Volume 15, Issue 3 (May & June 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(3): 217-226 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abbasishavaz M, Morowati Sharifabad M A, Rahimian M, Jam-barsang S. Application of Health Education Theories and Models in Intimate Partner Violence Interventions Against Women in Iran: A Review Study. J Research Health 2025; 15 (3) :217-226

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2522-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2522-en.html

1- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,rahimianm7@gmail.com

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 660 kb]

(923 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3752 Views)

Full-Text: (1392 Views)

Introduction

Family is often thought of as a haven of safety and happiness; however, domestic violence is part of the experience of many family members, including women [1]. The most common form of violence experienced by women globally is intimate partner violence (IPV) [2]. IPV refers to violence or behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm [3].

The recognition of IPV as a social problem gained widespread attention in the 1970s, following a history of being regarded as a private issue that did not merit investigation or concern beyond the confines of the family. From a feminist perspective, wife abuse is more similar to rape and sexual harassment than to other forms of family violence [4]. IPV encompasses physical violence, emotional abuse, forced sexual activity, or other forms of controlling behavior that can result in physical, emotional, or sexual harm to the victim [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates indicate that globally, approximately one in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual IPV or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime [6]. The percentage of violence against women in all countries—even in developed countries that have established strong laws to prevent violence—is concerning [7] However, many women prefer to remain silent in the face of violence and even attempt to hide it [8].

Various studies have estimated the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran to range from 27% to 83% [9, 10, 11]. In a study in 2019, almost all (98.8%) participants stated that they had been exposed to a type of violence at least once. The prevalence of psychological violence was 80.8%, while verbal violence was reported at 95.4%. Physical violence occurred in 28.8% of the participants. Additionally, economic violence was reported by 45%, sexual violence by 28.3%, and all types of violence leading to injury occurred in 14.6% of the participants [12].

Today, IPV is a major obstacle to attaining social development purposes in society due to gender inequality. As a risk factor, IPV has adverse effects on women’s health both directly and indirectly [12]. All forms of domestic abuse have one goal: To control the victim and to maintain and continue this control [13]. In addition, violence against women poses a barrier to achieving development goals, and the associated economic implications further emphasize the significance of addressing issues related to violence against women [14].

Failure to resolve marital disputes and conflicts leads to the intensification of these unresolved problems during subsequent periods, and many couples do not even realize that most of the strategies they employ to deal with marital conflicts are somehow associated with physical violence, particularly emotional violence [15]. The reality is that, in many cases, violence is situational and bilateral; when a couple finds themselves in a conflict situation, they perceive violence as the only solution [16].

Numerous physical, psychological, and social injuries and even suicide have been reported as adverse effects of IPV [17]. Unfavorable health conditions, low quality of life, and increased use of health and medical services are also among the effects of violence. However, the impact of this destructive violence on the future generation is more destructive than it seems [18].

Studies targeting women indicate that interventions, such as education, support, counseling, and psychology have effectively reduced domestic violence cases against women [2, 19]. Teaching methods for dealing with men can assist abused women in managing their partners’ anger and in preventing or reducing violent behavior. Strategies such as avoiding confrontation, engaging in discussions after calming down, using positive language, seeking help and guidance from family elders, and visiting counseling centers are effective and efficient coping methods [20]. Studies in the field of couple therapy show that education and therapeutic interventions among couples have led to an increase in the quality of relationships, emotion regulation, improvement of attachment, receiving support and compassion, satisfaction with life, greater tolerance of turmoil, and an increase in the quality of married life [21]. However, a study conducted in Iran reported no change in the frequency of violence following educational intervention [22].

There is nothing more practical than a good theory [23]. Research has shown that effective educational programs are based on theory-based approaches. The use of behavior change models and theories increases the possibility of increasing the effectiveness of health education programs and helps to identify individual characteristics and the surrounding environment that affect behaviors [24]. The effectiveness of health education programs is increased by using behavior change theories and models [25]. In recent decades, health education models have been used to achieve large-scale behavioral change [26]. Several theories and models have been used in the world to control and reduce domestic violence against women [27, 28]. One of the key strategies in promoting health is to empower individuals within the community, which involves enhancing community ownership and control over their own destiny.

Empowering communities and strengthening individuals is one of the key strategies in promoting health, as it increases their ownership and control over their destiny [29]. Since domestic violence is known as one of the priorities and determinants of health in Iran [30], and given numerous studies and actions carried out in Iran have not positively impacted the reduction of IPV [31], the effectiveness of health education programs largely depends on the proper application of health education theories and models. Therefore, health education and health promotion specialists need to utilize behavior change theories and models. In this study, an attempt was made to identify studies in Iran that have used health education models and theories in their interventions to reduce or prevent IPV.

Methods

This is a narrative review of published articles on the application of health education models and theories in interventions against IPV targeting women in Iran. In this study, English keywords related to the subject, including domestic violence, IPV, spouse abuse, partner abuse, battered abuse sexual, intervention, theory/model, and Iran were used. These keywords were combined with Boolean operators such as “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT” to identify all relevant articles or exclude those with identified keywords. The search was conducted in reliable information databases, including Google Scholar, Scopus, and PubMed. Additionally, Persian keywords, such as domestic violence, wife abuse, intervention, and Theory/Model were searched in national databases, including the ElmNet, Magiran, Noormags, Scientific Information Database (SID), and CIVILICA.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Intervention studies where education using a model or theory aimed at preventing or reducing IPV is the primary focus; 2)Studies conducted in Iran; 3) Studies published between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2023; 4) Availability of the full text. The exclusion criteria were: Descriptive, qualitative, and review studies, as well as theses and unpublished studies.

Results

The process of selecting studies was as follows: First, 289 articles were extracted and entered into EndNote software, version 20 through database searches. Then, 249 articles were removed due to being repetitive or unrelated to the purpose of the study, and the titles and abstracts of 39 articles were reviewed. Thirty-one articles were excluded for not using a model or theory, and three articles were excluded due to the lack of an intervention using a model or theory. Finally, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, five articles were included in the study (Figure 1). One article was dedicated to predicting partner violence against spouses using the BASNEF model [32]. Two articles were excluded from the study due to using the PRECEDE- PROCEED and PEN3 models only to identify factors affecting domestic violence [33, 34]. Most of the studies and published interventions were based on training and skill development for women, utilizing methods to increase women’s self-efficacy, change women’s perceptions and motivations, cognitive behavioral therapy, coping therapy, Gestalt therapy, monotheistic integrated psychological intervention, spiritual counseling, resilience building, teaching life and communication skills, anger control, group therapy, couples therapy, social inoculation, family empowerment, adaptation, emotion regulation, patronage, and assistance.

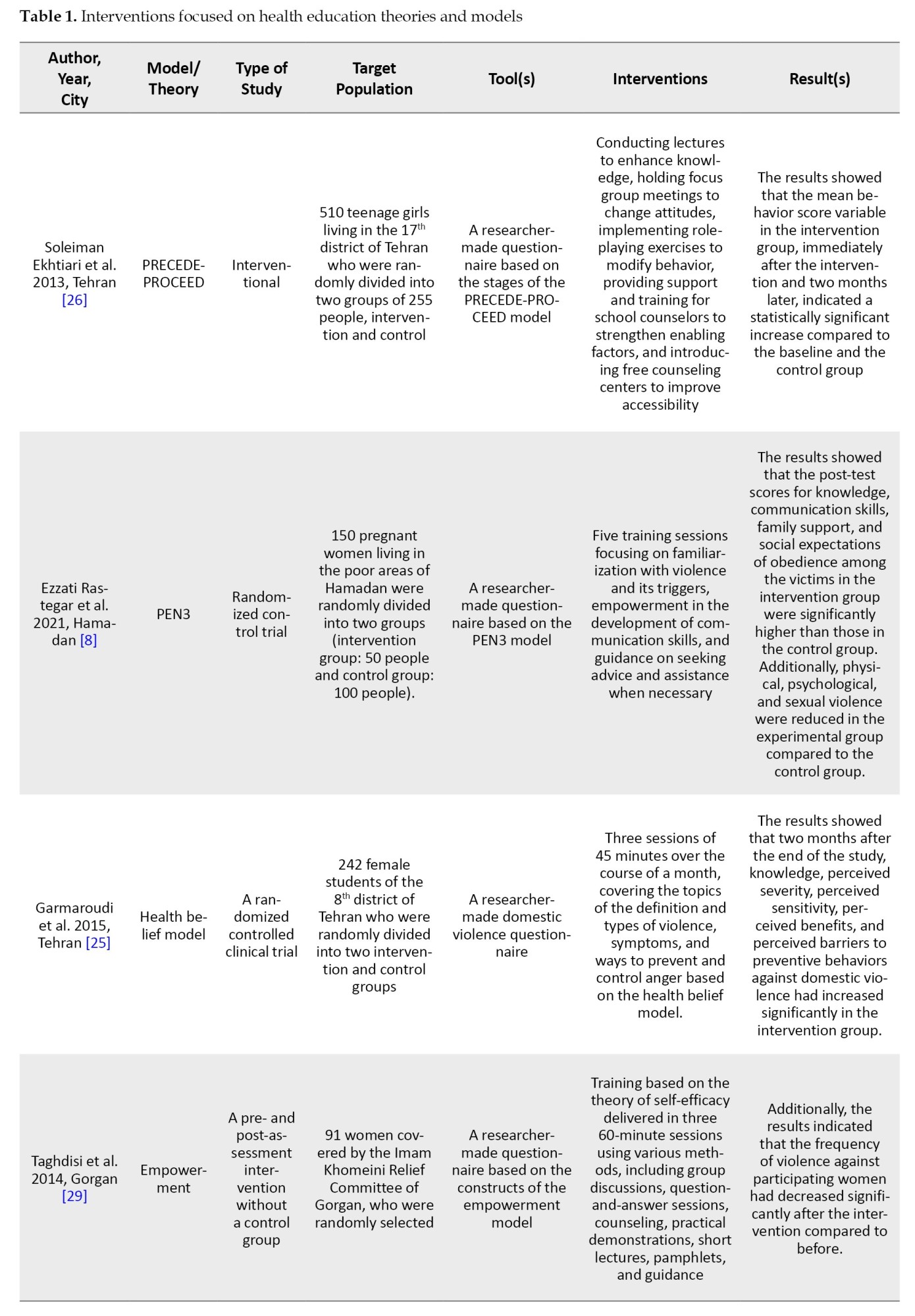

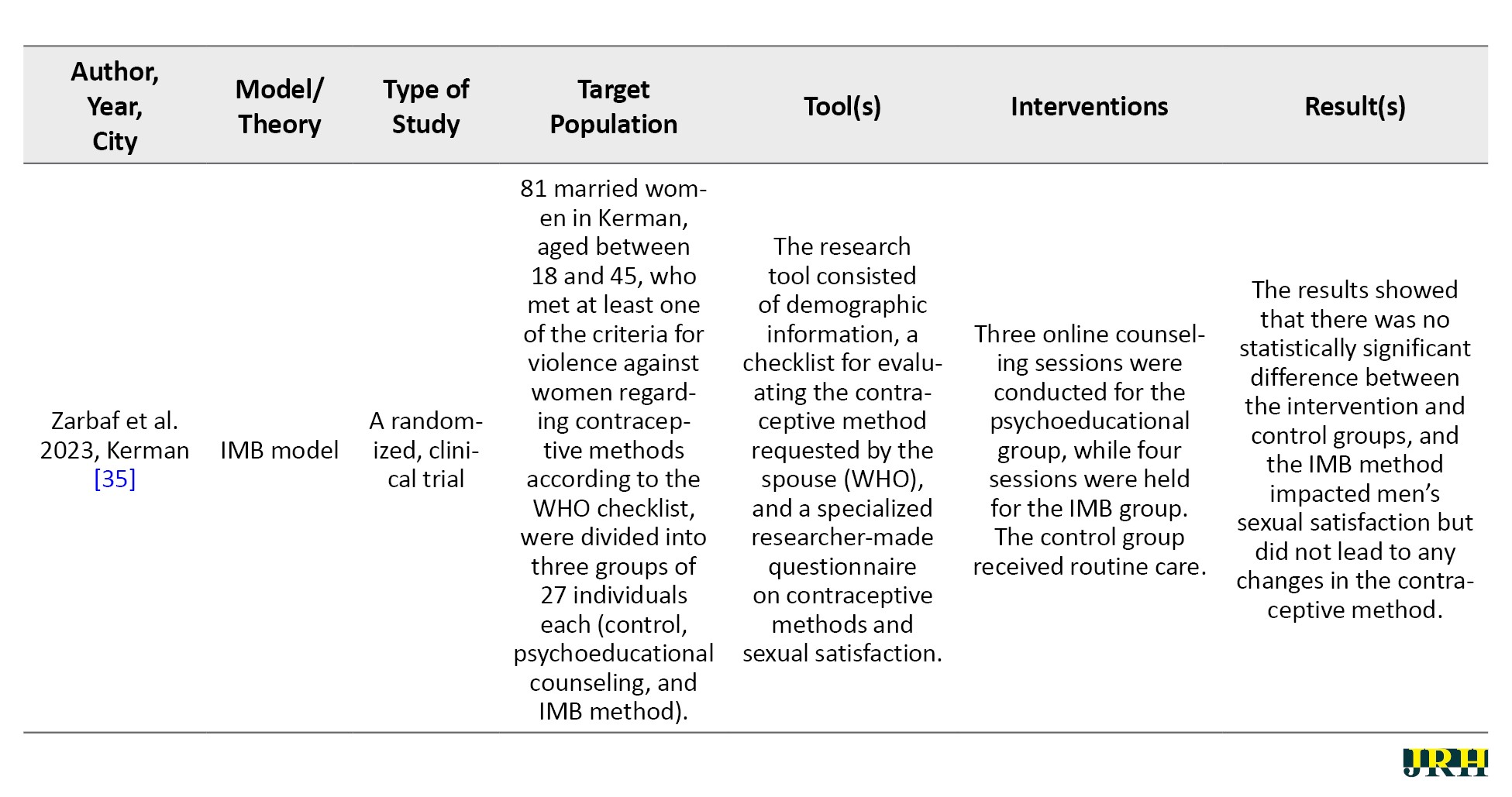

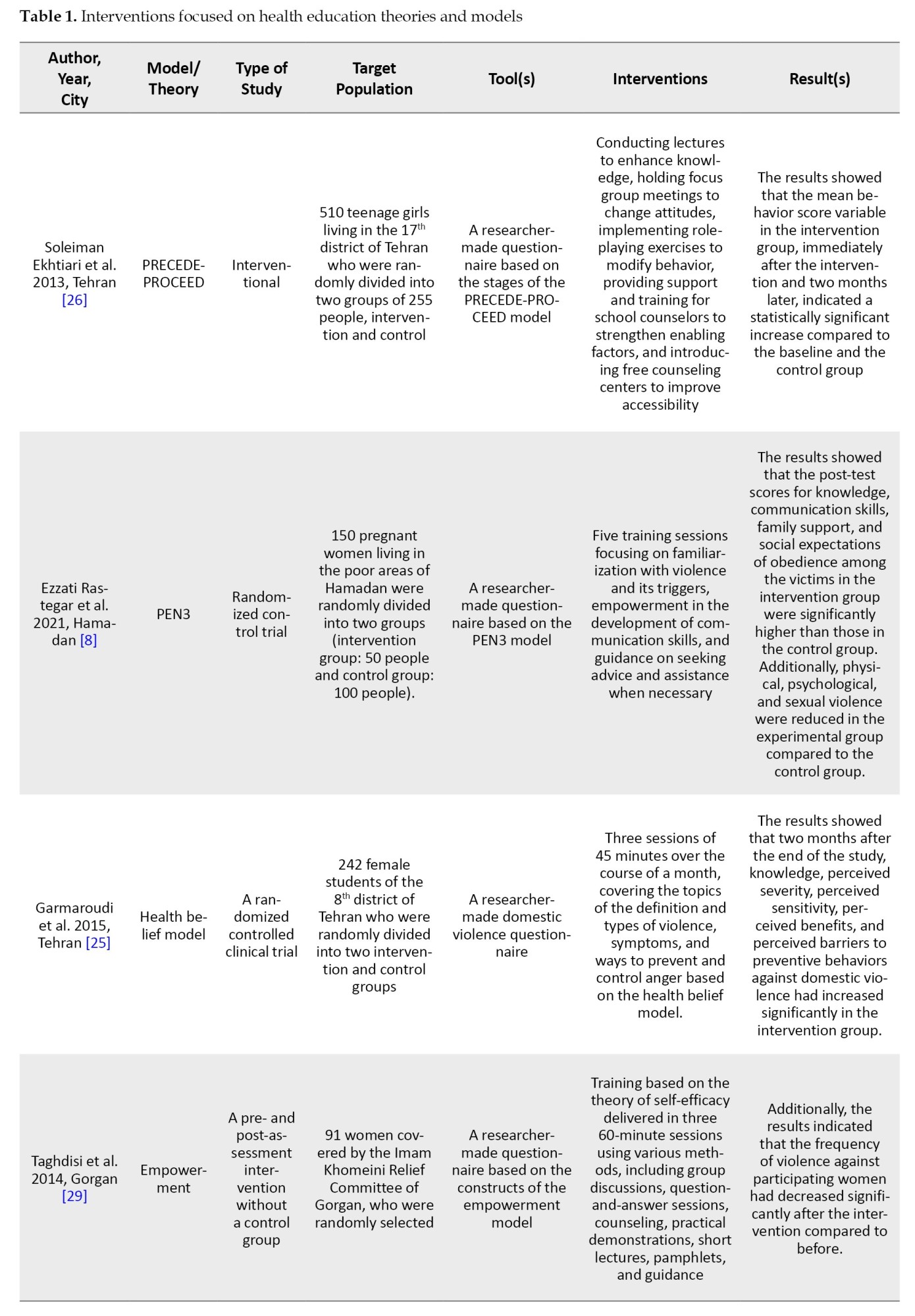

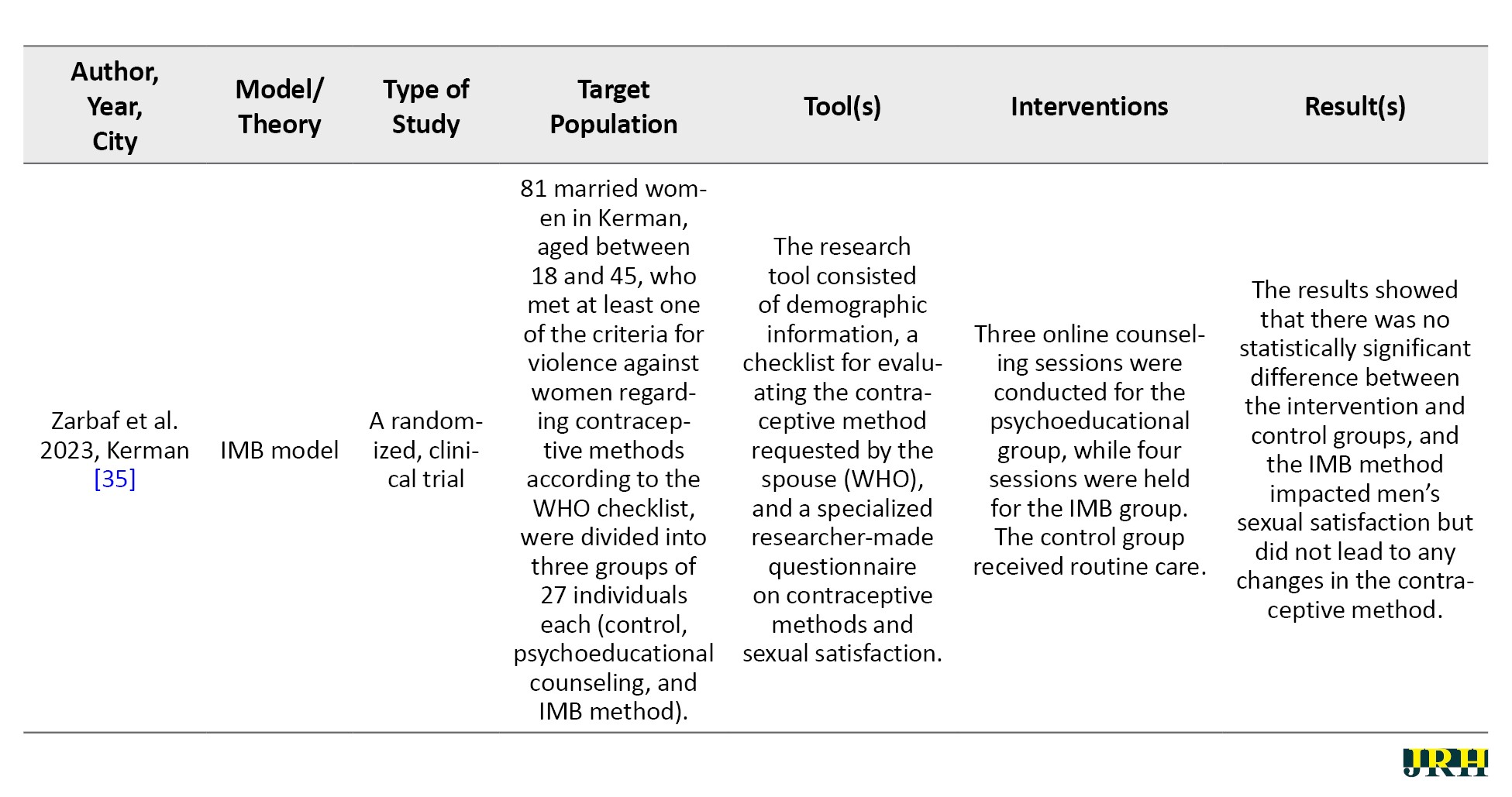

All the final articles included in the study process were prepared for extraction using a pre-prepared checklist. The checklist included the name of the first author, the model or theory used, the type of study, the target group of the intervention, the tools used, and the results (Table 1).

The intervention target group in model-based studies: The intervention target group in the studies by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. [26] and Garmaroudi et al. [25] included high school students covered by the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee. The study focused on the dignity of pregnant women and the sanctification of women.

Type of intervention: The sanctification study was a before-and-after intervention without a control group, while the other three studies were clinical trials with a control group.

Content of training and intervention: The training programs consisted of 3-5 face-to-face sessions, each lasting 45-60 minutes. The content included familiarization with types of violence, triggers of violence, prevention, and coping strategies, how to ask for help when necessary, and the empowerment of participants’ communication skills. These were the most important subjects covered in the training sessions.

Effectiveness of interventions: The study by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. [26], which was conducted using an intervention based on the PERECEDE-PROCEED model, showed that the average score of preventive behavior against domestic violence, as well as awareness and motivation to change behavior, and enabling and strengthening factors in the intervention group, significantly increased two months after the interventions compared to the beginning of the program and the control group. In Garmaroudi et al.’s study, which was conducted using an intervention based on the health belief model, the average scores for awareness, perceived sensitivity, perceived severity, perceived benefits and barriers, and behavior in the intervention group significantly increased three months after the training. However, the mean scores for the guide for action and self-efficacy did not show significant differences compared to before the training and the control group. The study by Ezzati Rastegar et al., which was planned and implemented based on the PEN3 model, introduced the intervention group to violence and its driving factors, as well as the development of communication skills, counselors, and supportive environments over five training sessions. After three months of educational intervention, the levels of physical, psychological, sexual, and economic violence in the intervention group decreased compared to before the training and the control group, although this difference was statistically significant only for sexual violence [8]. In the study by Taghdisi et al., which was conducted based on the empowerment model, participants showed significant increases in knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, and self-esteem, along with a significant decrease in the incidence of violence [29]. However, in the study by Zarbaf et al., the use of the model did not show a significant change in the reduction of contraception violence [35].

Discussion

The summary and analysis of the results of the studies showed the importance and effectiveness of interventions based on primary prevention or the reduction of domestic violence against women.

Domestic violence is a hidden threat and a complex, difficult, and widespread issue that we face in our lives. It affects people, especially women and girls, physically, psychologically, or socially, and is often perceived as uncontrollable. Actions and recommendations for addressing violence against women have been provided by world assemblies and international conventions, which primarily emphasize protective measures (such as the establishment of special centers, shelters, financial support, and social emergency services), legal frameworks, and educational and advisory initiatives. It is worth noting that, firstly, the solutions to deal with violence are in accordance with the specific culture of the West, and secondly, despite the efforts and measures taken, the incidence of violence against women has not decreased in these countries [36]. Given that multiple factors contribute to violence against spouses, preventive interventions should be as comprehensive and thorough as possible [37].

Rasulian et al. have proposed a model in Iran to prevent and reduce spousal abuse in the primary healthcare system [38]. Despite the emphasis in various studies on interventions targeting men [39-41], the studies conducted in Iran have primarily focused on interventions involving women, or in some cases, in the form of two-person counseling (woman and man). No interventions have been found that were implemented solely for men. Although couple-based interventions for other problematic antisocial behaviors, such as substance abuse, are quite effective as a treatment component, they are widely frowned upon in the context of IPV and often viewed as victim-blaming [42]. However, the results of previous studies showed that in cases where couples are committed to staying together, couple-based therapy can be effective in reducing IPV [43]. The results of couple therapy interventions in Iran have also been reported as favorable. Considering the role of religion and spirituality in addressing issues related to domestic violence [44], there have not been many studies conducted in our country that incorporate spiritual and religious interventions. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of health education models and theories in addressing health problems and the use of various models [45], such as the theory of reasoned action [27], the theory of planned behavior [46, 47], the stages of change model [48], and the theory of diffusion of innovation, the use of these frameworks remains limited in the context of IPV.

Few studies have been conducted in Iran to reduce or control violence against women using theoretical frameworks. The purpose of these models is to help identify and understand the effective factors influencing behavior and to determine how these factors operate [49]. The effectiveness of health education programs depends on the appropriate application of theories and models in health education [50]. Among the five studies found that were conducted based on intervention theories and models, two studies by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. and Garmaroudi et al. were implemented with student populations. Given the age range and the importance of schools and universities in shaping culture, these studies could also be conducted at the university level. In addition to lectures, the studies by McFarlane et al. used other methods in their interventions, which seem appropriate considering the greater effectiveness of combined methods in interventions, especially education that includes role-playing and the distribution of pamphlets [51, 52]. The improvement in the performance of participants in the intervention group in Soleiman Ekhtiari et al.’s study [26], compared to the baseline and control groups, is consistent with El-Kest et al.’s study [53]. Furthermore, the significant increase in knowledge, perceived severity, perceived sensitivity, perceived benefits and barriers, and preventive behaviors against domestic violence in the intervention group compared to the control group in Garmaroudi et al.’s study aligns with the findings of Burke [54].

Despite the fact that the information-motivation-behavioral (IMB) model was introduced as an effective intervention factor and predictor of behavior in the studies by Fisher et al. [55] and Mittal et al. [56], the study by Zarbaf et al. found no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups after the intervention [35]. This lack of difference may be attributed to the cultural differences between societies. The ultimate goal of interventions is to reduce violence against women by an intimate partner; however, in the studies by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. and Garmaroudi et al., almost all participants were single, making it practically impossible to measure this goal [25, 26]. Also, this review did not include any studies that demonstrated the participation of trustee organizations, such as those related to sports and youth, welfare, etc. In general, the results of the present study also showed that the use of health education models and theories to reduce and prevent IPV against women in Iran has been effective, which is consistent with findings from studies conducted abroad.

Conclusion

The use of interventions based on models and theories of health education and health promotion is effective in preventing and reducing IPV. The theory of planned behavior, the theory of reason action, the PERECEDE-PROCEED model, the health belief model, the BASNEF model, the PEN3 model, and other planning and behavior change models can be used to address IPV in Iran. However, due to the ineffectiveness and lack of positive impact of some interventions in Iran, IPV has not been significantly reduced. It is suggested that future studies be conducted based on various theories and models of health education, involving both sexes and different age groups, with the participation of relevant organizations and custodial offices. Furthermore, the failure to investigate IPV in Iran as a public health issue, along with its study by psychologists and sociologists, has led to the limited use of models and theories of health education and health promotion.

Study limitations

Based on the search strategy employed in the study, we included all studies with available full texts in English and Persian that investigated the interventions in both control and intervention groups. Additionally, we excluded articles published in preprint databases due to a lack of peer review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

No ethical considerations were considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Family is often thought of as a haven of safety and happiness; however, domestic violence is part of the experience of many family members, including women [1]. The most common form of violence experienced by women globally is intimate partner violence (IPV) [2]. IPV refers to violence or behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm [3].

The recognition of IPV as a social problem gained widespread attention in the 1970s, following a history of being regarded as a private issue that did not merit investigation or concern beyond the confines of the family. From a feminist perspective, wife abuse is more similar to rape and sexual harassment than to other forms of family violence [4]. IPV encompasses physical violence, emotional abuse, forced sexual activity, or other forms of controlling behavior that can result in physical, emotional, or sexual harm to the victim [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates indicate that globally, approximately one in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual IPV or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime [6]. The percentage of violence against women in all countries—even in developed countries that have established strong laws to prevent violence—is concerning [7] However, many women prefer to remain silent in the face of violence and even attempt to hide it [8].

Various studies have estimated the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran to range from 27% to 83% [9, 10, 11]. In a study in 2019, almost all (98.8%) participants stated that they had been exposed to a type of violence at least once. The prevalence of psychological violence was 80.8%, while verbal violence was reported at 95.4%. Physical violence occurred in 28.8% of the participants. Additionally, economic violence was reported by 45%, sexual violence by 28.3%, and all types of violence leading to injury occurred in 14.6% of the participants [12].

Today, IPV is a major obstacle to attaining social development purposes in society due to gender inequality. As a risk factor, IPV has adverse effects on women’s health both directly and indirectly [12]. All forms of domestic abuse have one goal: To control the victim and to maintain and continue this control [13]. In addition, violence against women poses a barrier to achieving development goals, and the associated economic implications further emphasize the significance of addressing issues related to violence against women [14].

Failure to resolve marital disputes and conflicts leads to the intensification of these unresolved problems during subsequent periods, and many couples do not even realize that most of the strategies they employ to deal with marital conflicts are somehow associated with physical violence, particularly emotional violence [15]. The reality is that, in many cases, violence is situational and bilateral; when a couple finds themselves in a conflict situation, they perceive violence as the only solution [16].

Numerous physical, psychological, and social injuries and even suicide have been reported as adverse effects of IPV [17]. Unfavorable health conditions, low quality of life, and increased use of health and medical services are also among the effects of violence. However, the impact of this destructive violence on the future generation is more destructive than it seems [18].

Studies targeting women indicate that interventions, such as education, support, counseling, and psychology have effectively reduced domestic violence cases against women [2, 19]. Teaching methods for dealing with men can assist abused women in managing their partners’ anger and in preventing or reducing violent behavior. Strategies such as avoiding confrontation, engaging in discussions after calming down, using positive language, seeking help and guidance from family elders, and visiting counseling centers are effective and efficient coping methods [20]. Studies in the field of couple therapy show that education and therapeutic interventions among couples have led to an increase in the quality of relationships, emotion regulation, improvement of attachment, receiving support and compassion, satisfaction with life, greater tolerance of turmoil, and an increase in the quality of married life [21]. However, a study conducted in Iran reported no change in the frequency of violence following educational intervention [22].

There is nothing more practical than a good theory [23]. Research has shown that effective educational programs are based on theory-based approaches. The use of behavior change models and theories increases the possibility of increasing the effectiveness of health education programs and helps to identify individual characteristics and the surrounding environment that affect behaviors [24]. The effectiveness of health education programs is increased by using behavior change theories and models [25]. In recent decades, health education models have been used to achieve large-scale behavioral change [26]. Several theories and models have been used in the world to control and reduce domestic violence against women [27, 28]. One of the key strategies in promoting health is to empower individuals within the community, which involves enhancing community ownership and control over their own destiny.

Empowering communities and strengthening individuals is one of the key strategies in promoting health, as it increases their ownership and control over their destiny [29]. Since domestic violence is known as one of the priorities and determinants of health in Iran [30], and given numerous studies and actions carried out in Iran have not positively impacted the reduction of IPV [31], the effectiveness of health education programs largely depends on the proper application of health education theories and models. Therefore, health education and health promotion specialists need to utilize behavior change theories and models. In this study, an attempt was made to identify studies in Iran that have used health education models and theories in their interventions to reduce or prevent IPV.

Methods

This is a narrative review of published articles on the application of health education models and theories in interventions against IPV targeting women in Iran. In this study, English keywords related to the subject, including domestic violence, IPV, spouse abuse, partner abuse, battered abuse sexual, intervention, theory/model, and Iran were used. These keywords were combined with Boolean operators such as “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT” to identify all relevant articles or exclude those with identified keywords. The search was conducted in reliable information databases, including Google Scholar, Scopus, and PubMed. Additionally, Persian keywords, such as domestic violence, wife abuse, intervention, and Theory/Model were searched in national databases, including the ElmNet, Magiran, Noormags, Scientific Information Database (SID), and CIVILICA.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Intervention studies where education using a model or theory aimed at preventing or reducing IPV is the primary focus; 2)Studies conducted in Iran; 3) Studies published between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2023; 4) Availability of the full text. The exclusion criteria were: Descriptive, qualitative, and review studies, as well as theses and unpublished studies.

Results

The process of selecting studies was as follows: First, 289 articles were extracted and entered into EndNote software, version 20 through database searches. Then, 249 articles were removed due to being repetitive or unrelated to the purpose of the study, and the titles and abstracts of 39 articles were reviewed. Thirty-one articles were excluded for not using a model or theory, and three articles were excluded due to the lack of an intervention using a model or theory. Finally, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, five articles were included in the study (Figure 1). One article was dedicated to predicting partner violence against spouses using the BASNEF model [32]. Two articles were excluded from the study due to using the PRECEDE- PROCEED and PEN3 models only to identify factors affecting domestic violence [33, 34]. Most of the studies and published interventions were based on training and skill development for women, utilizing methods to increase women’s self-efficacy, change women’s perceptions and motivations, cognitive behavioral therapy, coping therapy, Gestalt therapy, monotheistic integrated psychological intervention, spiritual counseling, resilience building, teaching life and communication skills, anger control, group therapy, couples therapy, social inoculation, family empowerment, adaptation, emotion regulation, patronage, and assistance.

All the final articles included in the study process were prepared for extraction using a pre-prepared checklist. The checklist included the name of the first author, the model or theory used, the type of study, the target group of the intervention, the tools used, and the results (Table 1).

The intervention target group in model-based studies: The intervention target group in the studies by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. [26] and Garmaroudi et al. [25] included high school students covered by the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee. The study focused on the dignity of pregnant women and the sanctification of women.

Type of intervention: The sanctification study was a before-and-after intervention without a control group, while the other three studies were clinical trials with a control group.

Content of training and intervention: The training programs consisted of 3-5 face-to-face sessions, each lasting 45-60 minutes. The content included familiarization with types of violence, triggers of violence, prevention, and coping strategies, how to ask for help when necessary, and the empowerment of participants’ communication skills. These were the most important subjects covered in the training sessions.

Effectiveness of interventions: The study by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. [26], which was conducted using an intervention based on the PERECEDE-PROCEED model, showed that the average score of preventive behavior against domestic violence, as well as awareness and motivation to change behavior, and enabling and strengthening factors in the intervention group, significantly increased two months after the interventions compared to the beginning of the program and the control group. In Garmaroudi et al.’s study, which was conducted using an intervention based on the health belief model, the average scores for awareness, perceived sensitivity, perceived severity, perceived benefits and barriers, and behavior in the intervention group significantly increased three months after the training. However, the mean scores for the guide for action and self-efficacy did not show significant differences compared to before the training and the control group. The study by Ezzati Rastegar et al., which was planned and implemented based on the PEN3 model, introduced the intervention group to violence and its driving factors, as well as the development of communication skills, counselors, and supportive environments over five training sessions. After three months of educational intervention, the levels of physical, psychological, sexual, and economic violence in the intervention group decreased compared to before the training and the control group, although this difference was statistically significant only for sexual violence [8]. In the study by Taghdisi et al., which was conducted based on the empowerment model, participants showed significant increases in knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, and self-esteem, along with a significant decrease in the incidence of violence [29]. However, in the study by Zarbaf et al., the use of the model did not show a significant change in the reduction of contraception violence [35].

Discussion

The summary and analysis of the results of the studies showed the importance and effectiveness of interventions based on primary prevention or the reduction of domestic violence against women.

Domestic violence is a hidden threat and a complex, difficult, and widespread issue that we face in our lives. It affects people, especially women and girls, physically, psychologically, or socially, and is often perceived as uncontrollable. Actions and recommendations for addressing violence against women have been provided by world assemblies and international conventions, which primarily emphasize protective measures (such as the establishment of special centers, shelters, financial support, and social emergency services), legal frameworks, and educational and advisory initiatives. It is worth noting that, firstly, the solutions to deal with violence are in accordance with the specific culture of the West, and secondly, despite the efforts and measures taken, the incidence of violence against women has not decreased in these countries [36]. Given that multiple factors contribute to violence against spouses, preventive interventions should be as comprehensive and thorough as possible [37].

Rasulian et al. have proposed a model in Iran to prevent and reduce spousal abuse in the primary healthcare system [38]. Despite the emphasis in various studies on interventions targeting men [39-41], the studies conducted in Iran have primarily focused on interventions involving women, or in some cases, in the form of two-person counseling (woman and man). No interventions have been found that were implemented solely for men. Although couple-based interventions for other problematic antisocial behaviors, such as substance abuse, are quite effective as a treatment component, they are widely frowned upon in the context of IPV and often viewed as victim-blaming [42]. However, the results of previous studies showed that in cases where couples are committed to staying together, couple-based therapy can be effective in reducing IPV [43]. The results of couple therapy interventions in Iran have also been reported as favorable. Considering the role of religion and spirituality in addressing issues related to domestic violence [44], there have not been many studies conducted in our country that incorporate spiritual and religious interventions. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of health education models and theories in addressing health problems and the use of various models [45], such as the theory of reasoned action [27], the theory of planned behavior [46, 47], the stages of change model [48], and the theory of diffusion of innovation, the use of these frameworks remains limited in the context of IPV.

Few studies have been conducted in Iran to reduce or control violence against women using theoretical frameworks. The purpose of these models is to help identify and understand the effective factors influencing behavior and to determine how these factors operate [49]. The effectiveness of health education programs depends on the appropriate application of theories and models in health education [50]. Among the five studies found that were conducted based on intervention theories and models, two studies by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. and Garmaroudi et al. were implemented with student populations. Given the age range and the importance of schools and universities in shaping culture, these studies could also be conducted at the university level. In addition to lectures, the studies by McFarlane et al. used other methods in their interventions, which seem appropriate considering the greater effectiveness of combined methods in interventions, especially education that includes role-playing and the distribution of pamphlets [51, 52]. The improvement in the performance of participants in the intervention group in Soleiman Ekhtiari et al.’s study [26], compared to the baseline and control groups, is consistent with El-Kest et al.’s study [53]. Furthermore, the significant increase in knowledge, perceived severity, perceived sensitivity, perceived benefits and barriers, and preventive behaviors against domestic violence in the intervention group compared to the control group in Garmaroudi et al.’s study aligns with the findings of Burke [54].

Despite the fact that the information-motivation-behavioral (IMB) model was introduced as an effective intervention factor and predictor of behavior in the studies by Fisher et al. [55] and Mittal et al. [56], the study by Zarbaf et al. found no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups after the intervention [35]. This lack of difference may be attributed to the cultural differences between societies. The ultimate goal of interventions is to reduce violence against women by an intimate partner; however, in the studies by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al. and Garmaroudi et al., almost all participants were single, making it practically impossible to measure this goal [25, 26]. Also, this review did not include any studies that demonstrated the participation of trustee organizations, such as those related to sports and youth, welfare, etc. In general, the results of the present study also showed that the use of health education models and theories to reduce and prevent IPV against women in Iran has been effective, which is consistent with findings from studies conducted abroad.

Conclusion

The use of interventions based on models and theories of health education and health promotion is effective in preventing and reducing IPV. The theory of planned behavior, the theory of reason action, the PERECEDE-PROCEED model, the health belief model, the BASNEF model, the PEN3 model, and other planning and behavior change models can be used to address IPV in Iran. However, due to the ineffectiveness and lack of positive impact of some interventions in Iran, IPV has not been significantly reduced. It is suggested that future studies be conducted based on various theories and models of health education, involving both sexes and different age groups, with the participation of relevant organizations and custodial offices. Furthermore, the failure to investigate IPV in Iran as a public health issue, along with its study by psychologists and sociologists, has led to the limited use of models and theories of health education and health promotion.

Study limitations

Based on the search strategy employed in the study, we included all studies with available full texts in English and Persian that investigated the interventions in both control and intervention groups. Additionally, we excluded articles published in preprint databases due to a lack of peer review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

No ethical considerations were considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Darvishnia Fandari A, Aghayousef A, sobhi-gharamaleki N. [The effectiveness of "coping therapy" on general self-efficacy, psychological well-being and resilience in women under domestic violence (Persian)]. Journal of Health Promotion Management. 2022; 11(1):140-54. [Link]

- Cowlishaw S, Sbisa A, Freijah I, Kartal D, Mulligan A, Notarianni M, et al. Health service interventions for intimate partner violence among military personnel and veterans: A framework and scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3551. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19063551] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fridman SE, Prakash N. Intimate partner violence (IPV) as a public health crisis: A discussion of intersectionality and its role in better health outcomes for immigrant women in the United States (US). Cureus. 2022; 14(5):e25257. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.25257]

- Lawson J. Sociological theories of intimate partner violence. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2012; 22(5):572-90. [DOI:10.1080/10911359.2011.598748]

- Wang T, Liu Y, Li Z, Liu K, Xu Y, Shi W, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2017; 12(10):e0175108. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0175108] [PMID] [PMCID]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Violence against women [Internet]. 2024 [2024 March 25]. Available from: [Link]

- Khaki D, Kafie SM, Moazami S, Tahmasebi J. Effectiveness of communication skills training on reducing psychological and verbal violence in women victims of domestic violence in Karaj. Journal of Policing and Social Studies of Women and Family. 2020; 8(2):315-3. [Link]

- Rastegar KE, Moeini B, Rezapur-Shahkolai F, Naghdi A, Karami M, Jahanfar S. The impact of preventive interventions on intimate partner violence among pregnant women resident in Hamadan city slum areas using the pen-3 model: Control randomized trial study. Korean Journal of Family Medicine. 2021; 42(6):438-44. [DOI:10.4082/kjfm.20.0118] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rahebi SM, Rahnavardi M, Rezaie-Chamani S, Nazari M, Sabetghadam S. Relationship between domestic violence and infertility. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2019; 25(8):537-42. [DOI:10.26719/emhj.19.001] [PMID]

- Ahmadi R, Soleimani R, Jalali MM, Yousefnezhad A, Roshandel Rad M, Eskandari A. Association of intimate partner violence with sociodemographic factors in married women: A population-based study in Iran. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2017; 22(7):834-44. [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2016.1238489] [PMID]

- Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Hossein Abbasi N, Mehrdad N. The prevalence of violence against Iranian women and its related factors. Global Journal of Health Science. 2014; 7(3):37-45. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n3p37] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mohammadbeigi A, Sajadi M, Ahmadli R, Asgarian A, Khazaei S, Afrashteh S, et al. Intimate partner violence against Iranian women. The National Medical Journal of India. 2019; 32(2):67-71. [DOI:10.4103/0970-258X.275343] [PMID]

- Ekta S, Rakesh Kumar B. Domestic violent. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2016; 4(1):2349-3429. [DOI:10.25215/0401.022]

- Asadi ZS, Hosseini VM, Hashemian M, Akaberi A. Application of BASNEF model in prediction of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women. Asian Women. 2013; 29(1):27-45. [Link]

- Smith SG, Basile KC, Gilbert LK, Merrick MT, Patel N, Walling M, et al. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010-2012 state report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Link]

- Aslani K, Khodadadi Andarie F, Amanelahi A, Rajabi G, Stith S. [The effectiveness of domestic violence-focused couple therapy on violence against women: Intervention in maladjusted couple relationships living in Ahvaz (Persian)]. Family Counseling and Psychotherapy. 2020; 9(2):213-32. [DOI:org/10.34785/J015.2019.009]

- Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C; WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008; 371(9619):1165-72. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X] [PMID]

- Boroumandfar K, Javaheri S, Ehsanpour S, Abedi A. Reviewing the effect of two methods of educational package and social inoculation on changing the attitudes towards domestic violence against women. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 2010; 15(Suppl 1):283-91. [PMID]

- Mittal M, Paden McCormick A, Palit M, Trabold N, Spencer C. A meta-analysis and systematic review of community-based intimate partner violence interventions in India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5277. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20075277] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Yazdanpanah Dolatabadi A, Towhidi A, Rahmati A. Designing an instructional package for coping with domestic violence and the effectiveness of the package instruction on spousal violence and children’s academic enthusiasm. Quarterly Social Psychology Research. 2021; 11(43):1-18. [DOI:10.22034/spr.2021.277874.1636]

- Mostajeran M, Jazayeri RS, Fatehizade M. [The effect of integrated emotion-focused therapy (grinbeerg’s) and compassion focused therapy on marital quality of life and married women (Persian)]. Research in Cognitive and Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(1):85-106. [DOI:10.22108/cbs.2022.130801.1576]

- Noughani F, Mohtashami J. Effect of education on prevention of domestic violence against women. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011; 6(2):80-3. [PMID]

- Lewis M. There is nothing as practical as a good theory. Hove: Language Teaching Publications; 2000. [Link]

- Farjam E, Charoghchian KE, Ebrahimi S, Sadeghi S, Afzalaghaee M, Peyman N. [Application of models and theories of health education and health promotion in the prevention of substance abuse in adolescents: A systematic review (Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. 2023; 15(2):71-9. [Link]

- Garmaroudi G, Sarlak B, Sadeghi R, Rahimi Foroushani A. [The effect of an intervention based on the health belief model on preventive behaviors of domestic violence in female high school students (Persian)]. Journal of Knowledge & Health Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 11(1):74-69. [DOI:10.22100/jkh.v11i1.1302]

- Soleiman Ekhtiari Y, Shojaeizadeh D, Rahimi Foroushani A, Ghofranipour F, Ahmadi B. The effect of an intervention based on the precede-proceed model on preventive behaviors of domestic violence among Iranian high school girls. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2013; 15(1):21-8. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.3517] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Nabi RL, Southwell B, Hornik R. Predicting intentions versus predicting behaviors: Domestic violence prevention from a theory of reasoned action perspective. Health Communication. 2002; 14(4):429-49. [DOI:10.1207/S15327027HC1404_2] [PMID]

- Brown T. Cultural heterogeneity and intimate partner violence in 17 developing countries: A test of competing theories [Masters Thesis]. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina; 2015. [Link]

- Taghdisi MH, Estebsari F, Dastoorpour M, Jamshidi E, Jamalzadeh F, Latifi M. The impact of educational intervention based on empowerment model in preventing violence against women. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2014; 16(7):e14432. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.14432] [PMID]

- Rahimi-Movaghar A, Amin-Esmaeili M, Hefazi M, Rafiey H, Shariat SV, Sharifi V, et al. [National priority setting for mental health in Iran (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2014; 20(3):189-200. [Link]

- Shekarbeygi A, Mostame R. [Meta-analysis of studies on violence against women (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Sociology. 2013; 15(2):153-77. [Link]

- Sadat-Asadi Z, Moghaddamhosseini V, Hashemian M, Akaberi A. Application of BASNEF model in prediction of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women. Asian Women. 2013; 29(1):27-45. [Link]

- Fouladi N, Feizi I, Pourfarzi F, Yousefi S, Alimohammadi S, Mehrara E, et al. Factors affecting behaviors of women with breast cancer facing intimate partner violence based on precede-proceed model. Journal of Caring Sciences. 2021; 10(2):89-95. [DOI:10.34172/jcs.2021.017] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Moeini B, Rezapur-Shahkolai F, Jahanfar S, Naghdi A, Karami M, Ezzati-Rastegar K. Utilizing the PEN-3 model to identify socio-cultural factors affecting intimate partner violence against pregnant women in Suburban Hamadan. Health Care for Women International. 2019; 40(11):1212-28. [DOI:10.1080/07399332.2019.1578777] [PMID]

- Zarbaf A, Ahmadi A, Rafati E, Ghorbani F, Pour MG, Alidousti K. Comparison between the effect of the information-motivation-behavioral (IMB) model and psychoeducational counseling on sexual satisfaction and contraception method used under the coercion of the spouse in Iranian women: A randomized, clinical trial. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2023; 45(8):e447-55. [DOI:10.1055/s-0043-1772487] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Aliverdinia A, Habibi M. [The study of university male students attitude toward violence against woman in family context: An empirical test of akers social learning theory (Persian)]. Strategic Research on Social Problems in Iran. 2016; 4(3):15-38. [Link]

- Little L, Kantor GK. Using ecological theory to understand intimate partner violence and child maltreatment. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2002; 19(3):133-45. [DOI:10.1207/S15327655JCHN1903_02] [PMID]

- Rasulian M, Bolhari J, Nojomi M, Habib S, Mirzaei.Khoshalani M. Theories and interventional models of intimate partner violence: Suggesting an interventional model based on primary health care system in Iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2015; 12(1):3-16. [Link]

- Berkowitz AD. Working with men to prevent violence against women: An overview (part one). National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. 2004; 9(2):1-7. [Link]

- Maman S, Mulawa MI, Balvanz P, McNaughton Reyes HL, Kilonzo MN, Yamanis TJ, et al. Results from a cluster-randomized trial to evaluate a microfinance and peer health leadership intervention to prevent HIV and intimate partner violence among social networks of Tanzanian men. Plos One. 2020; 15(3):e0230371. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0230371] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Stanley N, Fell B, Miller P, Thomson G, Watson J. Men's talk: Men's understandings of violence against women and motivations for change. Violence Against Women. 2012; 18(11):1300-18. [DOI:10.1177/1077801212470547] [PMID]

- Moin R. Growth building jobs and prosperity in developing countries. London: Department for International Development; 2008. [Link]

- Hartmann MA, Datta S, Banay RF, Caetano V, Floreak R, Appaiah P, et al. Designing a pilot study protocol to test a male alcohol use and intimate partner violence reduction intervention in India: Beautiful home. Frontiers in Public Health. 2018; 6:218. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00218] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Muralidharan S, La Ferle C, Pookulangara S. Studying the impact of religious symbols on domestic violence prevention in India: Applying the theory of reasoned action to bystanders’ reporting intentions. International Journal of Advertising. 2018; 37(4):609-32. [DOI:10.1080/02650487.2017.1339659]

- Hajari A, Shams M, Afrooghi S, Fadaei Nobari R, Abaspoor Najafabadi R. [Using the precede-proceed model in needs assessment for the prevention of brucellosis in rural areas of Isfahan, Iran (Persian)]. Armaghane Danesh. 2016; 21(4):396-409. [Link]

- Kernsmith P. Treating perpetrators of domestic violence: Gender differences in the applicability of the theory of planned behavior. Sex Roles. 2005; 52(11):757-70. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-005-4197-5]

- Hill J. Predictors and consequences of decision making in domestic violence [master thesis]. Preston: University of Central Lancashire; 2009. [Link]

- Walker K, Bowen E, Brown S, Sleath E. Desistance from intimate partner violence: A conceptual model and framework for practitioners for managing the process of change. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015; 30(15):2726-50. [DOI:10.1177/0886260514553634] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Karimy M, Gallali M, Niknami S, Aminshokravi F, Tavafian S. [The effect of health education program based on health belief model on the performance of pap smear test among women referring to health care centers in Zarandieh (Persian)]. Pars Journal of Medical Sciences. 2022; 10(1):53-9. [DOI:10.29252/jmj.10.1.53]

- Hasani M, Khoram R, Ghaffari M, Niknami S. [The effect of education, based on health belief model on breast self-examination in health liaisons of Zarandieh city (Persian)]. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2008; 10(4):283-91. [Link]

- McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Silva C, Reel S. Safety behaviors of abused women after an intervention during pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1998; 27(1):64-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02592.x] [PMID]

- McFarlane J, Soeken K, Wiist W. An evaluation of interventions to decrease intimate partner violence to pregnant women. Public Health Nursing. 2000; 17(6):443-51. [DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00443.x] [PMID]

- El-Kest HR, Fouda LM, Alhossiny EA, Khaton SE. The effect of an educational intervention program on prevention of domestic violence among adolescent girls. Journal of Nursing and Health Science. 2018; 7(3):73-88. [DOI:10.9790/1959-0703077382]

- Burke AJ. An investigation of intimate partner violence perceptions in nine Appalachian Ohio Counties: A health belief model approach [doctoral thesis]. Kent: Kent State University; 2015. [Link]

- Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Link]

- Mittal M, Senn TE, Carey MP. Intimate partner violence and condom use among women: does the information-motivation-behavioral skills model explain sexual risk behavior? AIDS and Behavior. 2012; 16(4):1011-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10461-011-9949-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

● Health Education

Received: 2024/03/19 | Accepted: 2024/09/17 | Published: 2025/05/30

Received: 2024/03/19 | Accepted: 2024/09/17 | Published: 2025/05/30

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |