Volume 15, Issue 6 (Nov & Dec 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(6): 583-592 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amedu A N, Dwarika V. Traumatic Experiences and Access to Trauma-informed Care Among Undergraduate Students: Evidence From Nigeria. J Research Health 2025; 15 (6) :583-592

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2750-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2750-en.html

1- Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. , amosnnaemeka@gmail.com , aamedu@uj.ac.za

2- Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

2- Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Full-Text [PDF 630 kb]

(426 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2110 Views)

Full-Text: (337 Views)

Introduction

Trauma is a psychological condition resulting from individual experiences of atrocities, abuse, death, disasters, and casualties [1, 2]. Traumatic experiences refer to situations where social, technological, or natural influences significantly impact a student's emotional and physical well-being, leading to disruptions in their social, academic, and mental health [3]. Students’ traumatic experiences entail exposure to emotionally life-threatening situations, such as school shootings, abuse, and kidnapping [3]. Trauma occurs when a student struggles to recognise a safe space within their school environment to process and cope with distressing experiences [4, 5]. These kinds of trauma are common in educational settings and negatively impact their well-being [6]. In Nigeria, students experience traumatic events due to high levels of insecurity, which have grievously disrupted their educational system [7]. Traumatic events have created a state of uncertainty, leading to widespread deaths of students, closure of schools, and devastating impacts on the victims' educational goals [3, 7]. Northern Nigeria is experiencing a surge in terrorist attacks on universities and colleges due to armed conflict between Nigerian security forces and Boko Haram, resulting in deaths and internal displacement [8]. Also, attacks in Kaduna state have resulted in the abduction of 280 students and teachers from two schools [7] and 70 students from Yawuri Government Secondary School in Zamfara [9].

Similarly, in Southern Nigeria, insecurity due to freedom agitators (indigenous people of Biafra (IPOB)) has caused traumatic events due to their clashes with security [10]. In 2021, suspected IPOB members allegedly pursued students from Nkume secondary school during their West African Examination Council (WAEC) exams [9]. Undergraduate students' exposure to traumatic events can negatively impact cognitive skills [11], leading to behavioural issues, like aggression and emotional imbalance, potentially causing suspension [12]. Students who experience emotional stress, threats to life and property, may suffer from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the absence of trauma-informed care (TIC) [5].

TIC emerged in response to the negative effects of trauma on students, especially those with adverse childhood experiences [13]. Trauma-informed school environments help students feel supported and improve their academic success [14]. TIC implementation necessitates school leaders' support, trauma-sensitive teaching methods, positive behaviour responses, policy modifications, teacher training, and collaboration with mental health professionals [15]. Having a trauma-informed environment benefits academic performance [16], but it remains underutilized in higher education [17].

Literature abounds with students’ traumatic experiences. In studies involving traumatized students, approximately 6-12% report symptoms relevant to diagnosing PTSD, while a good number of students [85%] have been through a traumatic event during their stay in school, and 21% of the students have experienced an event during college [18]. The study differs from the current study because it was conducted in the USA and utilized a mixed-methods approach to promote trauma recovery and assist teachers in engaging trauma-affected children. Furthermore, a study reported that students who have suffered trauma will not be capable of dealing effectively with pressures, setbacks, challenges, and adversities in the future [11]. The reviewed study evaluates children's health, behaviour, and academic outcomes, unlike the current study, which explored the experiences of higher education students. A study revealed that 20% of trauma-affected youth exhibit behavioural issues, compared to only 10% without a trauma history [19]. Research shows that individuals with a history of traumatic experiences, including adverse childhood experiences, experience lifelong physical, mental, and emotional effects, potentially leading to complex mental health disorders like PTSD [20].

Concerning TIC, a study reported that trauma-informed awareness increases in knowledge of TIC and trauma-informed educational strategies and the improved ability to support students [21]. The study was not conducted in Nigeria and did not examine the students' experiences of TIC in higher education. A study outlined the rationale for trauma-informed approaches in higher education institutions, emphasising the importance of cultural competency and cultural humility through a literature review approach [22]. However, this study did not explore the lived experiences of higher education students’ access to TIC. Similarly, another study used a literature review lens to explore the incorporation of TIC into school-based programs and reported that some schools have successfully incorporated trauma-informed approaches into adolescent pregnancy prevention programs [12]. The current study focused on the experiences of traumatised students and their access to TIC at Nigerian universities, differing from the review study's objectives.

Research indicates that students frequently experience trauma in primary and secondary schools, but there is limited research on this issue in higher education in Nigeria. The study sought to provide first-hand qualitative evidence on the traumatic experiences students encounter and their access to TIC in Nigerian higher education. It aimed to answer questions about the types of academic and community-based traumatic experiences undergraduate students encounter, as well as whether they have access to TIC. The findings are expected to benefit the academic community and contribute to sustainable development goal 4 (SDG 4), which promotes quality education for all [23]. The results will help school administrators adopt effective support programs for traumatized students.

Methods

Setting and design

The study used a phenomenological qualitative research design to investigate students’ lived and shared academic and community-based traumatic experiences and their access to TIC services. Data were collected between September and November 2024 through interviews. Nigerian universities sampled included the University of Nigeria Nsukka, the University of Lagos, and Usman Danfodiyo University in Sokoto. The University of Nigeria and Lagos have histories of traumatic events, such as sexual abuses and suicidal ideations, while Usman Danfodiyo is located in a terrorist prone zone. Access to the study area was free, as responses were obtained via Zoom and Google Meet.

Participants

The study involved 15 participants recruited through departmental WhatsApp groups, with purposive sampling restricted to students in their penultimate and final years who had experienced traumatic experiences. Participants were invited to the first stage via WhatsApp. In the second stage, participants who shared weeks of traumatic experiences were selected. The third stage involved selecting internet-accessible participants for meetings via Zoom and Google Meet. The aim was to provide an overview of the research and ensure confidentiality, using pseudonyms for anonymity. Finally, 15 participants consented to participate.

Procedures

Two facilitators, Amos Nnaemeka Amedu and Veronica Dwarika, conducted semi-structured interviews through online sessions via Zoom and Google Meet. They hold PhDs in educational psychology and have extensive research expertise in qualitative approaches. The researcher developed an interview guide to promote uniformity and minimise biases. The guide covered primary research questions, open-ended questions, prompts, and follow-up questions. The facilitators underwent a day of training on the interview guide. The interviews were scheduled at participants’ convenience, and there were no right or wrong answers. The questions aim to uncover participants’ lived experiences of trauma and their access to trauma care services. Open-ended questions were used, such as Have you ever encountered any traumatic events? Can you articulate your feelings during that event? Have you ever utilised TIC services? And follow-up questions. The interviews were recorded, with each session lasting between 15 and 25 minutes. Participants’ responses were securely stored on an online platform with a password and pseudonym, providing a user-friendly interface and straightforward data storage, making it an ideal choice for researchers.

Data analysis

The recorded sessions were transcribed verbatim. Two experienced coders, who also facilitated the sessions, carried out the open coding of the transcripts. The researcher met with the coders multiple times to ensure the coding was consistent. After this phase, the researcher reviewed the coding and created initial codebooks, which were combined into a final codebook for axial coding. Frequent meetings between the researcher and coders helped reach a consensus. The coding agreement was measured using Cohen’s kappa, resulting in an 84% agreement rate. A third independent researcher performed axial coding to minimise bias. Thematic analysis was conducted by coders and an independent researcher, who categorized the codes into broader themes. The researcher defined themes, verified transcripts and codes for accuracy, and the lead independent researcher validated them before finalising them.

Results

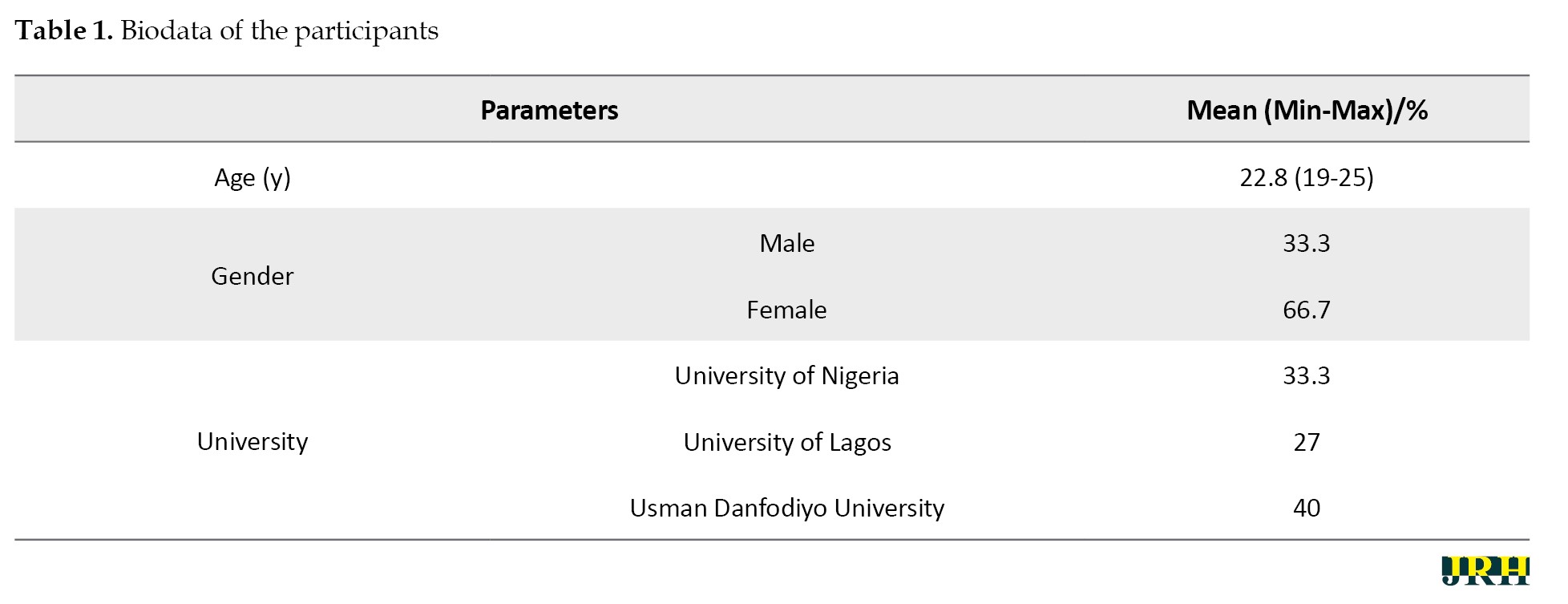

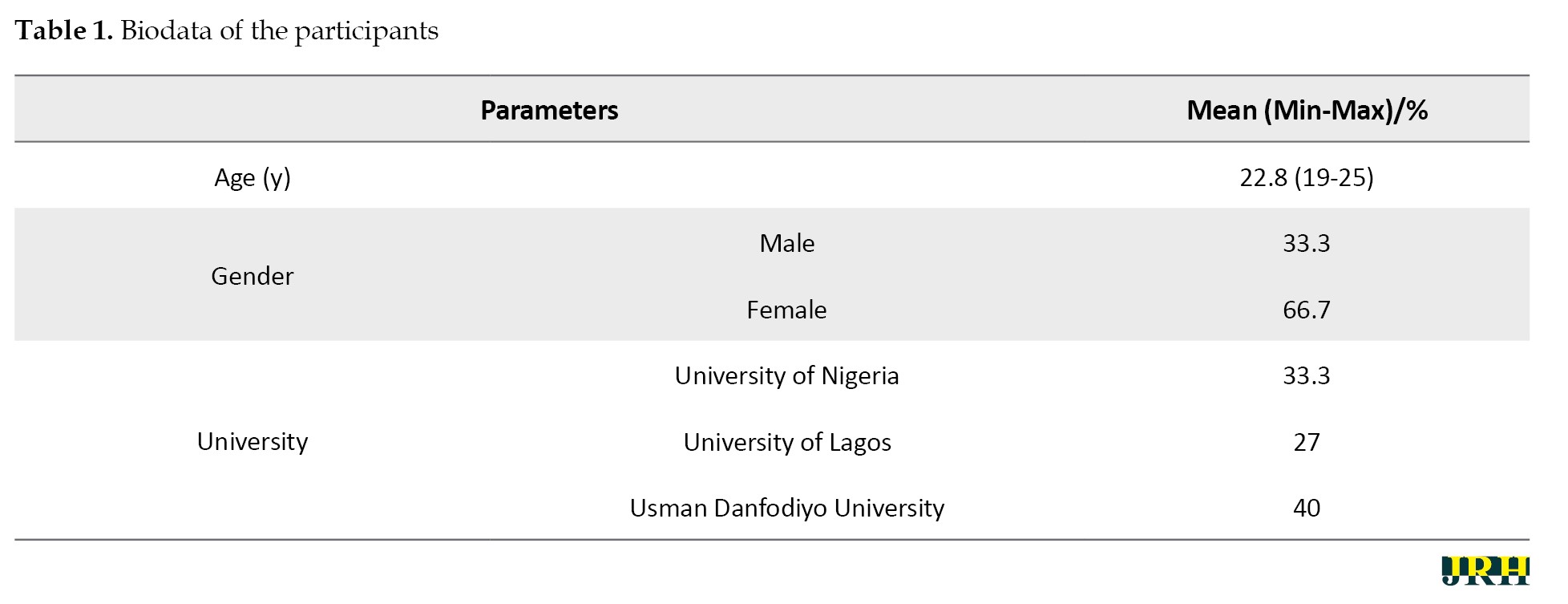

The study involved participants aged 19-25 years, with a mean age of 22.8 years (Table 1).

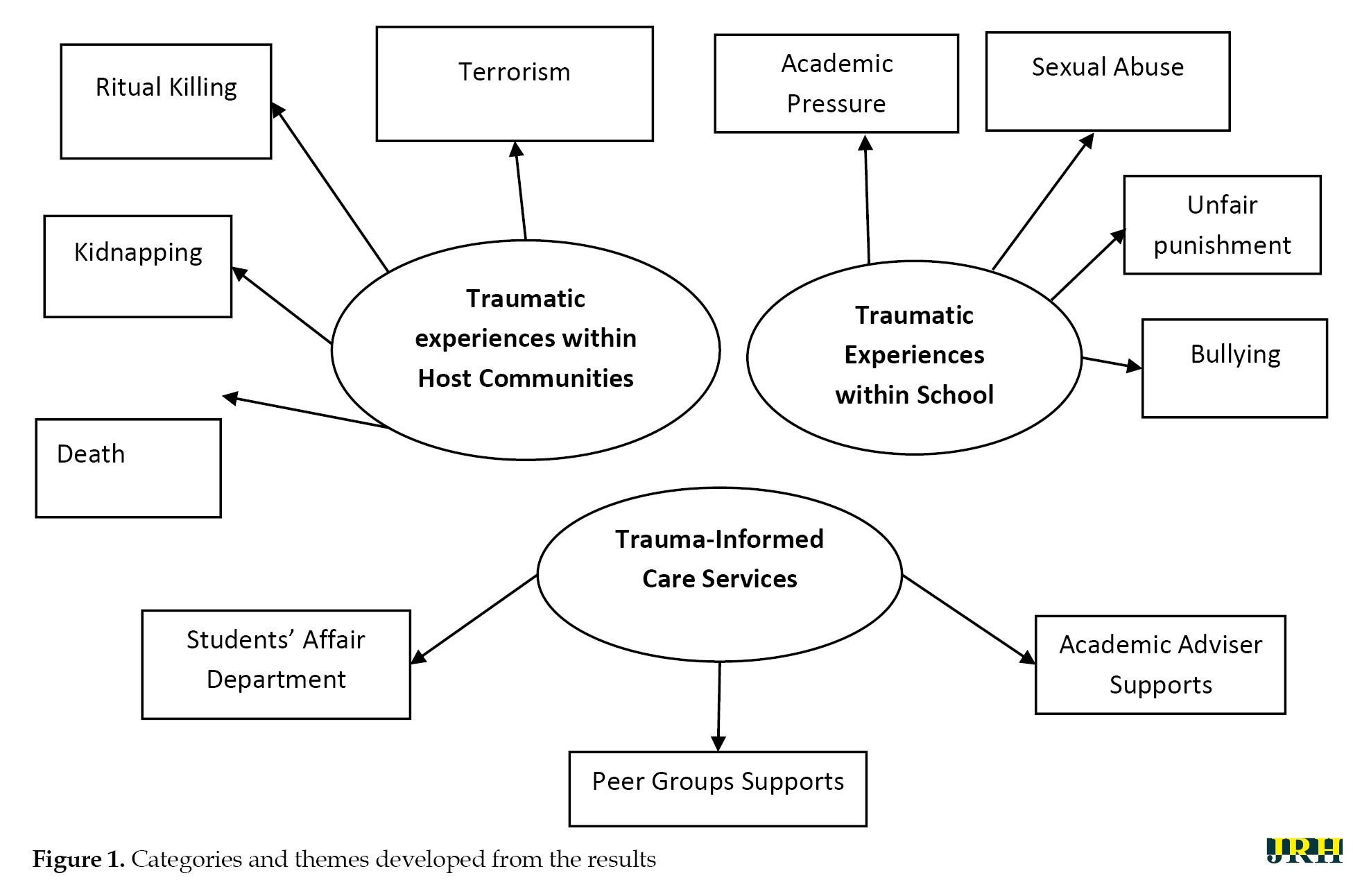

The participants were selected from various universities, including 33.3% from the University of Nigeria, 27% from the University of Lagos, and 40% from Usman Danfodiyo University. Through thematic analysis, three categories and ten themes emerged regarding students’ traumatic experiences and their access to TIC services. In Figure 1, the category of traumatic experiences within schools encompasses four themes, which include academic pressure, sexual abuse, unfair punishment, and bullying. The second category pertains to traumatic experiences within school communities, which include terrorism, kidnappings, ritual killings, and deaths. The final category is access to TIC services, made up of three themes, which include the Students’ Affairs Department, peer group support, and academic adviser support.

Traumatic experiences within schools

Undergraduate students in Nigeria face traumatic experiences, such as academic pressure, sexual abuse, unfair treatment, and bullying. This pressure is a significant source of trauma, as students feel compelled to excel due to previous failures and parental or teacher encouragement. Almost 80% of participants experienced pressure during exams. Participants’ responses:

“A lecturer reported that 70% of students failed the last session, putting academic pressure on the students and causing anxiety about the upcoming exams” [Participant (P) 8].

“Some semesters have many courses and have carryover from previous sessions. I was pressured because classes and exams may overlap [P10]”.

“…, I have considered committing suicide a good number of times due to the carryover that I had, which messed my grade, although not anymore [P1].”

Nigerian higher education experiences widespread sexual abuse, particularly among female students, leading to significant trauma and shame, with 73% reporting sexual assaults during learning activities.

“…I went to study in my friend’s room. When we went to bed, he turned off the light, and when he thought I was asleep, he spent a great deal of time caressing and suckling my breast. I was too frightened to move [P6].”

“…I have a friend that I slept over at his house countless times; it seems like he was drunk. I can’t go into details on how he raped me, but yes, I was beaten and raped by a boy that I thought was in love with me [P9].’

Nigerian universities often suffer from unfair punishment due to administrative neglect in lecturer oversight. These lecturers use minor student misbehaviours to punish the entire class, negatively impacting academic performance, student disengagement, and loss of interest in education, with 90% recounting instances of unfair punishment.

“Our lecturer gave us 20-minute breaks after teaching for an hour. I seized the opportunity to practice in class for the upcoming teaching practice. He came suddenly and accused me of imitating him, and he threatened to fail me in that course, which I later failed [P2].”

“In a microeconomics class, the lecturer ended the session after one student answered a call, advising us to study the remaining chapters for the exam [P4].”

Furthermore, undergraduate students in Nigeria experienced bullying, which affects their academic outcomes, and 33.3% of the participants emphasized this.

“…some of my classmates made fun of me each time I was unable to answer questions correctly. I felt really bad, and this messed up my self-esteem [P3].”

..Yes, final-year students usually send everyone out of class during night classes. At first, I used to get upset, but after a while, I got used to it [P5].”

“A classmate fondly called me “blacky” due to my darker skin tone, despite my requests for him to refrain from doing so. This made me depressed sometimes [P9].”

Students’ traumatic experiences within host communities

This study revealed that Nigerian students encounter traumatic events in higher education, such as terrorism, ritual killings, kidnapping, and death. All students from northern Nigeria reported attacks by Islamist gunmen on universities.

“…Yes, terrorists attacked our school. I remember being in a class that evening when it started. …., the sounds of the gunshots were what scared me the most, and each time I hear loud sounds, it reminds me of that day [P3]”.

“One day, I was on my way to school when terrorists obstructed the road. Our driver noticed them from a distance and reversed the vehicle. I was traumatised for days [P6].”

“…..Our school was locked down for three months due to terrorist activities within the host community [P6].”

Furthermore, kidnapping is a traumatic experience, affecting students’ mental health and their families. Forty-seven percent of participants reported being kidnapped, causing severe trauma and flashbacks that hindered focus on lessons.

“..my experiences with kidnappers were painful. I’m just happy to be back in one piece, but I wish I could delete the images of the body parts I saw while in captivity [P9].”

“On my way to school, the bus I was on was hijacked, and we were taken to the bush. The day I was freed, I was blindfolded and left where they had picked us up [P4]”.

“In 2022, my mum was kidnapped in Nsukka, and we were asked to bring a ransom of 1 million naira. I could not concentrate on school or anything [P8].

Ritual killing is common among students in higher education in Nigeria, impacting their mental health. This study found that 27% of the participants experienced trauma due to ritual killing in their community.

“I was going to a 7 am lecture, and I saw the corpse of a young lady. Some parts of her body were cut off. I was devastated for months [P2].”

“…I was going for exercise in the morning, and I saw some young boys with the dead body of a baby in the boot of a Mercedes-Benz. I was terrified for days [P6].”

Finally, the participants recalled that death was one of the devastating traumatic events that affected their mental health. Twenty percent of the participants identified that the deaths of their relatives and colleagues were extremely overwhelming. Here are some of the responses:

“…When my mum died, the world came crumbling down for me, and nobody understood, especially my lecturers, who did not even know about it. Her death made me so withdrawn, and it affected my grades too [P12]”.

“…a tragic motor vehicle accident on the Onitsha-Enugu expressway claimed the life of one of our classmates. The news left me in a state of shock for several days [P8]”.

Students’ access to TIC services in higher institutions

Nigerian higher education institutions offer TIC services to create a safe environment for students and support those with trauma. Participants reported access to these services from the student affairs department, peer group support, and academic adviser support, with all seeking these services. This study revealed that 50% of the participants have sought TIC from the students’ affairs department.

“…the student affairs department frustrates most students when it comes to catering for accommodation [P1 and 2]”.

“From what I heard, they have little to nothing to offer, so why waste my time [P6].”

“The students’ affairs department is filled with lackadaisical workers, and their workers at will stress you [P15].”

Academic advisers and counsellors are important for helping students deal with trauma in Nigerian universities. They act as counsellors, offering support for mental health issues. Half of the participants reported that they received TIC from their academic advisers.

“When I had a missing result, I contacted my academic adviser for help. He assisted, and my result was released [P13]”.

“One time, I was going through depression because the school activities were overwhelming, one of the ladies at guidance and counselling lent me her rant and I felt better [P3]”.

Peer and religious groups provide TIC to students, with 75% consulting them after encountering traumatic events, emphasizing the significant influence of their peers, church, and fellowship groups in post-traumatic experiences.

“I confided in my pastor about my worries regarding this course, and he directed me to a senior colleague who supported me [P2].”

“When I shared my ordeal with the church group, they were very supportive, praying for me [P10]”.

“My peer group was supportive when I told them about the number of carryovers I had. Some of them started class tutorials for me and recommended other experts in the field [P1].”

Discussion

The study examined the experiences of Nigerian students who have experienced traumatic events in school, including academic pressure, sexual harassment, bullying, and unfair disciplinary actions. These experiences negatively impact their academic performance, as students often view challenging courses as challenging due to their previous performance. Excessive stress in Nigerian academic settings is often a result of parental, peer, school, cultural, and societal pressures, which can either motivate students or lead to negative feelings and resentment towards lecturers. This aligns with findings that parental academic pressure positively correlates with students’ depression and anxiety [24] and contrasts with a study conducted on Chinese students, which found that parental pressure contributed to better academic performance [25]. The study differs from the previous study, as parental pressure in Nigeria is a source of stress, while in Australia, it is a source of motivation [25]. These differences can be attributed to cultural influences, as Nigeria is a collectivist culture where students are reminded that their academic achievements contribute to their community's welfare. Nigerian students face socio-economic disparities in their academic success compared to Australian students, who value an individualistic culture and focus on personal ambitions. Nigeria faces challenges, like corruption and deteriorating infrastructure, while Australia has a developed, high-income, and resilient digital economy.

Additionally, this study highlights the traumatic experiences of students in Nigerian schools, where they often seek help from peers or lecturers. Many students are victims of rape by their peers, and Nigerian society stigmatizes victims, leading to perpetrators often not being brought to book. Survivors struggle to articulate their experiences in fear of being stigmatized. This finding resonates with the reports of Klein and Martin [26], who reported that students who experienced sexual abuse often faced mental health consequences and were less likely to file official reports. Boumpa et al.'s study [27] also found a positive correlation between child sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Furthermore, the study revealed that students in Nigerian higher education often face bullying from peers and senior colleagues, leading to emotional harm and potential mental health issues. Bullying is prevalent among final-year students who frequently bully first-year students, leading to resentment and a higher likelihood of replicating such experiences. This study aligns with Ahmed et al.'s report [28], reporting that verbal bullying is the most common bullying experience in higher education, particularly in areas not supervised by administration. It also supports Al-Darmaki et al.'s findings [29] that traditional bullying experiences, including face-to-face, verbal, and physical bullying, persist among university students. Additionally, unfair punishment in Nigerian educational institutions is common due to the administrators' inability to control lecturers' excessive behaviour. Unfair punishment can harm students’ mental well-being and academic performance, as lecturers often use insignificant offences as opportunities to punish the entire class. This finding conforms with Morrison and Bracy's reports [30, 31], indicating that students perceive school rules as unfair due to inconsistent and varied application, and teachers' responses to misbehaviour as inequitable, with consequences often escalated without sufficient rationale

Similarly, the findings showed that students in university communities face trauma events, including terrorism, mass shootings, abductions, ritualistic murders, and family deaths. This has disrupted education, leading many students to relocate to the South. The ongoing traumatic events negatively impact students' mental health. This finding aligns with that of Asante [32], who found that sociocultural elements influenced the perception of women and girls as valuable assets, leading extremist groups to view them as tools for negotiation and economic gain.

Similarly, in Southern Nigeria, students report traumatic experiences linked to ritualistic killings, possibly due to internet fraud among university students who engage in criminal activities for income. Wariboko and Nwanyanwu's study [33] highlights the deep-rooted internet fraud in Nigeria, which has intensified the get-rich-quick mentality, disrupted operations, and has serious socio-ethical implications for the country's future. These activities have affected students' social activities, with some viewing them as illegal and causing negative spiritual effects. Many associates of these fraudsters experience mental health issues. A study emphasized that internet fraudsters' murders create spillover effects, intensifying mental health issues [34]. Students in Nigeria have experienced traumatic experiences with the loss of loved ones in university, particularly in the case of mothers and accidents. These sudden deaths can lead to trauma, depression, and negatively impact mental health and learning outcomes. This aligns with prior research, which revealed that bereaved students are often dissatisfied with the support available to them, highlighting the need for increased awareness and support to help these students cope with the loss of loved ones [35].

The study revealed that students often avoid seeking TIC services from the Student Affairs Department due to perceived inefficiencies and a lack of adequate trauma care services. They also expressed distrust in available resources and concerns about confidentiality and safety. This highlights a significant gap in the department's integration of TIC, which is crucial for supporting undergraduate students' mental well-being and potentially increasing their vulnerability to PTSD. This was reported in a study, which found that financial constraints, lack of social support, difficult campus environment, and pre-existing mental health issues increase undergraduates' vulnerability to mental health disorders. Additionally, holistic strategies involving professionals from social work, psychiatry, and the arts are needed to improve understanding and access to mental health services [36]. As TIC spreads in education, educators and mental health professionals must incorporate this concept into their daily routines [37].

Practical implications of the findings

This study highlights the negative impact of traumatic events on students' outcomes, suggesting that educational institutions should provide ongoing training for faculty and staff in TIC practices to enhance mental health and promote inclusive education for traumatised students, aligning with SDG 4. Furthermore, school administrations should allocate more financial resources for infrastructure enhancement for training academic and non-academic personnel in TIC services. Since students encounter terrorist attacks in school communities, enhancing security services for the campus and surrounding areas can reduce the prevalence of terrorist activities and social violence. In addition, the Student Affairs Department should enhance TIC by training social workers, counsellors, and academic advisers to effectively deliver services, promote security architecture, and reduce traumatic school experiences.

Conclusion

The study explored the experiences of undergraduate students in Nigerian universities who have experienced trauma, including sexual abuse, bullying, academic pressure, and unfair treatment. Traumatic events, like terrorism, ritual killing, kidnapping, and death, negatively impact their mental health, engagement, and learning outcomes. Despite seeking support from the Students' Affairs Department, peers, and academic advisers, some participants expressed dissatisfaction with the services provided by the Department of Students' Affairs. The insights gained from this research can guide the development of school policies and educational programs that foster inclusive education and lifelong learning opportunities for all students with trauma, in alignment with SDG 4. The study demonstrated that the traumatic experiences of undergraduate students hinder the attainment of inclusive and equitable education for everyone. Implementing TIC services within Nigerian higher education institutions can significantly enhance access to lifelong learning opportunities for all students.

Strengths and Limitations

This study explored the lived traumatic experiences of students in Nigerian universities using an adequate sample size of 15 students selected across the country. This research has made a notable impact on the promotion of inclusive and equitable education and lifelong learning opportunities for all, aligning with the SDG 4. The findings should be applied cautiously due to the small sample size, which limits their applicability across different regions. The study excluded participants without access to virtual platforms, resulting in a reduction of valuable lived experiences.

Recommendations for future studies

The research suggests a larger sample size and a longitudinal approach to track the progression of students' traumatic experiences over time, while also highlighting the challenges faced by undergraduate Nigerian university students in accessing TIC services.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Faculty of Education Ethical Committee at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria (Code: Edu 2025/00345). All participants provided consent. Participants were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any consequences.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his gratitude to the undergraduate students who dedicated their time to this study. Additionally, he extend his sincere thanks to the independent researchers who contributed by coding the participants’ responses.

References

Trauma is a psychological condition resulting from individual experiences of atrocities, abuse, death, disasters, and casualties [1, 2]. Traumatic experiences refer to situations where social, technological, or natural influences significantly impact a student's emotional and physical well-being, leading to disruptions in their social, academic, and mental health [3]. Students’ traumatic experiences entail exposure to emotionally life-threatening situations, such as school shootings, abuse, and kidnapping [3]. Trauma occurs when a student struggles to recognise a safe space within their school environment to process and cope with distressing experiences [4, 5]. These kinds of trauma are common in educational settings and negatively impact their well-being [6]. In Nigeria, students experience traumatic events due to high levels of insecurity, which have grievously disrupted their educational system [7]. Traumatic events have created a state of uncertainty, leading to widespread deaths of students, closure of schools, and devastating impacts on the victims' educational goals [3, 7]. Northern Nigeria is experiencing a surge in terrorist attacks on universities and colleges due to armed conflict between Nigerian security forces and Boko Haram, resulting in deaths and internal displacement [8]. Also, attacks in Kaduna state have resulted in the abduction of 280 students and teachers from two schools [7] and 70 students from Yawuri Government Secondary School in Zamfara [9].

Similarly, in Southern Nigeria, insecurity due to freedom agitators (indigenous people of Biafra (IPOB)) has caused traumatic events due to their clashes with security [10]. In 2021, suspected IPOB members allegedly pursued students from Nkume secondary school during their West African Examination Council (WAEC) exams [9]. Undergraduate students' exposure to traumatic events can negatively impact cognitive skills [11], leading to behavioural issues, like aggression and emotional imbalance, potentially causing suspension [12]. Students who experience emotional stress, threats to life and property, may suffer from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the absence of trauma-informed care (TIC) [5].

TIC emerged in response to the negative effects of trauma on students, especially those with adverse childhood experiences [13]. Trauma-informed school environments help students feel supported and improve their academic success [14]. TIC implementation necessitates school leaders' support, trauma-sensitive teaching methods, positive behaviour responses, policy modifications, teacher training, and collaboration with mental health professionals [15]. Having a trauma-informed environment benefits academic performance [16], but it remains underutilized in higher education [17].

Literature abounds with students’ traumatic experiences. In studies involving traumatized students, approximately 6-12% report symptoms relevant to diagnosing PTSD, while a good number of students [85%] have been through a traumatic event during their stay in school, and 21% of the students have experienced an event during college [18]. The study differs from the current study because it was conducted in the USA and utilized a mixed-methods approach to promote trauma recovery and assist teachers in engaging trauma-affected children. Furthermore, a study reported that students who have suffered trauma will not be capable of dealing effectively with pressures, setbacks, challenges, and adversities in the future [11]. The reviewed study evaluates children's health, behaviour, and academic outcomes, unlike the current study, which explored the experiences of higher education students. A study revealed that 20% of trauma-affected youth exhibit behavioural issues, compared to only 10% without a trauma history [19]. Research shows that individuals with a history of traumatic experiences, including adverse childhood experiences, experience lifelong physical, mental, and emotional effects, potentially leading to complex mental health disorders like PTSD [20].

Concerning TIC, a study reported that trauma-informed awareness increases in knowledge of TIC and trauma-informed educational strategies and the improved ability to support students [21]. The study was not conducted in Nigeria and did not examine the students' experiences of TIC in higher education. A study outlined the rationale for trauma-informed approaches in higher education institutions, emphasising the importance of cultural competency and cultural humility through a literature review approach [22]. However, this study did not explore the lived experiences of higher education students’ access to TIC. Similarly, another study used a literature review lens to explore the incorporation of TIC into school-based programs and reported that some schools have successfully incorporated trauma-informed approaches into adolescent pregnancy prevention programs [12]. The current study focused on the experiences of traumatised students and their access to TIC at Nigerian universities, differing from the review study's objectives.

Research indicates that students frequently experience trauma in primary and secondary schools, but there is limited research on this issue in higher education in Nigeria. The study sought to provide first-hand qualitative evidence on the traumatic experiences students encounter and their access to TIC in Nigerian higher education. It aimed to answer questions about the types of academic and community-based traumatic experiences undergraduate students encounter, as well as whether they have access to TIC. The findings are expected to benefit the academic community and contribute to sustainable development goal 4 (SDG 4), which promotes quality education for all [23]. The results will help school administrators adopt effective support programs for traumatized students.

Methods

Setting and design

The study used a phenomenological qualitative research design to investigate students’ lived and shared academic and community-based traumatic experiences and their access to TIC services. Data were collected between September and November 2024 through interviews. Nigerian universities sampled included the University of Nigeria Nsukka, the University of Lagos, and Usman Danfodiyo University in Sokoto. The University of Nigeria and Lagos have histories of traumatic events, such as sexual abuses and suicidal ideations, while Usman Danfodiyo is located in a terrorist prone zone. Access to the study area was free, as responses were obtained via Zoom and Google Meet.

Participants

The study involved 15 participants recruited through departmental WhatsApp groups, with purposive sampling restricted to students in their penultimate and final years who had experienced traumatic experiences. Participants were invited to the first stage via WhatsApp. In the second stage, participants who shared weeks of traumatic experiences were selected. The third stage involved selecting internet-accessible participants for meetings via Zoom and Google Meet. The aim was to provide an overview of the research and ensure confidentiality, using pseudonyms for anonymity. Finally, 15 participants consented to participate.

Procedures

Two facilitators, Amos Nnaemeka Amedu and Veronica Dwarika, conducted semi-structured interviews through online sessions via Zoom and Google Meet. They hold PhDs in educational psychology and have extensive research expertise in qualitative approaches. The researcher developed an interview guide to promote uniformity and minimise biases. The guide covered primary research questions, open-ended questions, prompts, and follow-up questions. The facilitators underwent a day of training on the interview guide. The interviews were scheduled at participants’ convenience, and there were no right or wrong answers. The questions aim to uncover participants’ lived experiences of trauma and their access to trauma care services. Open-ended questions were used, such as Have you ever encountered any traumatic events? Can you articulate your feelings during that event? Have you ever utilised TIC services? And follow-up questions. The interviews were recorded, with each session lasting between 15 and 25 minutes. Participants’ responses were securely stored on an online platform with a password and pseudonym, providing a user-friendly interface and straightforward data storage, making it an ideal choice for researchers.

Data analysis

The recorded sessions were transcribed verbatim. Two experienced coders, who also facilitated the sessions, carried out the open coding of the transcripts. The researcher met with the coders multiple times to ensure the coding was consistent. After this phase, the researcher reviewed the coding and created initial codebooks, which were combined into a final codebook for axial coding. Frequent meetings between the researcher and coders helped reach a consensus. The coding agreement was measured using Cohen’s kappa, resulting in an 84% agreement rate. A third independent researcher performed axial coding to minimise bias. Thematic analysis was conducted by coders and an independent researcher, who categorized the codes into broader themes. The researcher defined themes, verified transcripts and codes for accuracy, and the lead independent researcher validated them before finalising them.

Results

The study involved participants aged 19-25 years, with a mean age of 22.8 years (Table 1).

The participants were selected from various universities, including 33.3% from the University of Nigeria, 27% from the University of Lagos, and 40% from Usman Danfodiyo University. Through thematic analysis, three categories and ten themes emerged regarding students’ traumatic experiences and their access to TIC services. In Figure 1, the category of traumatic experiences within schools encompasses four themes, which include academic pressure, sexual abuse, unfair punishment, and bullying. The second category pertains to traumatic experiences within school communities, which include terrorism, kidnappings, ritual killings, and deaths. The final category is access to TIC services, made up of three themes, which include the Students’ Affairs Department, peer group support, and academic adviser support.

Traumatic experiences within schools

Undergraduate students in Nigeria face traumatic experiences, such as academic pressure, sexual abuse, unfair treatment, and bullying. This pressure is a significant source of trauma, as students feel compelled to excel due to previous failures and parental or teacher encouragement. Almost 80% of participants experienced pressure during exams. Participants’ responses:

“A lecturer reported that 70% of students failed the last session, putting academic pressure on the students and causing anxiety about the upcoming exams” [Participant (P) 8].

“Some semesters have many courses and have carryover from previous sessions. I was pressured because classes and exams may overlap [P10]”.

“…, I have considered committing suicide a good number of times due to the carryover that I had, which messed my grade, although not anymore [P1].”

Nigerian higher education experiences widespread sexual abuse, particularly among female students, leading to significant trauma and shame, with 73% reporting sexual assaults during learning activities.

“…I went to study in my friend’s room. When we went to bed, he turned off the light, and when he thought I was asleep, he spent a great deal of time caressing and suckling my breast. I was too frightened to move [P6].”

“…I have a friend that I slept over at his house countless times; it seems like he was drunk. I can’t go into details on how he raped me, but yes, I was beaten and raped by a boy that I thought was in love with me [P9].’

Nigerian universities often suffer from unfair punishment due to administrative neglect in lecturer oversight. These lecturers use minor student misbehaviours to punish the entire class, negatively impacting academic performance, student disengagement, and loss of interest in education, with 90% recounting instances of unfair punishment.

“Our lecturer gave us 20-minute breaks after teaching for an hour. I seized the opportunity to practice in class for the upcoming teaching practice. He came suddenly and accused me of imitating him, and he threatened to fail me in that course, which I later failed [P2].”

“In a microeconomics class, the lecturer ended the session after one student answered a call, advising us to study the remaining chapters for the exam [P4].”

Furthermore, undergraduate students in Nigeria experienced bullying, which affects their academic outcomes, and 33.3% of the participants emphasized this.

“…some of my classmates made fun of me each time I was unable to answer questions correctly. I felt really bad, and this messed up my self-esteem [P3].”

..Yes, final-year students usually send everyone out of class during night classes. At first, I used to get upset, but after a while, I got used to it [P5].”

“A classmate fondly called me “blacky” due to my darker skin tone, despite my requests for him to refrain from doing so. This made me depressed sometimes [P9].”

Students’ traumatic experiences within host communities

This study revealed that Nigerian students encounter traumatic events in higher education, such as terrorism, ritual killings, kidnapping, and death. All students from northern Nigeria reported attacks by Islamist gunmen on universities.

“…Yes, terrorists attacked our school. I remember being in a class that evening when it started. …., the sounds of the gunshots were what scared me the most, and each time I hear loud sounds, it reminds me of that day [P3]”.

“One day, I was on my way to school when terrorists obstructed the road. Our driver noticed them from a distance and reversed the vehicle. I was traumatised for days [P6].”

“…..Our school was locked down for three months due to terrorist activities within the host community [P6].”

Furthermore, kidnapping is a traumatic experience, affecting students’ mental health and their families. Forty-seven percent of participants reported being kidnapped, causing severe trauma and flashbacks that hindered focus on lessons.

“..my experiences with kidnappers were painful. I’m just happy to be back in one piece, but I wish I could delete the images of the body parts I saw while in captivity [P9].”

“On my way to school, the bus I was on was hijacked, and we were taken to the bush. The day I was freed, I was blindfolded and left where they had picked us up [P4]”.

“In 2022, my mum was kidnapped in Nsukka, and we were asked to bring a ransom of 1 million naira. I could not concentrate on school or anything [P8].

Ritual killing is common among students in higher education in Nigeria, impacting their mental health. This study found that 27% of the participants experienced trauma due to ritual killing in their community.

“I was going to a 7 am lecture, and I saw the corpse of a young lady. Some parts of her body were cut off. I was devastated for months [P2].”

“…I was going for exercise in the morning, and I saw some young boys with the dead body of a baby in the boot of a Mercedes-Benz. I was terrified for days [P6].”

Finally, the participants recalled that death was one of the devastating traumatic events that affected their mental health. Twenty percent of the participants identified that the deaths of their relatives and colleagues were extremely overwhelming. Here are some of the responses:

“…When my mum died, the world came crumbling down for me, and nobody understood, especially my lecturers, who did not even know about it. Her death made me so withdrawn, and it affected my grades too [P12]”.

“…a tragic motor vehicle accident on the Onitsha-Enugu expressway claimed the life of one of our classmates. The news left me in a state of shock for several days [P8]”.

Students’ access to TIC services in higher institutions

Nigerian higher education institutions offer TIC services to create a safe environment for students and support those with trauma. Participants reported access to these services from the student affairs department, peer group support, and academic adviser support, with all seeking these services. This study revealed that 50% of the participants have sought TIC from the students’ affairs department.

“…the student affairs department frustrates most students when it comes to catering for accommodation [P1 and 2]”.

“From what I heard, they have little to nothing to offer, so why waste my time [P6].”

“The students’ affairs department is filled with lackadaisical workers, and their workers at will stress you [P15].”

Academic advisers and counsellors are important for helping students deal with trauma in Nigerian universities. They act as counsellors, offering support for mental health issues. Half of the participants reported that they received TIC from their academic advisers.

“When I had a missing result, I contacted my academic adviser for help. He assisted, and my result was released [P13]”.

“One time, I was going through depression because the school activities were overwhelming, one of the ladies at guidance and counselling lent me her rant and I felt better [P3]”.

Peer and religious groups provide TIC to students, with 75% consulting them after encountering traumatic events, emphasizing the significant influence of their peers, church, and fellowship groups in post-traumatic experiences.

“I confided in my pastor about my worries regarding this course, and he directed me to a senior colleague who supported me [P2].”

“When I shared my ordeal with the church group, they were very supportive, praying for me [P10]”.

“My peer group was supportive when I told them about the number of carryovers I had. Some of them started class tutorials for me and recommended other experts in the field [P1].”

Discussion

The study examined the experiences of Nigerian students who have experienced traumatic events in school, including academic pressure, sexual harassment, bullying, and unfair disciplinary actions. These experiences negatively impact their academic performance, as students often view challenging courses as challenging due to their previous performance. Excessive stress in Nigerian academic settings is often a result of parental, peer, school, cultural, and societal pressures, which can either motivate students or lead to negative feelings and resentment towards lecturers. This aligns with findings that parental academic pressure positively correlates with students’ depression and anxiety [24] and contrasts with a study conducted on Chinese students, which found that parental pressure contributed to better academic performance [25]. The study differs from the previous study, as parental pressure in Nigeria is a source of stress, while in Australia, it is a source of motivation [25]. These differences can be attributed to cultural influences, as Nigeria is a collectivist culture where students are reminded that their academic achievements contribute to their community's welfare. Nigerian students face socio-economic disparities in their academic success compared to Australian students, who value an individualistic culture and focus on personal ambitions. Nigeria faces challenges, like corruption and deteriorating infrastructure, while Australia has a developed, high-income, and resilient digital economy.

Additionally, this study highlights the traumatic experiences of students in Nigerian schools, where they often seek help from peers or lecturers. Many students are victims of rape by their peers, and Nigerian society stigmatizes victims, leading to perpetrators often not being brought to book. Survivors struggle to articulate their experiences in fear of being stigmatized. This finding resonates with the reports of Klein and Martin [26], who reported that students who experienced sexual abuse often faced mental health consequences and were less likely to file official reports. Boumpa et al.'s study [27] also found a positive correlation between child sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Furthermore, the study revealed that students in Nigerian higher education often face bullying from peers and senior colleagues, leading to emotional harm and potential mental health issues. Bullying is prevalent among final-year students who frequently bully first-year students, leading to resentment and a higher likelihood of replicating such experiences. This study aligns with Ahmed et al.'s report [28], reporting that verbal bullying is the most common bullying experience in higher education, particularly in areas not supervised by administration. It also supports Al-Darmaki et al.'s findings [29] that traditional bullying experiences, including face-to-face, verbal, and physical bullying, persist among university students. Additionally, unfair punishment in Nigerian educational institutions is common due to the administrators' inability to control lecturers' excessive behaviour. Unfair punishment can harm students’ mental well-being and academic performance, as lecturers often use insignificant offences as opportunities to punish the entire class. This finding conforms with Morrison and Bracy's reports [30, 31], indicating that students perceive school rules as unfair due to inconsistent and varied application, and teachers' responses to misbehaviour as inequitable, with consequences often escalated without sufficient rationale

Similarly, the findings showed that students in university communities face trauma events, including terrorism, mass shootings, abductions, ritualistic murders, and family deaths. This has disrupted education, leading many students to relocate to the South. The ongoing traumatic events negatively impact students' mental health. This finding aligns with that of Asante [32], who found that sociocultural elements influenced the perception of women and girls as valuable assets, leading extremist groups to view them as tools for negotiation and economic gain.

Similarly, in Southern Nigeria, students report traumatic experiences linked to ritualistic killings, possibly due to internet fraud among university students who engage in criminal activities for income. Wariboko and Nwanyanwu's study [33] highlights the deep-rooted internet fraud in Nigeria, which has intensified the get-rich-quick mentality, disrupted operations, and has serious socio-ethical implications for the country's future. These activities have affected students' social activities, with some viewing them as illegal and causing negative spiritual effects. Many associates of these fraudsters experience mental health issues. A study emphasized that internet fraudsters' murders create spillover effects, intensifying mental health issues [34]. Students in Nigeria have experienced traumatic experiences with the loss of loved ones in university, particularly in the case of mothers and accidents. These sudden deaths can lead to trauma, depression, and negatively impact mental health and learning outcomes. This aligns with prior research, which revealed that bereaved students are often dissatisfied with the support available to them, highlighting the need for increased awareness and support to help these students cope with the loss of loved ones [35].

The study revealed that students often avoid seeking TIC services from the Student Affairs Department due to perceived inefficiencies and a lack of adequate trauma care services. They also expressed distrust in available resources and concerns about confidentiality and safety. This highlights a significant gap in the department's integration of TIC, which is crucial for supporting undergraduate students' mental well-being and potentially increasing their vulnerability to PTSD. This was reported in a study, which found that financial constraints, lack of social support, difficult campus environment, and pre-existing mental health issues increase undergraduates' vulnerability to mental health disorders. Additionally, holistic strategies involving professionals from social work, psychiatry, and the arts are needed to improve understanding and access to mental health services [36]. As TIC spreads in education, educators and mental health professionals must incorporate this concept into their daily routines [37].

Practical implications of the findings

This study highlights the negative impact of traumatic events on students' outcomes, suggesting that educational institutions should provide ongoing training for faculty and staff in TIC practices to enhance mental health and promote inclusive education for traumatised students, aligning with SDG 4. Furthermore, school administrations should allocate more financial resources for infrastructure enhancement for training academic and non-academic personnel in TIC services. Since students encounter terrorist attacks in school communities, enhancing security services for the campus and surrounding areas can reduce the prevalence of terrorist activities and social violence. In addition, the Student Affairs Department should enhance TIC by training social workers, counsellors, and academic advisers to effectively deliver services, promote security architecture, and reduce traumatic school experiences.

Conclusion

The study explored the experiences of undergraduate students in Nigerian universities who have experienced trauma, including sexual abuse, bullying, academic pressure, and unfair treatment. Traumatic events, like terrorism, ritual killing, kidnapping, and death, negatively impact their mental health, engagement, and learning outcomes. Despite seeking support from the Students' Affairs Department, peers, and academic advisers, some participants expressed dissatisfaction with the services provided by the Department of Students' Affairs. The insights gained from this research can guide the development of school policies and educational programs that foster inclusive education and lifelong learning opportunities for all students with trauma, in alignment with SDG 4. The study demonstrated that the traumatic experiences of undergraduate students hinder the attainment of inclusive and equitable education for everyone. Implementing TIC services within Nigerian higher education institutions can significantly enhance access to lifelong learning opportunities for all students.

Strengths and Limitations

This study explored the lived traumatic experiences of students in Nigerian universities using an adequate sample size of 15 students selected across the country. This research has made a notable impact on the promotion of inclusive and equitable education and lifelong learning opportunities for all, aligning with the SDG 4. The findings should be applied cautiously due to the small sample size, which limits their applicability across different regions. The study excluded participants without access to virtual platforms, resulting in a reduction of valuable lived experiences.

Recommendations for future studies

The research suggests a larger sample size and a longitudinal approach to track the progression of students' traumatic experiences over time, while also highlighting the challenges faced by undergraduate Nigerian university students in accessing TIC services.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Faculty of Education Ethical Committee at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria (Code: Edu 2025/00345). All participants provided consent. Participants were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any consequences.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his gratitude to the undergraduate students who dedicated their time to this study. Additionally, he extend his sincere thanks to the independent researchers who contributed by coding the participants’ responses.

References

- Mathur M, Mehta GC, Rawat VS. Victims of war and terrorism. In: Gopalan RT, editor. Victimology. Cham: Springer; 2022. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-12930-8_8]

- Amedu AN, Dwarika V. Enhancing the mental health of children, students, and adolescents with trauma and PTSD through TF-CBT. Archives of Trauma Research. 2024; 13(1):1-11. [DOI:10.48307/atr.2024.422501.1045]

- Amedu AN, Dwarika V, Aigbodion VV. Addressing students’ traumatic experiences and impact of social supports: Scoping review. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2025; 9(1):100512. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejtd.2025.100512]

- Bremner D. You Can’t Just Snap Out of It: The real path to recovery from psychological trauma. Chicago: Laughing Cow Books; 2014. [Link]

- Hoffman W A. The incidence of traumatic events and trauma-associated symptoms/experiences amongst tertiary students. South African Journal of Psychology. 2002; 32(4):48-53.[Link]

- Huang LN, Flatow R, Biggs T, Afayee S, Smith K, Clark T, et al. SAMHSA’s Concept of truama and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Maryland: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); 2014. [Link]

- Paul M. Educational insecurity in northwest Nigeria. International Journal of Religion. 2024;1-14. [Link]

- Ibrahim UU, Abubakar Aliyu A, Abdulhakeem OA, Abdulaziz M, Asiya M, Sabitu K, et al. Prevalence of Boko Haram crisis related depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology among internally displaced persons in Yobe state, North East, Nigeria. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2023; 13:100590. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100590]

- Igboeli CC, Nnamdi O, Obi IE, Okafor O, Obikeze NA. School insecurity and students academic engagement in nigeria public university. COOU Journal of Educational Research. 2021; 6(2):19-24. [Link]

- Akeem Idowu S. Between Self-determination and Secession: An assessment of the indigenous people of Biafra (IPOB) agitations for the independence of southeast Nigeria [MA thesis]. Tromsø: The Arctic University of Norway; 2023. [Link]

- Theisen CM. A Literature review supporting trauma-informed decision making in schools [MA thesis]. Minnesota: Bethel University; 2020. [Link]

- Martin SL, Ashley OS, White L, Axelson S, Clark M, Burrus B. Incorporating trauma-informed care into school-based programs. Journal of School Health. 2017; 87(12):958-67. [DOI:10.1111/josh.12568] [PMID]

- Cannon LM, Coolidge EM, LeGierse J, Moskowitz Y, Buckley C, Chapin E, et al. Trauma-informed education: Creating and pilot testing a nursing curriculum on trauma-informed care. Nurse Education Today. 2020; 85:104256. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104256] [PMID]

- Broadbent-Hogan P. How do you create a trauma-informed classroom that promotes regulation and learning? Qualitative Research Journal. 2024. [DOI:10.1108/QRJ-06-2024-0126]

- Oehlberg B. Why schools need to be trauma informed. Trauma and Loss: Research and Interventions. 2008; 8(2):1-4. [Link]

- Maynard BR, Farina A, Dell NA, Kelly MS. Effects of trauma‐informed approaches in schools: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2019; 15(1-2):e1018. [DOI:10.1002/cl2.1018] [PMID]

- Rissanen A. Mental health supports for post-secondary students: What students need and what institutions provide. Seattle: City University of Seattle; 2024; [Link]

- Frazier P, Anders S, Perera S, Tomich P, Tennen H, Park C, et al. Traumatic events among undergraduate students: Prevalence and associated symptoms. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009; 56(3):450-60. [DOI:10.1037/a0016412]

- Fondren K, Lawson M, Speidel R, McDonnell CG, Valentino K. Buffering the effects of childhood trauma within the school setting: A systematic review of trauma-informed and trauma-responsive interventions among trauma-affected youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;109:104691. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104691]

- Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the Lifespan. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018; 9:420. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420] [PMID]

- Doughty K. Increasing trauma-informed awareness and practice in higher education. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2020; 40(1):66-8. [DOI:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000279] [PMID]

- Henshaw LA. Building Trauma-Informed Approaches in Higher Education. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(10):368. [DOI:10.3390/bs12100368] [PMID]

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS. New York: United Nations; 2024. [Link]

- Quach AS, Epstein NB, Riley PJ, Falconier MK, Fang X. Effects of Parental Warmth and Academic Pressure on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Chinese Adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015; 24(1):106-16. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-013-9818-y]

- Deb S, Strodl E, Sun H. Academic stress, parental pressure, anxiety and mental health among Indian high school students. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science. 2015; 5(1):26-34. [Link]

- Klein LB, Martin SL. Sexual harassment of college and university students: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2021; 22(4):777-92. [DOI:10.1177/1524838019881731] [PMID]

- Boumpa V, Papatoukaki A, Kourti A, Mintzia S, Panagouli E, Bacopoulou F, et al. Sexual abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2024; 33(6):1653-73. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-022-02015-5] [PMID]

- Ahmed B, Yousaf FN, Ahmad A, Zohra T, Ullah W. Bullying in educational institutions: college students’ experiences. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2023; 28(9):2713-9. [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2022.2067338] [PMID]

- Al-Darmaki F, Al Sabbah H, Haroun D. Prevalence of bullying behaviors among students from a National University in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022; 13:768305. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.768305] [PMID]

- Morrison K. Students’ Perceptions of Unfair Discipline in School. The Journal of Classroom Interaction. 2018; 53(2):21-45. [Link]

- Bracy NL. Student perceptions of high-security school environments. Youth & Society. 2011; 43(1):365-95. [DOI:10.1177/0044118X10365082]

- Asante P. School abductions in Chibok and Zamfara, Nigeria : The nexus between gender, terror and official response [MA thesis]. As: Norwegian University of Life Sciences ;2021.[Link]

- Wariboko OPC, Nwanyanwu FC. The dark side of connectivity: A socio-ethical exploration of internet fraud and Nigerian youth. Àgídìgbo: ABUAD Journal of the Humanities. 2024; 12(1):89-104. [DOI:10.53982/agidigbo.2024.1201.06-j]

- Nwobodo RE. A critical examination of ‘Yahoo-Yahoo’ among Nigerian Youths as a breach of African culture and values. International Journal of Religious and Cultural Practice. 2024; 9(2):1-17. [Link]

- Balk DE. Death, bereavement and college students: A descriptive analysis. Mortality. 1997; 2(3):207-20. [DOI:10.1080/713685866]

- Ikpeama C, Onalu C, Idu A. Knowledge, and access to mental health services for undergraduates in university of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. Social Work in Mental Health. 2025; 23(2):1-18. [DOI:10.1080/15332985.2025.2449957]

- Reinbergs EJ, Fefer SA. Addressing trauma in schools: Multitiered service delivery options for practitioners. Psychology in the schools. 2018; 55(3):250-63. [DOI:10.1002/pits.22105]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2025/02/17 | Accepted: 2025/05/19 | Published: 2025/11/1

Received: 2025/02/17 | Accepted: 2025/05/19 | Published: 2025/11/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |