Volume 15, Issue 2 (March & April 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(2): 207-216 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zareipour M, Hosseinzadeh F, Soheili A, Mokhtari L. The Viewpoints of Iranian Couples About Childbearing: An Exploratory Qualitative Study. J Research Health 2025; 15 (2) :207-216

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2563-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2563-en.html

1- Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health, Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran.

2- Department of Operating Room, Faculty of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical sciences, Khoy, Iran.

3- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran.

4- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran. ,l.mokhtary@gmail.com

2- Department of Operating Room, Faculty of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical sciences, Khoy, Iran.

3- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran.

4- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 684 kb]

(1028 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3378 Views)

Full-Text: (1020 Views)

Introduction

Deciding on fertility is among the major events of a couple’s life, which in turn affects different aspects of life, such as health, economic status and household welfare [1]. Fertility, as one of the main components of development, has attracted the attention of many social science researchers [2]. Fertility and, consequently, childbearing are among the most emotional experiences of human beings following their desire for continuity of generation and survival. Children could increase love, vitality and mental health and develop the excellence of their parents’ personality [3].

The declining tendency to have children is one of the social problems that Iranian society is facing [4] and significant demographic changes have occurred in fertility, indicating shifts in the population structure [5]. Currently, Iran’s population is in the second stage of transition, some manifestations of which include a noticeable decline in crude birth and death rates and a decreased total fertility rate [6]. In Iran, the general fertility rate decreased to less than one in some areas, and it was 0.6 in some other areas in 2021. Iran will become a country with an aging population if the current situation continues, and, as a result, its active population will decrease [7].

Childbearing is influenced by socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors and is deeply associated with men’s and women’s attitudes and awareness [8]. Various studies have been conducted on factors affecting childbearing. Health concerns can seriously affect the second child’s intentions among couples [2]. In other research, parents’ social status, economic prerequisites, individual readiness, physical health [2], husband’s role and support, and quality of life were reported as effective factors [9].

In the national study by Tavousi et al., concern about ensuring the future of newborns, concern about increasing economic problems by having another child, and considering the current child to be enough, were reported as the most common reasons for being reluctant to have children [10]. According to some studies, increasing access to support resources, especially in child care, and the presence of social networks of family or friends have encouraged couples to have more motivation and intention for childbearing [11]. These developments have changed Iran’s population age structure as well. Iran’s population age pyramid, which has always had a young age structure, has shifted to a middle-aged and elderly structure [12] and is expected to further develop into an elderly structure in the future [7]. The decreased general fertility rate is not specific to Iran; it has occurred in many parts of the world [13]. Identifying the factors forming the basis of fertility behaviors has become one of the most important questions in demography [14].

During the last decade, the general fertility rate in Iran has reached below the replacement level, which is the most significant and fastest fall in fertility ever recorded [15, 16]. Since the preferences and desires of couples are considered the most important determinants of childbearing behavior, and because childbearing is viewed as a priority in Iran—with considerable emphasis on the youth of the population—little attention has been paid to individuals’ experiences in most studies. Furthermore, no research has been conducted in this field at Khoy University of Medical Sciences. Therefore, the present study was carried out to explain the facilitators and barriers to childbearing in Iranian couples in Khoy City. The results could be used to perform the required interventions for childbearing. Most of the research conducted in this field has studied women; one of the innovations of the present study was to conduct interviews with both partners present, allowing for an exploration of the experiences of both women and men regarding the factors affecting childbearing. The findings should be utilized to carry out necessary interventions to encourage childbearing and to support Hadid’s population policy aimed at increasing the population.

Methods

In this exploratory qualitative study, the conventional content analysis method was used to identify the factors affecting childbearing among couples in Khoy City. Conventional content analysis is typically employed in the design of studies aiming to describe a phenomenon [17].

Setting

This study was conducted in three health centers affiliated with Khoy University of Medical Science. Khoy City is the second most populous city in West Azerbaijan Province according to the census of 2015, its population is 348,664 people. There are more than 120,000 people of reproductive age in Khoy City and 80% of the city’s women can become pregnant. The fertility rate and population growth, according to birth statistics from 2021, are 2.13%, compared to 2.10% in the previous year, indicating a decrease in births during these years.

Sampling

The participants were selected using the purposive sampling method. In purposive sampling, researchers choose participants who have experiences with the main phenomenon or basic concepts under investigation [18]. Khoy City was first divided into three regions by classifying health centers based on the economic and social status of the residents in each area. The researcher then selected participants from each of these centers. Subsequently, the researcher took a purposive sample from each region to ensure maximum diversity in participant selection.

Sample size

In qualitative studies, the sample size could not be predetermined. Therefore, the sampling process continued until data saturation. Saturation refers to the point in data collection where newly collected data replicate the previous data and no further new information is obtained [19].

Participants

In this study, 23 couples were interviewed. The inclusion criteria were willingness to be interviewed and share experiences, completing the written informed consent form, and being married for at least one year. The exclusion criterion was the infertility problems of one of the couples. The language used in the study was Azari.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted in the presence of both couples. Each interview session lasted 30-45 minutes. After obtaining demographic information, the interviews began with questions, such as “what factors could increase or decrease your desire to have children in your personal life?” and “in your opinion, what other factors (e.g. friends, relatives, etc.) could contribute to your childbearing?” Probing questions, such as “explain more about this matter” or “could you clarify this matter?” were used. At the end of each interview, participants were asked, ”Is there anything important that you have not mentioned that you would like to share? After conducting 20 interviews, all extracted codes were repeated; however, three additional interviews were conducted to ensure data saturation. All the interviews were transcribed and frequently reviewed to gain a deeper understanding of the content. The interviews were transcribed verbatim, with participants’ emotions noted.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using MAXQDA software, version 12 and the method recommended by Graneheim and Lundman [18, 20, 21]. All the interviews were transcribed and the codes were extracted from the latent and manifest content. It should be noted that the text related to the content aspects describing the obvious and concrete components was considered as the manifest content, while the part dealing with the communication aspect and interpreting the text’s basic concepts was considered latent content [22]. Lindgren’s et al approach emphasizes interpretation and abstraction during the analytic process in order to strengthen the trustworthiness of qualitative content analysis. Qualitative content analysis could be both descriptive and interpretive. Analyzing data based on manifest and descriptive content leads to categories while analyzing data based on latent and interpretive content leads to themes [18]. In this study, the extracted codes were classified into subcategories based on similarities and differences, and the extracted subcategories were re-compared and merged to form categories. Finally, the data concepts and latent content were extracted as the main themes.

Rigor

To ensure data trustworthiness, four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba (1986), including credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, were used [23]. In the present study, prolonged engagement with data, peer review, member checks and selecting participants with different experiences were used to provide credibility. Describing components, recording participants’ characteristics and describing the study design and procedure steps were used to ensure transferability. All research steps, from beginning to end, were explained in detail to ensure dependability, allowing the external audit to conduct the review based on these documents. Continuous monitoring was carried out throughout the research to ensure confirmability.

Results

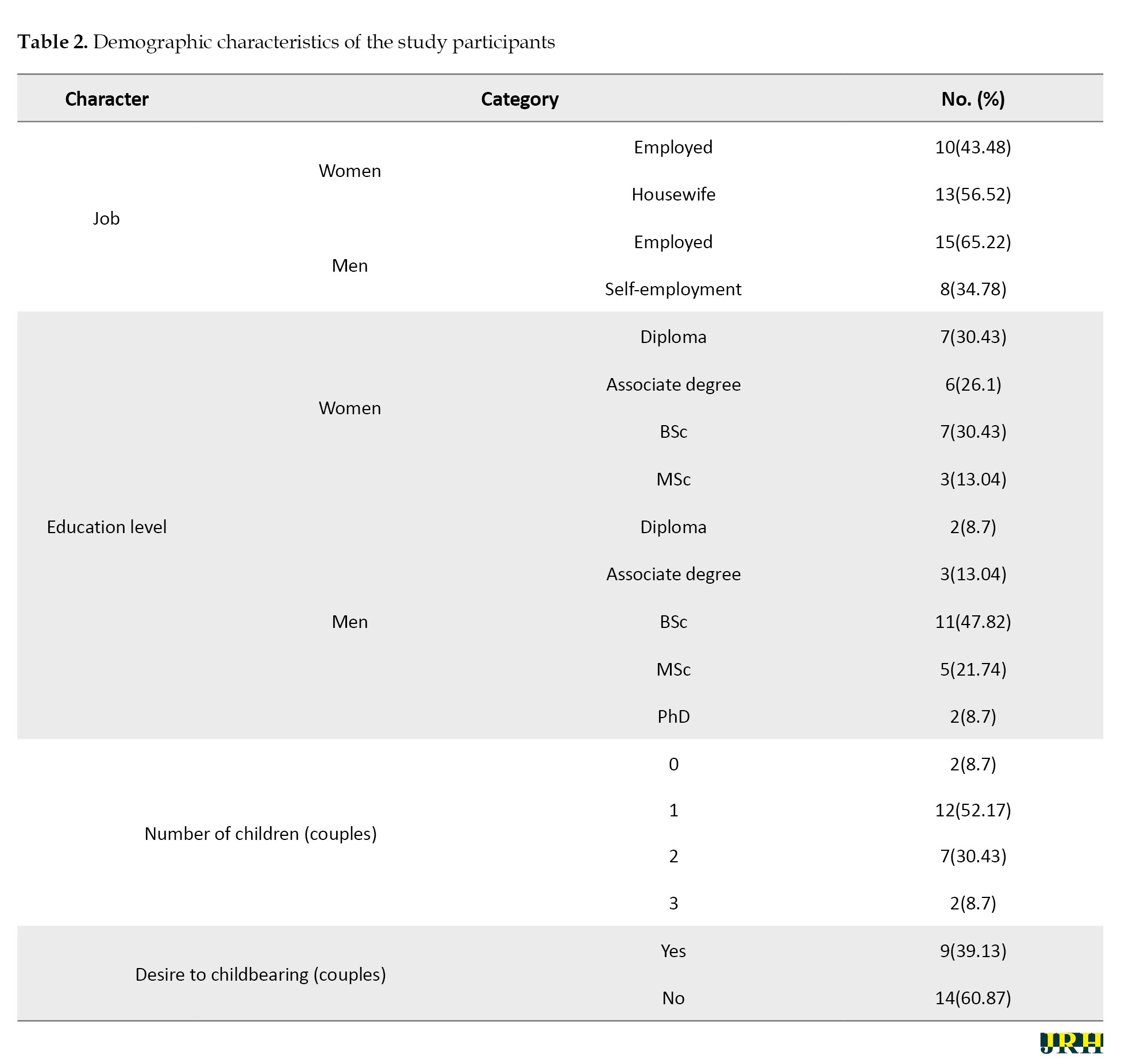

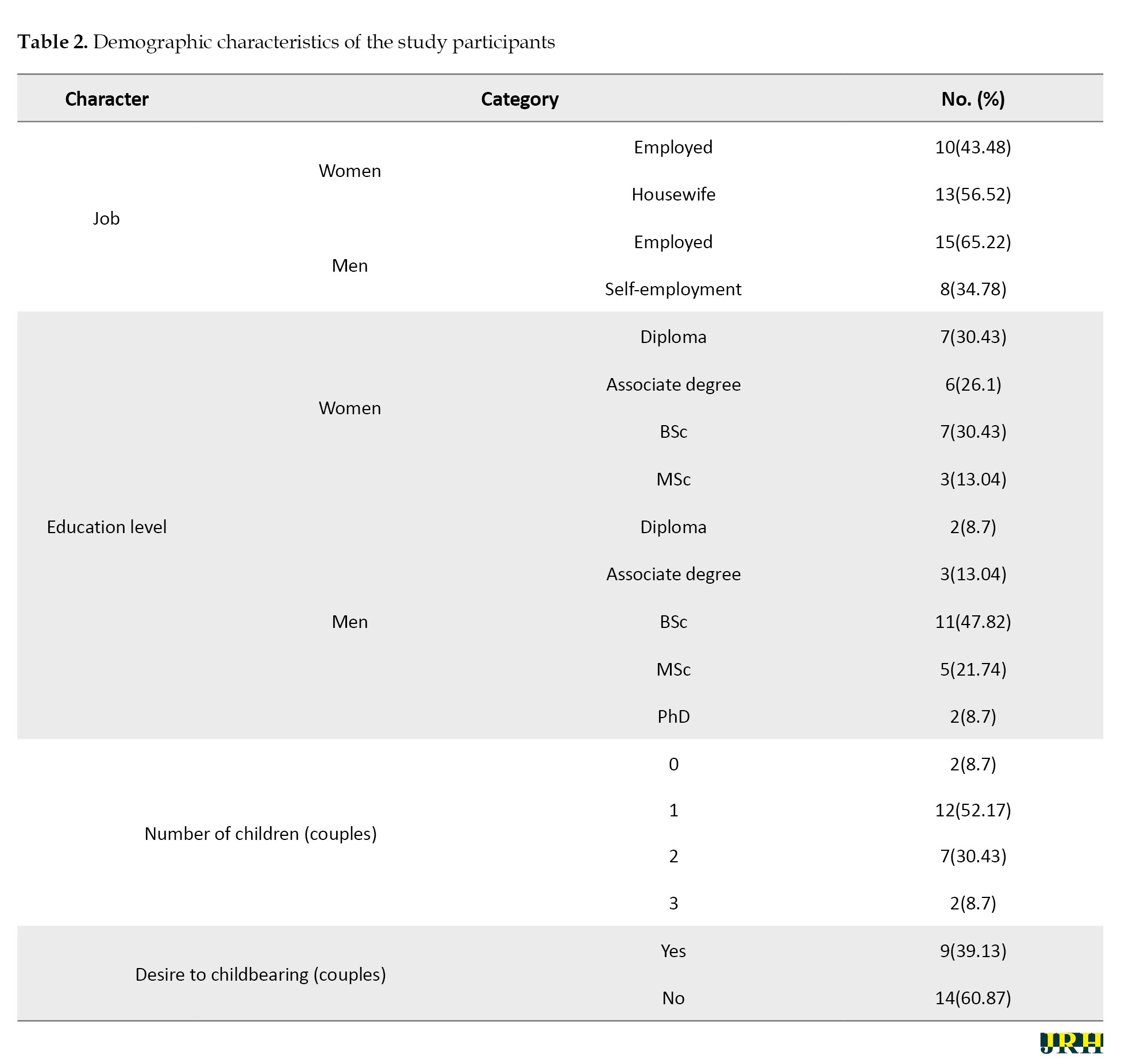

Of the 23 couples participating in the study, 14 couples (60.87%) responded negatively to the initial question of the study regarding childbearing desire. The mean age of men and women was 41.32±2.16 and 36.84±5.37 years, respectively. Table 1 presents other demographic characteristics of the participants.

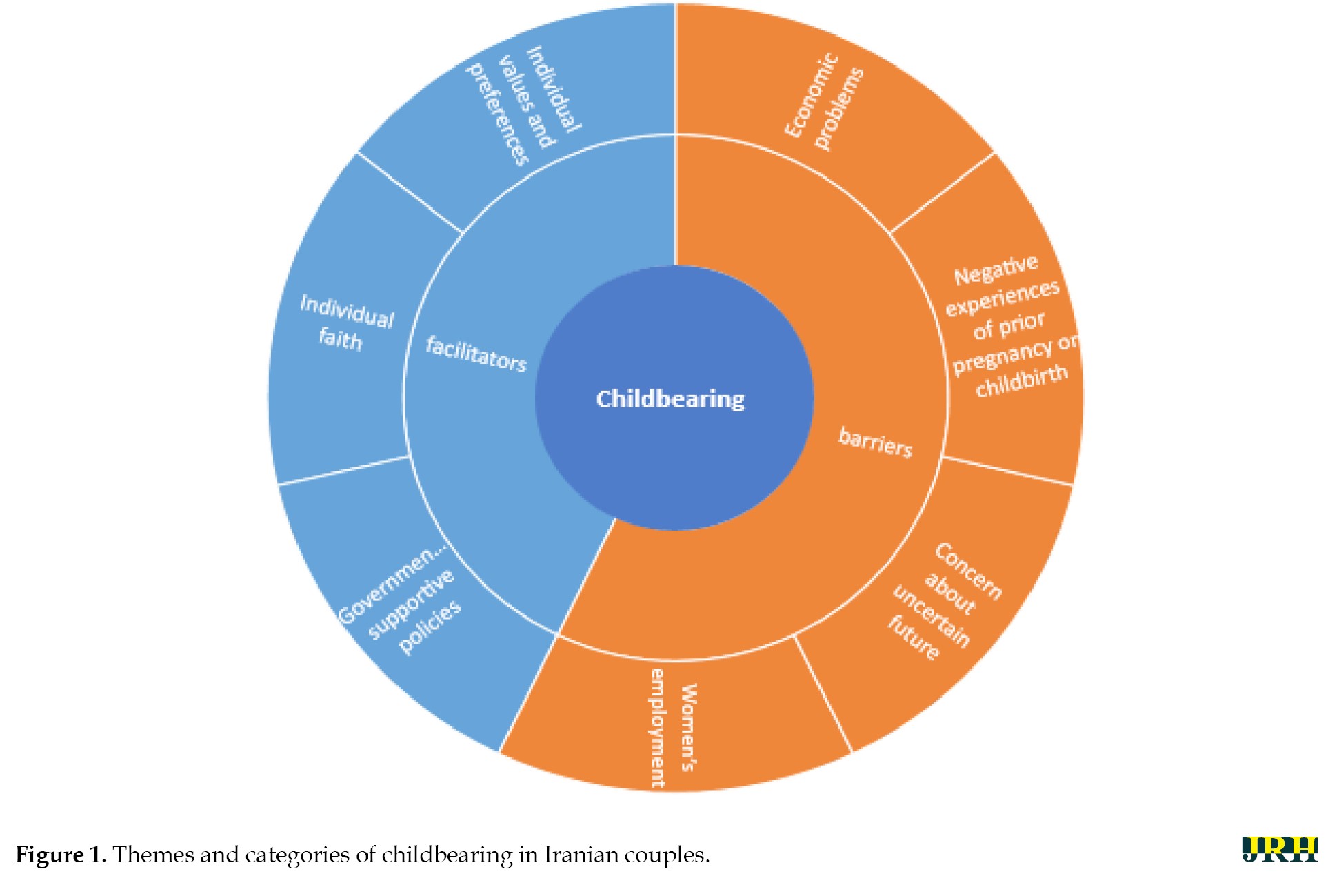

In data analysis, 844 initial codes were identified, which was finally reduced to 88 after merging similar codes. After completing the analysis process, nine categories and two main themes, i.e. childbearing facilitators and childbearing barriers, were extracted from the interviews (Figure 1).

Barriers

The four categories of childbearing barriers included economic problems, concern about an uncertain future, women’s employment challenges and negative experiences of prior pregnancy/childbirth.

Economic problems

All the participants who were reluctant to have children mentioned economic problems as the main reason. Also, they reported problems, such as exorbitant costs of child care, considering having children as being cruel, wide variety of stationery and clothing, competing among children to have diversity in life’s necessities, raising children’s expectations, high cost of enrolling in different classes, and a lack of a suitable job and sufficient income. Couple No. 6, who had a 1.5-year-old daughter, said:

“Having a child in the current bad economic situation is both cruel to ourselves and the child. We paid 15,000,000 Rials for our child’s clothes in the last week!”

Couple No. 18, who had a 14-year-old child, mentioned the reasons for their reluctance to have children:

“It takes a lot of money to raise a child. There is a variety of stationery, clothes, bags, shoes, classes, etc. Children want to have everything that their friends own. When our parents bought a pencil case for us, we tried to keep it for 2-3 years, but now it’s not like this! We enroll our child in different classes every year, even in summer”.

Concern about uncertain future

In the category of concern about an uncertain future, the participants reported several reasons, including insecurity regarding stable employment and the future of their child, numerous life customs, marital conflict, the rise of one-and-done parenting, the perception of having many children as socially undesirable, social role modeling, the serious responsibility of raising children properly and the existence of social paradoxes. Couple No. 15, who had a 16-year-old child and were both working, said:

“Now we are worried about the future of our only child. We pay a lot of money for our child’s entrance exam preparation classes. He is attempting hard, but we don’t know what the future will hold! As you can see, the university entrance exam gets worse every year. Also, violation in the entrance exam has increased”.

Couple No. 9, who had two children, stated:

“Earlier, it was said that having fewer children leads to a better life, but now it is said that having more children leads to a happier life. We don’t know what happened when the slogan changed. Who can give birth to a child in the current situation? Nothing is certain. There is no good future for children. We are all worried about the future of these two children”.

Women’s employment challenges

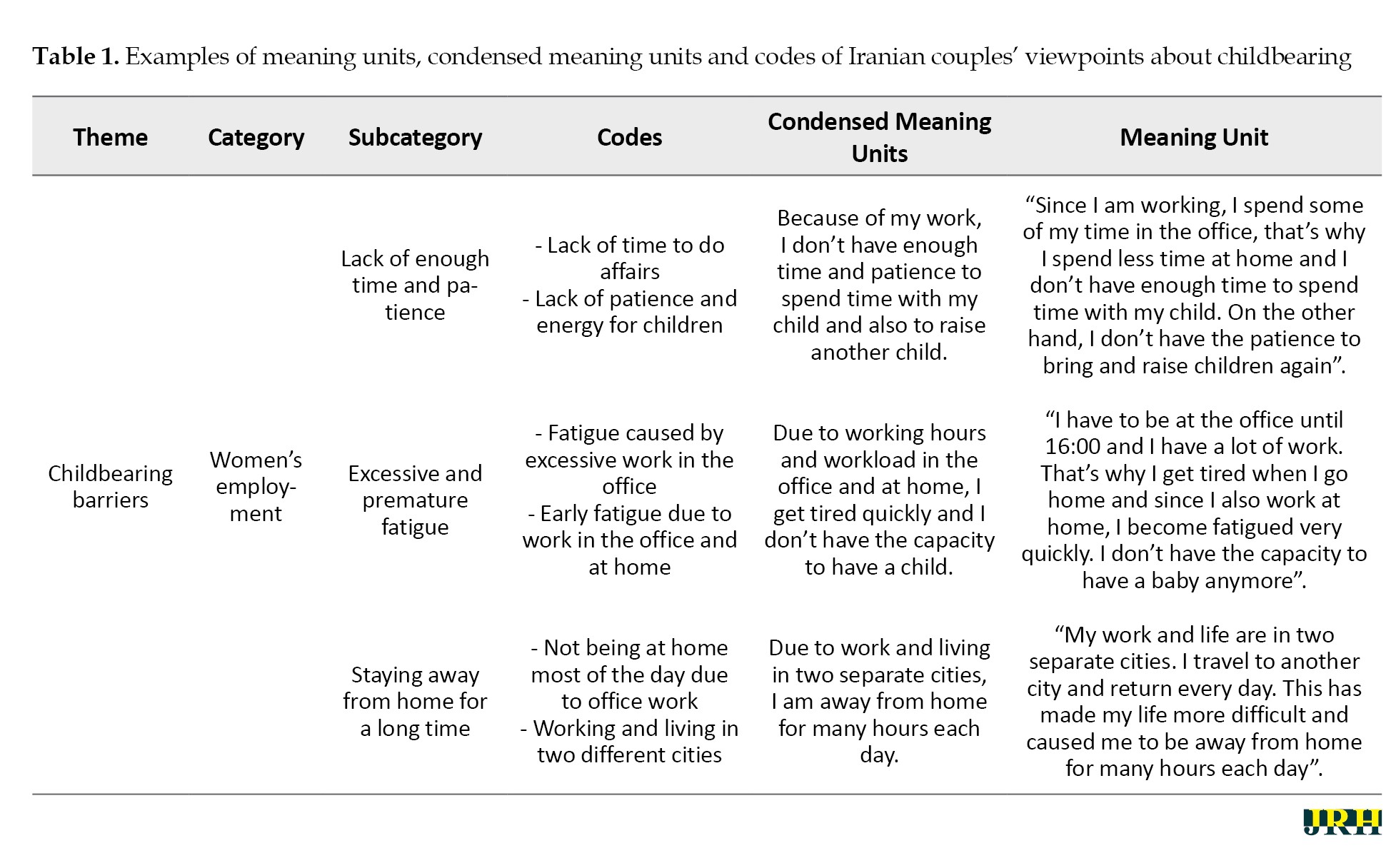

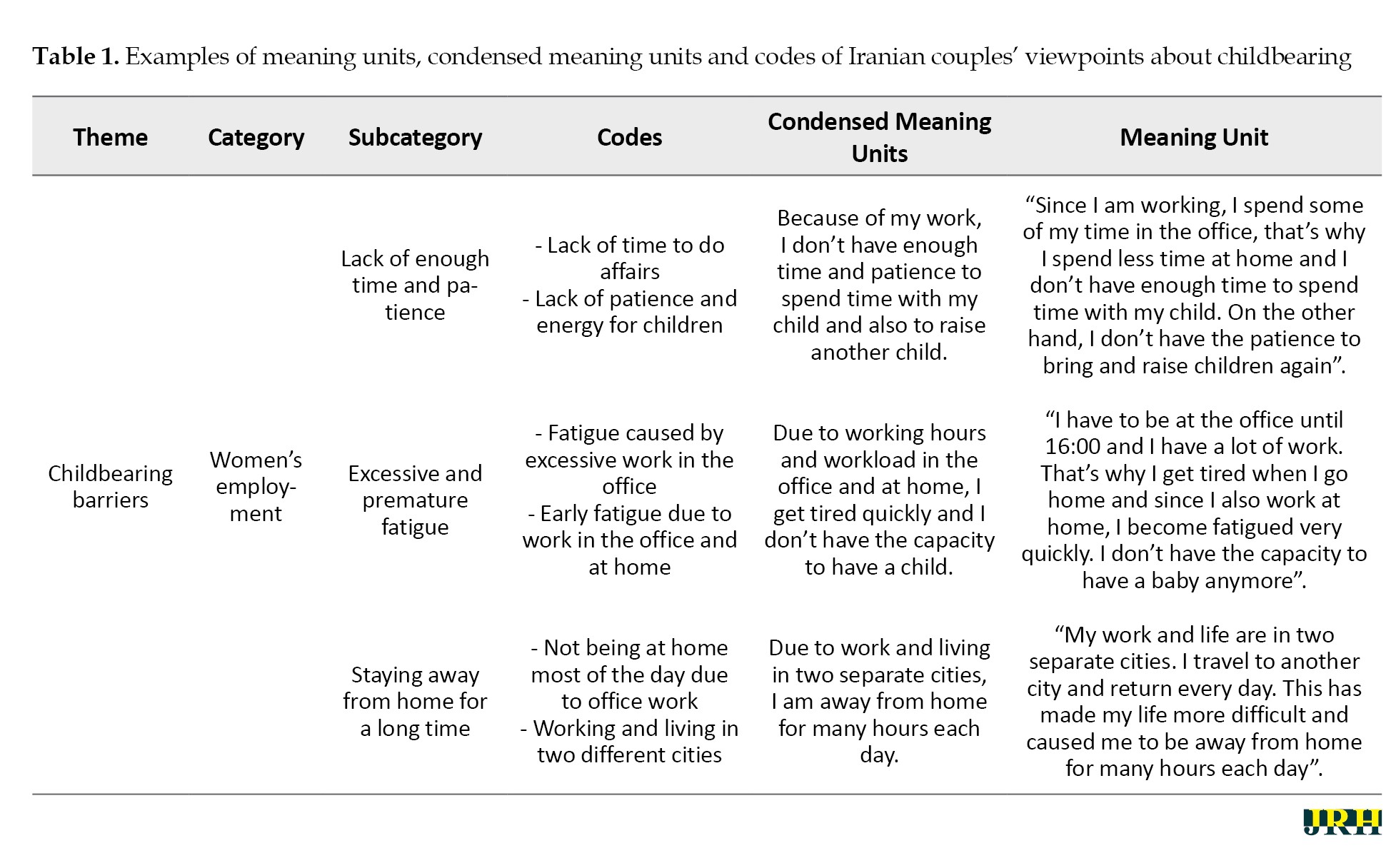

In the category of women’s employment challenges, women mentioned issues, such as working and living in two different cities, a lack of sufficient time and patience, having children, which prevents women from devoting time to their individual preferences, excessive and premature fatigue, problems related to continuing education, an inability to tolerate lack of sleep, difficulties in keeping children in kindergarten, the imposition of all responsibilities on mothers, and being away from home for extended periods (Table 2).

A 42-year-old employed woman with a 12-year-old son said:

“I’m solely responsible for raising and educating my son. My husband does not cooperate. When I go back home from work, I have to cook, help my son with homework, and do housework. My husband does not consider that I am tired and I just came back from work! I can’t even think about having a second child under these conditions”.

A 38-year-old employed woman with one child stated:

“My son has been sick since childhood. I had to put him in kindergarten despite my desire due to my work. I had no one to take care of him every day! I don’t want to experience the same days all over again. On the other hand, I don’t feel like raising the second child anymore. I get tired quickly”.

A 31-year-old working woman who did not have children expressed her experience as follows:

“I am employed and at the same time a graduate student. Although we want to have children, after 3 years of living together, we still have not made a serious decision in this regard. We didn’t take it because my wife and I believe that we should spend time to raise the child.”

Negative experiences of prior pregnancy/childbirth

Finally, in the category of negative experiences related to prior pregnancy or childbirth, mothers who had undesirable experiences discussed pregnancy complications, inappropriate behavior of the delivery room staff, post-delivery physical problems, having restless children, and how getting married at an older age hinders childbearing. A 32-year-old housewife said:

“I got hypertension and diabetes during my pregnancy and was hospitalized at the end of my pregnancy. Doctors said it was highly probable that my baby and I would be harmed (feeling deeply sad). I was much stressed and wished for my child to be born healthy. It is even painful for me to think of getting pregnant for the second time”.

Facilitators

In the theme of childbearing facilitators, three categories were identified: Individual or family values and preferences, individual faith, and the government’s supportive policies.

Individual or family values and preferences

In the category of individual/family values and preferences, the participants who agreed with childbearing discussed beliefs and experiences such as children strengthening family foundations, children being supporters of their parents, the fear of losing an only child, children being companions who can play together, learning to interact with other children, children being the essence and reason for life, a preference for the male gender, only children becoming spoiled, and children resuming friendships and eliminating resentment. The employed 40-year-old man (couple No. 17), who had a 12-year-old daughter, expressed his experience as follows:

“Only children become spoiled and receive all their parents’ attention. They expect that all members of society will meet their needs in the future. Who should the child play with when they are alone? Children play together, fight, and learn to communicate with one another”.

Couple No. 1, who had two children and were both working said:

“We are so dependent on children that we can’t imagine life without them at all! Children make our lives more beautiful with their funny activities”.

Individual faith

In the category of individual faith, Islam’s recommendation to have children, the belief against abortion in cases of unwanted pregnancy, the provision of children’s sustenance by God, religious and ethnic beliefs, viewing the child as a blessing, and adherence to traditional values were mentioned as childbearing facilitators. Couple No. 3, who had three children and whose wife was a housewife and pregnant, said:

“We, as Kurdish people, like kids so much, and most families have many children, and usually women do not have abortions”

A 42-year-old housewife (couple No. 12), who had two children, described her experience as follows:

“God will deliver the child’s sustenance before they are born. I remember that God helped us a lot before the birth of my second child. My husband found a suitable job, and our family’s financial situation changed a lot”.

Government’s supportive policies

In the category of government’s supportive policies, the participants’ experiences included government support for employed mothers, government advertisements for childbearing, government facilities for families with more children, establishing kindergartens at women’s workplaces, providing more services for couples, and enjoying job stability. Couple No. 21, both of whom were working and had two children, said:

“The government has approved that employed women with children under 6 years of age could go to work an hour later. Some offices have kindergartens where mothers could safely leave their children”.

Discussion

In this qualitative study conducted to explain Iranian couples’ viewpoints of childbearing, two themes of childbearing facilitators and barriers were extracted. Most of the participants were reluctant to have children, mainly due to economic problems. In Boivin et al.’s study, economic problems and costs of having children were among the important factors affecting people’s decisions to have children [2]. In Bagi et al.’s study, working conditions and economic costs were among the major reasons for people’s reluctance to have children. In this study, 59.7% of the participants stated that they could not afford the children’s costs [24]. Also, lack of economic security and income level were among the reasons for American couples [25]. The results of these studies are in line with our findings.

Concern about an uncertain future was another reason for the participants’ reluctance to have children. They cited issues such as insecurity regarding proper jobs and the future of their child, marital conflict, the trend of one-and-done parenting, social role modeling, the significant responsibility of raising children properly and the high rate of divorce in society. In Behmanesh et al.’s study, the women participating explained their reasons for having only one child as self-priority, an uncertain future, and living a forced and loveless life due to the fear of divorce. They considered childbearing as a barrier to their well-being and comfort and a limitation in life [13]. These concerns were also expressed by the women participating in our study. In other studies, issues, such as marital conflict [26, 27], concerns about children’s livelihood and education, and an uncertain future for them [13], as well as taking role models from people and media, changes in children’s expectations of their parents, and shifts in couples’ attitudes toward childbearing, were identified as reasons for the low probability of childbearing.

Women’s employment was another barrier to childbearing. Full-time work was a key factor in the decision not to have children among both men and women. Job insecurity. Job insecurity [28, 29], prioritizing oneself, being employed and a lack of sufficient time to raise children [13] could negatively affect childbearing intention, which is in line with our findings. Having children interferes with the working conditions of women or their spouses, and a lack of sufficient time for childbearing was among the reasons for reluctance to have another child [24].

Regarding negative experiences from prior pregnancies or childbirth, teenage mothers faced complications during pregnancy or post-delivery issues. Some did not want to experience these conditions again, especially if they had restless children. In Ghaffari et al.’s study, fear of childbirth was identified as one of the main themes. Women described the pain of childbirth as the most severe pain, which could negatively impact the mother’s mental health and her relationship with the child [4]. In the study by Pirdadeh Beiranvand et al. 80.8% of the women participating in the study were afraid of childbirth [30].

The couples who favored childbearing mentioned individual or family values and preferences as reasons for their agreement. Women chose to have children to meet needs, such as individual needs, satisfying the maternal instinct, love for the child, strengthening the family, providing a sibling for their first child and balancing the family’s gender composition [31]. Also, gender preference [8, 25, 32], a constant fear of losing the only child, child loneliness, and the lack of a supporter in the future [13], as well as resolving marital conflicts after childbearing [4], were concerns raised by the couples participating in the present study.

Individual faith and religious beliefs were other reasons for couples agreeing to have children. Factors, such as religious beliefs and belief in God [33] and the belief that God provides for children’s sustenance [4] led to increased childbearing. Other studies have investigated the role of religion as one of the determinants of fertility tendency and found that Sunni followers are more willing to have children than Shiites [10, 24, 31], which is in line with our findings.

Finally, “government’s supportive policies” were another reason for those who agreed with childbearing. Implementing government incentive policies and political measures, such as granting post-natal leave to fathers, increasing maternity leave from six months to nine months, and limiting the provision of family planning methods to women covered by health centers, were effective in increasing childbearing [4]. In developed countries, governments attempt to reduce the economic costs of raising children by implementing policies such as child allowances, financial incentives, and tax exemptions [34].

Conclusion

Given that most of the participants were reluctant to have children, this indicates that couples’ attitudes toward having children have changed under the influence of various economic, cultural, and religious factors. The couples argued that raising children in this era is completely different from previous decades; for example, children’s expectations of their parents have increased, and the costs of education and raising children have risen alongside changing lifestyles. Employed women preferred to have only one child due to being busy with work, lack of patience, insufficient time, and having uncooperative husbands. The social-biological experiences in Iran demonstrate that people’s behaviors are partially influenced by political and cultural propaganda. Therefore, the government and policymakers should act based on realistic programs and public needs. Also, it is recommended to examine the underlying reasons for the reluctance to have children before persuading couples to do so.

Study limitations and recommendations

Considering that the non-generalizability of the results is one of the characteristics of qualitative research, the obtained results should be generalized with caution, as the participants were selected from only one geographical area. However, appropriate sampling strategies, which included temporal and spatial variation in the selection of participants and data collection, were employed to address this limitation. The inclusion of couples with a mean age above 35 was another limitation of this study. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies include couples with a lower mean age and implement educational interventions to increase couples’ willingness to have children, with the results reported for future planning.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethic Commitment of Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran (Code: IR.KHOY.REC.1402.019). The written informed consent form was completed by all participants.

Funding

This research is extracted from the research project (No. 401000016), approved by the Department of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical Sciences and was supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research at Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Leila Mokhtari and Moradali Zareipour; Data collection: All authors; Data analysis: Leila Mokhtari and Moradali Zareipour; Manuscript preparation and editing: Leila Mokhtari; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Research Deputy of Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran and all the participants in the study.

References

Deciding on fertility is among the major events of a couple’s life, which in turn affects different aspects of life, such as health, economic status and household welfare [1]. Fertility, as one of the main components of development, has attracted the attention of many social science researchers [2]. Fertility and, consequently, childbearing are among the most emotional experiences of human beings following their desire for continuity of generation and survival. Children could increase love, vitality and mental health and develop the excellence of their parents’ personality [3].

The declining tendency to have children is one of the social problems that Iranian society is facing [4] and significant demographic changes have occurred in fertility, indicating shifts in the population structure [5]. Currently, Iran’s population is in the second stage of transition, some manifestations of which include a noticeable decline in crude birth and death rates and a decreased total fertility rate [6]. In Iran, the general fertility rate decreased to less than one in some areas, and it was 0.6 in some other areas in 2021. Iran will become a country with an aging population if the current situation continues, and, as a result, its active population will decrease [7].

Childbearing is influenced by socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors and is deeply associated with men’s and women’s attitudes and awareness [8]. Various studies have been conducted on factors affecting childbearing. Health concerns can seriously affect the second child’s intentions among couples [2]. In other research, parents’ social status, economic prerequisites, individual readiness, physical health [2], husband’s role and support, and quality of life were reported as effective factors [9].

In the national study by Tavousi et al., concern about ensuring the future of newborns, concern about increasing economic problems by having another child, and considering the current child to be enough, were reported as the most common reasons for being reluctant to have children [10]. According to some studies, increasing access to support resources, especially in child care, and the presence of social networks of family or friends have encouraged couples to have more motivation and intention for childbearing [11]. These developments have changed Iran’s population age structure as well. Iran’s population age pyramid, which has always had a young age structure, has shifted to a middle-aged and elderly structure [12] and is expected to further develop into an elderly structure in the future [7]. The decreased general fertility rate is not specific to Iran; it has occurred in many parts of the world [13]. Identifying the factors forming the basis of fertility behaviors has become one of the most important questions in demography [14].

During the last decade, the general fertility rate in Iran has reached below the replacement level, which is the most significant and fastest fall in fertility ever recorded [15, 16]. Since the preferences and desires of couples are considered the most important determinants of childbearing behavior, and because childbearing is viewed as a priority in Iran—with considerable emphasis on the youth of the population—little attention has been paid to individuals’ experiences in most studies. Furthermore, no research has been conducted in this field at Khoy University of Medical Sciences. Therefore, the present study was carried out to explain the facilitators and barriers to childbearing in Iranian couples in Khoy City. The results could be used to perform the required interventions for childbearing. Most of the research conducted in this field has studied women; one of the innovations of the present study was to conduct interviews with both partners present, allowing for an exploration of the experiences of both women and men regarding the factors affecting childbearing. The findings should be utilized to carry out necessary interventions to encourage childbearing and to support Hadid’s population policy aimed at increasing the population.

Methods

In this exploratory qualitative study, the conventional content analysis method was used to identify the factors affecting childbearing among couples in Khoy City. Conventional content analysis is typically employed in the design of studies aiming to describe a phenomenon [17].

Setting

This study was conducted in three health centers affiliated with Khoy University of Medical Science. Khoy City is the second most populous city in West Azerbaijan Province according to the census of 2015, its population is 348,664 people. There are more than 120,000 people of reproductive age in Khoy City and 80% of the city’s women can become pregnant. The fertility rate and population growth, according to birth statistics from 2021, are 2.13%, compared to 2.10% in the previous year, indicating a decrease in births during these years.

Sampling

The participants were selected using the purposive sampling method. In purposive sampling, researchers choose participants who have experiences with the main phenomenon or basic concepts under investigation [18]. Khoy City was first divided into three regions by classifying health centers based on the economic and social status of the residents in each area. The researcher then selected participants from each of these centers. Subsequently, the researcher took a purposive sample from each region to ensure maximum diversity in participant selection.

Sample size

In qualitative studies, the sample size could not be predetermined. Therefore, the sampling process continued until data saturation. Saturation refers to the point in data collection where newly collected data replicate the previous data and no further new information is obtained [19].

Participants

In this study, 23 couples were interviewed. The inclusion criteria were willingness to be interviewed and share experiences, completing the written informed consent form, and being married for at least one year. The exclusion criterion was the infertility problems of one of the couples. The language used in the study was Azari.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted in the presence of both couples. Each interview session lasted 30-45 minutes. After obtaining demographic information, the interviews began with questions, such as “what factors could increase or decrease your desire to have children in your personal life?” and “in your opinion, what other factors (e.g. friends, relatives, etc.) could contribute to your childbearing?” Probing questions, such as “explain more about this matter” or “could you clarify this matter?” were used. At the end of each interview, participants were asked, ”Is there anything important that you have not mentioned that you would like to share? After conducting 20 interviews, all extracted codes were repeated; however, three additional interviews were conducted to ensure data saturation. All the interviews were transcribed and frequently reviewed to gain a deeper understanding of the content. The interviews were transcribed verbatim, with participants’ emotions noted.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using MAXQDA software, version 12 and the method recommended by Graneheim and Lundman [18, 20, 21]. All the interviews were transcribed and the codes were extracted from the latent and manifest content. It should be noted that the text related to the content aspects describing the obvious and concrete components was considered as the manifest content, while the part dealing with the communication aspect and interpreting the text’s basic concepts was considered latent content [22]. Lindgren’s et al approach emphasizes interpretation and abstraction during the analytic process in order to strengthen the trustworthiness of qualitative content analysis. Qualitative content analysis could be both descriptive and interpretive. Analyzing data based on manifest and descriptive content leads to categories while analyzing data based on latent and interpretive content leads to themes [18]. In this study, the extracted codes were classified into subcategories based on similarities and differences, and the extracted subcategories were re-compared and merged to form categories. Finally, the data concepts and latent content were extracted as the main themes.

Rigor

To ensure data trustworthiness, four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba (1986), including credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, were used [23]. In the present study, prolonged engagement with data, peer review, member checks and selecting participants with different experiences were used to provide credibility. Describing components, recording participants’ characteristics and describing the study design and procedure steps were used to ensure transferability. All research steps, from beginning to end, were explained in detail to ensure dependability, allowing the external audit to conduct the review based on these documents. Continuous monitoring was carried out throughout the research to ensure confirmability.

Results

Of the 23 couples participating in the study, 14 couples (60.87%) responded negatively to the initial question of the study regarding childbearing desire. The mean age of men and women was 41.32±2.16 and 36.84±5.37 years, respectively. Table 1 presents other demographic characteristics of the participants.

In data analysis, 844 initial codes were identified, which was finally reduced to 88 after merging similar codes. After completing the analysis process, nine categories and two main themes, i.e. childbearing facilitators and childbearing barriers, were extracted from the interviews (Figure 1).

Barriers

The four categories of childbearing barriers included economic problems, concern about an uncertain future, women’s employment challenges and negative experiences of prior pregnancy/childbirth.

Economic problems

All the participants who were reluctant to have children mentioned economic problems as the main reason. Also, they reported problems, such as exorbitant costs of child care, considering having children as being cruel, wide variety of stationery and clothing, competing among children to have diversity in life’s necessities, raising children’s expectations, high cost of enrolling in different classes, and a lack of a suitable job and sufficient income. Couple No. 6, who had a 1.5-year-old daughter, said:

“Having a child in the current bad economic situation is both cruel to ourselves and the child. We paid 15,000,000 Rials for our child’s clothes in the last week!”

Couple No. 18, who had a 14-year-old child, mentioned the reasons for their reluctance to have children:

“It takes a lot of money to raise a child. There is a variety of stationery, clothes, bags, shoes, classes, etc. Children want to have everything that their friends own. When our parents bought a pencil case for us, we tried to keep it for 2-3 years, but now it’s not like this! We enroll our child in different classes every year, even in summer”.

Concern about uncertain future

In the category of concern about an uncertain future, the participants reported several reasons, including insecurity regarding stable employment and the future of their child, numerous life customs, marital conflict, the rise of one-and-done parenting, the perception of having many children as socially undesirable, social role modeling, the serious responsibility of raising children properly and the existence of social paradoxes. Couple No. 15, who had a 16-year-old child and were both working, said:

“Now we are worried about the future of our only child. We pay a lot of money for our child’s entrance exam preparation classes. He is attempting hard, but we don’t know what the future will hold! As you can see, the university entrance exam gets worse every year. Also, violation in the entrance exam has increased”.

Couple No. 9, who had two children, stated:

“Earlier, it was said that having fewer children leads to a better life, but now it is said that having more children leads to a happier life. We don’t know what happened when the slogan changed. Who can give birth to a child in the current situation? Nothing is certain. There is no good future for children. We are all worried about the future of these two children”.

Women’s employment challenges

In the category of women’s employment challenges, women mentioned issues, such as working and living in two different cities, a lack of sufficient time and patience, having children, which prevents women from devoting time to their individual preferences, excessive and premature fatigue, problems related to continuing education, an inability to tolerate lack of sleep, difficulties in keeping children in kindergarten, the imposition of all responsibilities on mothers, and being away from home for extended periods (Table 2).

A 42-year-old employed woman with a 12-year-old son said:

“I’m solely responsible for raising and educating my son. My husband does not cooperate. When I go back home from work, I have to cook, help my son with homework, and do housework. My husband does not consider that I am tired and I just came back from work! I can’t even think about having a second child under these conditions”.

A 38-year-old employed woman with one child stated:

“My son has been sick since childhood. I had to put him in kindergarten despite my desire due to my work. I had no one to take care of him every day! I don’t want to experience the same days all over again. On the other hand, I don’t feel like raising the second child anymore. I get tired quickly”.

A 31-year-old working woman who did not have children expressed her experience as follows:

“I am employed and at the same time a graduate student. Although we want to have children, after 3 years of living together, we still have not made a serious decision in this regard. We didn’t take it because my wife and I believe that we should spend time to raise the child.”

Negative experiences of prior pregnancy/childbirth

Finally, in the category of negative experiences related to prior pregnancy or childbirth, mothers who had undesirable experiences discussed pregnancy complications, inappropriate behavior of the delivery room staff, post-delivery physical problems, having restless children, and how getting married at an older age hinders childbearing. A 32-year-old housewife said:

“I got hypertension and diabetes during my pregnancy and was hospitalized at the end of my pregnancy. Doctors said it was highly probable that my baby and I would be harmed (feeling deeply sad). I was much stressed and wished for my child to be born healthy. It is even painful for me to think of getting pregnant for the second time”.

Facilitators

In the theme of childbearing facilitators, three categories were identified: Individual or family values and preferences, individual faith, and the government’s supportive policies.

Individual or family values and preferences

In the category of individual/family values and preferences, the participants who agreed with childbearing discussed beliefs and experiences such as children strengthening family foundations, children being supporters of their parents, the fear of losing an only child, children being companions who can play together, learning to interact with other children, children being the essence and reason for life, a preference for the male gender, only children becoming spoiled, and children resuming friendships and eliminating resentment. The employed 40-year-old man (couple No. 17), who had a 12-year-old daughter, expressed his experience as follows:

“Only children become spoiled and receive all their parents’ attention. They expect that all members of society will meet their needs in the future. Who should the child play with when they are alone? Children play together, fight, and learn to communicate with one another”.

Couple No. 1, who had two children and were both working said:

“We are so dependent on children that we can’t imagine life without them at all! Children make our lives more beautiful with their funny activities”.

Individual faith

In the category of individual faith, Islam’s recommendation to have children, the belief against abortion in cases of unwanted pregnancy, the provision of children’s sustenance by God, religious and ethnic beliefs, viewing the child as a blessing, and adherence to traditional values were mentioned as childbearing facilitators. Couple No. 3, who had three children and whose wife was a housewife and pregnant, said:

“We, as Kurdish people, like kids so much, and most families have many children, and usually women do not have abortions”

A 42-year-old housewife (couple No. 12), who had two children, described her experience as follows:

“God will deliver the child’s sustenance before they are born. I remember that God helped us a lot before the birth of my second child. My husband found a suitable job, and our family’s financial situation changed a lot”.

Government’s supportive policies

In the category of government’s supportive policies, the participants’ experiences included government support for employed mothers, government advertisements for childbearing, government facilities for families with more children, establishing kindergartens at women’s workplaces, providing more services for couples, and enjoying job stability. Couple No. 21, both of whom were working and had two children, said:

“The government has approved that employed women with children under 6 years of age could go to work an hour later. Some offices have kindergartens where mothers could safely leave their children”.

Discussion

In this qualitative study conducted to explain Iranian couples’ viewpoints of childbearing, two themes of childbearing facilitators and barriers were extracted. Most of the participants were reluctant to have children, mainly due to economic problems. In Boivin et al.’s study, economic problems and costs of having children were among the important factors affecting people’s decisions to have children [2]. In Bagi et al.’s study, working conditions and economic costs were among the major reasons for people’s reluctance to have children. In this study, 59.7% of the participants stated that they could not afford the children’s costs [24]. Also, lack of economic security and income level were among the reasons for American couples [25]. The results of these studies are in line with our findings.

Concern about an uncertain future was another reason for the participants’ reluctance to have children. They cited issues such as insecurity regarding proper jobs and the future of their child, marital conflict, the trend of one-and-done parenting, social role modeling, the significant responsibility of raising children properly and the high rate of divorce in society. In Behmanesh et al.’s study, the women participating explained their reasons for having only one child as self-priority, an uncertain future, and living a forced and loveless life due to the fear of divorce. They considered childbearing as a barrier to their well-being and comfort and a limitation in life [13]. These concerns were also expressed by the women participating in our study. In other studies, issues, such as marital conflict [26, 27], concerns about children’s livelihood and education, and an uncertain future for them [13], as well as taking role models from people and media, changes in children’s expectations of their parents, and shifts in couples’ attitudes toward childbearing, were identified as reasons for the low probability of childbearing.

Women’s employment was another barrier to childbearing. Full-time work was a key factor in the decision not to have children among both men and women. Job insecurity. Job insecurity [28, 29], prioritizing oneself, being employed and a lack of sufficient time to raise children [13] could negatively affect childbearing intention, which is in line with our findings. Having children interferes with the working conditions of women or their spouses, and a lack of sufficient time for childbearing was among the reasons for reluctance to have another child [24].

Regarding negative experiences from prior pregnancies or childbirth, teenage mothers faced complications during pregnancy or post-delivery issues. Some did not want to experience these conditions again, especially if they had restless children. In Ghaffari et al.’s study, fear of childbirth was identified as one of the main themes. Women described the pain of childbirth as the most severe pain, which could negatively impact the mother’s mental health and her relationship with the child [4]. In the study by Pirdadeh Beiranvand et al. 80.8% of the women participating in the study were afraid of childbirth [30].

The couples who favored childbearing mentioned individual or family values and preferences as reasons for their agreement. Women chose to have children to meet needs, such as individual needs, satisfying the maternal instinct, love for the child, strengthening the family, providing a sibling for their first child and balancing the family’s gender composition [31]. Also, gender preference [8, 25, 32], a constant fear of losing the only child, child loneliness, and the lack of a supporter in the future [13], as well as resolving marital conflicts after childbearing [4], were concerns raised by the couples participating in the present study.

Individual faith and religious beliefs were other reasons for couples agreeing to have children. Factors, such as religious beliefs and belief in God [33] and the belief that God provides for children’s sustenance [4] led to increased childbearing. Other studies have investigated the role of religion as one of the determinants of fertility tendency and found that Sunni followers are more willing to have children than Shiites [10, 24, 31], which is in line with our findings.

Finally, “government’s supportive policies” were another reason for those who agreed with childbearing. Implementing government incentive policies and political measures, such as granting post-natal leave to fathers, increasing maternity leave from six months to nine months, and limiting the provision of family planning methods to women covered by health centers, were effective in increasing childbearing [4]. In developed countries, governments attempt to reduce the economic costs of raising children by implementing policies such as child allowances, financial incentives, and tax exemptions [34].

Conclusion

Given that most of the participants were reluctant to have children, this indicates that couples’ attitudes toward having children have changed under the influence of various economic, cultural, and religious factors. The couples argued that raising children in this era is completely different from previous decades; for example, children’s expectations of their parents have increased, and the costs of education and raising children have risen alongside changing lifestyles. Employed women preferred to have only one child due to being busy with work, lack of patience, insufficient time, and having uncooperative husbands. The social-biological experiences in Iran demonstrate that people’s behaviors are partially influenced by political and cultural propaganda. Therefore, the government and policymakers should act based on realistic programs and public needs. Also, it is recommended to examine the underlying reasons for the reluctance to have children before persuading couples to do so.

Study limitations and recommendations

Considering that the non-generalizability of the results is one of the characteristics of qualitative research, the obtained results should be generalized with caution, as the participants were selected from only one geographical area. However, appropriate sampling strategies, which included temporal and spatial variation in the selection of participants and data collection, were employed to address this limitation. The inclusion of couples with a mean age above 35 was another limitation of this study. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies include couples with a lower mean age and implement educational interventions to increase couples’ willingness to have children, with the results reported for future planning.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethic Commitment of Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran (Code: IR.KHOY.REC.1402.019). The written informed consent form was completed by all participants.

Funding

This research is extracted from the research project (No. 401000016), approved by the Department of Nursing, Khoy University of Medical Sciences and was supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research at Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Leila Mokhtari and Moradali Zareipour; Data collection: All authors; Data analysis: Leila Mokhtari and Moradali Zareipour; Manuscript preparation and editing: Leila Mokhtari; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Research Deputy of Khoy University of Medical Sciences, Khoy, Iran and all the participants in the study.

References

- Su-Russell C, Sanner C. Chinese childbearing decision-making in mainland China in the post-one-child-policy era. Family Process. 2023; 62(1):302-18. [DOI:10.1111/famp.12772] [PMID]

- Boivin J, Buntin L, Kalebic N, Harrison C. What makes people ready to conceive? Findings from the international fertility decision-making study. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online. 2018; 6:90-101. [DOI:10.1016/j.rbms.2018.10.012] [PMID]

- Cleland J, Machiyama K, Casterline JB. Fertility preferences and subsequent childbearing in Africa and Asia: A synthesis of evidence from longitudinal studies in 28 populations. Population Studies. 2020; 74(1):1-21 [DOI:10.1080/00324728.2019.1672880] [PMID]

- Ghaffari F, Motaghi Z. [Factors affecting childbearing based on women’s perspectives: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Navid No. 2021; 23(76):33-43. [DOI:10.22038/nnj.2020.52797.1238]

- Torabi F, Sheidani R. A study of effective factors in tendency to fewer childbearing of 15-49 year old women residents of Tehran. Journal of Woman and Family Studies. 2019; 7(2):31-67. [Link]

- Rabiei Z, Shariati M, Mogharabian N, Tahmasebi R, Ghiasi A, Motaghi Z. Exploring the reproductive health needs of men in the preconception period: A qualitative study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2022; 11:208. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_58_22] [PMID]

- Naderi Beni M, Sharifi M, Kordzanganeh J. [Fertility changes in iran based on parity progression ratio, 2006-2016 (Persian)]. Journal of Population Association of Iran. 2021; 16(31):133-57. [DOI:10.22034/jpai.2022.541705.1204]

- Baki-Hashemi S, Kariman N, Ghanbari S, Pourhoseingholi MA, Moradi M. Factors affecting the decline in childbearing in Iran: A systematic review. Advances in Nursing & Midwifery. 2018; 27(4):11-9. [Link]

- Sodik MA, Nzilibili SMM. The role of health promotion and family support with attitude of couples childbearing age in following family planning program in health. Journal of Global Research in Public Health. 2017; 2(2):82-9. [Link]

- Tavousi M, Haerimehrizi A, Sadighi J, Motlagh ME, Eslami M, Naghizadeh F, et al. [Fertility desire among Iranians: A nationwide study (Persian)]. Payesh. 2017; 16(4):401-10. [Link]

- Afarini FS, Akbari N, Montazeri A. [The relationship between social support and the intention of childbearing in women of reproductive age (Persian)]. Payesh. 2018 ; 17(3):315-28. [Link]

- Zanjani HA. [Demographic changes of the household in Iran (Persian)]. Journal of Population Association of Iran. 2016; 1(1):61-80. [Link]

- Behmanesh F, Taghizadeh Z, Vedadhir A, Ebadi A, Pourreza A, Abbasi Shavazi M. [Explaining the causes of single child based on women’s views: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Epidemiology. 2019; 15(3):279-88. [Link]

- Michael RD, Webster CA, Egan CA, Nilges L, Brian A, Johnson R, et al. Facilitators and barriers to movement integration in elementary classrooms: A systematic review. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2019; 90(2):151-62. [DOI:10.1080/02701367.2019.1571675] [PMID]

- Ahmadi SE, Rafiey H, Sajjadi H, Nosratinejad F. [Explanatory model of voluntary childlessness among Iranian couples in Tehran: A grounded theory approachy (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2019; 44(6):449. [DOI:10.30476/ijms.2019.44964]

- Poorolajal J. Resistance economy and new population policy in Iran. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2017; 17(1):367. [PMCID]

- Nieforth LO, Rodriguez KE, O'Haire ME. Expectations versus experiences of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) service dogs: An inductive conventional content analysis. Psychological Trauma. 2022; 14(3):347-56. [DOI:10.1037/tra0001021] [PMID]

- Lindgren BM, Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020; 108:103632. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632] [PMID]

- Guest G, Namey E, Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. Plos One. 2020; 15(5):e0232076. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0232076] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today. 2017; 56:29-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Guerrero-Torrelles M, Monforte-Royo C, Tomás-Sábado J, Marimon F, Porta-Sales J, Balaguer A. Meaning in life as a mediator between physical impairment and the wish to hasten death in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2017; 54(6):826-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.018] [PMID]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation. 1986; 1986(30):73-84. [DOI:10.1002/ev.1427]

- Bagi M, Sadeghi R, Hatami A. [Fertility intentions in Iran: Determinants and limitations (Persian)]. Quarterly of Strategic Studies of Culture. 2022; 1(4):59-79. [DOI:10.22083/scsj.2022.149113]

- Brauner-Otto SR, Geist C. Uncertainty, doubts, and delays: Economic circumstances and childbearing expectations among emerging adults. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2018; 39:88-102. [DOI:10.1007/s10834-017-9548-1]

- Harold GT, Leve LD. Parents as partners: How the parental relationship affects children’s psychological development. In: Balfour A, Morgan M, Vincent C, editors. How couple relationships shape our world. Milton Park: Routledge; 2012. [DOI:10.4324/9780429475597-3]

- Van Winkle ZJ. The complexity of family life courses in 20th century Europe and the United States [Doctoral Thesis]. Berlin: Humboldt University of Berlin; 2018. [Link]

- Hanappi D, Ryser VA, Bernardi L, Le Goff JM. Changes in employment uncertainty and the fertility intention-realization link: An analysis based on the swiss household panel. European Journal of Population. 2017; 33(3):381-407. [DOI:10.1007/s10680-016-9408-y] [PMID]

- Vignoli D, Mencarini L, Alderotti G. Is the effect of job uncertainty on fertility intentions channeled by subjective well-being? Advances in Life Course Research. 2020; 46:100343. [DOI:10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100343] [PMID]

- Pirdadeh Beiranvand S, Moghadam Behboodi Z, Salsali M, Alav iMajd H, Birjandi M, Bostani Khalesi Z. Prevalence of fear of childbirth and its associated factors in primigravid women: A cross-sectional study. Shiraz E-Medical Journal. 2017; 18(11):1-9. [DOI:10.5812/semj.61896]

- Hosseini H, Pakseresht S, Rezaei M, Mehrganfar M. [Qualitative analysis of child-rearing activities of Arab couples in Ahvaz city (Persian)]. Journal of Population Association of Iran. 2015; 9(17):141-69. [Link]

- Hashemzadeh M, Shariati M, Mohammad Nazari A, Keramat A. Childbearing intention and its associated factors: A systematic review. Nursing Open. 2021; 8(5):2354-68. [DOI:10.1002/nop2.849] [PMID]

- Preis H, Tovim S, Mor P, Grisaru-Granovsky S, Samueloff A, Benyamini Y. Fertility intentions and the way they change following birth- A prospective longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):228. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-02922-y] [PMID]

- Mencarini L, Vignoli D, Gottard A. Fertility intentions and outcomes: Implementing the theory of planned behavior with graphical models. Advances in Life Course Research. 2015; 23:14-28. [DOI:10.1016/j.alcr.2014.12.004] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Health Systems

Received: 2024/05/29 | Accepted: 2024/08/10 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2024/05/29 | Accepted: 2024/08/10 | Published: 2025/03/2

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |