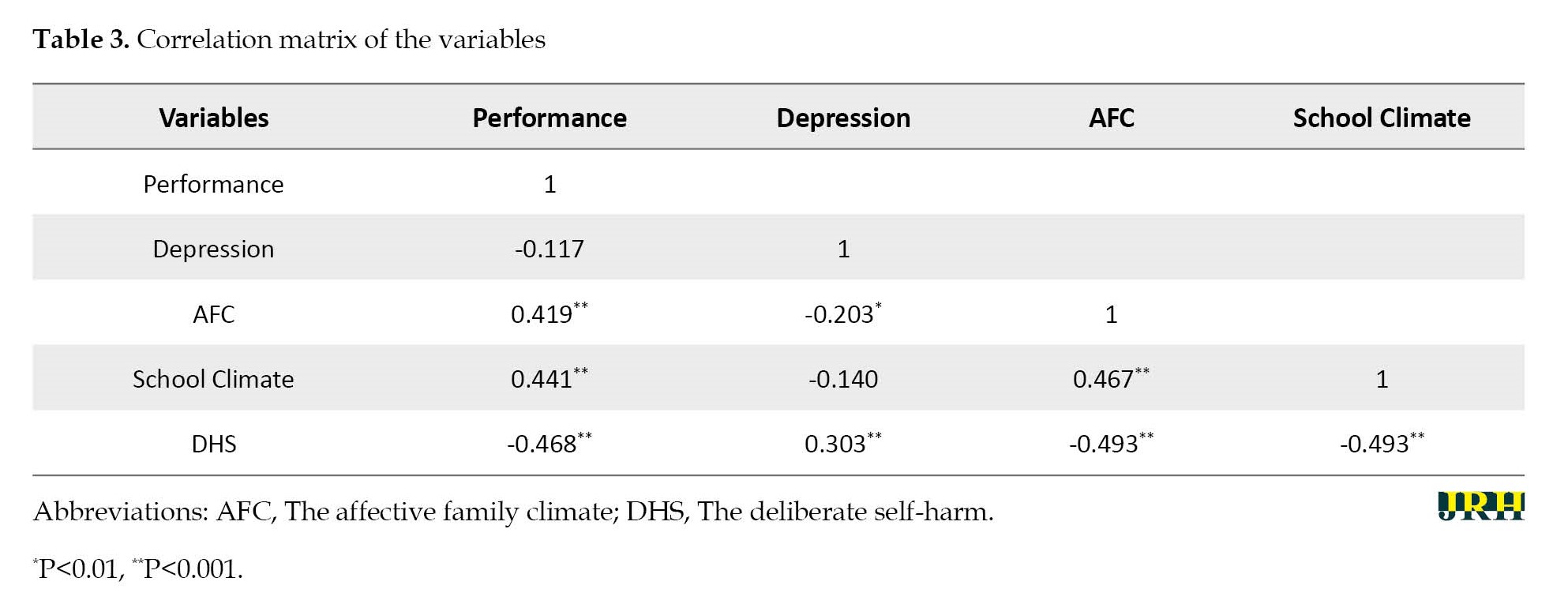

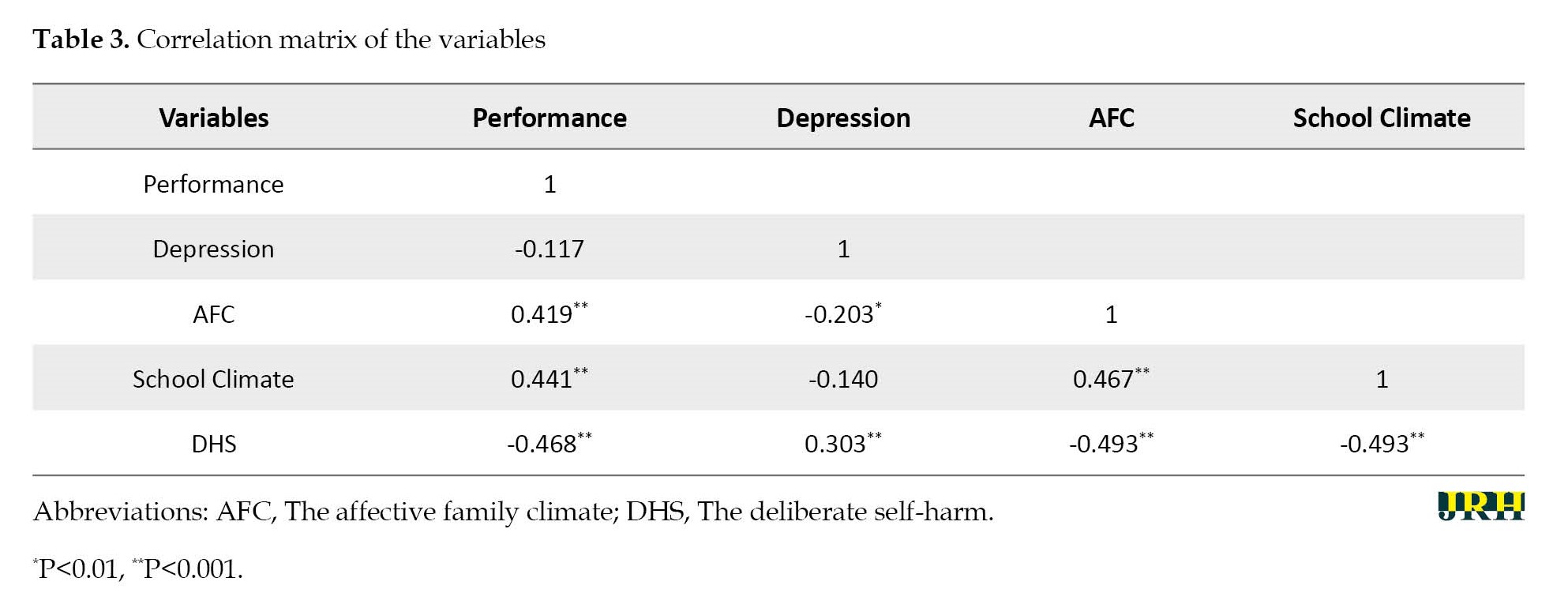

The skewness and kurtosis values indicate that the data for all variables are normally distributed. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the variables.

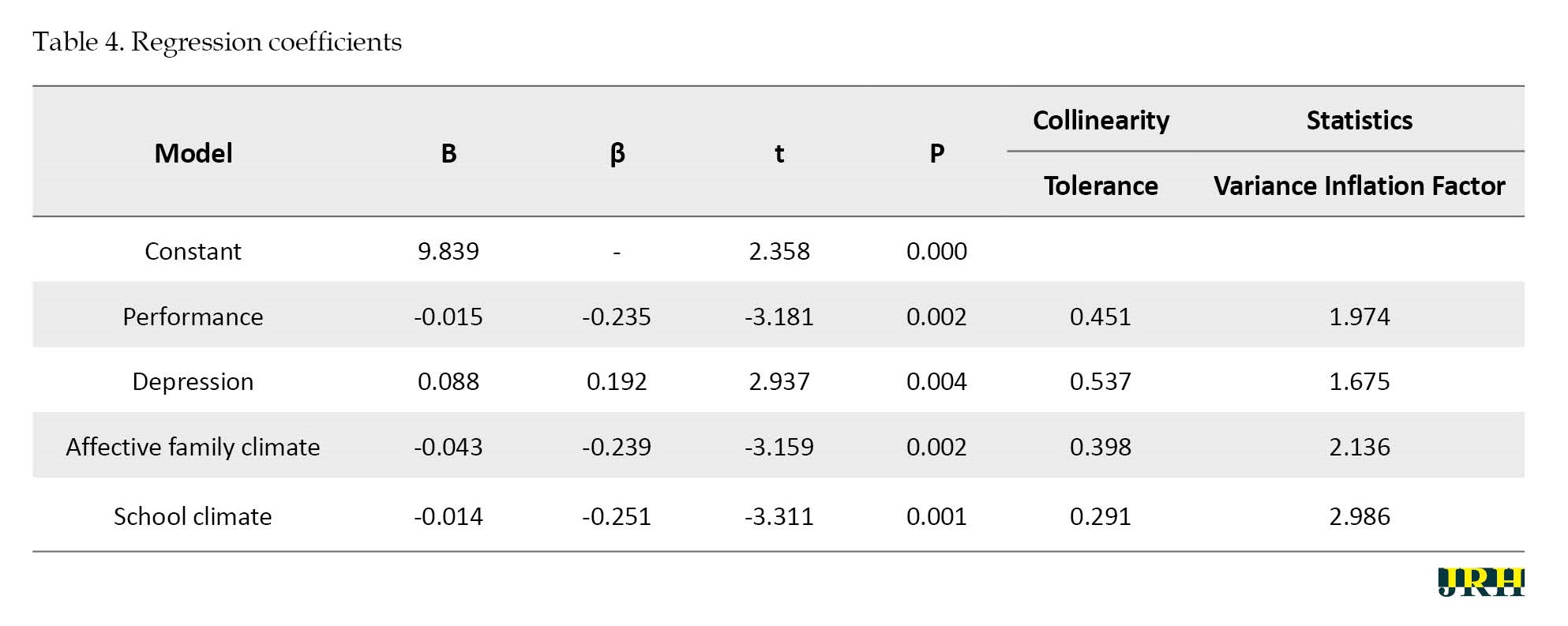

The results of the assumptions of the multiple regression test are as follows.

A. Errors are independent of each other. The Durbin-Watson test was used to check this hypothesis. According to reliable sources, if the statistic value of this test is between 1 and 2.5, the independence of observations can be accepted. Based on the analysis, the value of this statistic in the present study is equal to 1.61, which confirms the independence of the observations.

B. The errors have a normal distribution with a zero mean. This is also true in the present study, and the errors have a normal distribution. The mean errors are close to zero, and the standard deviation is close to one.

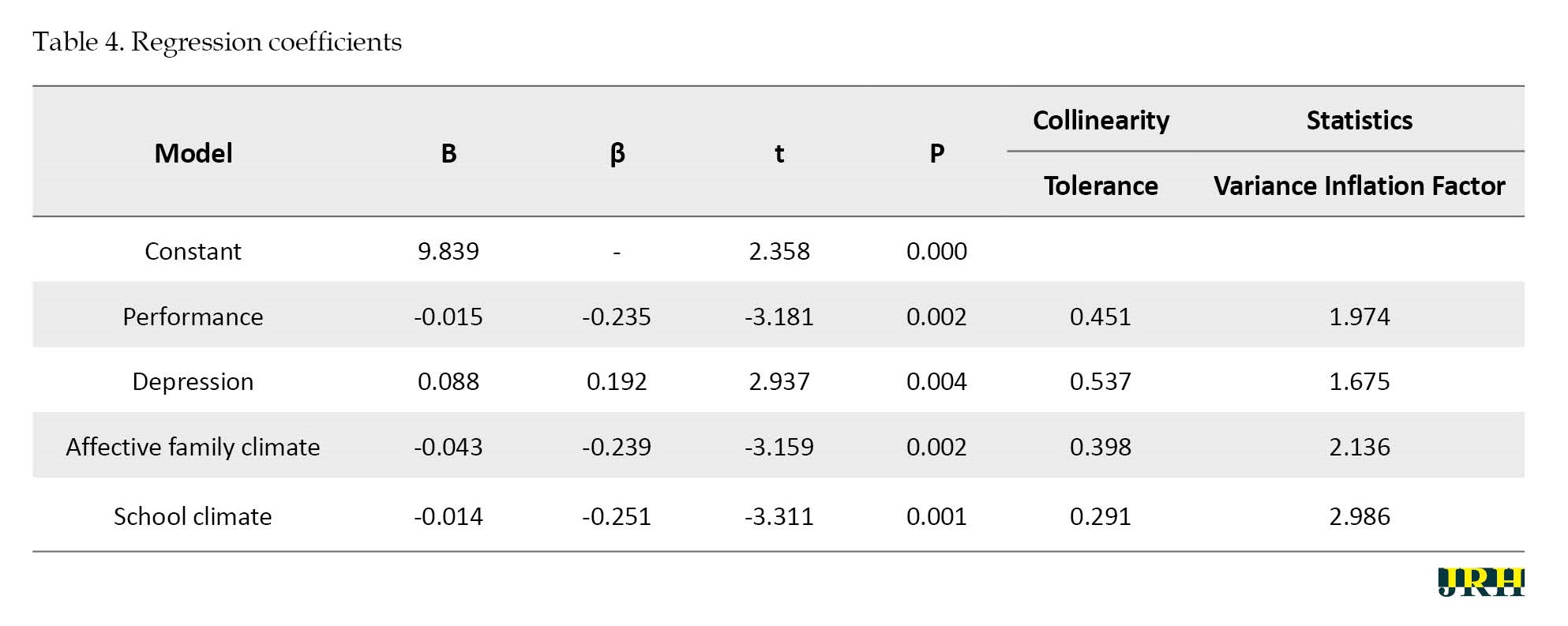

C. There is non-collinearity between independent variables. The tolerance statistics and variance inflation factors were used to investigate this. As seen in Table 4, the tolerance value is close to 1, and the variance inflation factor is less than 3, which is relatively favorable.

There is no collinearity between the independent variables. As a result, by observing the assumptions of the regression analysis test, this test can be used to check the hypotheses of the current research.

According to the analysis, the adjusted coefficient of determination is 0.39 (R=0.64, R2=0.41), indicating that the predictor variables account for 39% of the variance (changes) in the criterion variable (self-harm). Moreover, the F (25.16) is significant (P<0.01), suggesting that the predictor variables included in the model significantly predict self-harm behaviors.

Table 4 indicates that affective family climate, school climate, and academic performance have a negative and significant impact on self-harm behaviors. In contrast, depression has a positive and significant effect on self-harm behaviors.

Discussion

The present study aimed to predict self-harm behavior in adolescents based on variables such as depression, affective family climate, school identity, and academic performance. The results showed a negative correlation coefficient between affective family climate and self-harm behavior, indicating that as affective family climate increases, self-harm behavior decreases. These findings are consistent with previous research [9]. They found that family climate influences the frequency of deliberate self-harm through emotion regulation skills. Other studies have found that family dysfunction, absence of one or both parents, history of risky behavior in the family, and parental neglect are factors that contribute to risky behavior in teenagers [27]. Some researchers identified protective factors as understanding family, having friends, and higher school competence [28].

The findings of the present study also revealed a positive association between depression in teenagers and their engagement in self-harm behaviors. These results indicate that as depression increases in teenagers, so does their likelihood of engaging in harmful behaviors. This finding is consistent with some studies [6, 29, 30, 31]. These studies have shown that self-harm behaviors are often used as a coping mechanism in response to negative and stressful situations, particularly feelings of anger and depression. Furthermore, depression and self-harm behaviors have been identified as predictors of suicide.

One possible explanation for this finding is that self-harm serves as a means for individuals with depression to alleviate feelings of confusion and helplessness. Depression is a common psychological disorder that significantly impacts an individual’s attitude toward themselves, others, and the world around them. If left untreated, individuals with chronic depression may engage in direct or indirect self-harm behaviors as a way to temporarily relieve these negative emotions.

Field observations by the researchers also revealed that boys and girls lack the communication skills necessary for building positive relationships. This lack of training in the family, school, and other educational environments can result in adolescents facing challenges that require emotional management, problem-solving, and decision-making skills. Additionally, providing parenting education to familiarize parents with adolescents’ unique emotional and social characteristics can lead to a greater understanding of their adolescent children and promote their mental and psychological well-being within the family.

Attachment theories highlight the importance of parent-child relationships in shaping personality and behavior and emphasize the need for emotional support and attention from caregivers from birth. A lack of a suitable emotional climate in the family can cause a teenager to withdraw from family relationships during adolescence. Conversely, teenagers who perceive themselves as having a place and value within the family and experience a sense of security and peace are less likely to engage in self-harm behavior. Thus, the emotional climate of the family has a significant impact on harmful behavior in teenagers. The findings of the present study are in line with those of previous research, highlighting the importance of a supportive and positive family environment in preventing self-harm behavior in adolescents [10, 17].

Conclusion

Identifying and treating depression can be effective in reducing self-harm behaviors. Adjusting educational demands and setting realistic expectations for students can also foster their interest in school. A favorable emotional climate in the family can contribute to a student’s mental peace, concentration, and vitality, which can also reduce the likelihood of self-harm. To prevent self-harm behaviors in adolescents, it is crucial to improve interpersonal relationships within the family, interpersonal relationships at school, and academic performance.

This research, like other research in the humanities, has also been associated with limitations, such as the use of questionnaires, self-assessment, cross-sectional research, the implementation of research on a group, a specific place and time, the lack of control over the cause-and-effect relationships of variables and the method of conducting the research. Therefore, the internal and external validity of the current research should be handled with caution. However, the researchers focused on predicting and identifying these factors as much as possible and using the necessary plan to reduce them.

It is suggested that other researchers investigate the issue more deeply and more accurately in future research through a case study in one or more families and to identify factors affecting self-harming behaviors in other groups at risk, including boys. Also, it is suggested that effective research be conducted in the family and school environment to reduce family tensions and improve the psychosocial climate of the school.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.HUMS.REC.1401.261). The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, funding administration and writing Moosa Javdan; Methodology, Review and editing: Abdolvahab Samavi Abdolvahab Samavi; Investigation: Beheshteh AhmadiTeifakani; Data collection: All authors; Data analysis: Moosa Javdan and Abdolvahab Samavi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the residents of Benoband Village, participating students, parents, and school teachers.

References

Adolescence is a dynamic and exhilarating stage in the family life cycle, and puberty brings about significant changes in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions [1]. As a result, adolescents become highly sensitive and vulnerable to the rapid and all-encompassing changes that occur in various aspects of their personality, which can significantly impact their development [2]. Adolescents often face different selves with new needs and demands, which require novel and various mechanisms for self-management. Therefore, they need empathy and understanding from those around them more than ever to help organize and regulate their vulnerable mind. Additionally, due to their limited self-knowledge and the demands of adolescence, they often require the guidance and support of caring and knowledgeable adults [2].

The adolescent brain operates differently than the adult brain. The transition from puberty to adulthood involves both gonadal and behavioral maturation. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have revealed that melanogenesis, the process of creating the insulating layer around nerve fibers for efficient communication, continues from childhood, and the brain’s region-specific neurocircuitry remains structurally and functionally vulnerable to impulsive behaviors related to sex, food, and sleep [3].

Self-harm is defined as the deliberate act of self-injury without suicidal intent [4]. Non-suicidal self-injury involves repeatedly inflicting superficial but painful injuries on the surface of the body, often to reduce negative emotions such as tension, anxiety, and self-blame or to solve interpersonal problems [5]. Sometimes, people may perceive the self-injury as a punishment they deserve. The act of self-harm often provides an immediate sense of relief, but if it occurs frequently, it can become more urgent and compulsive, similar to addiction [6]. Adolescent suicide is a global issue, and it is crucial to identify risk factors for suicidal ideation or attempts [7]. However, few studies have examined potential gender differences in the association between the timing of puberty and self-injury.

Previous research has reported a consistent association between early puberty and an increased risk of self-harm in females [6]. Self-harm, which can refer to self-poisoning or self-injury without regard for intent, is a major public health concern for teenagers. Approximately one in six adolescents engage in self-harm, and half of them report repeated incidents of self-harm [8].

Examining variables that can help predict self-harming behaviors is crucial. One important factor that plays a determining role in self-harm among teenagers is the emotional climate of the family [9]. Studies have shown that the quality of family members’ communication and emotional bonds can affect the vulnerability of teenagers to self-harm [10]. Depression is another variable that can influence self-harming behavior in teenagers. Mood and anxiety disorders in adolescents and adults are associated with various negative consequences, such as future mood disorders and anxiety, drug use, lower levels of education, unemployment, and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors [11]. Therefore, self-harm and suicide are also considered as harms caused by depression, and identifying and treating depression can be effective in reducing self-harm.

School identity is another variable that is linked to self-harm behavior in teenagers [12]. Learning and acquiring basic skills are essential for children and teenagers, and in most societies, going to school from a young age is an important duty that families and societies entrust to individuals. Children and teenagers often have no choice but to attend school to gain the approval of others. Since adolescents spend many hours in school, having a sense of belonging and attachment to the school can make those moments enjoyable and desirable. In contrast, a lack of connection to the school can make those moments unbearable and disappointing [12]. In the school context, a sense of belonging is considered a basic psychological need. When teenagers feel a sense of belonging, they perceive themselves as a critical, significant, and valuable part of the school community [13]. Research has shown a correlation between students’ sense of belonging and engagement in self-harm behaviors, suicidal thoughts, and attempted suicide [14]. Female students across all educational levels report a higher incidence of self-harm behaviors than boys [15]. Students who report the lowest sense of belonging to the school often cite irrational expectations from the school and family as a reason for their lack of connection to the school [16].

In addition to the variables mentioned, students who are rejected in their school environment are more likely to suffer from emotional health problems than those who are accepted. The educational progress of adolescents and the parent’s interest in their academic performance can also contribute to the occurrence of harmful behaviors. The effects of childhood adversity on self-harm among juveniles and psychopathology and school performance at the population level are mediated by aggression, impulsivity, school performance, and substance abuse [17]. The prevalence of suicide and the risk of suicidal thoughts in students are at their highest when they have simultaneous concerns about interpersonal relationships at school and home, and academic performance. When looking at students who expressed concerns about all three factors simultaneously, rates of suicidal ideation were higher among those with lower levels of support and less trusting relationships with family members. Therefore, adolescent suicide prevention strategies should include reducing concerns about interpersonal relationships in the family, interpersonal relationships at school, and academic performance [18]. Psychosocial, family, and genetic health disorders, along with poverty, stressful life events, and academic failure, are essential factors related to depression and self-harm of these teenagers. These were considered to be effective factors in the rise of self-harm among the teenagers of this village. Investigating and identifying these factors and informing families and teenagers are preliminary steps to reduce the various aspects of self-harm and generally ensure the health of teenagers in this village. Addressing this issue is crucial, given adolescents’ recent increase in self-harming behaviors.

Researchers could not find research that examines the effect of depression, family emotional climate, school identity, and academic performance on self-harm behavior. According to the residents of this village, 34 teenagers aged between 12 and 24 were on the verge of committing suicide. Before this research, six people had committed suicide because of interpersonal issues or family problems. The researchers first investigated field issues in schools and localities and found the self-harm behavior factors of female teenagers. Therefore, the research mentioned above was conducted to identify the effective factors on the self-harm behavior of female teenagers in this village and its prevention. The main goal of this study is to address and predict the factors that affect self-harm behavior in adolescents. We hypothesized a relationship between depression, family emotional climate, school identity, academic performance, and self-harm behavior in adolescents.

Methods

According to the data collection method, this research is based on fundamental objectives and uses regular and closed response standard scales. In this research, descriptive statistics were first used to determine the mean and median. Then, the Pearson correlation coefficient and multivariate linear regression were used in the inferential statistics section. All data analysis was done using SPSS software, version 26. To comply with ethical considerations, the necessary arrangements were made with the village headman, village councils, and school parents. The research on the factors influencing self-harm was conducted among female adolescents in Banoband Tazian Village of Bandar Abbas City, Iran, in 2022.

Research samples

Green argues for the utilization of techniques that take into consideration the effect size when determining the appropriate sample size. Subsequently, we collected data from a statistical population comprising 150 individuals for our study [19]. The statistical population of this study consisted of all female adolescents aged 12 to 24 years residing in that village in June 2022. There were 150 girls who lived in the village with their families. The census method was used to increase the credibility of the research, and all 150 girls who met the inclusion criteria and desired to participate were recruited. After explaining the research objectives and assuring samples of the confidentiality of their information, they were given questionnaires to complete. Demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1.

Measurement instruments

The following five questionnaires were used to collect data in the present study.

The Kutcher adolescent depression scale

The Kutcher adolescent depression scale is an 11-item scale that was developed by Brooks [20] to measure symptoms and severity of depression in adolescents aged 12 to 20 years. Participants respond to four-choice items (0 to 3), and scores range from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. The scale has two subscales (basic depression and suicidality factor) and has a reported Cronbach α coefficient of 0.90 and a reliability coefficient of 0.87 using the two-half method [20]. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the whole scale was 0.82.

The deliberate self-harm inventory

The deliberate self-harm inventory questionnaire was developed by Gratz [21] to measure types of self-harm behaviors in non-patient populations. It includes 17 descriptive statements about intentional self-harm behaviors, and participants score each item as “yes” (1) or “no” (0). The total score ranges from 0 to 17, with higher scores indicating a higher level of self-harm. Gratz calculated the Cronbach α coefficient of the questionnaire as 0.82 and its test re-test reliability coefficient after two weeks as 0.68 [21]. Payvastehgar reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.71 in the Iranian sample, indicating acceptable reliability. The test’s content validity was also verified through expert opinions in psychology and educational sciences [22]. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient of this inventory was found to be 0.84.

Affective family climate

The affective family climate (AFC) questionnaire was developed by Alfred B. Hillburn to measure the level of affection in parent-child interactions [23]. The scale includes 16 questions grouped into eight subscales: Affection, caressing, confirming, shared experiences, giving gifts, encouraging, trusting, and feeling safe. Participants respond to a range of five answers for each question. The reported Cronbach α coefficient was 0.82 [24]. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the AFC was found to be 0.81.

The dual school climate and school identification measure-student

The dual school climate and school identification measure-student scale was developed by Lee et al. [15] to measure school climate and identity. It includes 38 six-choice items grouped into five parts: Student-student relations, student-staff relations, academic emphasis, shared values and approach, and school identification. The total score ranges from 38 to 228, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude towards the school’s climate and identity. Imamgholivand et al. reported this questionnaire’s content, form, and criteria validities as suitable [25]. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the SCASIM-St was 0.81.

The academic performance questionnaire

The academic performance questionnaire has 48 items developed by Pham and Taylor to measure academic performance [26]. Developers reported its reliability coefficient as 0.74 using the Cronbach α method with favorable validity. Participants respond to five-point items, and higher scores indicate a higher academic performance. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the academic performance questionnaire was 0.81.

Study procedure

To collect information, Benoband Pasang village of Tazian County, located 30 km from Bandar Abbas City, was visited on June 5, 2022. The study took 35 days and lasted until July 11, 2022. The samples were collected using the census method of all female teenagers aged 12 to 24 years after the necessary coordination with the village headman, village council, and school teachers. The study’s objectives were explained to the people to attract the participants’ opinion.

Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive indices of the study variables, including the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis.

The skewness and kurtosis values indicate that the data for all variables are normally distributed. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the variables.

The results of the assumptions of the multiple regression test are as follows.

A. Errors are independent of each other. The Durbin-Watson test was used to check this hypothesis. According to reliable sources, if the statistic value of this test is between 1 and 2.5, the independence of observations can be accepted. Based on the analysis, the value of this statistic in the present study is equal to 1.61, which confirms the independence of the observations.

B. The errors have a normal distribution with a zero mean. This is also true in the present study, and the errors have a normal distribution. The mean errors are close to zero, and the standard deviation is close to one.

C. There is non-collinearity between independent variables. The tolerance statistics and variance inflation factors were used to investigate this. As seen in Table 4, the tolerance value is close to 1, and the variance inflation factor is less than 3, which is relatively favorable.

There is no collinearity between the independent variables. As a result, by observing the assumptions of the regression analysis test, this test can be used to check the hypotheses of the current research.

According to the analysis, the adjusted coefficient of determination is 0.39 (R=0.64, R2=0.41), indicating that the predictor variables account for 39% of the variance (changes) in the criterion variable (self-harm). Moreover, the F (25.16) is significant (P<0.01), suggesting that the predictor variables included in the model significantly predict self-harm behaviors.

Table 4 indicates that affective family climate, school climate, and academic performance have a negative and significant impact on self-harm behaviors. In contrast, depression has a positive and significant effect on self-harm behaviors.

Discussion

The present study aimed to predict self-harm behavior in adolescents based on variables such as depression, affective family climate, school identity, and academic performance. The results showed a negative correlation coefficient between affective family climate and self-harm behavior, indicating that as affective family climate increases, self-harm behavior decreases. These findings are consistent with previous research [9]. They found that family climate influences the frequency of deliberate self-harm through emotion regulation skills. Other studies have found that family dysfunction, absence of one or both parents, history of risky behavior in the family, and parental neglect are factors that contribute to risky behavior in teenagers [27]. Some researchers identified protective factors as understanding family, having friends, and higher school competence [28].

The findings of the present study also revealed a positive association between depression in teenagers and their engagement in self-harm behaviors. These results indicate that as depression increases in teenagers, so does their likelihood of engaging in harmful behaviors. This finding is consistent with some studies [6, 29, 30, 31]. These studies have shown that self-harm behaviors are often used as a coping mechanism in response to negative and stressful situations, particularly feelings of anger and depression. Furthermore, depression and self-harm behaviors have been identified as predictors of suicide.

One possible explanation for this finding is that self-harm serves as a means for individuals with depression to alleviate feelings of confusion and helplessness. Depression is a common psychological disorder that significantly impacts an individual’s attitude toward themselves, others, and the world around them. If left untreated, individuals with chronic depression may engage in direct or indirect self-harm behaviors as a way to temporarily relieve these negative emotions.

Field observations by the researchers also revealed that boys and girls lack the communication skills necessary for building positive relationships. This lack of training in the family, school, and other educational environments can result in adolescents facing challenges that require emotional management, problem-solving, and decision-making skills. Additionally, providing parenting education to familiarize parents with adolescents’ unique emotional and social characteristics can lead to a greater understanding of their adolescent children and promote their mental and psychological well-being within the family.

Attachment theories highlight the importance of parent-child relationships in shaping personality and behavior and emphasize the need for emotional support and attention from caregivers from birth. A lack of a suitable emotional climate in the family can cause a teenager to withdraw from family relationships during adolescence. Conversely, teenagers who perceive themselves as having a place and value within the family and experience a sense of security and peace are less likely to engage in self-harm behavior. Thus, the emotional climate of the family has a significant impact on harmful behavior in teenagers. The findings of the present study are in line with those of previous research, highlighting the importance of a supportive and positive family environment in preventing self-harm behavior in adolescents [10, 17].

Conclusion

Identifying and treating depression can be effective in reducing self-harm behaviors. Adjusting educational demands and setting realistic expectations for students can also foster their interest in school. A favorable emotional climate in the family can contribute to a student’s mental peace, concentration, and vitality, which can also reduce the likelihood of self-harm. To prevent self-harm behaviors in adolescents, it is crucial to improve interpersonal relationships within the family, interpersonal relationships at school, and academic performance.

This research, like other research in the humanities, has also been associated with limitations, such as the use of questionnaires, self-assessment, cross-sectional research, the implementation of research on a group, a specific place and time, the lack of control over the cause-and-effect relationships of variables and the method of conducting the research. Therefore, the internal and external validity of the current research should be handled with caution. However, the researchers focused on predicting and identifying these factors as much as possible and using the necessary plan to reduce them.

It is suggested that other researchers investigate the issue more deeply and more accurately in future research through a case study in one or more families and to identify factors affecting self-harming behaviors in other groups at risk, including boys. Also, it is suggested that effective research be conducted in the family and school environment to reduce family tensions and improve the psychosocial climate of the school.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.HUMS.REC.1401.261). The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, funding administration and writing Moosa Javdan; Methodology, Review and editing: Abdolvahab Samavi Abdolvahab Samavi; Investigation: Beheshteh AhmadiTeifakani; Data collection: All authors; Data analysis: Moosa Javdan and Abdolvahab Samavi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the residents of Benoband Village, participating students, parents, and school teachers.

References

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh AC, et al. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet. 2012; 379(9826):1630-40. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5] [PMID]

- Dorn LD, Hostinar CE, Susman EJ, Pervanidou P. Conceptualizing puberty as a window of opportunity for impacting health and well‐being across the life span. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2019; 29(1):155-76. [DOI:10.1111/jora.12431] [PMID]

- Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2013; 9:449-61. [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S39776] [PMID]

- Gillies D, Christou MA, Dixon AC, Featherston OJ, Rapti I, Garcia-Anguita A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of self-harm in adolescents: Meta-analyses of community-based studies 1990-2015. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018; 57(10):733-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.018] [PMID]

- Cesar Riani Costa L, Martins Gabriel I, Oliveira WA, Hortense P, López de Dicastillo Sáinz de Murieta O, Carlos DM. Non-suicidal self-injury experiences for adolescents who self-injured: Contributions of Winnicott’s psychoanalytic theory. Texto & Contexto Enfermagem. 2021, 30: e20190382. [DOI: 10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2019-0382]

- Vafaei T, Samavi SA, Whisenhunt JL, Najarpourian S. An investigation of self-injury in female adolescents: A qualitative study. Quality & Quantity. 2023; 1-24. [DOI:10.1007/s11135-023-01632-9] [PMID]

- Smith L, Jackson SE, Vancampfort D, Jacob L, Firth J, Grabovac I, et al. Sexual behavior and suicide attempts among adolescents aged 12-15 years from 38 countries: A global perspective. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 287:112564. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112564] [PMID]

- Azasu EK, Joe S. Correlates of suicide among middle and high school students in Ghana. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2023; 72(5), S59-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.09.036] [PMID]

- Sim L, Adrian M, Zeman J, Cassano M, Friedrich WN. Adolescent deliberate self‐harm: Linkages to emotion regulation and family emotional climate. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009; 19(1):75-91. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00582.x]

- Fortune S, Cottrell D, Fife S. Family factors associated with adolescent self‐harm: A narrative review. Journal of Family Therapy. 2016; 38(2):226-56. [DOI:10.1111/1467-6427.12119]

- Duffy ME, Twenge JM, Joiner TE. Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among US undergraduates, 2007-2018: Evidence from two national surveys. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019; 65(5):590-8.[DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033] [PMID]

- Klemera E, Brooks FM, Chester KL, Magnusson J, Spencer N. Self-harm in adolescence: Protective health assets in the family, school and community. International Journal of Public Health. 2017; 62(6):631-8. [DOI:10.1007/s00038-016-0900-2] [PMID]

- Greenwood L, Kelly C. A systematic literature review to explore how staff in schools describe how a sense of belonging is created for their pupils. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2019; 24(1):3-19. [DOI:10.1080/13632752.2018.1511113]

- Fisher LB, Overholser JC, Ridley J, Braden A, Rosoff C. From the outside looking in: Sense of belonging, depression, and suicide risk. Psychiatry. 2015; 78(1), 29-41. [DOI:10.1080/00332747.2015.1015867] [PMID]

- Lee E, Reynolds KJ, Subasic E, Bromhead D, Lin H, Marinov V, et al. Development of a dual school climate and school identification measure-student (SCASIM-St). Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2017; 49, 91-106. [DOI:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.003]

- Yang Y, Jiang J. Influence of family structure on adolescent deviant behavior and depression: The mediation roles of parental monitoring and school connectedness. Public Health. 2023; 217:1-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2023.01.013] [PMID]

- Pitkänen J, Bijlsma MJ, Remes H, Aaltonen M, Martikainen P. The effect of low childhood income on self-harm in young adulthood: Mediation by adolescent mental health, behavioral factors and school performance. SSM-Population Health. 2021; 13:100756. [DOI:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100756] [PMID]

- Dorol-Beauroy-Eustache O, Mishara BL. Systematic review of risk and protective factors for suicidal and self-harm behaviors among children and adolescents involved with cyberbullying. Preventive Medicine. 2021; 152(Pt 1):106684. [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106684] [PMID]

- Green SB. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1991; 26(3):499-510. [DOI:10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7] [PMID]

- Brooks S. The Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS). Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology News. 2004; 9(5):4-6. [DOI:10.1521/capn.9.5.4.52044]

- Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001; 23(4):253-63. [DOI:10.1023/A:1012779403943]

- Payvastehgar M. [The rate of deliberate self- harming in girls students and relationship with loneliness & Attachment styles (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Studies. 2013; 9(3):29-52. [DOI:10.22051/psy.2013.1750]

- Javdan M. The effect of family emotional-psychological atmosphere on suicide attempt of adolescents referred to hospitals in Hormozgan Province. Journal of Family Relations Studies. 2022; 2(6):38-46. [DOI:10.22098/JHRS.2022.9519.1017]

- Ghodsi A, Sarihi N, Aghyoosefi A. [Relationship between achievement motivation and early maladaptive schemas and family emotional atmosphere (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2014; 8(4):111-31. [Link]

- Imamgholivand F, Kadivar P, Sharifi H. [The prediction of happiness and creativity based on the school climate by mediating the Educational Engagement and the emotional-social competence of high school female students (Persian)]. Educational Psychology. 2019; 15(52):155-81. [DOI:10.22054/jep.2019.34325.2350]

- Pham LB, Taylor SE. From thought to action: Effects of process-versus outcome-based mental simulations on performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999; 25(2):250-60. [DOI:10.1177/0146167299025002010]

- Mozafari N, Bagherian F, ZadeMohammadi A, Heidari M. [Identifying what and how high-risk behaviors in adolescents engaged in high-risk behaviors: A phenomenological study (Persian)]. Scientific Quarterly Research on Addiction. 2020; 14(56):199-224. [DOI:10.29252/etiadpajohi.14.56.199]

- Aggarwal S, Patton G, Reavley N, Sreenivasan SA, Berk M. Youth self-harm in low-and middle-income countries: systematic review of the risk and protective factors. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2017; 63(4):359-75. [DOI:10.1177/0020764017700175] [PMID]

- Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, Moran P, O'Connor RC, Tilling K, et al. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: A population-based birth cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019; 6(4), 327-37. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30030-6] [PMID]

- Chen R, Liu J, Cao X, Duan S, Wen S, Zhang S, et al. The relationship between mobile phone use and suicide-related behaviors among adolescents: The mediating role of depression and interpersonal problems. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 269:101-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.128] [PMID]

- Lundh LG, Wångby-Lundh M, Paaske M, Ingesson S, Bjärehed J. Depressive symptoms and deliberate self-harm in a community sample of adolescents: A prospective study. Depression Research and Treatment. 2011; 2011:935871. [DOI:10.1155/2011/935871] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2023/06/18 | Accepted: 2023/09/5 | Published: 2024/05/1

Received: 2023/06/18 | Accepted: 2023/09/5 | Published: 2024/05/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |