Volume 15, Issue 6 (Nov & Dec 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(6): 571-582 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: ΔΠΘ/ΕΗΔΕ/3825/243 19/12/2024

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Trigonis I, Zafeiroudi A, Tsartsapakis I, Kouli O, Karakatsanis K, Kouthouris C. Environmental and Psychosocial Barriers to Active Commuting and Physical Activity Among Urban Public School Teachers. J Research Health 2025; 15 (6) :571-582

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2808-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2808-en.html

Ioannis Trigonis1

, Aglaia Zafeiroudi2

, Aglaia Zafeiroudi2

, Ioannis Tsartsapakis3

, Ioannis Tsartsapakis3

, Olga Kouli4

, Olga Kouli4

, Konstantinos Karakatsanis5

, Konstantinos Karakatsanis5

, Charilaos Kouthouris2

, Charilaos Kouthouris2

, Aglaia Zafeiroudi2

, Aglaia Zafeiroudi2

, Ioannis Tsartsapakis3

, Ioannis Tsartsapakis3

, Olga Kouli4

, Olga Kouli4

, Konstantinos Karakatsanis5

, Konstantinos Karakatsanis5

, Charilaos Kouthouris2

, Charilaos Kouthouris2

1- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education, Sport Science and Occupational Therapy, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece. , itrigon@phyed.duth.gr

2- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education, Sport Science and Dietetics, University of Thessaly, Trikala, Greece.

3- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education and Sport Science, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Serres, Greece.

4- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education, Sport Science and Occupational Therapy, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece.

5- Department of Sport Organization and Management, School of Human Movement and Quality of Life Science, University of the Peloponnese, Sparta, Greece.

2- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education, Sport Science and Dietetics, University of Thessaly, Trikala, Greece.

3- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education and Sport Science, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Serres, Greece.

4- Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, School of Physical Education, Sport Science and Occupational Therapy, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece.

5- Department of Sport Organization and Management, School of Human Movement and Quality of Life Science, University of the Peloponnese, Sparta, Greece.

Keywords: Occupational health, Built environment, Public health, Transportation, Urban health, Motor activity

Full-Text [PDF 1003 kb]

(281 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2118 Views)

Full-Text: (253 Views)

Introduction

Public school teachers in urban settings occupy a strategic position within the school community, serving not only as educators but also as role models for healthy behaviors, including physical activity [1, 2]. Their daily routines and commuting choices have the potential to influence students, colleagues, and the broader educational environment [1, 3]. Nevertheless, the physical activity patterns and commuting behaviors of teachers themselves remain understudied, particularly in densely populated urban areas where structural and environmental constraints may discourage active lifestyles. Incorporating physical activity into routine activities, such as commuting to work, has been shown to contribute meaningfully to meeting health guidelines and improving physical and mental well-being [1, 2].

Globally, physical inactivity has emerged as a critical public health issue, contributing significantly to the rise of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular conditions, obesity, and type 2 diabetes [4]. According to the World Health Organizatiowhn (WHO), nearly one in four adults does not meet recommended physical activity levels [4]. Urbanization, sedentary occupations, and car-centric lifestyles further exacerbate these trends. In many European cities, especially in southern regions, the urban form often discourages active commuting due to dense traffic, lack of cycling infrastructure, and limited pedestrian-friendly design [4].

In Greece, these urban challenges are particularly acute. In cities, such as Athens and Thessaloniki, pedestrian mobility is severely hampered by narrow and poorly maintained sidewalks, fragmented public transportation systems, and an urban layout historically oriented towards private car use [5]. The built environment often lacks basic accessibility features, including continuous and obstacle-free walking paths, adequate lighting, and safe pedestrian crossings [5]. Furthermore, the absence of inclusive infrastructure disproportionately affects women, the elderly, and people with disabilities, limiting their autonomy and contributing to low rates of active commuting. Initiatives, such as “Walkable Athens,” have highlighted the urgent need for reimagining Greek cities through human-centered mobility design, aiming to make public space more accessible, safer, and more inviting for walking and cycling [5].

Active commuting, typically defined as walking, cycling, or other non-motorized modes of transportation to and from daily destinations, such as work or school, constitutes a highly accessible means of integrating physical activity into everyday life [2, 3]. It requires no special equipment or economic investment and can be adapted to a wide range of urban settings, making it particularly valuable in densely populated or lower-income areas. Numerous studies have established a strong link between active commuting and improved health outcomes, including better cardiovascular fitness, lower body mass index (BMI), and enhanced mental well-being [1, 3]. It has also been associated with increased autonomy, reduced levels of stress, and a greater sense of daily purpose [3].

Beyond individual health benefits, active commuting has significant implications for environmental sustainability and urban livability [2, 3]. By reducing reliance on motorized transport, active commuting contributes to lower greenhouse gas emissions, decreased traffic congestion, and improved air quality [2, 3]. These externalities are especially important in urban centers, where transport-related emissions are a leading contributor to environmental degradation. Moreover, active commuting fosters social interaction and neighborhood cohesion, creating safer and more vibrant communities [3]. Educational institutions and workplaces that promote active commuting culture, such as by offering secure bicycle parking or safe pedestrian infrastructure, can serve as catalysts for broader behavioral shifts toward sustainable mobility [1].

In the Greek context, active commuting remains significantly underdeveloped, despite the mild climate and relatively short urban distances that would otherwise support walking or cycling [5]. A nationwide lack of integrated urban planning, combined with poor sidewalk infrastructure, insufficient cycling lanes, and limited incentives for non-motorized transport, has hindered the widespread adoption of active commuting practices. In Athens, for instance, more than 65% of daily trips are conducted by private car, while pedestrian mobility is often obstructed by illegally parked vehicles, narrow pavements, and discontinuous walking paths [5]. In southern European countries, like Greece, active commuting is underutilized, with car dependency remaining high due to urban sprawl, fragmented transit systems, and cultural preferences for private vehicles [5]. Athens experienced an 80% increase in car ownership between 2008 and 2018, leading to chronic congestion and pollution. Despite recent investments in public transport infrastructure, many areas still lack pedestrian-friendly design. This creates significant barriers for individuals attempting to incorporate movement into their daily routines.

Among public school teachers, these barriers are especially relevant. A recent assessment by the Greek Ministry of Education revealed that the majority of educators in urban centers commute by car or motorcycle, citing time constraints, poor public transport connectivity, and safety concerns as major obstacles to walking or cycling [5]. Although some municipalities have piloted initiatives, such as “safe routes to school” and improvements in bicycle parking at educational institutions, the scale and impact of such programs remain limited. The promotion of active commuting among teachers, who serve as health role models, could offer a valuable entry point for broader community-level behavioral change [5].

However, the adoption of active commuting behaviors is strongly influenced by the built environment and perceived safety. Studies have shown that features, such as well-maintained sidewalks, bike lanes, street connectivity, and traffic calming infrastructure, significantly increase the likelihood of walking or cycling [4-6]. Conversely, fragmented pedestrian networks, lack of secure cycling routes, and poor lighting deter non-motorized travel, particularly among women who often report greater safety concerns [7, 8].

The educational workforce presents a valuable yet understudied group for examining commuting behavior [2] in urban Greece. Teachers often have consistent schedules and fixed locations, making them an ideal population for analyzing environmental and psychosocial barriers to active transport. Moreover, their influence within school communities positions them as potential agents of change [1] for promoting healthier commuting norms. As role models, educators can contribute meaningfully to broader school-based health promotion efforts, amplifying the impact of active commuting behaviors beyond the individual level.

This study examined the prevalence and characteristics of active commuting among public school teachers in Athens and Thessaloniki. It also explored the environmental and psychosocial barriers they face, aiming to provide evidence-based insights that can inform health promotion strategies and urban mobility planning in Greek metropolitan areas.

Contemporary public health frameworks increasingly emphasize the integration of active commuting within broader strategies for occupational well-being and sustainable urban development [9]. The WHO has long promoted workplace health programs as leverage points for behavioral change, particularly in addressing physical inactivity and chronic disease risk. At the same time, recent research emphasizes the need for intersectional approaches, such as gender-sensitive urban design, institutional support mechanisms, and intermodal commuting options, to overcome entrenched barriers to active transport and ensure equitable access to mobility opportunities [9].

Within this context, workplace-centered interventions, such as nature-based commuting initiatives, green breaks, and active travel incentives, have gained traction as viable pathways to enhancing both physical and mental health [9-12]. Systematic reviews confirm that green spaces and outdoor activity improve subjective well-being, reduce occupational stress, and foster creativity and engagement among employees. However, implementation remains limited by organizational inertia, resource constraints, and fragmented policy alignment across sectors. Focusing on a specific professional group, educators, this study contributes to the emerging discourse on embedding active commuting into institutional culture and design [9]. Teachers, due to their fixed schedules and social influence, represent a strategic population for piloting workplace wellness models that scale beyond individual behavior to promote systemic change.

Aim of the study

This study aimed to assess the prevalence and determinants of active commuting (walking or cycling) among public primary and secondary school educators in Athens and Thessaloniki cities. Specifically, it examined:

a) The relationships between gender, physical activity levels, and commuting behavior.

b) The influence of perceived environmental and psychosocial barriers.

c) The role of commuting distance in predicting active transport choices.

Research objectives and questions

To address these aims, the study was guided by the following research questions, which examine both behavioral patterns and contextual barriers to active commuting among urban educators:

What proportion of public school educators in Athens and Thessaloniki actively commute to work?

What are the most commonly perceived environmental and psychosocial barriers to active commuting among educators?

Is there an association between educators’ participation in physical activity during leisure time and their commuting mode?

Do active commuting behaviors differ significantly by gender, and how does commuting distance moderate this relationship?

Methods

Participants

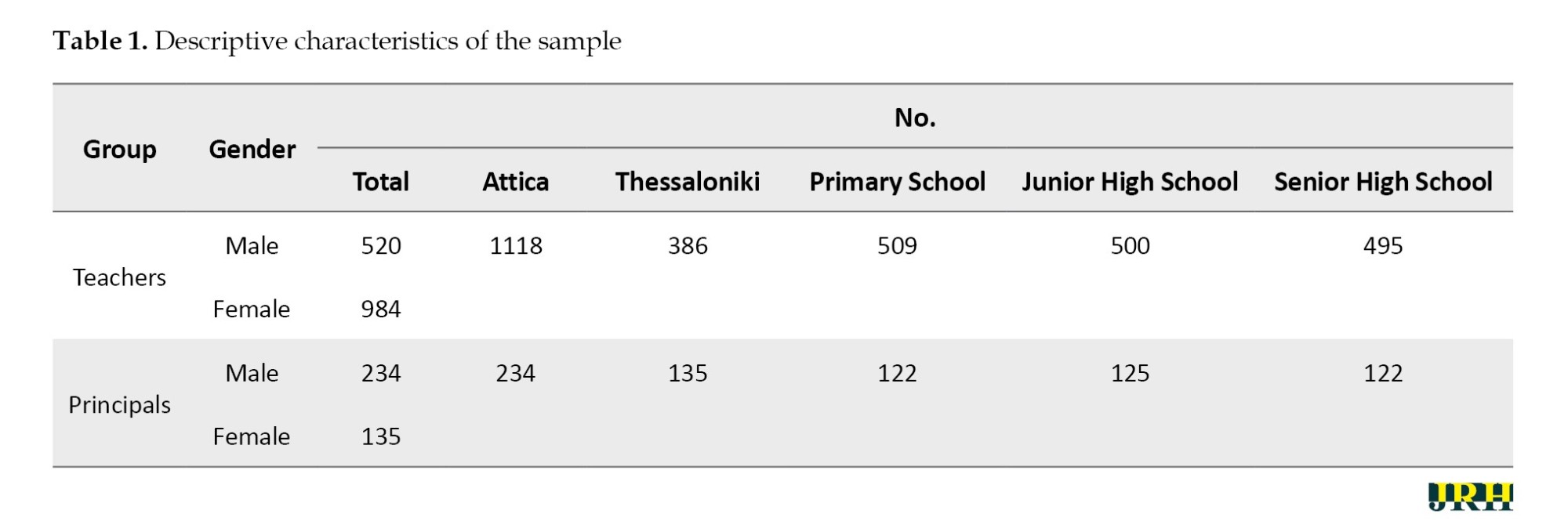

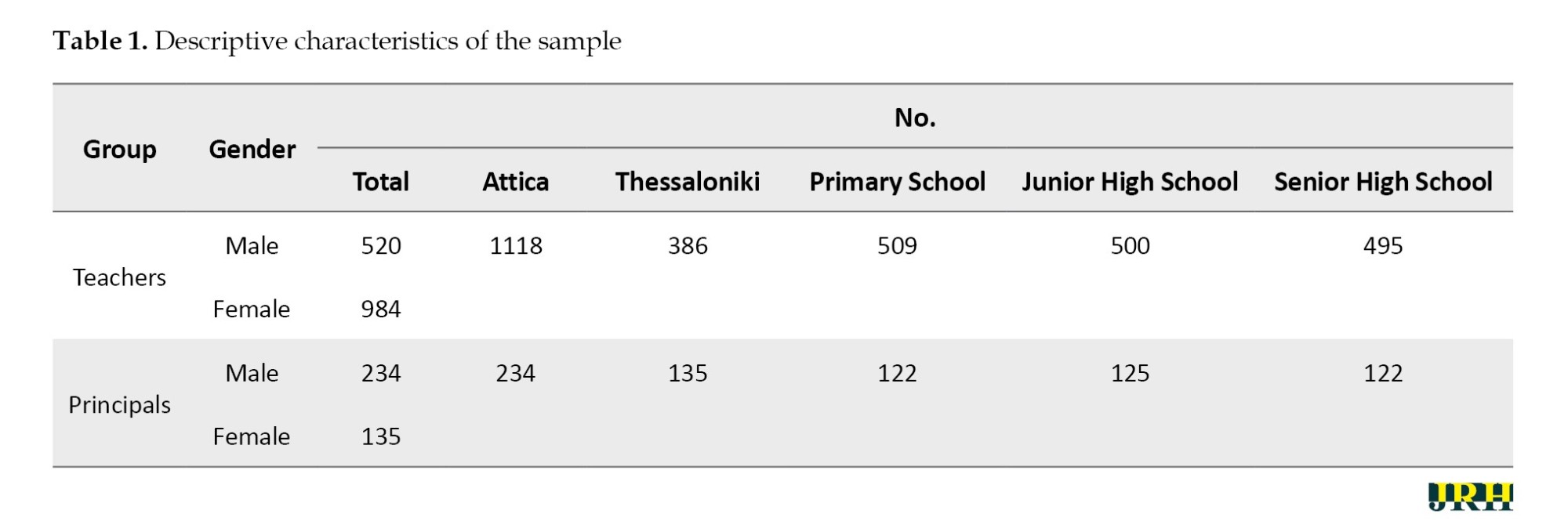

A total of 2069 questionnaires were distributed, and 1504 were completed and returned, yielding a response rate of approximately 72.7%. The final sample consisted of 1504 volunteer public school educators (520 men and 984 women) serving in primary schools, junior high (gymnasia), and senior high schools (lyceums). Specifically, 509 teachers were working in primary schools, 500 in junior high, and 495 in senior high schools. Additionally, 369 school principals (234 men and 135 women) participated, distributed as follows: 122 in primary, 125 in junior high, and 122 in senior high schools. All participants were recruited from public schools in the two most populous prefectures of Greece, Attica (n=246) and Thessaloniki (n=123). All institutions were publicly operated under the authority of the Ministry of Education. Eligibility included currently employed public educators aged 23–65 who resided in the Attica or Thessaloniki regions. Participants with incomplete questionnaires or inconsistent data (for example, missing location information) were excluded from the final analysis. The study was conducted between early 2024 and April 2025. Participant selection was conducted through stratified random sampling, ensuring proportional representation from each educational level, school type, and regional education directorate in both Attica and Thessaloniki. This sampling method was used to ensure proportional representation across key strata, including educational level (primary, junior high, senior high), school role (teacher or principal), and regional education directorates (Attica and Thessaloniki) (Table 1).

Instruments

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire consisting of demographics and main components, each selected for its relevance to the aims of the study and validated in previous international research literature:

Active commuting assessment scale: Adapted from Kerr et al [13] and standardized for the Greek population by Karakatsanis et al [14], this scale consisted of 2 items assessing the frequency of participation and mode of commuting (walking or cycling vs. motorized transport). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The internal consistency of this scale, as assessed by Cronbach’s α, was acceptable (α=0.72). This tool has been widely used in active mobility research and was selected for its reliability and conceptual clarity.

Barriers to active commuting scale: Also adapted from [13] and validated for use in the Greek population by [14], this 17-item scale evaluated the main perceived barriers to engaging in active commuting. Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). The items covered four thematic dimensions: (a) physical infrastructure and environmental barriers (e.g. lack of sidewalks or bike lanes), (b) safety concerns (e.g. traffic volume, existence of crime), (c) time availability and logistical difficulties (e.g. long distances, transporting materials), and (d) social and cultural perceptions (e.g. workplace expectations, family obligations). The internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (α=0.68).

Participation in organized physical activity: Participants indicated whether they regularly engaged in organized physical activity (e.g. team sports, fitness classes) lasting more than 30 consecutive minutes per session. They were asked to report frequency (sessions per week) and duration (minutes per session).

Demographic and lifestyle section: This section recorded gender, age, job role (teacher/principal), school level (primary, junior high, senior high), and location (Athens or Thessaloniki), along with general information about unstructured physical activity during a typical week.

Commuting distance: The distance between home and school was calculated using an online mapping application. Participants submitted their residential and school addresses, and the system estimated the travel distance in kilometers via standard pedestrian or cycling routes.

A brief pilot study was conducted with 25 school educators to assess the validity, clarity, relevance, and cultural appropriateness of the questionnaire. Minor linguistic adjustments were made based on feedback, but no structural modifications were considered necessary.

Data collection procedure

Following official approval from the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, the researcher contacted school principals in the Attica and Thessaloniki prefectures. Meetings were held to explain the purpose of the study and coordinate the data collection process. Data were collected using a structured, self-administered paper questionnaire, which was distributed and completed in person at each participating school. The research team coordinated with school principals to schedule the data collection sessions. Trained research assistants were present during distribution to provide instructions, clarify questions, and ensure anonymity and voluntary participation. Prior to completing the questionnaire, all participants received a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose and confidentiality procedures, and written informed consent was obtained. All procedures adhered to national ethical standards and were approved by the Ministry of Education. In addition, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Democritus University of Thrace.

The questionnaire captured participants’ demographic characteristics, commuting behavior to and from school, engagement in organized physical activity during the current academic year, the amount of weekly unstructured physical activity, perceived barriers to active commuting, and general attitudes toward physical activity. To classify commuting behavior, the following operational criteria were applied: a) Active commuters: those who walked or cycled to and from school more than five times per week (i.e. >5 out of 10 trips); b) Mixed commuters: Those who used active transport for exactly five trips and motorized transport for the remaining five; c) Passive commuters: those who used motorized transport for more than five trips per week. These classifications provided the basis for further statistical analysis regarding associations between commuting patterns and various demographic and behavioral factors.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 28.0. Descriptive statistics were initially computed to summarize the demographic characteristics of the participants and to provide frequency distributions and measures of central tendency for key study variables. These included percentages, Mean±SD, where appropriate.

Prior to conducting parametric tests, assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested and confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene’s tests, respectively. No violations of these assumptions were observed. To examine potential group differences based on gender, educational level, and commuting behavior, independent samples t-tests were employed for binary comparisons, and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to assess differences across three or more groups. Where significant main effects were observed in ANOVA, post-hoc comparisons were conducted to determine the specific group differences.

In order to explore the strength and direction of associations between continuous variables, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used. This analysis aimed to detect significant positive or negative correlations between active commuting frequency, levels of physical activity, distance to school, and perceived barriers.

A significance level of P<0.05 was adopted for all inferential tests.

Results

Effects of gender and city on active commuting

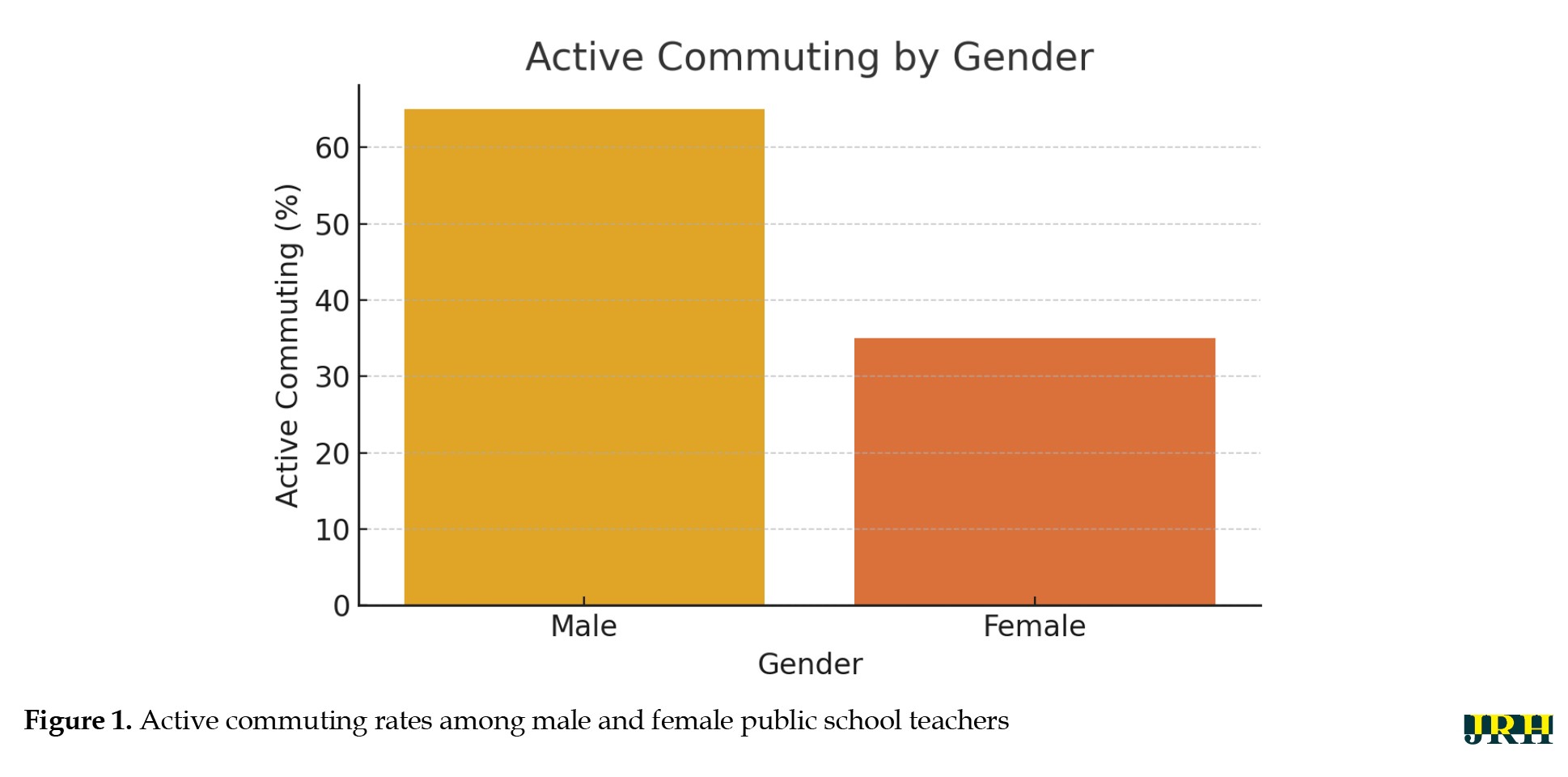

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of gender (male, female) and city of employment (Athens, Thessaloniki) on the frequency of active commuting among educators. The analysis revealed a statistically significant main effect of gender F1, 546=264.32, P<0.001), indicating that male teachers reported significantly higher levels of active commuting compared to their female counterparts, regardless of city.

However, there was no significant main effect of city (F1, 546=0.24, P>0.05), suggesting that residing in Athens versus Thessaloniki did not independently affect commuting behavior. No significant interaction effect between gender and city was found, indicating that the gender differences in active commuting were consistent across both cities.

Further comparisons within gender groups confirmed the absence of significant differences among men based on city of residence and employment (F1, 546=0.18, P>0.05), and similarly among women (F1, 546=0.24, P>0.05). These differences are presented in Figure 1.

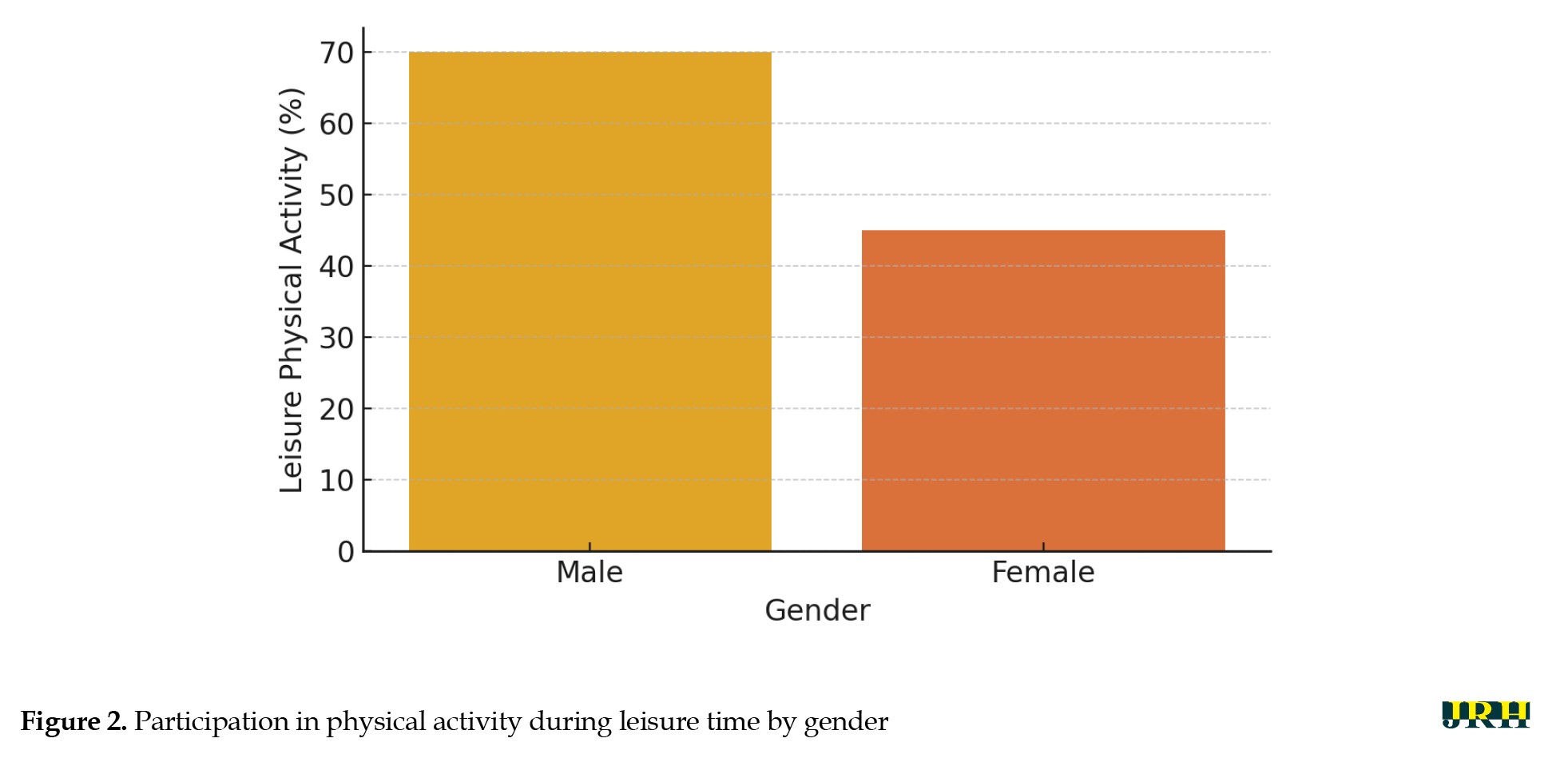

Participation in physical activity during leisure time

Similar gender-based disparities were observed in physical activity during leisure time. Male teachers from both Athens and Thessaloniki reported higher participation rates in recreational or athletic activities compared to female teachers (F1, 546=167.32, P<0.001). No statistically significant differences were found within the male or female subgroups based on city of residence. These results are presented in Figure 2.

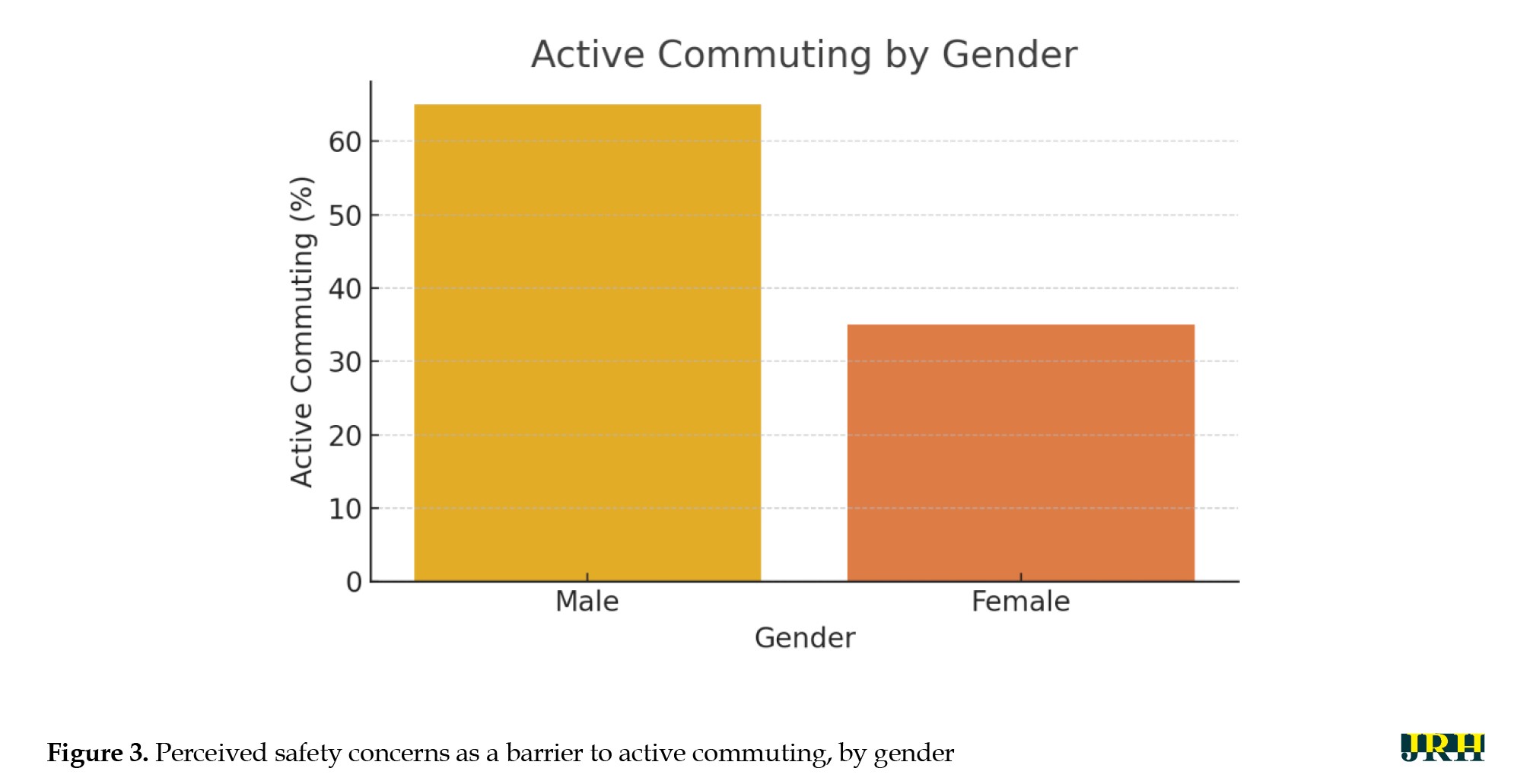

Perceived barriers to active commuting

The most frequently cited barriers to active commuting included lack of motivation, concerns about safety (especially among potential cyclists), inadequate infrastructure (e.g. absence of bike lanes, sidewalks, or secure bicycle parking), poor physical condition, cost of purchasing and maintaining equipment, adverse weather conditions, and lack of prior consideration.

A two-way ANOVA identified significant differences in perceived barriers based on gender (F1, 546 =187.32, P<0.001). In particular, female teachers reported significantly higher levels of concern about personal safety when commuting actively, a trend observed consistently in both Athens and Thessaloniki. These differences are presented in Figure 3.

Correlations between distance and active commuting

Pearson correlation coefficients indicated a strong positive correlation between commuting distance and commuting mode among male teachers (r=0.665, P<0.001). Specifically, men whose residence was within 1,000 meters of the school were significantly more likely to commute actively than those living farther away, in both cities.

In contrast, the same relationship was not statistically significant for female teachers (r=0.584, P=0.07). Although the correlation was moderate (r=0.584), it did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07), suggesting that distance alone may not predict active commuting behavior among female teachers.

Association between activity during leisure time and active commuting

A strong positive correlation was also observed between participation in structured physical activity during leisure time and the frequency of active commuting. Educators, both male and female, who reported engaging in physical activity for at least 30 minutes per session, three or more times per week, were significantly more likely to commute actively (r=0.789, P<0.001). This relationship held true across both genders and both urban locations.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlighted the multifaceted barriers to active commuting among educators, emphasizing both individual-level factors and environmental determinants. Consistent with previous research [14, 15], distance to the workplace emerged as a primary deterrent, particularly when exceeding the walkable or cyclable threshold of 3 km. Additional constraints included time limitations, poor physical condition, lack of infrastructure (such as bike lanes, sidewalks, storage facilities), perceived risk of injury, and adverse weather conditions.

Male teachers were more likely than females to engage in active commuting, a pattern consistent with documented gender disparities in perceived neighborhood safety and commuting confidence [7]. These gender differences may reflect broader sociocultural perceptions of vulnerability, with female educators expressing heightened concern regarding personal safety. These findings support the need for neighborhood safety enhancements, such as improved lighting, better street connectivity, and increased visual openness, as prerequisites for promoting walking and cycling among women [8].

Furthermore, the study found that proximity was a key predictor of active commuting, particularly among male participants. Educators residing within one kilometer of their schools were significantly more likely to commute actively. However, distance did not significantly predict commuting behavior among female participants, indicating that psychosocial barriers may play a more decisive role. Importantly, higher engagement in organized or physical activity during leisure time was positively associated with active commuting, supporting prior findings that such behavior is embedded within a broader health-oriented lifestyle [1, 3].

Environmental and policy-related implications are clearly articulated. Consistent with the literature [4, 7, 15], features, such as sidewalk quality, traffic calming, street aesthetics, and transit access are positively linked to active transport choices. This supports the idea that neighborhoods with greater walkability, land-use diversity, and urban density promote more sustainable and health-enhancing mobility patterns [6, 5].

At the community level, active commuting contributes to broader benefits, such as reduced traffic congestion, lower emissions, and greater social interaction, which enhance neighborhood cohesion and public well-being [1]. Individuals who commute actively are more likely to walk or cycle for other purposes, reinforcing a lifestyle approach rather than isolated choices [2].

This study aligns with global trends showing that active transport is underutilized for commutes over 3 km. Urban planning and public health initiatives must focus on reducing car dependency and promoting safe, accessible, and culturally accepted walking and cycling. Suggested strategies include school-based walking programs, workplace-based interventions, and investments in infrastructure [11, 12].

From a workplace perspective, promoting active commuting is both feasible and beneficial. Prior studies show that commuting experiences affect mental and physical health, job satisfaction, and productivity [16-18]. Employees who commute actively report greater well-being and resilience. This highlights the role of commuting in overall occupational health.

Gender-specific responses to commuting stress also deserve attention. Women are more affected by unsafe or stressful commutes, reinforcing the need for gender-sensitive planning [19]. Commuting also influences social and emotional patterns, family routines, and social interaction [11].

Changing commuting behavior requires systemic approaches. Raising awareness alone is insufficient. Comprehensive strategies that address physical, environmental, psychological, and cultural factors are needed to enable long-term behavioral shifts. Interventions should be inclusive, policy-supported, and infrastructure-based.

The study provides actionable insights for urban and health policy. Key recommendations include the development of gender-sensitive infrastructure (for example, protected sidewalks and bike lanes near schools), integration of active transport into national and municipal mobility plans, and school-centered health promotion initiatives. Employers can support behavior change through secure bike parking, flexible hours, and facilities like showers or lockers. For longer commutes, the combined use of active transport and public transit should be encouraged through incentives (like subsidized passes).

Environmental barriers, especially safety, must be addressed with targeted infrastructure investments. Digital tools, geographic information systems (GIS), and route optimization can support informed commuting decisions. Events, like “active commuting days” and employer-led campaigns, can reinforce engagement and motivation [4, 20, 21]. Supportive organizational cultures can enhance employee wellness, productivity, and retention. Promoting active commuting is thus not only a public health issue but also a strategic investment in institutional performance and sustainability [1, 22-25].

By focusing on urban school educators, this study offers valuable insights into how commuting behaviors are shaped by gender, safety perceptions, environmental factors, and lifestyle choices. Its contributions lie in integrating environmental and psychosocial perspectives and providing practical, context-sensitive recommendations for health and urban policy. The study builds on existing theory while addressing a population group often overlooked in active commuting research. Its alignment with global sustainability and workplace wellness agendas emphasizes its policy relevance for both national and local stakeholders.

Limitations and future research

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. While significant associations were identified between commuting behavior and factors, such as gender, distance, and physical activity, longitudinal research is necessary to determine how these relationships evolve over time or in response to policy and infrastructural changes. Second, the study relied on self-reported data for commuting patterns and physical activity, which may be subject to recall error and social desirability bias. In particular, participants may have overreported active commuting due to social expectations linked to their professional identity as educators and role models. The absence of objective metrics to verify responses (such as GPS data or accelerometers) limits the precision of behavioral assessments.

Third, potential seasonal or academic calendar effects were not accounted for. The data were collected between early 2024 and April 2025, a period that may include fluctuations in commuting behavior due to weather, school breaks, or exam periods. These temporal variables could have influenced participants’ activity patterns but were not controlled for in the study design. Additionally, the scope was limited to public school educators in two major urban centers (Athens and Thessaloniki). Findings may not generalize to rural areas, different professional sectors, or populations with varying socioeconomic or cultural backgrounds. Expanding future research to include diverse geographic and occupational contexts is necessary to draw broader conclusions.

From a methodological standpoint, future studies should incorporate objective measurement tools, such as GPS-tracked commuting routes, wearable activity monitors, or direct observational techniques, to triangulate and validate self-reported behavior. Furthermore, institutional and policy-level factors (for example, availability of bicycle parking, flexible work hours, commuting subsidies) were not examined in this study but may play a critical role in shaping active commuting behavior and warrant closer investigation.

Finally, future research should explore the relationships between commuting behavior and concrete health outcomes, including BMI, metabolic health indicators, and psychological well-being. This is particularly relevant for populations at higher risk of sedentary lifestyles or chronic illness. A deeper understanding of the psychosocial mechanisms, such as motivation, risk perception, and habit formation, will also be essential for designing equitable, context-sensitive, and effective interventions.

Conclusion

This study highlights that active commuting among public school educators in Athens and Thessaloniki is significantly shaped by gender, distance to school, perceived safety, and prior engagement in physical activity. Female participants were less likely to commute actively, particularly when environmental safety concerns were high, while educators who engaged in organized or leisure-time physical activity were more inclined to walk or cycle to work. These findings suggest that addressing psychosocial barriers, particularly among women, should be prioritized alongside infrastructural improvements.

Based on these insights, we recommend targeted urban planning interventions, such as installing protected sidewalks, bike lanes, and improved lighting near school zones. Additionally, public education campaigns and school-based initiatives can help shift cultural norms and perceptions around commuting. At the institutional level, employers should consider providing incentives, like secure bike parking, flexible schedules, and wellness programs, to encourage active transport. Policymakers should also integrate active commuting strategies into broader urban mobility and health promotion frameworks. By tailoring interventions to local barriers and population needs, cities can foster healthier, safer, and more sustainable commuting behaviors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In accordance with ethical research standards, all participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their involvement, and the confidentiality of their responses. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Democritus University of Thrace (Code: ΔΠΘ/ΕΗΔΕ/3825/243; Dated: 19/12/2024). This study was approved by the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs (Protocol Nos.: Φ15/782/126370/Γ1 and 139378/Γ2).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the school principals and public school teachers who participated in the study for their time and valuable input. The authors are also grateful to the regional education authorities in Attica and Thessaloniki for facilitating access to the participating schools.

References

Public school teachers in urban settings occupy a strategic position within the school community, serving not only as educators but also as role models for healthy behaviors, including physical activity [1, 2]. Their daily routines and commuting choices have the potential to influence students, colleagues, and the broader educational environment [1, 3]. Nevertheless, the physical activity patterns and commuting behaviors of teachers themselves remain understudied, particularly in densely populated urban areas where structural and environmental constraints may discourage active lifestyles. Incorporating physical activity into routine activities, such as commuting to work, has been shown to contribute meaningfully to meeting health guidelines and improving physical and mental well-being [1, 2].

Globally, physical inactivity has emerged as a critical public health issue, contributing significantly to the rise of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular conditions, obesity, and type 2 diabetes [4]. According to the World Health Organizatiowhn (WHO), nearly one in four adults does not meet recommended physical activity levels [4]. Urbanization, sedentary occupations, and car-centric lifestyles further exacerbate these trends. In many European cities, especially in southern regions, the urban form often discourages active commuting due to dense traffic, lack of cycling infrastructure, and limited pedestrian-friendly design [4].

In Greece, these urban challenges are particularly acute. In cities, such as Athens and Thessaloniki, pedestrian mobility is severely hampered by narrow and poorly maintained sidewalks, fragmented public transportation systems, and an urban layout historically oriented towards private car use [5]. The built environment often lacks basic accessibility features, including continuous and obstacle-free walking paths, adequate lighting, and safe pedestrian crossings [5]. Furthermore, the absence of inclusive infrastructure disproportionately affects women, the elderly, and people with disabilities, limiting their autonomy and contributing to low rates of active commuting. Initiatives, such as “Walkable Athens,” have highlighted the urgent need for reimagining Greek cities through human-centered mobility design, aiming to make public space more accessible, safer, and more inviting for walking and cycling [5].

Active commuting, typically defined as walking, cycling, or other non-motorized modes of transportation to and from daily destinations, such as work or school, constitutes a highly accessible means of integrating physical activity into everyday life [2, 3]. It requires no special equipment or economic investment and can be adapted to a wide range of urban settings, making it particularly valuable in densely populated or lower-income areas. Numerous studies have established a strong link between active commuting and improved health outcomes, including better cardiovascular fitness, lower body mass index (BMI), and enhanced mental well-being [1, 3]. It has also been associated with increased autonomy, reduced levels of stress, and a greater sense of daily purpose [3].

Beyond individual health benefits, active commuting has significant implications for environmental sustainability and urban livability [2, 3]. By reducing reliance on motorized transport, active commuting contributes to lower greenhouse gas emissions, decreased traffic congestion, and improved air quality [2, 3]. These externalities are especially important in urban centers, where transport-related emissions are a leading contributor to environmental degradation. Moreover, active commuting fosters social interaction and neighborhood cohesion, creating safer and more vibrant communities [3]. Educational institutions and workplaces that promote active commuting culture, such as by offering secure bicycle parking or safe pedestrian infrastructure, can serve as catalysts for broader behavioral shifts toward sustainable mobility [1].

In the Greek context, active commuting remains significantly underdeveloped, despite the mild climate and relatively short urban distances that would otherwise support walking or cycling [5]. A nationwide lack of integrated urban planning, combined with poor sidewalk infrastructure, insufficient cycling lanes, and limited incentives for non-motorized transport, has hindered the widespread adoption of active commuting practices. In Athens, for instance, more than 65% of daily trips are conducted by private car, while pedestrian mobility is often obstructed by illegally parked vehicles, narrow pavements, and discontinuous walking paths [5]. In southern European countries, like Greece, active commuting is underutilized, with car dependency remaining high due to urban sprawl, fragmented transit systems, and cultural preferences for private vehicles [5]. Athens experienced an 80% increase in car ownership between 2008 and 2018, leading to chronic congestion and pollution. Despite recent investments in public transport infrastructure, many areas still lack pedestrian-friendly design. This creates significant barriers for individuals attempting to incorporate movement into their daily routines.

Among public school teachers, these barriers are especially relevant. A recent assessment by the Greek Ministry of Education revealed that the majority of educators in urban centers commute by car or motorcycle, citing time constraints, poor public transport connectivity, and safety concerns as major obstacles to walking or cycling [5]. Although some municipalities have piloted initiatives, such as “safe routes to school” and improvements in bicycle parking at educational institutions, the scale and impact of such programs remain limited. The promotion of active commuting among teachers, who serve as health role models, could offer a valuable entry point for broader community-level behavioral change [5].

However, the adoption of active commuting behaviors is strongly influenced by the built environment and perceived safety. Studies have shown that features, such as well-maintained sidewalks, bike lanes, street connectivity, and traffic calming infrastructure, significantly increase the likelihood of walking or cycling [4-6]. Conversely, fragmented pedestrian networks, lack of secure cycling routes, and poor lighting deter non-motorized travel, particularly among women who often report greater safety concerns [7, 8].

The educational workforce presents a valuable yet understudied group for examining commuting behavior [2] in urban Greece. Teachers often have consistent schedules and fixed locations, making them an ideal population for analyzing environmental and psychosocial barriers to active transport. Moreover, their influence within school communities positions them as potential agents of change [1] for promoting healthier commuting norms. As role models, educators can contribute meaningfully to broader school-based health promotion efforts, amplifying the impact of active commuting behaviors beyond the individual level.

This study examined the prevalence and characteristics of active commuting among public school teachers in Athens and Thessaloniki. It also explored the environmental and psychosocial barriers they face, aiming to provide evidence-based insights that can inform health promotion strategies and urban mobility planning in Greek metropolitan areas.

Contemporary public health frameworks increasingly emphasize the integration of active commuting within broader strategies for occupational well-being and sustainable urban development [9]. The WHO has long promoted workplace health programs as leverage points for behavioral change, particularly in addressing physical inactivity and chronic disease risk. At the same time, recent research emphasizes the need for intersectional approaches, such as gender-sensitive urban design, institutional support mechanisms, and intermodal commuting options, to overcome entrenched barriers to active transport and ensure equitable access to mobility opportunities [9].

Within this context, workplace-centered interventions, such as nature-based commuting initiatives, green breaks, and active travel incentives, have gained traction as viable pathways to enhancing both physical and mental health [9-12]. Systematic reviews confirm that green spaces and outdoor activity improve subjective well-being, reduce occupational stress, and foster creativity and engagement among employees. However, implementation remains limited by organizational inertia, resource constraints, and fragmented policy alignment across sectors. Focusing on a specific professional group, educators, this study contributes to the emerging discourse on embedding active commuting into institutional culture and design [9]. Teachers, due to their fixed schedules and social influence, represent a strategic population for piloting workplace wellness models that scale beyond individual behavior to promote systemic change.

Aim of the study

This study aimed to assess the prevalence and determinants of active commuting (walking or cycling) among public primary and secondary school educators in Athens and Thessaloniki cities. Specifically, it examined:

a) The relationships between gender, physical activity levels, and commuting behavior.

b) The influence of perceived environmental and psychosocial barriers.

c) The role of commuting distance in predicting active transport choices.

Research objectives and questions

To address these aims, the study was guided by the following research questions, which examine both behavioral patterns and contextual barriers to active commuting among urban educators:

What proportion of public school educators in Athens and Thessaloniki actively commute to work?

What are the most commonly perceived environmental and psychosocial barriers to active commuting among educators?

Is there an association between educators’ participation in physical activity during leisure time and their commuting mode?

Do active commuting behaviors differ significantly by gender, and how does commuting distance moderate this relationship?

Methods

Participants

A total of 2069 questionnaires were distributed, and 1504 were completed and returned, yielding a response rate of approximately 72.7%. The final sample consisted of 1504 volunteer public school educators (520 men and 984 women) serving in primary schools, junior high (gymnasia), and senior high schools (lyceums). Specifically, 509 teachers were working in primary schools, 500 in junior high, and 495 in senior high schools. Additionally, 369 school principals (234 men and 135 women) participated, distributed as follows: 122 in primary, 125 in junior high, and 122 in senior high schools. All participants were recruited from public schools in the two most populous prefectures of Greece, Attica (n=246) and Thessaloniki (n=123). All institutions were publicly operated under the authority of the Ministry of Education. Eligibility included currently employed public educators aged 23–65 who resided in the Attica or Thessaloniki regions. Participants with incomplete questionnaires or inconsistent data (for example, missing location information) were excluded from the final analysis. The study was conducted between early 2024 and April 2025. Participant selection was conducted through stratified random sampling, ensuring proportional representation from each educational level, school type, and regional education directorate in both Attica and Thessaloniki. This sampling method was used to ensure proportional representation across key strata, including educational level (primary, junior high, senior high), school role (teacher or principal), and regional education directorates (Attica and Thessaloniki) (Table 1).

Instruments

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire consisting of demographics and main components, each selected for its relevance to the aims of the study and validated in previous international research literature:

Active commuting assessment scale: Adapted from Kerr et al [13] and standardized for the Greek population by Karakatsanis et al [14], this scale consisted of 2 items assessing the frequency of participation and mode of commuting (walking or cycling vs. motorized transport). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The internal consistency of this scale, as assessed by Cronbach’s α, was acceptable (α=0.72). This tool has been widely used in active mobility research and was selected for its reliability and conceptual clarity.

Barriers to active commuting scale: Also adapted from [13] and validated for use in the Greek population by [14], this 17-item scale evaluated the main perceived barriers to engaging in active commuting. Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). The items covered four thematic dimensions: (a) physical infrastructure and environmental barriers (e.g. lack of sidewalks or bike lanes), (b) safety concerns (e.g. traffic volume, existence of crime), (c) time availability and logistical difficulties (e.g. long distances, transporting materials), and (d) social and cultural perceptions (e.g. workplace expectations, family obligations). The internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (α=0.68).

Participation in organized physical activity: Participants indicated whether they regularly engaged in organized physical activity (e.g. team sports, fitness classes) lasting more than 30 consecutive minutes per session. They were asked to report frequency (sessions per week) and duration (minutes per session).

Demographic and lifestyle section: This section recorded gender, age, job role (teacher/principal), school level (primary, junior high, senior high), and location (Athens or Thessaloniki), along with general information about unstructured physical activity during a typical week.

Commuting distance: The distance between home and school was calculated using an online mapping application. Participants submitted their residential and school addresses, and the system estimated the travel distance in kilometers via standard pedestrian or cycling routes.

A brief pilot study was conducted with 25 school educators to assess the validity, clarity, relevance, and cultural appropriateness of the questionnaire. Minor linguistic adjustments were made based on feedback, but no structural modifications were considered necessary.

Data collection procedure

Following official approval from the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, the researcher contacted school principals in the Attica and Thessaloniki prefectures. Meetings were held to explain the purpose of the study and coordinate the data collection process. Data were collected using a structured, self-administered paper questionnaire, which was distributed and completed in person at each participating school. The research team coordinated with school principals to schedule the data collection sessions. Trained research assistants were present during distribution to provide instructions, clarify questions, and ensure anonymity and voluntary participation. Prior to completing the questionnaire, all participants received a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose and confidentiality procedures, and written informed consent was obtained. All procedures adhered to national ethical standards and were approved by the Ministry of Education. In addition, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Democritus University of Thrace.

The questionnaire captured participants’ demographic characteristics, commuting behavior to and from school, engagement in organized physical activity during the current academic year, the amount of weekly unstructured physical activity, perceived barriers to active commuting, and general attitudes toward physical activity. To classify commuting behavior, the following operational criteria were applied: a) Active commuters: those who walked or cycled to and from school more than five times per week (i.e. >5 out of 10 trips); b) Mixed commuters: Those who used active transport for exactly five trips and motorized transport for the remaining five; c) Passive commuters: those who used motorized transport for more than five trips per week. These classifications provided the basis for further statistical analysis regarding associations between commuting patterns and various demographic and behavioral factors.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 28.0. Descriptive statistics were initially computed to summarize the demographic characteristics of the participants and to provide frequency distributions and measures of central tendency for key study variables. These included percentages, Mean±SD, where appropriate.

Prior to conducting parametric tests, assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested and confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene’s tests, respectively. No violations of these assumptions were observed. To examine potential group differences based on gender, educational level, and commuting behavior, independent samples t-tests were employed for binary comparisons, and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to assess differences across three or more groups. Where significant main effects were observed in ANOVA, post-hoc comparisons were conducted to determine the specific group differences.

In order to explore the strength and direction of associations between continuous variables, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used. This analysis aimed to detect significant positive or negative correlations between active commuting frequency, levels of physical activity, distance to school, and perceived barriers.

A significance level of P<0.05 was adopted for all inferential tests.

Results

Effects of gender and city on active commuting

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of gender (male, female) and city of employment (Athens, Thessaloniki) on the frequency of active commuting among educators. The analysis revealed a statistically significant main effect of gender F1, 546=264.32, P<0.001), indicating that male teachers reported significantly higher levels of active commuting compared to their female counterparts, regardless of city.

However, there was no significant main effect of city (F1, 546=0.24, P>0.05), suggesting that residing in Athens versus Thessaloniki did not independently affect commuting behavior. No significant interaction effect between gender and city was found, indicating that the gender differences in active commuting were consistent across both cities.

Further comparisons within gender groups confirmed the absence of significant differences among men based on city of residence and employment (F1, 546=0.18, P>0.05), and similarly among women (F1, 546=0.24, P>0.05). These differences are presented in Figure 1.

Participation in physical activity during leisure time

Similar gender-based disparities were observed in physical activity during leisure time. Male teachers from both Athens and Thessaloniki reported higher participation rates in recreational or athletic activities compared to female teachers (F1, 546=167.32, P<0.001). No statistically significant differences were found within the male or female subgroups based on city of residence. These results are presented in Figure 2.

Perceived barriers to active commuting

The most frequently cited barriers to active commuting included lack of motivation, concerns about safety (especially among potential cyclists), inadequate infrastructure (e.g. absence of bike lanes, sidewalks, or secure bicycle parking), poor physical condition, cost of purchasing and maintaining equipment, adverse weather conditions, and lack of prior consideration.

A two-way ANOVA identified significant differences in perceived barriers based on gender (F1, 546 =187.32, P<0.001). In particular, female teachers reported significantly higher levels of concern about personal safety when commuting actively, a trend observed consistently in both Athens and Thessaloniki. These differences are presented in Figure 3.

Correlations between distance and active commuting

Pearson correlation coefficients indicated a strong positive correlation between commuting distance and commuting mode among male teachers (r=0.665, P<0.001). Specifically, men whose residence was within 1,000 meters of the school were significantly more likely to commute actively than those living farther away, in both cities.

In contrast, the same relationship was not statistically significant for female teachers (r=0.584, P=0.07). Although the correlation was moderate (r=0.584), it did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07), suggesting that distance alone may not predict active commuting behavior among female teachers.

Association between activity during leisure time and active commuting

A strong positive correlation was also observed between participation in structured physical activity during leisure time and the frequency of active commuting. Educators, both male and female, who reported engaging in physical activity for at least 30 minutes per session, three or more times per week, were significantly more likely to commute actively (r=0.789, P<0.001). This relationship held true across both genders and both urban locations.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlighted the multifaceted barriers to active commuting among educators, emphasizing both individual-level factors and environmental determinants. Consistent with previous research [14, 15], distance to the workplace emerged as a primary deterrent, particularly when exceeding the walkable or cyclable threshold of 3 km. Additional constraints included time limitations, poor physical condition, lack of infrastructure (such as bike lanes, sidewalks, storage facilities), perceived risk of injury, and adverse weather conditions.

Male teachers were more likely than females to engage in active commuting, a pattern consistent with documented gender disparities in perceived neighborhood safety and commuting confidence [7]. These gender differences may reflect broader sociocultural perceptions of vulnerability, with female educators expressing heightened concern regarding personal safety. These findings support the need for neighborhood safety enhancements, such as improved lighting, better street connectivity, and increased visual openness, as prerequisites for promoting walking and cycling among women [8].

Furthermore, the study found that proximity was a key predictor of active commuting, particularly among male participants. Educators residing within one kilometer of their schools were significantly more likely to commute actively. However, distance did not significantly predict commuting behavior among female participants, indicating that psychosocial barriers may play a more decisive role. Importantly, higher engagement in organized or physical activity during leisure time was positively associated with active commuting, supporting prior findings that such behavior is embedded within a broader health-oriented lifestyle [1, 3].

Environmental and policy-related implications are clearly articulated. Consistent with the literature [4, 7, 15], features, such as sidewalk quality, traffic calming, street aesthetics, and transit access are positively linked to active transport choices. This supports the idea that neighborhoods with greater walkability, land-use diversity, and urban density promote more sustainable and health-enhancing mobility patterns [6, 5].

At the community level, active commuting contributes to broader benefits, such as reduced traffic congestion, lower emissions, and greater social interaction, which enhance neighborhood cohesion and public well-being [1]. Individuals who commute actively are more likely to walk or cycle for other purposes, reinforcing a lifestyle approach rather than isolated choices [2].

This study aligns with global trends showing that active transport is underutilized for commutes over 3 km. Urban planning and public health initiatives must focus on reducing car dependency and promoting safe, accessible, and culturally accepted walking and cycling. Suggested strategies include school-based walking programs, workplace-based interventions, and investments in infrastructure [11, 12].

From a workplace perspective, promoting active commuting is both feasible and beneficial. Prior studies show that commuting experiences affect mental and physical health, job satisfaction, and productivity [16-18]. Employees who commute actively report greater well-being and resilience. This highlights the role of commuting in overall occupational health.

Gender-specific responses to commuting stress also deserve attention. Women are more affected by unsafe or stressful commutes, reinforcing the need for gender-sensitive planning [19]. Commuting also influences social and emotional patterns, family routines, and social interaction [11].

Changing commuting behavior requires systemic approaches. Raising awareness alone is insufficient. Comprehensive strategies that address physical, environmental, psychological, and cultural factors are needed to enable long-term behavioral shifts. Interventions should be inclusive, policy-supported, and infrastructure-based.

The study provides actionable insights for urban and health policy. Key recommendations include the development of gender-sensitive infrastructure (for example, protected sidewalks and bike lanes near schools), integration of active transport into national and municipal mobility plans, and school-centered health promotion initiatives. Employers can support behavior change through secure bike parking, flexible hours, and facilities like showers or lockers. For longer commutes, the combined use of active transport and public transit should be encouraged through incentives (like subsidized passes).

Environmental barriers, especially safety, must be addressed with targeted infrastructure investments. Digital tools, geographic information systems (GIS), and route optimization can support informed commuting decisions. Events, like “active commuting days” and employer-led campaigns, can reinforce engagement and motivation [4, 20, 21]. Supportive organizational cultures can enhance employee wellness, productivity, and retention. Promoting active commuting is thus not only a public health issue but also a strategic investment in institutional performance and sustainability [1, 22-25].

By focusing on urban school educators, this study offers valuable insights into how commuting behaviors are shaped by gender, safety perceptions, environmental factors, and lifestyle choices. Its contributions lie in integrating environmental and psychosocial perspectives and providing practical, context-sensitive recommendations for health and urban policy. The study builds on existing theory while addressing a population group often overlooked in active commuting research. Its alignment with global sustainability and workplace wellness agendas emphasizes its policy relevance for both national and local stakeholders.

Limitations and future research

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. While significant associations were identified between commuting behavior and factors, such as gender, distance, and physical activity, longitudinal research is necessary to determine how these relationships evolve over time or in response to policy and infrastructural changes. Second, the study relied on self-reported data for commuting patterns and physical activity, which may be subject to recall error and social desirability bias. In particular, participants may have overreported active commuting due to social expectations linked to their professional identity as educators and role models. The absence of objective metrics to verify responses (such as GPS data or accelerometers) limits the precision of behavioral assessments.

Third, potential seasonal or academic calendar effects were not accounted for. The data were collected between early 2024 and April 2025, a period that may include fluctuations in commuting behavior due to weather, school breaks, or exam periods. These temporal variables could have influenced participants’ activity patterns but were not controlled for in the study design. Additionally, the scope was limited to public school educators in two major urban centers (Athens and Thessaloniki). Findings may not generalize to rural areas, different professional sectors, or populations with varying socioeconomic or cultural backgrounds. Expanding future research to include diverse geographic and occupational contexts is necessary to draw broader conclusions.

From a methodological standpoint, future studies should incorporate objective measurement tools, such as GPS-tracked commuting routes, wearable activity monitors, or direct observational techniques, to triangulate and validate self-reported behavior. Furthermore, institutional and policy-level factors (for example, availability of bicycle parking, flexible work hours, commuting subsidies) were not examined in this study but may play a critical role in shaping active commuting behavior and warrant closer investigation.

Finally, future research should explore the relationships between commuting behavior and concrete health outcomes, including BMI, metabolic health indicators, and psychological well-being. This is particularly relevant for populations at higher risk of sedentary lifestyles or chronic illness. A deeper understanding of the psychosocial mechanisms, such as motivation, risk perception, and habit formation, will also be essential for designing equitable, context-sensitive, and effective interventions.

Conclusion

This study highlights that active commuting among public school educators in Athens and Thessaloniki is significantly shaped by gender, distance to school, perceived safety, and prior engagement in physical activity. Female participants were less likely to commute actively, particularly when environmental safety concerns were high, while educators who engaged in organized or leisure-time physical activity were more inclined to walk or cycle to work. These findings suggest that addressing psychosocial barriers, particularly among women, should be prioritized alongside infrastructural improvements.

Based on these insights, we recommend targeted urban planning interventions, such as installing protected sidewalks, bike lanes, and improved lighting near school zones. Additionally, public education campaigns and school-based initiatives can help shift cultural norms and perceptions around commuting. At the institutional level, employers should consider providing incentives, like secure bike parking, flexible schedules, and wellness programs, to encourage active transport. Policymakers should also integrate active commuting strategies into broader urban mobility and health promotion frameworks. By tailoring interventions to local barriers and population needs, cities can foster healthier, safer, and more sustainable commuting behaviors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In accordance with ethical research standards, all participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their involvement, and the confidentiality of their responses. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Democritus University of Thrace (Code: ΔΠΘ/ΕΗΔΕ/3825/243; Dated: 19/12/2024). This study was approved by the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs (Protocol Nos.: Φ15/782/126370/Γ1 and 139378/Γ2).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the school principals and public school teachers who participated in the study for their time and valuable input. The authors are also grateful to the regional education authorities in Attica and Thessaloniki for facilitating access to the participating schools.

References

- Aranda-Balboa MJ, Chillón P, Saucedo-Araujo RG, Molina-García J, Huertas-Delgado FJ. Children and parental barriers to active commuting to school: A comparison study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2504. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18052504] [PMID]

- Palma-Leal X, Camiletti-Moirón D, Izquierdo-Gómez R, Rodríguez-Rodríguez F, Chillón P. Environmental vs psychosocial barriers to active commuting to university: Which matters more? Public Health. 2023; 222:85-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2023.06.039] [PMID]

- Rotaris L, Del Missier F, Scorrano M. Comparing children and parental preferences for active commuting to school. A focus on Italian middle-school students. Research in Transportation Economics. 2023; 97:101236. [DOI:10.1016/j.retrec.2022.101236]

- Javadpoor M, Soltani A, Fatehnia L, Soltani N. How the built environment moderates gender gap in active commuting to schools. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1131. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20021131] [PMID]

- Dimoula S, Griva M, Papadaki K. Accessibility in the built and natural environment. Athens: EKDDA; 2023. [Link]

- Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007; 29:129-43. [DOI:10.1093/epirev/mxm009] [PMID]

- Høyer-Kruse J, Schmidt EB, Hansen AF, Pedersen MRL. The interplay between social environment and opportunities for physical activity within the built environment: A scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24(1):2361. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-19733-x] [PMID]

- Ganzar LA, Burford K, Zhang Y, Gressett A, Kohl HW, Hoelscher DM. Association of walking and biking to school policies and active commuting to school in children. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2023; 20(7):648-54. [DOI:10.1123/jpah.2022-0376] [PMID]

- Charisi V, Zafeiroudi A, Trigonis I, Tsartsapakis I, Kouthouris C. The impact of green spaces on workplace creativity: A systematic review of nature-based activities and employee well-being. Sustainability. 2025; 17(2):390. [DOI:10.3390/su17020390]

- Vasilaki M, Zafeiroudi A, Tsartsapakis I, Grivas GV, Chatzipanteli A, Aphamis G, et al. Learning in nature: A systematic review and meta-analysis of outdoor recreation’s role in youth development. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):332. [DOI:10.3390/educsci15030332]

- Ilídio da Silva J, Muraro AP, Cristina de Souza Andrade A. Physical activity of adolescents and the urban environment of Brazilian capitals: National School Health Survey, 2015. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2024; 34(10):3563-74. [DOI:10.1080/09603123.2024.2312425] [PMID]

- Stewart G, Anokye NK, Pokhrel S. Quantifying the contribution of utility cycling to population levels of physical activity: an analysis of the Active People Survey. Journal of Public Health. 2016; 38(4):644–52. [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdv182] [PMID]

- Kerr J, Rosenberg D, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Conway TL. Active commuting to school: Associations with environment and parental concerns. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2006; 38(4):787-94. [DOI:10.1249/01.mss.0000210208.63565.73] [PMID]

- Karakatsanis K, Kipreos G, Mountakis C, Stergioulas A. The commuting profiles of the principals: Their views on the surrounding built environment and infrastructure of their schools and the factors that affect the active commuting of students to and from school. International Journal of Sport Management, Recreation & Tourism. 2015; 17:1-13. [Link]

- Campos-Garzón P, Sevil-Serrano J, García-Hermoso A, Chillón P, Barranco-Ruiz Y. Contribution of active commuting to and from school to device-measured physical activity levels in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2023; 33(11):2110-24. [DOI:10.1111/sms.14450] [PMID]

- Santhosh VA. A study of the impact of workplace commuting on citizenship behaviour of employees working with public and private sector organisations. Vision. 2015; 19(1):13-24. [DOI:10.1177/0972262914564043]

- Petrokofsky C, Davis A. Working together to promote active travel. A briefing document for local authorities. London: Public Health England; 2016. [Link]

- Wang X, Yin C, Shao C. Reexamining the built environment, commuting and life satisfaction: Longitudinal evidence for gendered relationships. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2023; 125:103986. [DOI:10.1016/j.trd.2023.103986]

- Yin C, Zhang J, Shao C, Wang X. Commute and built environment: what matters for subjective well-being in a household context? Transp Policy. 2024; 154:198-206. [DOI:10.1016/j.tranpol.2024.06.011]

- Kaseva K, Lounassalo I, Yang X, Kukko T, Hakonen H, Kulmala J, et al. Associations of active commuting to school in childhood and physical activity in adulthood. Scientific Reports. 2023; 13(1):7642. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-023-33518-z] [PMID]

- Kim EJ, Kim J, Kim H. Does environmental walkability matter? The role of walkable environment in active commuting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(4):1261. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17041261] [PMID]

- Wang Y, Steenbergen B, van der Krabben E, Kooij HJ, Raaphorst K, Hoekman R. The impact of the built environment and social environment on physical activity: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6189. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20126189] [PMID]

- Chica-Olmo J, Rodríguez-Lopez C, Chillon P. Effect of distance from home to school and spatial dependence between homes on mode of commuting to school. Journal of Transport Geography. 2018; 72:1-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.07.013]

- Lozzi G, Monachino MS. Health considerations in active travel policies: A policy analysis at the eu level and of four member countries. Research in Transportation Economics. 2021; 86:101006. [DOI:10.1016/j.retrec.2020.101006]

- Caamaño-Navarrete F, Del-Cuerpo I, Arriagada-Hernández C, Alvarez C, Gaya AR, Reuter CP, et al. Association between active commuting and lifestyle parameters with mental health problems in Chilean children and adolescent. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):554. [DOI:10.3390/bs14070554] [PMID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● International Health

Received: 2025/05/19 | Accepted: 2025/06/25 | Published: 2025/11/1

Received: 2025/05/19 | Accepted: 2025/06/25 | Published: 2025/11/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |