Volume 15, Issue 2 (March & April 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(2): 117-126 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rastegar H, Jalili R, KhodayariZarnaq R. Subsidy Targeting and Food Security: Review and Presentation of Policy Options for Iran. J Research Health 2025; 15 (2) :117-126

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2407-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2407-en.html

1- Department of Health Policy and Management, Faculty of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

2- Department of Health Policy and Management, Faculty of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. ,rahimzarnagh@gmail.com

2- Department of Health Policy and Management, Faculty of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 588 kb]

(1357 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3447 Views)

Full-Text: (1876 Views)

Introduction

Nutrition is crucial for health, well-being, education, work efficiency, and economic growth. Nearly 795 million people globally suffer from malnutrition, predominantly in developing countries. Recognizing the significance of nutrition, public policies often reallocate resources or provide targeted subsidies to aid vulnerable groups [1-3]. After World War II, consumption subsidies, such as food subsidies and price controls, were introduced to address poverty and food insecurity, a practice that remains in effect [4]. Today, approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide benefit from food subsidies through programs, like Raskin in Indonesia, the public distribution system (PDS) in India, the Tamween program in Egypt and the supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) in the USA, which assist millions in obtaining essential food items [5, 6].

Iran has subsidized petroleum products, basic foodstuffs, medical supplies and utilities since 1980. These subsidies were initially implemented to mitigate the hardships of the eight-year war with Iraq and later to address post-war political and economic challenges. In 2010, the subsidies targeting act was enacted, reforming the payment system and phasing out subsidies for fuel, food, water, electricity, gas and other essentials. The legislation requires that a portion of the savings from subsidy reductions be redistributed to the public in both cash and non-cash forms [7, 8]. The primary aim of this law was to target subsidy payments to benefit the underprivileged segments of society. Following the implementation of this policy, there was a significant increase in household food expenditure, by 823 thousand Rials (approximately $6.36 based on the 2019 exchange rate), indicating that households used the additional cash to enhance their food purchases. However, the initial positive effects of the targeted subsidy reform have diminished over time due to inflation [9]. Since the implementation of the subsidy targeting law a decade ago, it has had a substantial impact on various macroeconomic indicators, such as inflation and income distribution. Sanctions have caused fluctuations in these factors, leading to significant increases in inflation rates between 2017 and 2019 (point-to-point inflation rates of 47.5%, 22% and 49%, respectively). This rise in living costs has led to a 38% increase in the poverty line in 2019 compared to 2018. The combination of high inflation and reduced per capita income due to negative economic growth in 2019 has adversely affected the well-being and living standards of Iranian households, especially those in lower income brackets [10]. Unfortunately, the law has not effectively improved food security for urban and rural households and has been associated with an increase in food insecurity [3, 11]. Lower socioeconomic status and food insecurity within households have become significant factors contributing to growth disorders in children [12]. In 2017, statistics showed that in deprived areas, the rates of underweight and stunted growth in children under five, as well as anemia in pregnant mothers, were more than double the national average. Additionally, deficiencies in vitamin A, zinc and iron were more common among mothers and children in these regions. Insufficient zinc and iron intake during the first 1000 days of life can lead to irreversible complications, such as stunted growth, impaired development, decreased IQ and a weakened immune system [13-15]. To address these challenges, targeted subsidies for food security are essential, given the limited resources available to support vulnerable populations. While physical payments for food may encourage consumption among various groups, cash payments do not necessarily lead to increased food intake [16]. The government has recently revised the subsidy payment method and is developing an electronic infrastructure for non-cash subsidy payments. This research aimed to leverage the experiences of various countries in indirect subsidy disbursement to enhance food security, providing valuable solutions to improve the health of Iranian households and maximize food security for vulnerable groups.

Methods

In our study, we applied the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s policy analytical framework, which serves as a systematic guide for identifying, analyzing, and prioritizing policies that promote health [17]. This framework encompasses several critical steps: Problem identification, policy solution exploration, policy option evaluation, prioritization, and strategy formulation for policy implementation. Under the subsidy targeting law, the government is permitted to allocate up to 50% of the net savings from this legislation towards cash and non-cash subsidies and the establishment of a comprehensive social security system. Social support programs are a key element of this system. It is proposed that, as an initial measure, subsidies should focus on food security, in line with the government’s plan to provide in-kind subsidies. Physical payments for food are expected to enhance consumption among targeted groups, thereby improving food security and public health.

In the second phase, we analyzed nutrition support programs in India, the United States and the United Kingdom to identify and characterize potential policy options. The rationale for selecting these countries includes India’s PDS, the world’s largest food subsidy network serving 800 million people [5, 18], the United States’ implementation of the majority of food subsidy programs [19] and the United Kingdom’s household food security data, which shows a high self-reported rate of food security in 2019–2020 [20]. Additionally, these nations have a long-standing tradition of food subsidies dating back to World War II [21]. In Iran, the nutritional support program for special groups, managed by various organizations, often encounters challenges and inconsistencies in food basket distribution, underscoring the need for targeted subsidies to ensure sustainable food security for those in need [22].

In the third stage, we evaluated policy options by reviewing the experiences of the selected countries and Iran’s current programs. Policy options were developed based on the identified needs of demographic groups. We extracted and categorized the pros and cons, operational factors, and strategic considerations for each policy option from the literature review. Experts in health, food, and nutrition were then consulted to prioritize the policy options according to the study’s objectives. The prioritization process utilized four criteria: Public health impact, feasibility, economic impact and budget impact.

Public health impact assesses the potential influence of a policy on risk factors, quality of life, disparities, morbidity, and mortality, scored as low, medium, or high. Feasibility measures the likelihood of successful policy adoption and implementation, also rated as low, medium, or high. Budgetary impact considers the cost of implementation, with ratings ranging from less favorable for higher costs to more favorable for lower costs. Economic effects evaluate the benefits relative to the costs incurred, with possible ratings of less favorable, favorable, or more favorable.

The final step involved prioritizing based on the average scores assigned by the experts to each criterion and policy option. Strategies for implementing the selected policy options were then formulated.

Results

The nutritional support programs identified cater to the general population, specific vulnerable groups, and other targeted initiatives [19]. School feeding programs play a crucial role in combating food insecurity, enhancing nutritional education, and ultimately bolstering health outcomes. Among 192 countries enrolled in the world food program, 117(60.93%) have established school-based feeding programs. Conversely, only eight (4.16%) lack such programs, with Iran being among them. Of the nation’s reporting government-subsidized school meals (n=54), a substantial 87.0% fully subsidize the cost, while the remaining 13.0% offer partial subsidies [23]. Given the critical importance of school feeding programs, they have been incorporated into our research, which will be elaborated upon subsequently.

General distribution

a) India’s PDS: The PDS serves as India’s cornerstone food security system, delivering sustenance to impoverished households. It provides complimentary or discounted rice and pulses, supplemented by reduced-cost oil, salt, and kerosene. Certain regions also include wheat and indigenous grains. The PDS represents a collaborative effort between national and state governments, with the former overseeing procurement, storage, and transportation, and the latter managing distribution. Goods are dispensed through a network of fair-price outlets operated by the state food corporation of India or sanctioned private cooperatives. The PDS differentiates households into priority and non-priority categories, with eligibility criteria set at the state level. Priority households, identified as India’s most impoverished, possess Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) cards or below the poverty line (BPL) cards. Non-priority households are eligible for above the poverty line (APL) cards [5, 24].

b) The SNAP: As the preeminent food aid initiative in the United States, SNAP’s objective is to augment the nutritional intake of low-income families by boosting their buying capacity via electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards or monthly vouchers. These EBT cards are accepted at participating retailers for purchasing qualified food items. SNAP benefit allocations derive from the economic food plan, reflecting the minimal cost of a nutritious diet based on the consumption patterns of various age demographics. This plan encompasses 58 distinct food items, typically constituting around 30% of an average household’s net income [25].

Support for special population groups (pregnant and nursing mothers and children)

a) In Iran, notable ongoing initiatives include:

A nutritional support scheme for malnourished pregnant and nursing mothers, aiming to prevent low birth weight infants [26, 27].

A program for malnourished children aged 6 to 59 months from impoverished families, executed in partnership with the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, featuring monthly growth monitoring and tailored nutritional interventions [28].

A donor-supported initiative aiding malnourished children under five and pregnant and lactating mothers from destitute families not covered by other assistance programs [13].

b) The UK’s welfare food scheme, initially introduced during World War II, provided low-income families with tokens for purchasing milk for children under five. In 2006, the healthy start program supplanted this scheme, offering vouchers for milk, produce, infant formula and vitamins to eligible pregnant women and families with young children, fostering a nutritional safety net and healthier eating habits among the economically disadvantaged [29].

c) In the United States, pivotal nutrition support programs encompass:

The special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children (WIC), established in 1975 to safeguard the well-being of low-income women, infants and children at nutritional risk, offering supplemental food, educational resources and provision of healthcare and social services [30].

The child and adult care food program (CACFP), provides financial compensation to various childcare settings for serving meals and snacks, with funding predominantly directed toward younger children and meal standards set according to age-specific requirements [31].

School support program

The English school free meal program grants complimentary meals to students under 18 from families meeting certain criteria, including low-income and immigration status. In 2014, the program expanded to include all children aged four to eight in public schools. The 2020 nationwide initiative, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, provided eligible families with weekly shopping vouchers. Additionally, a breakfast club was established in 2017, funded by government subsidies and other financial contributions [32].

The national school lunch program (NSLP) in the United States offers daily balanced lunches to students, with a focus on the five food groups and nutritional standards tailored to different age groups. Eligible low-income students receive free or reduced-price meals, while others pay full price. Despite the nation’s wealth, a significant portion of children reside in families struggling to meet basic needs [33].

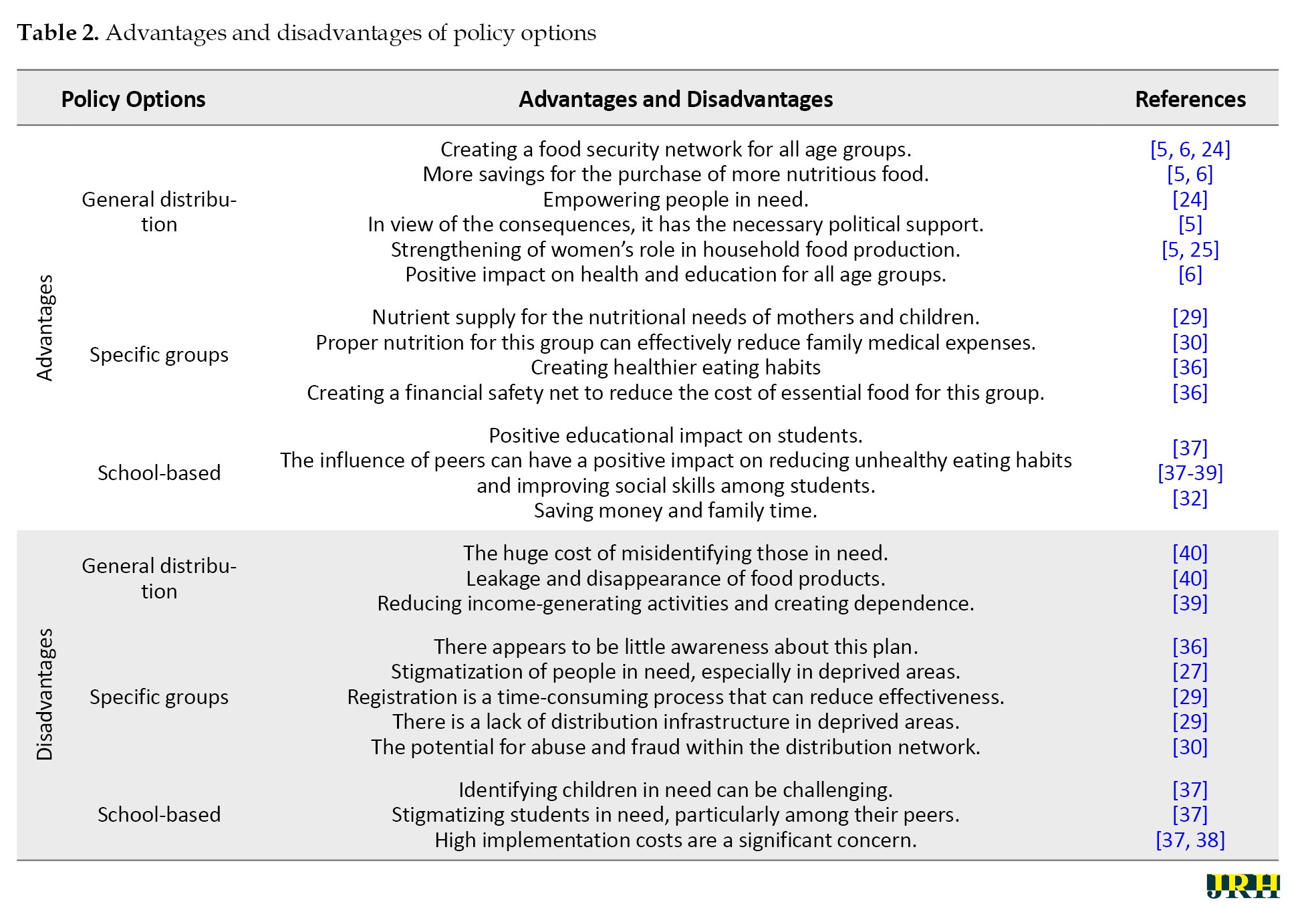

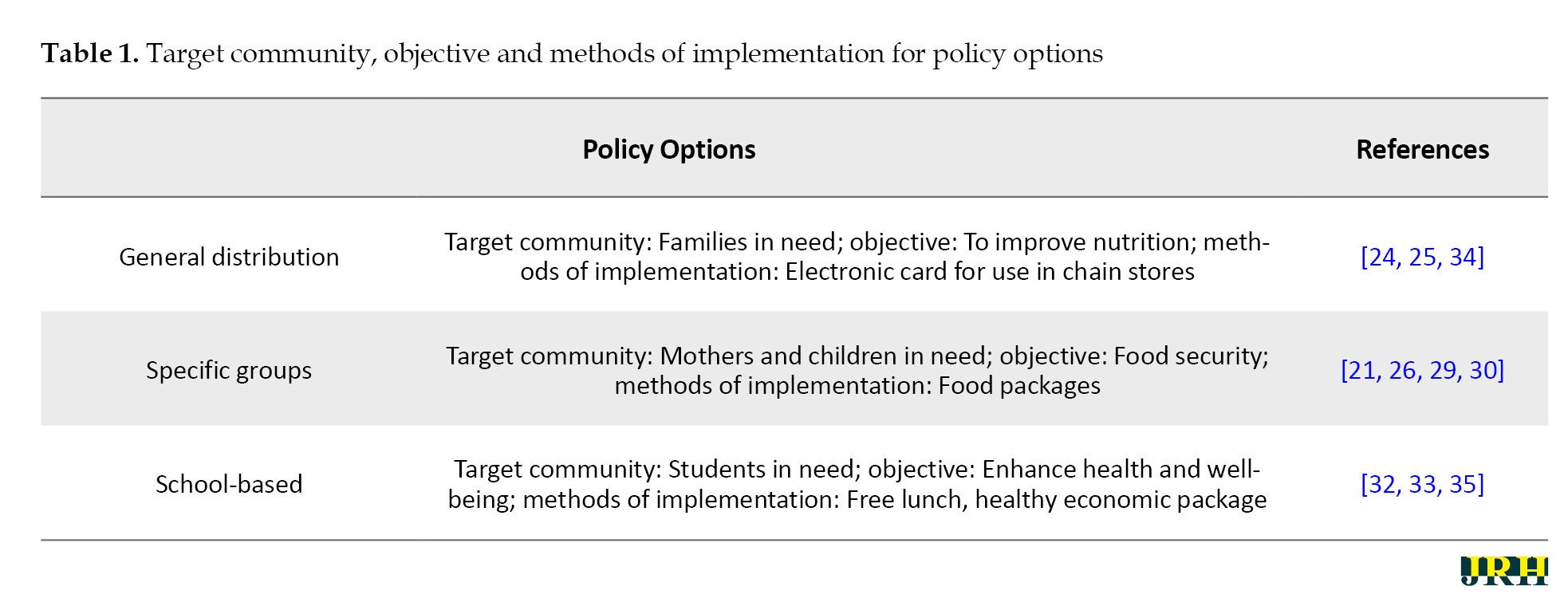

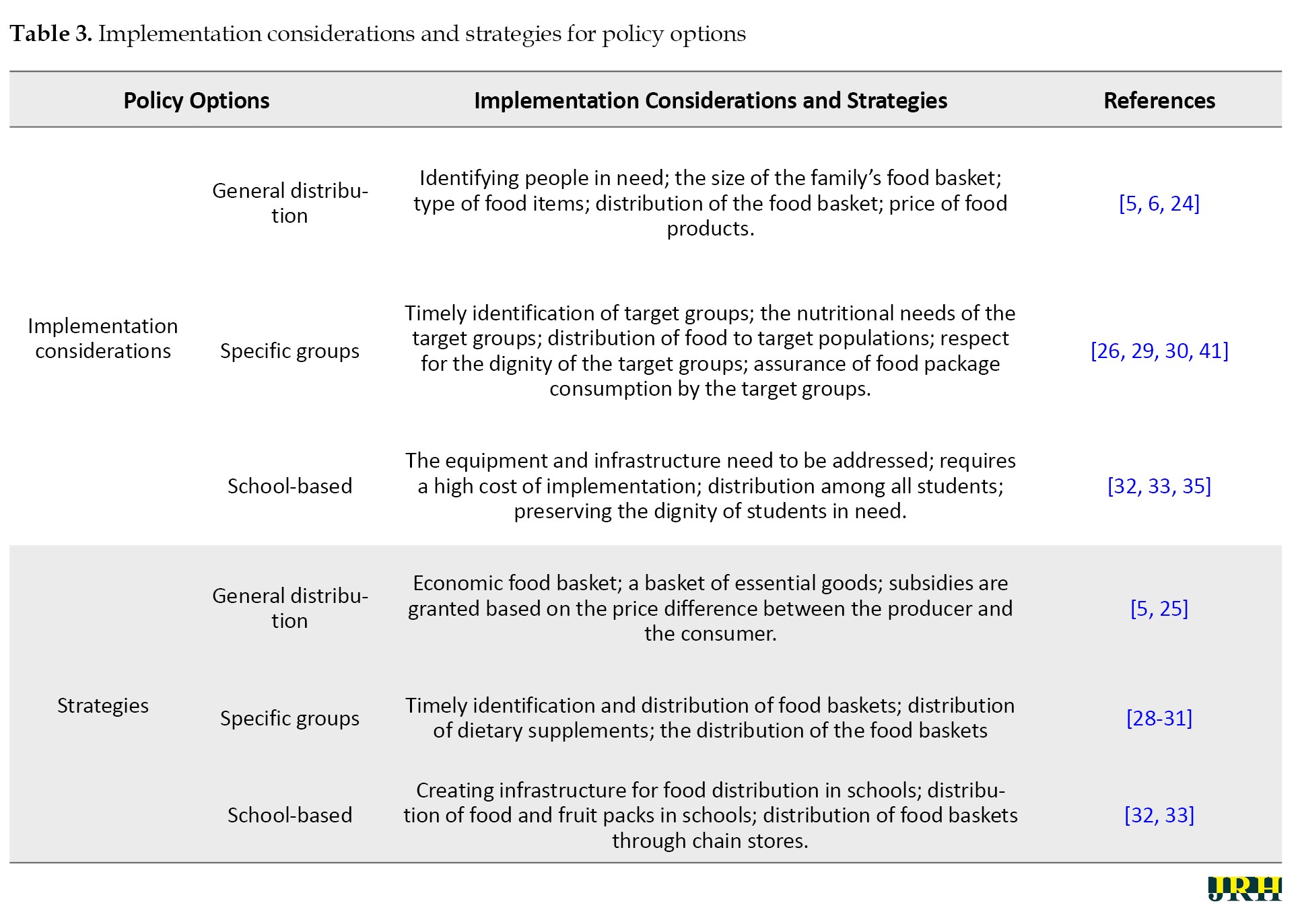

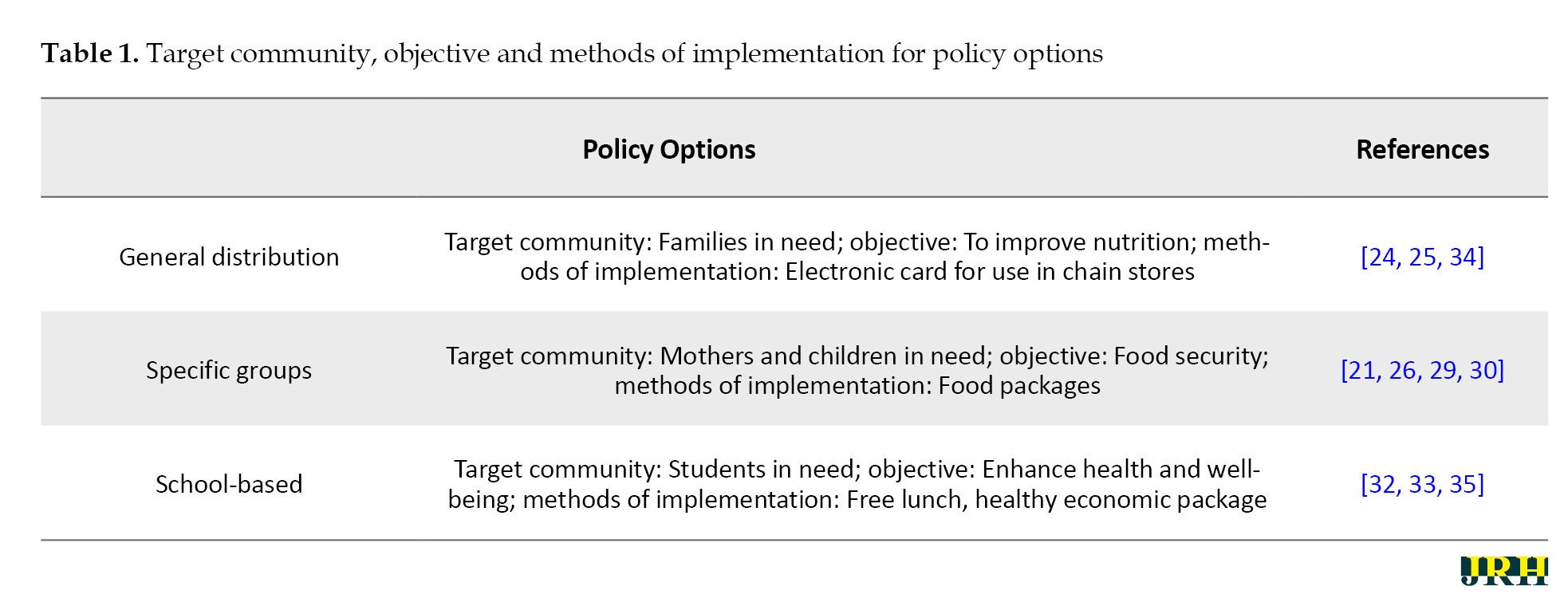

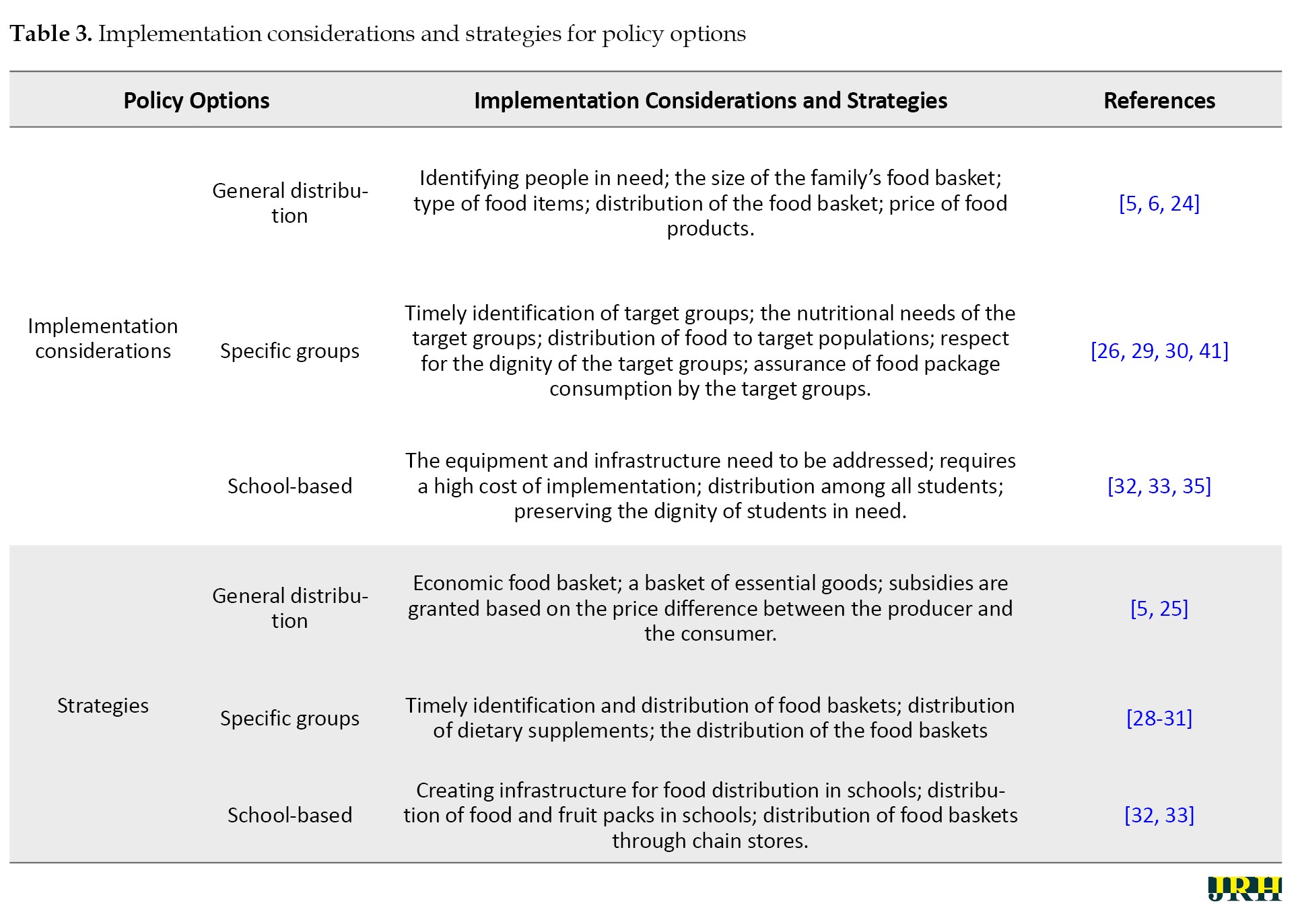

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the characteristics of the aforementioned policy options, while Table 3 details the implementation considerations and strategies for each policy choice, addressing potential issues and outlining necessary approaches for successful deployment.

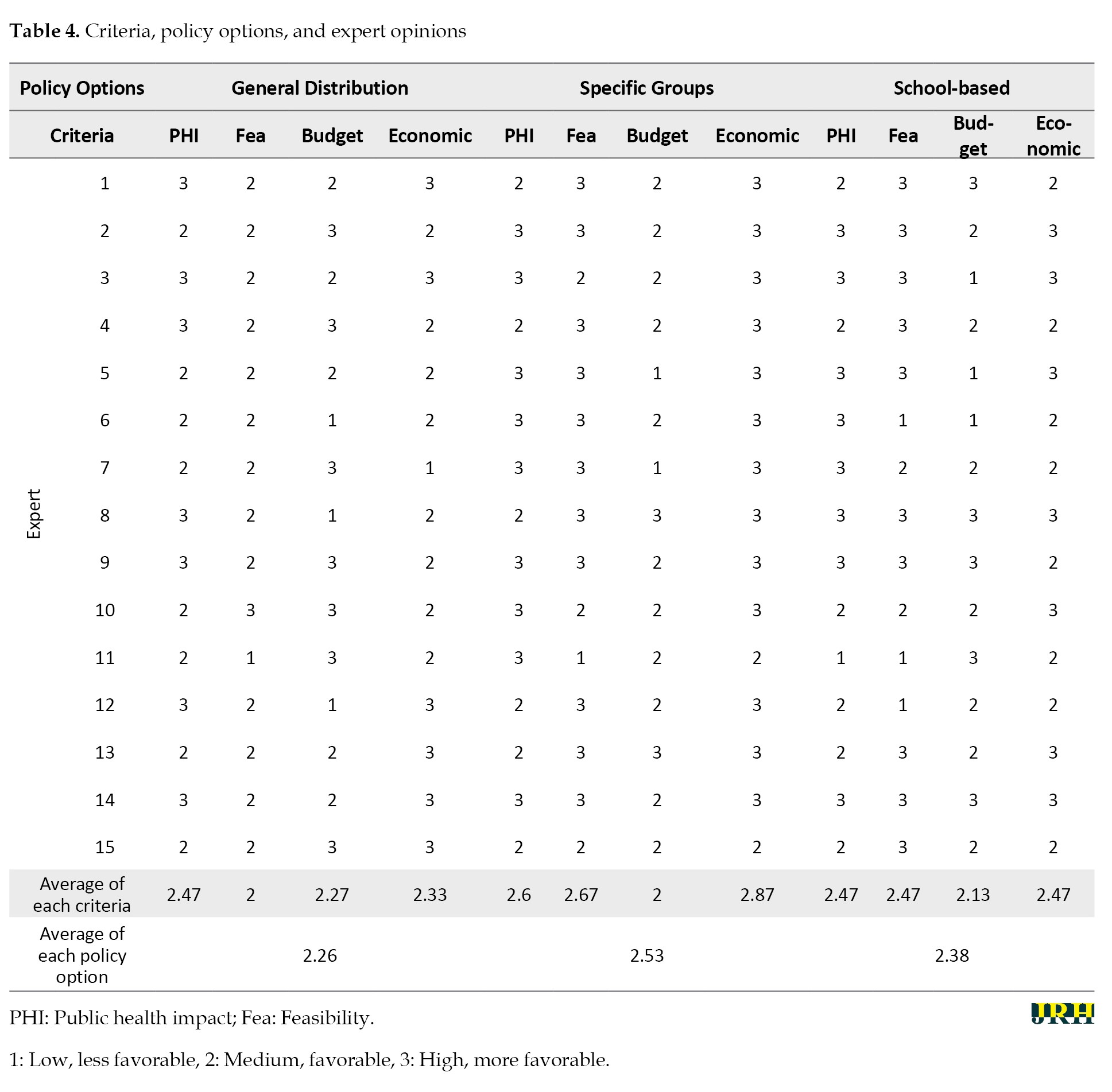

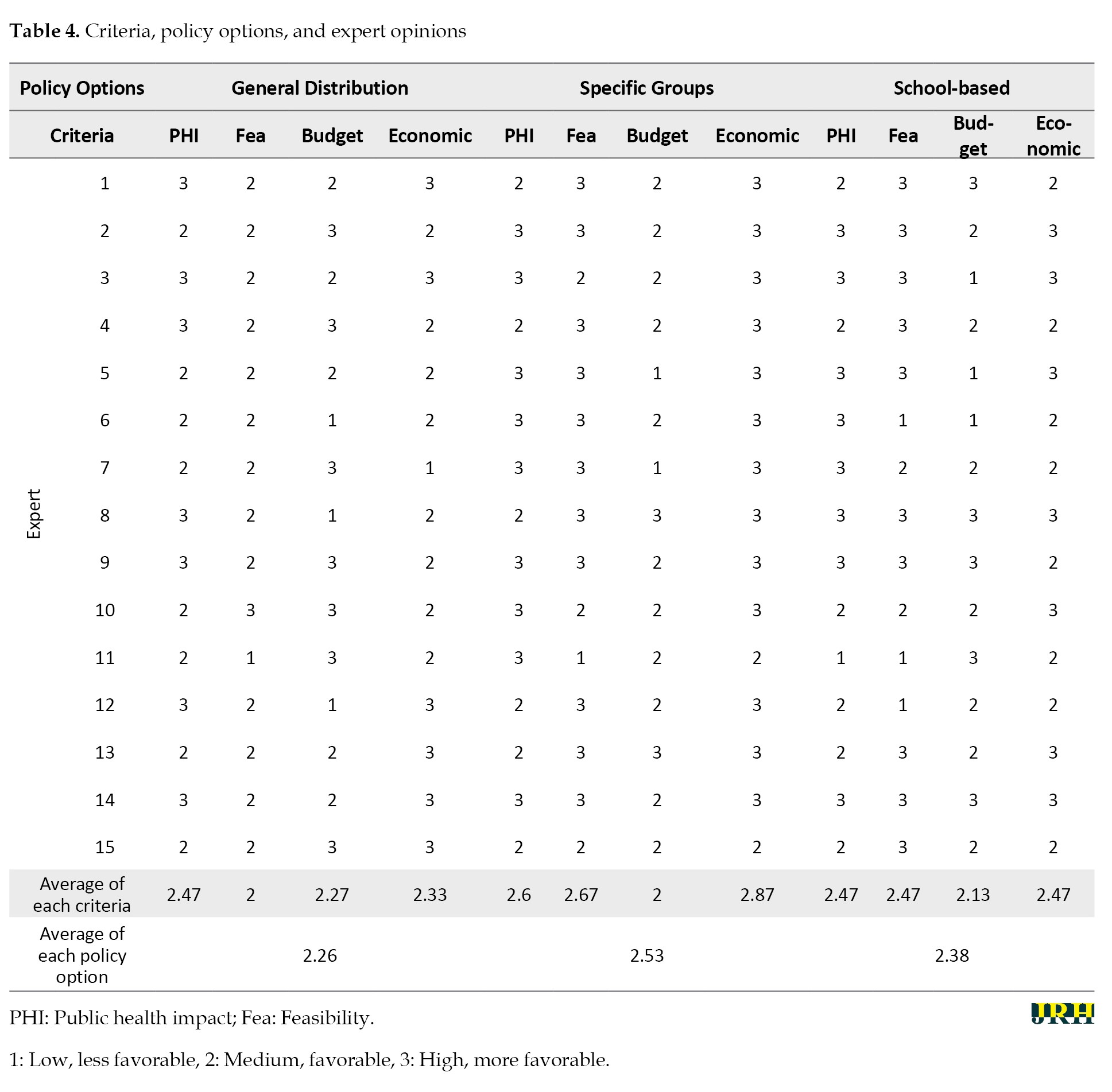

Fifteen experts, comprising eleven men and four women, prioritized policy options based on the data in Tables 1, 2 and 3. The panel included three health policymakers, three food and nutrition policy specialists, three health economists, four healthcare service managers, and one social welfare expert. Their average age was 37.3 years, with an average professional tenure of 9.2 years. Table 4 ranks the policies according to public health impact, feasibility, budgetary considerations, and economic implications.

Specific demographic groups, school-based initiatives, and general distribution emerged as the top three priorities, respectively.

Discussion

Iran’s landscape features a variety of nutritional support programs funded by both government and non-government entities [13, 26, 28]. However, funding shortfalls can delay aid delivery [22]. In-kind subsidies have been proposed to bolster food security sustainably. Drawing from the experiences of India, England, the United States and existing Iranian programs, this study presents three policy options, each with its own set of benefits, drawbacks and implementation factors. Experts weighed these elements against the CDC’s policy analytical framework to establish their priorities.

First priority: Support for specific demographic groups

The prompt provision of essential nutrition is vital for maternal and child health, with delays potentially causing lasting harm and societal costs [29, 30]. Subsidies are thus seen as a reliable means to fulfill the nutritional requirements of vulnerable populations. Special groups received the highest priority, averaging 2.53 in Table 4. The primary strategy involves leveraging the health network for the timely identification of at-risk groups, and distributing food baskets through organizations like the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation. Given resource volatility, it is advisable to source these baskets from subsidized channels to ensure availability. Secondary strategies include dispensing nutritional supplements via pharmacies using shopping cards and monthly food basket provisions through subsidized resources and the capacities of institutions like the State Welfare Organization (Table 3).

Second priority: School-based program

The school-based program, with an average ranking of 2.38 in Table 4, was designated the second priority. Such programs can enhance education and correct poor dietary habits through peer influence, while also freeing parental time (Table 2). Despite its current low priority due to infrastructural deficits, initial steps could involve free lunches in underprivileged areas, with gradual expansion. The government might utilize public and private resources to nourish students, aiming for a healthier future generation. Other strategies include daily healthy food packages for students and distributing economic food baskets through retail chains (Table 3).

Third priority: General distribution of subsidies

General subsidy distribution ranked third, with an average of 2.26 in Table 4. Experts recommend transitioning from cash to in-kind subsidies, covering all demographics with a cost-effective, nutritionally rich food basket (Table 2). This approach leverages chain stores’ capacities, with allocations determined monthly per household head and family size via an electronic system (Table 3). This strategy allows households to allocate funds to other essentials. Additional strategies include defining a basic goods basket for monthly distribution and subsidizing healthy food items based on price differentials, allowing for personal choice within a specified range, and promoting equitable food resource distribution.

Conclusion

The government has delineated a goods basket for in-kind subsidy recipients, distributed through chain stores. Given the requisite infrastructure, public distribution strategies warrant governmental consideration. Experts prioritize nutritional support for vulnerable groups, underscoring the need for timely basket distribution. Sustainable targeted subsidy resources should back strategies for these groups. Timely nutritional support, informed by national experience, can significantly impact health. Long-term plans should focus on developing nutritional infrastructure for students in disadvantaged areas, with an eye on nationwide expansion through sustainable subsidy sources. In the interim, schools could utilize economic food and fruit packages, yielding educational benefits.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hashem Rastegar and Rahim KhodayariZarnaq; Data gathering, data synthesis, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the people who contributed to this research.

Reference

Nutrition is crucial for health, well-being, education, work efficiency, and economic growth. Nearly 795 million people globally suffer from malnutrition, predominantly in developing countries. Recognizing the significance of nutrition, public policies often reallocate resources or provide targeted subsidies to aid vulnerable groups [1-3]. After World War II, consumption subsidies, such as food subsidies and price controls, were introduced to address poverty and food insecurity, a practice that remains in effect [4]. Today, approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide benefit from food subsidies through programs, like Raskin in Indonesia, the public distribution system (PDS) in India, the Tamween program in Egypt and the supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) in the USA, which assist millions in obtaining essential food items [5, 6].

Iran has subsidized petroleum products, basic foodstuffs, medical supplies and utilities since 1980. These subsidies were initially implemented to mitigate the hardships of the eight-year war with Iraq and later to address post-war political and economic challenges. In 2010, the subsidies targeting act was enacted, reforming the payment system and phasing out subsidies for fuel, food, water, electricity, gas and other essentials. The legislation requires that a portion of the savings from subsidy reductions be redistributed to the public in both cash and non-cash forms [7, 8]. The primary aim of this law was to target subsidy payments to benefit the underprivileged segments of society. Following the implementation of this policy, there was a significant increase in household food expenditure, by 823 thousand Rials (approximately $6.36 based on the 2019 exchange rate), indicating that households used the additional cash to enhance their food purchases. However, the initial positive effects of the targeted subsidy reform have diminished over time due to inflation [9]. Since the implementation of the subsidy targeting law a decade ago, it has had a substantial impact on various macroeconomic indicators, such as inflation and income distribution. Sanctions have caused fluctuations in these factors, leading to significant increases in inflation rates between 2017 and 2019 (point-to-point inflation rates of 47.5%, 22% and 49%, respectively). This rise in living costs has led to a 38% increase in the poverty line in 2019 compared to 2018. The combination of high inflation and reduced per capita income due to negative economic growth in 2019 has adversely affected the well-being and living standards of Iranian households, especially those in lower income brackets [10]. Unfortunately, the law has not effectively improved food security for urban and rural households and has been associated with an increase in food insecurity [3, 11]. Lower socioeconomic status and food insecurity within households have become significant factors contributing to growth disorders in children [12]. In 2017, statistics showed that in deprived areas, the rates of underweight and stunted growth in children under five, as well as anemia in pregnant mothers, were more than double the national average. Additionally, deficiencies in vitamin A, zinc and iron were more common among mothers and children in these regions. Insufficient zinc and iron intake during the first 1000 days of life can lead to irreversible complications, such as stunted growth, impaired development, decreased IQ and a weakened immune system [13-15]. To address these challenges, targeted subsidies for food security are essential, given the limited resources available to support vulnerable populations. While physical payments for food may encourage consumption among various groups, cash payments do not necessarily lead to increased food intake [16]. The government has recently revised the subsidy payment method and is developing an electronic infrastructure for non-cash subsidy payments. This research aimed to leverage the experiences of various countries in indirect subsidy disbursement to enhance food security, providing valuable solutions to improve the health of Iranian households and maximize food security for vulnerable groups.

Methods

In our study, we applied the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s policy analytical framework, which serves as a systematic guide for identifying, analyzing, and prioritizing policies that promote health [17]. This framework encompasses several critical steps: Problem identification, policy solution exploration, policy option evaluation, prioritization, and strategy formulation for policy implementation. Under the subsidy targeting law, the government is permitted to allocate up to 50% of the net savings from this legislation towards cash and non-cash subsidies and the establishment of a comprehensive social security system. Social support programs are a key element of this system. It is proposed that, as an initial measure, subsidies should focus on food security, in line with the government’s plan to provide in-kind subsidies. Physical payments for food are expected to enhance consumption among targeted groups, thereby improving food security and public health.

In the second phase, we analyzed nutrition support programs in India, the United States and the United Kingdom to identify and characterize potential policy options. The rationale for selecting these countries includes India’s PDS, the world’s largest food subsidy network serving 800 million people [5, 18], the United States’ implementation of the majority of food subsidy programs [19] and the United Kingdom’s household food security data, which shows a high self-reported rate of food security in 2019–2020 [20]. Additionally, these nations have a long-standing tradition of food subsidies dating back to World War II [21]. In Iran, the nutritional support program for special groups, managed by various organizations, often encounters challenges and inconsistencies in food basket distribution, underscoring the need for targeted subsidies to ensure sustainable food security for those in need [22].

In the third stage, we evaluated policy options by reviewing the experiences of the selected countries and Iran’s current programs. Policy options were developed based on the identified needs of demographic groups. We extracted and categorized the pros and cons, operational factors, and strategic considerations for each policy option from the literature review. Experts in health, food, and nutrition were then consulted to prioritize the policy options according to the study’s objectives. The prioritization process utilized four criteria: Public health impact, feasibility, economic impact and budget impact.

Public health impact assesses the potential influence of a policy on risk factors, quality of life, disparities, morbidity, and mortality, scored as low, medium, or high. Feasibility measures the likelihood of successful policy adoption and implementation, also rated as low, medium, or high. Budgetary impact considers the cost of implementation, with ratings ranging from less favorable for higher costs to more favorable for lower costs. Economic effects evaluate the benefits relative to the costs incurred, with possible ratings of less favorable, favorable, or more favorable.

The final step involved prioritizing based on the average scores assigned by the experts to each criterion and policy option. Strategies for implementing the selected policy options were then formulated.

Results

The nutritional support programs identified cater to the general population, specific vulnerable groups, and other targeted initiatives [19]. School feeding programs play a crucial role in combating food insecurity, enhancing nutritional education, and ultimately bolstering health outcomes. Among 192 countries enrolled in the world food program, 117(60.93%) have established school-based feeding programs. Conversely, only eight (4.16%) lack such programs, with Iran being among them. Of the nation’s reporting government-subsidized school meals (n=54), a substantial 87.0% fully subsidize the cost, while the remaining 13.0% offer partial subsidies [23]. Given the critical importance of school feeding programs, they have been incorporated into our research, which will be elaborated upon subsequently.

General distribution

a) India’s PDS: The PDS serves as India’s cornerstone food security system, delivering sustenance to impoverished households. It provides complimentary or discounted rice and pulses, supplemented by reduced-cost oil, salt, and kerosene. Certain regions also include wheat and indigenous grains. The PDS represents a collaborative effort between national and state governments, with the former overseeing procurement, storage, and transportation, and the latter managing distribution. Goods are dispensed through a network of fair-price outlets operated by the state food corporation of India or sanctioned private cooperatives. The PDS differentiates households into priority and non-priority categories, with eligibility criteria set at the state level. Priority households, identified as India’s most impoverished, possess Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) cards or below the poverty line (BPL) cards. Non-priority households are eligible for above the poverty line (APL) cards [5, 24].

b) The SNAP: As the preeminent food aid initiative in the United States, SNAP’s objective is to augment the nutritional intake of low-income families by boosting their buying capacity via electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards or monthly vouchers. These EBT cards are accepted at participating retailers for purchasing qualified food items. SNAP benefit allocations derive from the economic food plan, reflecting the minimal cost of a nutritious diet based on the consumption patterns of various age demographics. This plan encompasses 58 distinct food items, typically constituting around 30% of an average household’s net income [25].

Support for special population groups (pregnant and nursing mothers and children)

a) In Iran, notable ongoing initiatives include:

A nutritional support scheme for malnourished pregnant and nursing mothers, aiming to prevent low birth weight infants [26, 27].

A program for malnourished children aged 6 to 59 months from impoverished families, executed in partnership with the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, featuring monthly growth monitoring and tailored nutritional interventions [28].

A donor-supported initiative aiding malnourished children under five and pregnant and lactating mothers from destitute families not covered by other assistance programs [13].

b) The UK’s welfare food scheme, initially introduced during World War II, provided low-income families with tokens for purchasing milk for children under five. In 2006, the healthy start program supplanted this scheme, offering vouchers for milk, produce, infant formula and vitamins to eligible pregnant women and families with young children, fostering a nutritional safety net and healthier eating habits among the economically disadvantaged [29].

c) In the United States, pivotal nutrition support programs encompass:

The special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children (WIC), established in 1975 to safeguard the well-being of low-income women, infants and children at nutritional risk, offering supplemental food, educational resources and provision of healthcare and social services [30].

The child and adult care food program (CACFP), provides financial compensation to various childcare settings for serving meals and snacks, with funding predominantly directed toward younger children and meal standards set according to age-specific requirements [31].

School support program

The English school free meal program grants complimentary meals to students under 18 from families meeting certain criteria, including low-income and immigration status. In 2014, the program expanded to include all children aged four to eight in public schools. The 2020 nationwide initiative, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, provided eligible families with weekly shopping vouchers. Additionally, a breakfast club was established in 2017, funded by government subsidies and other financial contributions [32].

The national school lunch program (NSLP) in the United States offers daily balanced lunches to students, with a focus on the five food groups and nutritional standards tailored to different age groups. Eligible low-income students receive free or reduced-price meals, while others pay full price. Despite the nation’s wealth, a significant portion of children reside in families struggling to meet basic needs [33].

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the characteristics of the aforementioned policy options, while Table 3 details the implementation considerations and strategies for each policy choice, addressing potential issues and outlining necessary approaches for successful deployment.

Fifteen experts, comprising eleven men and four women, prioritized policy options based on the data in Tables 1, 2 and 3. The panel included three health policymakers, three food and nutrition policy specialists, three health economists, four healthcare service managers, and one social welfare expert. Their average age was 37.3 years, with an average professional tenure of 9.2 years. Table 4 ranks the policies according to public health impact, feasibility, budgetary considerations, and economic implications.

Specific demographic groups, school-based initiatives, and general distribution emerged as the top three priorities, respectively.

Discussion

Iran’s landscape features a variety of nutritional support programs funded by both government and non-government entities [13, 26, 28]. However, funding shortfalls can delay aid delivery [22]. In-kind subsidies have been proposed to bolster food security sustainably. Drawing from the experiences of India, England, the United States and existing Iranian programs, this study presents three policy options, each with its own set of benefits, drawbacks and implementation factors. Experts weighed these elements against the CDC’s policy analytical framework to establish their priorities.

First priority: Support for specific demographic groups

The prompt provision of essential nutrition is vital for maternal and child health, with delays potentially causing lasting harm and societal costs [29, 30]. Subsidies are thus seen as a reliable means to fulfill the nutritional requirements of vulnerable populations. Special groups received the highest priority, averaging 2.53 in Table 4. The primary strategy involves leveraging the health network for the timely identification of at-risk groups, and distributing food baskets through organizations like the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation. Given resource volatility, it is advisable to source these baskets from subsidized channels to ensure availability. Secondary strategies include dispensing nutritional supplements via pharmacies using shopping cards and monthly food basket provisions through subsidized resources and the capacities of institutions like the State Welfare Organization (Table 3).

Second priority: School-based program

The school-based program, with an average ranking of 2.38 in Table 4, was designated the second priority. Such programs can enhance education and correct poor dietary habits through peer influence, while also freeing parental time (Table 2). Despite its current low priority due to infrastructural deficits, initial steps could involve free lunches in underprivileged areas, with gradual expansion. The government might utilize public and private resources to nourish students, aiming for a healthier future generation. Other strategies include daily healthy food packages for students and distributing economic food baskets through retail chains (Table 3).

Third priority: General distribution of subsidies

General subsidy distribution ranked third, with an average of 2.26 in Table 4. Experts recommend transitioning from cash to in-kind subsidies, covering all demographics with a cost-effective, nutritionally rich food basket (Table 2). This approach leverages chain stores’ capacities, with allocations determined monthly per household head and family size via an electronic system (Table 3). This strategy allows households to allocate funds to other essentials. Additional strategies include defining a basic goods basket for monthly distribution and subsidizing healthy food items based on price differentials, allowing for personal choice within a specified range, and promoting equitable food resource distribution.

Conclusion

The government has delineated a goods basket for in-kind subsidy recipients, distributed through chain stores. Given the requisite infrastructure, public distribution strategies warrant governmental consideration. Experts prioritize nutritional support for vulnerable groups, underscoring the need for timely basket distribution. Sustainable targeted subsidy resources should back strategies for these groups. Timely nutritional support, informed by national experience, can significantly impact health. Long-term plans should focus on developing nutritional infrastructure for students in disadvantaged areas, with an eye on nationwide expansion through sustainable subsidy sources. In the interim, schools could utilize economic food and fruit packages, yielding educational benefits.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hashem Rastegar and Rahim KhodayariZarnaq; Data gathering, data synthesis, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the people who contributed to this research.

Reference

- Ahmadi A, Mojaradi GR, Badsar M. [Study of socio-economic impact of targeted subsidies law on rural households’ quality of life in Urmia township (Persian)]. Agricultural Extension and Education Research. 2017; 9(3):43-54. [Link]

- Fan Y, Zhang, G. [The welfare effect of a consumer subsidy with price ceilings: The case of Chinese cell phones. The RAND Journal of Economics. 2022; 53(2):429-49. [DOI:10.1111/1756-2171.12413]

- Hosseini SS, Charvadeh MP, Salami H, Flora C. The impact of the targeted subsidies policy on household food security in urban areas in Iran. Cities. 2017; 63:110-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.cities.2017.01.003]

- Zhong T, Crush J, Song Y, Si Z, Scott S, Peng Y. Urban food insecurity and the impact of China’s affordable food shop (AFS) program: A case study of Nanjing city. Applied Geography. 2023; 154:102924. [DOI:10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.102924]

- Shrinivas A, Baylis K, Crost B, Pingali P. Do staple food subsidies improve nutrition. [Unpublished]. [Link]

- Furman J, Munoz C, Black S. Long-Term benefits of the supplemental nutrition assistance program. Washington: Executive Office of the President, Council of Economic Advisors; 2015. [Link]

- Sadrabadi FI, Samsami H. [The effect ofthe second stage of subsidieson income distributionin the economy of Iran (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Quantitative Economics 2016; 13(1):31-47. [DOI:10.22055/jqe.2016.12325]

- Nikou SN. The subsidies conundrum [Internet]. 2010 [Updatyed 2010 September 8]. Available from: [Link]

- Saeediankia A, Emamgholipour S, Pouraram H, Mousavi A, Majdzadeh R. Impact of targeted subsidies reform on household nutrition: Lessons learned from Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2023; 52(7):1504-13. [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v52i7.13253] [PMID]

- Shahidi Z, Kaviani Z. [Poverty monitoring in 2019 (Persian)]. Tehran: Bureau of Social Welfare Studies, Ministry of Cooperation, Labor and Social Welfare; 2020. [Link]

- Hamzehi M, Anabestani A, Javan J. Impact of targeted subsidies implementation on poverty and instability of rural household economy in Iran (case study: Villages of Neishabour county). Regional Planning. 2022; 12(45):83-108. [DOI:10.30495/jzpm.2022.4284]

- Gholampour T, Noroozi M, Zavoshy R, Mohammadpoorasl A, Ezzeddin N. Relationship between household food insecurity and growth disorders in children aged 3 to 6 in Qazvin City, Iran. Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition. 2020; 23(5):447-56. [DOI:10.5223/pghn.2020.23.5.447] [PMID]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education. [Nutritional support for children under five years old and pregnant and lactating mothers Malnourished needy families with the participation of donors (Persian)]. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2019. [Link]

- Taghizadeh S, Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Farhangi MA. Childhood obesity prevention policies in Iran: A policy analysis of agenda-setting using Kingdon's multiple streams. BMC Pediatrics. 2021; 21(1):250. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-021-02731-y] [PMID]

- Taghizadeh S, Farhangi MA, Khodayari-Zarnaq R. Stakeholders perspectives of barriers and facilitators of childhood obesity prevention policies in Iran: A delphi method study. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):2260. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-12282-7] [PMID]

- Saeediankia A, Majdzadeh R, Haghighian-Roudsari A, Pouraram H. The effects of subsidies on foods in Iran: A narrative review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 2022; 6:1053851. [DOI:10.3389/fsufs.2022.1053851]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s policy analytical framework. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Link]

- Ginn W, Pourroy M. The contribution of food subsidy policy to monetary policy in India. Economic Modelling. 2022; 113:105904. [DOI:10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105904]

- Mansilla C, Herrera CA, von Uexkull E. Food subsidies to promote healthy eating and reduce food prices: A rapid literature review. Washington: World Bank Group; 2023. [Link]

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. UK Food Security Report 2021. UK: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; 2021. [Link]

- Black AP, Brimblecombe J, Eyles H, Morris P, Vally H, O Dea K. Food subsidy programs and the health and nutritional status of disadvantaged families in high income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:1099. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1099] [PMID]

- Ghodsi D, Rashidian A, Omidvar N, Eini-Zinab H, Raghfar H, Ebrahimi M. Process evaluation of a national, community-based, food supplementary programme for improving the nutritional status of children in Iran. Public Health Nutrition. 2018; 21(15):2811-8. [DOI:10.1017/S1368980018001696] [PMID]

- Cupertino A, Ginani V, Cupertino AP, Botelho RBA. School feeding programs: What happens globally? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2265. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19042265] [PMID]

- Cunningham SA, Shaikh NI, Datar A, Chernishkin AE, Patil SS. Food subsidies, nutrition transition, and dietary patterns in a remote Indian district. Global Food Security. 2021; 29:100506. [DOI:10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100506]

- National Academic. Supplemental nutrition assistance program: Examining the evidence to define benefit adequacy. Washington: National Academic; 2013. [DOI:10.17226/13485]

- Asghari A, Pourali F, Ismaili A, Abbasalti Z. Nutritional support program for pregnant and lactating mothers in need. Behvarz. 2014; 25(90):74-5. [DOI:10.22038/behv.2014.15167]

- Torabi P, Nobakht Hghighi F, Minaei M, Zarei M, Sadeghi Ghotb Abadi F, Salehi Mazandarani F, et al. [The educational content of nutrition in the field of behvarz in the associate degree (Persian)]. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2019. [Link]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education. [Implementation instructions for the nutritional support program for malnourished children from 6 to 59 months of needy families (Persian)]. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2021. [Link]

- Crawley H, Dodds R. The UK Healthy Start scheme. What happened? What next? London: First Steps Nutrition Trust; 2018. [Link]

- Oliveira VJ, Frazão E. The WIC program: Background, trends, and economic issues. Collingdale: DIANE Publishing; 2009. [Link]

- Heflin C, Arteaga I, Gable S. The child and adult care food program and food insecurity. Social Service Review. 2015; 89(1):77-98. [DOI:10.1086/679760]

- Long R, Bolton P. School meals and nutritional standards (England) [Internet]. 2021 [Updated 2024 October 8]. Available from: [Link]

- Izumi BT, Bersamin A, Shanks CB, Grether-Sweeney G, Murimi M. The US national school lunch program: A brief overview. The Japanese Journal of Nutrition Dietetics. 2018; 76:S126-32. [DOI:10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.76.S126]

- Kaushal N, Muchomba FM. How consumer price subsidies affect nutrition. World Development. 2015; 74:25-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.006]

- Department for Work and Pensions. Free school meal entitlement and child poverty in England. London: Department of Work and Pensions; 2013. [Link]

- Szpakowicz D. The healthy start scheme: An Evidence Review. Edinburgh: Scottish Government Children and Families Analytical Services; 2016. [Link]

- Ralston KL, Newman C, Clauson AL, Guthrie JF, Buzby JC. The national school lunch program background, trends, and issues [Internet]. 2008 [Updated 2008 July 18]. Available From: [Link]

- Kitchen S, Tanner E, Brown V, et al. Evaluation of the free school meals pilot. London: Department for Education; 2013. [Link]

- Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Sadegh Tabrizi J, Jalilian H, Khezmeh H, Jafari H, Sajadi MK. [Assessment of schools health activities and programs in the field of healthy diet and nutrition in Tabriz city in 2017 (Persian)]. Management Strategies in Health System 2017; 2(3):181-92. [Link]

- Paul S. Evaluation study of targeted public distribution system. New Delhi: National Council of Applied Economic; 2015.

- Heflin CM, Siefert K, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and women's mental health: Findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Social Science & Medicine. 2005; 61(9):1971-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.014] [PMID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

● Disease Control

Received: 2023/08/22 | Accepted: 2024/06/5 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2023/08/22 | Accepted: 2024/06/5 | Published: 2025/03/2

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |