Volume 15, Issue 1 (Jan & Feb 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(1): 51-60 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 20/472 08.01.2021

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ustundag A. Effect of a Sexual Abuse Prevention Program on Children’s Knowledge About Abuse. J Research Health 2025; 15 (1) :51-60

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2565-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2565-en.html

Department of Child Development, Gülhane Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Health Sciences, Ankara, Turkey. , alev.ustundag@sbu.edu.tr

Full-Text [PDF 717 kb]

(963 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3261 Views)

Full-Text: (1446 Views)

Introduction

Child sexual abuse (CSA) refers to the involvement of a developmentally unready child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully understand or accept, which violates laws or social taboos. Perpetrators of CSA may be adults with specific authority or responsibility for the victim and other children [1]. In the broadest sense, CSA describes any attempt by an adult to exploit a child for personal satisfaction [1]. The most critical factors in CSA are children’s inability to recognize the sexual abuse behaviors and the lack of decision-making skills [2]. The United Nations convention on the rights of the children defines people under 18 as children [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) [4] reported that there were approximately 2.3 billion children in the world in 2017, and 12% were exposed to sexual abuse in the same year [5]. Therefore, CSA is a global public health problem [6]. CSA is associated with multiple negative outcomes, such as mental health issues (e.g. anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and physical health problems (e.g. infectious diseases, musculoskeletal pain, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic fatigue, headaches, and cardio-respiratory problems) [7, 8]. It is prevalent in all national and ethnic origins [9, 10].

Identifying CSA is challenging because it can persist for several years [11], and it often remains undetected unless children disclose that they have been abused [12]. Besides, CSA includes a wide range of sexual behaviors, from exhibitionism to physical contact, which complicates confirmation of abuse [13]. According to the Human Rights Association (IHD) [14], sexual abuse victims are at different stages of cognitive and language development, which may be one of the reasons behind children’s silence and doubts about disclosing sexual abuse. Therefore, it is essential to distinguish between normal and abnormal sexual behaviors and have accurate information about the physical symptoms of sexual abuse [15, 16]. CSA prevention programs have been implemented for two decades [17].

Families play a significant role in the prevention of CSA, although they often have concerns about delivering such education. CSA is a major public health issue that can have long-lasting psychological, emotional, and physical effects on victims. Understanding how to effectively educate parents about preventing such abuse is crucial. Üstündağ et al. [18] found that sexual abuse education positively enhanced parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Despite the availability of various CSA prevention programs, there is limited research on the direct impact of educating parents on their children’s knowledge about abuse. This study addresses this gap by evaluating whether CSA prevention education for parents increases the knowledge levels of children. Accordingly, the causal hypothesis was established: “Parent program improves children’s awareness and knowledge of sexual abuse”. In line with the purpose of the research, the following questions were posed:

1. Does a CSA prevention program make a significant difference in the pre- and post-test scores of parents’ perceptions of sexual abuse?

2. Is there a significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores regarding sexual abuse knowledge and awareness levels?

3. What is the sexual abuse knowledge level of children?

Methods

Research design

This quantitative quasi-experimental study employed the pre-test and post-test design to establish a cause-and-effect relationship [19].

Participants

The study was carried out in the Bağlıca district of Ankara. Since most schools were closed due to the pandemic, only 3 of 12 preschools in the Bağlıca district participated in the study. A total of 229 parents were randomized across the three preschools, of whom 152 volunteered for the study. However, some parents withdrew from the study because they did not want to continue the program or complete the final test. Similarly, some children left the study as they did not wish to complete the final test. Finally, 108 parents and 109 children were included in the study. There was one parent per family. The ages of the children ranged from five to six. Participation in the study was voluntary and informed consent forms were also obtained from the parents.

The inclusion criteria for parents were having a child between the ages of 3 and 6, attending a preschool in the Bağlıca district, volunteering to participate in the study, and attending the education program regularly. Inappropriate and improperly completed scales were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, parents who did not attend the education program regularly were also excluded from the study.

There were 100 mothers and eight fathers in the sample. The parents’ ages ranged from 28 to 35 years. All the parents had an undergraduate degree and were employed in different professions, such as officer, lawyer, accountant, industrial engineer, pharmacist, doctor, architect, social worker, chemist, nutritionist, writer, police officer, teacher, computer specialist, nurse, and construction engineer. The children were the firstborn in their families, with 46 children aged five and 63 children aged six. Since one parent had twins, the total number of children was 109, comprising 44 boys and 64 girls.

Data collection tools

Data were collected using a personal information form, the personal safety questionnaire (PSQ), and the parental perception questionnaire (PPQ).

Personal information form: The form was designed by the researcher to collect demographic information about the participating parents and children.

PSQ: The questionnaire was developed by Wurtele et al. to evaluate children’s knowledge about sexual abuse in 1992 [20]. The questionnaire consists of 11 items in a three-point Likert-type format, where each correct answer is scored as 1 point (with total scores ranging from 0 to 11). Children are asked to respond to each question by saying “yes”, “no”, or “I do not know”. The blind back-translation process was completed, and prior to administration, expert opinions were obtained from five academicians. The two-week test re-test reliability (based on pre- and post-test scores) was 0.56 (P<0.01), and the total correlation coefficient for the PSQ was 0.52 (P<0.001).

PPQ: The instrument was developed by Wurtele et al. [20] in 1992 and adapted to Turkish by Yalın et al. in 1995 [21]. The questionnaire was translated into Turkish by three faculty members, who are proficient in English, and it was subsequently administered to ten parents for feedback. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: The first part, which teaches concepts related to sexual abuse, included 25 items; the second part, which addresses the CSA prevention program, included eight items; and the third part, which focuses on the need for a physical protection program, included six items. It is scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “absolutely disagree” to “absolutely agree”.

Procedure

Before the research, necessary permissions were obtained for the use of questionnaires. Then, we visited all the private preschools in the Bağlıca district and explained the purpose of our research to the preschool principals. Besides, an information note about the research and the implementation schedule was sent to the parents. A total of 108 parents from three preschools volunteered to participate in the program.

The parents from three preschools gathered on Fridays and Saturdays. Each session lasted about 40-60 minutes. The first week included an introduction, an explanation of the research purpose, expectations, and the administration of the PPQ. The parents informed their children about the PSQ, and their consent was obtained. Following the program’s first session, the researcher interviewed every volunteer child and administered the PSQ on Monday. In addition to obtaining family consent, the researcher also secured consent from the children.

The second week, when 108 parents began the CSA prevention program, lasted four weeks. After the program was completed, the PSQ was re-applied to children. A closing meeting was held with the parents, and the PPQ was re-administered to the parents.

Content of the prevention program

The CSA prevention program is an educational program developed by the researcher. I have worked with children who were victims of sexual abuse for six years and have received training on this issue. Additionally, I have conducted seminars on sexual abuse prevention. In preparing the educational program, I utilized health belief theory, causal behavior theory, social learning theory, and previously developed educational programs [17, 22]. Before the implementation of the educational program, expert opinions were also obtained.

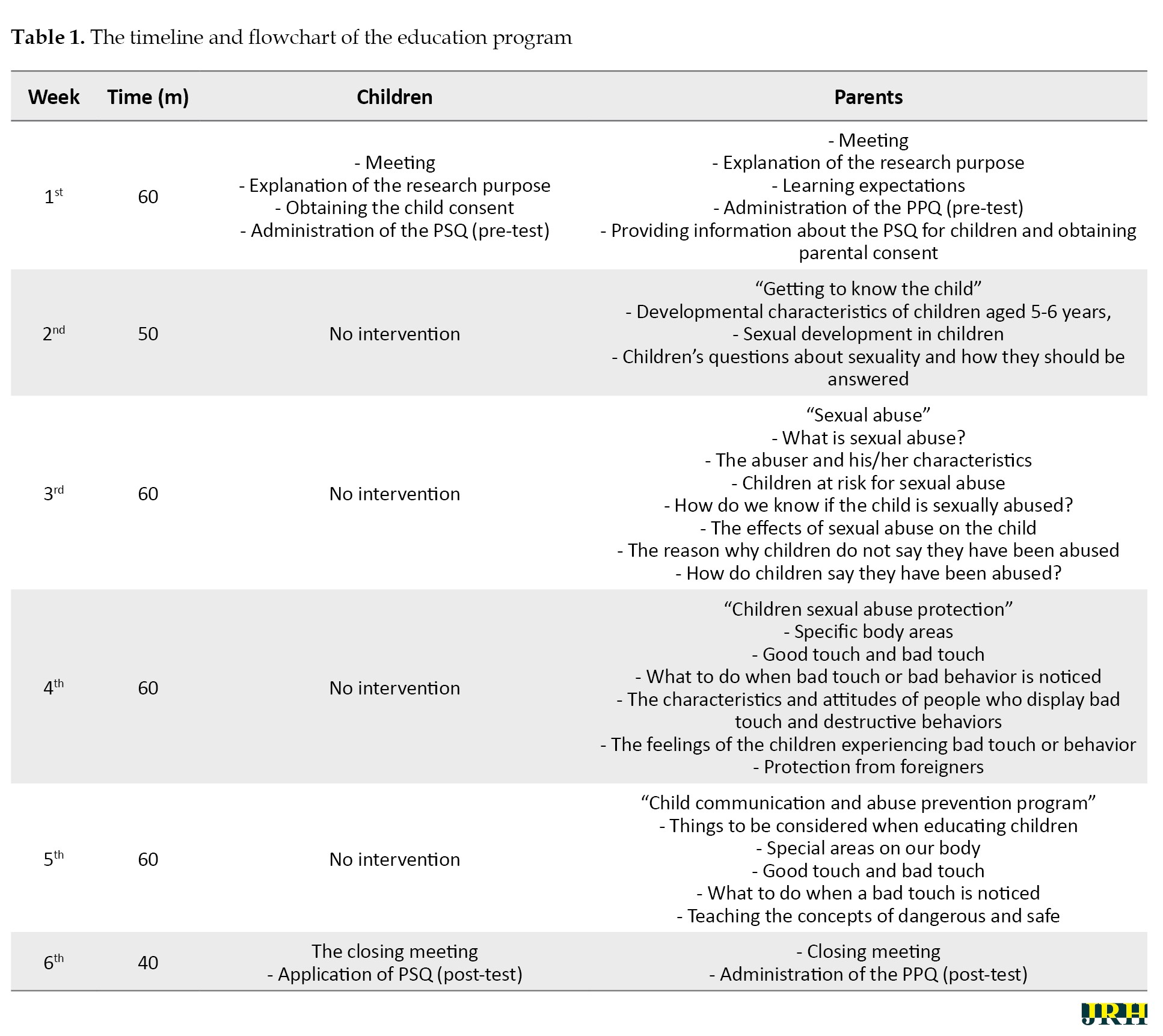

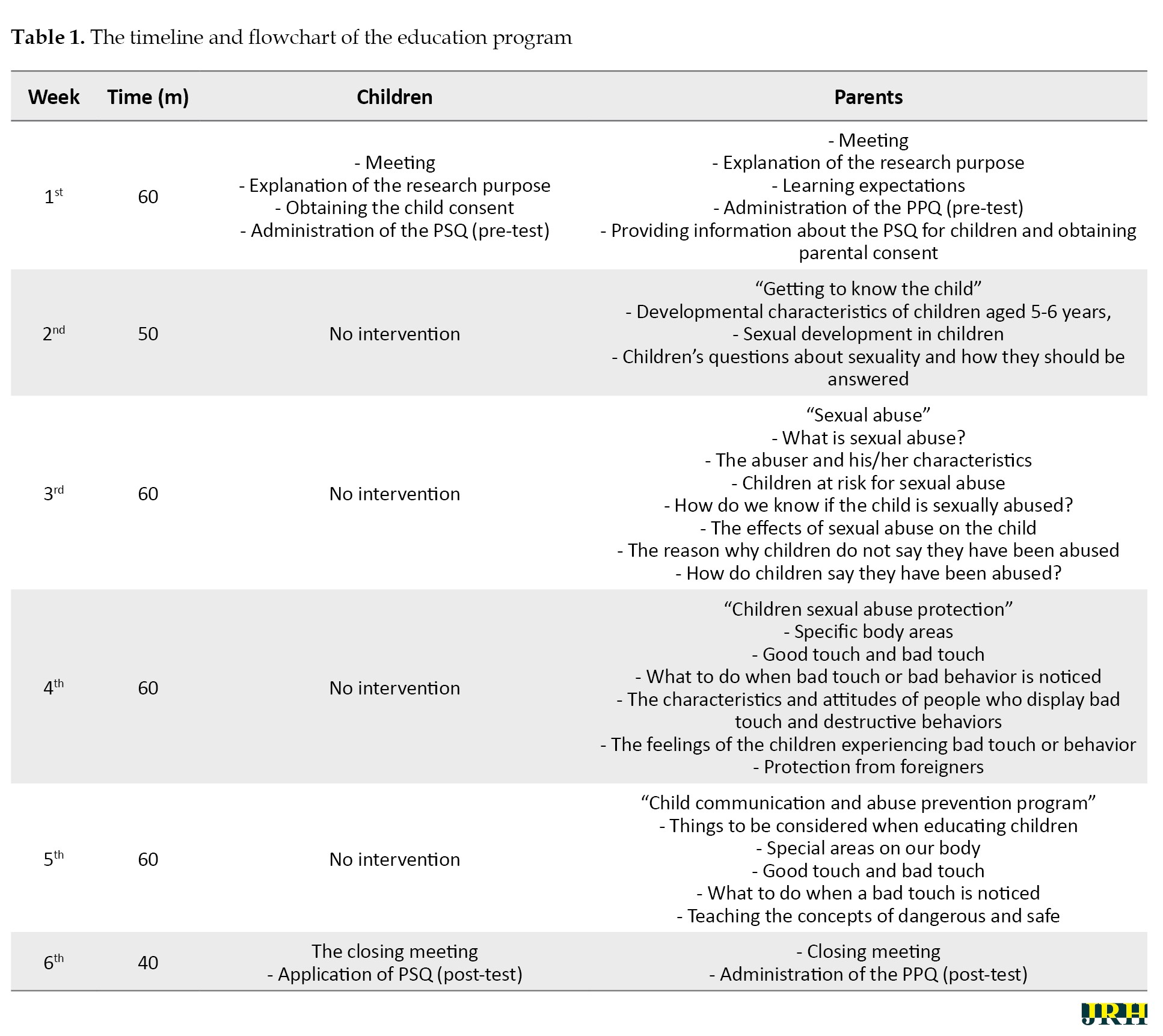

The educational program was implemented for four weeks. The main topics included getting to know the child, sexual abuse, CSA protection, child communication, and abuse prevention programs. Each main topic also included sub-topics. The timeline and flowchart of the educational program are given in Table 1.

The educational topics are explained in detail in the flowchart. The Kiko Handbook, prepared by the Council of Europe in 2013 for families experiencing communication problems with their children, was used as an additional resource.

Data collection and analyses

The study data were collected in January 2021. Pre-tests were applied to parents and children between January 18 and 24, 2020. Post-tests were administered to parents and children between February 22 and 28, 2021. The details are as follows:

First, the PPQ was administered to the parents, and then the CSA prevention program was conducted over four weeks. After the educational program was completed, the PPQ was re-administered.

The PSQ was applied to the children before and after the parent education program. The research aimed to investigate whether the parent education program raised children’s awareness and knowledge of sexual abuse. Therefore, no intervention was made with the children.

A paired-sample t-test was performed to measure the significance of the difference between the parents’ pre- and post-test scores. SPSS software, version 22, was used to analyze the data.

Results

The sample consisted of 100 mothers and 8 fathers. The parents’ ages ranged from 28 to 35 years. All participating parents held an undergraduate degree and were employed in various professions, including officer, lawyer, accountant, industrial engineer, pharmacist, doctor, architect, social worker, chemist, nutritionist, writer, police officer, teacher, computer specialist, nurse, and construction engineer.

The children were the firstborn in their families, with 46 children aged five and 63 children aged six. Since one parent had twins, the total number of children was 109, comprising 44 boys and 64 girls.

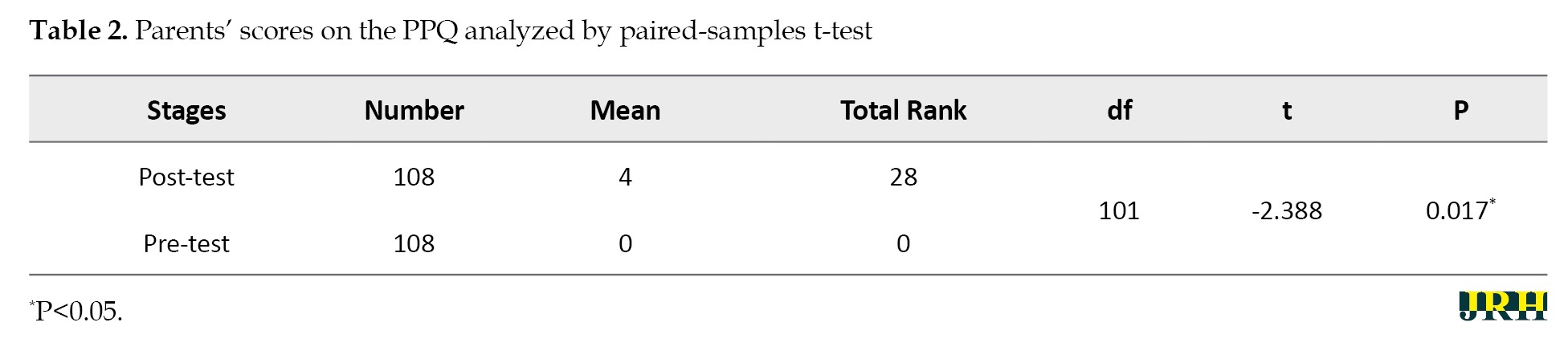

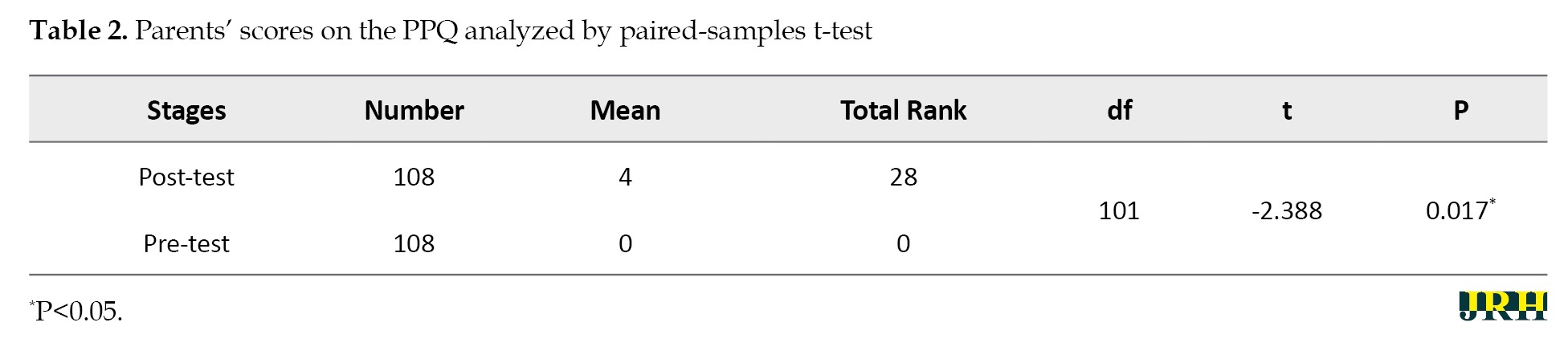

The PPQ scores applied to parents before and after the CSA prevention program are shown in Table 2.

A significant difference was found between the parents’ pre- and post-test scores before and after the educational program (4.00, P<0.05). When the mean and total ranks were taken into consideration, the difference observed was in opposing ranks. Therefore, it can be said that the CSA prevention program positively changed parents’ thoughts.

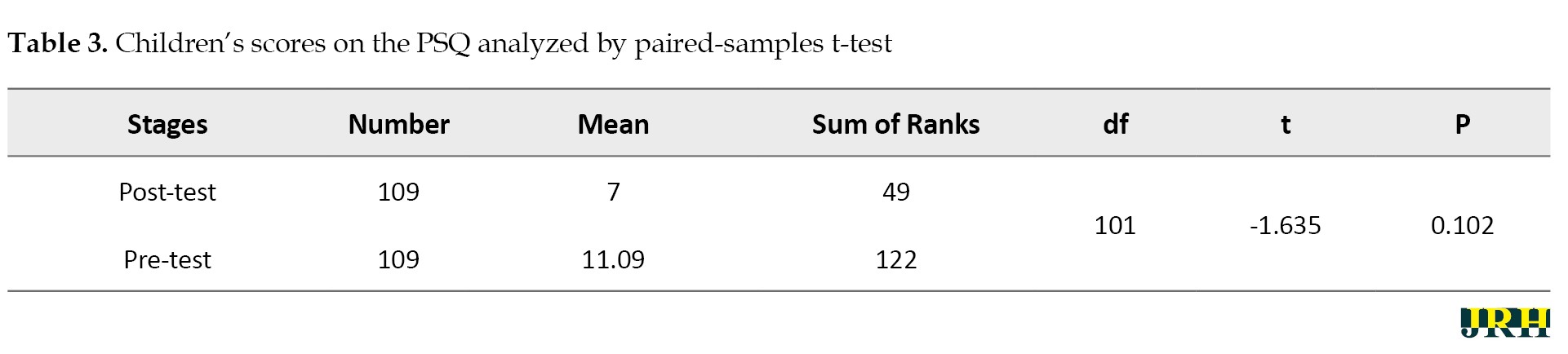

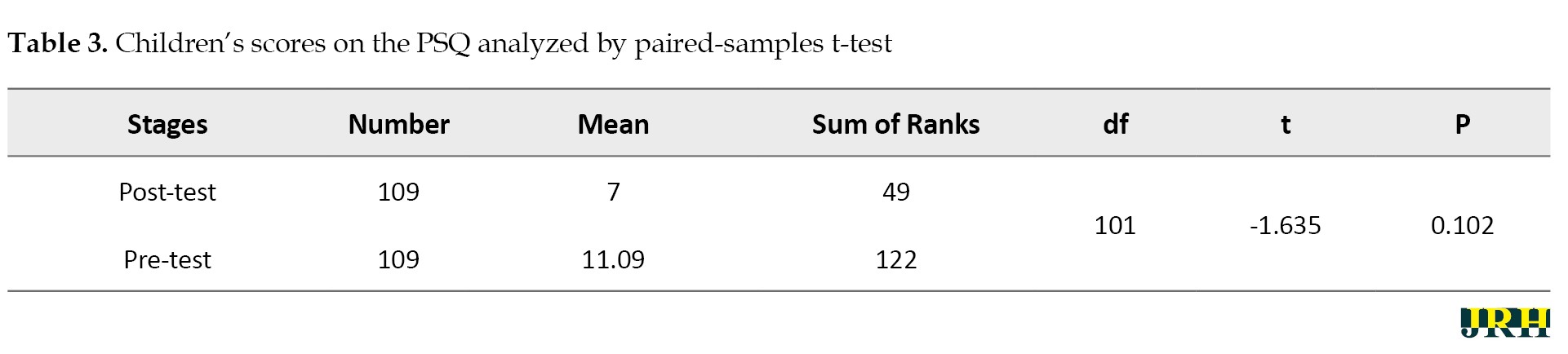

The PSQ scores applied to the children before and after the parent program are shown in Table 3.

There was no significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of children. Additionally, there was a significant increase in positive ranks, but it was not statistically significant. Thus, it can be inferred that the CSA prevention program positively impacted the parents but not the children.

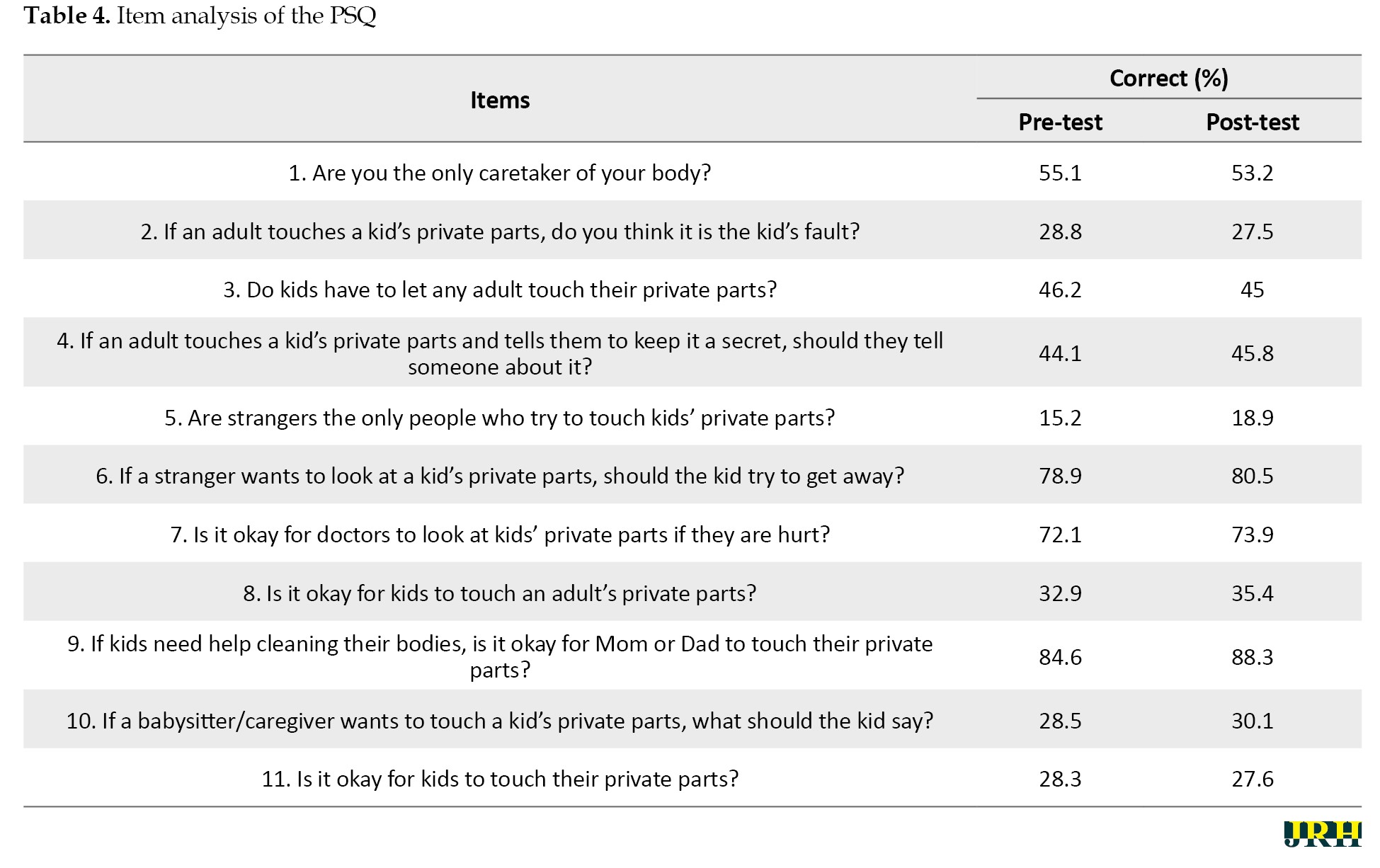

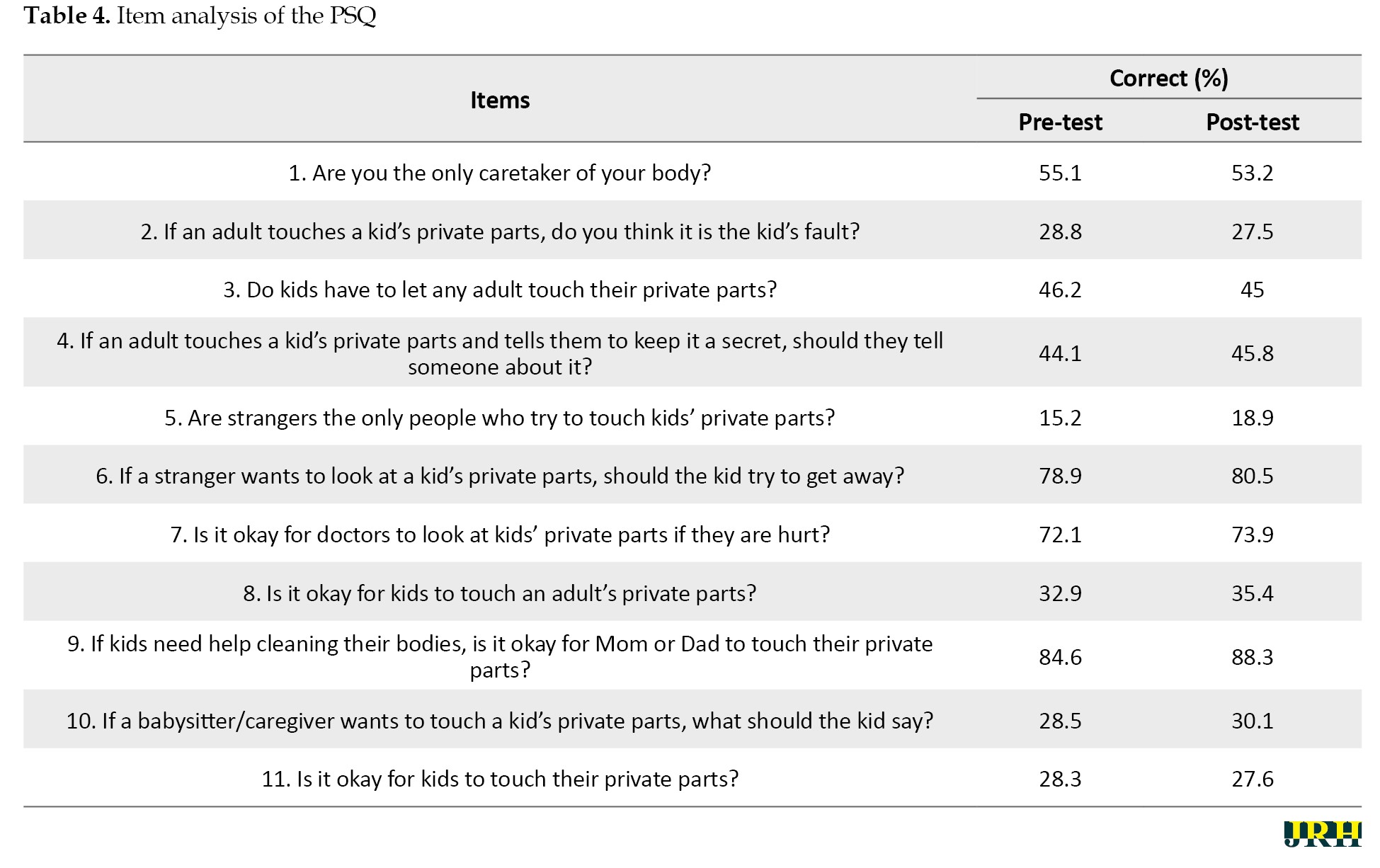

Table 4 presents the comparisons of the PPQ pre- and post-test items.

The children’s correct responses to the PSQ are summarized in Table 4. Preschool children lacked knowledge about CSA. No child answered all items on the PSQ correctly. Besides, almost 70% of the children thought that the abuse was their fault (item 2), and half of them believed that touching their private parts was acceptable (item 3). Only 18.9% knew that if the perpetrator told them to keep it a secret, they should tell someone (item 4). Similarly, 35.4% believed that any adult could touch their private parts (item 8). Also, 80.5% knew that if a stranger wanted to look at their private areas, they should run away (item 6), and for 73.9%, it was appropriate for doctors to touch their private parts (item 7). The majority thought that only foreigners tried to touch their private parts (item 5). In addition, approximately 70% of children believed that it was acceptable for the caregiver to touch their private parts (item 10). In brief, it can be suggested that the children had low levels of knowledge about CSA (49±7).

Discussion

This research aimed to reveal whether the parent CSA prevention program improves children’s knowledge of abuse. The study results showed that the program was effective in raising parents’ awareness. After the program, parents’ knowledge and attitudes toward providing sexual education and addressing abuse significantly improved. Many studies have found that such educational programs effectively increase parents’ knowledge of sexual abuse and enhance their behavior [23, 24]. However, although the results were positive for the parents, no improvement was observed in children’s knowledge levels. This may stem from the fact that the children’s knowledge levels were measured by using their questionnaire responses, rather than through direct participation in any program or intervention. Therefore, it is suggested to prepare a sexual abuse prevention program, especially for preschool children. Several studies have shown that sexual abuse prevention training makes essential contributions to the awareness of both children and adults [25, 26].

It was observed that the children generally responded with “yes” and “I do not know”. For example, when asked, “Are strangers the only people who try to touch kids’ private parts?” most children answered “Yes!” or “Um… I do not know”. The children who responded more clearly and comfortably during the pre-test exhibited hesitation in the post-testIt is thought that the parent program led to confusion among the children. In addition to the dilemma that they experienced in answering the questions, the children struggled to explain how to distinguish potential abusers from people they trust. For instance, when asked, “Do kids have to let any adult touch their private parts?” they mostly approved of being touched by their parents and doctors. However, they asked additional questions, such as “Is my caregiver too?”, “Is my grandmother too?”, “My aunt too?”, “My teacher too?”. Children’s knowledge levels regarding CSA were low. Our results align with the findings of other studies [27, 28]. Preschool children’s knowledge of sexual abuse can be increased through awareness-raising activities [29]. It was found that the parent education program did not affect children’s knowledge levels. Therefore, education programs should be delivered directly to children. Children who received sexual abuse protection training were more competent in recognizing appropriate and inappropriate touches by adults and applying personal safety skills than children who were not trained [30]. Children especially should learn that someone they know can be a potential perpetrator.

However, the findings did not support the hypothesis that the sexual abuse prevention parent program increases children’s sexual abuse knowledge levels. The given program, which improved parents’ knowledge, had no effect on children. Jin et al. [31] reported that parents’ knowledge of sexual abuse reinforced children’s ability to protect themselves from sexual abuse. We found a significant change in the sexual abuse knowledge of the parents, but not in children. As emphasized in the literature, parents are the primary agents for protecting children [32], even if the abusers sometimes can be family members [33]. In this sense, the PPQ was administered to measure the awareness of protection against sexual abuse. The aim was also to ensure that parents had information about CSA, could identify the signs of sexual abuse, and prevent any harmful incidents by educating their children. Burgess and Wurtele [34] stated that parents generally recognize that their children are at risk and take supportive measures to protect them. According to Berrick and Barth [35], CSA prevention programs have promising effects on raising awareness and promoting protective behavior. Additionally, Kenny and Wurtele [36] stress the importance of providing sexual education to children and teaching the medical names of genitals.

The CSA prevention interventions should be implemented before the risk of sexual abuse occurs [37-39]. Although we did not observe a meaningful difference in the knowledge levels of children regarding sexual abuse, there was a notable change in parents’ perceptions. This research would significantly contribute to awareness-raising activities for parents.

We found no significant difference between the children’s pre- and post-test mean scores, which was a remarkable finding and may result from the fact that children did not receive a formal abuse prevention program. It is still disputable whether sexual abuse prevention programs are appropriate for small kids due to their cognitive development characteristics [40-42]. As a result of the meta-analysis on children aged five and under by Rispens et al. [43], sexual abuse prevention programs positively affected young children. It was also found that the prevention program yielded the most meaningful results in the five-year age group. Wurtele [11] emphasized the importance of integrating sexual abuse prevention programs with other learning subjects in the preschool education curriculum, which is believed to enhance the sustainability of the program.

Conclusion

In our study, the educational program did not appear to cause any change in the knowledge levels of the children, although it created a significant difference in the parents. It was concluded that it is important to conduct activities directly with children to help them develop skills to protect themselves from sexual abuse. For this reason, different activities can be implemented for children, including games, books, cartoons, and theatre shows. It is also believed that, as the primary caregivers, parents who have the correct information about protection from sexual abuse may develop an awareness of abuse prevention, and inform and support their children accordingly. Thus, it can be suggested that education programs, seminars, and workshops for parents can effectively raise knowledge and awareness to prevent CSA.

Since sexual abuse is a complicated social issue, regular participation in educational programs was low. Therefore, it is recommended to prepare different sources for parents and child-friendly teaching methods, such as illustrated books, videos, songs, and animations. Such sources help reduce their anxiety and make education engaging while teaching children.

Sexual abuse protection should not be the responsibility of only children. The acquisition of the necessary protection skills should be integrated into formal education. Besides, communities and other cultural and social institutions should act together and follow the ecological theory. In other words, sexual abuse prevention interventions should cover the children, parents, professionals, and the public.

Other strengths of this study include the use of parent and child self-report measures, the involvement of parents in the training program, the focus on whether the development of parents’ knowledge and awareness has an impact on children, the importance of training delivered directly to children, and the careful approach to data analysis.

Although the study provided important findings, there are limitations. Firstly, the sample size can be considered relatively small, which limits the power of the analyses. Further research on these issues is therefore needed to increase the generalisability of the findings. However, this study can only be seen as a preliminary examination of an issue that requires further research. In addition, other studies can implement educational programs for children and incorporate the results of the analysis. In addition, as the study was quasi-experimental, it is not possible to draw causal conclusions from these results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was carried out following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Spanish Society of Psychology. Ethical approval was provided by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences University Hamidiye, Istanbul, Turkey (No.: 20/472, date: 08.01.2021).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all the children and their parents who participated in the research.

References

Child sexual abuse (CSA) refers to the involvement of a developmentally unready child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully understand or accept, which violates laws or social taboos. Perpetrators of CSA may be adults with specific authority or responsibility for the victim and other children [1]. In the broadest sense, CSA describes any attempt by an adult to exploit a child for personal satisfaction [1]. The most critical factors in CSA are children’s inability to recognize the sexual abuse behaviors and the lack of decision-making skills [2]. The United Nations convention on the rights of the children defines people under 18 as children [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) [4] reported that there were approximately 2.3 billion children in the world in 2017, and 12% were exposed to sexual abuse in the same year [5]. Therefore, CSA is a global public health problem [6]. CSA is associated with multiple negative outcomes, such as mental health issues (e.g. anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and physical health problems (e.g. infectious diseases, musculoskeletal pain, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic fatigue, headaches, and cardio-respiratory problems) [7, 8]. It is prevalent in all national and ethnic origins [9, 10].

Identifying CSA is challenging because it can persist for several years [11], and it often remains undetected unless children disclose that they have been abused [12]. Besides, CSA includes a wide range of sexual behaviors, from exhibitionism to physical contact, which complicates confirmation of abuse [13]. According to the Human Rights Association (IHD) [14], sexual abuse victims are at different stages of cognitive and language development, which may be one of the reasons behind children’s silence and doubts about disclosing sexual abuse. Therefore, it is essential to distinguish between normal and abnormal sexual behaviors and have accurate information about the physical symptoms of sexual abuse [15, 16]. CSA prevention programs have been implemented for two decades [17].

Families play a significant role in the prevention of CSA, although they often have concerns about delivering such education. CSA is a major public health issue that can have long-lasting psychological, emotional, and physical effects on victims. Understanding how to effectively educate parents about preventing such abuse is crucial. Üstündağ et al. [18] found that sexual abuse education positively enhanced parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Despite the availability of various CSA prevention programs, there is limited research on the direct impact of educating parents on their children’s knowledge about abuse. This study addresses this gap by evaluating whether CSA prevention education for parents increases the knowledge levels of children. Accordingly, the causal hypothesis was established: “Parent program improves children’s awareness and knowledge of sexual abuse”. In line with the purpose of the research, the following questions were posed:

1. Does a CSA prevention program make a significant difference in the pre- and post-test scores of parents’ perceptions of sexual abuse?

2. Is there a significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores regarding sexual abuse knowledge and awareness levels?

3. What is the sexual abuse knowledge level of children?

Methods

Research design

This quantitative quasi-experimental study employed the pre-test and post-test design to establish a cause-and-effect relationship [19].

Participants

The study was carried out in the Bağlıca district of Ankara. Since most schools were closed due to the pandemic, only 3 of 12 preschools in the Bağlıca district participated in the study. A total of 229 parents were randomized across the three preschools, of whom 152 volunteered for the study. However, some parents withdrew from the study because they did not want to continue the program or complete the final test. Similarly, some children left the study as they did not wish to complete the final test. Finally, 108 parents and 109 children were included in the study. There was one parent per family. The ages of the children ranged from five to six. Participation in the study was voluntary and informed consent forms were also obtained from the parents.

The inclusion criteria for parents were having a child between the ages of 3 and 6, attending a preschool in the Bağlıca district, volunteering to participate in the study, and attending the education program regularly. Inappropriate and improperly completed scales were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, parents who did not attend the education program regularly were also excluded from the study.

There were 100 mothers and eight fathers in the sample. The parents’ ages ranged from 28 to 35 years. All the parents had an undergraduate degree and were employed in different professions, such as officer, lawyer, accountant, industrial engineer, pharmacist, doctor, architect, social worker, chemist, nutritionist, writer, police officer, teacher, computer specialist, nurse, and construction engineer. The children were the firstborn in their families, with 46 children aged five and 63 children aged six. Since one parent had twins, the total number of children was 109, comprising 44 boys and 64 girls.

Data collection tools

Data were collected using a personal information form, the personal safety questionnaire (PSQ), and the parental perception questionnaire (PPQ).

Personal information form: The form was designed by the researcher to collect demographic information about the participating parents and children.

PSQ: The questionnaire was developed by Wurtele et al. to evaluate children’s knowledge about sexual abuse in 1992 [20]. The questionnaire consists of 11 items in a three-point Likert-type format, where each correct answer is scored as 1 point (with total scores ranging from 0 to 11). Children are asked to respond to each question by saying “yes”, “no”, or “I do not know”. The blind back-translation process was completed, and prior to administration, expert opinions were obtained from five academicians. The two-week test re-test reliability (based on pre- and post-test scores) was 0.56 (P<0.01), and the total correlation coefficient for the PSQ was 0.52 (P<0.001).

PPQ: The instrument was developed by Wurtele et al. [20] in 1992 and adapted to Turkish by Yalın et al. in 1995 [21]. The questionnaire was translated into Turkish by three faculty members, who are proficient in English, and it was subsequently administered to ten parents for feedback. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: The first part, which teaches concepts related to sexual abuse, included 25 items; the second part, which addresses the CSA prevention program, included eight items; and the third part, which focuses on the need for a physical protection program, included six items. It is scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “absolutely disagree” to “absolutely agree”.

Procedure

Before the research, necessary permissions were obtained for the use of questionnaires. Then, we visited all the private preschools in the Bağlıca district and explained the purpose of our research to the preschool principals. Besides, an information note about the research and the implementation schedule was sent to the parents. A total of 108 parents from three preschools volunteered to participate in the program.

The parents from three preschools gathered on Fridays and Saturdays. Each session lasted about 40-60 minutes. The first week included an introduction, an explanation of the research purpose, expectations, and the administration of the PPQ. The parents informed their children about the PSQ, and their consent was obtained. Following the program’s first session, the researcher interviewed every volunteer child and administered the PSQ on Monday. In addition to obtaining family consent, the researcher also secured consent from the children.

The second week, when 108 parents began the CSA prevention program, lasted four weeks. After the program was completed, the PSQ was re-applied to children. A closing meeting was held with the parents, and the PPQ was re-administered to the parents.

Content of the prevention program

The CSA prevention program is an educational program developed by the researcher. I have worked with children who were victims of sexual abuse for six years and have received training on this issue. Additionally, I have conducted seminars on sexual abuse prevention. In preparing the educational program, I utilized health belief theory, causal behavior theory, social learning theory, and previously developed educational programs [17, 22]. Before the implementation of the educational program, expert opinions were also obtained.

The educational program was implemented for four weeks. The main topics included getting to know the child, sexual abuse, CSA protection, child communication, and abuse prevention programs. Each main topic also included sub-topics. The timeline and flowchart of the educational program are given in Table 1.

The educational topics are explained in detail in the flowchart. The Kiko Handbook, prepared by the Council of Europe in 2013 for families experiencing communication problems with their children, was used as an additional resource.

Data collection and analyses

The study data were collected in January 2021. Pre-tests were applied to parents and children between January 18 and 24, 2020. Post-tests were administered to parents and children between February 22 and 28, 2021. The details are as follows:

First, the PPQ was administered to the parents, and then the CSA prevention program was conducted over four weeks. After the educational program was completed, the PPQ was re-administered.

The PSQ was applied to the children before and after the parent education program. The research aimed to investigate whether the parent education program raised children’s awareness and knowledge of sexual abuse. Therefore, no intervention was made with the children.

A paired-sample t-test was performed to measure the significance of the difference between the parents’ pre- and post-test scores. SPSS software, version 22, was used to analyze the data.

Results

The sample consisted of 100 mothers and 8 fathers. The parents’ ages ranged from 28 to 35 years. All participating parents held an undergraduate degree and were employed in various professions, including officer, lawyer, accountant, industrial engineer, pharmacist, doctor, architect, social worker, chemist, nutritionist, writer, police officer, teacher, computer specialist, nurse, and construction engineer.

The children were the firstborn in their families, with 46 children aged five and 63 children aged six. Since one parent had twins, the total number of children was 109, comprising 44 boys and 64 girls.

The PPQ scores applied to parents before and after the CSA prevention program are shown in Table 2.

A significant difference was found between the parents’ pre- and post-test scores before and after the educational program (4.00, P<0.05). When the mean and total ranks were taken into consideration, the difference observed was in opposing ranks. Therefore, it can be said that the CSA prevention program positively changed parents’ thoughts.

The PSQ scores applied to the children before and after the parent program are shown in Table 3.

There was no significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of children. Additionally, there was a significant increase in positive ranks, but it was not statistically significant. Thus, it can be inferred that the CSA prevention program positively impacted the parents but not the children.

Table 4 presents the comparisons of the PPQ pre- and post-test items.

The children’s correct responses to the PSQ are summarized in Table 4. Preschool children lacked knowledge about CSA. No child answered all items on the PSQ correctly. Besides, almost 70% of the children thought that the abuse was their fault (item 2), and half of them believed that touching their private parts was acceptable (item 3). Only 18.9% knew that if the perpetrator told them to keep it a secret, they should tell someone (item 4). Similarly, 35.4% believed that any adult could touch their private parts (item 8). Also, 80.5% knew that if a stranger wanted to look at their private areas, they should run away (item 6), and for 73.9%, it was appropriate for doctors to touch their private parts (item 7). The majority thought that only foreigners tried to touch their private parts (item 5). In addition, approximately 70% of children believed that it was acceptable for the caregiver to touch their private parts (item 10). In brief, it can be suggested that the children had low levels of knowledge about CSA (49±7).

Discussion

This research aimed to reveal whether the parent CSA prevention program improves children’s knowledge of abuse. The study results showed that the program was effective in raising parents’ awareness. After the program, parents’ knowledge and attitudes toward providing sexual education and addressing abuse significantly improved. Many studies have found that such educational programs effectively increase parents’ knowledge of sexual abuse and enhance their behavior [23, 24]. However, although the results were positive for the parents, no improvement was observed in children’s knowledge levels. This may stem from the fact that the children’s knowledge levels were measured by using their questionnaire responses, rather than through direct participation in any program or intervention. Therefore, it is suggested to prepare a sexual abuse prevention program, especially for preschool children. Several studies have shown that sexual abuse prevention training makes essential contributions to the awareness of both children and adults [25, 26].

It was observed that the children generally responded with “yes” and “I do not know”. For example, when asked, “Are strangers the only people who try to touch kids’ private parts?” most children answered “Yes!” or “Um… I do not know”. The children who responded more clearly and comfortably during the pre-test exhibited hesitation in the post-testIt is thought that the parent program led to confusion among the children. In addition to the dilemma that they experienced in answering the questions, the children struggled to explain how to distinguish potential abusers from people they trust. For instance, when asked, “Do kids have to let any adult touch their private parts?” they mostly approved of being touched by their parents and doctors. However, they asked additional questions, such as “Is my caregiver too?”, “Is my grandmother too?”, “My aunt too?”, “My teacher too?”. Children’s knowledge levels regarding CSA were low. Our results align with the findings of other studies [27, 28]. Preschool children’s knowledge of sexual abuse can be increased through awareness-raising activities [29]. It was found that the parent education program did not affect children’s knowledge levels. Therefore, education programs should be delivered directly to children. Children who received sexual abuse protection training were more competent in recognizing appropriate and inappropriate touches by adults and applying personal safety skills than children who were not trained [30]. Children especially should learn that someone they know can be a potential perpetrator.

However, the findings did not support the hypothesis that the sexual abuse prevention parent program increases children’s sexual abuse knowledge levels. The given program, which improved parents’ knowledge, had no effect on children. Jin et al. [31] reported that parents’ knowledge of sexual abuse reinforced children’s ability to protect themselves from sexual abuse. We found a significant change in the sexual abuse knowledge of the parents, but not in children. As emphasized in the literature, parents are the primary agents for protecting children [32], even if the abusers sometimes can be family members [33]. In this sense, the PPQ was administered to measure the awareness of protection against sexual abuse. The aim was also to ensure that parents had information about CSA, could identify the signs of sexual abuse, and prevent any harmful incidents by educating their children. Burgess and Wurtele [34] stated that parents generally recognize that their children are at risk and take supportive measures to protect them. According to Berrick and Barth [35], CSA prevention programs have promising effects on raising awareness and promoting protective behavior. Additionally, Kenny and Wurtele [36] stress the importance of providing sexual education to children and teaching the medical names of genitals.

The CSA prevention interventions should be implemented before the risk of sexual abuse occurs [37-39]. Although we did not observe a meaningful difference in the knowledge levels of children regarding sexual abuse, there was a notable change in parents’ perceptions. This research would significantly contribute to awareness-raising activities for parents.

We found no significant difference between the children’s pre- and post-test mean scores, which was a remarkable finding and may result from the fact that children did not receive a formal abuse prevention program. It is still disputable whether sexual abuse prevention programs are appropriate for small kids due to their cognitive development characteristics [40-42]. As a result of the meta-analysis on children aged five and under by Rispens et al. [43], sexual abuse prevention programs positively affected young children. It was also found that the prevention program yielded the most meaningful results in the five-year age group. Wurtele [11] emphasized the importance of integrating sexual abuse prevention programs with other learning subjects in the preschool education curriculum, which is believed to enhance the sustainability of the program.

Conclusion

In our study, the educational program did not appear to cause any change in the knowledge levels of the children, although it created a significant difference in the parents. It was concluded that it is important to conduct activities directly with children to help them develop skills to protect themselves from sexual abuse. For this reason, different activities can be implemented for children, including games, books, cartoons, and theatre shows. It is also believed that, as the primary caregivers, parents who have the correct information about protection from sexual abuse may develop an awareness of abuse prevention, and inform and support their children accordingly. Thus, it can be suggested that education programs, seminars, and workshops for parents can effectively raise knowledge and awareness to prevent CSA.

Since sexual abuse is a complicated social issue, regular participation in educational programs was low. Therefore, it is recommended to prepare different sources for parents and child-friendly teaching methods, such as illustrated books, videos, songs, and animations. Such sources help reduce their anxiety and make education engaging while teaching children.

Sexual abuse protection should not be the responsibility of only children. The acquisition of the necessary protection skills should be integrated into formal education. Besides, communities and other cultural and social institutions should act together and follow the ecological theory. In other words, sexual abuse prevention interventions should cover the children, parents, professionals, and the public.

Other strengths of this study include the use of parent and child self-report measures, the involvement of parents in the training program, the focus on whether the development of parents’ knowledge and awareness has an impact on children, the importance of training delivered directly to children, and the careful approach to data analysis.

Although the study provided important findings, there are limitations. Firstly, the sample size can be considered relatively small, which limits the power of the analyses. Further research on these issues is therefore needed to increase the generalisability of the findings. However, this study can only be seen as a preliminary examination of an issue that requires further research. In addition, other studies can implement educational programs for children and incorporate the results of the analysis. In addition, as the study was quasi-experimental, it is not possible to draw causal conclusions from these results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was carried out following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Spanish Society of Psychology. Ethical approval was provided by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences University Hamidiye, Istanbul, Turkey (No.: 20/472, date: 08.01.2021).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all the children and their parents who participated in the research.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidenc. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Link]

- McTavish JR, McKee C, Tanaka M, MacMillan HL. Child welfare reform: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14071. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph192114071] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Unicef. Convention on the Rights of the Child: For every child, every right [Internet]. 1989 [Updated January 5]. Available from: [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Child maltreatment [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 2024 November5]. Available from: [Link]

- UNICEF. Sexual violence [Internet]. 2019 [Updated 2024 October 1]. Available from: [Link]

- Collin-Vézina D, Daigneault I, Hébert M. Lessons learned from child sexual abuse research: Prevalence, outcomes, and preventive strategies. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2013; 7(1):22. [DOI:10.1186/1753-2000-7-22] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Brennenstuhl S, Frank J. The association between childhood physical abuse and heart disease in adulthood: Findings from a representative community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010; 34(9):689-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.005] [PMID]

- Maalouf O, Daigneault I, Dargan S, McDuff P, Frappier JY. Relationship between child sexual abuse, psychiatric disorders and infectious diseases: A matched-cohort study. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2020; 29(7):749-68. [DOI:10.1080/10538712.2019.1709242] [PMID]

- Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health. 2013; 58(3):469-83. [DOI:10.1007/s00038-012-0426-1] [PMID]

- Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse: A continuation of Finkelhor (1994). Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009; 33(6):331-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.007] [PMID]

- Wurtele SK. Preventing sexual abuse of children in the twenty-first century: Preparing for challenges and opportunities. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2009; 18(1):1-18. [DOI:10.1080/10538710802584650] [PMID]

- Finkelhor D. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994; 18(5):409-17. [DOI:10.1016/0145-2134(94)90026-4] [PMID]

- Aksel ES, Yılmaz Irmak T. [Teachers’ knowledge and experience about child sexual abuse (Turkish)]. Ege Journal of Education. 2015; 16(2):373-91. [DOI:10.12984/eed.60194]

- İHD–Human Rights Association. Preventing child neglect and abuse (educational guide for teachers and families) (Turkish) [Internet]. 2007 [Updated 2007 November 27]. Available from: [Link]

- Anderson JF, Mangels NJ, Langsam A. Child sexual abuse: A public health issue. Criminal Justice Studies. 2004; 17(1):107-26. [DOI:10.1080/08884310420001679386]

- Kogan SM. Disclosing unwnated sexual experiences: Results from a national sample of adolescent women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004; 28(2):147-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.014] [PMID]

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC). Child Sexual abuse prevention overview. Harrisburg: National Sexual Violence Resource Center; 2011. [Link]

- Üstündağ A, Şenol FB, Mağden D. [Determining and raising the awareness of parents about child abuse (Turkish)]. Hacettepe University Faculty of Health Sciences Journal. 2015; 1(2):212-27. [Link]

- Erkus A. Scientific research process for behavioral sciences. Ankara: Seçkin Publishing, 2017. [Link]

- Wurtele SK, Gillispie EI, Currier LL, Franklin CF. A comparison of teachers vs. parents as instructors of a personal safety program for preschoolers. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992; 16(1):127-37. [DOI:10.1016/0145-2134(92)90013-H] [PMID]

- Yalın A, Kerimoğlu E, Erman F. [Preventive educational studies against sexual harassment and abuse for children (Turkish)]. Turkish Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 1995; 2(1):19-27. [Link]

- Koruncuk. [Methods of recognition and prevention of child health (Turkish)]. İstanbul: Koruncuk; 2018. [Link]

- Hiller HH. Required reading: Sociology’s most influential books. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 2001; 37(1):85-6. [DOI:10.1002/1520-6696(200124)37:1<85::AID-JHBS18>3.0.CO;2-%23]

- Khanjari S, Modabber M, Rahmati M, Haghani H. [Knowledge, attitudes and practices among parents of school-age children after child sexual abuse prevention education (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2017; 29(104):17-27. [DOI:10.29252/ijn.29.104.17]

- Navaei M, Akbari-Kamrani M, Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh S, Farid M, Tehranizadeh M. Effect of group counseling on parents' self-efficacy, knowledge, attitude, and communication practice in preventing sexual abuse of children aged 2-6 years: A randomized controlled clinical trial. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery. 2018; 6(4):285-92. [PMID]

- Tutty LM, Aubry D, Velasquez L. The "who do you tell?"™ Child sexual abuse education program: Eight years of monitoring. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2020; 29(1):2-21. [DOI:10.1080/10538712.2019.1663969] [PMID]

- Kızıltepe R, Eslek D, Irmak TY, Güngör D. "I am learning to protect myself with Mika:" A teacher-based child sexual abuse prevention program in Turkey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2022; 37(11-12):NP10220-244. [DOI:10.1177/0886260520986272] [PMID]

- Kenny MC, Wurtele SK, Alonso L. Evaluation of a personal safety program with Latino preschoolers. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2012; 21(4):368-85. [DOI:10.1080/10538712.2012.675426] [PMID]

- Zhang W, Chen J, Feng Y, Li J, Zhao X, Luo X. Young children's knowledge and skills related to sexual abuse prevention: A pilot study in Beijing, China. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013; 37(9):623-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.018] [PMID]

- Zhang H, Shi R, Li Y, Wang Y. Effectiveness of school-based child sexual abuse prevention programs in China: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice. 2021; 31(7):693-705. [DOI:10.1177/10497315211022827]

- Jin Y, Chen J, Yu B. Parental practice of child sexual abuse prevention education in China: Does it have an influence on child’s outcome? Children and Youth Services Review. 2019; 96:64-69. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.029]

- Mlekwa FM, Nyamhanga T, Chalya PL, Urassa D. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of parents on child sexual abuse and its prevention in Shinyanga District, Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research. 2016; 18(4):1-9. [DOI:10.4314/thrb.v18i4.6]

- Pala B, Unalacak M, Unlüoğlu İ. Child maltreatment: Abuse and neglect. Dicle Medical Journal. 2011; 38(1):121-7. [DOI:10.5798/diclemedj.0921.2012.04.0184]

- Burgess ES, Wurtele SK. Enhancing parent-child communication about sexual abuse: A pilot study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998; 22(11):1167-75. [DOI:10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00094-5] [PMID]

- Berrick JD, Barth RP. Child sexual abuse prevention: Research review and recommendations. Social Work Research and Abstracts. 1992; 28(4):6-15. [DOI:10.1093/swra/28.4.6]

- Kenny MC, Wurtele SK. Toward prevention of childhood sexual abuse: Preschoolers’ knowledge of genital body parts. In: Plakhotnik MS, Nielsen SM, editors. Proceedings of the seventh annual college of education research conference: urban and international education section. Miami: Florida International University; 2008. [Link]

- Bolen RM, Lamb JL. Ambivalence of nonoffending guardians after child sexual abuse disclosure. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004; 19(2):185-211. [DOI:10.1177/0886260503260324] [PMID]

- Chen JQ, Chen DG. Awareness of child sexual abuse prevention education among parents of Grade 3 elementary school pupils in Fuxin City, China. Health Education Research. 2005; 20(5):540-7. [DOI:10.1093/her/cyh012] [PMID]

- Prevent Child Abuse America. Preventing child sexual abuse position statement [internet]. 2016 [Updated 21 January 2025]. Avalable from: [Link]

- Kohl J. School-based child sexual abuse prevention programs. Journal Of Family Violence 1993; 8:137-50. [DOI:10.1007/BF00981764]

- Reppucci ND, Haugaard JJ. Prevention of child sexual abuse: Myth or reality? In: Chess S, HertzigME, Chess S, Hertzig ME, editors. Annual progress in child psychiatry and child development 1991. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1991. [Link]

- Webster R. Issues in school-based child sexual abuse prevention. Children & Society 1991; 5(2):146-64. [DOI:10.1111/j.1099-0860.1991.tb00380.x]

- Rispens J, Aleman A, Goudena PP. Prevention of child sexual abuse victimization: A meta-analysis of school programs. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997; 21(10):975-87. [DOI:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00058-6] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2024/06/1 | Accepted: 2024/07/3 | Published: 2025/01/1

Received: 2024/06/1 | Accepted: 2024/07/3 | Published: 2025/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |