Volume 15, Issue 1 (Jan & Feb 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(1): 105-116 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ARUMS.REC.1402.004

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

NeJhaddadgar N, Darabi F, Ezati F. Factors Affecting Inducted Abortion: A Scoping Review. J Research Health 2025; 15 (1) :105-116

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2501-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2501-en.html

1- Department of Health Promotion and Education, Faculty of Public Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Department of Public Health, Asadabad School of Medical Sciences, Asadabad, Iran.

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran. ,f.ezzati1378@gmail.com

2- Department of Public Health, Asadabad School of Medical Sciences, Asadabad, Iran.

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran. ,

Keywords: Induced abortion, Factors induced abortion

Full-Text [PDF 898 kb]

(917 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3289 Views)

Full-Text: (1533 Views)

Introduction

The loss and termination of pregnancy for any reason before the 22nd week of pregnancy is referred to as abortion [1]. As one of the safest gynecological surgical procedures, legal abortion is less dangerous than natural childbirth. However, unsafe abortion is one of the biggest neglected health problems in developing countries, being a major problem in women’s lives during their reproductive years. This type of abortion occurs outside legal systems and in environments with minimal medical standards, often performed by individuals who lack the necessary skills [2]. Accurate information regarding the number and physical, mental, psychological, social, and economic consequences of illegal abortion cannot be obtained in countries where abortion is not legal. Hospitals are not visited for secret complete abortions. Therefore, hospital data does not only represent the tip of the iceberg. Since abortion is seen as a reprehensible act, its guardian is always absent from healthcare programs. However, its complications are undeniable [3]. Some cases of hospitalization among young women in developing countries are rooted in the consequences of unsafe abortions. An estimated 22 million unsafe abortions are reported to occur annually worldwide, of which 98% take place in developing countries. Moreover, 5 million women suffer from the complications of unsafe abortion, including bleeding, infection, and damage to the reproductive system and abdominal organs [4].

Every year, approximately 25 million unsafe abortions occur worldwide, of which, 97% are reported in developing countries, with half of them occurring in Asia. Unsafe abortion plays an important role in maternal morbidity, disability, and mortality, largely due to post-abortion sepsis, hemorrhage, genital trauma, infection, and infertility. Recent estimates suggest that about 13% of global maternal deaths are attributed to unsafe abortion. Also, approximately seven million women undergo treatment due to complications resulting from unsafe abortion, and about five million women suffer disability as a result of such complications [5].

In Iran, abortion is allowed only if the mother’s life is in danger or the fetus is suffering from certain diseases; thus, induction abortion is performed. Apart from these circumstances, all other induced abortions are considered intentional abortions.

In recent years, various studies have been conducted in different countries about intentional abortion. In Jamaica, although abortion is unforgivable, there are certain customs for its acceptance in society. In southern Cameroon, while abortion is stigmatized, its social and moral consequences are considered less severe than those of an unplanned pregnancy, and despite this stigma, abortions are still performed in southern Cameroon [6]. In Thailand, abortion is illegal, except in cases where it is necessary for the mother’s health or if sexual assault is the cause of pregnancy; several methods are used for abortion in these cases. In Kenya, induced abortion is relatively common, especially among women, and young single urban women, who have limited access to pregnancy control facilities. In South Asia, Nepal has become a pioneer in the legalization, implementation, and scaling up of safe abortion services [7].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) report, most European countries allow legal abortion in all circumstances, except for Ireland and Andorra, which only allow abortion in the cases of saving the life of the mother, and England, which allows abortion only in cases of saving the mother’s life, at the mother’s request, or in instances of sexual assault. Malta is the only European country that does not allow abortion in any context [8].

Nearly 530,000 intentional abortions take place in Iran every year. Intended or criminal abortions constitute nearly one-third of all abortions, which is a significant proportion. According to official statistics, the abortion rate is about 8% in Ardabil Province. These abortions are identified by the health system, and there are no statistics on criminal abortions. Therefore, a better approach is to take measures that reduce the number of illegal abortions. The first way to do this is to reduce the number of unintended pregnancies. The number of illegal abortions can be significantly reduced if investments are made in this area. Some effective measures are comprehensive sexual health education, which provides accurate medical information about contraception, insurance coverage, access to contraceptives for those in need, and programs that address domestic violence and sexual abuse [9].

The key causes of abortion must be identified to reduce maternal mortality and unsafe abortions. Accordingly, this study was conducted to investigate the factors affecting induced and criminal abortions so that effective solutions can be provided based on the results for policy-making. Among the methods of review studies, the scoping review is an appropriate method to answer the questions “what” and “why” in a specific subject area. The scoping review method can be used when the main subject of the study and its documents are broad and complex or have not been extensively and comprehensively examined [10].

A scoping review is used for reasons, such as identifying the types of evidence of the subject under investigation, expressing the generality of the subject, identifying its key concepts, such as definitions and conceptual models, drawing a map of the relevant literature, identifying the research methods used in the field under investigation, examining the nature and scope of studies and research evidence produced, summarizing and publishing research findings, identifying and analyzing research gaps in the relevant literature, and determining the necessity of conducting a systematic review [10, 11]. Arksey and O’Malley’s six-stage methodological framework was used in this scoping review. These stages are:

1. Identifying the research questions

2. Identifying relevant studies using reliable databases and reviewing gray texts, theses, review articles, and references of studies in the research area

3. Selecting related studies from primary studies

4. Mapping out the data ::as char::ts and tables

5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

6. Including expert consultation

Unlike a systematic review that seeks to answer a specific question [12, 13], a scoping review seeks to answer several questions [10]. The questions of this study were as follows:

1. What factors cause women to have an abortion?

2. What are the most common factors?

Methods

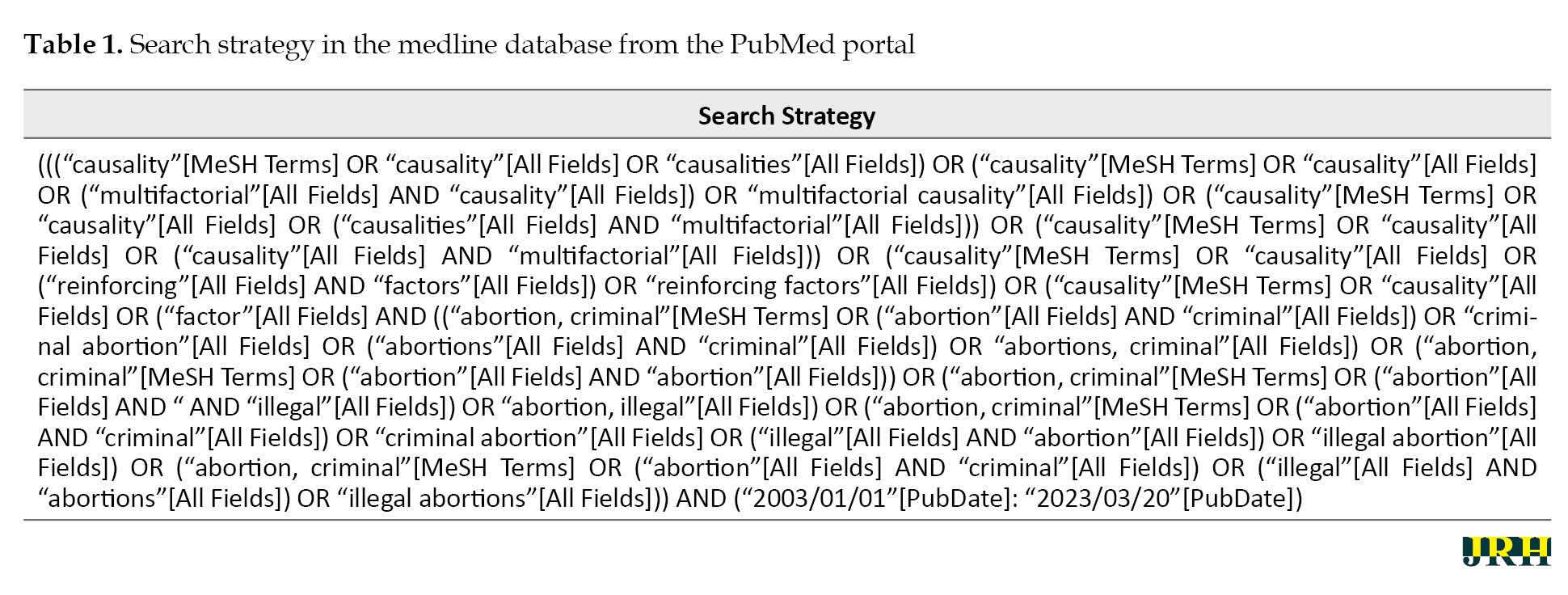

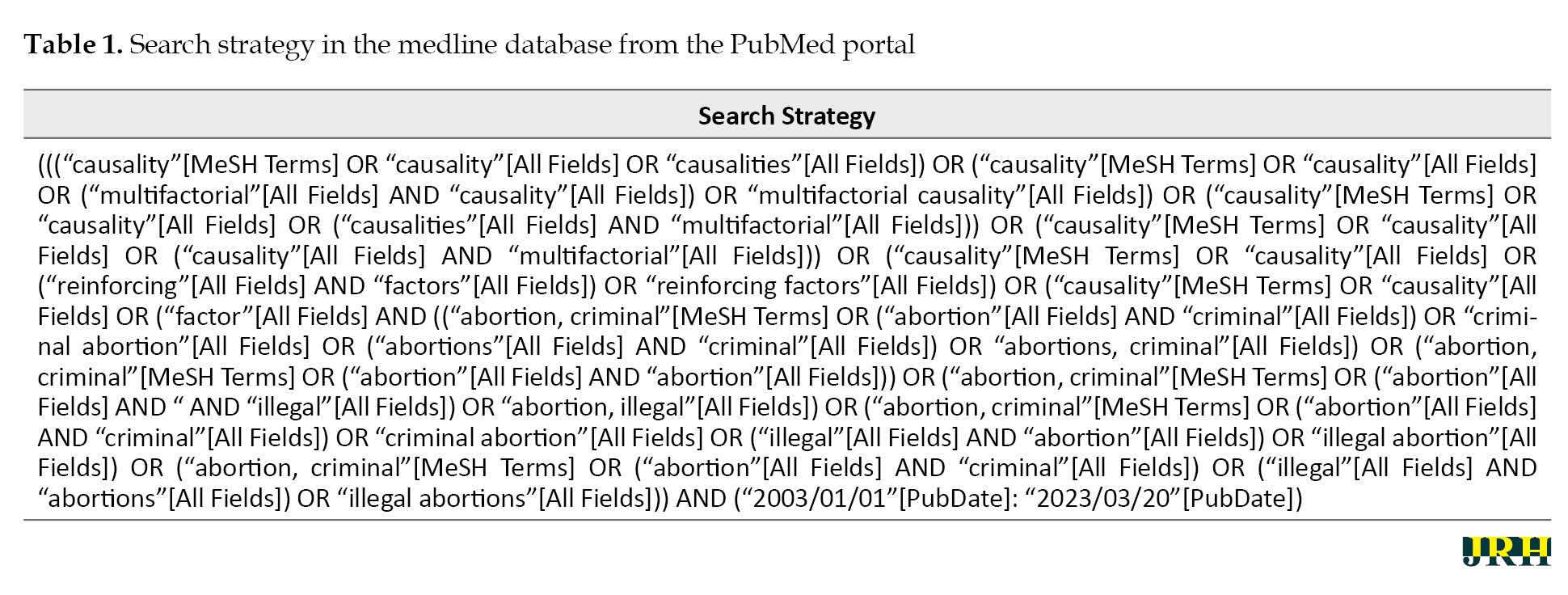

This scoping review was conducted at Ardabil University of Medical Sciences in 2023. International databases, such as Springer, PubMed, Web of Science, Emerald, ScienceDirect, and Scopus, as well as national databases, such as Magiran and SID, and search engines, such as Google Scholar, were searched to find relevant studies. The keywords used for the search included MeSH terms, and the common keywords concerning the studied topic included as follows:

Causalities, multifactorial causality, multifactorial, reinforcing, causality, reinforcing factors, factor, causation, causations, enabling factors, enabling factor, factor, enabling factor, abortions, criminal, criminal abortion, abortion, illegal, illegal abortion, abortions (Table 1).

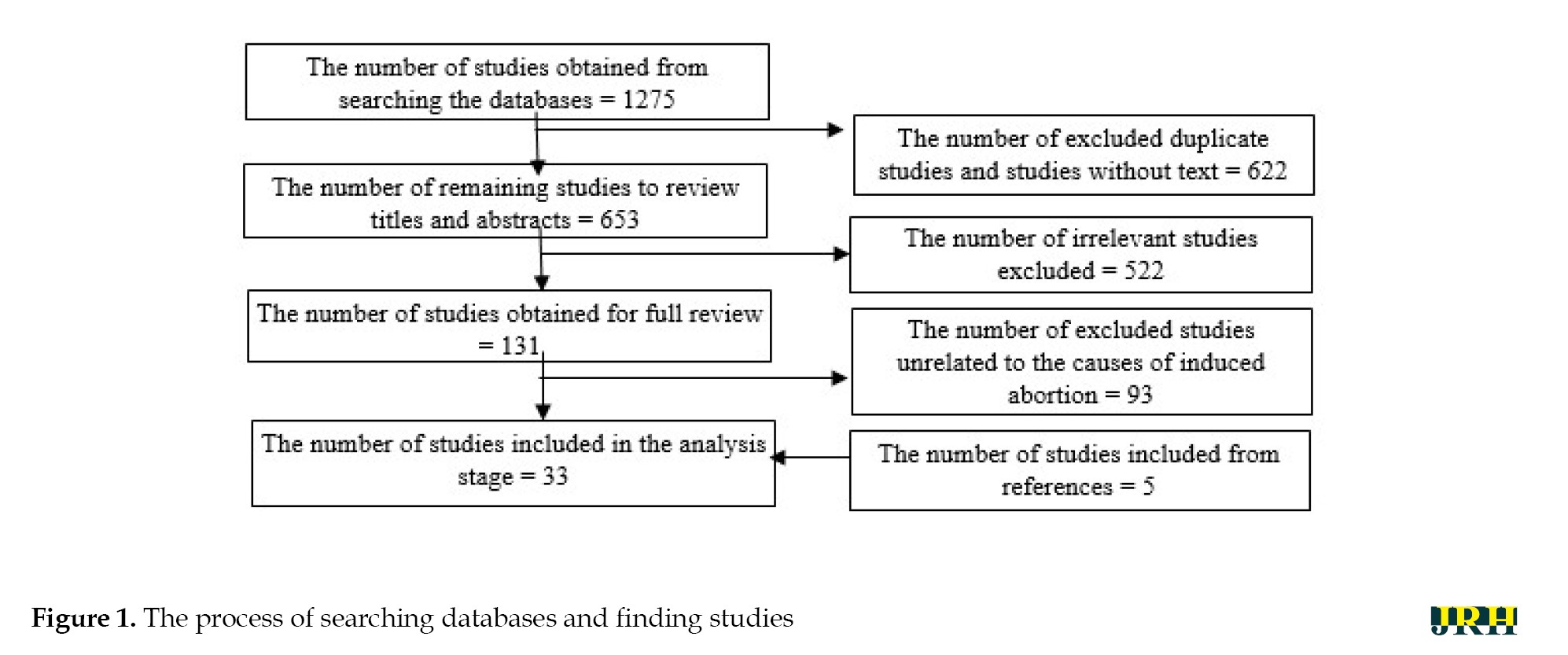

The inclusion criteria were all studies on factors affecting induced abortion from January 1, 2003, to March 20, 2023. The exclusion criteria were studies published in languages other than Persian and English, studies published after the end of March 20, 2023, and scientific references without full text. A total of 1275 studies were found in the initial search. After excluding duplicate studies and studies without full text, 653 studies were obtained for the review of titles and abstracts, of which 522 were excluded due to being unrelated. At this stage, 131 studies on factors affecting induced abortion were retained. After a thorough review of the studies, 93 were excluded due to irrelevance and low quality. After reviewing the references, five studies were added to the final review process. Finally, 33 review studies on factors affecting induced abortion were assessed (Figure 1). The data extraction form included the authors’ profiles, journal name, year of publication, purpose of the study, year of the study, type of study, data collection method, and factors affecting induced abortion. The data were analyzed using a qualitative approach and content analysis and were coded using MAXQDA software, version 20. The themes and sub-themes of each study were then extracted to define the relationship between the themes and identify the main concepts and models. The studies were evaluated using a valid checklist for the evaluation of review and research studies. The minimum and maximum scores that could be obtained were 1 and 15, respectively, and the minimum acceptable score was 10 [14]. A Kappa coefficient of 78% was obtained (P=0.00).

Results

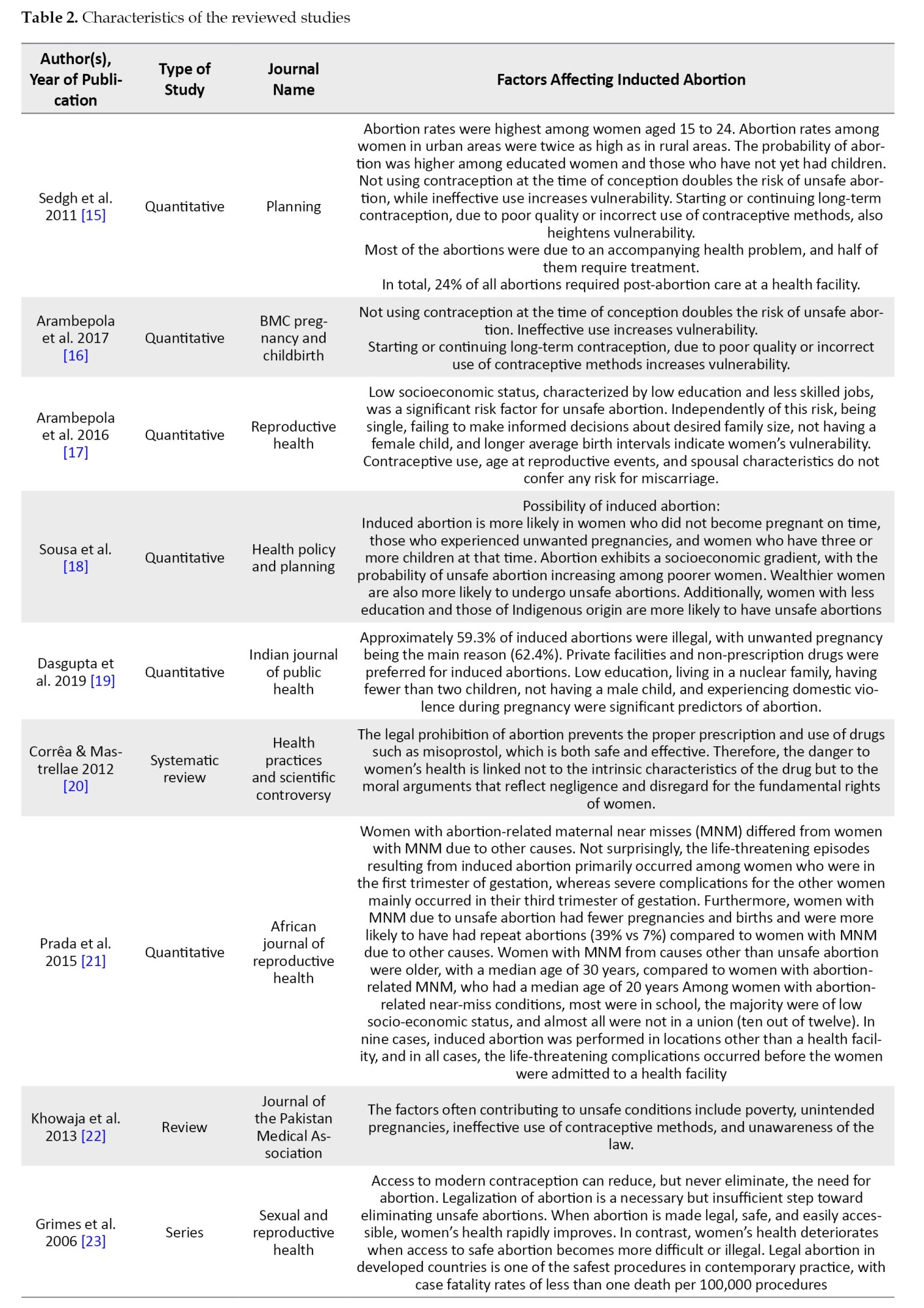

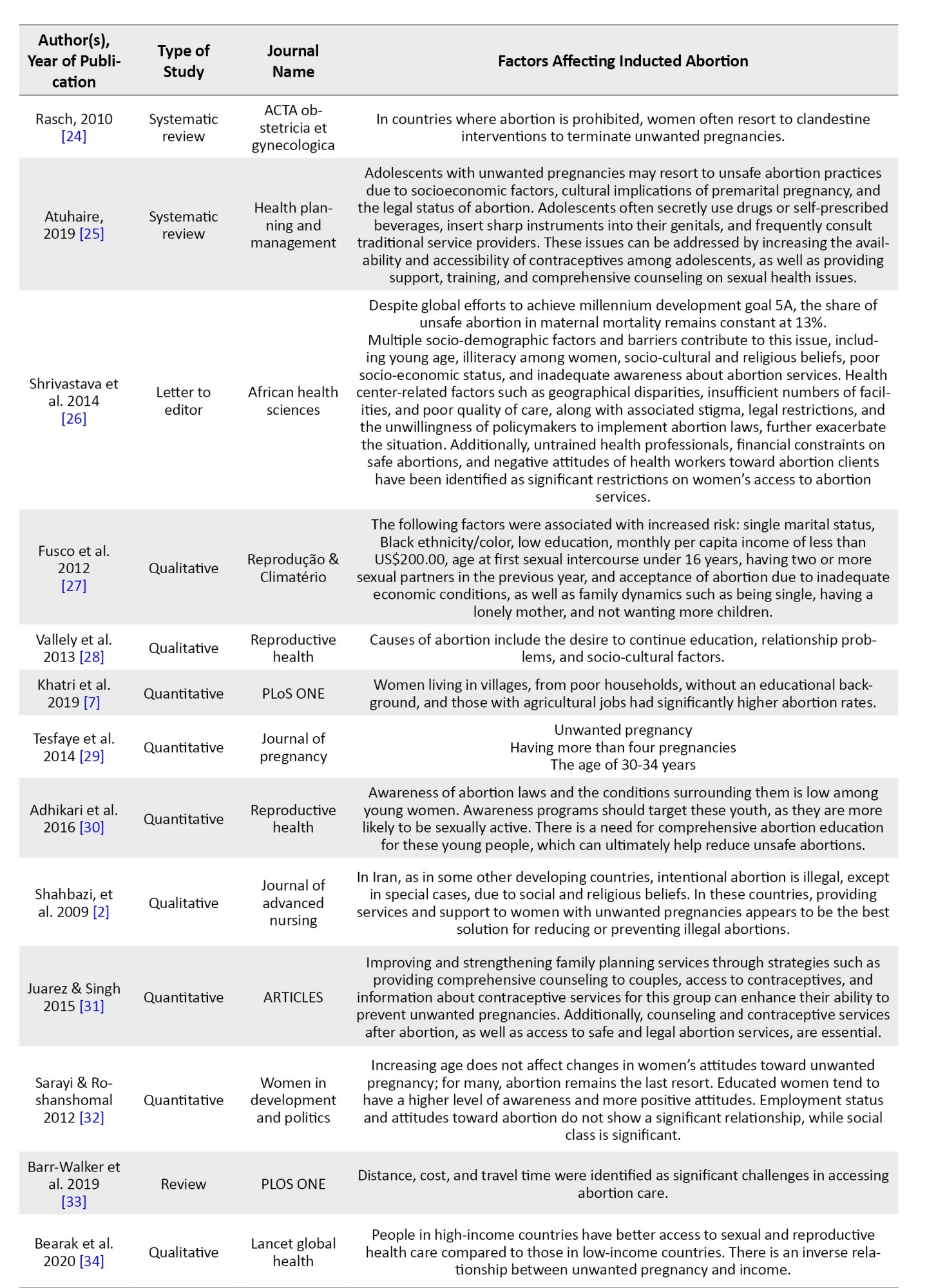

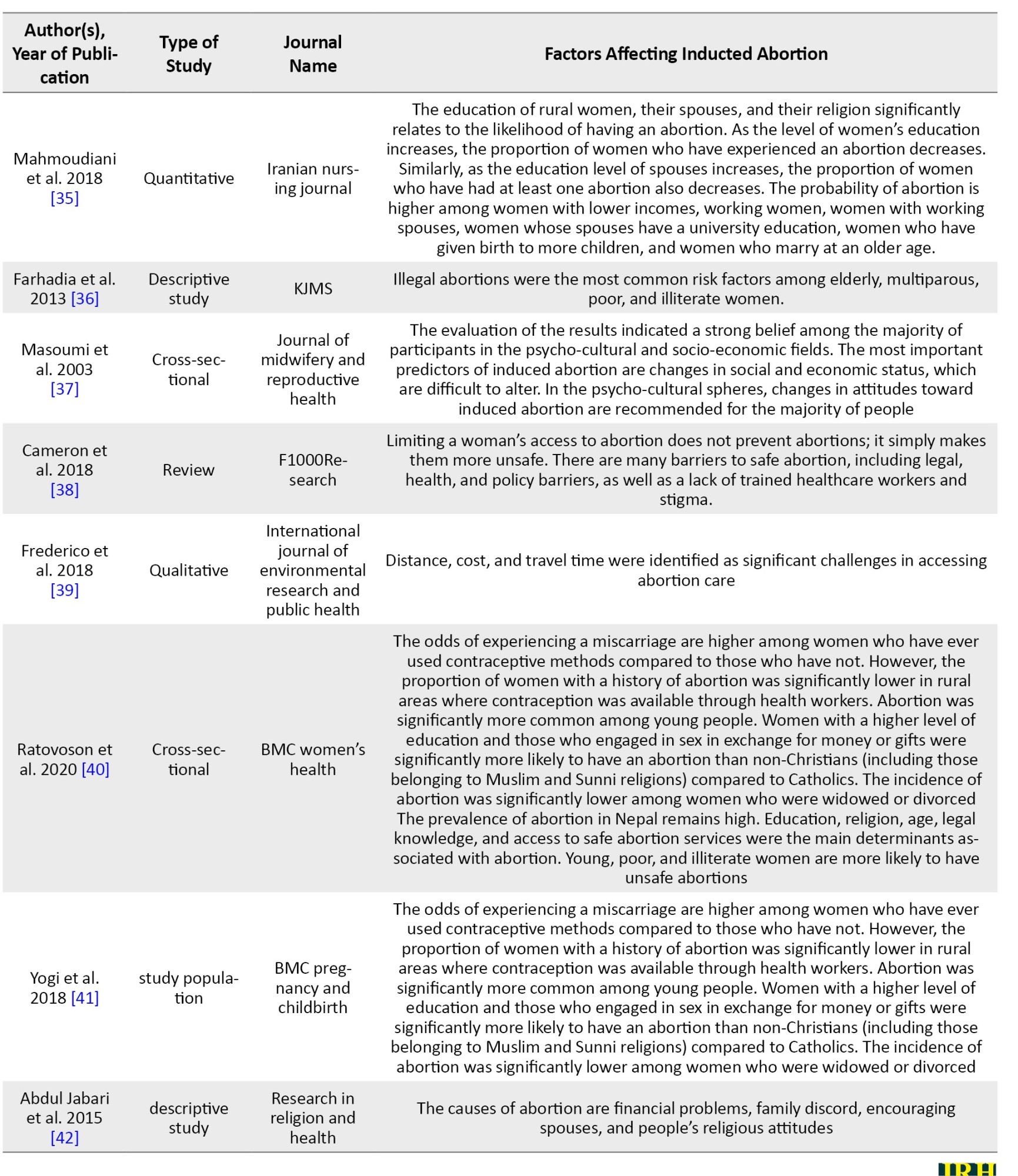

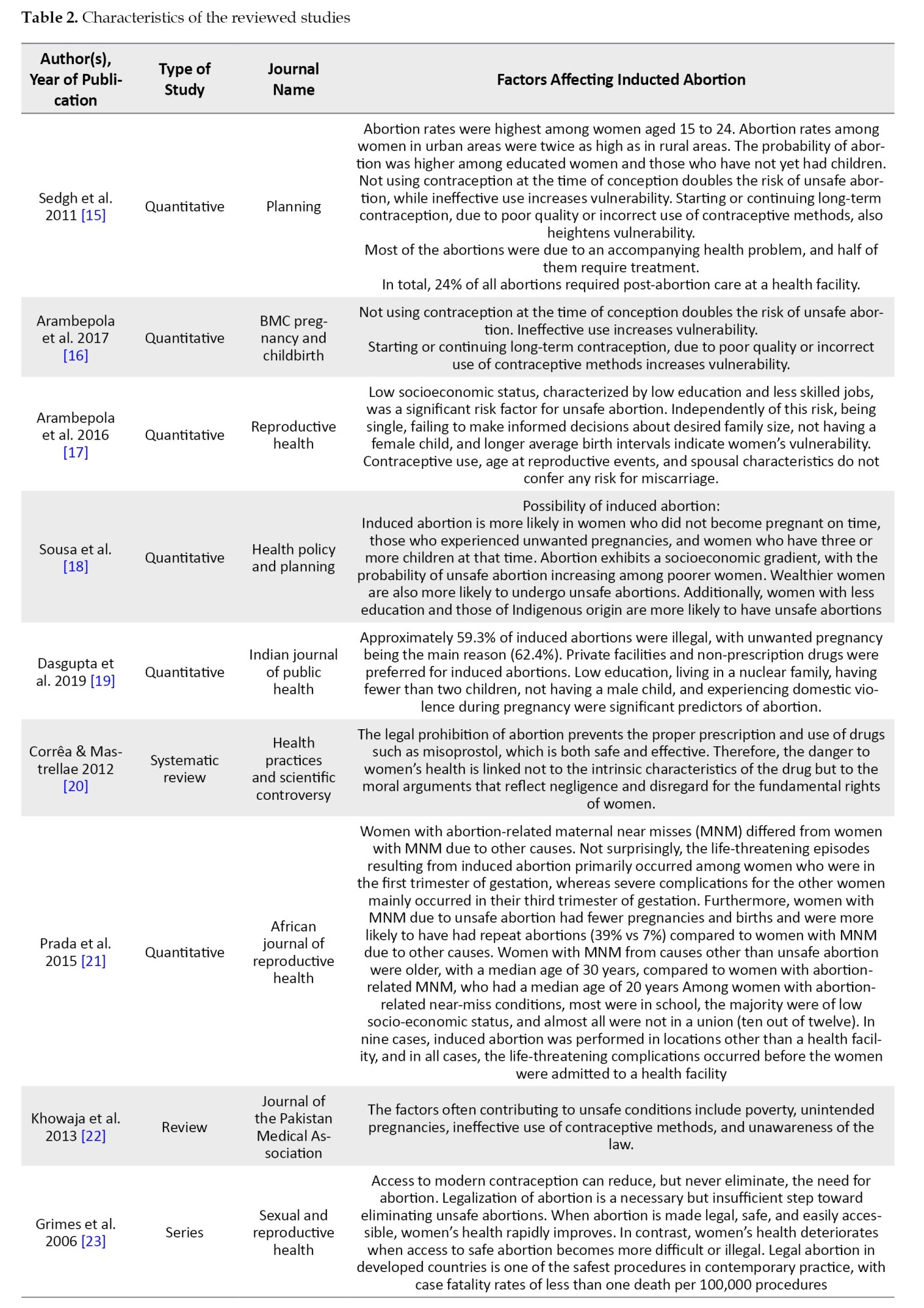

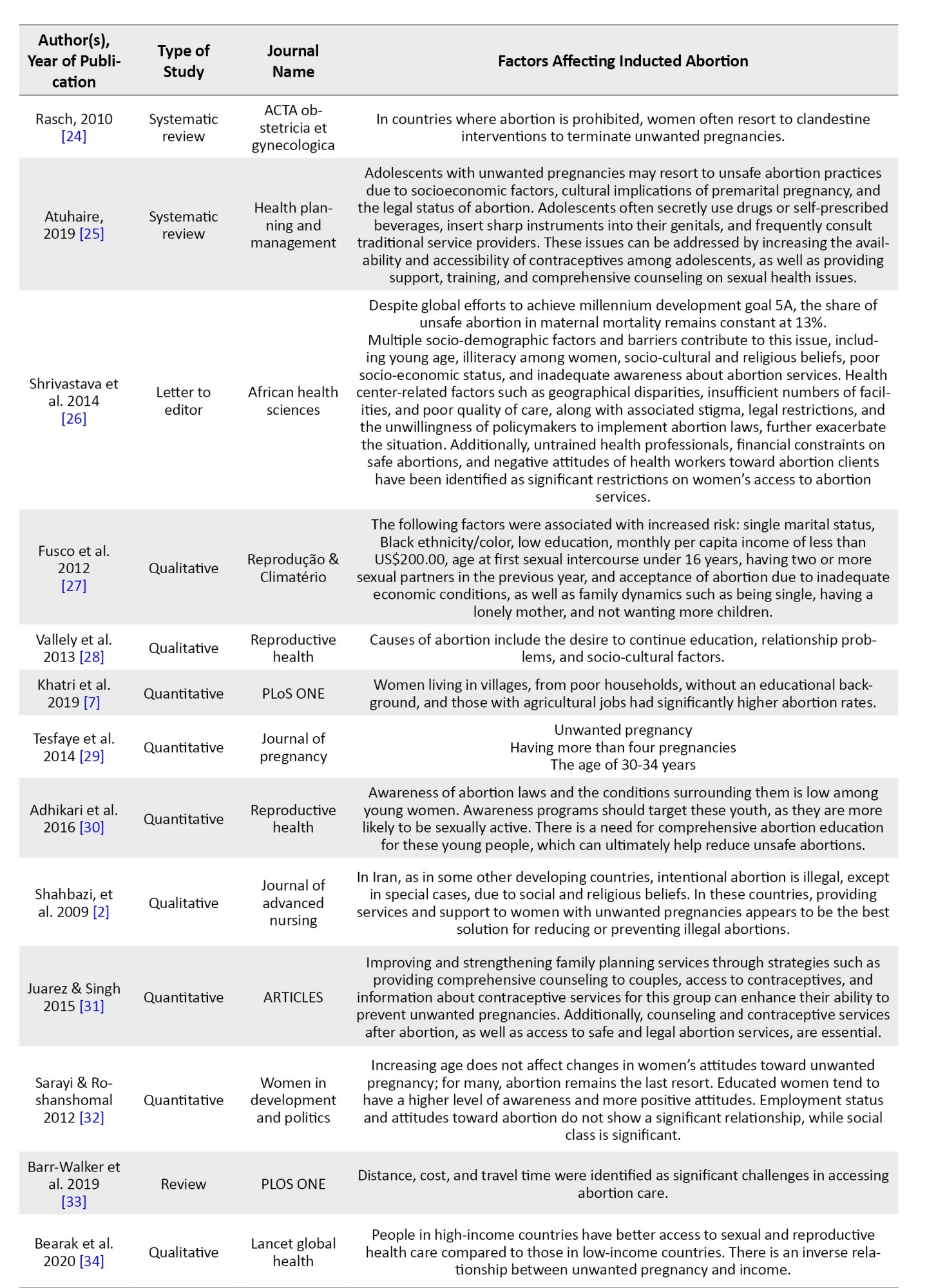

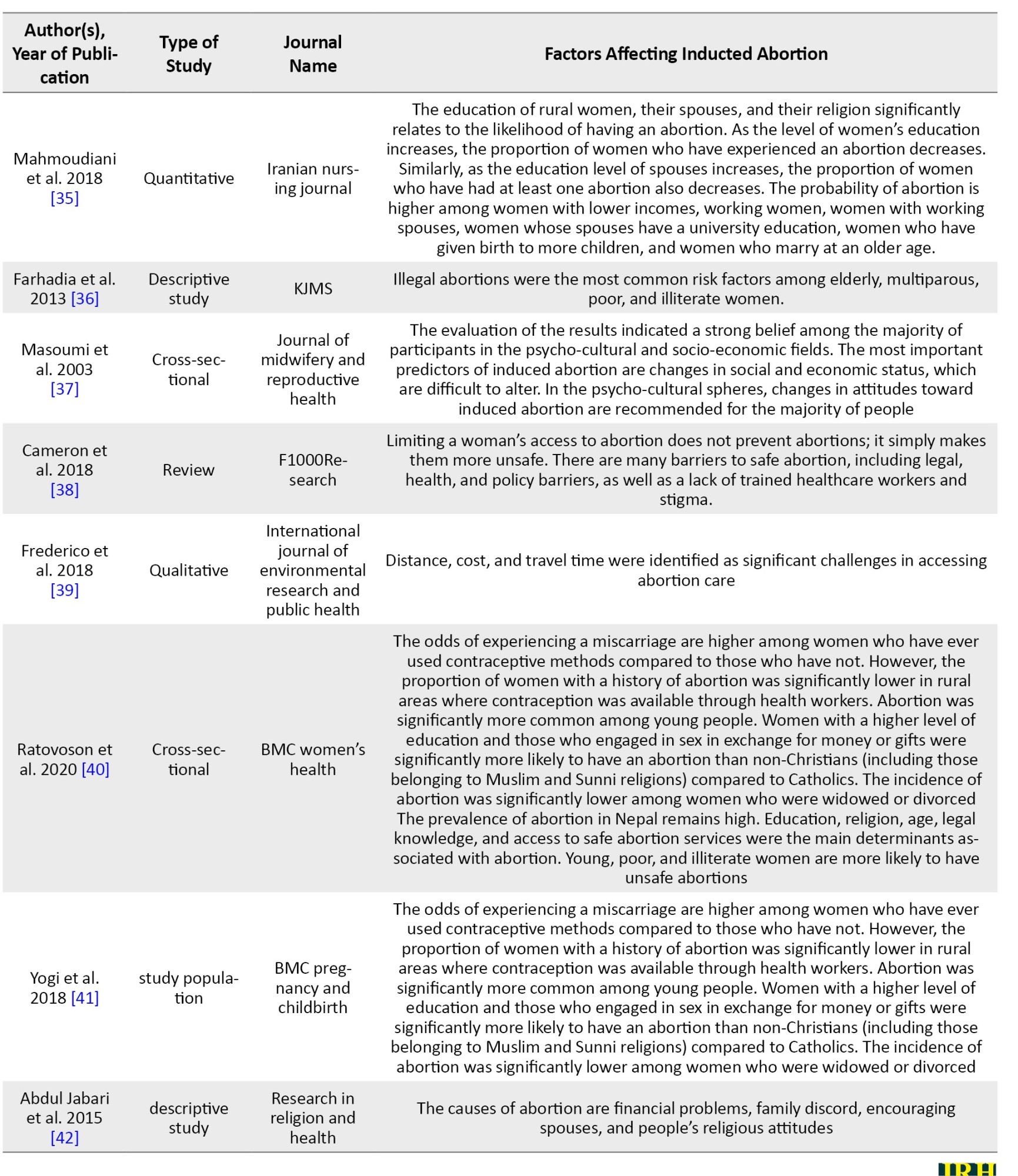

A total of 33 studies on factors affecting abortion were published from January 1, 2003, to March 20, 2023 (Table 2).

Three studies were in Persian (9%) and 30 were in English (91%). Two studies were published in the health policy and planning journal, three in the reproductive health journal, and three in the BMC pregnancy and childbirth journal and BMC women’s health journal. The maximum number of published studies was five in 2013, followed by four in 2018. Two studies were published annually in 2009, 2010, 2014, and 2015. Six studies (18.2%) used a review method, four (12.2%) used a qualitative method, 22(66.6%) used a quantitative method, and one (3%) used a letter to the editor-in-chief to collect data. The number of studies increased significantly in 2013 and 2018 but decreased in 2021 and 2022.

In general, the studies mentioned 33 factors affecting induced abortion, including the young age of women, celibacy, low socio-economic status, urbanization, low education level, low education level of husbands, no use of contraceptives, lack of access to contraceptives and reproductive health, incorrect use of contraceptives, long-term contraception, unemployment, having a low-level job, ignorance of abortion laws, lack of women’s participation in decision-making, unfavorable attitude of women’s health professionals to abortion, untrained health professionals, and illegitimate pregnancies, having multiple sexual partners, ban on abortion, socio-economic factors, cultural consequences, pregnancy before formal marriage, unwillingness of policymakers to implement abortion laws, primiparous women, the desire to continue education, religion, mental and cultural status of mothers, lack of access to safe abortion, family discord, encouragement from husbands, failure to make informed decisions about desired family size, long intervals between children, unintended pregnancy, geographic inequalities, having more than two children, not being pregnant with a male child, domestic violence, addiction, lack of financial means, the availability of abortion facilities, history of abortion, the feeling of failure, history of having an abnormal child, welfare seeking, perception of ease of abortion, ignorance of mental consequences of abortion, and ignorance of physical consequences of abortion.

The most frequent words in the search for factors affecting induced abortion were women’s education level (9 times), young age (9 times), unintended pregnancy (7 times), not using contraceptives (6 times), incorrect use of contraceptives (5 times), social, economic, and cultural factors (12 times), religion (4 times), husbands’ education level (4 times), women’s employment (3 times), and the number of children (4 times).

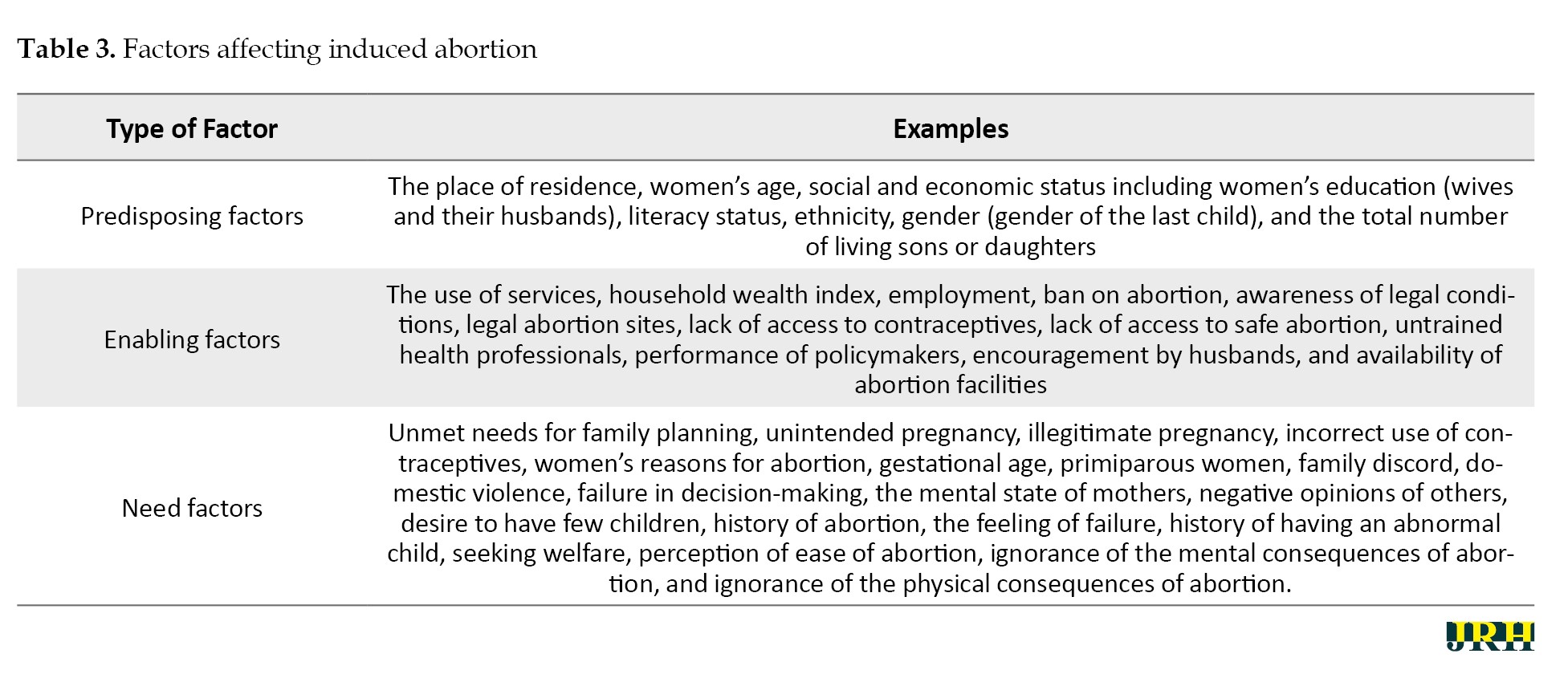

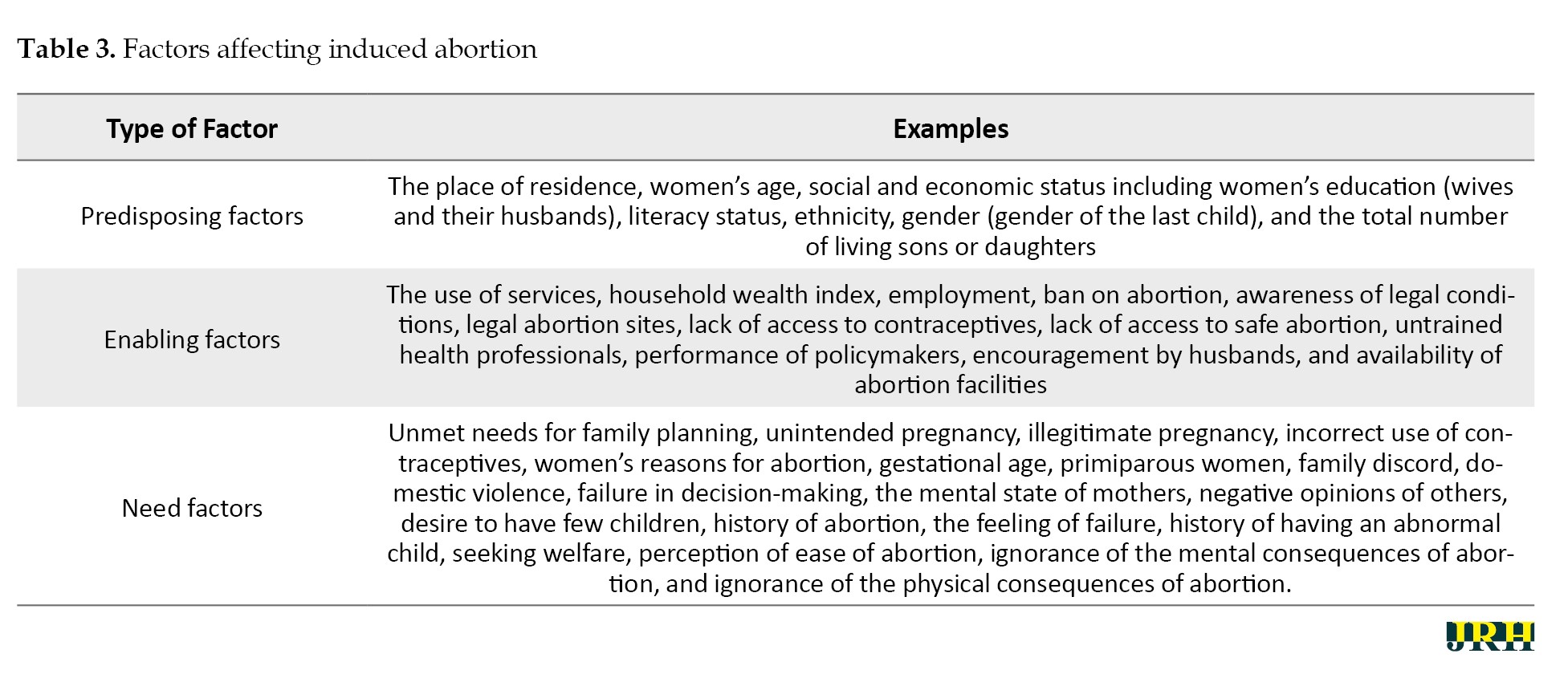

In this study, factors affecting induced abortion were categorized as predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors associated with the use or non-use of health services [15, 43].

Table 3 gives predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors induced abortion services.

Predisposing factors are existing conditions (not directly account for use) that predispose women to use or not use abortion services. Place of residence, women’s age, social and economic status, including women’s education (wives and their husbands), literacy status, ethnicity, gender (gender of the last child), and the total number of living sons or daughters were considered predisposing factors in this study. Enabling factors are conditions that facilitate or hinder induced abortion. In this study, the use of services, household wealth index, job, knowledge of legal conditions, and the site of legal abortion were the enabling factors.

Need factors are the needs or conditions that force women to use services. In this study, the need factors were unmet needs for family planning, unintended pregnancy, illegitimate pregnancy, incorrect use of contraceptives, women’s reasons for abortion, gestational age, primiparous women, family discord, domestic violence, primiparous women, failure in decision-making, and the mental state of mothers.

Discussion

Data analysis suggested that the predisposing factors influencing whether women use or do not use abortion services include the place of residence, women’s age, social and economic status, including women’s education (wives and their husbands), literacy status, ethnicity, gender (gender of the last child), and the total number of living sons or daughters. These findings were in line with the findings of studies conducted in Brazil [27] and Mexico [18], which indicate that under individual, economic, and social conditions, women face a range of threats that lead to induced abortion, highlighting that abortion does not occur in a social vacuum [44]. Changing couples’ attitudes toward married life, achieving higher levels of education, and improving overall well-being are positive developments; however, they are considered vulnerable and require intervention if they become the primary goals of marriage [45]. One of the social factors affecting the choice of abortion is women’s education level. According to the results, women with university education are less likely to experience abortion than women with lower education levels. This is in line with the findings of some previous studies [9, 46] but contrasts with the findings of some others [47]. The results of studies conducted in Vietnam [48], Africa [49], and Malawi [50] suggest that the differences in the impact of education level on abortion should be examined within the context of social structures that require intervention and cultural change. No crime can be controlled and explained regardless of its cultural, psychological, social, and economic aspects. The factors affecting abortion are similar to other social phenomena, and the responsible and public institutions must explain its various aspects and correct the behaviors of parents, which are often derived from the social background. This participation requires social health, including social skills and people’s ability to understand themselves and their health issues as members of the larger society [51]. The results of the study showed that there is a direct relationship between the number of children and the rate of abortion, specifically, as the number of children increases, the rate of abortion among women also increases. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Mexico [52].

In this study, the enabling factors include the use of services, household wealth index, employment status, knowledge of legal conditions, and the location of legal abortion services. In other words, if the economic and social factors affecting the family improve, other factors may lose their explanatory power. The results of most studies suggest that the experience of abortion is more prevalent among households with lower income levels [53]. Additionally, the results of this study showed that women who did not know where to obtain a safe abortion were more likely to use unsafe abortion facilities, regardless of their knowledge of the legal conditions of abortion. This is confirmed by the results of various studies [7, 54, 55], indicating that awareness of the locations of legal abortion is important for ensuring safe abortion services.

In the need factors section, unintended pregnancy was identified as the most important factor affecting induced abortion. The findings of studies indicate that unintended pregnancy is one of the most important causes of abortion. Low rates of contraception and unmet needs for family planning are important factors contributing to unintended pregnancy and possible causes of unsafe abortion [51]. Strengthening religious beliefs and fear of abortion complications significantly reduce the possibility of abortion. By promoting a particular lifestyle, religion serves as a defensive shield for individuals against harmful environmental factors. In other words, religious beliefs diminish people’s tendency to engage in risky behaviors, enabling them to address problems more effectively [56, 57]. This important issue requires changes in the structure of health services with more attention to religious foundations.

Conclusion

According to the results, the factors affecting fertility and abortion in society include cultural, environmental, social, economic, political, and religious factors. Personal motives, individuals’ attitudes, and their perceptions can affect people’s behavior at the micro level.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran (Code: IR.ARUMS.REC.1402.004).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Project administration: Farahnaz Ezati; Study design: Nazila Nejhaddadgar and Farahnaz Ezati; Writing the original draft: Farahnaz Ezati Data analysis, review, editing, and final approval All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all adolescents who participated in the research.

References

The loss and termination of pregnancy for any reason before the 22nd week of pregnancy is referred to as abortion [1]. As one of the safest gynecological surgical procedures, legal abortion is less dangerous than natural childbirth. However, unsafe abortion is one of the biggest neglected health problems in developing countries, being a major problem in women’s lives during their reproductive years. This type of abortion occurs outside legal systems and in environments with minimal medical standards, often performed by individuals who lack the necessary skills [2]. Accurate information regarding the number and physical, mental, psychological, social, and economic consequences of illegal abortion cannot be obtained in countries where abortion is not legal. Hospitals are not visited for secret complete abortions. Therefore, hospital data does not only represent the tip of the iceberg. Since abortion is seen as a reprehensible act, its guardian is always absent from healthcare programs. However, its complications are undeniable [3]. Some cases of hospitalization among young women in developing countries are rooted in the consequences of unsafe abortions. An estimated 22 million unsafe abortions are reported to occur annually worldwide, of which 98% take place in developing countries. Moreover, 5 million women suffer from the complications of unsafe abortion, including bleeding, infection, and damage to the reproductive system and abdominal organs [4].

Every year, approximately 25 million unsafe abortions occur worldwide, of which, 97% are reported in developing countries, with half of them occurring in Asia. Unsafe abortion plays an important role in maternal morbidity, disability, and mortality, largely due to post-abortion sepsis, hemorrhage, genital trauma, infection, and infertility. Recent estimates suggest that about 13% of global maternal deaths are attributed to unsafe abortion. Also, approximately seven million women undergo treatment due to complications resulting from unsafe abortion, and about five million women suffer disability as a result of such complications [5].

In Iran, abortion is allowed only if the mother’s life is in danger or the fetus is suffering from certain diseases; thus, induction abortion is performed. Apart from these circumstances, all other induced abortions are considered intentional abortions.

In recent years, various studies have been conducted in different countries about intentional abortion. In Jamaica, although abortion is unforgivable, there are certain customs for its acceptance in society. In southern Cameroon, while abortion is stigmatized, its social and moral consequences are considered less severe than those of an unplanned pregnancy, and despite this stigma, abortions are still performed in southern Cameroon [6]. In Thailand, abortion is illegal, except in cases where it is necessary for the mother’s health or if sexual assault is the cause of pregnancy; several methods are used for abortion in these cases. In Kenya, induced abortion is relatively common, especially among women, and young single urban women, who have limited access to pregnancy control facilities. In South Asia, Nepal has become a pioneer in the legalization, implementation, and scaling up of safe abortion services [7].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) report, most European countries allow legal abortion in all circumstances, except for Ireland and Andorra, which only allow abortion in the cases of saving the life of the mother, and England, which allows abortion only in cases of saving the mother’s life, at the mother’s request, or in instances of sexual assault. Malta is the only European country that does not allow abortion in any context [8].

Nearly 530,000 intentional abortions take place in Iran every year. Intended or criminal abortions constitute nearly one-third of all abortions, which is a significant proportion. According to official statistics, the abortion rate is about 8% in Ardabil Province. These abortions are identified by the health system, and there are no statistics on criminal abortions. Therefore, a better approach is to take measures that reduce the number of illegal abortions. The first way to do this is to reduce the number of unintended pregnancies. The number of illegal abortions can be significantly reduced if investments are made in this area. Some effective measures are comprehensive sexual health education, which provides accurate medical information about contraception, insurance coverage, access to contraceptives for those in need, and programs that address domestic violence and sexual abuse [9].

The key causes of abortion must be identified to reduce maternal mortality and unsafe abortions. Accordingly, this study was conducted to investigate the factors affecting induced and criminal abortions so that effective solutions can be provided based on the results for policy-making. Among the methods of review studies, the scoping review is an appropriate method to answer the questions “what” and “why” in a specific subject area. The scoping review method can be used when the main subject of the study and its documents are broad and complex or have not been extensively and comprehensively examined [10].

A scoping review is used for reasons, such as identifying the types of evidence of the subject under investigation, expressing the generality of the subject, identifying its key concepts, such as definitions and conceptual models, drawing a map of the relevant literature, identifying the research methods used in the field under investigation, examining the nature and scope of studies and research evidence produced, summarizing and publishing research findings, identifying and analyzing research gaps in the relevant literature, and determining the necessity of conducting a systematic review [10, 11]. Arksey and O’Malley’s six-stage methodological framework was used in this scoping review. These stages are:

1. Identifying the research questions

2. Identifying relevant studies using reliable databases and reviewing gray texts, theses, review articles, and references of studies in the research area

3. Selecting related studies from primary studies

4. Mapping out the data ::as char::ts and tables

5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

6. Including expert consultation

Unlike a systematic review that seeks to answer a specific question [12, 13], a scoping review seeks to answer several questions [10]. The questions of this study were as follows:

1. What factors cause women to have an abortion?

2. What are the most common factors?

Methods

This scoping review was conducted at Ardabil University of Medical Sciences in 2023. International databases, such as Springer, PubMed, Web of Science, Emerald, ScienceDirect, and Scopus, as well as national databases, such as Magiran and SID, and search engines, such as Google Scholar, were searched to find relevant studies. The keywords used for the search included MeSH terms, and the common keywords concerning the studied topic included as follows:

Causalities, multifactorial causality, multifactorial, reinforcing, causality, reinforcing factors, factor, causation, causations, enabling factors, enabling factor, factor, enabling factor, abortions, criminal, criminal abortion, abortion, illegal, illegal abortion, abortions (Table 1).

The inclusion criteria were all studies on factors affecting induced abortion from January 1, 2003, to March 20, 2023. The exclusion criteria were studies published in languages other than Persian and English, studies published after the end of March 20, 2023, and scientific references without full text. A total of 1275 studies were found in the initial search. After excluding duplicate studies and studies without full text, 653 studies were obtained for the review of titles and abstracts, of which 522 were excluded due to being unrelated. At this stage, 131 studies on factors affecting induced abortion were retained. After a thorough review of the studies, 93 were excluded due to irrelevance and low quality. After reviewing the references, five studies were added to the final review process. Finally, 33 review studies on factors affecting induced abortion were assessed (Figure 1). The data extraction form included the authors’ profiles, journal name, year of publication, purpose of the study, year of the study, type of study, data collection method, and factors affecting induced abortion. The data were analyzed using a qualitative approach and content analysis and were coded using MAXQDA software, version 20. The themes and sub-themes of each study were then extracted to define the relationship between the themes and identify the main concepts and models. The studies were evaluated using a valid checklist for the evaluation of review and research studies. The minimum and maximum scores that could be obtained were 1 and 15, respectively, and the minimum acceptable score was 10 [14]. A Kappa coefficient of 78% was obtained (P=0.00).

Results

A total of 33 studies on factors affecting abortion were published from January 1, 2003, to March 20, 2023 (Table 2).

Three studies were in Persian (9%) and 30 were in English (91%). Two studies were published in the health policy and planning journal, three in the reproductive health journal, and three in the BMC pregnancy and childbirth journal and BMC women’s health journal. The maximum number of published studies was five in 2013, followed by four in 2018. Two studies were published annually in 2009, 2010, 2014, and 2015. Six studies (18.2%) used a review method, four (12.2%) used a qualitative method, 22(66.6%) used a quantitative method, and one (3%) used a letter to the editor-in-chief to collect data. The number of studies increased significantly in 2013 and 2018 but decreased in 2021 and 2022.

In general, the studies mentioned 33 factors affecting induced abortion, including the young age of women, celibacy, low socio-economic status, urbanization, low education level, low education level of husbands, no use of contraceptives, lack of access to contraceptives and reproductive health, incorrect use of contraceptives, long-term contraception, unemployment, having a low-level job, ignorance of abortion laws, lack of women’s participation in decision-making, unfavorable attitude of women’s health professionals to abortion, untrained health professionals, and illegitimate pregnancies, having multiple sexual partners, ban on abortion, socio-economic factors, cultural consequences, pregnancy before formal marriage, unwillingness of policymakers to implement abortion laws, primiparous women, the desire to continue education, religion, mental and cultural status of mothers, lack of access to safe abortion, family discord, encouragement from husbands, failure to make informed decisions about desired family size, long intervals between children, unintended pregnancy, geographic inequalities, having more than two children, not being pregnant with a male child, domestic violence, addiction, lack of financial means, the availability of abortion facilities, history of abortion, the feeling of failure, history of having an abnormal child, welfare seeking, perception of ease of abortion, ignorance of mental consequences of abortion, and ignorance of physical consequences of abortion.

The most frequent words in the search for factors affecting induced abortion were women’s education level (9 times), young age (9 times), unintended pregnancy (7 times), not using contraceptives (6 times), incorrect use of contraceptives (5 times), social, economic, and cultural factors (12 times), religion (4 times), husbands’ education level (4 times), women’s employment (3 times), and the number of children (4 times).

In this study, factors affecting induced abortion were categorized as predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors associated with the use or non-use of health services [15, 43].

Table 3 gives predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors induced abortion services.

Predisposing factors are existing conditions (not directly account for use) that predispose women to use or not use abortion services. Place of residence, women’s age, social and economic status, including women’s education (wives and their husbands), literacy status, ethnicity, gender (gender of the last child), and the total number of living sons or daughters were considered predisposing factors in this study. Enabling factors are conditions that facilitate or hinder induced abortion. In this study, the use of services, household wealth index, job, knowledge of legal conditions, and the site of legal abortion were the enabling factors.

Need factors are the needs or conditions that force women to use services. In this study, the need factors were unmet needs for family planning, unintended pregnancy, illegitimate pregnancy, incorrect use of contraceptives, women’s reasons for abortion, gestational age, primiparous women, family discord, domestic violence, primiparous women, failure in decision-making, and the mental state of mothers.

Discussion

Data analysis suggested that the predisposing factors influencing whether women use or do not use abortion services include the place of residence, women’s age, social and economic status, including women’s education (wives and their husbands), literacy status, ethnicity, gender (gender of the last child), and the total number of living sons or daughters. These findings were in line with the findings of studies conducted in Brazil [27] and Mexico [18], which indicate that under individual, economic, and social conditions, women face a range of threats that lead to induced abortion, highlighting that abortion does not occur in a social vacuum [44]. Changing couples’ attitudes toward married life, achieving higher levels of education, and improving overall well-being are positive developments; however, they are considered vulnerable and require intervention if they become the primary goals of marriage [45]. One of the social factors affecting the choice of abortion is women’s education level. According to the results, women with university education are less likely to experience abortion than women with lower education levels. This is in line with the findings of some previous studies [9, 46] but contrasts with the findings of some others [47]. The results of studies conducted in Vietnam [48], Africa [49], and Malawi [50] suggest that the differences in the impact of education level on abortion should be examined within the context of social structures that require intervention and cultural change. No crime can be controlled and explained regardless of its cultural, psychological, social, and economic aspects. The factors affecting abortion are similar to other social phenomena, and the responsible and public institutions must explain its various aspects and correct the behaviors of parents, which are often derived from the social background. This participation requires social health, including social skills and people’s ability to understand themselves and their health issues as members of the larger society [51]. The results of the study showed that there is a direct relationship between the number of children and the rate of abortion, specifically, as the number of children increases, the rate of abortion among women also increases. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Mexico [52].

In this study, the enabling factors include the use of services, household wealth index, employment status, knowledge of legal conditions, and the location of legal abortion services. In other words, if the economic and social factors affecting the family improve, other factors may lose their explanatory power. The results of most studies suggest that the experience of abortion is more prevalent among households with lower income levels [53]. Additionally, the results of this study showed that women who did not know where to obtain a safe abortion were more likely to use unsafe abortion facilities, regardless of their knowledge of the legal conditions of abortion. This is confirmed by the results of various studies [7, 54, 55], indicating that awareness of the locations of legal abortion is important for ensuring safe abortion services.

In the need factors section, unintended pregnancy was identified as the most important factor affecting induced abortion. The findings of studies indicate that unintended pregnancy is one of the most important causes of abortion. Low rates of contraception and unmet needs for family planning are important factors contributing to unintended pregnancy and possible causes of unsafe abortion [51]. Strengthening religious beliefs and fear of abortion complications significantly reduce the possibility of abortion. By promoting a particular lifestyle, religion serves as a defensive shield for individuals against harmful environmental factors. In other words, religious beliefs diminish people’s tendency to engage in risky behaviors, enabling them to address problems more effectively [56, 57]. This important issue requires changes in the structure of health services with more attention to religious foundations.

Conclusion

According to the results, the factors affecting fertility and abortion in society include cultural, environmental, social, economic, political, and religious factors. Personal motives, individuals’ attitudes, and their perceptions can affect people’s behavior at the micro level.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran (Code: IR.ARUMS.REC.1402.004).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Project administration: Farahnaz Ezati; Study design: Nazila Nejhaddadgar and Farahnaz Ezati; Writing the original draft: Farahnaz Ezati Data analysis, review, editing, and final approval All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all adolescents who participated in the research.

References

- Costescu D, Guilbert E, Bernardin J, Black A, Dunn S, Fitzsimmons B, et al. Medical abortion. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2016; 38(4):366-89. [DOI:10.1016/j.jogc.2016.01.002] [PMID]

- Shahbazi S, Fathizadeh N, Taleghani F. [The process of illegal abortion: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Payesh. 2011; 10(2):183-95. [Link]

- Mohammadzadeh F, Fallahian M. [The induced abortion conditions in Taleghani hospital depended to Shahid Beheshti Medical University 2000-2001 (Persian)]. The Journal of Legal Medicine. 2002; 32:190-93. [Link]

- Nosrati S, Karimi F. Afiat M, Emami Moghadam Z. [An overview of the various dimensions of abortion in international human rights documents (Persian)]. Navid No. 24(77):98-107. [DOI:10.22038/nnj.2021.51699.1229]

- World Health Organization. Safe abortion: Technical and policy guidance for health systems. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Link]

- Rostami S, Abdi F, Ahmadi M, Wadadhir AA. [Comparative study of abortion laws in the countries of the world (Persian)]. History of Medicine. 2013; 5(17):79-111. [Link]

- Khatri RB, Poudel S, Ghimire PR. Factors associated with unsafe abortion practices in Nepal: Pooled analysis of the 2011 and 2016 Nepal Demographic and Health Surveys. Plos One. 2019; 14(10):e0223385. [DOI:10.1371/ journal.pone.0223385] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fathnezhad Kazemi A, Sharifi N, Khazaeian S, Ramazankhani A. [Various aspects of abortion and related policies in the world (Persian)]. Medical Ethics Journal. 2017; 11(39):75-89. [Link]

- Darabi F, Yaseri M, Kaveh MH, Khalajabadi Farahani F, Majlessi F, Shojaeizadeh D. The effect of a theory of planned behavior-based educational intervention on sexual and reproductive health in Iranian adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2017; 17(4):e00400. [PMID]

- Mosadeghrad AM, Rahimitabar P. [Health system governance in Iran: A comparative study (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences. 2019; 26(9):10-28. [Link]

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2015; 13(3):141-6. [DOI:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050] [PMID]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8(1):19-32. [DOI:10.1080/1364557032000119616]

- Mosadeghrad AM, Karimi F, Ezzati F. [Health system resilience: A conceptual review (Persian)]. Hakim. 2020; 23(4):463-86. [Link]

- Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Waye Perry B. Knowledge transfer and exchange: Review and synthesis of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly. 2007; 85(4):729-68. [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00506.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sedgh G, Rossier C, Kaboré I, Bankole A, Mikulich M. Estimating abortion incidence in Burkina Faso using two methodologies. Studies in Family Planning. 2011; 42(3):147-54. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00275. x] [PMID]

- Arambepola C, Rajapaksa LC. Risk of unsafe abortion associated with long-term contraception behaviour: A case control study from Sri Lanka. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017; 17(1):205. [DOI: 10.1186/s12884-017-1376-7] [PMID]

- Arambepola C, Rajapaksa LC, Attygalle D, Moonasinghe L. Relationship of family formation characteristics with unsafe abortion: Is it confounded by women's socio-economic status? - A case-control study from Sri Lanka. Reprod Health. 2016; 13(1):75. [DOI: 10.1186/s12978-016-0173-5] [PMID]

- Sousa A, Lozano R, Gakidou E. Exploring the determinants of unsafe abortion: Improving the evidence base in Mexico. Health Policy and Planning. 2010; 25(4):300-10. [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czp061] [PMID]

- Dasgupta P, Biswas R, Das DK, Roy JK. Occurrence and predictors of abortion among women of the reproductive age group in a block of Darjeeling District, West Bengal, India. Indian Journal of Public Health 2019; 63:298-304. [DOI: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_316_18] [PMID]

- Corrêa MC, Mastrella M. [Abortion and misoprostol: Health practices and scientific controversy (Portuguese)]. Cien Saude Colet. 2012; 17(7):1777-84. [DOI: 10.1590/s1413-81232012000700016] [PMID]

- Prada E, Bankole A, Oladapo OT, Awolude OA, Adewole IF, Onda T. Maternal near-miss due to unsafe abortion and associated short-term health and socio-economic consequences in nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2015; 19(2):52-62. [PMID]

- Khowaja SS, Pasha A, Begum S, Mustafa MU. Ray of hope: opportunities for reducing unsafe abortions!Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2013; 63(1):100-2. [PMID]

- Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, Romero M, Ganatra B, Okonofua FE, et al. Unsafe abortion: The preventable pandemic. Lancet. 2006; 368(9550):1908-19. [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6] [PMID]

- Rasch V. Unsafe abortion and postabortion care - an overview. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011; 90(7):692-700. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01165. x] [PMID]

- Atuhaire S. Abortion among adolescents in Africa: A review of practices, consequences, and control strategies. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2019; 34(4): e1378-e1386. [DOI: 10.1002/hpm.2842] [PMID]

- Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Unsafe abortion: A cruel way of birth control. African Health Sciences. 2014; 14(2):487-8. [DOI: 10.4314/ahs. v14i2.29] [PMID]

- Fusco CLB. [Unsafe abortion: A serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population (Portuguese)]. Reproduc¸ão & Climate’rio. 2013; 28(1):2-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.recli.2013.04.001]

- Vallely LM, Homiehombo P, Kelly-Hanku A, Whittaker A. Unsafe abortion requiring hospital admission in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea--a descriptive study of women's and health care workers' experiences. Reproductive Health. 2015; 12:22. [DOI: 10.1186/s12978-015-0015-x] [PMID]

- Tesfaye G, Hambisa MT, Semahegn A. Induced abortion and associated factors in health facilities of Guraghe zone, southern Ethiopia. Journal of Pregnancy. 2014; 2014:295732. [DOI: 10.1155/2014/295732] [PMID]

- Adhikari, R. Knowledge on legislation of abortion and experience of abortion among female youth in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health. 2016; 13:48. [DOI.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0166-4] [PMID]

- Juarez F, Singh S. Incidence of induced abortion by age and state, Mexico, 2009: New estimates using a modified methodology. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012; 38(2):58-67. Erratum in: Int Perspect Sex Reproductive Health. 2013; 39(1):46. [DOI: 10.1363/3805812] [PMID]

- Sarayi H, Roshanshomal P. [Examining social factors affecting pregnant women’s attitude towards induced abortion (Persian)]. Woman in Development & Politics. 2012; 10(2): 5-23. [DOI: 10.22059/jwdp.2012.28685]

- Barr-Walker J, Jayaweera RT, Ramirez AM, Gerdts C. Experiences of women who travel for abortion: A mixed methods systematic review. PLoS One. 2019; 14(4): e0209991. [DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209991] [PMID]

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, Moller AB, Tunçalp Ö, Beavin C, Kwok L, Alkema L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Global Health. 2020; 8(9): e1152-e1161. [DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X (20)30315-6] [PMID]

- Mahmoudiani S, Yar Ahmadi A, Javadi A. [The prevalence and influential factors of abortion in the women in the rural areas of Fars Province, Iran (2015) (Persian). Iran Journal of Nursing (IJN). 2018; 31:115: 51-61. [DOI:10.29252/ijn.31.115.51]

- Farhadia S, Shandana B, Samina Z, Rehana R. Risk factors of illegal induce abortion. KJMS. 2013; 6(2): 271-4. [Link]

- Masoumi SZ, Khani S, Kazemi F, Mir-Beik Sabzevari B, Faradmal J. Attitude of reproductive age women towards factors affecting induced abortion in Hamedan, Iran. Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health. 2016; 4(3):696-703. [DOI: 10.22038/jmrh.2016.7119]

- Cameron S. Recent advances in improving the effectiveness and reducing the complications of abortion [version 1; referees: 3 approved] F1000Research 2018, 7(F1000 Faculty Rev):1881. [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.15441.1]

- Frederico M, Michielsen K, Arnaldo C, Decat P. Factors influencing abortion decision-making processes among young women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(2):329. [DOI: 10.3390/ijerph15020329] [PMID]

- Ratovoson R, Kunkel A, Rakotovao JP, Pourette D, Mattern C, Andriamiadana J, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and complications of induced abortion in ten districts of Madagascar: Results from a cross-sectional household survey. BMC Women’s Health. 2020; 20(1):96. [DOI: 10.1186/s12905-020-00962-2] [PMID]

- Yogi A, K C P, Neupane S. Prevalence and factors associated with abortion and unsafe abortion in Nepal: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1):376. [DOI: 10.1186/s12884-018-2011-y] [PMID]

- Abdoljabbari M, Karamkhani M, Saharkhiz N, Pourhosseingholi M, Khoubestani MS. Study of the effective factors in women’s decision to make abortion and their belief and religious views in this regard. Journal of Religion and Health. 2016; 2(4):44-54. [Link]

- Andersen R, Davidson P. Improving access to care in america: individual and contextual indictators. In: Andersen R, Rice T, Kominski G, editors. Changing the US health care system: Key issues in health services, policy and management. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. [Link]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 10 August 1971. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Svanemyr J, Amin A, Fogstad H, Say L, Girard F, et al. Twenty years after international conference on population and development: Where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015; 56(1 Suppl):S1-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.015] [PMID]

- Tazakori Z, Molaie B, Ehdaie-vand F, Amani F, Mardi A, Foladi N. [Factors affecting abortion in patients referring to hospitals in Ardebil (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Care. 2008; 10(4):19-24. [Link]

- Erfani A. Induced abortion in Tehran, Iran: Estimated rates and correlates. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011; 37(3):134-42. [DOI:10.1363/3713411] [PMID]

- Oyefara JL. Power dynamics, gender relations and decision-making regarding induced abortion among university students in Nigeria. African Population Studies. 2017; 31(1):3324-32. [DOI:10.11564/31-1-991]

- Cockrill K, Upadhyay UD, Turan J, Greene Foster D. The stigma of having an abortion: Development of a scale and characteristics of women experiencing abortion stigma. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2013; 45(2):79-88. [DOI:10.1363/4507913] [PMID]

- Thapa S, Neupane S. Abortion clients of a public-sector clinic and a non-governmental organization clinic in Nepal. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 2013; 31(3):376-87. [DOI:10.3329/jhpn.v31i3.16830] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zuo X, Yu C, Lou C, Tu X, Lian Q, Wang Z. Factors affecting delay in obtaining an abortion among unmarried young women in three cities in China.Asia-Pacific. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2015; 30(1):35-50. [DOI:10.18356/758e5c7a-en]

- Henshaw SK, Singh S, Haas T. 1999. The incidence of abortion worldwide. International Family Planning Perspectives 25(Suppl.): S30–8. [PMID]

- NeJhaddadgar N, Ziapour A, Jafarzadeh M, Ezzati F, Rezaei F, Darabi F. Explaining barriers to childbearing using the risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) strategy: Based on action research. Health Science Reports. 2023; 6(10):e1606. [DOI:10.1002/hsr2.1606] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Thapa S, Sharma SK, Khatiwada N. Women's knowledge of abortion law and availability of services in Nepal. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2014; 46(2):266-77. [DOI:10.1017/S0021932013000461] [PMID]

- Thapa S, Sharma SK. Women's awareness of liberalization of abortion law and knowledge of place for obtaining services in Nepal. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2015; 27(2):208-16. [DOI:10.1177/1010539512454165] [PMID]

- Darabi F, Momeni Shabanı S, Mardi A, Nejhaddadgar N. Practical steps of intervention design to increase the childbearing desires: An intervention mapping approach. Journal of Research and Health. 2023; 13(6):407-16. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.13.6.821.1]

- Darabi F, Yaseri M. Intervention to improve menstrual health among adolescent girls based on the theory of planned behavior in Iran: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2022; 55(6):595-603. [DOI:10.3961/jpmph.22.365] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

● Health Systems

Received: 2024/01/30 | Accepted: 2024/07/13 | Published: 2025/01/1

Received: 2024/01/30 | Accepted: 2024/07/13 | Published: 2025/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |