Volume 15, Issue 1 (Jan & Feb 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(1): 15-26 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: KEC.2023.12C1.

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Karstensen V, Hooshmandi R, Bastholm M. Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Qualitative Study of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs. J Research Health 2025; 15 (1) :15-26

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2554-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2554-en.html

1- Department of Regional Health Research, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark. , valekarstensen@health.sdu.dk

2- Liva Healthcare, Research and Innovation, Copenhagen, Denmark.

3- Research Unit for General Practice, Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences,University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

2- Liva Healthcare, Research and Innovation, Copenhagen, Denmark.

3- Research Unit for General Practice, Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences,University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Full-Text [PDF 748 kb]

(903 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4039 Views)

Full-Text: (1517 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period characterized by significant physical, emotional, and social changes. It is during this time that mental health issues often first emerge, making it essential to understand and address the mental health literacy of this age group. Given the rising prevalence of mental health issues among adolescents, understanding their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs is crucial for improving mental health outcomes [1-3].

Adolescents face unique challenges in identifying and addressing mental health concerns due to various factors, including stigma, lack of information, and cultural influences [4]. The concept of mental health literacy, introduced by Burns and Rapee, refers to the knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders that aid their recognition, management, or prevention [5]. High levels of mental health literacy are associated with positive attitudes toward seeking help and better mental health outcomes [6]. However, adolescents often display significant gaps in mental health literacy, which can lead to delayed help-seeking and poorer mental health outcomes [6]. Conversely, dysfunctional family communication patterns can negatively impact adolescents’ mental health literacy and overall well-being [7]. Moreover, cultural narratives and traditions significantly influence family mental health, often dictating the stigmatization or acceptance of mental health issues [8]. Understanding these gaps and addressing them through targeted interventions is critical.

Globalization has further complicated the influence of family traditions and values on adolescents’ mental health literacy. As cultural norms evolve, the clash between traditional values and modern mental health perspectives can create confusion and hinder effective communication about mental health [9]. Understanding these cultural influences is crucial for developing culturally sensitive mental health interventions.

Educational settings also play a pivotal role in shaping mental health literacy. School-based mental health promotion programs have shown effectiveness in improving mental health knowledge and attitudes among adolescents [10]. However, the success of these programs often depends on the context and the extent to which they address the specific needs and concerns of adolescents. Peer-led interventions have also been highlighted as effective in low-resource settings, emphasizing the importance of peer influence in shaping mental health behaviors [11].

Adolescents’ experiences with mental health services reveal critical insights into their perceptions and barriers to accessing care. Studies have shown that adolescents often perceive mental health services as stigmatizing and taboo, which discourages them from seeking help [12]. Additionally, the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the perceived effectiveness of mental health interventions significantly influence adolescents’ willingness to engage with mental health services [13].

Psychosomatic disorders, which are physical symptoms arising from psychological factors, are particularly prevalent among adolescents. These disorders often complicate the understanding and management of mental health issues due to their dual nature [4]. Furthermore, childhood trauma is another significant factor influencing adolescents’ mental health literacy. The long-term psychosomatic effects of childhood trauma underscore the importance of early intervention and trauma-informed care [14]. Moreover, mental toughness and subjective well-being are interrelated constructs that also impact adolescents’ mental health literacy. Higher levels of mental toughness are associated with better coping strategies and overall well-being, highlighting the need for interventions that build resilience and mental toughness among adolescents [15]. Family functioning, optimism, and resilience are crucial predictors of psychological well-being, emphasizing the interconnectedness of these factors in promoting mental health [16].

The influence of globalization, cultural narratives, and family systems on mental health literacy cannot be overstated. These factors shape adolescents’ perceptions and beliefs about mental health, impacting their willingness to seek help and engage in preventive behaviors [17, 18]. Recent research has underscored the importance of systemic factors in improving mental health literacy among adolescents. Factors, such as family communication patterns, cognitive flexibility, and media literacy significantly impact adolescents’ mental health outcomes [3, 7]. Moreover, the role of community support and the broader social environment is also critical. Community programs, peer support groups, and local organizations provide essential resources and support for adolescents, promoting mental health literacy and reducing stigma [19]. The findings of this study are situated within the broader context of existing literature on adolescent mental health literacy. Previous research has highlighted the significant gaps in mental health knowledge and the pervasive stigma associated with mental health issues among adolescents [20, 21]. Interventions targeting these gaps, such as school-based mental health promotion programs and peer-led initiatives, have shown promise in improving mental health outcomes [22, 23].

This study is guided by the health belief model (HBM), which is widely used to understand health-related behaviors, including mental health literacy. The HBM posits that individuals’ beliefs about health problems, perceived benefits of action, and barriers to action can predict health-related behaviors [4, 15, 24, 25]. The model includes several key components, including perceived susceptibility, which refers to adolescents’ beliefs about their risk of developing mental health issues, perceived severity, which involves beliefs about the seriousness of mental health problems and their potential consequences, perceived benefits, which are beliefs about the effectiveness of taking preventive actions or seeking treatment, perceived barriers, which include perceived obstacles that hinder seeking help or engaging in preventive behaviors, cues to action, which are factors that trigger the decision-making process to seek help or adopt health-promoting behaviors, and self-efficacy, which is the confidence in one’s ability to take action and manage mental health issues [26-29].

Understanding adolescents’ mental health literacy is crucial for promoting mental health and well-being. By examining the factors influencing mental health literacy, including family dynamics, cultural beliefs, educational settings, and systemic factors, this study aimed to contribute to the development of effective mental health interventions. Thus, the current study aimed to build on this existing knowledge by exploring the specific knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of adolescents in Richmond Hill, Ontario.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study employed semi-structured interviews to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding mental health literacy among adolescents. The study was conducted from April to July 2023, to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the subject through in-depth participant insights.

Participants

The study focused on adolescents aged 13 to 18 from Richmond Hill, Ontario, selected using purposive sampling to ensure a diverse sample in terms of age, gender, and socioeconomic background. Participants, all secondary school students, provided informed consent. The consent process included an information session at their school, where the study’s objectives, methods, risks, and benefits were explained. Detailed information sheets were given to participants and their parents or guardians, emphasizing voluntary participation, confidentiality, and contact information for inquiries. Consent forms, signed by both participants and a parent or guardian (for those under 18), reiterated study details and the right to withdraw. Before each interview, researchers reviewed the consent form with participants to ensure full understanding. Data collection continued until theoretical saturation was reached, ending after 29 interviews when no new themes emerged.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, providing flexibility while ensuring all relevant topics were covered. Interviewers received rigorous training to ensure consistency and effective interviewing techniques. The interview guide was refined through pilot testing with adolescents outside the main study. During interviews, rapport was built with general questions, creating a comfortable atmosphere, and interviewers adapted questions based on participants’ responses. This approach allowed in-depth exploration of participants’ mental health literacy.

Interviews were conducted in person, lasting 45 to 60 minutes, focusing on three main areas: Knowledge of mental health and services, attitudes toward mental health, and beliefs about the causes and consequences of mental health issues. Open-ended questions were as follows:

“Can you describe what comes to mind when you hear the term ‘mental health?”

“What are some common mental health issues you are aware of?”

“Where do you get most of your information about mental health?”

“How do you think mental health issues can affect a person’s life?”

Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent using high-quality digital devices to ensure clarity. As a precaution, a secondary recording device was used. Participants were assured of confidentiality, and the recordings were stored securely in encrypted formats. Identifying information was anonymized during transcription, and access to transcripts was restricted to the research team.

Data analysis was conducted using NVivo software and thematic analysis. Rigorous measures, including inter-coder reliability checks and member checking, were implemented to ensure reliability. Researchers independently coded transcripts and resolved discrepancies through consensus, refining the coding scheme. Preliminary findings were validated with participants, and triangulation was used to corroborate findings with other sources.

The analysis involved several steps: Initial coding to identify significant statements, categorization of codes into major themes, and iterative theme development. Researchers maintained objectivity by engaging in reflexive practices, such as keeping reflective journals and conducting debriefing sessions, to mitigate personal biases. The diverse backgrounds of the research team helped challenge and refine interpretations. By being transparent about their positionality and minimizing biases, the researchers aimed to accurately represent participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Results

The participants were adolescents residing in Richmond Hill, Ontario. The study included a total of 29 adolescents from Richmond Hill, Ontario, to ensure a diverse representation of demographic backgrounds. The participants ranged in age from 13 to 18 years old. Of the 29 participants, 14 were female (48.3%), 13 were male (44.8%), and two cases were identified as non-binary (6.9%). The socioeconomic background of participants varied, with ten (34.5%) coming from low-income households, 12(41.4%) from middle-income households, and seven (24.1%) from high-income households. Ethnic diversity was also represented, with 15 participants identifying as Caucasian (51.7%), six as Asian (20.7%), four as African-Canadian (13.8%), and four as Hispanic (13.8%). Additionally, 18 participants (62.1%) were attending public schools, while 11(37.9%) were attending private schools.

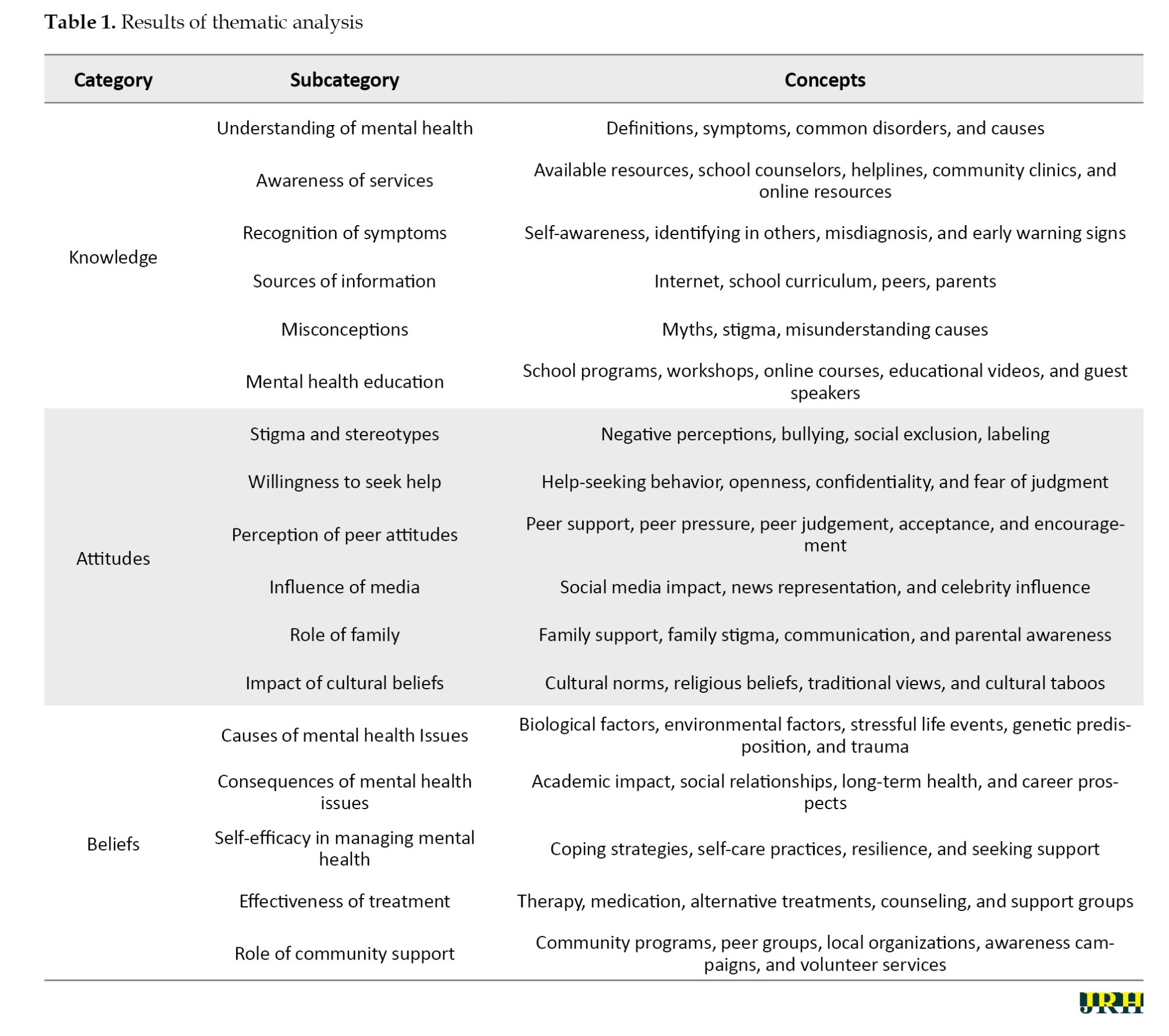

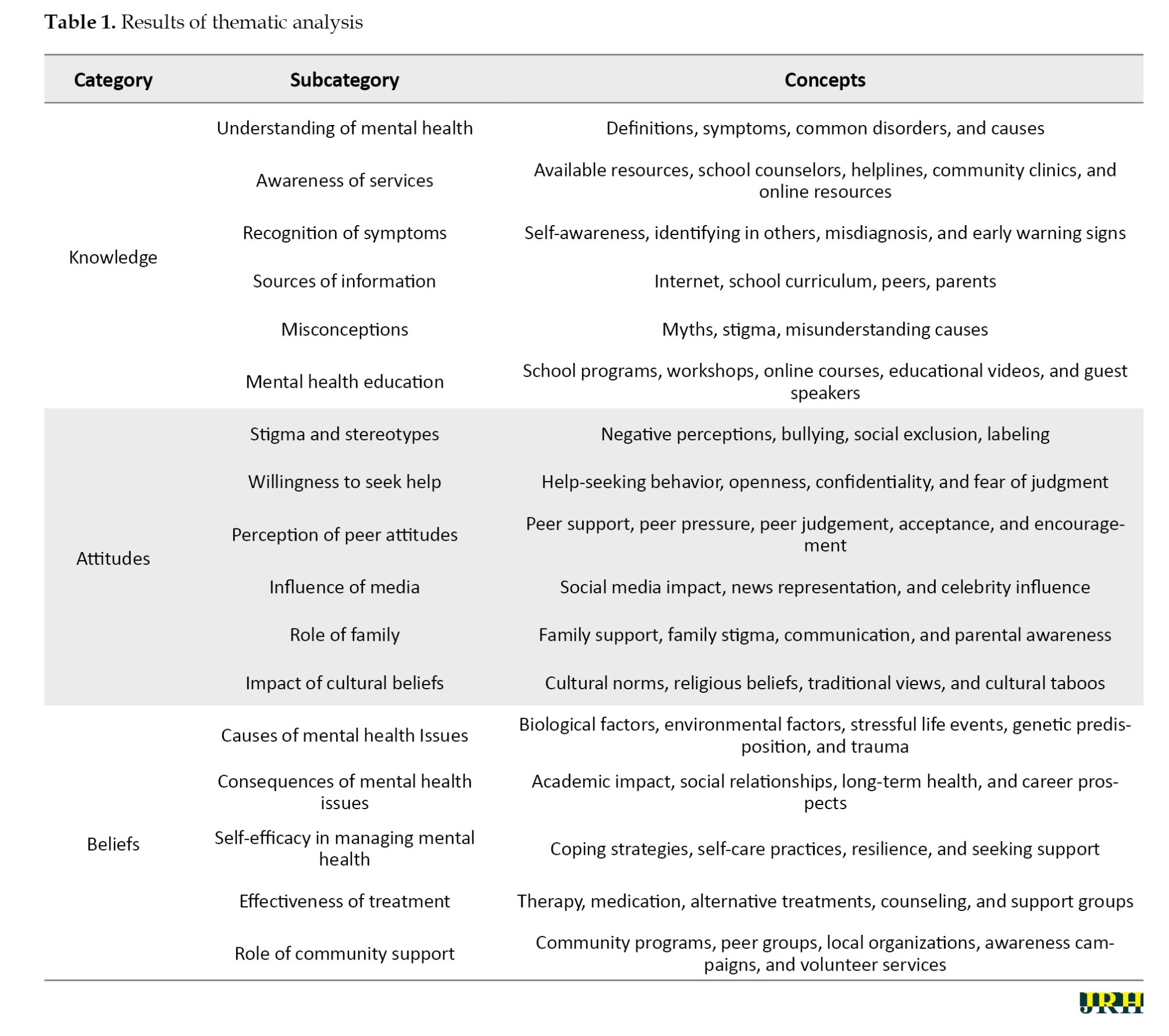

The data analysis of the semi-structured interviews revealed three main themes: Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding mental health literacy among adolescents. Each theme comprised several subthemes and associated concepts, providing a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ perspectives.

Knowledge

Adolescents demonstrated varying degrees of understanding and awareness related to mental health. This theme was divided into several subthemes (Table 1):

1. Understanding of mental health

• Concepts: Definitions, symptoms, common disorders, causes

• Quotations:

“Mental health to me is about how we feel, think, and act. It’s like mental wellness.”

“I know anxiety and depression are common, but I’m not sure about others.”

2. Awareness of services

• Concepts: Available resources, school counselors, helplines, community clinics, online resources

• Quotations:

“We have a school counselor, but I don’t know how to approach them.”

“I’ve seen online helplines but never used one.”

3. Recognition of symptoms

• Concepts: Self-awareness, identifying in others, misdiagnosis, early warning signs

• Quotations:

“Sometimes I feel anxious, but I don’t know if it’s serious.”

“It’s hard to tell if a friend is just sad or depressed.”

4. Sources of information

• Concepts: Internet, school curriculum, peers, parents

• Quotations:

“I mostly learn about mental health from social media.”

“Our health class talked a bit about mental health, but not much.”

5. Misconceptions

• Concepts: Myths, stigma, misunderstanding causes

• Quotations:

“Some people think mental health issues mean you’re weak.”

“There are still lots of wrong ideas about why people get depressed.”

6. Mental health education

• Concepts: School programs, workshops, online courses, educational videos, guest speakers

• Quotations:

“We need more programs in school that talk about mental health openly.”

“Workshops and guest speakers can help us understand better.”

Attitudes

The participants’ attitudes toward mental health varied significantly, revealing insights into stigma, willingness to seek help, and the influence of peers and media.

1. Stigma and stereotypes

• Concepts: Negative perceptions, bullying, social exclusion, labeling

• Quotations:

“People still get bullied if they talk about their mental health issues.”

“There’s a lot of labeling, like calling someone ‘crazy’.”

2. Willingness to seek help

• Concepts: Help-seeking behavior, openness, confidentiality, fear of judgment

• Quotations:

“I would be scared to tell someone because they might judge me.”

“Confidentiality is important. I don’t want everyone to know my issues.”

3. Perception of peer attitudes

• Concepts: Peer support, peer pressure, peer judgment, acceptance, encouragement

• Quotations:

“Having supportive friends makes it easier to talk about mental health.”

“There’s a lot of peer pressure to act like everything is okay.”

4. Influence of media

• Concepts: Social media impact, news representation, celebrity influence

• Quotations:

“Social media can be both helpful and harmful for mental health awareness.”

“Celebrities talking about their mental health helps normalize it.”

5. Role of family

• Concepts: Family support, family stigma, communication, parental awareness

• Quotations:

“My family supports me, but I know others who aren’t as lucky.”

“Some parents still think mental health issues aren’t real.”

6. Impact of cultural beliefs

• Concepts: Cultural norms, religious beliefs, traditional views, cultural taboos

• Quotations:

“In my culture, talking about mental health is a taboo.”

“Religious beliefs can sometimes clash with mental health treatment.”

Beliefs

Adolescents hold various beliefs regarding the causes, consequences, and management of mental health issues.

1. Causes of mental health issues

• Concepts: Biological factors, environmental factors, stressful life events, genetic predisposition, trauma

• Quotations:

“I think mental health issues can be inherited.”

“Stress from school and life events definitely play a role.”

2. Consequences of mental health issues

• Concepts: Academic impact, social relationships, long-term health, career prospects

• Quotations:

“Mental health problems can really affect your grades.”

“It’s hard to maintain friendships when you’re struggling mentally.”

3. Self-efficacy in managing mental health

• Concepts: Coping strategies, self-care practices, resilience, seeking support

• Quotations:

“I practice mindfulness to help manage my anxiety.”

“Knowing when to seek help is part of taking care of yourself.”

4. Effectiveness of treatment

• Concepts: Therapy, medication, alternative treatments, counseling, support groups

• Quotations:

“Therapy works, but it’s not always accessible.”

“I’ve heard mixed things about medication.”

5. Role of community support

• Concepts: Community programs, peer groups, local organizations, awareness campaigns, volunteer services

• Quotations:

“Community programs can be a lifeline for many.”

“Being part of a support group made a big difference for me.”

Discussion

The study revealed that adolescents had a basic understanding of mental health but also harbored several misconceptions. Participants were aware of common mental health disorders, like anxiety and depression but had limited knowledge of other disorders and the causes of mental health issues. This aligns with previous research indicating that while adolescents often recognize common mental health conditions, their overall mental health literacy remains limited [5]. The reliance on internet sources and peers for information underscores the need for more structured and accurate mental health education in schools [20].

Moreover, the awareness of available mental health services was variable. While some participants knew about school counselors and online resources, others were unaware or uncertain about how to access these services. This inconsistency in knowledge about mental health resources underscores the importance of clear communication and education about available support services [10]. Enhancing adolescents’ awareness of mental health services can improve help-seeking behaviors and early intervention [30].

Stigma emerged as a significant barrier to mental health literacy and help-seeking among adolescents. Participants expressed concerns about being judged or labeled if they disclosed their mental health issues. This finding is consistent with previous studies that highlight the stigma associated with mental health problems as a major obstacle to seeking help [12, 13]. Addressing stigma through education and awareness campaigns is crucial to fostering a more supportive environment for adolescents to discuss and seek help for their mental health concerns [4, 8, 31, 32].

The willingness to seek help was influenced by several factors, including fear of judgment, confidentiality concerns, and the perception of peer attitudes. Adolescents reported being more likely to seek help if they believed their confidentiality would be maintained and if they received support from peers. This aligns with research showing that adolescents’ help-seeking behaviors are significantly influenced by their perceptions of peer support and confidentiality [11, 33].

Family dynamics also played a crucial role in shaping adolescents’ attitudes toward mental health. Supportive family environments facilitated open discussions about mental health, while families with stigmatizing attitudes hindered such conversations. This is consistent with findings that emphasize the role of family communication patterns in influencing mental health literacy and help-seeking behaviors [18, 34]. Encouraging open and supportive family discussions about mental health can enhance adolescents’ willingness to seek help and improve their mental health outcomes.

Cultural beliefs and norms significantly impacted adolescents’ perceptions of mental health. Participants from different cultural backgrounds reported varying levels of stigma and acceptance of mental health issues. Cultural narratives often dictate the extent to which mental health is openly discussed and accepted, with some cultures viewing mental health issues as taboo [8, 9]. Understanding these cultural influences is essential for developing culturally sensitive mental health interventions that resonate with diverse adolescent populations.

Adolescents’ beliefs about the causes of mental health issues varied, with some attributing them to biological factors and others to environmental stressors. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that adolescents often have diverse and sometimes conflicting beliefs about the origins of mental health problems [4]. Educating adolescents about the multifactorial nature of mental health issues can help in demystifying these conditions and promoting a more comprehensive understanding.

The consequences of mental health issues were also a significant concern for participants. Many adolescents recognized the negative impact of mental health problems on academic performance, social relationships, and long-term health. This is consistent with studies highlighting the broad and pervasive effects of mental health issues on various aspects of adolescents’ lives [14, 35]. Addressing these concerns through supportive educational and community programs can mitigate the adverse effects and enhance adolescents’ overall well-being.

Beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment varied, with some adolescents expressing confidence in therapy and medication while others were skeptical about these interventions. This mixed perception is reflected in existing literature, which shows that adolescents’ beliefs about treatment effectiveness are influenced by personal experiences, cultural norms, and the quality of information they receive [8, 9, 18, 19, 36-39]. The study contributes to existing knowledge by highlighting the specific gaps in mental health literacy among adolescents and emphasizing the role of family dynamics, cultural beliefs, and peer influence in shaping attitudes toward mental health. It supports previous findings that stigma and lack of accurate information are major barriers to help-seeking behaviors. Novel insights from this study include the identification of unique cultural factors that influence adolescents’ mental health literacy and the importance of community support in promoting mental health awareness.

The role of community support was highlighted as crucial for promoting mental health literacy. Participants emphasized the importance of community programs, peer support groups, and local organizations in providing resources and support for mental health. This finding supports the notion that community-based interventions can play a significant role in enhancing mental health literacy and reducing stigma [22, 23]. Strengthening community support networks can create a more inclusive and supportive environment for adolescents to address their mental health needs.

The findings of this study have several implications for practice and policy. First, there is a need for comprehensive mental health education programs in schools that provide accurate information about mental health disorders, symptoms, and available services. These programs should be designed to address common misconceptions and promote a supportive environment for discussing mental health issues [10, 20]. Second, efforts to reduce stigma should be a central component of mental health literacy initiatives. Education and awareness campaigns that involve both adolescents and their families can help in normalizing mental health discussions and reducing the stigma associated with seeking help [5, 33]. Third, culturally sensitive interventions are essential to address the diverse needs of adolescents from different backgrounds. Understanding and incorporating cultural beliefs and norms into mental health programs can enhance their effectiveness and ensure that they resonate with the target population [8, 9]. Fourth, community-based support systems should be strengthened to provide accessible and comprehensive mental health resources. Collaborations between schools, community organizations, and mental health professionals can create a robust support network that facilitates early intervention and ongoing support for adolescents [22, 23].

Collaboration between mental health professionals and schools to offer accessible counseling services and create peer support groups is vital [32, 40-42]. Culturally sensitive programs considering diverse adolescent backgrounds ensure inclusivity and effectiveness. Implementing these strategies can enhance mental health literacy, promote early intervention, and improve mental health outcomes among adolescents [39].

Conclusion

Findings indicated that while adolescents have a basic understanding of mental health, they lack knowledge about less common disorders and the causes of mental health issues. Misconceptions and stigma are widespread, affecting their willingness to seek help. Family dynamics, cultural beliefs, and peer influence significantly shape their attitudes toward mental health. Awareness and perceived effectiveness of mental health services varied, with community support identified as crucial for promoting mental health literacy.

The study emphasizes the need for comprehensive, culturally sensitive mental health education for adolescents. Addressing misconceptions, reducing stigma, and enhancing support systems are vital for improving mental health literacy and outcomes. By fostering supportive environments in families, schools, and communities, adolescents can be better equipped to recognize, manage, and seek help for mental health issues, promoting overall well-being.

In practice, comprehensive school-based mental health education programs are needed to address knowledge gaps and misconceptions. These programs should reduce stigma and encourage open discussions. Training educators and school counselors to identify and support students with mental health issues is essential. Community-based initiatives involving families and local resources can provide additional support, fostering an inclusive environment for adolescents. Policymakers should use these findings to develop responsive mental health policies and allocate resources effectively.

Strategies to improve mental health literacy include integrating mental health education into school curriculums, providing accurate information, debunking myths, and training teachers and counselors to recognize and support mental health issues. Schools can organize interactive workshops and invite guest speakers. Public awareness campaigns targeting adolescents and their families can reduce stigma and promote open discussions about mental health.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small and limited to adolescents in Richmond Hill, Ontario, which may not be representative of broader populations. The use of semi-structured interviews, while providing in-depth insights, may also introduce interviewer bias. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data, which can be influenced by social desirability bias. Methodological limitations, such as these might impact the interpretation of the results. Discrepancies in findings could be due to the specific characteristics of the sample, including demographic factors and the local cultural context. For example, the diverse cultural backgrounds of participants might have influenced their perceptions and attitudes toward mental health, leading to variations in the data. Furthermore, contextual factors, such as the availability of mental health resources in Richmond Hill, might have shaped participants’ experiences and knowledge.

Recommendation for future studies

Future research should incorporate larger, more diverse samples to enhance generalizability and utilize longitudinal studies to track the evolution of mental health literacy and the long-term effects of educational interventions. It is crucial to investigate barriers to accessing mental health services and develop effective strategies to overcome them. Complementary quantitative studies can statistically validate trends observed in qualitative research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines set forth by the KMAN Research Institute, Richmond Hill, Canada (Code: KEC.2023.12C1). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and, where necessary, from their parents or guardians. Participants were assured of their confidentiality and anonymity, and they were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Valerie Karstensen; Methodology: Roodi Hooshmandi and Mathias Bastholm; Data collection: Roodi Hooshmandi; Data analysis: Valerie Karstensen and Mathias Bastholm; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all individuals who helped them to do the project.

References

Adolescence is a critical period characterized by significant physical, emotional, and social changes. It is during this time that mental health issues often first emerge, making it essential to understand and address the mental health literacy of this age group. Given the rising prevalence of mental health issues among adolescents, understanding their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs is crucial for improving mental health outcomes [1-3].

Adolescents face unique challenges in identifying and addressing mental health concerns due to various factors, including stigma, lack of information, and cultural influences [4]. The concept of mental health literacy, introduced by Burns and Rapee, refers to the knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders that aid their recognition, management, or prevention [5]. High levels of mental health literacy are associated with positive attitudes toward seeking help and better mental health outcomes [6]. However, adolescents often display significant gaps in mental health literacy, which can lead to delayed help-seeking and poorer mental health outcomes [6]. Conversely, dysfunctional family communication patterns can negatively impact adolescents’ mental health literacy and overall well-being [7]. Moreover, cultural narratives and traditions significantly influence family mental health, often dictating the stigmatization or acceptance of mental health issues [8]. Understanding these gaps and addressing them through targeted interventions is critical.

Globalization has further complicated the influence of family traditions and values on adolescents’ mental health literacy. As cultural norms evolve, the clash between traditional values and modern mental health perspectives can create confusion and hinder effective communication about mental health [9]. Understanding these cultural influences is crucial for developing culturally sensitive mental health interventions.

Educational settings also play a pivotal role in shaping mental health literacy. School-based mental health promotion programs have shown effectiveness in improving mental health knowledge and attitudes among adolescents [10]. However, the success of these programs often depends on the context and the extent to which they address the specific needs and concerns of adolescents. Peer-led interventions have also been highlighted as effective in low-resource settings, emphasizing the importance of peer influence in shaping mental health behaviors [11].

Adolescents’ experiences with mental health services reveal critical insights into their perceptions and barriers to accessing care. Studies have shown that adolescents often perceive mental health services as stigmatizing and taboo, which discourages them from seeking help [12]. Additionally, the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the perceived effectiveness of mental health interventions significantly influence adolescents’ willingness to engage with mental health services [13].

Psychosomatic disorders, which are physical symptoms arising from psychological factors, are particularly prevalent among adolescents. These disorders often complicate the understanding and management of mental health issues due to their dual nature [4]. Furthermore, childhood trauma is another significant factor influencing adolescents’ mental health literacy. The long-term psychosomatic effects of childhood trauma underscore the importance of early intervention and trauma-informed care [14]. Moreover, mental toughness and subjective well-being are interrelated constructs that also impact adolescents’ mental health literacy. Higher levels of mental toughness are associated with better coping strategies and overall well-being, highlighting the need for interventions that build resilience and mental toughness among adolescents [15]. Family functioning, optimism, and resilience are crucial predictors of psychological well-being, emphasizing the interconnectedness of these factors in promoting mental health [16].

The influence of globalization, cultural narratives, and family systems on mental health literacy cannot be overstated. These factors shape adolescents’ perceptions and beliefs about mental health, impacting their willingness to seek help and engage in preventive behaviors [17, 18]. Recent research has underscored the importance of systemic factors in improving mental health literacy among adolescents. Factors, such as family communication patterns, cognitive flexibility, and media literacy significantly impact adolescents’ mental health outcomes [3, 7]. Moreover, the role of community support and the broader social environment is also critical. Community programs, peer support groups, and local organizations provide essential resources and support for adolescents, promoting mental health literacy and reducing stigma [19]. The findings of this study are situated within the broader context of existing literature on adolescent mental health literacy. Previous research has highlighted the significant gaps in mental health knowledge and the pervasive stigma associated with mental health issues among adolescents [20, 21]. Interventions targeting these gaps, such as school-based mental health promotion programs and peer-led initiatives, have shown promise in improving mental health outcomes [22, 23].

This study is guided by the health belief model (HBM), which is widely used to understand health-related behaviors, including mental health literacy. The HBM posits that individuals’ beliefs about health problems, perceived benefits of action, and barriers to action can predict health-related behaviors [4, 15, 24, 25]. The model includes several key components, including perceived susceptibility, which refers to adolescents’ beliefs about their risk of developing mental health issues, perceived severity, which involves beliefs about the seriousness of mental health problems and their potential consequences, perceived benefits, which are beliefs about the effectiveness of taking preventive actions or seeking treatment, perceived barriers, which include perceived obstacles that hinder seeking help or engaging in preventive behaviors, cues to action, which are factors that trigger the decision-making process to seek help or adopt health-promoting behaviors, and self-efficacy, which is the confidence in one’s ability to take action and manage mental health issues [26-29].

Understanding adolescents’ mental health literacy is crucial for promoting mental health and well-being. By examining the factors influencing mental health literacy, including family dynamics, cultural beliefs, educational settings, and systemic factors, this study aimed to contribute to the development of effective mental health interventions. Thus, the current study aimed to build on this existing knowledge by exploring the specific knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of adolescents in Richmond Hill, Ontario.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study employed semi-structured interviews to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding mental health literacy among adolescents. The study was conducted from April to July 2023, to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the subject through in-depth participant insights.

Participants

The study focused on adolescents aged 13 to 18 from Richmond Hill, Ontario, selected using purposive sampling to ensure a diverse sample in terms of age, gender, and socioeconomic background. Participants, all secondary school students, provided informed consent. The consent process included an information session at their school, where the study’s objectives, methods, risks, and benefits were explained. Detailed information sheets were given to participants and their parents or guardians, emphasizing voluntary participation, confidentiality, and contact information for inquiries. Consent forms, signed by both participants and a parent or guardian (for those under 18), reiterated study details and the right to withdraw. Before each interview, researchers reviewed the consent form with participants to ensure full understanding. Data collection continued until theoretical saturation was reached, ending after 29 interviews when no new themes emerged.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, providing flexibility while ensuring all relevant topics were covered. Interviewers received rigorous training to ensure consistency and effective interviewing techniques. The interview guide was refined through pilot testing with adolescents outside the main study. During interviews, rapport was built with general questions, creating a comfortable atmosphere, and interviewers adapted questions based on participants’ responses. This approach allowed in-depth exploration of participants’ mental health literacy.

Interviews were conducted in person, lasting 45 to 60 minutes, focusing on three main areas: Knowledge of mental health and services, attitudes toward mental health, and beliefs about the causes and consequences of mental health issues. Open-ended questions were as follows:

“Can you describe what comes to mind when you hear the term ‘mental health?”

“What are some common mental health issues you are aware of?”

“Where do you get most of your information about mental health?”

“How do you think mental health issues can affect a person’s life?”

Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent using high-quality digital devices to ensure clarity. As a precaution, a secondary recording device was used. Participants were assured of confidentiality, and the recordings were stored securely in encrypted formats. Identifying information was anonymized during transcription, and access to transcripts was restricted to the research team.

Data analysis was conducted using NVivo software and thematic analysis. Rigorous measures, including inter-coder reliability checks and member checking, were implemented to ensure reliability. Researchers independently coded transcripts and resolved discrepancies through consensus, refining the coding scheme. Preliminary findings were validated with participants, and triangulation was used to corroborate findings with other sources.

The analysis involved several steps: Initial coding to identify significant statements, categorization of codes into major themes, and iterative theme development. Researchers maintained objectivity by engaging in reflexive practices, such as keeping reflective journals and conducting debriefing sessions, to mitigate personal biases. The diverse backgrounds of the research team helped challenge and refine interpretations. By being transparent about their positionality and minimizing biases, the researchers aimed to accurately represent participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Results

The participants were adolescents residing in Richmond Hill, Ontario. The study included a total of 29 adolescents from Richmond Hill, Ontario, to ensure a diverse representation of demographic backgrounds. The participants ranged in age from 13 to 18 years old. Of the 29 participants, 14 were female (48.3%), 13 were male (44.8%), and two cases were identified as non-binary (6.9%). The socioeconomic background of participants varied, with ten (34.5%) coming from low-income households, 12(41.4%) from middle-income households, and seven (24.1%) from high-income households. Ethnic diversity was also represented, with 15 participants identifying as Caucasian (51.7%), six as Asian (20.7%), four as African-Canadian (13.8%), and four as Hispanic (13.8%). Additionally, 18 participants (62.1%) were attending public schools, while 11(37.9%) were attending private schools.

The data analysis of the semi-structured interviews revealed three main themes: Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding mental health literacy among adolescents. Each theme comprised several subthemes and associated concepts, providing a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ perspectives.

Knowledge

Adolescents demonstrated varying degrees of understanding and awareness related to mental health. This theme was divided into several subthemes (Table 1):

1. Understanding of mental health

• Concepts: Definitions, symptoms, common disorders, causes

• Quotations:

“Mental health to me is about how we feel, think, and act. It’s like mental wellness.”

“I know anxiety and depression are common, but I’m not sure about others.”

2. Awareness of services

• Concepts: Available resources, school counselors, helplines, community clinics, online resources

• Quotations:

“We have a school counselor, but I don’t know how to approach them.”

“I’ve seen online helplines but never used one.”

3. Recognition of symptoms

• Concepts: Self-awareness, identifying in others, misdiagnosis, early warning signs

• Quotations:

“Sometimes I feel anxious, but I don’t know if it’s serious.”

“It’s hard to tell if a friend is just sad or depressed.”

4. Sources of information

• Concepts: Internet, school curriculum, peers, parents

• Quotations:

“I mostly learn about mental health from social media.”

“Our health class talked a bit about mental health, but not much.”

5. Misconceptions

• Concepts: Myths, stigma, misunderstanding causes

• Quotations:

“Some people think mental health issues mean you’re weak.”

“There are still lots of wrong ideas about why people get depressed.”

6. Mental health education

• Concepts: School programs, workshops, online courses, educational videos, guest speakers

• Quotations:

“We need more programs in school that talk about mental health openly.”

“Workshops and guest speakers can help us understand better.”

Attitudes

The participants’ attitudes toward mental health varied significantly, revealing insights into stigma, willingness to seek help, and the influence of peers and media.

1. Stigma and stereotypes

• Concepts: Negative perceptions, bullying, social exclusion, labeling

• Quotations:

“People still get bullied if they talk about their mental health issues.”

“There’s a lot of labeling, like calling someone ‘crazy’.”

2. Willingness to seek help

• Concepts: Help-seeking behavior, openness, confidentiality, fear of judgment

• Quotations:

“I would be scared to tell someone because they might judge me.”

“Confidentiality is important. I don’t want everyone to know my issues.”

3. Perception of peer attitudes

• Concepts: Peer support, peer pressure, peer judgment, acceptance, encouragement

• Quotations:

“Having supportive friends makes it easier to talk about mental health.”

“There’s a lot of peer pressure to act like everything is okay.”

4. Influence of media

• Concepts: Social media impact, news representation, celebrity influence

• Quotations:

“Social media can be both helpful and harmful for mental health awareness.”

“Celebrities talking about their mental health helps normalize it.”

5. Role of family

• Concepts: Family support, family stigma, communication, parental awareness

• Quotations:

“My family supports me, but I know others who aren’t as lucky.”

“Some parents still think mental health issues aren’t real.”

6. Impact of cultural beliefs

• Concepts: Cultural norms, religious beliefs, traditional views, cultural taboos

• Quotations:

“In my culture, talking about mental health is a taboo.”

“Religious beliefs can sometimes clash with mental health treatment.”

Beliefs

Adolescents hold various beliefs regarding the causes, consequences, and management of mental health issues.

1. Causes of mental health issues

• Concepts: Biological factors, environmental factors, stressful life events, genetic predisposition, trauma

• Quotations:

“I think mental health issues can be inherited.”

“Stress from school and life events definitely play a role.”

2. Consequences of mental health issues

• Concepts: Academic impact, social relationships, long-term health, career prospects

• Quotations:

“Mental health problems can really affect your grades.”

“It’s hard to maintain friendships when you’re struggling mentally.”

3. Self-efficacy in managing mental health

• Concepts: Coping strategies, self-care practices, resilience, seeking support

• Quotations:

“I practice mindfulness to help manage my anxiety.”

“Knowing when to seek help is part of taking care of yourself.”

4. Effectiveness of treatment

• Concepts: Therapy, medication, alternative treatments, counseling, support groups

• Quotations:

“Therapy works, but it’s not always accessible.”

“I’ve heard mixed things about medication.”

5. Role of community support

• Concepts: Community programs, peer groups, local organizations, awareness campaigns, volunteer services

• Quotations:

“Community programs can be a lifeline for many.”

“Being part of a support group made a big difference for me.”

Discussion

The study revealed that adolescents had a basic understanding of mental health but also harbored several misconceptions. Participants were aware of common mental health disorders, like anxiety and depression but had limited knowledge of other disorders and the causes of mental health issues. This aligns with previous research indicating that while adolescents often recognize common mental health conditions, their overall mental health literacy remains limited [5]. The reliance on internet sources and peers for information underscores the need for more structured and accurate mental health education in schools [20].

Moreover, the awareness of available mental health services was variable. While some participants knew about school counselors and online resources, others were unaware or uncertain about how to access these services. This inconsistency in knowledge about mental health resources underscores the importance of clear communication and education about available support services [10]. Enhancing adolescents’ awareness of mental health services can improve help-seeking behaviors and early intervention [30].

Stigma emerged as a significant barrier to mental health literacy and help-seeking among adolescents. Participants expressed concerns about being judged or labeled if they disclosed their mental health issues. This finding is consistent with previous studies that highlight the stigma associated with mental health problems as a major obstacle to seeking help [12, 13]. Addressing stigma through education and awareness campaigns is crucial to fostering a more supportive environment for adolescents to discuss and seek help for their mental health concerns [4, 8, 31, 32].

The willingness to seek help was influenced by several factors, including fear of judgment, confidentiality concerns, and the perception of peer attitudes. Adolescents reported being more likely to seek help if they believed their confidentiality would be maintained and if they received support from peers. This aligns with research showing that adolescents’ help-seeking behaviors are significantly influenced by their perceptions of peer support and confidentiality [11, 33].

Family dynamics also played a crucial role in shaping adolescents’ attitudes toward mental health. Supportive family environments facilitated open discussions about mental health, while families with stigmatizing attitudes hindered such conversations. This is consistent with findings that emphasize the role of family communication patterns in influencing mental health literacy and help-seeking behaviors [18, 34]. Encouraging open and supportive family discussions about mental health can enhance adolescents’ willingness to seek help and improve their mental health outcomes.

Cultural beliefs and norms significantly impacted adolescents’ perceptions of mental health. Participants from different cultural backgrounds reported varying levels of stigma and acceptance of mental health issues. Cultural narratives often dictate the extent to which mental health is openly discussed and accepted, with some cultures viewing mental health issues as taboo [8, 9]. Understanding these cultural influences is essential for developing culturally sensitive mental health interventions that resonate with diverse adolescent populations.

Adolescents’ beliefs about the causes of mental health issues varied, with some attributing them to biological factors and others to environmental stressors. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that adolescents often have diverse and sometimes conflicting beliefs about the origins of mental health problems [4]. Educating adolescents about the multifactorial nature of mental health issues can help in demystifying these conditions and promoting a more comprehensive understanding.

The consequences of mental health issues were also a significant concern for participants. Many adolescents recognized the negative impact of mental health problems on academic performance, social relationships, and long-term health. This is consistent with studies highlighting the broad and pervasive effects of mental health issues on various aspects of adolescents’ lives [14, 35]. Addressing these concerns through supportive educational and community programs can mitigate the adverse effects and enhance adolescents’ overall well-being.

Beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment varied, with some adolescents expressing confidence in therapy and medication while others were skeptical about these interventions. This mixed perception is reflected in existing literature, which shows that adolescents’ beliefs about treatment effectiveness are influenced by personal experiences, cultural norms, and the quality of information they receive [8, 9, 18, 19, 36-39]. The study contributes to existing knowledge by highlighting the specific gaps in mental health literacy among adolescents and emphasizing the role of family dynamics, cultural beliefs, and peer influence in shaping attitudes toward mental health. It supports previous findings that stigma and lack of accurate information are major barriers to help-seeking behaviors. Novel insights from this study include the identification of unique cultural factors that influence adolescents’ mental health literacy and the importance of community support in promoting mental health awareness.

The role of community support was highlighted as crucial for promoting mental health literacy. Participants emphasized the importance of community programs, peer support groups, and local organizations in providing resources and support for mental health. This finding supports the notion that community-based interventions can play a significant role in enhancing mental health literacy and reducing stigma [22, 23]. Strengthening community support networks can create a more inclusive and supportive environment for adolescents to address their mental health needs.

The findings of this study have several implications for practice and policy. First, there is a need for comprehensive mental health education programs in schools that provide accurate information about mental health disorders, symptoms, and available services. These programs should be designed to address common misconceptions and promote a supportive environment for discussing mental health issues [10, 20]. Second, efforts to reduce stigma should be a central component of mental health literacy initiatives. Education and awareness campaigns that involve both adolescents and their families can help in normalizing mental health discussions and reducing the stigma associated with seeking help [5, 33]. Third, culturally sensitive interventions are essential to address the diverse needs of adolescents from different backgrounds. Understanding and incorporating cultural beliefs and norms into mental health programs can enhance their effectiveness and ensure that they resonate with the target population [8, 9]. Fourth, community-based support systems should be strengthened to provide accessible and comprehensive mental health resources. Collaborations between schools, community organizations, and mental health professionals can create a robust support network that facilitates early intervention and ongoing support for adolescents [22, 23].

Collaboration between mental health professionals and schools to offer accessible counseling services and create peer support groups is vital [32, 40-42]. Culturally sensitive programs considering diverse adolescent backgrounds ensure inclusivity and effectiveness. Implementing these strategies can enhance mental health literacy, promote early intervention, and improve mental health outcomes among adolescents [39].

Conclusion

Findings indicated that while adolescents have a basic understanding of mental health, they lack knowledge about less common disorders and the causes of mental health issues. Misconceptions and stigma are widespread, affecting their willingness to seek help. Family dynamics, cultural beliefs, and peer influence significantly shape their attitudes toward mental health. Awareness and perceived effectiveness of mental health services varied, with community support identified as crucial for promoting mental health literacy.

The study emphasizes the need for comprehensive, culturally sensitive mental health education for adolescents. Addressing misconceptions, reducing stigma, and enhancing support systems are vital for improving mental health literacy and outcomes. By fostering supportive environments in families, schools, and communities, adolescents can be better equipped to recognize, manage, and seek help for mental health issues, promoting overall well-being.

In practice, comprehensive school-based mental health education programs are needed to address knowledge gaps and misconceptions. These programs should reduce stigma and encourage open discussions. Training educators and school counselors to identify and support students with mental health issues is essential. Community-based initiatives involving families and local resources can provide additional support, fostering an inclusive environment for adolescents. Policymakers should use these findings to develop responsive mental health policies and allocate resources effectively.

Strategies to improve mental health literacy include integrating mental health education into school curriculums, providing accurate information, debunking myths, and training teachers and counselors to recognize and support mental health issues. Schools can organize interactive workshops and invite guest speakers. Public awareness campaigns targeting adolescents and their families can reduce stigma and promote open discussions about mental health.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small and limited to adolescents in Richmond Hill, Ontario, which may not be representative of broader populations. The use of semi-structured interviews, while providing in-depth insights, may also introduce interviewer bias. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data, which can be influenced by social desirability bias. Methodological limitations, such as these might impact the interpretation of the results. Discrepancies in findings could be due to the specific characteristics of the sample, including demographic factors and the local cultural context. For example, the diverse cultural backgrounds of participants might have influenced their perceptions and attitudes toward mental health, leading to variations in the data. Furthermore, contextual factors, such as the availability of mental health resources in Richmond Hill, might have shaped participants’ experiences and knowledge.

Recommendation for future studies

Future research should incorporate larger, more diverse samples to enhance generalizability and utilize longitudinal studies to track the evolution of mental health literacy and the long-term effects of educational interventions. It is crucial to investigate barriers to accessing mental health services and develop effective strategies to overcome them. Complementary quantitative studies can statistically validate trends observed in qualitative research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines set forth by the KMAN Research Institute, Richmond Hill, Canada (Code: KEC.2023.12C1). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and, where necessary, from their parents or guardians. Participants were assured of their confidentiality and anonymity, and they were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Valerie Karstensen; Methodology: Roodi Hooshmandi and Mathias Bastholm; Data collection: Roodi Hooshmandi; Data analysis: Valerie Karstensen and Mathias Bastholm; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all individuals who helped them to do the project.

References

- Heidari H, Doshman Ziari E, Barzegar N, Faghiharam B, Mehdizadeh AH. Designing an e-learning model for health tourism marketing case study: Educational healthcare centers of Islamic Azad University, Tehran. International Journal of Innovation Management and Organizational Behavior. 2024; 4(1):20-7. [DOI:10.61838/kman.ijimob.4.1.3]

- Rezvani SR, Abolghasemi S, Farhangi A. Presenting the model of self-care behaviors of pregnant women based on health literacy and mindfulness with the mediation of a health-oriented lifestyle. Applied Family Therapy Journal. 2022; 3(5):176-95. [DOI:10.61838/kman.aftj.3.5.11]

- Soleymani S, Mohammadkhani P, Zahrakar K. Developing a model of symptoms of nomophobia in students based on attachment style, media literacy and locus of control with the mediation of Internet addiction. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies. 2023; 4(3):83-96. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jayps.4.3.8]

- Bulut S, Bukhori B, Bhat RH. The Experience of Psychosomatic Disorders among Adolescents: Challenges and coping strategies. Journal of Personality and Psychosomatic Research. 2024; 2(2):19-25. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jppr.2.2.4]

- Burns JR, Rapee RM. Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people's knowledge of depression and help seeking.Journal of Adolescence. 2006; 29(2):225-39. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.05.004] [PMID]

- Mansfield R, Patalay P, Humphrey N. A systematic literature review of existing conceptualisation and measurement of mental health literacy in adolescent research: Current challenges and inconsistencies. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):607. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-08734-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Eshagh Neymvari N, Abolghasemi S, Hamzehpoor Haghighi T. Analysis of structural equations in the relationship between family communication patterns with tendency to critical thinking and students’ happiness with the mediating role of cognitive flexibility in students. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies. 2023; 4(1):49-60. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jayps.4.1.6]

- Bilač S, Öztop F, Kutuk Y, Karadag M. Cultural narratives and their impact on family mental health. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2024; 2(2):18-24. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.2.2.4]

- Herawati N, Jafari M, Sanders K. The influence of globalization on family traditions and values. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2024; 2(2):4-10. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.2.2.2]

- Lehner L, Gillé V, Baldofski S, Bauer S, Becker K, Diestelkamp S, et al. Moderators of pre-post changes in school-based mental health promotion: Psychological stress symptom decrease for adolescents with mental health problems, knowledge increase for all. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 13:899185. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.899185] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kavya P, Sonali D, Shumayla S, Rajesh S, Sunil M. Effectiveness of peer-led intervention on KAP related to sexual reproductive and mental health issues among adolescents in low resource settings India: A comparative study among participants and non-participants. Health. 2020; 12(09):1151-68. [DOI:10.4236/health.2020.129085]

- Tharaldsen KB, Stallard P, Cuijpers P, Bru E, Bjaastad JF. ‘It’s a bit taboo’: A qualitative study of norwegian adolescents’ perceptions of mental healthcare services. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2016; 22(2):111-26. [DOI:10.1080/13632752.2016.1248692]

- Shin S, Ahn S. Experience of adolescents in mental health inpatient units: A metasynthesis of qualitative evidence. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2023; 30(1):8-20. [DOI:10.1111/jpm.12836] [PMID]

- Saadati N, Kiliçaslan F, Salami MO. The psychosomatic effects of childhood trauma: Insights from adult survivors. Journal of Personality and Psychosomatic Research. 2024; 2(2):34-40. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jppr.2.2.6]

- Parsaiezadeh M, Shahbazimoghadam M, Derakhshande M, Namjoo M. Exploring the predictive relationship between mental toughness and subjective well-being: A quantitative analysis. Journal of Personality and Psychosomatic Research. 2024; 2(1):29-35. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jppr.2.1.6]

- Lotfnejadafshar S, Khakpour R, Dokanehi Fard F. Providing a structural model of psychological well-being prediction based on family functioning, optimism, and resilience mediated by social adequacy. Applied Family Therapy Journal. 2022; 3(1):89-109. [DOI:10.61838/kman.aftj.3.1.6]

- Yang J, McDonnell M. Social structures and family systems: An analysis of cultural influences. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2024; 2(1):31-41. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.2.1.6]

- Zadhasan Z. Communication within families: Understanding patterns and impacts on mental health. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2023; 1(2):5-13. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.1.2.2]

- Nobre J, Luis H, Oliveira AP, Monteiro F, Cordeiro R, Sequeira C, et al. Psychological vulnerability indices and the adolescent's good mental health factors: A correlational study in a sample of portuguese adolescents. Children. 2022; 9(12):1961. [DOI:10.3390/children9121961] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bjørnsen HN, Espnes GA, Eilertsen MB, Ringdal R, Moksnes UK. The relationship between positive mental health literacy and mental well-being among adolescents: Implications for school health services. The Journal of School Nursing. 2019; 35(2):107-16. [DOI:10.1177/1059840517732125] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kaiser RB, LeBreton JM, Hogan J. The dark side of personality and extreme leader behavior. Applied Psychology. 2015; 64(1):55-92. [DOI:10.1111/apps.12024]

- Simkiss NJ, Gray NS, Malone G, Kemp A, Snowden RJ. Improving mental health literacy in year 9 high school children across wales: A protocol for a randomised control treatment trial (RCT) of a mental health literacy programme across an entire country. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):727. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-08736-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vella SA, Swann C, Batterham M, Boydell KM, Eckermann S, Fogarty A, et al. Ahead of the game protocol: A multi-component, community sport-based program targeting prevention, promotion and early intervention for mental health among adolescent males. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18(1):390. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-018-5319-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Majlessi Koupaei H, Farista R. Psychological pathways to immunity: The role of emotions and stress in health and disease. Journal of Personality and Psychosomatic Research. 2024; 2(1):1-3. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jppr.2.1.1]

- Ofem UJ. Adjustment tendencies among transiting students: A mediation analysis using psychological wellbeing indices. International Journal of Education and Cognitive Sciences. 2023; 4(3):1-19. [DOI:10.61838/kman.ijecs.4.3.1]

- Golparvar M, Parsakia K. Building resilience: Psychological approaches to prevent burnout in health professionals. KMAN Counseling & Psychology Nexus. 2023; 1(1):159-66. [DOI:10.61838/kman.psychnexus.1.1.18]

- Karimi Dastaki A, Mahmudi M. [The effectiveness of life meaning workshops on resilience, negative affect, and perceived social support in students (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Dynamics in Mood Disorders. 2024; 3(1):187-97. [DOI:10.61838/kman.pdmd.3.1.15]

- Navabinejad S. Interdisciplinary perspectives on well-being and intervention strategies across life stages. KMAN Counseling & Psychology Nexus. 2024; 2(1):1-3. [DOI:10.61838/kman.psychnexus.2.1.1]

- Qiu H, Piskorz-Ryń O. Understanding patient adherence to hypertension management guidelines. KMAN Counseling & Psychology Nexus. 2024; 2(1):70-6. [DOI:10.61838/kman.psychnexus.2.1.11]

- Shahraki-Mohammadi A, Panahi S, Ashouri A, Sayarifard A. Important systemic factors for improving adolescent mental health literacy. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2023; 18(1):45-54. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v18i1.11412] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Darbani S, Mirzaei A. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: A review study. Journal of Assessment and Research in Applied Counseling. 2022; 4(1):48-63. [DOI:10.52547/jarac.4.2.48]

- Erlich J, Zhu W, Raj S. The perception of justice among wrongfully convicted individuals: Life after exoneration. Interdisciplinary Studies in Society, Law, and Politics. 2023; 2(2):11-8. [DOI:10.61838/kman.isslp.2.2.3]

- Roach A, Thomas SP, Abdoli S, Wright M, Yates AL. Kids helping kids: The lived experience of adolescents who support friends with mental health needs. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2021; 34(1):32-40. [DOI:10.1111/jcap.12299] [PMID]

- Navabinejad S. Chief-editor’s note: The role of the family in child education. Applied Family Therapy Journal. 2023; 4(3):1-2. [DOI:10.61838/kman.aftj.4.3.1]

- Recto P, Champion JD. Psychological distress and associated factors among Mexican American adolescent females. Hispanic Health Care International. 2016; 14(4):170-6. [DOI:10.1177/1540415316676224] [PMID]

- Kaligis F, Ismail RI, Wiguna T, Prasetyo S, Indriatmi W, Gunardi H, et al. Translation, validity, and reliability of mental health literacy and help-seeking behavior questionnaires in Indonesia. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 12:764666. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.764666] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Boltivets S. Cultural beliefs and mental health. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2023; 1(4):1-3. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.1.4.1]

- Jafari Z, Jafari M. Understanding family functioning: The influence of cultural marginalization and social competence. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2023; 1(4):4-10. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.1.4.2]

- Rostami M, Navabinejad S. Cultural sensitivity in family research: bridging gaps. Journal of Psychosociological Research in Family and Culture. 2023; 1(2):1-4. [DOI:10.61838/kman.jprfc.1.2.1]

- Çevik M, Toker H. Social determinants of health: Legal frameworks for addressing inequities. Interdisciplinary Studies in Society, Law, and Politics. 2022; 1(1):14-22. [DOI:10.61838/kman.isslp.1.1.3]

- Kotwal S. Addressing the gap: The importance of mental health legislation and policy. Interdisciplinary Studies in Society, Law, and Politics. 2022; 1(2):1-3. [DOI:10.61838/kman.isslp.1.2.1]

- Adu Bakare S, Nouhi N. Employee experiences with workplace discrimination law. Interdisciplinary Studies in Society, Law, and Politics. 2024; 3(1):24-30. [DOI:10.61838/kman.isslp.3.1.5]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Health Systems

Received: 2024/05/19 | Accepted: 2024/06/19 | Published: 2025/01/1

Received: 2024/05/19 | Accepted: 2024/06/19 | Published: 2025/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |