Volume 15, Issue 2 (March & April 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(2): 185-196 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: (IR.IAU.WT.REC.1402.159).

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Irani Z, Kabirri A, Rahimi E, Bayat Varkeshi M, Nazari Ghale Toli F. Relationship Between Psychology and Religious Attitude: the Moderating Role of Life Goal in Adolescence With Self-harm. J Research Health 2025; 15 (2) :185-196

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2502-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2502-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanity, West Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanity, Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanity, Allameh Tabatabai University, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanity, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,tabasom0144@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanity, Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanity, Allameh Tabatabai University, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanity, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 876 kb]

(592 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3442 Views)

Full-Text: (1042 Views)

Introduction

Self-harm has emerged as a significant global public health issue, impacting approximately one million individuals worldwide. Among adolescents, the prevalence of self-harm ranges from 10 to 20% throughout their lifetime. Furthermore, self-harm tends to initiate and reach its peak during adolescence [1]. It has been defined as deliberate self-poisoning or injury regardless of the apparent motivation behind the act. This behavior is closely linked to an increased likelihood of future suicide [2]. Despite being classified as a high-risk group, it is crucial to identify the factors associated with a reduced risk of self-harm among young people and gain insights into why this is the case. Understanding and addressing these aspects are essential in the prevention of self-harm within this population [3].

Hence, self-harm behaviors, in terms of reduced feelings of defeat and internal entrapment, were indirectly associated with psychological well-being [4]. Psychological well-being, which encompasses positive feelings, thoughts, and strategies, has been linked to better physical health and longer lifespan. Better physical health and longer lifespan have been associated with psychological well-being, which entails positive emotions, thoughts, and coping mechanisms [5]. A person with psychological well-being must have the following six characteristics: Self-acceptance and self-peace, positive relationships with others, self-thinking and behavior, mastering the environment, having a purpose and meaning in life, and evaluating life as a learning and development process [6]. Recognizing its impact on public health, promoting psychological well-being in adolescents is now a global priority [7]. It is plausible that greater psychological well-being can shield adolescent individuals from intentional self-harm and self-poisoning by decreasing feelings of defeat and entrapment and acting as a buffer against the development of self-harming intentions [8]. Stopping self-harm is associated with better psychological well-being and higher role functioning [9].

Adolescents who have engaged in self-harm in the past were found to have a higher likelihood of reporting lower levels of psychological well-being [10, 11]. There is a theoretical model that explains why religious adolescents display less risky behavior compared to nonreligious adolescents, consisting of four mechanisms. These mechanisms include the influence of religion on the availability of opportunities for engaging in risky behavior, the appeal of risky behavior, the moral acceptability of risky behavior, and the ability to exercise self-control over impulses. While these mechanisms are not exclusive to religions, our model identifies three aspects of religion that can foster them [12].

Religious attitude comprises four aspects of religiosity: Belief, personal experiences, consequences, and rituals. These aspects can have a significant emotional and psychological influence on individuals, particularly adolescents, ultimately leading to increased self-confidence and mental well-being [13]. A study has presented evidence supporting the protective effect of certain religious practices on self-harm and suicidal behaviors in adolescents [14]. Other studies have also highlighted the significant role of preventive education focused on religiosity and moral foundations in reducing risky behaviors, particularly in teenage girls struggling with addiction [15]. Grover et al. demonstrated that individuals who engage in self-harm have a lower tendency to use positive religious coping strategies and a higher tendency to employ negative religious coping strategies [16]. In addition, both spirituality and health-related behaviors have a positive relationship with psychological well-being [17].

Religion can establish a belief system that encompasses finding meaning in life, experiencing a positive sense of self, and recognizing one’s deservingness of respect [18]. Encouraging young individuals to discover a purpose in life contributes to their positive development [19]. Heng et al. found that nearly all adolescents believed that having a purpose provides a foundation and direction in life, and more than half mentioned that it leads to increased happiness [20]. Furthermore, prominent scholars have proposed theories suggesting that a sense of purpose in life may be especially common among highly talented adolescents [21]. Bronk et al. indicated that high-ability early and late adolescents demonstrated a similar prevalence of purpose compared to their peers with more typical abilities. However, high-ability youth reported adopting self-centered life goals more than their peers and identified different inspiring life purposes [22]. Also, the goal in life mediates the relationship between religious attitude and mental well-being [23].

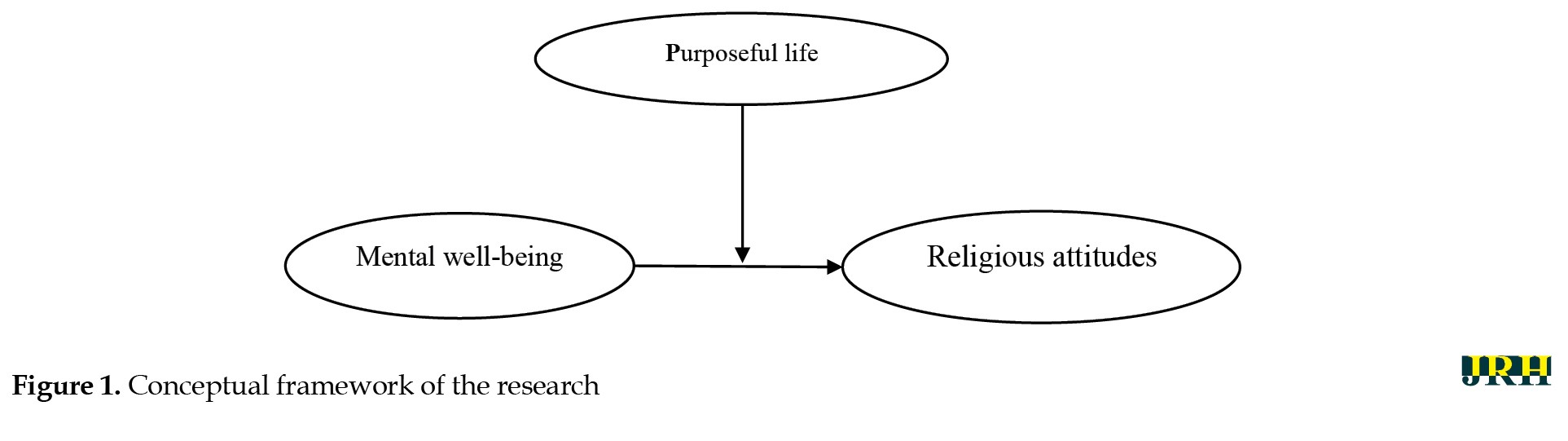

Due to the special period of their development, teenagers have to face many biological, academic and social transitional events that may force them to perform risky behaviors, such as self-harm. Since these behaviors are associated with many harms to individuals and society and may become contagious among adolescents, it is necessary to address the factors that can help this group of adolescents. Despite the significance of this topic, there have been limited studies conducted in this particular field and none have explored the correlation between the psychological well-being and religious attitudes of self-harming adolescents in relation to their life purposes. Consequently, a research gap exists and this study offers a new perspective. Accordingly, this research aimed to investigate the relationship between psychological well-being and religious attitudes while considering the mediating role of life purposes among self-harming adolescents. Figure 1 illustrates the researcher’s conceptual model for this study.

Methods

Research design

This descriptive-correlational utilized the cross-sectional approach along with structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population comprised all adolescents, both male and female, who had engaged in self-harm behaviors in Tehran from July to October 2023. The presence of these behaviors was verified by expert psychologists at research clinics.

Sample and sampling method

The research involved 250 adolescents who had previously participated in self-harm activities and were selected using purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling method, in which based on specific assumptions, qualified people (teenagers with self-harm) are selected as a sample. Since the current research was conducted on a specific group of teenagers, the sampling method should have been chosen purposefully. Therefore, the necessary characteristics for selecting individuals as samples were first identified. Then, eligible teenagers were selected. Among the limitations of this method that may introduce bias, the purposeful sampling method for data collection is particularly susceptible to research bias. If chosen incorrectly, the sample size may not be representative of the population. However, to avoid bias in the sample size, the researcher carefully established the entry and exit criteria.

The suitability of the sample size was determined using the formulas provided by Cohen [24] and Westland [25] for estimating the required sample size in SEM studies. The decision considered the amount of variables observed and latent variables in the model, the anticipated impact size, and the intended probability and statistical power. The following values were used to calculate the sample size: Effect size: 0.3, statistical power level: 0.8, latent variables: 3, observed variables: 129, and probability level: 0.01. Through this calculation, the researcher determined that the sample size would be 161 people. However, due to the risk of a significant reduction in the research sample, the researcher decided to aim for a sample size of 200 individuals to prevent attrition.

The requirements for participation in the study encompassed having a documented psychological history of self-harm behavior, providing informed consent, receiving consent from the parents of the adolescents, and possessing adequate literacy and comprehension skills to respond to the inquiries. To be eligible for participation, participants had to be over 19 years old and free from any physical or mental conditions that hindered their ability to respond. Additionally, failing to answer more than eight questions resulted in withdrawal from the study. Initially, the researchers obtained the required permissions from their university to conduct the study. Subsequently, with the assistance of university professors, the researchers were connected to ten psychology and counseling clinics in Tehran.

The purpose of reserving the clinics’ names was to safeguard the information. These specific clinics were selected based on their seamless coordination and execution of research, as well as the potential for collaboration in engaging with youths displaying self-harming behaviors. Subsequently, the researcher visited the clinics and collaborated with their management department to carry out the research project. Then, a message was dispatched to the families who had a child with a previous self-harm history and had utilized counseling and treatment services at the research clinics, inviting them to participate in the study. The next step involved sending more comprehensive information about the study to the participants through social media platforms. This information included the objectives of the research, the necessary permits, and guidelines regarding adherence to ethical principles. Participants were informed that none of the research materials contained their personal information and that adolescents could withdraw from the study at any time if they wished to do so. The research process and completion of online questionnaires took three months. A total of 196 out of 200 questionnaires were used for analysis, while four questionnaires were excluded for being incomplete or intentionally erroneous. Participants filled out the questionnaires themselves online. To comply with ethical principles, a consent form indicating their willingness to participate was obtained from the participants before administering the questionnaires. They were informed that participation in the research was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. It was also explained to them that these tests did not contain any identifying information.

Tools

Ryff’s psychological well-being scales (PWB)

This 84-question self-assessment questionnaire was developed by Ryff in 1980 to measure psychological well-being [26]. It has six factors, including self-acceptance, positive relationship with others, autonomy, purposeful life, personal growth and mastering the environment, each containing 14 questions. The questionnaire utilizes a six-point Likert scale, ranging from one (completely disagree) to five (completely agree), and the component scores range from 14 to 86. Ryff [26] reported that Cronbach’s α coefficients for the scale components are as follows: Self-acceptance is equal to 0.93, positive relationships with others are equal to 0.91, autonomy is equal to 0.86, objective life is equal to 0.90, personal growth is equal to 0.90 and mastery of the environment obtained a value of 0.87. Iranian researchers have documented that the scale’s internal consistency ranges between 0.76 and 0.83 [27]. This research found that the self-acceptance dimension had a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.893, while the positive relationship with others had a coefficient of 0.774. Autonomy had a coefficient of 0.807, objective life had a coefficient of 0.782, personal growth had a coefficient of 0.749 and mastery of the environment had a coefficient of 0.749. Moreover, the Cronbach α coefficient of the whole scale was determined to be 0.631.

Religious attitude questionnaire (RAQ)

This questionnaire is a 25-question self-assessment scale designed by Sadeghi et al to measure religious attitudes [28]. This questionnaire is scored on a five-point Likert scale (zero to four) and the range of scores is from 0 to 100. A score of 76 to 100 is classified as excellent religious attitude, 51 to 75 as good, 26 to 50 as average, and 25 as low as weak religious attitude. The reliability of the scale was determined using the correlation method and was found to be 0.80, which was confirmed by the manufacturer of the scale. The scale’s internal consistency was examined by researchers in Iran, who determined its reliability using Cronbach’s α with a value of 0.67 [29]. In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.831.

Purpose-in-life questionnaire (PIL)

The PIL, consisting of 20 questions, was developed and revised by Maholick and Crumbaugh in 1969. The main objective of this questionnaire is to assess an individual’s perception and significance of their purpose or meaning in life [30]. The scale has a minimum score of 20 and a maximum score of 100. If a person’s score is <50, it indicates aimlessness in life; conversely, if the score is higher than 50, it suggests that the person has a clear goal in life. Iranian researchers have reported that the scale’s internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.92 [31]. In this research, the researcher found the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale to be 0.899.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD were used to describe the data and the results were reported as frequency distribution tables. The second part included the analysis of the research hypotheses, in which the SEM was used to test the research hypotheses. The researchers used SPSS software, version 27 for data analysis. Some of the aspects that were examined included the examination of outliers in the data, the examination of collinearity between the components of the research variables, the examination of the normality of the data and the examination of the correlation between the research variables using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the distribution of the research variables, and since this test was significant for the research variables (P<0.05), it was concluded that the research variables did not have a normal distribution. Therefore, SmartPLS software, version 4 was utilized. The use of SmartPLS software offers advantages over first-generation statistical software such as SPSS. SEM using this software has benefits, including the ability to implement it with three items or fewer and it can be applied even if the items do not have a normal distribution. Another advantage of this software is its capability to assess the validity and reliability of the model with multiple indicators simultaneously. Additionally, SmartPLS allows for the use of smaller samples, making it effective even when the sample size is reduced. SmartPLS software, version 4 was used to analyze the relationships between variables, with a significance level of 0.05 chosen for the analysis.

Results

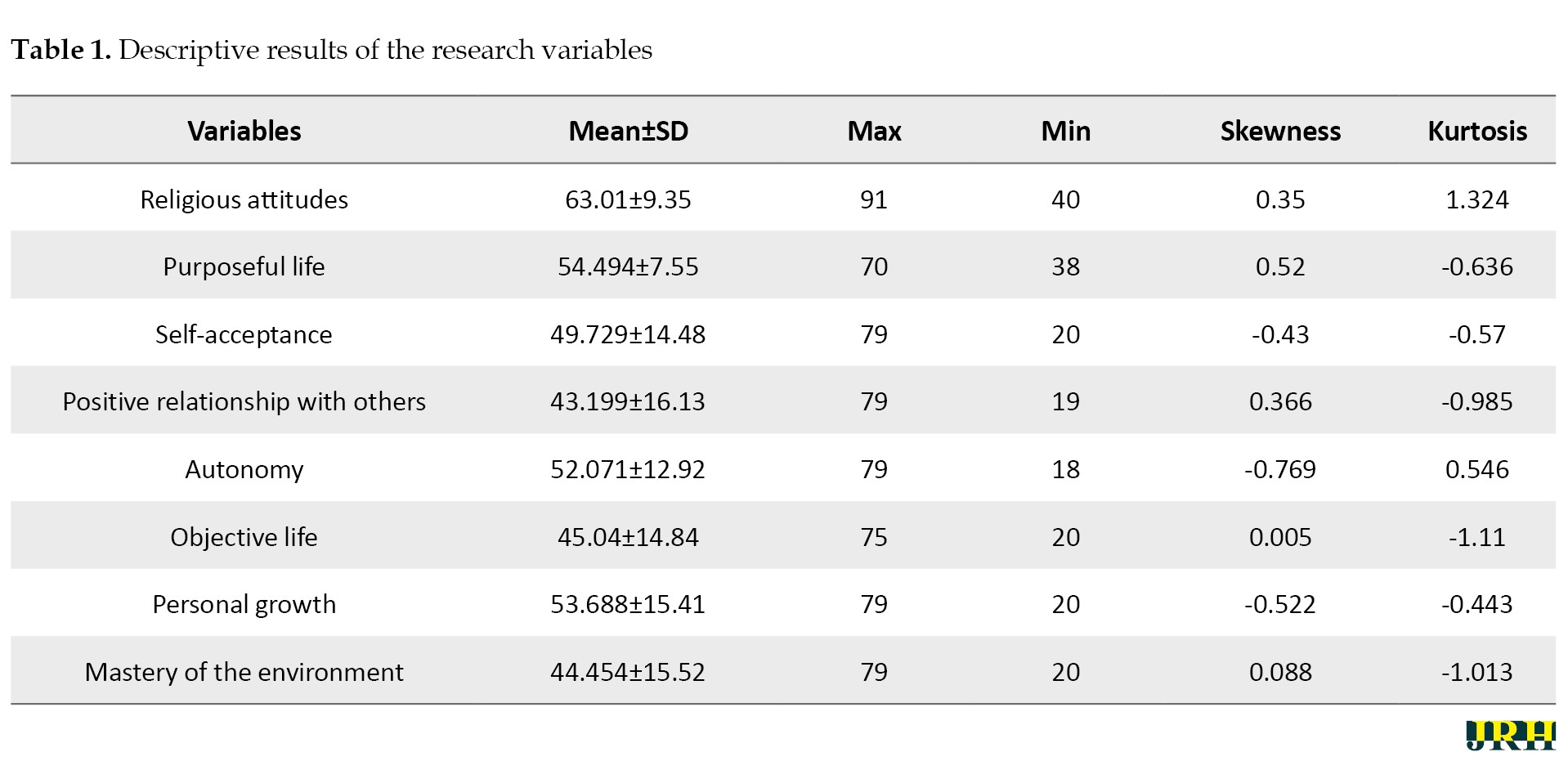

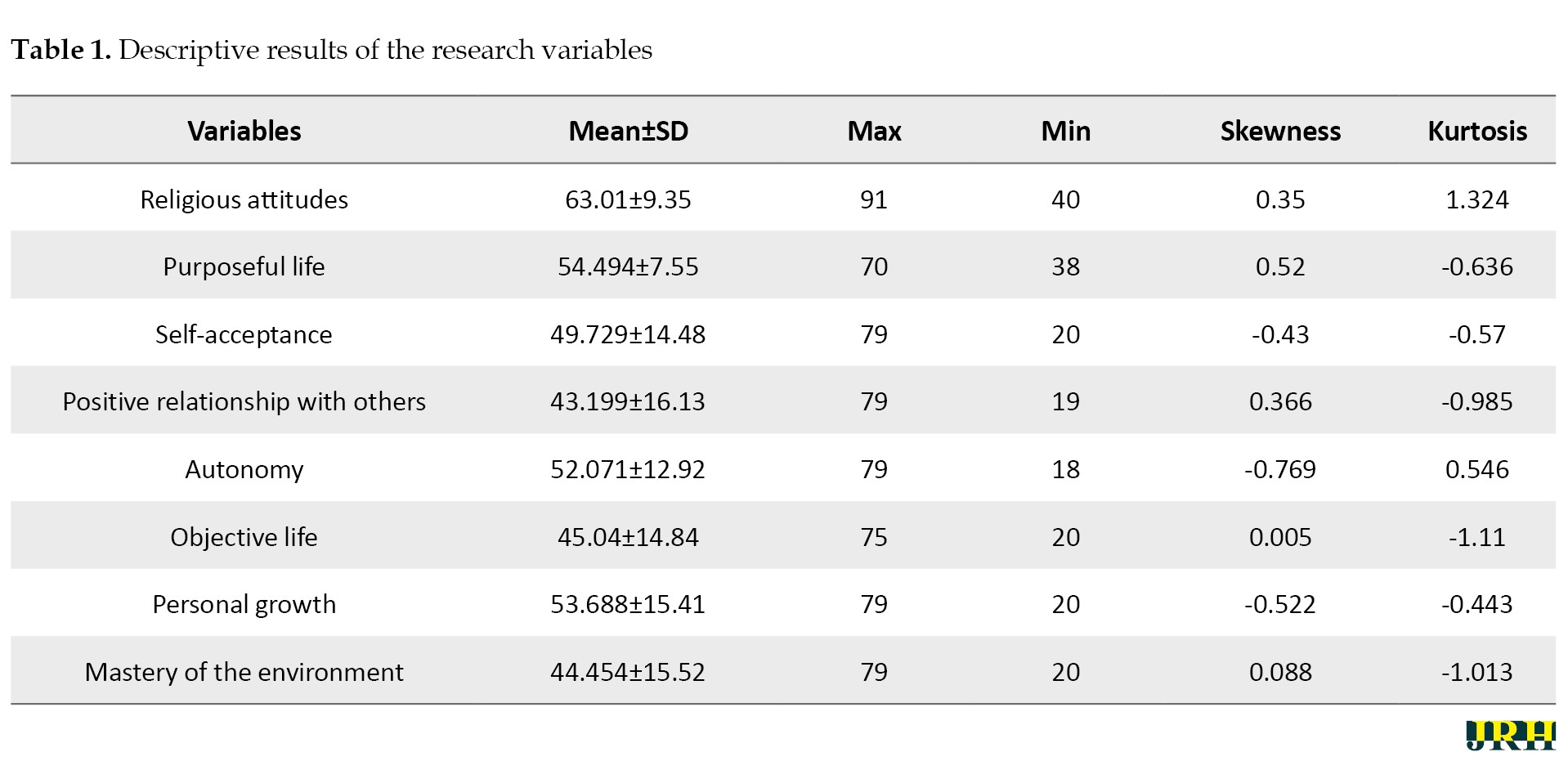

The researcher initially analyzed the descriptive statistics of the research variables. The individuals were categorized into three age groups: 15 to 16 years old (20.9%), 16 to 17 years old (26.0%) and 18 to 19 years old (53.1%). Similarly, the participants were divided into two groups based on gender, with boys comprising 60.7% and girls comprising 39.3%. Regarding self-harm, the participants were assigned into groups based on the type of self-harm, including cutting, burning skin, hitting or biting, plucking hair, engaging in physically dangerous behaviors deliberately, punching oneself or a wall, and other reasons. Table 1 shows the Mean±SD of the research variables.

In the next step, the researcher investigated the assumptions of the variables test. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the distribution of the research variables. Since this test was significant for the research variables, it was concluded that the research variables do not have a normal distribution; therefore, it is preferable to use SmartPLS software to run the SEM.

Random sample: The researcher’s sampling method was random; thus, this assumption was met.

Sufficient data: The sample size (or the size of the data set) was adequate for implementing the SEM using the partial least squares method, with a total of 196 participants.

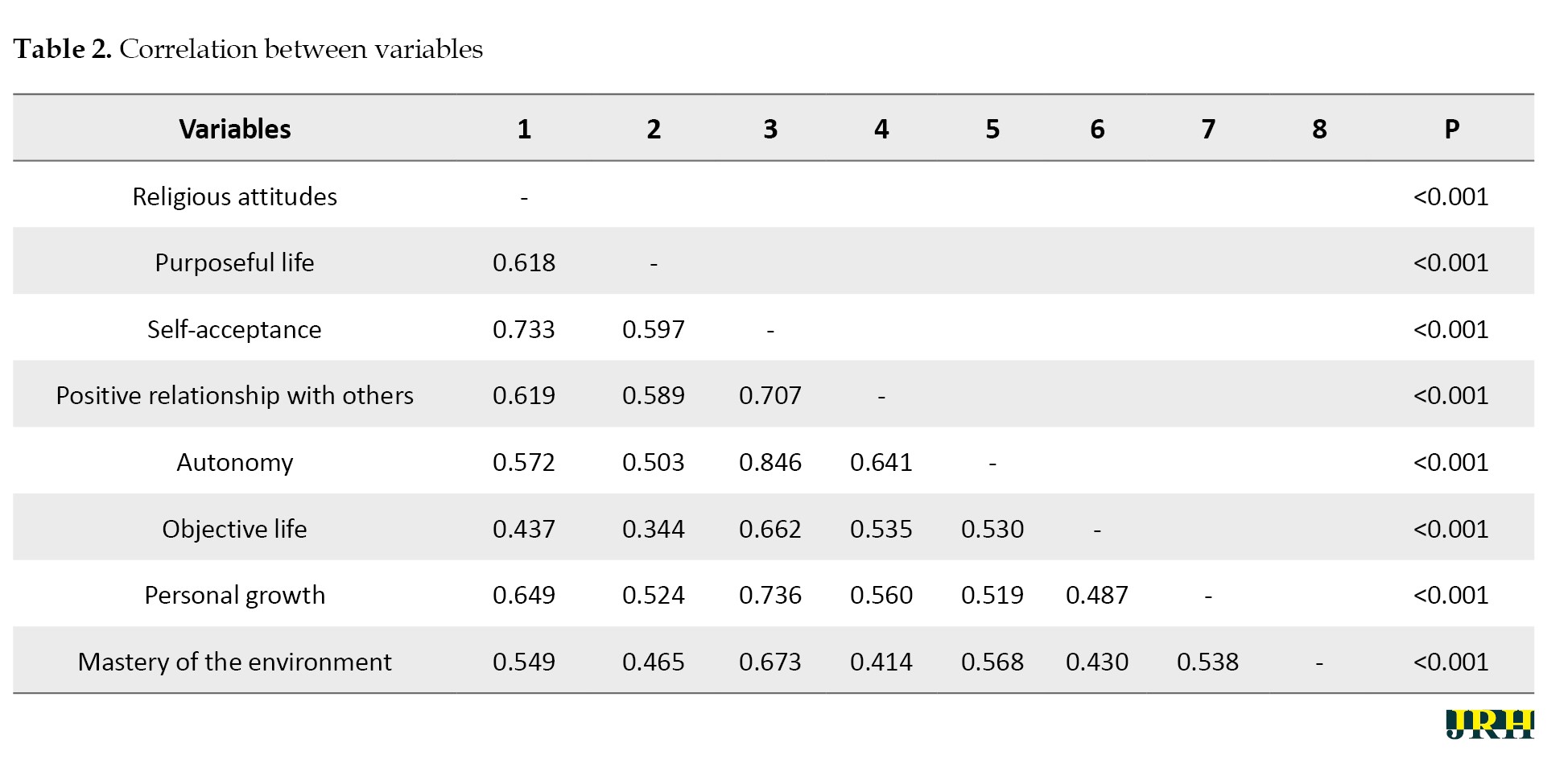

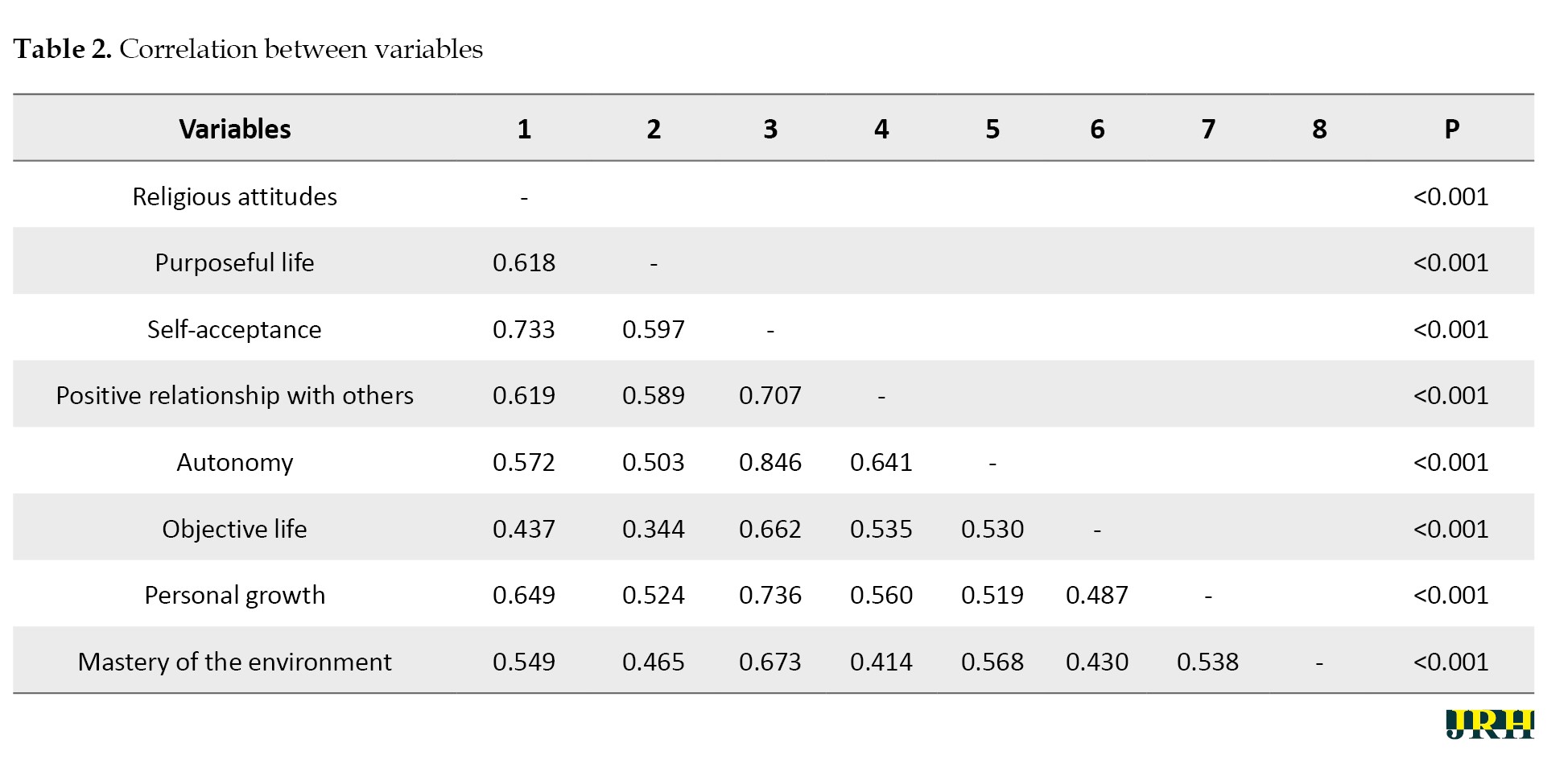

Based on the data presented in Table 2, self-acceptance, positive relationship with others, autonomy, objective life, personal growth, and mastery of the environment had a notable and favorable correlation with religious attitudes and purposeful life.

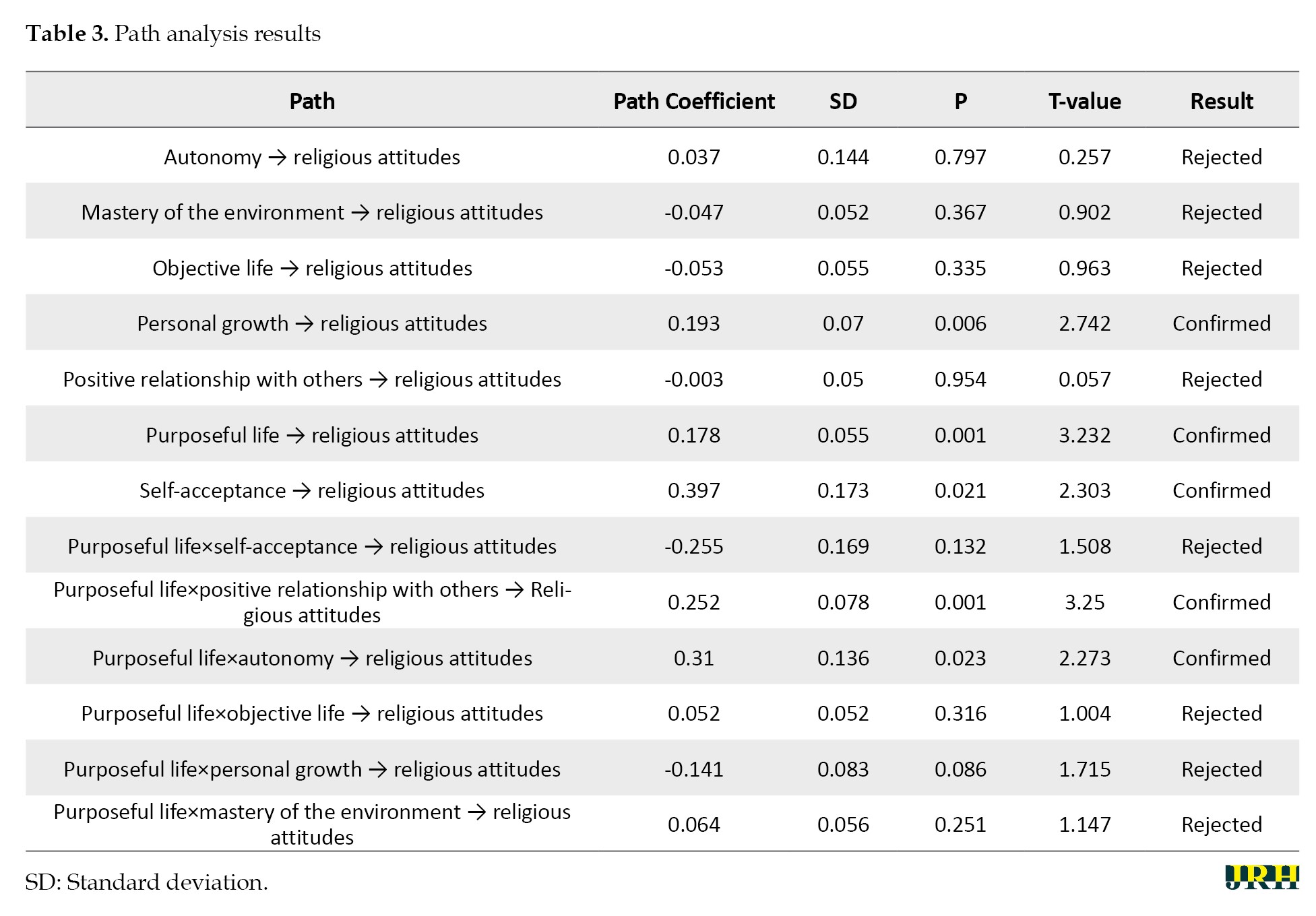

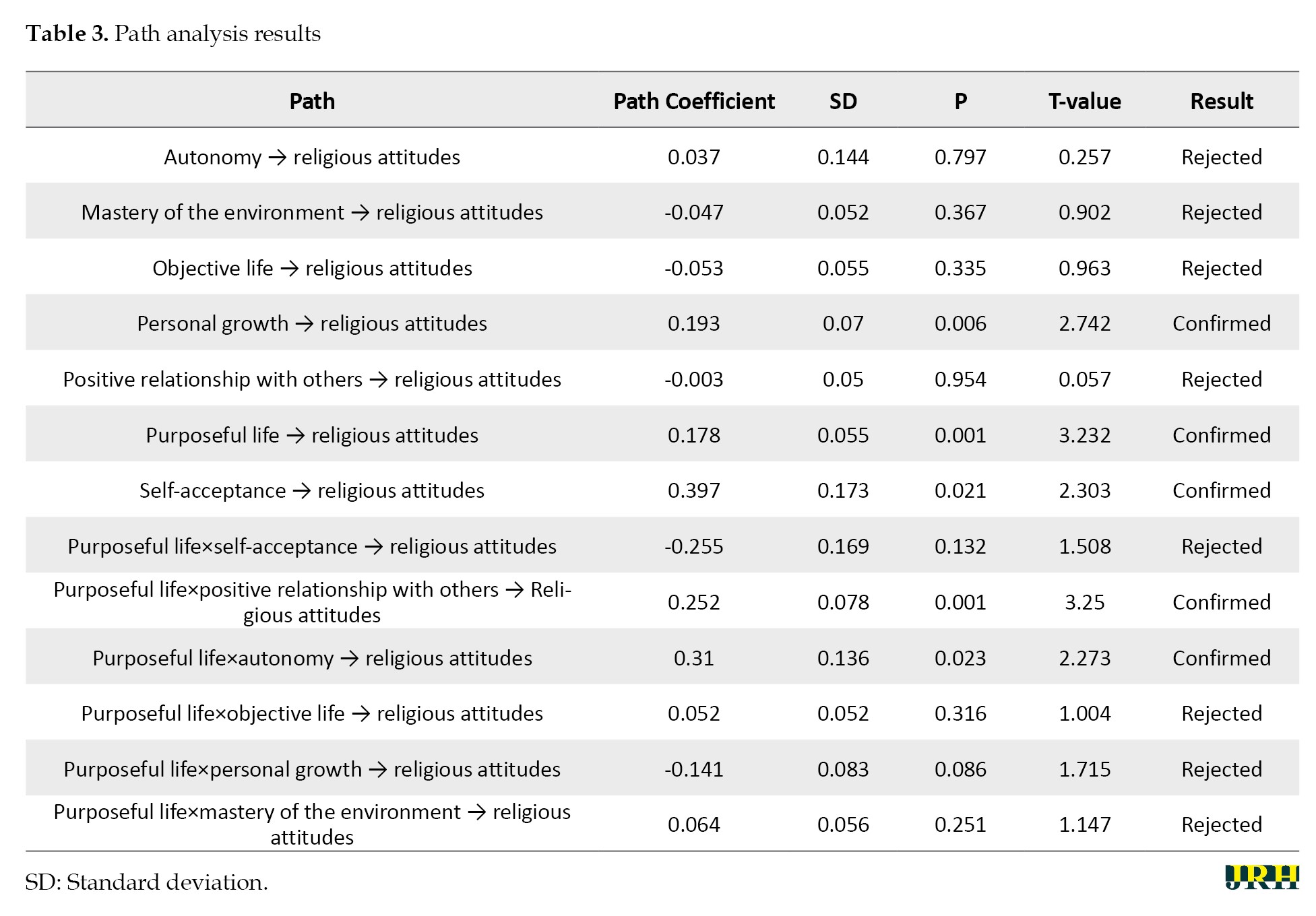

After running the model, the researcher examined the path coefficients between the research variables and the significance levels among the variables, as shown in Table 3.

In this study, the researcher set the bootstrap value to 5,000.

The findings presented in Table 3 and Figure 2 reveal that self-acceptance had a significant and positive impact on religious attitudes (β=0.397, P=0.021). However, the positive relationship with other components had no significant influence on religious attitudes (P=0.954). Similarly, the autonomy showed no significant effect on religious attitudes (P=0.797). The objective life also demonstrated no significant impact on religious attitudes (P=0.335). On the other hand, personal growth had a significant and positive effect on religious attitudes (β=0.193, P=0.006). Furthermore, mastery of the environment did not have a significant effect on religious attitudes (P=0.367). Purposeful life showed a significant and positive association with religious attitudes (β=0.178, P=0.001). Additionally, a purposeful life acted as a moderator and positively influenced the relationship between the positive relationship with others and autonomy with religious attitudes. However, purposeful life as a moderating variable did not affect the relationship between objective life and mastery of the environment, personal growth, self-acceptance, and religious attitudes (P>0.05).

Similarly, the validity of the model was also checked using the average variance extracted (AVE). Since its value for research variables was <0.5, it can be concluded that the validity of the model was confirmed. Additionally, the researcher examined the fit of the model, and all fit indices were confirmed. The standardized root mean square residual index (SRMR) represents the difference between the observed correlation and the correlation matrix of the structural model. If the value of this index is <0.08, it indicates a good fit for the model. The SRMR value for the model was equal to 0.03.

Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to predict the association between psychological well-being and religious beliefs, considering the moderating influence of life goals in self-harming adolescents. The results demonstrated that the acceptance of oneself and individual development exerted a constructive and considerable impact on religious perspectives. Moreover, the efficacy of positive social connections, independence, authority over one’s surroundings and a meaningful existence did not yield a noteworthy effect on religious beliefs. It is also important to note that life objectives have a constructive and significant impact on religious beliefs. Furthermore, life goals acted as a moderating variable, reinforcing the relationship between positive relationships with others and autonomy with religious attitudes. However, the impact of purposeful life as a moderating factor remained insignificant in relation to the connection between purposeful life, maintaining control over one’s surroundings, personal development, self-acceptance, and religious beliefs.

The results of this current study support previous research [32, 17] suggesting a strong and positive influence of self-acceptance and personal growth on religious attitudes. Previous research has indicated that engaging in religious activities can bring about feelings of peace and submission to a higher power and that combining counseling with spiritual practices is an effective means of enhancing one’s spiritual well-being, which correlates with self-acceptance [32]. Additionally, another study demonstrated a positive association between spirituality, health-related behaviors, and psychological well-being [17]. Another study was conducted to examine how religious and spiritual beliefs impact psychological well-being and burnout. The results of this study showed that religion and spirituality exert a favorable influence on one’s psychological well-being, particularly by diminishing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization while fostering success. This study emphasized the importance of personal relevance in this context [33]. Psychological well-being as a vital element in public health, is worthy of mention. It encompasses various aspects, such as subjective emotional experience, life satisfaction, psychological functioning, positive relationships, and self-fulfillment [4].

Psychological well-being encompasses various aspects of well-being, such as a positive sense of self and satisfaction with past experiences (self-acceptance), as well as a sense of personal growth and progress (personal growth) [17]. It is an essential component of our overall health. Additionally, certain adolescents possess greater resilience to negative emotions, making them less susceptible to a decline in well-being and mental health. Individuals with a strong religious orientation are also less prone to suffering damage to their psychological well-being when they encounter symptoms of emotional disorders [34]. Due to their religious perspective, the belief in God—an ever-present entity in human existence—takes precedence. Consequently, a person of faith consistently experiences the presence and guidance of God in their life, even during challenging and distressing moments. When faced with adversity and unfortunate circumstances, individuals do not perceive themselves as alone; instead, they acknowledge God as a witness and observer of their conduct. Furthermore, religion serves as a source of solace and purpose in one’s life, thus making it a significant predictor of overall health and well-being. Encounters with religious and spiritual struggles can enhance life satisfaction and alleviate anxiety by fostering spiritual growth and aiding in the search for personal meaning [18]. Additionally, adolescents with heightened spiritual and religious orientations exhibit fewer risky behaviors and possess greater psychological well-being and self-esteem [35].

Given the absence of prior research specifically examining the interconnectedness of purposeful life and religious attitudes, there is a dearth of consistent and non-conflicting research background concerning this aspect. Thus, it becomes crucial to establish and validate the alignment between the study findings and the relevant contextual backgrounds. In light of this, our results indicated that nurturing a sense of purpose could serve as a valuable target for interventions aimed at mitigating or preventing loneliness, particularly among individuals experiencing psychological distress [36]. Furthermore, Yager et al. revealed a robust correlation between a sense of purpose and both physical and mental health outcomes [37]. Additionally, adolescents with well-defined aspirations display elevated levels of life contentment, coupled with a heightened sense of significance and communal support, compared to other demographics [21]. When elucidating this finding, it is imperative to acknowledge that harboring lofty ambitions is correlated with enhanced psychosocial welfare, healthier lifestyle choices (such as elevated levels of physical activity and decreased occurrences of sleep disturbances), as well as a diminished susceptibility to various ailments (such as stroke) and mortality [38]. Purposeful life and personal growth are fundamental components of psychological well-being. Individuals who contemplate the future, possess future-oriented goals and seek meaning are more adept at dealing with challenging environmental circumstances. Those with religious inclinations assign significance to life through metaphysical beliefs, interpreting its meaning, experiencing a sense of duty and obligation through a life mission, and ultimately constructing new meanings. Spirituality, faith, and religion serve as pivotal elements in determining one’s sense of purpose and identity and provide a foundation for effectively coping with life’s changes [35].

Furthermore, in light of the findings of the current study regarding the influential role of life goals as a moderating variable in the association between positive interpersonal relationships, autonomy, and religious attitudes, as well as its lack of impact on the relationship between purposeful living, environmental mastery, personal growth and self-acceptance, research in this specific area is scarce. However, this research is indirectly in line with previous studies [39, 40]. A previous study demonstrated a positive correlation between the absence of conflicting goals and psychological well-being [39]. Additionally, another study indicated that individuals with fewer social connections, a limited number of close friends, living alone, and being unemployed are more likely to have a lower sense of purpose [40]. Having a purpose in life is crucial for humans and can bring several benefits. Increasing purpose in life can help overcome physical and mental disorders, lower mortality rates from various diseases, improve health and increase life expectancy. Individuals with a stronger sense of purpose are more likely to have self-regulation and adopt a healthy lifestyle [41]. Although there is a correlation between intentions and health-related actions, it is important to note that they do not influence all behaviors. Some individuals with ambitious goals may engage in unhealthy behaviors to cope with the pressures that arise from striving for their aspirations, especially if prioritizing health is not seen as a crucial aspect of their objective. On the other hand, some individuals may avoid unhealthy behaviors because it hinders them from achieving their overall goal, which includes maintaining good health, such as graduating from college [38]. Pursuing personal goals can lead to a fulfilling life by providing meaning and structure to one’s activities and identity. In addition, setting meaningful goals can help improve the psychological well-being of adolescents who harm themselves [39].

Every research design has specific constraints, and the accuracy of interpreting the findings should be acknowledged considering these limitations. The present study has certain limitations, including the inability to investigate all the factors that influence psychological well-being. For future research, it is recommended to consider factors, such as educational status and cultural, social, economic, and scientific level of adolescents with self-injury. Additionally, the study’s limitations include a small sample size and a limited population, which restricts the generalizability of the results. Therefore, future research should aim to include a larger sample size. Another significant limitation of this study was the lack of information on the impact of life goals on religious attitudes and well-being components. It is suggested that more researchers address this issue in future studies. Moreover, despite assuring participants of strict confidentiality, the sensitive nature of self-harm among adolescents resulted in opposition and reluctance from some adolescents, particularly their parents. It is recommended that future research investigate the role of the family along with factors such as purpose and mental well-being in adolescents who self-injure and that the results be compared with those of the current research to obtain more comprehensive information in this field.

Conclusion

The study found that psychological well-being and purposeful life contribute to religious attitudes in self-harming adolescents. Only self-acceptance and personal growth had a positive impact on religious attitudes. Other factors, such as positive relationships, autonomy, mastery, and purposeful life did not affect religious attitudes. Purpose in life strengthened the relationship between positive relationships and autonomy with religious attitudes. However, it did not affect the relationship between purpose in life and mastering the environment, personal growth and self-acceptance with religious attitudes. Considering the importance of adolescence and the possibility of self-harming behaviors due to mental and physical injuries in teenagers during this sensitive period, investigating the factors that reduce self-harm in this population is a very important and necessary task. Addressing these injuries can be a significant step toward moving towards a healthy society. Future studies should focus on the evolution of psychological well-being indicators, the relationship between objective and mental indicators among young people, factors related to psychological well-being, and the analysis of psychological well-being in different social groups.

To enhance knowledge about the factors influencing mental well-being in teenagers, particularly those who engage in self-harm, further research is deemed essential for future advancements in mental health literature. Professionals dealing with teenagers, such as family therapists, counselors and psychologists should acknowledge the critical role of mental health in teenagers. Educators have the potential to positively impact teenagers’ growth and well-being by promoting these factors, leading to a reduction in self-harm behaviors among teenagers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the West Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.WT.REC.1402.159). The authors fully adhered to ethical considerations, which encompass plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, and other related issues.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all those who took part in this study.

References

Self-harm has emerged as a significant global public health issue, impacting approximately one million individuals worldwide. Among adolescents, the prevalence of self-harm ranges from 10 to 20% throughout their lifetime. Furthermore, self-harm tends to initiate and reach its peak during adolescence [1]. It has been defined as deliberate self-poisoning or injury regardless of the apparent motivation behind the act. This behavior is closely linked to an increased likelihood of future suicide [2]. Despite being classified as a high-risk group, it is crucial to identify the factors associated with a reduced risk of self-harm among young people and gain insights into why this is the case. Understanding and addressing these aspects are essential in the prevention of self-harm within this population [3].

Hence, self-harm behaviors, in terms of reduced feelings of defeat and internal entrapment, were indirectly associated with psychological well-being [4]. Psychological well-being, which encompasses positive feelings, thoughts, and strategies, has been linked to better physical health and longer lifespan. Better physical health and longer lifespan have been associated with psychological well-being, which entails positive emotions, thoughts, and coping mechanisms [5]. A person with psychological well-being must have the following six characteristics: Self-acceptance and self-peace, positive relationships with others, self-thinking and behavior, mastering the environment, having a purpose and meaning in life, and evaluating life as a learning and development process [6]. Recognizing its impact on public health, promoting psychological well-being in adolescents is now a global priority [7]. It is plausible that greater psychological well-being can shield adolescent individuals from intentional self-harm and self-poisoning by decreasing feelings of defeat and entrapment and acting as a buffer against the development of self-harming intentions [8]. Stopping self-harm is associated with better psychological well-being and higher role functioning [9].

Adolescents who have engaged in self-harm in the past were found to have a higher likelihood of reporting lower levels of psychological well-being [10, 11]. There is a theoretical model that explains why religious adolescents display less risky behavior compared to nonreligious adolescents, consisting of four mechanisms. These mechanisms include the influence of religion on the availability of opportunities for engaging in risky behavior, the appeal of risky behavior, the moral acceptability of risky behavior, and the ability to exercise self-control over impulses. While these mechanisms are not exclusive to religions, our model identifies three aspects of religion that can foster them [12].

Religious attitude comprises four aspects of religiosity: Belief, personal experiences, consequences, and rituals. These aspects can have a significant emotional and psychological influence on individuals, particularly adolescents, ultimately leading to increased self-confidence and mental well-being [13]. A study has presented evidence supporting the protective effect of certain religious practices on self-harm and suicidal behaviors in adolescents [14]. Other studies have also highlighted the significant role of preventive education focused on religiosity and moral foundations in reducing risky behaviors, particularly in teenage girls struggling with addiction [15]. Grover et al. demonstrated that individuals who engage in self-harm have a lower tendency to use positive religious coping strategies and a higher tendency to employ negative religious coping strategies [16]. In addition, both spirituality and health-related behaviors have a positive relationship with psychological well-being [17].

Religion can establish a belief system that encompasses finding meaning in life, experiencing a positive sense of self, and recognizing one’s deservingness of respect [18]. Encouraging young individuals to discover a purpose in life contributes to their positive development [19]. Heng et al. found that nearly all adolescents believed that having a purpose provides a foundation and direction in life, and more than half mentioned that it leads to increased happiness [20]. Furthermore, prominent scholars have proposed theories suggesting that a sense of purpose in life may be especially common among highly talented adolescents [21]. Bronk et al. indicated that high-ability early and late adolescents demonstrated a similar prevalence of purpose compared to their peers with more typical abilities. However, high-ability youth reported adopting self-centered life goals more than their peers and identified different inspiring life purposes [22]. Also, the goal in life mediates the relationship between religious attitude and mental well-being [23].

Due to the special period of their development, teenagers have to face many biological, academic and social transitional events that may force them to perform risky behaviors, such as self-harm. Since these behaviors are associated with many harms to individuals and society and may become contagious among adolescents, it is necessary to address the factors that can help this group of adolescents. Despite the significance of this topic, there have been limited studies conducted in this particular field and none have explored the correlation between the psychological well-being and religious attitudes of self-harming adolescents in relation to their life purposes. Consequently, a research gap exists and this study offers a new perspective. Accordingly, this research aimed to investigate the relationship between psychological well-being and religious attitudes while considering the mediating role of life purposes among self-harming adolescents. Figure 1 illustrates the researcher’s conceptual model for this study.

Methods

Research design

This descriptive-correlational utilized the cross-sectional approach along with structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population comprised all adolescents, both male and female, who had engaged in self-harm behaviors in Tehran from July to October 2023. The presence of these behaviors was verified by expert psychologists at research clinics.

Sample and sampling method

The research involved 250 adolescents who had previously participated in self-harm activities and were selected using purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling method, in which based on specific assumptions, qualified people (teenagers with self-harm) are selected as a sample. Since the current research was conducted on a specific group of teenagers, the sampling method should have been chosen purposefully. Therefore, the necessary characteristics for selecting individuals as samples were first identified. Then, eligible teenagers were selected. Among the limitations of this method that may introduce bias, the purposeful sampling method for data collection is particularly susceptible to research bias. If chosen incorrectly, the sample size may not be representative of the population. However, to avoid bias in the sample size, the researcher carefully established the entry and exit criteria.

The suitability of the sample size was determined using the formulas provided by Cohen [24] and Westland [25] for estimating the required sample size in SEM studies. The decision considered the amount of variables observed and latent variables in the model, the anticipated impact size, and the intended probability and statistical power. The following values were used to calculate the sample size: Effect size: 0.3, statistical power level: 0.8, latent variables: 3, observed variables: 129, and probability level: 0.01. Through this calculation, the researcher determined that the sample size would be 161 people. However, due to the risk of a significant reduction in the research sample, the researcher decided to aim for a sample size of 200 individuals to prevent attrition.

The requirements for participation in the study encompassed having a documented psychological history of self-harm behavior, providing informed consent, receiving consent from the parents of the adolescents, and possessing adequate literacy and comprehension skills to respond to the inquiries. To be eligible for participation, participants had to be over 19 years old and free from any physical or mental conditions that hindered their ability to respond. Additionally, failing to answer more than eight questions resulted in withdrawal from the study. Initially, the researchers obtained the required permissions from their university to conduct the study. Subsequently, with the assistance of university professors, the researchers were connected to ten psychology and counseling clinics in Tehran.

The purpose of reserving the clinics’ names was to safeguard the information. These specific clinics were selected based on their seamless coordination and execution of research, as well as the potential for collaboration in engaging with youths displaying self-harming behaviors. Subsequently, the researcher visited the clinics and collaborated with their management department to carry out the research project. Then, a message was dispatched to the families who had a child with a previous self-harm history and had utilized counseling and treatment services at the research clinics, inviting them to participate in the study. The next step involved sending more comprehensive information about the study to the participants through social media platforms. This information included the objectives of the research, the necessary permits, and guidelines regarding adherence to ethical principles. Participants were informed that none of the research materials contained their personal information and that adolescents could withdraw from the study at any time if they wished to do so. The research process and completion of online questionnaires took three months. A total of 196 out of 200 questionnaires were used for analysis, while four questionnaires were excluded for being incomplete or intentionally erroneous. Participants filled out the questionnaires themselves online. To comply with ethical principles, a consent form indicating their willingness to participate was obtained from the participants before administering the questionnaires. They were informed that participation in the research was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. It was also explained to them that these tests did not contain any identifying information.

Tools

Ryff’s psychological well-being scales (PWB)

This 84-question self-assessment questionnaire was developed by Ryff in 1980 to measure psychological well-being [26]. It has six factors, including self-acceptance, positive relationship with others, autonomy, purposeful life, personal growth and mastering the environment, each containing 14 questions. The questionnaire utilizes a six-point Likert scale, ranging from one (completely disagree) to five (completely agree), and the component scores range from 14 to 86. Ryff [26] reported that Cronbach’s α coefficients for the scale components are as follows: Self-acceptance is equal to 0.93, positive relationships with others are equal to 0.91, autonomy is equal to 0.86, objective life is equal to 0.90, personal growth is equal to 0.90 and mastery of the environment obtained a value of 0.87. Iranian researchers have documented that the scale’s internal consistency ranges between 0.76 and 0.83 [27]. This research found that the self-acceptance dimension had a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.893, while the positive relationship with others had a coefficient of 0.774. Autonomy had a coefficient of 0.807, objective life had a coefficient of 0.782, personal growth had a coefficient of 0.749 and mastery of the environment had a coefficient of 0.749. Moreover, the Cronbach α coefficient of the whole scale was determined to be 0.631.

Religious attitude questionnaire (RAQ)

This questionnaire is a 25-question self-assessment scale designed by Sadeghi et al to measure religious attitudes [28]. This questionnaire is scored on a five-point Likert scale (zero to four) and the range of scores is from 0 to 100. A score of 76 to 100 is classified as excellent religious attitude, 51 to 75 as good, 26 to 50 as average, and 25 as low as weak religious attitude. The reliability of the scale was determined using the correlation method and was found to be 0.80, which was confirmed by the manufacturer of the scale. The scale’s internal consistency was examined by researchers in Iran, who determined its reliability using Cronbach’s α with a value of 0.67 [29]. In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.831.

Purpose-in-life questionnaire (PIL)

The PIL, consisting of 20 questions, was developed and revised by Maholick and Crumbaugh in 1969. The main objective of this questionnaire is to assess an individual’s perception and significance of their purpose or meaning in life [30]. The scale has a minimum score of 20 and a maximum score of 100. If a person’s score is <50, it indicates aimlessness in life; conversely, if the score is higher than 50, it suggests that the person has a clear goal in life. Iranian researchers have reported that the scale’s internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.92 [31]. In this research, the researcher found the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale to be 0.899.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD were used to describe the data and the results were reported as frequency distribution tables. The second part included the analysis of the research hypotheses, in which the SEM was used to test the research hypotheses. The researchers used SPSS software, version 27 for data analysis. Some of the aspects that were examined included the examination of outliers in the data, the examination of collinearity between the components of the research variables, the examination of the normality of the data and the examination of the correlation between the research variables using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the distribution of the research variables, and since this test was significant for the research variables (P<0.05), it was concluded that the research variables did not have a normal distribution. Therefore, SmartPLS software, version 4 was utilized. The use of SmartPLS software offers advantages over first-generation statistical software such as SPSS. SEM using this software has benefits, including the ability to implement it with three items or fewer and it can be applied even if the items do not have a normal distribution. Another advantage of this software is its capability to assess the validity and reliability of the model with multiple indicators simultaneously. Additionally, SmartPLS allows for the use of smaller samples, making it effective even when the sample size is reduced. SmartPLS software, version 4 was used to analyze the relationships between variables, with a significance level of 0.05 chosen for the analysis.

Results

The researcher initially analyzed the descriptive statistics of the research variables. The individuals were categorized into three age groups: 15 to 16 years old (20.9%), 16 to 17 years old (26.0%) and 18 to 19 years old (53.1%). Similarly, the participants were divided into two groups based on gender, with boys comprising 60.7% and girls comprising 39.3%. Regarding self-harm, the participants were assigned into groups based on the type of self-harm, including cutting, burning skin, hitting or biting, plucking hair, engaging in physically dangerous behaviors deliberately, punching oneself or a wall, and other reasons. Table 1 shows the Mean±SD of the research variables.

In the next step, the researcher investigated the assumptions of the variables test. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the distribution of the research variables. Since this test was significant for the research variables, it was concluded that the research variables do not have a normal distribution; therefore, it is preferable to use SmartPLS software to run the SEM.

Random sample: The researcher’s sampling method was random; thus, this assumption was met.

Sufficient data: The sample size (or the size of the data set) was adequate for implementing the SEM using the partial least squares method, with a total of 196 participants.

Based on the data presented in Table 2, self-acceptance, positive relationship with others, autonomy, objective life, personal growth, and mastery of the environment had a notable and favorable correlation with religious attitudes and purposeful life.

After running the model, the researcher examined the path coefficients between the research variables and the significance levels among the variables, as shown in Table 3.

In this study, the researcher set the bootstrap value to 5,000.

The findings presented in Table 3 and Figure 2 reveal that self-acceptance had a significant and positive impact on religious attitudes (β=0.397, P=0.021). However, the positive relationship with other components had no significant influence on religious attitudes (P=0.954). Similarly, the autonomy showed no significant effect on religious attitudes (P=0.797). The objective life also demonstrated no significant impact on religious attitudes (P=0.335). On the other hand, personal growth had a significant and positive effect on religious attitudes (β=0.193, P=0.006). Furthermore, mastery of the environment did not have a significant effect on religious attitudes (P=0.367). Purposeful life showed a significant and positive association with religious attitudes (β=0.178, P=0.001). Additionally, a purposeful life acted as a moderator and positively influenced the relationship between the positive relationship with others and autonomy with religious attitudes. However, purposeful life as a moderating variable did not affect the relationship between objective life and mastery of the environment, personal growth, self-acceptance, and religious attitudes (P>0.05).

Similarly, the validity of the model was also checked using the average variance extracted (AVE). Since its value for research variables was <0.5, it can be concluded that the validity of the model was confirmed. Additionally, the researcher examined the fit of the model, and all fit indices were confirmed. The standardized root mean square residual index (SRMR) represents the difference between the observed correlation and the correlation matrix of the structural model. If the value of this index is <0.08, it indicates a good fit for the model. The SRMR value for the model was equal to 0.03.

Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to predict the association between psychological well-being and religious beliefs, considering the moderating influence of life goals in self-harming adolescents. The results demonstrated that the acceptance of oneself and individual development exerted a constructive and considerable impact on religious perspectives. Moreover, the efficacy of positive social connections, independence, authority over one’s surroundings and a meaningful existence did not yield a noteworthy effect on religious beliefs. It is also important to note that life objectives have a constructive and significant impact on religious beliefs. Furthermore, life goals acted as a moderating variable, reinforcing the relationship between positive relationships with others and autonomy with religious attitudes. However, the impact of purposeful life as a moderating factor remained insignificant in relation to the connection between purposeful life, maintaining control over one’s surroundings, personal development, self-acceptance, and religious beliefs.

The results of this current study support previous research [32, 17] suggesting a strong and positive influence of self-acceptance and personal growth on religious attitudes. Previous research has indicated that engaging in religious activities can bring about feelings of peace and submission to a higher power and that combining counseling with spiritual practices is an effective means of enhancing one’s spiritual well-being, which correlates with self-acceptance [32]. Additionally, another study demonstrated a positive association between spirituality, health-related behaviors, and psychological well-being [17]. Another study was conducted to examine how religious and spiritual beliefs impact psychological well-being and burnout. The results of this study showed that religion and spirituality exert a favorable influence on one’s psychological well-being, particularly by diminishing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization while fostering success. This study emphasized the importance of personal relevance in this context [33]. Psychological well-being as a vital element in public health, is worthy of mention. It encompasses various aspects, such as subjective emotional experience, life satisfaction, psychological functioning, positive relationships, and self-fulfillment [4].

Psychological well-being encompasses various aspects of well-being, such as a positive sense of self and satisfaction with past experiences (self-acceptance), as well as a sense of personal growth and progress (personal growth) [17]. It is an essential component of our overall health. Additionally, certain adolescents possess greater resilience to negative emotions, making them less susceptible to a decline in well-being and mental health. Individuals with a strong religious orientation are also less prone to suffering damage to their psychological well-being when they encounter symptoms of emotional disorders [34]. Due to their religious perspective, the belief in God—an ever-present entity in human existence—takes precedence. Consequently, a person of faith consistently experiences the presence and guidance of God in their life, even during challenging and distressing moments. When faced with adversity and unfortunate circumstances, individuals do not perceive themselves as alone; instead, they acknowledge God as a witness and observer of their conduct. Furthermore, religion serves as a source of solace and purpose in one’s life, thus making it a significant predictor of overall health and well-being. Encounters with religious and spiritual struggles can enhance life satisfaction and alleviate anxiety by fostering spiritual growth and aiding in the search for personal meaning [18]. Additionally, adolescents with heightened spiritual and religious orientations exhibit fewer risky behaviors and possess greater psychological well-being and self-esteem [35].

Given the absence of prior research specifically examining the interconnectedness of purposeful life and religious attitudes, there is a dearth of consistent and non-conflicting research background concerning this aspect. Thus, it becomes crucial to establish and validate the alignment between the study findings and the relevant contextual backgrounds. In light of this, our results indicated that nurturing a sense of purpose could serve as a valuable target for interventions aimed at mitigating or preventing loneliness, particularly among individuals experiencing psychological distress [36]. Furthermore, Yager et al. revealed a robust correlation between a sense of purpose and both physical and mental health outcomes [37]. Additionally, adolescents with well-defined aspirations display elevated levels of life contentment, coupled with a heightened sense of significance and communal support, compared to other demographics [21]. When elucidating this finding, it is imperative to acknowledge that harboring lofty ambitions is correlated with enhanced psychosocial welfare, healthier lifestyle choices (such as elevated levels of physical activity and decreased occurrences of sleep disturbances), as well as a diminished susceptibility to various ailments (such as stroke) and mortality [38]. Purposeful life and personal growth are fundamental components of psychological well-being. Individuals who contemplate the future, possess future-oriented goals and seek meaning are more adept at dealing with challenging environmental circumstances. Those with religious inclinations assign significance to life through metaphysical beliefs, interpreting its meaning, experiencing a sense of duty and obligation through a life mission, and ultimately constructing new meanings. Spirituality, faith, and religion serve as pivotal elements in determining one’s sense of purpose and identity and provide a foundation for effectively coping with life’s changes [35].

Furthermore, in light of the findings of the current study regarding the influential role of life goals as a moderating variable in the association between positive interpersonal relationships, autonomy, and religious attitudes, as well as its lack of impact on the relationship between purposeful living, environmental mastery, personal growth and self-acceptance, research in this specific area is scarce. However, this research is indirectly in line with previous studies [39, 40]. A previous study demonstrated a positive correlation between the absence of conflicting goals and psychological well-being [39]. Additionally, another study indicated that individuals with fewer social connections, a limited number of close friends, living alone, and being unemployed are more likely to have a lower sense of purpose [40]. Having a purpose in life is crucial for humans and can bring several benefits. Increasing purpose in life can help overcome physical and mental disorders, lower mortality rates from various diseases, improve health and increase life expectancy. Individuals with a stronger sense of purpose are more likely to have self-regulation and adopt a healthy lifestyle [41]. Although there is a correlation between intentions and health-related actions, it is important to note that they do not influence all behaviors. Some individuals with ambitious goals may engage in unhealthy behaviors to cope with the pressures that arise from striving for their aspirations, especially if prioritizing health is not seen as a crucial aspect of their objective. On the other hand, some individuals may avoid unhealthy behaviors because it hinders them from achieving their overall goal, which includes maintaining good health, such as graduating from college [38]. Pursuing personal goals can lead to a fulfilling life by providing meaning and structure to one’s activities and identity. In addition, setting meaningful goals can help improve the psychological well-being of adolescents who harm themselves [39].

Every research design has specific constraints, and the accuracy of interpreting the findings should be acknowledged considering these limitations. The present study has certain limitations, including the inability to investigate all the factors that influence psychological well-being. For future research, it is recommended to consider factors, such as educational status and cultural, social, economic, and scientific level of adolescents with self-injury. Additionally, the study’s limitations include a small sample size and a limited population, which restricts the generalizability of the results. Therefore, future research should aim to include a larger sample size. Another significant limitation of this study was the lack of information on the impact of life goals on religious attitudes and well-being components. It is suggested that more researchers address this issue in future studies. Moreover, despite assuring participants of strict confidentiality, the sensitive nature of self-harm among adolescents resulted in opposition and reluctance from some adolescents, particularly their parents. It is recommended that future research investigate the role of the family along with factors such as purpose and mental well-being in adolescents who self-injure and that the results be compared with those of the current research to obtain more comprehensive information in this field.

Conclusion

The study found that psychological well-being and purposeful life contribute to religious attitudes in self-harming adolescents. Only self-acceptance and personal growth had a positive impact on religious attitudes. Other factors, such as positive relationships, autonomy, mastery, and purposeful life did not affect religious attitudes. Purpose in life strengthened the relationship between positive relationships and autonomy with religious attitudes. However, it did not affect the relationship between purpose in life and mastering the environment, personal growth and self-acceptance with religious attitudes. Considering the importance of adolescence and the possibility of self-harming behaviors due to mental and physical injuries in teenagers during this sensitive period, investigating the factors that reduce self-harm in this population is a very important and necessary task. Addressing these injuries can be a significant step toward moving towards a healthy society. Future studies should focus on the evolution of psychological well-being indicators, the relationship between objective and mental indicators among young people, factors related to psychological well-being, and the analysis of psychological well-being in different social groups.

To enhance knowledge about the factors influencing mental well-being in teenagers, particularly those who engage in self-harm, further research is deemed essential for future advancements in mental health literature. Professionals dealing with teenagers, such as family therapists, counselors and psychologists should acknowledge the critical role of mental health in teenagers. Educators have the potential to positively impact teenagers’ growth and well-being by promoting these factors, leading to a reduction in self-harm behaviors among teenagers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the West Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.WT.REC.1402.159). The authors fully adhered to ethical considerations, which encompass plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, and other related issues.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all those who took part in this study.

References

- Damavandian A, Golshani F, Saffarinia M, Baghdasarians A. [Comparing the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy (CFT) and dialectic behavior therapy (DBT) on aggression, self-harm behaviors and emotional self-regulation in Juvenile offenders of Tehran Juvenile correction and rehabilitation center (Persian)]. Social Psychology Research. 2021; 11(41):31-58. [DOI:10.22034/spr.2021.253334.1579]

- Paterson A, Elliott MA, Nicholls LAB, Rasmussen S. Evidence that implementation intentions reduce self-harm in the community. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2023; 28(4):1241-60. [DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12682] [PMID]

- Jia Yun L, Motevalli S, Abu Talib M, Gholampour Garmjani M. Resilience, loneliness, and impulsivity among adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Iranian Journal of Educational Sociology. 2023; 6(4):172-87. [DOI:10.61186/ijes.6.4.1]

- McAneney H, Tully MA, Hunter RF, Kouvonen A, Veal P, Stevenson M, et al. Individual factors and perceived community characteristics in relation to mental health and mental well-being. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15:1237. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-015-2590-8] [PMID]

- Rajaei S, Sadrposhan N. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based compassion therapy on psychological well-being and life expectancy in female with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Education and Cognitive Sciences. 2022; 3(1):1-10. [DOI:10.22034/injoeas.2022.160676]

- Jelodari A, Kord Azizpour Mohamamdi R. The relationship between the personality traits and self-compassion with psychological well-being in Iranian college students: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Education and Cognitive Sciences. 2023; 4(3):20-8. [DOI:10.61838/kman.ijecs.4.3.2]

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo F, Saeidi Rezvani T, Jami R, Seadatee Shamir A. Psycho-social well-being in female students: The role of perceived parental autonomy support and warmth. Iranian Journal of Educational Sociology. 2020; 3(3):1-8. [DOI:10.52547/ijes.3.3.1]

- Bucchianeri MM, Eisenberg ME, Wall MM, Piran N, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multiple types of harassment: Associations with emotional well-being and unhealthy behaviors in adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014; 54(6):724-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.205] [PMID]

- Halpin SA, Duffy NM. Predictors of non-suicidal self-injury cessation in adults who self-injured during adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2020; 1:100017. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100017]

- Morey Y, Mellon D, Dailami N, Verne J, Tapp A. Adolescent self-harm in the community: An update on prevalence using a self-report survey of adolescents aged 13-18 in England. Journal of Public Health. 2017; 39(1):58-64. [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdw010] [PMID]

- Russell K, Rasmussen S, Hunter SC. Does mental well-being protect against self-harm thoughts and behaviors during adolescence? A six-month prospective investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6771. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17186771] [PMID]

- Shepperd JA, Forsyth RB. How does religion deter adolescent risk behavior? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2023; 32(4):337-42. [DOI:10.09637214231164404]

- Karimi N, Mousavi S, Falah-Neudehi M. [The prediction of psychological well-being based on the components of religious attitude and self-esteem among the elderly in Ahvaz, Iran (Persian)]. Journal of Pizhūhish Dar Dīn va Salāmat. 2021; 6(4):88-100. [Link]

- Malkosh-Tshopp E, Ratzon R, Gizunterman A, Levy T, Ben-Dor DH, Krivoy A, et al. The association of non-suicidal self-injurious and suicidal behaviors with religiosity in hospitalized Jewish adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2020; 25(4):801-15. [DOI:10.1177/1359104520918354] [PMID]

- Koletić G, Jurković L, Tafro A, Milas G, Landripet I, Štulhofer A. A meta-analytic exploration of associations between religious service attendance and sexual risk taking in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Journal of Health Psychology. 2023; 28(12):1103-16. [DOI:10.1177/13591053231164542] [PMID]

- Grover S, Sarkar S, Bhalla A, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A. Religious coping among self-harm attempters brought to emergency setting in India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016; 23:78-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2016.07.009] [PMID]

- Cheraghi M, Oreyzi SS, Faraahani HA. [Reliability, validity, factor analysis and normalization of the Crumbaugh and Maholick’s questionnaire of purpose-in-life (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology. 2008; 12(4):396-413. [Link]

- Dehghani F, Seifi M, Nateghi F, Faghihi A. The effectiveness of happiness training on improving the quality of life of women in Pars special economic zone staffs based on their religious attitudes. Iranian Journal of Educational Sociology. 2018; 1(9):48-59. [Link]

- Damon W, Menon J, Bronk KC. The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science. 7(3):119-28. [DOI:10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2]

- Heng MA, Fulmer GW, Blau I, Pereira A. Youth purpose, meaning in life, social support and life satisfaction among adolescents in Singapore and Israel. Journal of Educational Change. 2020; 21(2):299-322. [DOI:10.1007/s10833-020-09381-4]

- Blau I, Goldberg S, Benolol N. Purpose and life satisfaction during adolescence: the role of meaning in life, social support, and problematic digital use. Journal of Youth Studies. 2019; 22(7):907-25. [DOI:10.1080/13676261.2018.1551614]

- Bronk KC, Holmes Finch W, Talib TL. Purpose in life among high ability adolescents. High Ability Studies. 2010; 21(2):133-45. [DOI:10.1080/13598139.2010.525339]

- Aghababaei N, Sohrabi F, Eskandari H, Borjali A, Farrokhi N, Chen ZJ. Predicting subjective well-being by religious and scientific attitudes with hope, purpose in life, and death anxiety as mediators. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016; 90:93-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.046]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2013. [DOI:10.4324/9780203771587]

- Westland JC. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 2010; 9(6):476-87. [DOI:10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989; 57(6):1069. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069]

- Farzan Azar F, Mehrabi F. [The effect of reality therapy counseling on the psychological well-being of infertile women (Persian)]. Complementary Medicine Journal. 2023; 13(3):21-9. [DOI:10.61186/cmja.13.3.21]

- Sadeghi MR, Bagherzadeh Ladari R, Haghshenas MR. [A study of religious attitude and mental health in students of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2010; 20(75):71-5. [Link]

- Abbasi M, Adavi H, Hojati M. [Relationship between religious beliefs and psychological health through purposefulness intermediation in life and aging perception in retired teachers (Persian)]. Aging Psychology. 2016; 2(3):195-204. [Link]

- Crumbaugh JC, Maholick LT. An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl's concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1964; 20:200-7. [DOI:10.1002/1097-4679(196404)20:2<200::aid-jclp2270200203>3.0.co;2-u] [PMID]

- Mesrabadi J, Jafariyan S, Ostovar N. [Discriminative and construct validity of meaning in life questionnaire for Iranian students (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 7(1):83-90. [Link]

- Minarti M, Kastubi K, Fadilah N, Shifaza F. The effect of the combination of counseling and Dhikr interventions: Self-acceptance of the elderly in nursing home. International Journal of Advanced Health Science and Technology. 2022; 2(2):80-5. [DOI:10.35882/ijahst.v2i2.5]

- Bożek A, Nowak PF, Blukacz M. The relationship between spirituality, health-related behavior, and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:1997. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01997] [PMID]

- Harris S, Tao H. The impact of US nurses' personal religious and spiritual beliefs on their mental well-being and burnout: A path analysis. Journal of Religion and Health. 2022; 61(3):1772-91. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-021-01203-y] [PMID]

- Karimi A, Karsazi H, Fazeli Mehrabadi A. [Role of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in adolescent psychological well-being: Moderating effect of religious orientation (Persian)]. Pajouhan Scientific Journal. 2021; 19(2):58-65. [DOI:10.52547/psj.19.2.58]

- Safara M, Khanbabaee M, Khanbabaee M. The effectiveness of spirituality-based group counseling on purpose in life and personal growth in girls of divorced families. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2020; 22(4):203. [Link]

- Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Aschwanden D, Lee JH, Sesker AA, Stephan Y, et al. Sense of purpose in life and concurrent loneliness and risk of incident loneliness: An individual-participant meta-analysis of 135,227 individuals from 36 cohorts. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022; 309:211-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.084] [PMID]

- Yager J, Kay J. Purpose in life: Addressing transdiagnostic psychopathologies concerning patients' sense of purpose. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2023; 211(6):411-8. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001657] [PMID]

- Kim ES, Chen Y, Nakamura JS, Ryff CD, VanderWeele TJ. Sense of purpose in life and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health: An outcome-wide approach. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2022; 36(1):137-47. [DOI:10.1177/08901171211038545] [PMID]

- Gray JS, Ozer DJ, Rosenthal R. Goal conflict and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality. 2017; 66:27-37. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2016.12.003]

- Chen Y, Kim ES, Shields AE, VanderWeele TJ. Antecedents of purpose in life: Evidence from A lagged exposure-wide analysis. Cogent Psychology. 2020; 7(1):1825043. [DOI:10.1080/23311908.2020.1825043] [PMID]

- Kinoshita S, Hirooka N, Kusano T, Saito K, Nakamoto H. Does improvement in health-related lifestyle habits increase purpose in life among a health literate cohort? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8878. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17238878] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2024/01/31 | Accepted: 2024/05/13 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2024/01/31 | Accepted: 2024/05/13 | Published: 2025/03/2

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |