Volume 16, Issue 1 (Jan & Feb 2026)

J Research Health 2026, 16(1): 61-70 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Akanda K M, Mehjabin S, Barik A, Islam R, Islam N, Rana M, et al . Investigating the Cause and Management of Diarrhea in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh: A Retrospective Study. J Research Health 2026; 16 (1) :61-70

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2387-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2387-en.html

Khokon Miah Akanda1

, Sanzia Mehjabin2

, Sanzia Mehjabin2

, Abdul Barik2

, Abdul Barik2

, Rafiul Islam2

, Rafiul Islam2

, Nazmul Islam2

, Nazmul Islam2

, Masud Rana2

, Masud Rana2

, Razia Sultana2

, Razia Sultana2

, Ashik Mosaddik3

, Ashik Mosaddik3

, Masud Parvez4

, Masud Parvez4

, Sanzia Mehjabin2

, Sanzia Mehjabin2

, Abdul Barik2

, Abdul Barik2

, Rafiul Islam2

, Rafiul Islam2

, Nazmul Islam2

, Nazmul Islam2

, Masud Rana2

, Masud Rana2

, Razia Sultana2

, Razia Sultana2

, Ashik Mosaddik3

, Ashik Mosaddik3

, Masud Parvez4

, Masud Parvez4

1- Department of Pharmacy, School of Science and Technology, Varendra University, Rajshahi, Bangladesh. & Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, University of Asia Pacific, Dhaka, Bangladesh , khokon.vu@gmail.com

2- Department of Pharmacy, School of Science and Technology, Varendra University, Rajshahi, Bangladesh.

3- Pro Vice Chancellor, East West University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

4- Department of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Georgia, Athens, USA.

2- Department of Pharmacy, School of Science and Technology, Varendra University, Rajshahi, Bangladesh.

3- Pro Vice Chancellor, East West University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

4- Department of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Georgia, Athens, USA.

Full-Text [PDF 1674 kb]

(88 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2416 Views)

Full-Text: (2 Views)

Introduction

Diarrheal diseases continue to account for substantial morbidity and mortality globally, particularly in countries where clean water access and proper sanitation remain limited. In Bangladesh, despite expanded coverage of basic health services, diarrhea persists as a common clinical complaint and a frequent cause of hospital visits, especially in rural settings. Despite global efforts to improve water and sanitation infrastructure, waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea, remain a significant public health concern worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 4.4 billion people lack access to safely managed drinking water, and over 2 billion people still lack access to basic sanitation services [1, 2]. Globally, diarrheal diseases are the second leading cause of death among children under five, causing approximately 525 000 deaths annually [3]. The burden of diarrheal diseases is most pronounced in areas with poor sanitation and inadequate access to safe water. A report by the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF, 2020) estimated that nearly 80% of all diarrheal diseases in developing countries result from the consumption of contaminated water and insufficient sanitation and hygiene practices [4, 5]. This issue is particularly prevalent in rural areas of South Asia, including Bangladesh, where access to safe drinking water and sanitation remains a significant challenge [1].

In Bangladesh, despite improvements in water and sanitation infrastructure, the prevalence of waterborne diseases, particularly diarrhea, remains high. This situation is exacerbated by the heavy reliance on unprotected water sources, such as tube wells, ponds, and rivers, which are prone to contamination, especially during the rainy season. Research indicates that nearly 30% of rural households in Bangladesh still rely on unsafe water sources, contributing significantly to the ongoing health crisis [6]. Furthermore, a lack of hygiene education and poor sanitation practices exacerbate the spread of waterborne diseases in rural areas. Bangladesh has made considerable strides in improving access to drinking water, with approximately 98% of the population now accessing to improved water sources. However, sanitation coverage remains low, with only about 61% of the population having access to improved sanitation [7]. In rural regions, such as Rajshahi City, Bangladesh, the situation remains particularly dire. Many households in Rajshahi City continue to rely on unprotected water sources, and the lack of proper sanitation infrastructure contributes to the contamination of drinking water and poor hygiene [8]. Mou et al. (2023) found that rural households in Rajshahi City are vulnerable to outbreaks of diarrheal diseases due to poor water quality and inadequate sanitation [9].

Recent studies have also indicated that water quality remains a significant issue despite increased access to water sources. According to Mou et al. (2023), approximately 40% of rural water sources in Bangladesh are contaminated with fecal matter, which significantly increases the risk of waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea. Moreover, inadequate waste disposal and sanitation facilities contribute to the contamination of water sources in densely populated rural areas [9]. The reliance on untreated water sources, combined with insufficient sanitation systems, continues to facilitate the spread of pathogens that cause diarrheal diseases, thus maintaining high morbidity and mortality rates in rural areas. One key factor in the persistence of diarrheal diseases is the lack of proper hygiene. The WHO reports that nearly 50% of people in rural Bangladesh do not wash their hands with soap after defecating, a key factor in the spread of waterborne diseases [5]. Studies have shown that handwashing with soap can reduce the incidence of diarrheal diseases by up to 40% [10]. This highlights the importance of hygiene education as part of any intervention to reduce waterborne diseases in the region. Diarrheal diseases in Bangladesh are caused by a variety of pathogens, including bacteria, such as Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli, and viruses, such as rotavirus. These pathogens are transmitted through contaminated water, food, and surfaces, further exacerbating the public health crisis. Despite the availability of vaccines for some of these pathogens (e.g. rotavirus), the high burden of diarrhea persists due to the widespread contamination of water sources [11]. Oral rehydration therapy (ORS) remains the cornerstone of treatment for diarrheal diseases, and its use has reduced dehydration-related deaths in Bangladesh. However, antibiotic resistance, particularly among pathogens, such as Shigella and Vibrio cholerae, is a growing concern [12, 13]. The misuse of antibiotics in rural areas, where access to healthcare is limited, has contributed to the rise in antimicrobial resistance, making the treatment of diarrheal diseases more complex and less effective [14].

This study aimed to investigate the causes, management strategies, and treatment outcomes of diarrhea in Rajshahi City. By focusing on water sources, sanitation practices, and hygiene education, this study provides actionable insights into the risk factors associated with diarrheal diseases. The findings will contribute to public health strategies to reduce the prevalence of waterborne diseases, improve sanitation infrastructure, and promote better hygiene practices in rural Bangladesh. Improving water quality, sanitation, and hygiene is crucial for controlling the spread of diarrheal diseases, and this research aligns with global efforts to achieve sustainable development goal 6, which aims to ensure universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030 [15, 16].

Methods

Sampling

Data were collected from patients who presented to the hospital with diarrhea. The data collectors waited at the hospital and convinced patients receiving anti-diarrheal therapy to collect information from their prescriptions, which they then provided to the interviewers, to participate in the interview session. The data collectors also interviewed the patients about their lifestyles. Sometimes data collectors visited the patients’ homes and collected the survey.

Data collection

Before the fieldwork began, field interviewers received proper training in data gathering. To ensure data reliability, several monitors were used to oversee data collection. Furthermore, the individual researcher visited the field regularly to ensure that data collection was performed as specified. The questionnaire was written in English and translated into Bengali by data collectors for individuals whose first language is Bengali. The data collectors translated the Bengali responses supplied by respondents into English in the same way. During this investigation, each patient provided written permission. Due to insufficient information, a few questions were excluded from the data analysis. Using Microsoft Excel software, version 2013, descriptive statistics were applied to the collected data and represented as a Table and a Figure.

Setting and design

A total of 643 patients were interviewed directly in an experimental investigation using a self-designed semi-structured questionnaire. The data were collected in Rajshahi City, primarily from hospitals, with some data also collected through direct patient visits. The Rajshahi district was chosen to collect data for ten months, from April 2019 to February 2020. Rajshahi City is in the northwestern part of Bangladesh (Figure 1a). It serves as the divisional headquarters and administrative district of Rajshahi Division, which has a population of 2 595 197 people. It has a total area of 2,407.01 km² (929.35 sq mi) and is situated on the northern bank of the Padma River [17].

.PNG)

Results

Basic patient characteristics

A total of 643 patients diagnosed with diarrhea were interviewed over nine months in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh, to gather demographic and epidemiological data. The study revealed a distinct gender imbalance, with 446 males (69.36%) and 197 females (30.64%) affected. This gender disparity may reflect differences in exposure risks, occupational patterns, or healthcare-seeking behavior, suggesting that males in this region may either be more vulnerable to diarrheal pathogens due to outdoor activities and water exposure or more likely to present at healthcare facilities.

Age distribution data indicated that the majority of patients were in the 21–40-year age group, with the 21–30 and 31–40 brackets comprising 24.88% and 28.46% of the total sample, respectively. This prevalence among young and middle-aged adults is noteworthy, as it contrasts with global trends where children under five are typically the most affected group. This suggests that in Rajshahi City, environmental or behavioral exposures related to work, diet, and hygiene among adults may play a more dominant role.

When assessing disease recurrence, 56.30% of patients reported experiencing diarrhea for the first time. However, 21.62% had contracted it a second time, 8.40% a third time, and 13.68% more than three times. These figures underscore the recurring nature of diarrheal illnesses in the region, indicating ongoing exposure to contaminated water, inadequate sanitation, or a lack of behavioral change following earlier episodes. This pattern suggests that many individuals remain at risk even after recovery, highlighting a gap in long-term prevention strategies.

Additionally, data on intra-household transmission showed that in 80% of cases, only the individual patient was affected. However, in 13% of households, one additional family member also contracted diarrhea, and in 7% of cases, two or more family members were affected. These findings suggest a moderate level of household transmission or shared exposure to contaminated water and food sources, which may be exacerbated by communal practices such as shared meals or water storage containers.

Collectively, the demographic profile indicates that diarrhea in Rajshahi City predominantly affects economically active adults and men, with recurring patterns suggesting persistent environmental risks and a limited effectiveness of current health education and interventions. These results underscore the importance of targeted public health strategies that focus not only on infrastructure improvements but also on sustained community-level awareness and behavioral change. Further demographic breakdowns, including occupation, educational background, and residence (urban vs rural), would be valuable in future studies to refine intervention strategies.

Patient’s hygiene

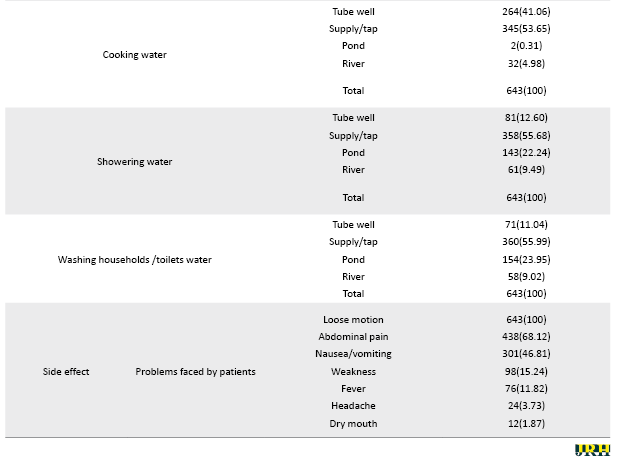

This study assessed patients’ hygiene behaviors, with a particular focus on the sources of water used for daily activities, including drinking, cooking, bathing, and sanitation. The findings highlight significant dependence on specific water sources, reflecting both infrastructural limitations and potential exposure risks to waterborne pathogens.

For drinking purposes, tube well water was the most commonly used source, reported by 78.07% of patients. This heavy reliance on tube wells indicates their central role in household water supply in Rajshahi City. However, despite being considered an improved water source, tube wells can become contaminated if not properly sealed or if located near latrines and open drainage systems. Only a small fraction of participants (2.64%) used filtered water, and 20.53% used supply/tap water for drinking, raising concerns about the perception of safety and the accessibility of treated water.

In terms of cooking, both supply water (53.65%) and tube healthy water (41.06%) were widely used. This dual reliance suggests that while households may favor supplying water for convenience or availability, tube wells remain a common alternative. Notably, a small proportion (4.98%) also used river water, and an even smaller group used pond water (0.31%), both of which pose significant health risks if untreated.

When it comes to personal hygiene activities, such as showering and washing household tools or toilets, water is supplied by the majority of participants: 55.68% for showering and 55.99% for cleaning. However, a substantial number of patients also reported using pond and river water for these activities (22.24% and 9.49%, respectively, for showering; 23.95% and 9.02%, respectively, for washing/toileting). These alternative water sources are likely unprotected and can be easily contaminated with fecal matter, thereby increasing the risk of infection through skin contact or surface contamination.

Tube-well water was also used for showering (12.60%) and cleaning (11.04%), reinforcing its role in multipurpose domestic use. The use of pond and river water for hygiene tasks signals not only environmental contamination but also potential economic or supply-related constraints that limit access to safer water (Table 1).

.PNG)

These findings emphasize the complex water-use behaviors in rural Rajshahi City and underscore the need for improved water infrastructure and hygiene education. Although some households perceive their water sources as safe, using untreated or unsafe sources for daily hygiene significantly elevates the risk of diarrheal disease transmission. Therefore, public health interventions should focus on promoting safe water storage, advocating household-level water treatment methods, and ensuring that improved water sources are not compromised by environmental exposure or poor maintenance.

Most patients in the study reported that their family members were unaffected by the diarrhea; however, a few cases showed that multiple family members were also impacted (Figure 1a). Regarding the safety of their drinking water, over 80% of participants perceived their water source as safe, while the remaining participants considered their water source to be moderately safe. A tiny proportion felt their water source was unsafe (Figure 1b). For cooking water, the majority of respondents considered it moderately safe, with around 40% reporting that their cooking water was entirely secure. Tube-healthy water was frequently recommended as a safe option, while tap or supply water was viewed as moderately safe (Figure 1c). However, when it came to water used for showering and toileting, most patients considered it moderately safe, although over 30% perceived their water source as unsafe (Figures 1d and 2a). Only about one in ten participants believed their showering and toileting water sources were safe.

Sanitation practices in the region must be improved to reduce the spread of diarrheal diseases. One essential measure is the use of pit latrines for the secure disposal of human waste. Ensuring that restrooms are correctly used, regularly cleaned, and disinfected daily is critical. Furthermore, handwashing stations should be installed near restrooms, equipped with soap and an adequate water supply to encourage proper hygiene practices and minimize the risk of contamination [9, 18]. In this study, approximately 50% of participants reported using soap after toileting. In contrast, the remaining patients used alternatives such as hand wash, ash, or just water (Figure 2b). This indicates a significant gap in the adoption of best hygiene practices. In addition, several techniques, both physical (such as boiling) and chemical methods (such as filtration or disinfection), are available for purifying water; however, only 12-18% of participants reported using these methods (Figures 2c and 2d). This highlights the need for increased education and access to simple water-purification techniques, as many patients do not use effective measures to ensure the safety of their drinking water.

.PNG)

Therapy and effects

The patients in the study presented with a range of symptoms, including loose stools, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, weakness, fever, and headaches (Table 1). To address these symptoms and manage dehydration, patients were administered salt and mineral supplements. In addition, various medications were prescribed based on the nature of the symptoms. Antibiotics were used to treat bacterial infections, while antiemetic drugs were administered to alleviate nausea and vomiting. Antispasmodics, such as Tiemonium methyl sulfate, were prescribed to relieve abdominal cramps, and opioid antagonists, such as loperamide, were used to control diarrhea. Additionally, Table 2 outlines the use of several other medications, including H2-receptor blockers (such as ranitidine) and proton pump inhibitors (such as omeprazole and pantoprazole) to manage symptoms related to stomach acid and discomfort. Pain relievers, including paracetamol, were also prescribed to alleviate pain and fever, and vitamin supplements were provided to support the patient’s recovery. This comprehensive treatment regimen aimed to address multiple aspects of the disease and provide symptomatic relief to patients.

.PNG)

Discussion

Sanitation can be improved by utilizing pit latrines for the secure disposal of human waste, ensuring restrooms are correctly used, maintaining clean toilets, and disinfecting them daily. Additionally, handwashing stations near restrooms are equipped with soap and sufficient water [18]. Diarrhea, cholera, and typhoid are strongly associated with poverty and unsanitary conditions. Inadequate housing, overcrowding, a lack of clean water and sanitary excrement disposal, and cohabitation with domestic animals that may spread human illnesses are all associated with poverty. This study highlights the critical relationship between unsafe water sources and inadequate sanitation in the prevalence of diarrhea in Rajshahi City. The findings confirm that water quality is a key factor in the spread of diarrhea, with a high proportion of patients relying on tube well water, which is often unprotected and potentially contaminated. This aligns with the study of Hasan et al. (2019) and other studies that have found similar patterns in rural Bangladesh, where unsafe water sources contribute significantly to diarrheal diseases [6, 9]. Several practical recommendations emerge from this study’s findings. Promoting safe water practices, such as boiling or filtering water before consumption, is essential. Only 2.64% of patients in this study reported using filtered water, which is significantly lower compared to global standards for safe drinking water [1]. This is similar to studies conducted in other regions, such as Cameroon, where only 13% of people used filtered water, while many relied on unprotected water sources [7]. To mitigate this, efforts should be made to ensure access to safe water treatments, such as filtration or chemical disinfectants, especially in rural Bangladesh, where access to clean water remains limited [19].

The study also emphasizes the need for handwashing stations equipped with soap and water near toilets. The WHO (2020) emphasizes that proper handwashing with soap is one of the most effective measures to reduce the transmission of diarrheal diseases [2]. A similar study conducted in Pakistan by Qureshi et al. (2011) found that improved handwashing practices significantly reduced the incidence of diarrhea in rural communities [20]. The findings of this study are consistent with research conducted in other regions with similar water and sanitation challenges. A survey by Fewtrell et al. (2005) found that rural areas in Bangladesh, including Rajshahi City, face significant challenges in ensuring safe access to water, with a large proportion of households relying on unprotected water sources [11]. Similarly, in rural Cameroon, Fonyuy (2014) reported that 43% of households relied on spring water, and 23% used river water, both of which were highly contaminated and contributed to the spread of waterborne diseases [19]. Rosa et al. (2010) found in Guatemala that boiling water effectively reduced the incidence of waterborne diseases by 86.2%. In this study, only 18.97% of participants used physical methods, such as boiling, while 12.13% used chemicals for water purification. This highlights the need for further education and the dissemination of simple, cost-effective water purification methods, as most patients do not adhere to the recommended water safety practices [21, 22].

A comparison with the findings of a recent study showed that only 50.70% of participants reported using soap after toileting, far below expected levels of handwashing with soap. This finding is consistent with results from a non-randomized trial in rural Bangladesh, where households with the highest handwashing uptake were those that received handwashing promotion along with some sort of product and equipment support versus households that received handwashing promotion only [23].

This study offers valuable insights into the hygiene practices and water usage of patients with diarrhea in Rajshahi City, highlighting the ongoing water quality issues in the region. However, the study’s reliance on convenience sampling and its limited geographic scope in Rajshahi City may limit the generalizability of the results. Similar studies in different districts of Bangladesh, such as those by Garbern et al. (2020) could provide broader insights into the waterborne disease burden in rural areas [13]. A significant limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to make causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term effects of water quality and sanitation interventions [24]. Furthermore, the study did not fully address the potential impact of climate change, which has been shown to exacerbate water contamination and increase the incidence of diarrhea during extreme weather events [25]. Another limitation is the exclusion of some data due to incomplete responses, which could have led to an underrepresentation of certain demographic groups. This is a common issue in studies that rely on self-reported data, highlighting the need for more robust data collection methods in future studies [10].

Conclusion

This study highlights the relationship between unsafe water sources, inadequate sanitation, and the high prevalence of diarrhea in Rajshahi City. Despite improvements in water access, the continued reliance on unprotected water sources, such as tube wells, remains a significant public health concern. These findings underscore the need for practical interventions, including promoting water purification methods, enhancing sanitation facilities, and increasing handwashing education. Improving access to safe water, ensuring proper sanitation, and educating communities on hygiene practices are crucial steps to reduce waterborne diseases. While the study faced limitations, such as the reliance on convenience sampling, it provides valuable insights that can guide public health strategies in rural Bangladesh. These findings align with global health efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal of universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030. Future research should assess the long-term impact of household water purification methods, the effectiveness of hygiene education programs, and the role of climate change in the transmission of waterborne diseases. Additionally, studies should explore regional variations in disease prevalence, the impact of sanitation improvement, and factors influencing hygiene and safe water usage. In conclusion, addressing water quality and sanitation issues is vital for reducing diarrhea and improving public health in rural Bangladesh.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Varendra University, Rajshahi, Bangladesh (Code: VU/Pharm/CAS-ETA/2019/04/16).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, and supervision, manuscript finalization: Masud Parvez; Data collection: Abdul Barik, Rafiul Islam, Nazmul Islam, Masud Rana and Razia Sultana; Manuscript draft: Sanzia Mehjabin; Data analysis, manuscript review, and edit: Khokon Miah Akanda; Manuscript review and edit: Ashik Mosaddik.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashik Mosaddik, Department of Pharmacy, Rajshahi University, for his support throughout the study.

References

Diarrheal diseases continue to account for substantial morbidity and mortality globally, particularly in countries where clean water access and proper sanitation remain limited. In Bangladesh, despite expanded coverage of basic health services, diarrhea persists as a common clinical complaint and a frequent cause of hospital visits, especially in rural settings. Despite global efforts to improve water and sanitation infrastructure, waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea, remain a significant public health concern worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 4.4 billion people lack access to safely managed drinking water, and over 2 billion people still lack access to basic sanitation services [1, 2]. Globally, diarrheal diseases are the second leading cause of death among children under five, causing approximately 525 000 deaths annually [3]. The burden of diarrheal diseases is most pronounced in areas with poor sanitation and inadequate access to safe water. A report by the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF, 2020) estimated that nearly 80% of all diarrheal diseases in developing countries result from the consumption of contaminated water and insufficient sanitation and hygiene practices [4, 5]. This issue is particularly prevalent in rural areas of South Asia, including Bangladesh, where access to safe drinking water and sanitation remains a significant challenge [1].

In Bangladesh, despite improvements in water and sanitation infrastructure, the prevalence of waterborne diseases, particularly diarrhea, remains high. This situation is exacerbated by the heavy reliance on unprotected water sources, such as tube wells, ponds, and rivers, which are prone to contamination, especially during the rainy season. Research indicates that nearly 30% of rural households in Bangladesh still rely on unsafe water sources, contributing significantly to the ongoing health crisis [6]. Furthermore, a lack of hygiene education and poor sanitation practices exacerbate the spread of waterborne diseases in rural areas. Bangladesh has made considerable strides in improving access to drinking water, with approximately 98% of the population now accessing to improved water sources. However, sanitation coverage remains low, with only about 61% of the population having access to improved sanitation [7]. In rural regions, such as Rajshahi City, Bangladesh, the situation remains particularly dire. Many households in Rajshahi City continue to rely on unprotected water sources, and the lack of proper sanitation infrastructure contributes to the contamination of drinking water and poor hygiene [8]. Mou et al. (2023) found that rural households in Rajshahi City are vulnerable to outbreaks of diarrheal diseases due to poor water quality and inadequate sanitation [9].

Recent studies have also indicated that water quality remains a significant issue despite increased access to water sources. According to Mou et al. (2023), approximately 40% of rural water sources in Bangladesh are contaminated with fecal matter, which significantly increases the risk of waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea. Moreover, inadequate waste disposal and sanitation facilities contribute to the contamination of water sources in densely populated rural areas [9]. The reliance on untreated water sources, combined with insufficient sanitation systems, continues to facilitate the spread of pathogens that cause diarrheal diseases, thus maintaining high morbidity and mortality rates in rural areas. One key factor in the persistence of diarrheal diseases is the lack of proper hygiene. The WHO reports that nearly 50% of people in rural Bangladesh do not wash their hands with soap after defecating, a key factor in the spread of waterborne diseases [5]. Studies have shown that handwashing with soap can reduce the incidence of diarrheal diseases by up to 40% [10]. This highlights the importance of hygiene education as part of any intervention to reduce waterborne diseases in the region. Diarrheal diseases in Bangladesh are caused by a variety of pathogens, including bacteria, such as Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli, and viruses, such as rotavirus. These pathogens are transmitted through contaminated water, food, and surfaces, further exacerbating the public health crisis. Despite the availability of vaccines for some of these pathogens (e.g. rotavirus), the high burden of diarrhea persists due to the widespread contamination of water sources [11]. Oral rehydration therapy (ORS) remains the cornerstone of treatment for diarrheal diseases, and its use has reduced dehydration-related deaths in Bangladesh. However, antibiotic resistance, particularly among pathogens, such as Shigella and Vibrio cholerae, is a growing concern [12, 13]. The misuse of antibiotics in rural areas, where access to healthcare is limited, has contributed to the rise in antimicrobial resistance, making the treatment of diarrheal diseases more complex and less effective [14].

This study aimed to investigate the causes, management strategies, and treatment outcomes of diarrhea in Rajshahi City. By focusing on water sources, sanitation practices, and hygiene education, this study provides actionable insights into the risk factors associated with diarrheal diseases. The findings will contribute to public health strategies to reduce the prevalence of waterborne diseases, improve sanitation infrastructure, and promote better hygiene practices in rural Bangladesh. Improving water quality, sanitation, and hygiene is crucial for controlling the spread of diarrheal diseases, and this research aligns with global efforts to achieve sustainable development goal 6, which aims to ensure universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030 [15, 16].

Methods

Sampling

Data were collected from patients who presented to the hospital with diarrhea. The data collectors waited at the hospital and convinced patients receiving anti-diarrheal therapy to collect information from their prescriptions, which they then provided to the interviewers, to participate in the interview session. The data collectors also interviewed the patients about their lifestyles. Sometimes data collectors visited the patients’ homes and collected the survey.

Data collection

Before the fieldwork began, field interviewers received proper training in data gathering. To ensure data reliability, several monitors were used to oversee data collection. Furthermore, the individual researcher visited the field regularly to ensure that data collection was performed as specified. The questionnaire was written in English and translated into Bengali by data collectors for individuals whose first language is Bengali. The data collectors translated the Bengali responses supplied by respondents into English in the same way. During this investigation, each patient provided written permission. Due to insufficient information, a few questions were excluded from the data analysis. Using Microsoft Excel software, version 2013, descriptive statistics were applied to the collected data and represented as a Table and a Figure.

Setting and design

A total of 643 patients were interviewed directly in an experimental investigation using a self-designed semi-structured questionnaire. The data were collected in Rajshahi City, primarily from hospitals, with some data also collected through direct patient visits. The Rajshahi district was chosen to collect data for ten months, from April 2019 to February 2020. Rajshahi City is in the northwestern part of Bangladesh (Figure 1a). It serves as the divisional headquarters and administrative district of Rajshahi Division, which has a population of 2 595 197 people. It has a total area of 2,407.01 km² (929.35 sq mi) and is situated on the northern bank of the Padma River [17].

.PNG)

Results

Basic patient characteristics

A total of 643 patients diagnosed with diarrhea were interviewed over nine months in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh, to gather demographic and epidemiological data. The study revealed a distinct gender imbalance, with 446 males (69.36%) and 197 females (30.64%) affected. This gender disparity may reflect differences in exposure risks, occupational patterns, or healthcare-seeking behavior, suggesting that males in this region may either be more vulnerable to diarrheal pathogens due to outdoor activities and water exposure or more likely to present at healthcare facilities.

Age distribution data indicated that the majority of patients were in the 21–40-year age group, with the 21–30 and 31–40 brackets comprising 24.88% and 28.46% of the total sample, respectively. This prevalence among young and middle-aged adults is noteworthy, as it contrasts with global trends where children under five are typically the most affected group. This suggests that in Rajshahi City, environmental or behavioral exposures related to work, diet, and hygiene among adults may play a more dominant role.

When assessing disease recurrence, 56.30% of patients reported experiencing diarrhea for the first time. However, 21.62% had contracted it a second time, 8.40% a third time, and 13.68% more than three times. These figures underscore the recurring nature of diarrheal illnesses in the region, indicating ongoing exposure to contaminated water, inadequate sanitation, or a lack of behavioral change following earlier episodes. This pattern suggests that many individuals remain at risk even after recovery, highlighting a gap in long-term prevention strategies.

Additionally, data on intra-household transmission showed that in 80% of cases, only the individual patient was affected. However, in 13% of households, one additional family member also contracted diarrhea, and in 7% of cases, two or more family members were affected. These findings suggest a moderate level of household transmission or shared exposure to contaminated water and food sources, which may be exacerbated by communal practices such as shared meals or water storage containers.

Collectively, the demographic profile indicates that diarrhea in Rajshahi City predominantly affects economically active adults and men, with recurring patterns suggesting persistent environmental risks and a limited effectiveness of current health education and interventions. These results underscore the importance of targeted public health strategies that focus not only on infrastructure improvements but also on sustained community-level awareness and behavioral change. Further demographic breakdowns, including occupation, educational background, and residence (urban vs rural), would be valuable in future studies to refine intervention strategies.

Patient’s hygiene

This study assessed patients’ hygiene behaviors, with a particular focus on the sources of water used for daily activities, including drinking, cooking, bathing, and sanitation. The findings highlight significant dependence on specific water sources, reflecting both infrastructural limitations and potential exposure risks to waterborne pathogens.

For drinking purposes, tube well water was the most commonly used source, reported by 78.07% of patients. This heavy reliance on tube wells indicates their central role in household water supply in Rajshahi City. However, despite being considered an improved water source, tube wells can become contaminated if not properly sealed or if located near latrines and open drainage systems. Only a small fraction of participants (2.64%) used filtered water, and 20.53% used supply/tap water for drinking, raising concerns about the perception of safety and the accessibility of treated water.

In terms of cooking, both supply water (53.65%) and tube healthy water (41.06%) were widely used. This dual reliance suggests that while households may favor supplying water for convenience or availability, tube wells remain a common alternative. Notably, a small proportion (4.98%) also used river water, and an even smaller group used pond water (0.31%), both of which pose significant health risks if untreated.

When it comes to personal hygiene activities, such as showering and washing household tools or toilets, water is supplied by the majority of participants: 55.68% for showering and 55.99% for cleaning. However, a substantial number of patients also reported using pond and river water for these activities (22.24% and 9.49%, respectively, for showering; 23.95% and 9.02%, respectively, for washing/toileting). These alternative water sources are likely unprotected and can be easily contaminated with fecal matter, thereby increasing the risk of infection through skin contact or surface contamination.

Tube-well water was also used for showering (12.60%) and cleaning (11.04%), reinforcing its role in multipurpose domestic use. The use of pond and river water for hygiene tasks signals not only environmental contamination but also potential economic or supply-related constraints that limit access to safer water (Table 1).

.PNG)

These findings emphasize the complex water-use behaviors in rural Rajshahi City and underscore the need for improved water infrastructure and hygiene education. Although some households perceive their water sources as safe, using untreated or unsafe sources for daily hygiene significantly elevates the risk of diarrheal disease transmission. Therefore, public health interventions should focus on promoting safe water storage, advocating household-level water treatment methods, and ensuring that improved water sources are not compromised by environmental exposure or poor maintenance.

Most patients in the study reported that their family members were unaffected by the diarrhea; however, a few cases showed that multiple family members were also impacted (Figure 1a). Regarding the safety of their drinking water, over 80% of participants perceived their water source as safe, while the remaining participants considered their water source to be moderately safe. A tiny proportion felt their water source was unsafe (Figure 1b). For cooking water, the majority of respondents considered it moderately safe, with around 40% reporting that their cooking water was entirely secure. Tube-healthy water was frequently recommended as a safe option, while tap or supply water was viewed as moderately safe (Figure 1c). However, when it came to water used for showering and toileting, most patients considered it moderately safe, although over 30% perceived their water source as unsafe (Figures 1d and 2a). Only about one in ten participants believed their showering and toileting water sources were safe.

Sanitation practices in the region must be improved to reduce the spread of diarrheal diseases. One essential measure is the use of pit latrines for the secure disposal of human waste. Ensuring that restrooms are correctly used, regularly cleaned, and disinfected daily is critical. Furthermore, handwashing stations should be installed near restrooms, equipped with soap and an adequate water supply to encourage proper hygiene practices and minimize the risk of contamination [9, 18]. In this study, approximately 50% of participants reported using soap after toileting. In contrast, the remaining patients used alternatives such as hand wash, ash, or just water (Figure 2b). This indicates a significant gap in the adoption of best hygiene practices. In addition, several techniques, both physical (such as boiling) and chemical methods (such as filtration or disinfection), are available for purifying water; however, only 12-18% of participants reported using these methods (Figures 2c and 2d). This highlights the need for increased education and access to simple water-purification techniques, as many patients do not use effective measures to ensure the safety of their drinking water.

.PNG)

Therapy and effects

The patients in the study presented with a range of symptoms, including loose stools, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, weakness, fever, and headaches (Table 1). To address these symptoms and manage dehydration, patients were administered salt and mineral supplements. In addition, various medications were prescribed based on the nature of the symptoms. Antibiotics were used to treat bacterial infections, while antiemetic drugs were administered to alleviate nausea and vomiting. Antispasmodics, such as Tiemonium methyl sulfate, were prescribed to relieve abdominal cramps, and opioid antagonists, such as loperamide, were used to control diarrhea. Additionally, Table 2 outlines the use of several other medications, including H2-receptor blockers (such as ranitidine) and proton pump inhibitors (such as omeprazole and pantoprazole) to manage symptoms related to stomach acid and discomfort. Pain relievers, including paracetamol, were also prescribed to alleviate pain and fever, and vitamin supplements were provided to support the patient’s recovery. This comprehensive treatment regimen aimed to address multiple aspects of the disease and provide symptomatic relief to patients.

.PNG)

Discussion

Sanitation can be improved by utilizing pit latrines for the secure disposal of human waste, ensuring restrooms are correctly used, maintaining clean toilets, and disinfecting them daily. Additionally, handwashing stations near restrooms are equipped with soap and sufficient water [18]. Diarrhea, cholera, and typhoid are strongly associated with poverty and unsanitary conditions. Inadequate housing, overcrowding, a lack of clean water and sanitary excrement disposal, and cohabitation with domestic animals that may spread human illnesses are all associated with poverty. This study highlights the critical relationship between unsafe water sources and inadequate sanitation in the prevalence of diarrhea in Rajshahi City. The findings confirm that water quality is a key factor in the spread of diarrhea, with a high proportion of patients relying on tube well water, which is often unprotected and potentially contaminated. This aligns with the study of Hasan et al. (2019) and other studies that have found similar patterns in rural Bangladesh, where unsafe water sources contribute significantly to diarrheal diseases [6, 9]. Several practical recommendations emerge from this study’s findings. Promoting safe water practices, such as boiling or filtering water before consumption, is essential. Only 2.64% of patients in this study reported using filtered water, which is significantly lower compared to global standards for safe drinking water [1]. This is similar to studies conducted in other regions, such as Cameroon, where only 13% of people used filtered water, while many relied on unprotected water sources [7]. To mitigate this, efforts should be made to ensure access to safe water treatments, such as filtration or chemical disinfectants, especially in rural Bangladesh, where access to clean water remains limited [19].

The study also emphasizes the need for handwashing stations equipped with soap and water near toilets. The WHO (2020) emphasizes that proper handwashing with soap is one of the most effective measures to reduce the transmission of diarrheal diseases [2]. A similar study conducted in Pakistan by Qureshi et al. (2011) found that improved handwashing practices significantly reduced the incidence of diarrhea in rural communities [20]. The findings of this study are consistent with research conducted in other regions with similar water and sanitation challenges. A survey by Fewtrell et al. (2005) found that rural areas in Bangladesh, including Rajshahi City, face significant challenges in ensuring safe access to water, with a large proportion of households relying on unprotected water sources [11]. Similarly, in rural Cameroon, Fonyuy (2014) reported that 43% of households relied on spring water, and 23% used river water, both of which were highly contaminated and contributed to the spread of waterborne diseases [19]. Rosa et al. (2010) found in Guatemala that boiling water effectively reduced the incidence of waterborne diseases by 86.2%. In this study, only 18.97% of participants used physical methods, such as boiling, while 12.13% used chemicals for water purification. This highlights the need for further education and the dissemination of simple, cost-effective water purification methods, as most patients do not adhere to the recommended water safety practices [21, 22].

A comparison with the findings of a recent study showed that only 50.70% of participants reported using soap after toileting, far below expected levels of handwashing with soap. This finding is consistent with results from a non-randomized trial in rural Bangladesh, where households with the highest handwashing uptake were those that received handwashing promotion along with some sort of product and equipment support versus households that received handwashing promotion only [23].

This study offers valuable insights into the hygiene practices and water usage of patients with diarrhea in Rajshahi City, highlighting the ongoing water quality issues in the region. However, the study’s reliance on convenience sampling and its limited geographic scope in Rajshahi City may limit the generalizability of the results. Similar studies in different districts of Bangladesh, such as those by Garbern et al. (2020) could provide broader insights into the waterborne disease burden in rural areas [13]. A significant limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to make causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term effects of water quality and sanitation interventions [24]. Furthermore, the study did not fully address the potential impact of climate change, which has been shown to exacerbate water contamination and increase the incidence of diarrhea during extreme weather events [25]. Another limitation is the exclusion of some data due to incomplete responses, which could have led to an underrepresentation of certain demographic groups. This is a common issue in studies that rely on self-reported data, highlighting the need for more robust data collection methods in future studies [10].

Conclusion

This study highlights the relationship between unsafe water sources, inadequate sanitation, and the high prevalence of diarrhea in Rajshahi City. Despite improvements in water access, the continued reliance on unprotected water sources, such as tube wells, remains a significant public health concern. These findings underscore the need for practical interventions, including promoting water purification methods, enhancing sanitation facilities, and increasing handwashing education. Improving access to safe water, ensuring proper sanitation, and educating communities on hygiene practices are crucial steps to reduce waterborne diseases. While the study faced limitations, such as the reliance on convenience sampling, it provides valuable insights that can guide public health strategies in rural Bangladesh. These findings align with global health efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal of universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030. Future research should assess the long-term impact of household water purification methods, the effectiveness of hygiene education programs, and the role of climate change in the transmission of waterborne diseases. Additionally, studies should explore regional variations in disease prevalence, the impact of sanitation improvement, and factors influencing hygiene and safe water usage. In conclusion, addressing water quality and sanitation issues is vital for reducing diarrhea and improving public health in rural Bangladesh.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Varendra University, Rajshahi, Bangladesh (Code: VU/Pharm/CAS-ETA/2019/04/16).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, and supervision, manuscript finalization: Masud Parvez; Data collection: Abdul Barik, Rafiul Islam, Nazmul Islam, Masud Rana and Razia Sultana; Manuscript draft: Sanzia Mehjabin; Data analysis, manuscript review, and edit: Khokon Miah Akanda; Manuscript review and edit: Ashik Mosaddik.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashik Mosaddik, Department of Pharmacy, Rajshahi University, for his support throughout the study.

References

- Bain R, Cronk R, Hossain R, Bonjour S, Onda K, Wright J, et al. Global assessment of exposure to faecal contamination through drinking water based on a systematic review. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2021; 19(8):917-27. [DOI:10.1111/tmi.12334] [PMID]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global water, sanitation and hygiene annual report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. [Link]

- Black RE, Perin J, Yeung D, Rajeev T, Miller J, Elwood SE, et al. Estimated global and regional causes of deaths from diarrhoea in children younger than 5 years during 2000–21: A systematic review and Bayesian multinomial analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2024; 12(6):e919-28. [Link]

- GBD 2021 Diarrhoeal Diseases Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific burden of diarrhoeal diseases, their risk factors, and aetiologies, 1990-2021, for 204 countries and territories: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2025; 25(5): 519–36. [DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00691-1]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Progress on drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene: 2020 update and SDG baselines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

- Hasan MK, Shahriar A, Jim KU. Water pollution in Bangladesh and its impact on public health. Heliyon. 2019; 5(8):e02145. [Link]

- Hossain M, Rahman M, Ahmed A. Challenges in achieving universal sanitation coverage: The case of rural Bangladesh. Journal of Water and Health. 2020; 18(4):561-574. [DOI:10.2166/wh.2020.059] [PMID]

- Ahmed I, Rabbi MB, Sultana S. Antibiotic resistance in Bangladesh: A systematic review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019; 80:54-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2018.12.017]

- Mou SI, Swarnokar SC, Ghosh S, Ridwan MT, Ishtiak KF. Assessment of drinking water quality served in different restaurants at Islam nagor road adjacent to Khulna university campus, Bangladesh. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection. 2023; 11(09):252–67. [Link]

- Curtis V, Danquah LO, Aunger R. The handwashing handbook. Stockholm: Global Handwashing Partnership; 2008 [Link]

- Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2005; 5(1):42-52. [DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8]

- Garbern SC, Chu TC, Gainey M, Kanekar SS, Nasrin S, Qu K, et al. Multidrug-resistant enteric pathogens in older children and adults with diarrhea in Bangladesh: Epidemiology and risk factors. Tropical Medicine and Health. 2021; 49(1):34. [DOI:10.1186/s41182-021-00327-x]

- Akanda MKM, Mehjabin S. Potential role of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in management of metabolic syndrome and chronic metabolic disease. In: Mishra N, Ashique S, Farid A, Garg A, editors. Synbiotics in metabolic disorder management. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2024. [DOI:10.1201/9781032702438-3]

- Tahiti SN, Hasan AN, Akter S, Anjum R, Akanda MK, Khuku AA, et al. Evaluation of pharmacological properties using in vitro and in vivo (Swiss albino male mice) model followed by isolation of ergosterol from the stem bark extract of Delonix regia (Bojer ex Hook.) Raf.(Fabaceae family). Trends in Phytochemical Research. 2025; 9(1):66-77. [DOI:10.71596/tpr.2025.195281]

- Sharma Waddington H, Masset E, Bick S, Cairncross S. Impact on childhood mortality of interventions to improve drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) to households: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2023; 20(4):e1004215. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1004215] [PMID]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Link]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Population & housing census-2011. Community report: Joypurhат 2011. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics; 2011. [Link]

- Hoque BA, Khanam S, Siddik MA, Ahmed S, Shipon AZ. Improving WASH Status and knowledge in the coastal areas of Bangladesh. Indonesian Journal of Geography. 2022; 54(3):463-70. [Link]

- Fonyuy BE. Prevalence of water borne diseases within households in the bamendankwe municipality-North West Cameroon. Journal of Biosafety & Health Education. 2014; 2(122):1-7. [DOI:10.4172/2332-0893.1000122]

- Qureshi EM, Khan AU, Vehra S. An investigation into the prevalence of water borne diseases in relation to microbial estimation of potable water in the community residing near River Ravi, Lahore, Pakistan. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2011; 5(8):595-607. [DOI:10.4314/ajest.v5i8.72055]

- Rosa G, Miller L, Clasen T. Microbiological effectiveness of disinfecting water by boiling in rural Guatemala. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010; 82(3):473-7. [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0320] [PMID]

- Akanda MK, Sultana R, Rana MM, Hossain MA, Barik SA, Islam MR,et al. Prevalence, causes, and management strategies of fungal diseases in Northern Regions of Bangladesh. Sciences of Pharmacy. 2024; 3(1):24-34. [DOI:10.58920/sciphar0301191]

- Siddiqua TJ, Choudhury N, Haque MA, Farzana FD, Ali M, Naz F, et al. Assessing the impact of a handwashing knowledge and practices program among poor households in rural Bangladesh: A cluster-randomized pre-post study. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2023; 109(3): 676-685. [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.21-0555] [PMID]

- Bhavnani D, Goldstick JE, Cevallos W, Trueba G, Eisenberg JN. Impact of rainfall on diarrheal disease risk associated with unimproved water and sanitation. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2014; 90(4):705-711. [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0371] [PMID]

- Cairncross S, Valdmanis V. Water supply, sanitation, and hygiene promotion. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries (2nd ed). Washington: The World Bank. 2006. [Link]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Disease Control

Received: 2023/07/16 | Accepted: 2025/08/2 | Published: 2026/01/1

Received: 2023/07/16 | Accepted: 2025/08/2 | Published: 2026/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |