Volume 15, Issue 6 (Nov & Dec 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(6): 549-558 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: NU/COMHS/EBC0021/2022

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Simon M A, Ranganath R, Ibrahim AlAbduwani F, AlJahafi A, AlKindy K A, Shah Y A et al . Leveraging Online Pathways for Health Promotion: Effects of a Peer-led Psychosocial Intervention Module on Breast Cancer Awareness and Breast Self-examination. J Research Health 2025; 15 (6) :549-558

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2779-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2779-en.html

Miriam Archana Simon1

, Rajani Ranganath2

, Rajani Ranganath2

, Fatma Ibrahim AlAbduwani3

, Fatma Ibrahim AlAbduwani3

, Aafaq Salim AlJahafi3

, Aafaq Salim AlJahafi3

, Khulood Adil AlKindy3

, Khulood Adil AlKindy3

, Yusra Abid Shah3

, Yusra Abid Shah3

, John C. Muthusami4

, John C. Muthusami4

, Rajani Ranganath2

, Rajani Ranganath2

, Fatma Ibrahim AlAbduwani3

, Fatma Ibrahim AlAbduwani3

, Aafaq Salim AlJahafi3

, Aafaq Salim AlJahafi3

, Khulood Adil AlKindy3

, Khulood Adil AlKindy3

, Yusra Abid Shah3

, Yusra Abid Shah3

, John C. Muthusami4

, John C. Muthusami4

1- Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman. , miriamsimon@nu.edu.om

2- Department of Pathology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman.

3- College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman.

4- Department of Surgery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman.

2- Department of Pathology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman.

3- College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman.

4- Department of Surgery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman.

Full-Text [PDF 785 kb]

(221 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2242 Views)

Full-Text: (317 Views)

Introduction

Breast cancer is reported to be the most common cancer among women and results in approximately 15% of cancer deaths worldwide [1]. Early detection and treatment of breast cancer play a crucial role in increasing survival rates [2]. Breast self-examination is a low-risk, low-cost method for early detection of cancer, which is vital for improved mortality, and women are encouraged to regularly engage in this practice [3]. Research has indicated that awareness of breast cancer may significantly impact help-seeking behaviors in women. In addition, studies also indicate that a lack of knowledge may result in delayed presentation and thus may affect treatment [4]. Research has highlighted the importance of practicing breast self-examination as an important component of personal health advocacy [5]. Studies have also indicated the importance of addressing the associated psychosocial factors related to breast cancer [6], as the primary obstacles to early detection commonly include misconceptions and social stigma [7]. Health education and health activism techniques that focus on secondary prevention of breast cancer often involve awareness programs and training in breast self-exams [5].

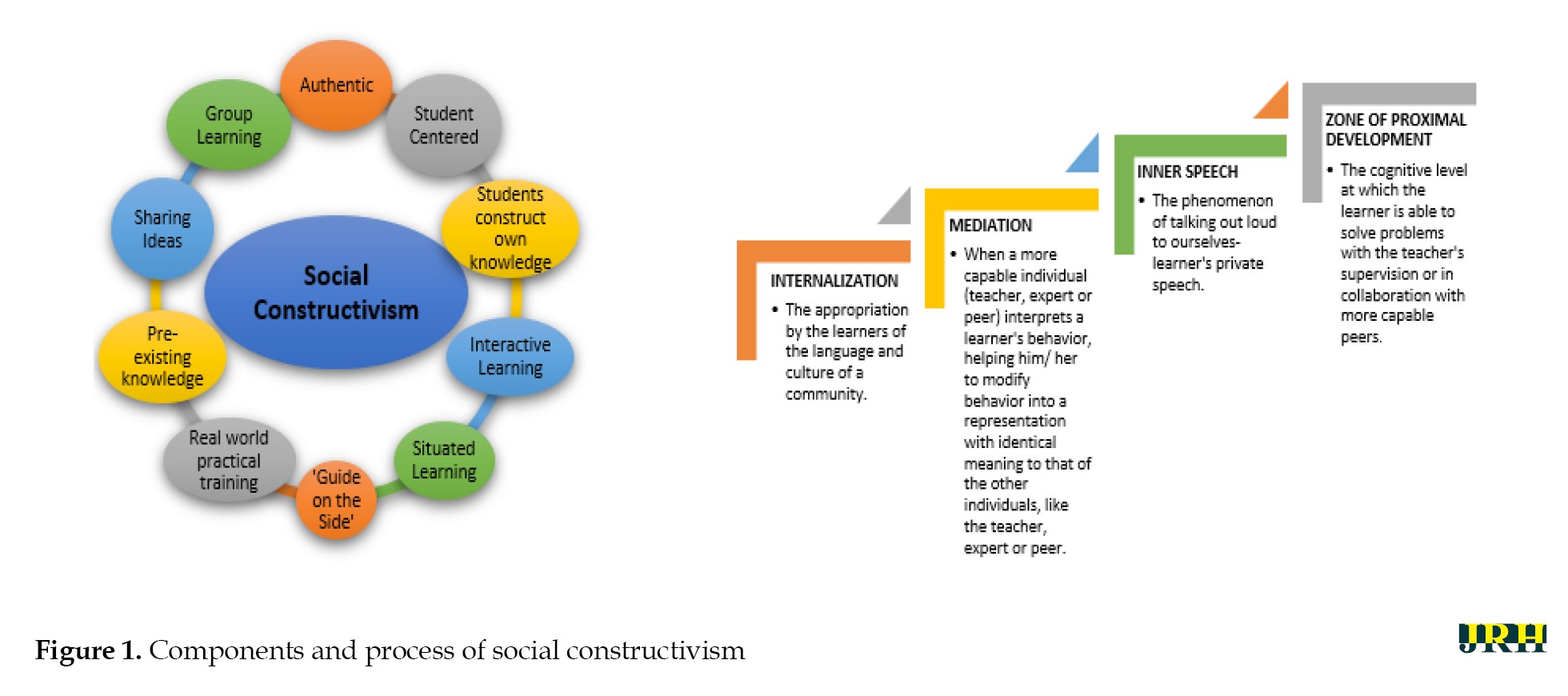

Multiple modalities of interventions to promote health and well-being are frequently utilized by educators and trainers. However, meta-analyses of impact studies indicate that a planned and systematic application of social science theory in interventional programs has a high level of effectiveness [8]. The popular learning theory of constructivism stipulates that learners construct knowledge by experience rather than just passively absorbing information [9] and that critical reflection is a vital component of the learning process [10]. One of the types of constructivism is social constructivism, which prioritizes the collaborative nature of learning [11]. This theory, put forth by Lev Vygotsky in 1968, states that learning occurs by means of interaction within a cultural setting. Social constructivism views knowledge as what learners do in collaboration with others- teachers and/or peers [12]. The various components and learning process of the community of inquiry postulated by this theory are portrayed in Figure 1 [13, 14]. Being perceptive to learning as a social process and providing opportunities for learning in a social context is gaining ground in medical education [10]. Research indicates that social constructivism in medical education is commonly applied during instruction involving social and cultural behaviors, social constructs, and learners’ identity transformation [15]. Peer-assisted learning is a teaching-learning method that is founded on the principles of social constructivism [16]. This method involves the development of new knowledge and skills through active learning support received from peer tutors. An additional benefit to this process is that peer tutors themselves are learning through teaching [17].

Globally, health promotion and health awareness programs in online mode are increasing, especially following the COVID-19 pandemic. Research has indicated the efficacy of such online interventional sessions [18, 19]. In addition, the advantages of online health promotion programs include being able to reach a larger proportion of participants/audience and utilizing a lower extent of resources [20]. Theories of online learning state that one of the most effective designs of online content delivery would be through a community-centered lens. This is based on Vygotsky’s concept of social constructivism and social cognition. In this scenario, students would work together in an online learning context to create new knowledge [21].

Medical students have vital future roles in health advocacy, and it is imperative that this competency be nurtured. Closely tied to the concept of social accountability, student involvement in health advocacy during medical school increases accountability to ensure an equitable healthcare system and address health disparities [22]. Although medical students acknowledge the need for health advocacy in society, research indicates that they feel unprepared to address these needs [23]. Providing a platform based on a validated theoretical framework enhances the effectiveness of health advocacy roles and planned interventional modules. Digital peer-assisted learning modalities are frequently used in health professions education [24], but there is a lack of evidence related to health awareness and health advocacy. In addition, there is minimal evidence regarding online peer-assisted learning programs that incorporate a psychosocial interventional module for breast cancer awareness. Most online interventions focus on breast cancer survivors [25] with limited digital modules implemented for preventive healthcare addressing related psychosocial dimensions.

The aim of the present study was to assess the effectiveness of an online peer-led psychosocial interventional module for breast cancer awareness and breast self-examination that was designed on the social constructivism framework. The integration of psychosocial aspects for breast cancer awareness within a validated framework of social constructivism and the utilization of peer-led online delivery modality by medical students to enhance health advocacy and preventive healthcare are the highlights of the current study.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study was cross-sectional using the quasi-experimental intervention method conducted in March 2021. Participants included medical students from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman. To ensure gender and cultural sensitivity, female students were invited to attend a peer-led online workshop on breast cancer awareness and breast self-examination. All female students enrolled at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman, were invited to participate. Male students were excluded from the study. Convenience sampling was employed. Registration for the workshop was carried out using Google Forms. The online platform used for workshop delivery was WebEx. Approval for the study was obtained from the institution’s Ethics and Biosafety Committee. Data were collected from 93 students who registered for the workshop. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Confidentiality in data handling was ensured.

Procedure

The training-learning paradigm for this study was designed according to the social constructivism framework, which inculcated the paradigm of collaborative learning. It was a session by the students (peer tutors) for the students (participants), which focused on creating a conducive online peer-led learning environment. A training workshop was initially conducted for the peer tutors by faculty mentors on various aspects of peer-assisted learning and the process of conducting a workshop. They were also trained by discipline-specific faculty members in the delivery of the workshop on topics related to breast cancer, breast self-examination, and associated psychosocial dimensions. Multiple rehearsals were conducted to ensure the validity of the content and the efficacy of the presentation during the workshop.

The psychosocial aspects focused on during the online workshop included addressing myths related to breast cancer, the psychological and social impact of breast cancer, dealing with stigma, psychosocial strategies for therapy and intervention, quality of life (QoL) issues, and associated challenges faced by physicians. The training modalities utilized during the workshop included mini-lectures, online game-based activities, case-based discussions, narrative techniques, and live demonstrations. Participant engagement was ensured through online game-based checkpoints, as well as time allotted for questions and discussions.

Participants were required to complete a pre-validated questionnaire by Ranganath et al. (2020) [26] on psychosocial aspects related to breast cancer and breast self-examination, both prior to and at the conclusion of the workshop. The questionnaire included 14 items—11 quantitative and 3 qualitative—for which content validity was established by subject experts. This questionnaire assessed participants’ perceptions related to the psychosocial aspects of breast cancer on three levels: Individual factors, interpersonal factors, and community factors. Participants’ perceptions relating to common myths about breast cancer were also assessed. They also provided feedback regarding their experience of the peer-led workshop.

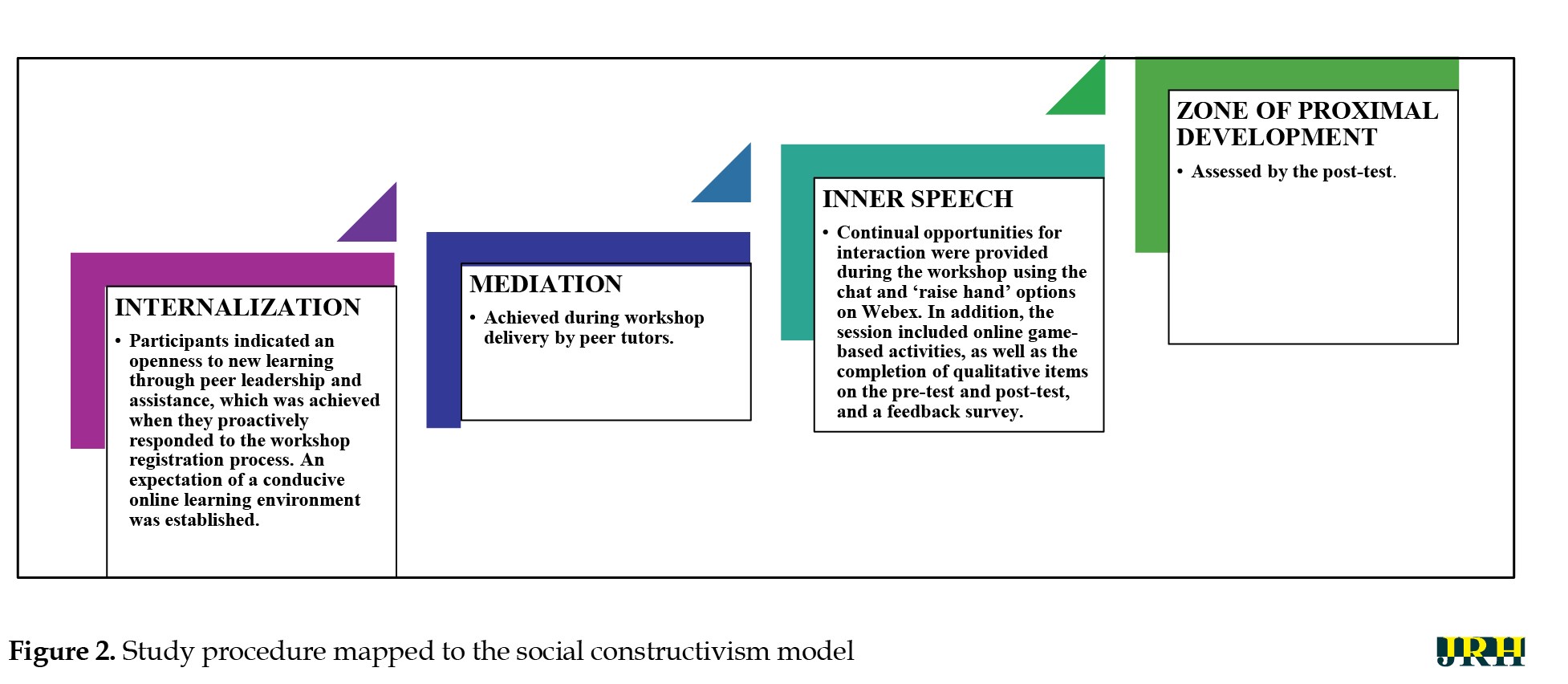

The study procedure steps mapped to the social constructivist model are shown in Figure 2.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyze participants’ responses to the pre-test and post-test questionnaires. Reliability analysis was carried out using Cronbach’s α to assess internal consistency. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were employed to interpret associations. Linear regression analysis was carried out to explore the strength of association. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyze differences between participants’ scores in the pre-test and post-test phases. Thematic analysis of qualitative items was also conducted.

Results

Ninety-three medical students across all years of study participated in the workshop. The mean age of the participants was 22 years. Cronbach’s α value, indicating internal consistency, was obtained for the 11 quantitative test items (r=0.61). This indicates adequate reliability of the survey items utilized for the study. In addition, the establishment of content validity ensures that the survey adequately aligns with the study objectives. Results of the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality for the survey items (P<0.001) indicate that participants’ responses were not normally distributed.

The results are presented according to the following sections:

Myths and facts related to breast cancer and breast self-examination

Psychosocial factors - individual level, interpersonal level, community level

Myths and facts related to breast cancer and breast self-examination

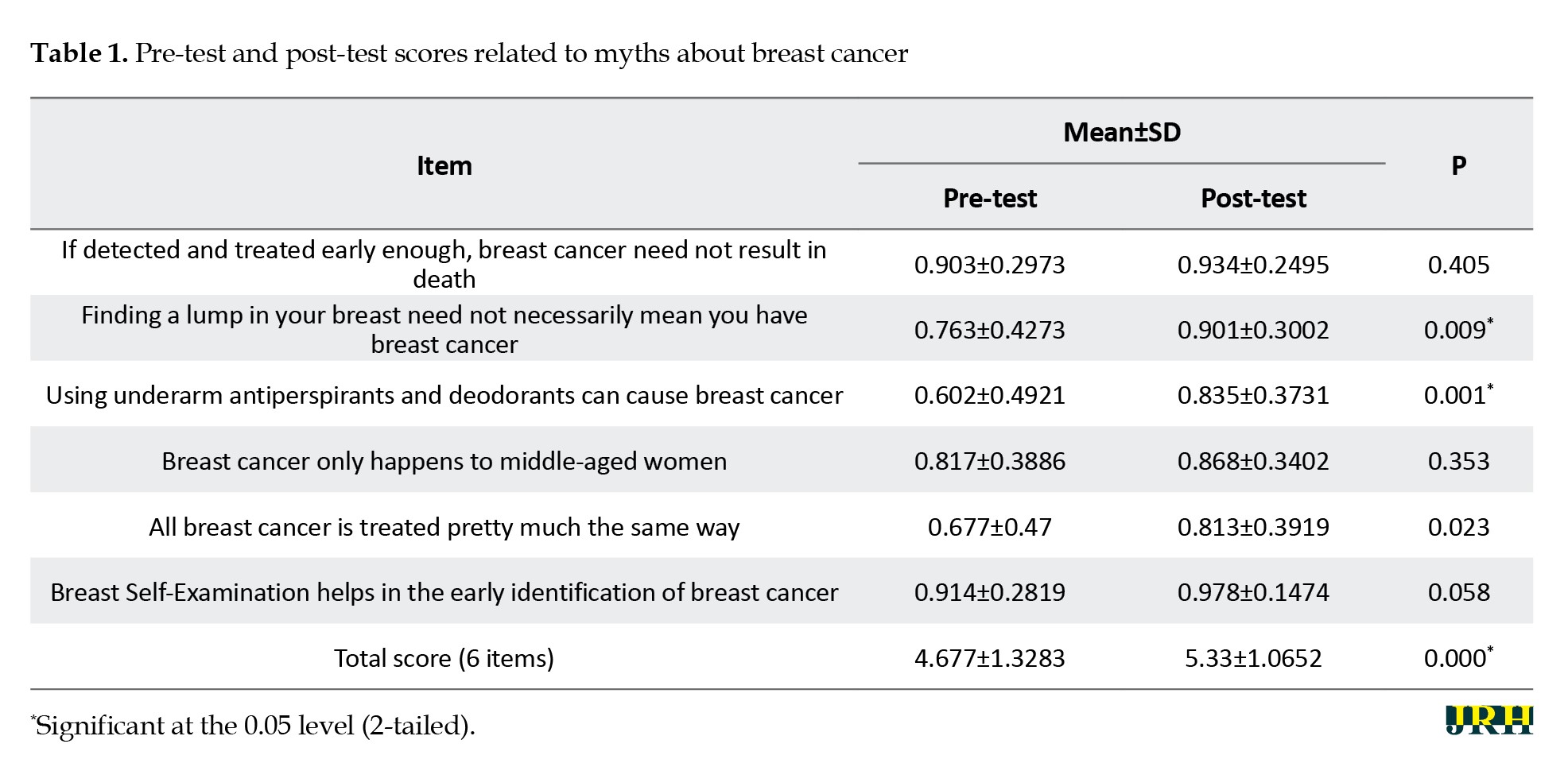

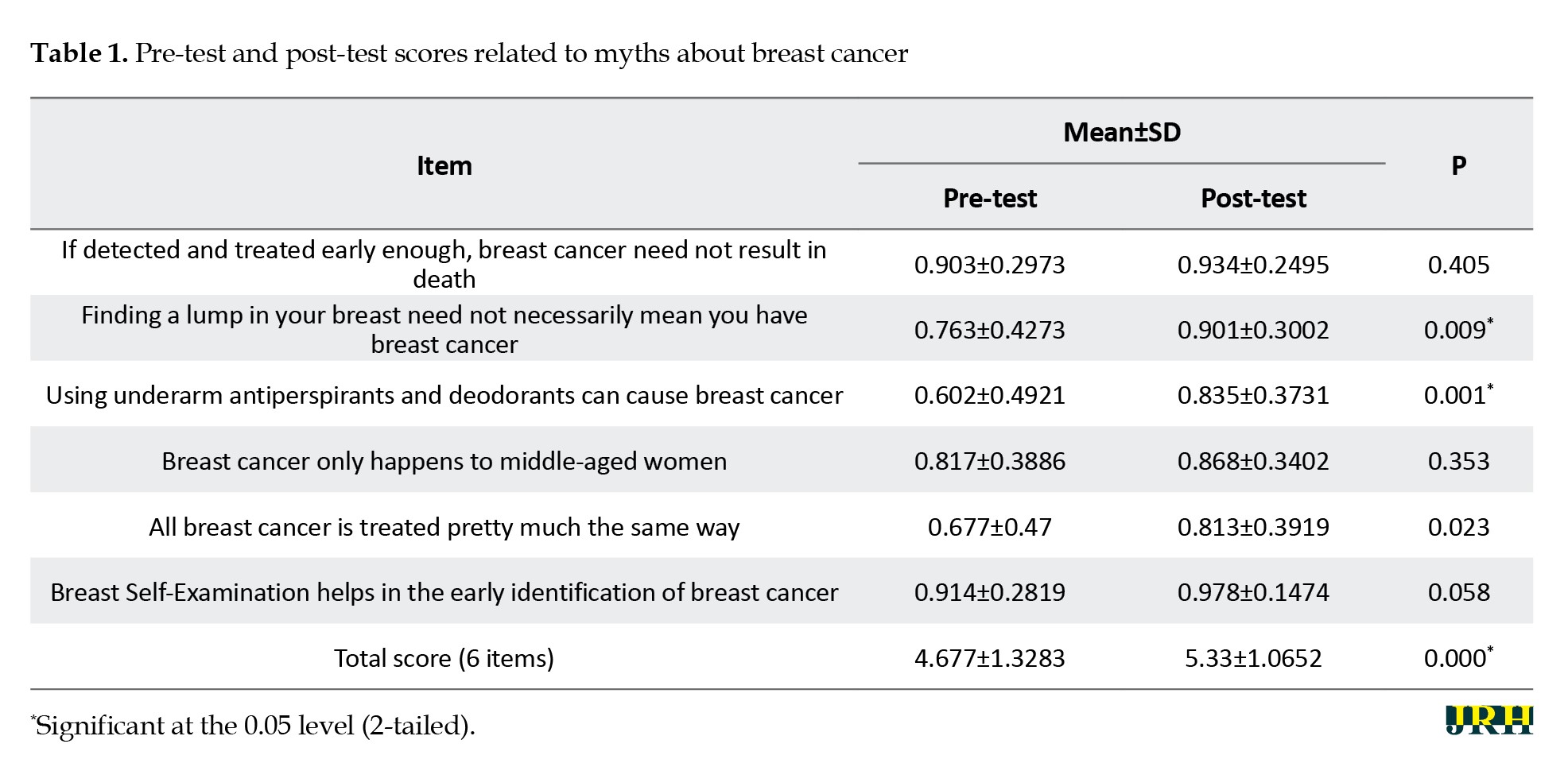

Participants were asked to differentiate between a few facts and myths about breast cancer using true or false items. Participants’ responses are shown in Table 1.

Results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated that there was a significant improvement in the overall perception of participants regarding the facts and myths about breast cancer after the workshop. In addition, pre-existing myths related to the identification of various types of breast lumps and the role of body fragrance products as a risk factor in breast cancer were also effectively rectified.

Psychosocial factors

Individual level

This section assessed the openness of participants to regularly practice breast self-examination and their perceived personal psychosocial barriers to doing so. Although overall post-test scores increased, statistical significance was not observed in this area (P=0.063).

Interpersonal level

Participants were willing to recommend and teach breast self-examination to those they were familiar with. This shows the effectiveness of the online peer-led workshop in enabling participants to proactively address various issues related to breast cancer awareness (Z=-3.094; P=0.002).

Community level

Following the online workshop, participants exhibited a high level of openness to disseminate information about breast cancer and training on breast self-examination at the community level. Post-test scores indicated a significant increase among workshop participants (P=0.043).

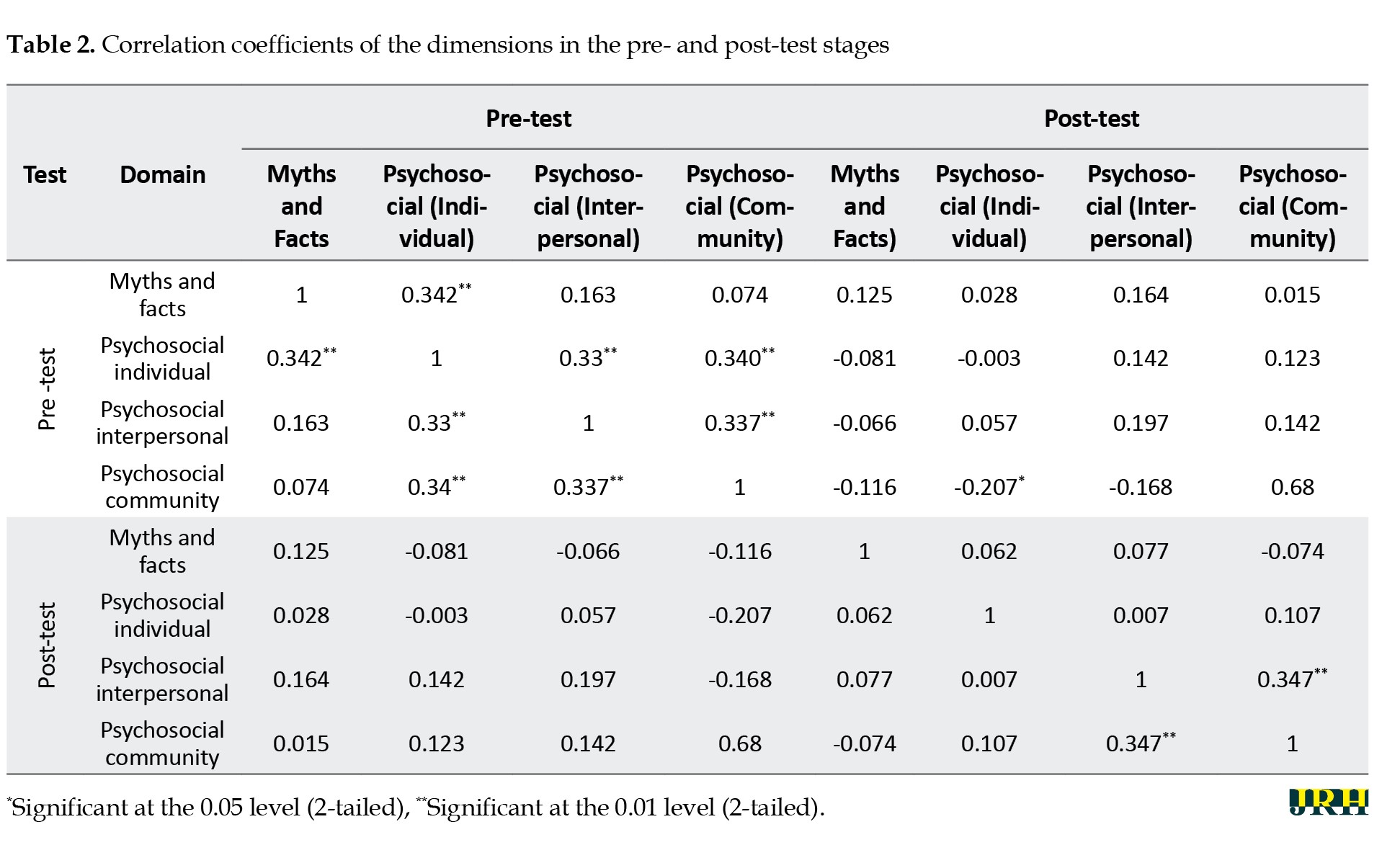

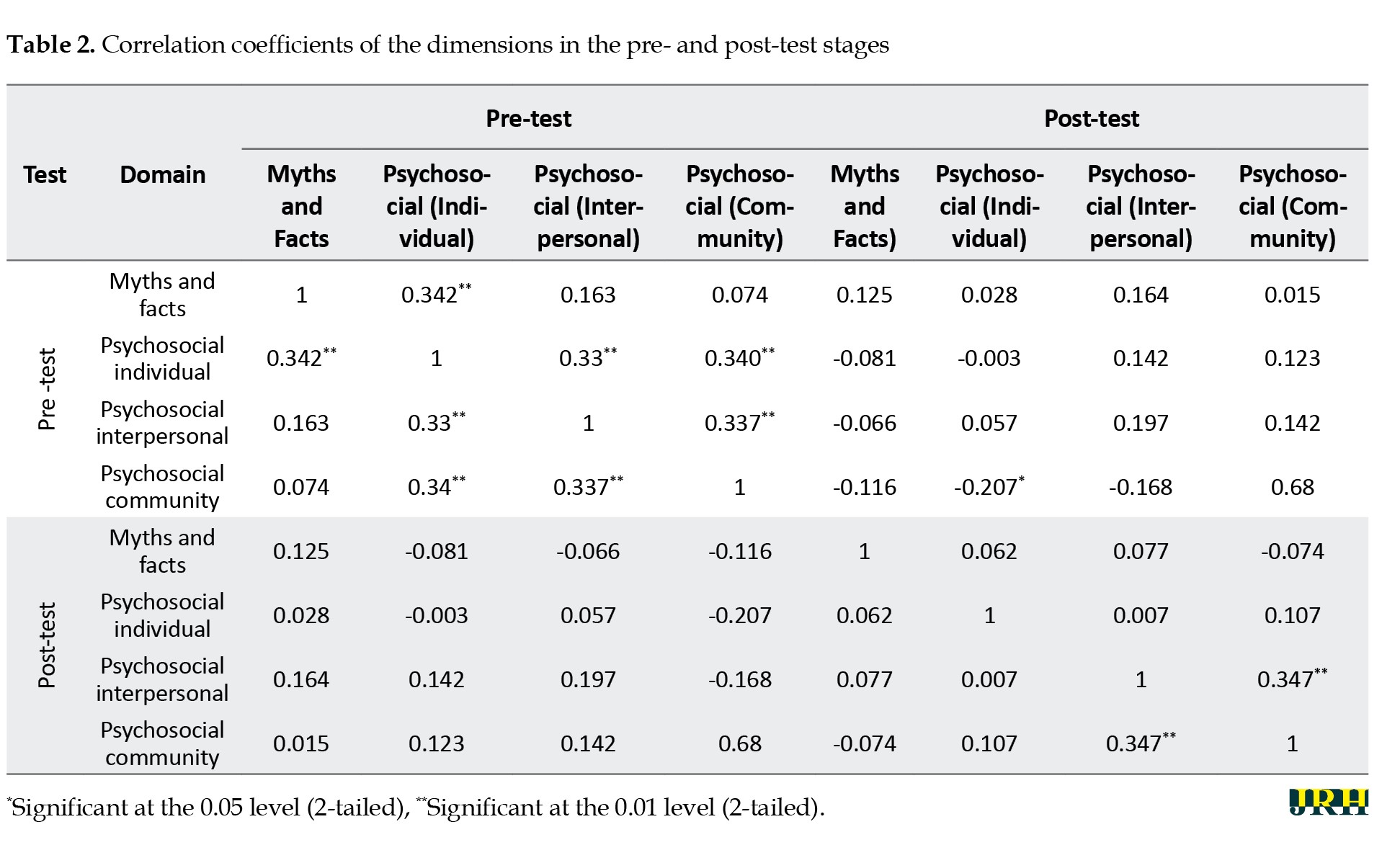

Spearman’s correlation analysis of both pre-test and post-test scores indicates significant associations among various questionnaire domains, as shown in Table 2.

Correlation analysis

Spearman’s correlation coefficients of both pre-test and post-test stages indicated significant associations among various questionnaire domains, as shown in Table 2.

The perception of myths was highly related to individual factors, with improvements observed in post-test scores. Additionally, interpersonal and community factors (e.g. social stigma) are associated with individual beliefs. Changes in post-test scores were evident in these dimensions, indicating the effectiveness of the online peer-led workshop in improving and reshaping perceptions.

Linear regression

Pre-test scores indicated that individual, interpersonal, and community factors were not strong predictors of openness and perceptions regarding breast cancer and breast self-examination. Post-test analysis indicated that interpersonal (R2=0.924) and community (R2=0.884) factors were strong predictors of participants’ perceptions. This underscores the effectiveness of the peer-led workshop and its impact on enhancing positive changes in attitudes and mindsets.

Qualitative analysis

Three open-ended items were included in the survey: (i) Women who are diagnosed with breast cancer commonly experience anxiety and depression. Mention other emotional difficulties that they may experience; (ii) Mention psychological strategies that can be used to help women cope with a diagnosis of breast cancer; (iii) Mention three social challenges that are experienced by women who are diagnosed with breast cancer.

Participants were asked to mention the emotional difficulties that women who are diagnosed with breast cancer may experience. Frequent pre-test responses included ‘fear, stress, and sadness’. Post-test responses included ‘grief, anxiety, low self-esteem, challenges with body image, and isolation’. Following the online workshop, participants reported an in-depth understanding of the complex emotional factors associated with breast cancer. Some responses included “self-isolation”, “self-blame”, “lack of self-worth”, and “feeling of being a burden to others”.

The knowledge of psychosocial interventional strategies also improved in participants after the workshop. Many pre-test responses for this theme included ‘I don’t know’. A few participants reported that using motivational talk and encouragement may be utilized to help patients. Post-test responses indicated a positive improvement in this area. Participant responses suggested that psychotherapy, psychoeducation, group and family therapy, and enhancing a supportive social environment would help patients and survivors.

Prior to the workshop, participants had minimal awareness of the social challenges faced by breast cancer patients and survivors. A few responses included ‘family problems’. Post-test responses indicated a drastic modification in participants’ perceptions. Answers included “fear of divorce”, “economic challenges”, “stigma”, “social isolation”, and “challenges in accessing healthcare services”.

Thematic analysis of qualitative items in the questionnaire using axial coding indicated the effectiveness of the online peer-led workshop across the following dimensions: (i) stimulating a change in participants’ perceptions regarding the associated psychosocial aspects of breast cancer and (ii) the importance of incorporating validated psychotherapeutic strategies for management.

Feedback survey

A majority of participants felt that the workshop was interesting (86.7%), effective (73.3%), and increased their knowledge regarding breast cancer (83.3%). Participants believed they were given adequate opportunities during the online workshop to share (83.3%), discuss, and engage (76.7%). They also reported feeling relaxed (83.3%) and enjoyed the online learning environment led by their peers (83.3%). Additionally, students indicated that they would prefer peer-led sessions to learn new health-related information (76.7%).

Overall, the effectiveness of applying the social constructivist model to online health education and health promotion is demonstrated by the results of the study. In addition, the effective role of medical students as catalysts in modifying health awareness and health education initiatives is highlighted.

Discussion

“The first step toward change is awareness,” said Nathaniel Branden [27]. Positive changes related to the area of health capital of communities critically involve successful health education programs [28] that focus on creating awareness and improving primary and secondary prevention. Traditionally, health awareness programs have most frequently been delivered in person. However, changing global trends and individual preferences have prompted health educators to design online modalities for delivering such sessions. Research has underscored the efficacy of online health awareness programs [18], and this effect is also reflected in the results of the present study.

An additional successful outcome of the current study was the pragmatic utilization of the social constructivism framework to maximize impact. Theorists describe four convergent lenses that are considered vital to the online learning framework: Being community-centered, knowledge-centered, learner-centered, and assessment-centered [21]. The study design, which was based on a peer-led approach involving active learning tasks with pre-test and post-test components, fulfilled the requirements of a productive online learning environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) elucidates effective health promotion activities to include educational, motivational, skill-building, and consciousness-raising techniques [28], all of which were adhered to in the current study design by following the social constructivism approach. This is further highlighted by the significant improvements in post-test results—both quantitative and qualitative. Therefore, it is integral to design online health awareness programs based on a proven theoretical learning framework to enhance effectiveness.

Utilizing the peer-assisted learning approach, based on positive peer influences, to health education initiatives has been strongly recommended by the WHO, especially related to mental health and social services. The WHO reiterates the importance of healthcare providers being effectively equipped with skills to support individuals’ psychosocial needs [29]. As seen in the results of the present study, training medical students as peer educators to advocate wellbeing practices will, in turn, greatly influence empowering other peers and the community [28].

Globally, there is a significant workforce shortage of professionals in healthcare [30]. This shortage can negatively affect the frequency and delivery of community-based training programs that focus on self-care, disease prevention, or early intervention. Leveraging the involvement of medical students in health education programs can open new avenues to reach larger populations and optimize training measures for health and well-being. The notion that medical schools are viewed as gatekeepers and value setters for healthcare practices enhances the roles and responsibilities of medical students toward the social mission of improving community health outcomes [31]. In addition, implementing online modes of delivery as a novel pathway to health awareness programs for the community can also be beneficial and enhance participation, especially for individuals in rural or remote areas.

Another benefit of online programs would be the potential to address sensitive topics (such as breast self-examination) without generating much reticence among participants. Previous literature has indicated the utilization of virtual modes focused on breast cancer survivors and the implementation of online support groups [25]. The current study highlights the efficacious modality of online health promotion initiatives for breast cancer awareness and breast self-examination. Such opportunities will also enable medical students to identify with and assist their local community, which they will serve as health professionals in the future. Therefore, a dual advantage exists, with both students and the community experiencing immense gains.

Research has indicated that addressing psychosocial aspects of diseases is important, especially for providing a holistic approach to treatment and management [32]. The current study focused on a psychosocial interventional module for breast cancer awareness. Results of a meta-analysis indicate that breast cancer in the Middle Eastern region is associated with strong social and psychological implications. Psychosocial challenges include a lack of knowledge about breast cancer, inhibition toward breast self-examination, fear of social stigma, embarrassment, and cultural beliefs [6]. The components of the psychosocial interventional module designed for this study were appropriate to effectively address regional and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior. The outcomes of the peer-led workshop included significant rectification of myths related to breast cancer and improvements in associated perceptions regarding inter-personal and community influences.

The workshop facilitated participants in envisioning the provision of holistic patient care, empowering self-care, and igniting the aspiration to be involved in health promotion. It is therefore vital to design health education programs to include an understanding of associated psychological and social processes to optimize the health and well-being of individuals and communities [28]. Directions for future research may involve designing the intervention for diverse community-based populations and exploring long-term behavioral outcomes.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that designing health awareness programs based on proven learning theories and approaches is effective. Utilization of the social constructivism framework involving peer-assisted learning provides optimal results for community-based health promotion initiatives. The role of medical students in peer-led health education initiatives is also effective. In addition, it is also vital to address psychosocial dimensions in training programs to ensure holistic approaches to self-awareness, health-related practices, disease prevention, treatment, and management. The study also indicates the effectiveness of peer-led online training as a successful pathway in health awareness and health education.

In conclusion, this study highlights the novel integration of psychosocial components into breast cancer awareness and the effectiveness of the application of social constructivism in an online modality. The study’s findings have the potential to influence future health education initiatives, including the incorporation of peer-led workshops into medical curricula and the expansion of online interventions for community outreach.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study included the restricted availability of literature related to previously conducted online health awareness programs based on theoretical learning frameworks. Due to the short-term nature of the online intervention, a control group could not be included as part of the study design. In addition, longitudinal follow-up with participants to investigate an indication of deep learning was not carried out.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics and Biosafety Committee at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman (Code: NU/COMHS/EBC0021/2022). Confidentiality of participant data was ensured, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Rajani Ranganath, John C. Muthusami, and Miriam Archana Simon; Methodology, validation and visualization: Rajani Ranganath, John C. Muthusami, and Miriam Archana Simon; Investigation, data curation, review, and editing: All authors; Formal analysis and writing the original draft: Miriam Archana Simon; Project administration: Rajani Ranganath; Supervision: John C. Muthusami.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship, IT Services, and Administrative Departments at the College of Medicine, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman, for the support received in conducting the online workshop. The authors also thank the study participants for their proactive engagement.

References

Breast cancer is reported to be the most common cancer among women and results in approximately 15% of cancer deaths worldwide [1]. Early detection and treatment of breast cancer play a crucial role in increasing survival rates [2]. Breast self-examination is a low-risk, low-cost method for early detection of cancer, which is vital for improved mortality, and women are encouraged to regularly engage in this practice [3]. Research has indicated that awareness of breast cancer may significantly impact help-seeking behaviors in women. In addition, studies also indicate that a lack of knowledge may result in delayed presentation and thus may affect treatment [4]. Research has highlighted the importance of practicing breast self-examination as an important component of personal health advocacy [5]. Studies have also indicated the importance of addressing the associated psychosocial factors related to breast cancer [6], as the primary obstacles to early detection commonly include misconceptions and social stigma [7]. Health education and health activism techniques that focus on secondary prevention of breast cancer often involve awareness programs and training in breast self-exams [5].

Multiple modalities of interventions to promote health and well-being are frequently utilized by educators and trainers. However, meta-analyses of impact studies indicate that a planned and systematic application of social science theory in interventional programs has a high level of effectiveness [8]. The popular learning theory of constructivism stipulates that learners construct knowledge by experience rather than just passively absorbing information [9] and that critical reflection is a vital component of the learning process [10]. One of the types of constructivism is social constructivism, which prioritizes the collaborative nature of learning [11]. This theory, put forth by Lev Vygotsky in 1968, states that learning occurs by means of interaction within a cultural setting. Social constructivism views knowledge as what learners do in collaboration with others- teachers and/or peers [12]. The various components and learning process of the community of inquiry postulated by this theory are portrayed in Figure 1 [13, 14]. Being perceptive to learning as a social process and providing opportunities for learning in a social context is gaining ground in medical education [10]. Research indicates that social constructivism in medical education is commonly applied during instruction involving social and cultural behaviors, social constructs, and learners’ identity transformation [15]. Peer-assisted learning is a teaching-learning method that is founded on the principles of social constructivism [16]. This method involves the development of new knowledge and skills through active learning support received from peer tutors. An additional benefit to this process is that peer tutors themselves are learning through teaching [17].

Globally, health promotion and health awareness programs in online mode are increasing, especially following the COVID-19 pandemic. Research has indicated the efficacy of such online interventional sessions [18, 19]. In addition, the advantages of online health promotion programs include being able to reach a larger proportion of participants/audience and utilizing a lower extent of resources [20]. Theories of online learning state that one of the most effective designs of online content delivery would be through a community-centered lens. This is based on Vygotsky’s concept of social constructivism and social cognition. In this scenario, students would work together in an online learning context to create new knowledge [21].

Medical students have vital future roles in health advocacy, and it is imperative that this competency be nurtured. Closely tied to the concept of social accountability, student involvement in health advocacy during medical school increases accountability to ensure an equitable healthcare system and address health disparities [22]. Although medical students acknowledge the need for health advocacy in society, research indicates that they feel unprepared to address these needs [23]. Providing a platform based on a validated theoretical framework enhances the effectiveness of health advocacy roles and planned interventional modules. Digital peer-assisted learning modalities are frequently used in health professions education [24], but there is a lack of evidence related to health awareness and health advocacy. In addition, there is minimal evidence regarding online peer-assisted learning programs that incorporate a psychosocial interventional module for breast cancer awareness. Most online interventions focus on breast cancer survivors [25] with limited digital modules implemented for preventive healthcare addressing related psychosocial dimensions.

The aim of the present study was to assess the effectiveness of an online peer-led psychosocial interventional module for breast cancer awareness and breast self-examination that was designed on the social constructivism framework. The integration of psychosocial aspects for breast cancer awareness within a validated framework of social constructivism and the utilization of peer-led online delivery modality by medical students to enhance health advocacy and preventive healthcare are the highlights of the current study.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study was cross-sectional using the quasi-experimental intervention method conducted in March 2021. Participants included medical students from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman. To ensure gender and cultural sensitivity, female students were invited to attend a peer-led online workshop on breast cancer awareness and breast self-examination. All female students enrolled at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman, were invited to participate. Male students were excluded from the study. Convenience sampling was employed. Registration for the workshop was carried out using Google Forms. The online platform used for workshop delivery was WebEx. Approval for the study was obtained from the institution’s Ethics and Biosafety Committee. Data were collected from 93 students who registered for the workshop. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Confidentiality in data handling was ensured.

Procedure

The training-learning paradigm for this study was designed according to the social constructivism framework, which inculcated the paradigm of collaborative learning. It was a session by the students (peer tutors) for the students (participants), which focused on creating a conducive online peer-led learning environment. A training workshop was initially conducted for the peer tutors by faculty mentors on various aspects of peer-assisted learning and the process of conducting a workshop. They were also trained by discipline-specific faculty members in the delivery of the workshop on topics related to breast cancer, breast self-examination, and associated psychosocial dimensions. Multiple rehearsals were conducted to ensure the validity of the content and the efficacy of the presentation during the workshop.

The psychosocial aspects focused on during the online workshop included addressing myths related to breast cancer, the psychological and social impact of breast cancer, dealing with stigma, psychosocial strategies for therapy and intervention, quality of life (QoL) issues, and associated challenges faced by physicians. The training modalities utilized during the workshop included mini-lectures, online game-based activities, case-based discussions, narrative techniques, and live demonstrations. Participant engagement was ensured through online game-based checkpoints, as well as time allotted for questions and discussions.

Participants were required to complete a pre-validated questionnaire by Ranganath et al. (2020) [26] on psychosocial aspects related to breast cancer and breast self-examination, both prior to and at the conclusion of the workshop. The questionnaire included 14 items—11 quantitative and 3 qualitative—for which content validity was established by subject experts. This questionnaire assessed participants’ perceptions related to the psychosocial aspects of breast cancer on three levels: Individual factors, interpersonal factors, and community factors. Participants’ perceptions relating to common myths about breast cancer were also assessed. They also provided feedback regarding their experience of the peer-led workshop.

The study procedure steps mapped to the social constructivist model are shown in Figure 2.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyze participants’ responses to the pre-test and post-test questionnaires. Reliability analysis was carried out using Cronbach’s α to assess internal consistency. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were employed to interpret associations. Linear regression analysis was carried out to explore the strength of association. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyze differences between participants’ scores in the pre-test and post-test phases. Thematic analysis of qualitative items was also conducted.

Results

Ninety-three medical students across all years of study participated in the workshop. The mean age of the participants was 22 years. Cronbach’s α value, indicating internal consistency, was obtained for the 11 quantitative test items (r=0.61). This indicates adequate reliability of the survey items utilized for the study. In addition, the establishment of content validity ensures that the survey adequately aligns with the study objectives. Results of the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality for the survey items (P<0.001) indicate that participants’ responses were not normally distributed.

The results are presented according to the following sections:

Myths and facts related to breast cancer and breast self-examination

Psychosocial factors - individual level, interpersonal level, community level

Myths and facts related to breast cancer and breast self-examination

Participants were asked to differentiate between a few facts and myths about breast cancer using true or false items. Participants’ responses are shown in Table 1.

Results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated that there was a significant improvement in the overall perception of participants regarding the facts and myths about breast cancer after the workshop. In addition, pre-existing myths related to the identification of various types of breast lumps and the role of body fragrance products as a risk factor in breast cancer were also effectively rectified.

Psychosocial factors

Individual level

This section assessed the openness of participants to regularly practice breast self-examination and their perceived personal psychosocial barriers to doing so. Although overall post-test scores increased, statistical significance was not observed in this area (P=0.063).

Interpersonal level

Participants were willing to recommend and teach breast self-examination to those they were familiar with. This shows the effectiveness of the online peer-led workshop in enabling participants to proactively address various issues related to breast cancer awareness (Z=-3.094; P=0.002).

Community level

Following the online workshop, participants exhibited a high level of openness to disseminate information about breast cancer and training on breast self-examination at the community level. Post-test scores indicated a significant increase among workshop participants (P=0.043).

Spearman’s correlation analysis of both pre-test and post-test scores indicates significant associations among various questionnaire domains, as shown in Table 2.

Correlation analysis

Spearman’s correlation coefficients of both pre-test and post-test stages indicated significant associations among various questionnaire domains, as shown in Table 2.

The perception of myths was highly related to individual factors, with improvements observed in post-test scores. Additionally, interpersonal and community factors (e.g. social stigma) are associated with individual beliefs. Changes in post-test scores were evident in these dimensions, indicating the effectiveness of the online peer-led workshop in improving and reshaping perceptions.

Linear regression

Pre-test scores indicated that individual, interpersonal, and community factors were not strong predictors of openness and perceptions regarding breast cancer and breast self-examination. Post-test analysis indicated that interpersonal (R2=0.924) and community (R2=0.884) factors were strong predictors of participants’ perceptions. This underscores the effectiveness of the peer-led workshop and its impact on enhancing positive changes in attitudes and mindsets.

Qualitative analysis

Three open-ended items were included in the survey: (i) Women who are diagnosed with breast cancer commonly experience anxiety and depression. Mention other emotional difficulties that they may experience; (ii) Mention psychological strategies that can be used to help women cope with a diagnosis of breast cancer; (iii) Mention three social challenges that are experienced by women who are diagnosed with breast cancer.

Participants were asked to mention the emotional difficulties that women who are diagnosed with breast cancer may experience. Frequent pre-test responses included ‘fear, stress, and sadness’. Post-test responses included ‘grief, anxiety, low self-esteem, challenges with body image, and isolation’. Following the online workshop, participants reported an in-depth understanding of the complex emotional factors associated with breast cancer. Some responses included “self-isolation”, “self-blame”, “lack of self-worth”, and “feeling of being a burden to others”.

The knowledge of psychosocial interventional strategies also improved in participants after the workshop. Many pre-test responses for this theme included ‘I don’t know’. A few participants reported that using motivational talk and encouragement may be utilized to help patients. Post-test responses indicated a positive improvement in this area. Participant responses suggested that psychotherapy, psychoeducation, group and family therapy, and enhancing a supportive social environment would help patients and survivors.

Prior to the workshop, participants had minimal awareness of the social challenges faced by breast cancer patients and survivors. A few responses included ‘family problems’. Post-test responses indicated a drastic modification in participants’ perceptions. Answers included “fear of divorce”, “economic challenges”, “stigma”, “social isolation”, and “challenges in accessing healthcare services”.

Thematic analysis of qualitative items in the questionnaire using axial coding indicated the effectiveness of the online peer-led workshop across the following dimensions: (i) stimulating a change in participants’ perceptions regarding the associated psychosocial aspects of breast cancer and (ii) the importance of incorporating validated psychotherapeutic strategies for management.

Feedback survey

A majority of participants felt that the workshop was interesting (86.7%), effective (73.3%), and increased their knowledge regarding breast cancer (83.3%). Participants believed they were given adequate opportunities during the online workshop to share (83.3%), discuss, and engage (76.7%). They also reported feeling relaxed (83.3%) and enjoyed the online learning environment led by their peers (83.3%). Additionally, students indicated that they would prefer peer-led sessions to learn new health-related information (76.7%).

Overall, the effectiveness of applying the social constructivist model to online health education and health promotion is demonstrated by the results of the study. In addition, the effective role of medical students as catalysts in modifying health awareness and health education initiatives is highlighted.

Discussion

“The first step toward change is awareness,” said Nathaniel Branden [27]. Positive changes related to the area of health capital of communities critically involve successful health education programs [28] that focus on creating awareness and improving primary and secondary prevention. Traditionally, health awareness programs have most frequently been delivered in person. However, changing global trends and individual preferences have prompted health educators to design online modalities for delivering such sessions. Research has underscored the efficacy of online health awareness programs [18], and this effect is also reflected in the results of the present study.

An additional successful outcome of the current study was the pragmatic utilization of the social constructivism framework to maximize impact. Theorists describe four convergent lenses that are considered vital to the online learning framework: Being community-centered, knowledge-centered, learner-centered, and assessment-centered [21]. The study design, which was based on a peer-led approach involving active learning tasks with pre-test and post-test components, fulfilled the requirements of a productive online learning environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) elucidates effective health promotion activities to include educational, motivational, skill-building, and consciousness-raising techniques [28], all of which were adhered to in the current study design by following the social constructivism approach. This is further highlighted by the significant improvements in post-test results—both quantitative and qualitative. Therefore, it is integral to design online health awareness programs based on a proven theoretical learning framework to enhance effectiveness.

Utilizing the peer-assisted learning approach, based on positive peer influences, to health education initiatives has been strongly recommended by the WHO, especially related to mental health and social services. The WHO reiterates the importance of healthcare providers being effectively equipped with skills to support individuals’ psychosocial needs [29]. As seen in the results of the present study, training medical students as peer educators to advocate wellbeing practices will, in turn, greatly influence empowering other peers and the community [28].

Globally, there is a significant workforce shortage of professionals in healthcare [30]. This shortage can negatively affect the frequency and delivery of community-based training programs that focus on self-care, disease prevention, or early intervention. Leveraging the involvement of medical students in health education programs can open new avenues to reach larger populations and optimize training measures for health and well-being. The notion that medical schools are viewed as gatekeepers and value setters for healthcare practices enhances the roles and responsibilities of medical students toward the social mission of improving community health outcomes [31]. In addition, implementing online modes of delivery as a novel pathway to health awareness programs for the community can also be beneficial and enhance participation, especially for individuals in rural or remote areas.

Another benefit of online programs would be the potential to address sensitive topics (such as breast self-examination) without generating much reticence among participants. Previous literature has indicated the utilization of virtual modes focused on breast cancer survivors and the implementation of online support groups [25]. The current study highlights the efficacious modality of online health promotion initiatives for breast cancer awareness and breast self-examination. Such opportunities will also enable medical students to identify with and assist their local community, which they will serve as health professionals in the future. Therefore, a dual advantage exists, with both students and the community experiencing immense gains.

Research has indicated that addressing psychosocial aspects of diseases is important, especially for providing a holistic approach to treatment and management [32]. The current study focused on a psychosocial interventional module for breast cancer awareness. Results of a meta-analysis indicate that breast cancer in the Middle Eastern region is associated with strong social and psychological implications. Psychosocial challenges include a lack of knowledge about breast cancer, inhibition toward breast self-examination, fear of social stigma, embarrassment, and cultural beliefs [6]. The components of the psychosocial interventional module designed for this study were appropriate to effectively address regional and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior. The outcomes of the peer-led workshop included significant rectification of myths related to breast cancer and improvements in associated perceptions regarding inter-personal and community influences.

The workshop facilitated participants in envisioning the provision of holistic patient care, empowering self-care, and igniting the aspiration to be involved in health promotion. It is therefore vital to design health education programs to include an understanding of associated psychological and social processes to optimize the health and well-being of individuals and communities [28]. Directions for future research may involve designing the intervention for diverse community-based populations and exploring long-term behavioral outcomes.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that designing health awareness programs based on proven learning theories and approaches is effective. Utilization of the social constructivism framework involving peer-assisted learning provides optimal results for community-based health promotion initiatives. The role of medical students in peer-led health education initiatives is also effective. In addition, it is also vital to address psychosocial dimensions in training programs to ensure holistic approaches to self-awareness, health-related practices, disease prevention, treatment, and management. The study also indicates the effectiveness of peer-led online training as a successful pathway in health awareness and health education.

In conclusion, this study highlights the novel integration of psychosocial components into breast cancer awareness and the effectiveness of the application of social constructivism in an online modality. The study’s findings have the potential to influence future health education initiatives, including the incorporation of peer-led workshops into medical curricula and the expansion of online interventions for community outreach.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study included the restricted availability of literature related to previously conducted online health awareness programs based on theoretical learning frameworks. Due to the short-term nature of the online intervention, a control group could not be included as part of the study design. In addition, longitudinal follow-up with participants to investigate an indication of deep learning was not carried out.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics and Biosafety Committee at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman (Code: NU/COMHS/EBC0021/2022). Confidentiality of participant data was ensured, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Rajani Ranganath, John C. Muthusami, and Miriam Archana Simon; Methodology, validation and visualization: Rajani Ranganath, John C. Muthusami, and Miriam Archana Simon; Investigation, data curation, review, and editing: All authors; Formal analysis and writing the original draft: Miriam Archana Simon; Project administration: Rajani Ranganath; Supervision: John C. Muthusami.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship, IT Services, and Administrative Departments at the College of Medicine, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman, for the support received in conducting the online workshop. The authors also thank the study participants for their proactive engagement.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018; 68(6):394-424. [DOI:10.3322/caac.21492] [PMID]

- Ginsburg O, Yip C, Brooks A, Cabanes A, Caleffi M, Dunstan Yataco JA, et al. Breast cancer early detection: A phased approach to implementation. Cancer. 2020; 126(S10):2379-93. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.32887] [PMID]

- Huang N, Chen L, He J, Nguyen QD. The efficacy of clinical breast exams and breast self-exams in detecting malignancy or positive ultrasound findings. Cureus. 2022; 14(2):e22464. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.22464]

- Ramya Ahmad S, Asmaa Ahmad A, Nesreen Abdullah A, Rana Ahmad Bin S, Shaimaa Amer A, Aisha T, et al. Awareness level, knowledge and attitude towards breast cancer between medical and non-medical university students in Makkah region: A cross sectional study. International Journal of Cancer and Clinical Research. 2019; 6:106. [DOI:10.23937/2378-3419/1410106]

- Pippin MM, Boyd R. Breast self-examination. [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Link]

- Salem H, Daher-Nashif S. Psychosocial aspects of female breast cancer in the Middle East and North Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6802. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17186802] [PMID]

- Dewi TK, Ruiter RA, Ardi R, Massar K. The role of psychosocial variables in breast self‐examination practice: Results from focus group discussions in Surabaya, Indonesia. Psycho-Oncology. 2022; 31(7):1169-77. [DOI:10.1002/pon.5905] [PMID]

- Kok G, van den Borne B, Mullen PD. Effectiveness of health education and health promotion: Meta-analyses of effect studies and determinants of effectiveness. Patient Education and Counseling. 1997; 30(1):19-27. [DOI:10.1016/S0738-3991(96)00953-6] [PMID]

- McLeod S. Constructivism [Internet]. 2023 [Updated 20 Aug 2023]. Available from: [Link]

- Badyal D, Singh T. Learning theories: The basics to learn in medical education. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research. 2017; 7(Suppl 1):S1-S3. [DOI:10.4103/ijabmr.IJABMR_385_17] [PMID]

- Western Governors University. What is constructivism? Utah: Western Governors University; 2020. [Link]

- Akpan VI, Igwe UA, Mpamah IB, Okoro CO. Social constructivism: Implications on teaching and learning. British Journal of Education. 2023; 8(8):49-56. [Link]

- No Author. Social constructivism theory [Internet].2023 [Updated 20 Aug 2023]. Available from: [Link]

- Vasconcelos C, Schneider-VoB, Susanne, Peppoloni S. Teaching geoethics: Resources for higher education. Porto: U. Porto; 2020. [Link]

- Kim Y. Application of social constructivism in medical education. Korean Medical Education Review. 2020; 22(2):85-92. [DOI:10.17496/kmer.2020.22.2.85]

- Topping K, Ehly S. Peer-assisted learning. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1998. [Link]

- Ten Cate O. Amee guide supplements: Peer-Assisted Learning: A planning and implementation framework. Guide supplement 30.5-viewpoint. Medical Teacher. 2009; 31(1):57-8. [DOI:10.1080/01421590802298173] [PMID]

- Tsai CL, Tu CH, Chen JC, Lane HY, Ma WF. Efficiency of an online health-promotion program in individuals with at-risk mental state during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11875. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182211875] [PMID]

- Ghahramani A, de Courten M, Prokofieva M. “The potential of social media in health promotion beyond creating awareness: An Integrative review.” BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):2402. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-14885-0] [PMID]

- Irish M, Kuso S, Simek M, Zeiler M, Potterton R, Musiat P, et al. Online prevention programmes for university students: Stakeholder perspectives from six European countries. European Journal of Public Health. 2021; 31(Supplement_1):i64-70. [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckab040] [PMID]

- Anderson T. The theory and practice of online learning. Edmonton: AU Press; 2008. [DOI:10.15215/aupress/9781897425084.01]

- Boroumand S, Stein MJ, Jay M, Shen JW, Hirsh M, Dharamsi S. Addressing the health advocate role in medical education. BMC Medical Education. 2020; 20(1):28. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-1938-7] [PMID]

- Minnick C, Soltany KA, Krishnamurthy S, Murray M, Strowd R, Montez K. Medical students value advocacy and health policy training in undergraduate medical education: A mixed methods study. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. 2025; 9(1):e61. [DOI:10.1017/cts.2025.35] [PMID]

- Røe Y, Johansen TS, Bruset EB. Empowering digital competence through peer-assisted learning and virtual reality in Health Professions Education. Frontiers in Education. 2025; 10:1550396. [DOI:10.3389/feduc.2025.1550396]

- Weiner LS, Nagel S, Irene Su H, Hurst S, Levy SS, Arredondo EM, et al. A remotely delivered, peer-led intervention to improve physical activity and quality of life in younger breast cancer survivors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2023; 46(4):578-93. [DOI:10.1007/s10865-022-00381-8] [PMID]

- Ranganath R, Muthusami J, Simon M, Mandal T, Kukkamulla MA. Female Medical and nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills regarding breast self-examination in Oman: A comparison between pre- and post-training. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. 2020; 17:37. [DOI:10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.37] [PMID]

- Diamond M. Change starts with awareness, yet it’s acceptance that defines your future. Chester: Diamond Consultants; 2023. [Link]

- World Health Organization. Health education: Theoretical concepts, effective strategies, and core competencies: A foundation document to guide capacity development of Health Educators. Cairo, Egypt: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2012. [Link]

- World Health Organization. Qualityrights materials for training, guidance and transformation: Qualityrights materials for training, guidance and transformation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Link]

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

- Awosogba T, Betancourt JR, Conyers FG, Estapé ES, Francois F, Gard SJ, et al. Prioritizing health disparities in medical education to improve care. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2013; 1287:17-30. [DOI:10.1111/nyas.12117] [PMID]

- Aitken C. Psychosocial aspects of disease and their management. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1984; 42(1-4):52-5. [DOI:10.1159/000287824] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2024/10/31 | Accepted: 2025/03/5 | Published: 2025/11/1

Received: 2024/10/31 | Accepted: 2025/03/5 | Published: 2025/11/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |