Volume 15, Issue 6 And S7 (Artificial Intelligence 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(6 And S7): 761-778 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

R A, Manoj Kumar D, Lija A V K, Babu P, G V. Simplified Speech Enhancement Using a Wiener Filter-Bi-GRU Hybrid Model. J Research Health 2025; 15 (6) :761-778

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2890-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2890-en.html

1- Department of Electronics &Communication Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram Campus, Chennai, India.

2- Department of Computer Science Engineering, Easwari Engineering College, Anna University, Chennai, India. ,manojkud1@srmist.edu.in

3- Department of Computer Science Engineering, Easwari Engineering College, Anna University, Chennai, India.

2- Department of Computer Science Engineering, Easwari Engineering College, Anna University, Chennai, India. ,

3- Department of Computer Science Engineering, Easwari Engineering College, Anna University, Chennai, India.

Keywords: Speech enhancement, Noise removal, Wiener filter, Bi-GRU, PESQ, STOI, Deep learning (DL), Speech quality enhancement, Medical signal processing, Hearing aids, Telemedicine

Full-Text [PDF 2242 kb]

(177 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2353 Views)

Full-Text: (94 Views)

Introduction

Background noise often distorts and hides speech signals, making them difficult to hear clearly. To address this problem, speech enhancement techniques are used to reduce overlapping noise and make the speech clearer and more natural. The main purpose of a speech enhancement system is to reduce noise in a signal that has been contaminated. It works as a pre-processor for speech recognition systems, making the speech signal cleaner without changing the recognizer itself. These systems are crucial for various applications, including voice-controlled devices, audio restoration, automatic speech recognition, hearing aids, and telecommunications.

The enhancement of distorted speech using additive noise with a single observation has been accomplished; however, it remains a tough issue. Noise is introduced into the pristine speech sample to generate noisy speech with an SNR ranging from 0 to 0.5 dB in increments of 0.01 dB. The proposed model is divided into two phases: (i) Instruction and (ii) evaluation. During the training phase, the noise spectrum and signal spectrum are derived from the noisy input signal using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF). Subsequently, features from the Wiener filter are recovered using empirical mean decomposition (EMD) [1, 2]. This model integrates convolutional encoder-decoder and recurrent architectures to proficiently train intricate mappings from chaotic speech for real-time speech improvement, facilitating low-latency causal processing. Recurrent architectures, including long-short term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent unit (GRU), and simple recurrent unit (SRU), are utilized as bottlenecks to capture temporal dependencies and enhance the performance of speech enhancement. The model utilizes convolutional layers to effectively extract features from raw audio signals, along with layer normalization and bidirectional gated recurrent unit (Bi-GRUs) to capture long-range temporal relationships and contextual information from both preceding and subsequent frames. Substantial enhancements were observed across five training epochs, with the training and validation loss decreasing from 311.9084 to 70.7906 and from 303.5839 to 46.6886, respectively. Speech augmentation techniques have various applications, including hearing aids, voice-controlled devices, cellular phones, automatic speech recognition systems, and multiparty teleconferencing.

There are various methods for filtering the distorted signal. Each approach is distinct, considering numerous criteria and being specific to its application. In certain instances, it may be necessary to enhance speech quality, while in others, accuracy is paramount; achieving both quality and accuracy simultaneously within the same timeframe is challenging [3-5]. However, there are several limitations to spectrogram properties. The resulting signal contains artefacts as a result of the computationally intensive pre- and post-processing steps of the discrete fourier transform (DFT)and its inverse. Second, these techniques often only approximate the magnitude in order to produce the increased speech. Most of the research suggests that the phase can raise speech quality. Adding a specific model for the phase component or anticipating both magnitude and phase may add to model complexity, according to a recent study.

This study aimed to investigate a critical research question stemming from the challenges of speech enhancement in highly non-stationary environments: whether the proposed WRNN exhibits robustness in challenging conditions, such as low SNR levels and fluctuating noise amplitude or variance, in comparison to current state-of-the-art techniques.

Related work

Numerous traditional algorithms play a major role in acting as active noise cancellation (ANC) in speech applications, utilizing adaptive filters, Kalman filters, and Wiener filters. These techniques are widely employed in hearing aids and other edge devices, such as phones and communication devices, while Wiener filtering adapts to industry standards for dynamic signal processing. Contemporary smartphone designers frequently position two microphones at different angles from one another: one close to the speaker’s mouth to record loud speech and the other to assess background noise and filter it out. Signals that have been distorted by noise or other disturbances can be improved or restored using the Wiener filter. It has been extensively utilized in fields, including communications, audio signal improvement, and image processing.

The drawbacks of Wiener filter include the need for separation of audio streams to effectively benefit from it. In scenarios such as a cockpit or smartphone, while having two microphones is useful, it would also be advantageous to handle noise from a single stream. Additionally, when the spectral properties of the audio and the background noise overlap, audible distortions in the speech may occur. The filter’s subtractive design can eliminate speech segments that resemble background noise. These problems have been addressed with the support and development of deep learning (DL) [6].

RNN has never been used for waveform-based speech augmentation; the first application was to denoise a waveform that was not speech, and the second was to increase speech bandwidth. The high resolution of waveforms calls for networks that are broader, deeper, and more expensive. Building a deep RNN is difficult because saturated activation functions cause gradient degradation over layers. Furthermore, our research indicates that the size of the RNNs required for analyzing high-resolution waveforms demands larger RAM [7]. This systematic review analyzed speech improvement and recognition methodologies, focusing on denoising, acoustic modeling, and beamforming. An overview of various DL architectures, including deep neural networks (DNN), convolutional neural networks (CNN), recurrent neural networks (RNN), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and hybrid neural networks, emphasizes their contributions to enhancement and recognition [8]. It introduces UniInterNet, a unidirectional information interaction-based dual-branch network designed to facilitate noise modeling-assisted software engineering without increasing complexity. The noise branch still receives input from the speech branch to enhance the accuracy of noise modeling. The findings from noise modeling are then utilized to aid the speech branch during backpropagation. This research presents a complete framework for speech emotion recognition that integrates the ZCR, RMS, and MFCC feature sets.

Our methodology utilized both CNN and LSTM networks, augmented by an attention model, to improve emotion prediction. The LSTM model specifically tackles the issues of long-term dependency, allowing the system to include prior emotional experiences in conjunction with present ones [9, 10]. The Wiener filter is used to process the noisy speech signals and produce the clean speech targets. The RNN is then trained to use for minimizing mean squared error (MSE) or perceptual loss functions to decrease the difference between the target clean speech spectrum and the anticipated enhanced speech spectrum. The advantages of both strategies can be leveraged when the Wiener filter and RNN are used together compared to leading-edge techniques such as RNN-IRM [11], RNN-TCS [12], and RNN-ARN [13]. Studies have shown that advanced recurrent networks (ARN) perform better than other methods, like RNNs and dual-path ARNs, for improving speech in the time domain. Many contemporary smartphones are equipped with two closely positioned microphones. One microphone is positioned near the speaker’s lips to capture loud speech, while the other detects background noise and filters it out [14, 15]. For sparse noise, which is mostly very low frequency with high decibels, there is a chance that it may lead to noise-induced hearing loss, necessitating the use of a hybrid algorithm to control its occurrence [16].

In speech improvement tasks, the bi-GRU model is frequently employed to improve the quality of voice signals by lowering background noise. It utilizes the model’s bidirectionality to gather information from the input sequence’s past and future frames. The bi-GRU model is used in speech enhancement to process noisy speech signals in both forward and backward directions at the same time. This approach helps capture long-term dependencies and improves voice quality by enabling the model to learn representations that combine data from both previous and subsequent time steps.

Upon analyzing this approach, it was found that a deep structured network finds it difficult to appropriately estimate the infinte dynamic range of the SNR (−∞, ∞). For this reason, a compression function was used to prevent the convergence issues [17]. Moreover, SNR serves as a transitional stage before acquiring the Wiener filter function, which is needed to feed the SE algorithm. Therefore, the network’s ability to produce a more reliable estimate of the Wiener filter through direct learning is more practical.

The optimal use of the network for learning a robust instance of the Wiener filter estimator is found based on the properties of the speech enhancement algorithm’s intermediate phases, namely the SNR estimation and the gain function [18-22]. This work presented a novel DL model for sentiment analysis utilizing the IMDB movie reviews dataset. This model executes sentiment classification on vectorized reviews employing two Word2Vec methodologies, specifically Skip Gram and Continuous Bag of Words, over three distinct vector sizes (100, 200, 300), utilizing 6 bi-GRU and 2 convolutional layers (MBi-GRUMCONV). In the trials utilizing the suggested model, the dataset was divided into 80%-20% and 70-30% training-test sets, with 10% of the training subsets allocated for validation purposes.

Furthermore, it introduces a time-domain multi-channel Wiener filter algorithm for enhancing speech in the distributed speech model, aimed at recovering pure speech from observed speech. This paper initially presents the formula for the energy associated with noise reduction and speech distortion, subsequently formulates the optimization problem concerning these factors, and ultimately resolves the optimization problem to derive the formula for the optimal linear filter. This work employs an iterative technique to estimate the autocorrelation matrix of the source speech signal, thereby enhancing estimation accuracy. The findings of the simulation experiment indicate that the suggested approach outperforms numerous traditional multi-channel speech enhancement algorithms.

The problems identified in the traditional algorithm have motivated the proposal of a design for a reliable automatic signal detection and recognition system, which focuses on amplifying weak signals in the presence of channel noise and background interference. The distinguishing features, like SNR estimation and gain of input source waveforms or their spectra, can be mapped using the auto-associative property of the Wiener filter.

The novelty of the proposed work lies in utilizing the capabilities of Bi-GRU-based neural networks to create filters that first learn and then subtract background noise from the input waveform, thereby increasing the likelihood of detecting weak signals. Practical challenges in enhancing non-stationary and non-causal signals can be effectively addressed by a WRNN that learns to selectively filter out background noise without significantly affecting the signal.. Furthermore, using different corpora with non-stationary noises under low SNR conditions, in the presence of background noise and channel noise, a novel base WRNN filter improves signal detectability based on an analytical foundation.

Section 2 will explain the signal model and problem formulation. This section includes a block diagram, as well as discussions on pre-processing, noise removal, and post-processing. Section 3 will discusse the simulation results and provide a discussion on existing and proposed techniques, followed by conclusions.

Methods

Signal model and problem formulation

Noise can easily mixed with speech signals in real-world settings. Reverberations fall into two categories: stationary noise (which does not change over time) and non-stationary noise (which changes when shifted in time). Examples of background noise in the non-stationary category include street noise, babble noise, train noise, cafeteria noise (from other speakers’ voices), and instrumental sounds.

Block diagram of the proposed work

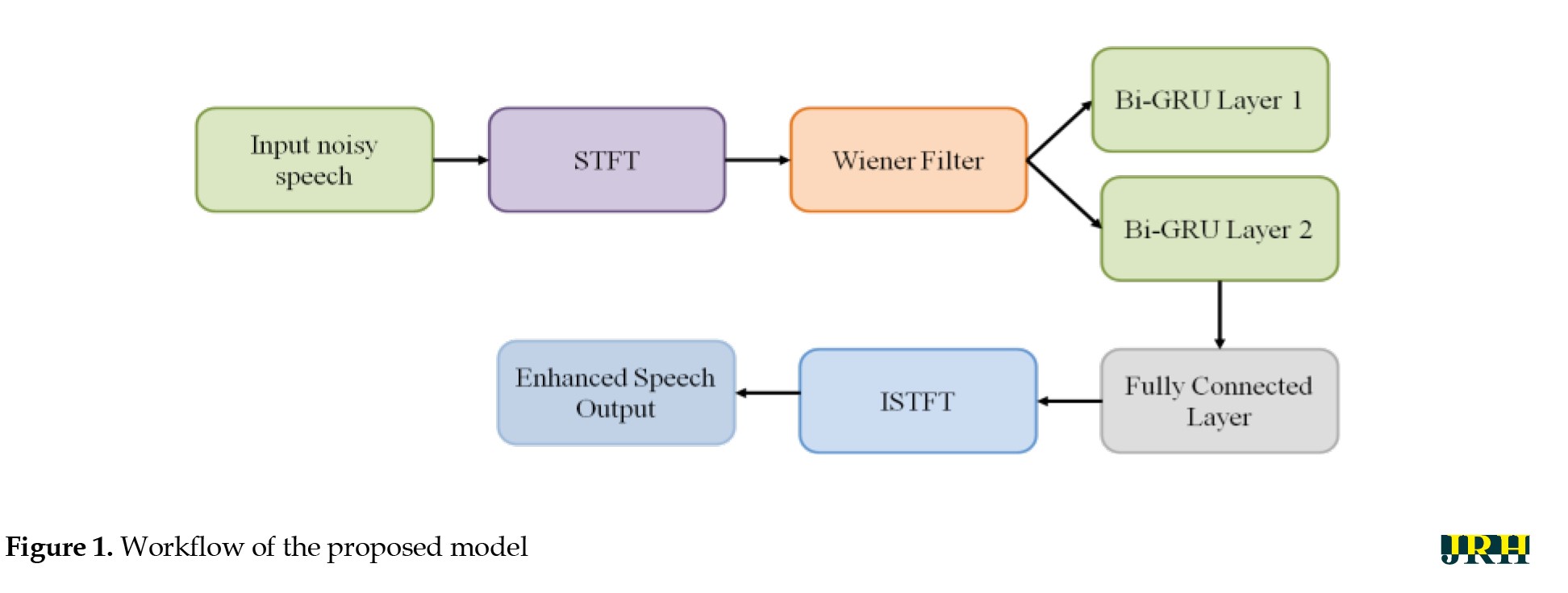

The proposed WRNN Model consists of three stages, namely pre-processing, noise reduction, and speech enhancement in post-processing, as shown in Figure 1.

Noisy speech input

A noisy speech signal—which includes both speech and undesired background noise—is used to initiate the procedure. The system’s objective is to improve voice quality by lowering noise levels.

Short-time fourier transform (STFT)

STFT is used to transform the time-domain loud speech into the time-frequency domain. To examine frequency components over time, STFT splits the signal into tiny frames and uses the Fourier transform. This facilitates the separation of speech and noise components.

Wiener filter

The Wiener filter is a traditional technique for reducing noise. It operates by minimizing the mean square error between the real and estimated clean signals. This block creates a spectrogram with reduced noise and provides initial noise suppression.

Bi-GRU layers (layers 1 & 2)

Following Wiener filtering, the features are fed into sophisticated RNN called Bi-GRU. In order to improve speech feature representation, Bi-GRU layers 1 and 2 progressively process information from both past and future contexts. This improves the ability to distinguish speech from noise and aids in modeling temporal connections.

Fully connected layer

A completely connected layer receives the processed features from the Bi-GRU layers. This layer maps the high-level learned features into the necessary format (e.g. predicted clean speech magnitude spectrogram). Essentially, it serves as a decision-making stage to complete the enhancement.

Inverse short-time fourier transform (ISTFT )

ISTFT is used to transform the improved spectrogram back into the time-domain waveform. The improved voice signal is reconstructed in this manner.

Enhanced speech output

The outcome is a clearer speech signal with diminished background noise and enhanced intelligibility.

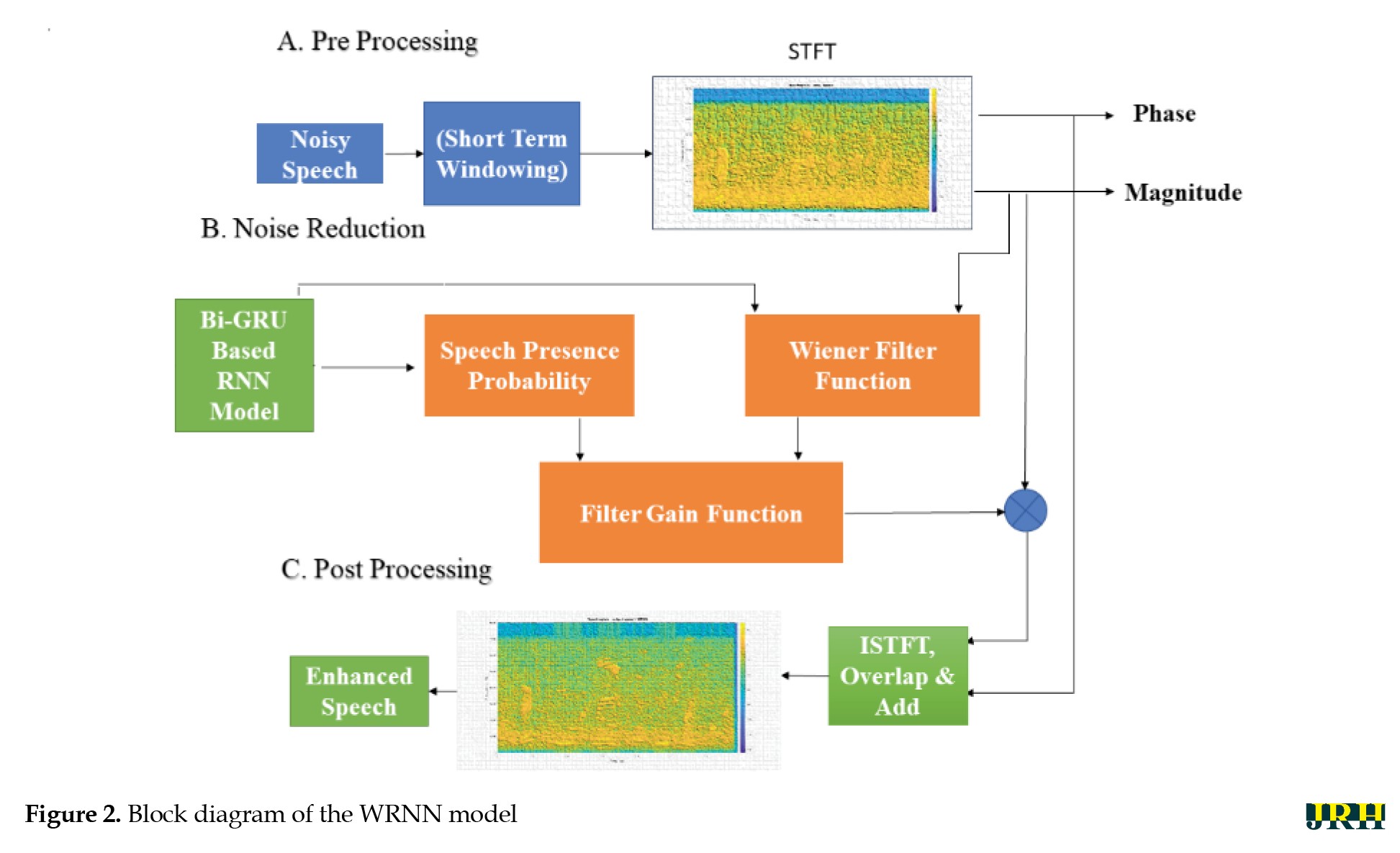

Figure 2 depicts the proposed block diagram for speech enhancement with background non-sationary noise reduction. In a pre-processing stage, initially noisy data will undergo short-term windowing techniques, and this output will be applied to the STFT to obtain the phase and magnitude response. In second stage, which is the noise reduction stage, the Wiener filter function is used to calculate the gain factor and SNR estimation for the input features before moving to the post-processing stage. In the third stage, ISTFT is initially applied using an overlap-add convolution method to extract input features for the Bi-GRU-based RNN model, which is designed to remove non-stationary noise components from noisy speech. The detailed stage-wise explanation follows in the next section.

Pre-processing and database

To develop an accurate noise removal model, creating a high-quality training dataset is crucial. In this case, the TIMIT and WSJ databases were used to obtain clean speech and noisy speech data. These two databases were combined to create a larger dataset comprising a total of 7.5 hours of speech. The dataset was then split into separate portions: 60% for training, 20% for development, and 20% for testing.

During the construction of the dataset, certain considerations were taken into account. Firstly, the ratio of male to female speakers was balanced to ensure a diverse representation of voices. Additionally, it was ensured that there is no overlap of speakers between the different groups. This helps maintain the independence of the data subsets and prevents any bias that could arise from having the same speaker present in multiple sets.

The inclusion of both clean speech and its corresponding noisy counterpart in the dataset is essential because the objective is to reduce background noise. The nature of the dataset should align with the specific use case of the model being developed. For instance, if the model is intended to be used for noise removal in signals from a helicopter pilot’s microphone, it would be logical to train the network using auditory samples corrupted by rotor noise.

On the other hand, for a noise removal model intended for widespread use, incorporating authentic background noises, such as air conditioning, typing, dog barking, traffic, music, and loud conversations would be reasonable. The optimum way to use the network for learning a reliable Wiener filter estimator is defined by the properties of the speech enhancement algorithm’s intermediate phases, namely the gain function and SNR calculation. Studies demonstrate that the robustness of the statistical-based speech estimator technique stems from the data-driven learning process of the SNR estimator, resulting in high performance.

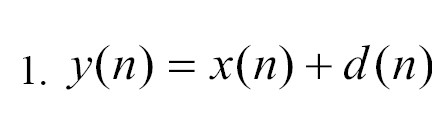

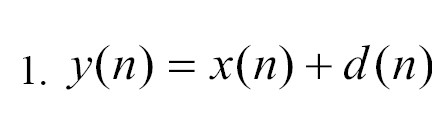

In the Equation 1:

where “x(n)” represents clear speech, “d(n)” stands for additive noise, and “n” represents the discrete-time index, the observed noisy speech signal is denoted as “y(n)”. To begin the pre-processing stage for speech enhancement in the spectral domain, the observed noisy speech signal “y(n)” is segmented into overlapping frames using a window function. This segmentation facilitates the analysis of the speech signal over shorter time intervals and captures the temporal characteristics of the signal. Following the segmentation, a STFT is applied to each frame. The STFT computes the spectrum representation of the signal by taking the Fourier transform of each frame. This transformation converts the speech signal from the time domain to the frequency domain, providing information about the spectral content of the signal at different frequencies. The STFT representation of the segmented frames can be represented as a matrix, where each column represents the frequency content of a specific frame. This matrix can be further processed using various speech enhancement techniques to decrease or eliminate the noise component and improve the excellence of the speech signal.

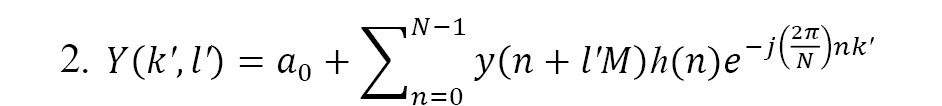

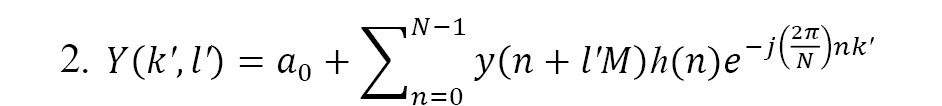

In the spectral-domain speech estimator method, as shown in Equation 2, various steps are involved. The equation includes the time frame index l’, the analytical window size y(n), and the number of samples between two frames denoted as Nand M. The input for the noise reduction block is the power spectrum, represented as , where l′ is the time frame index and k′ is the frequency frame index. The spectral phase is separated in the last post-processing step to facilitate voice reconstruction. The output of the system is an enhanced version of the noisy signal that closely resembles clear speech to the extent possible. The central block in the figure represents the core component of the enhancement technique. This concept is shared by the family of spectral-domain speech estimator methods.

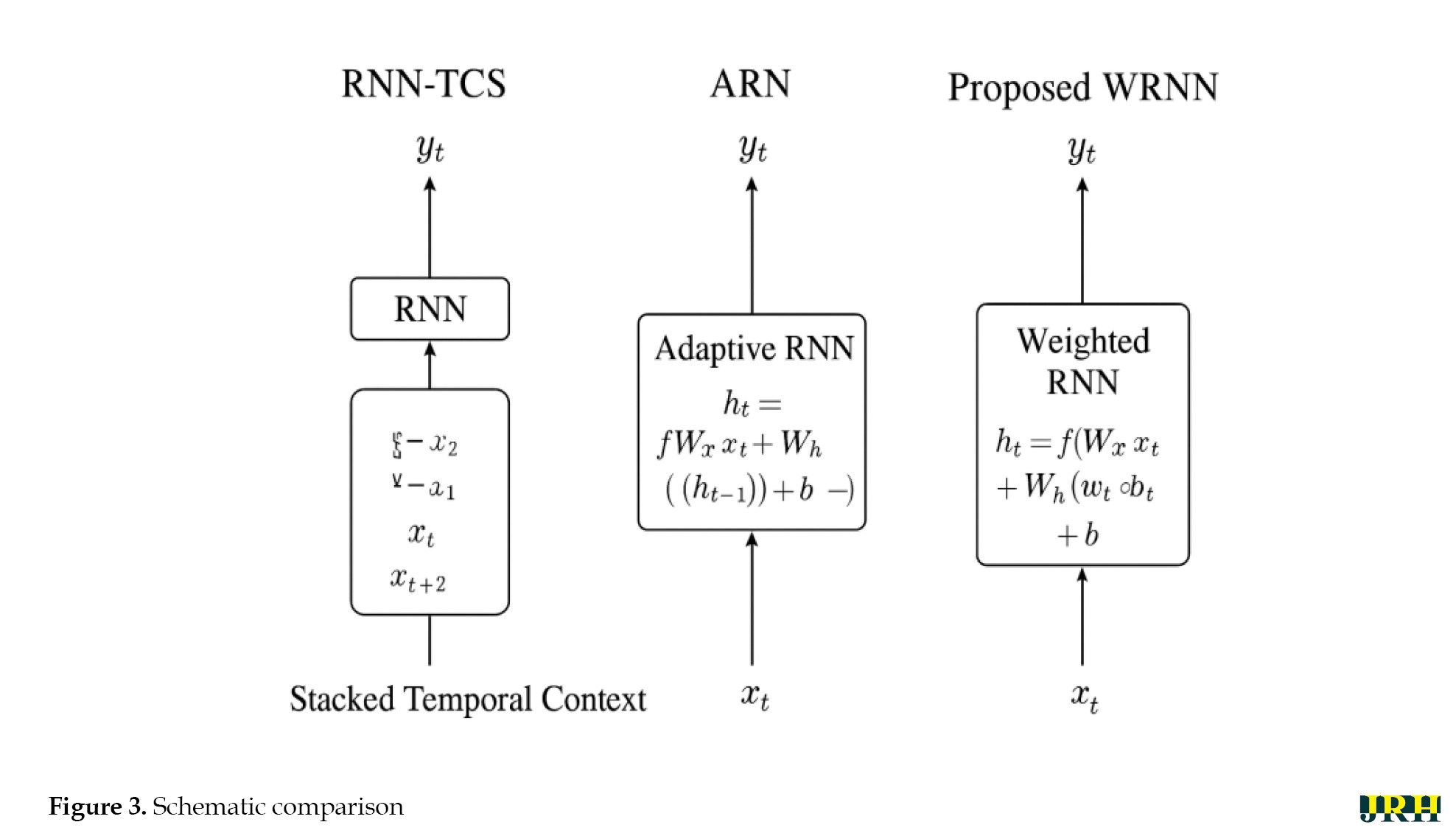

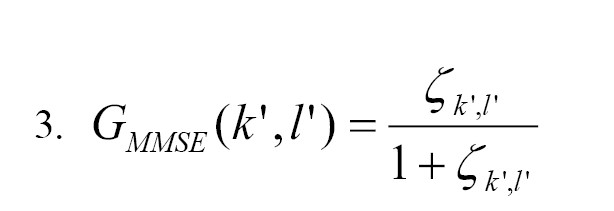

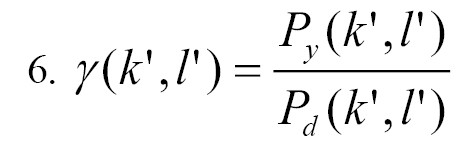

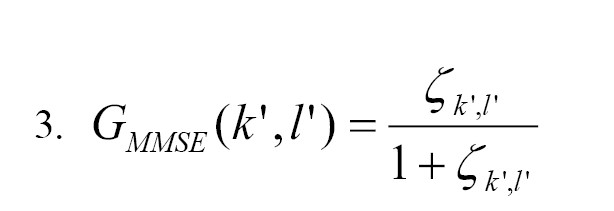

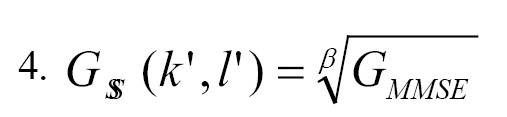

However, it is important to note that in this particular instance, both the presence and absence of speech are considered separately. The filter gain function that modifies the power spectrum, denoted as , is determined using the gain of the minimum mean square error (MMSE) estimator, known as GMMSE. The GMMSE gain is based on the likelihood that speech is present in the signal. The spectral-domain speech estimation method calculates the filter gain function using various factors and techniques as Shown in Figure 3.

Noise simulation

To examine the effects of both variance and amplitude changes in background noise, controlled noise simulation was carried out in addition to using normal clean and noisy datasets. Gaussian and babbling noise samples with different noise strength levels were created for this purpose. A range of SNR circumstances (−5 dB, −2 dB, 0 dB, and +5 dB) were simulated by scaling the magnitude of the noise components. Likewise, variance scaling was used to simulate time-varying noise energy fluctuations. This provided us with the opportunity to investigate how the WRNN responds to abrupt and arbitrary variations in noise levels.

Noise reduction stage (wiener filter)

Wiener filtering is widely used as a standard dynamic signal processing technique in hearing aids and other auxiliary devices, like phones and communication equipment. It is an adaptive filter that performs optimally when provided with two audio signals - one containing both speech and background noise, and the other measuring only the background noise. Modern smartphones often incorporate two microphones placed at a distance from each other. One microphone is positioned near the speaker’s lips to capture the speech, which may be accompanied by noise, while the other microphone is dedicated to monitoring the background noise, enabling effective noise filtering.

Because it can anticipate and reduce noise, the Wiener filter is essential for both noise removal and augmentation. There are difficulties when integrating Wiener filters into big communication systems, including hardware needs and power consumption. The performance of the system was improved by employing the pipelined method. The proposed Wiener filter addressed iteration issues encountered in traditional designs by replacing the division operation with an effective inverse and multiplication operation. The architecture for matrix inversion was also redesigned to reduce computational complexity. Consequently, we directly expressed the Wiener filter’s gain function as Equation 3:

Where is the computed a priori SNR for each frequency k bin and time slice l.

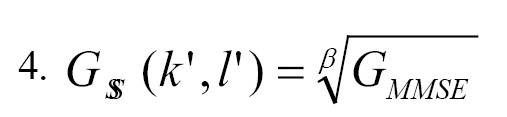

For each variance of a spectral component, the gain function in the SS approach is, for example, defined as the square root of the maximum likelihood estimator. This can be explained by GMMSE as (β = 2) (Equation 4):

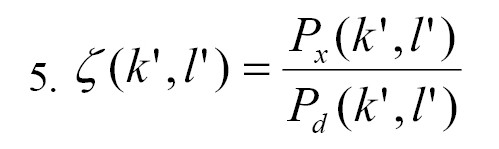

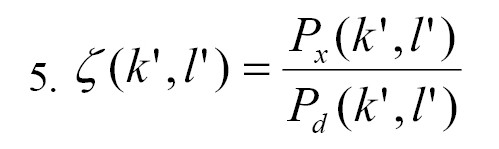

Regarding changes to this algorithm, several modifications have been researched. The a priori and a posteriori SNR are widely used to describe traditional speech enhancement algorithms. The a priori SNR is calculated using the PSD of the noise signal and the clean speech (Equation 5):

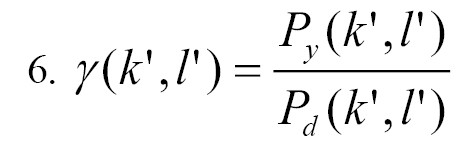

Where represents the clean speech PSD, refers to is the noise signal PSD, both in frequency bin k. The noise signal PSD and the noisy spectral power determine the a posteriori SNR (Equation 6).

As we can see, the a posteriori SNR may be derived utilizing the noisy spectral power along with an estimate of the PSD of the noise. To determine the noise spectrum, numerous statistical algorithms have been proposed. For instance, minima controlled recursive averaging (MCRA), minimal statistics, and histogram-based techniques, among others. Artificial neural networks, once a novel idea, have recently gained traction as DL. Despite the existence of various DL techniques for noise removal, they all operate by learning from training samples. Within the framework of the traditional spectral-domain speech estimator algorithm, the proposed work suggests a Wiener filter estimator for voice augmentation based on DL. The optimal use of the network for learning a robust version of the Wiener filter estimator is determined by the properties of the intermediate phases of the speech enhancement algorithm, namely SNR estimation and the gain function. Experiments demonstrate that employing data-driven learning of the SNR estimator yields state-of-the-art performance and provides resilience to the statistically-based voice estimator technique.

Post-processing (speech enhancement)

The post-processing stage proposes a solution to address the challenges by combining a GRU with learned speech features along with an adaptive Wiener filter. The main contributions of the proposed work can be summarized as follows:

(i) Modified wiener filter: The proposed work designs a modified version of the Wiener filter for decomposing the speech spectral signal to enhance the performance of speech by effectively separating the speech and noise components.

(ii) Introduction of Bi-GRU model: The Bi-GRU model is introduced to accurately estimate the tuning factor of the Wiener filter for each input signal. As a type of RNN, the Bi-GRU is capable of learning and capturing the temporal dependencies of the speech signal, which helps in determining the appropriate tuning factor for noise reduction.

(iii) Training with extracted features: The modified Wiener filter is used to train the GRU model by utilizing the extracted features obtained from the trial phase of the process called empirical mode decomposition (EMD). EMD captures relevant information about the speech and noise components that are used as input for the Bi-GRU model during the training phase. By combining the modified Wiener filter, the Bi-GRU model, and the extracted features from EMD, the proposed work aims to strengthen the accuracy and effectiveness of speech enhancement by dynamically adapting the Wiener filter based on the input signal characteristics.

For the voice augmentation challenge, advancements in DL have achieved excellent results, demonstrating the removal of background noise, including dog barking, kitchen noise, music, babbling, traffic, and outdoor sounds. The novelty of the proposed work lies in its effectiveness in attenuating both quasi-stationary and non-stationary noise compared to conventional statistical signal processing methods.

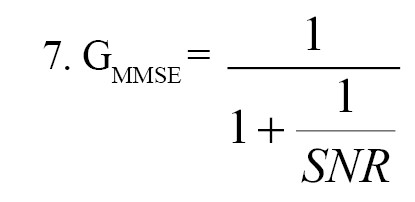

When the measured signal is minimally influenced by noise or is predominantly clean, the dynamic range of the SNR may increase due to the potential values used as outcomes, making regression more susceptible to errors in this situation. However, due to the influence of SNR on the GMMSE (Equation 7), high SNR conditions produce substantial gain values with GMMSE approaching 1, while low SNR conditions result in GMMSE approaching 0. As a result, the dynamic range needed to achieve regression for the GMMSE would be bounded between [0, 1], making it a task that a deep structured network is better equipped to perform.

Another factor that contributed to the choice of a deep structured network for this purpose was its ability to create a causal augmentation system. This implies that it can be utilized in online applications since it is not dependent on future time frames. The network also employs non-recursive estimating techniques to prevent the propagation of estimation errors from earlier frames. The previously stated statistical SNR-estimators often rely on recursive (feedback system) and causal algorithms.

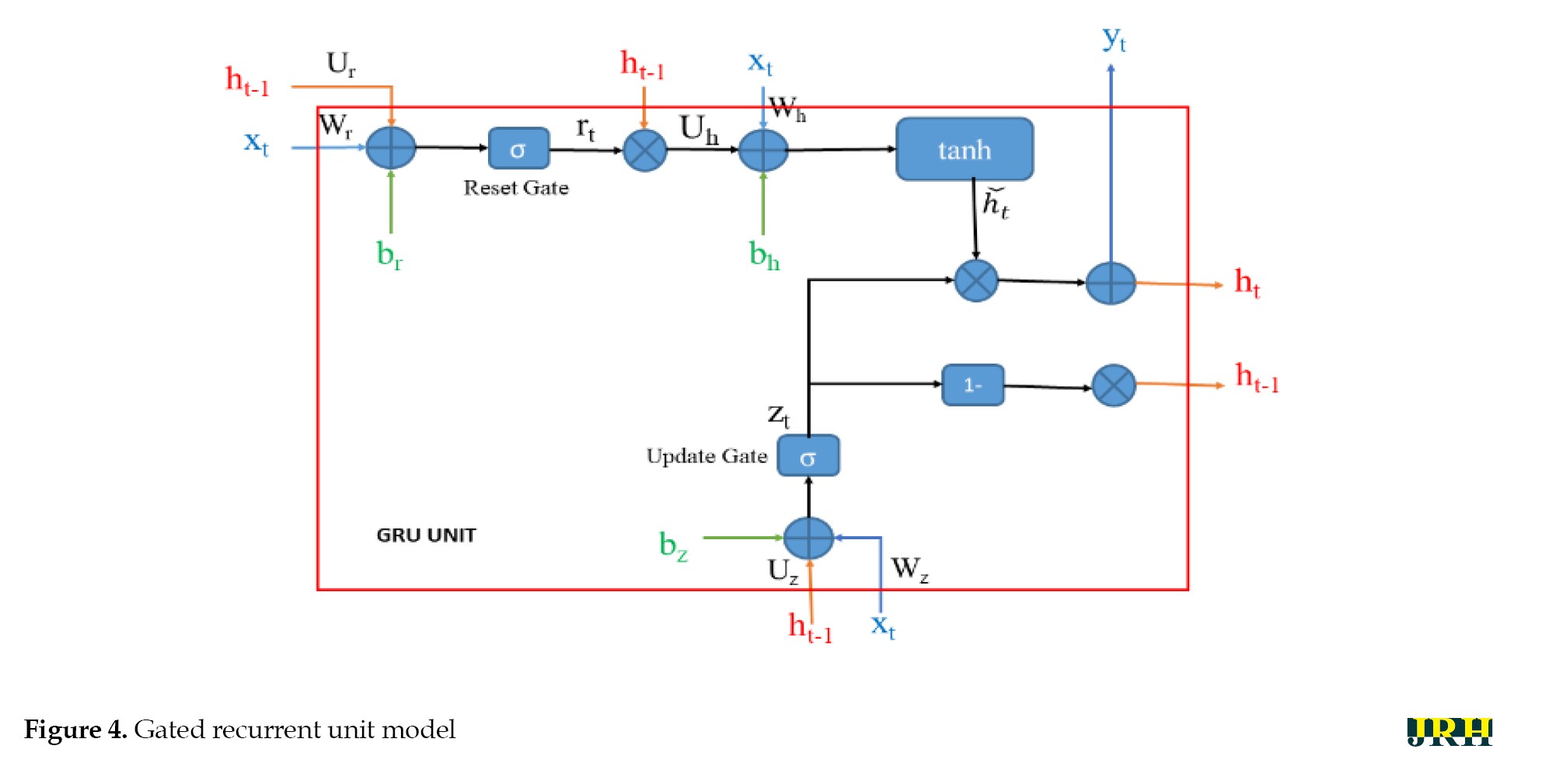

The suggested RNN-based noise reduction technique is illustrated in Figure 4. The deep structured network was trained in a supervised manner using both noisy audio samples and clean audio samples as inputs. The objective of the network was to accurately predict the MMSE gain from the noisy signal based on Equations 2 and 4. To achieve this, the network needs to be aware of the power spectral density (PSD) of the noise, denoted as , and the PSD of the clean speech, denoted as , during the training process. These PSDs are estimated using the Welch approach, which is a commonly used method for PSD estimation.

Bi-GRU model

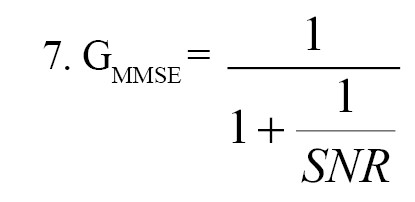

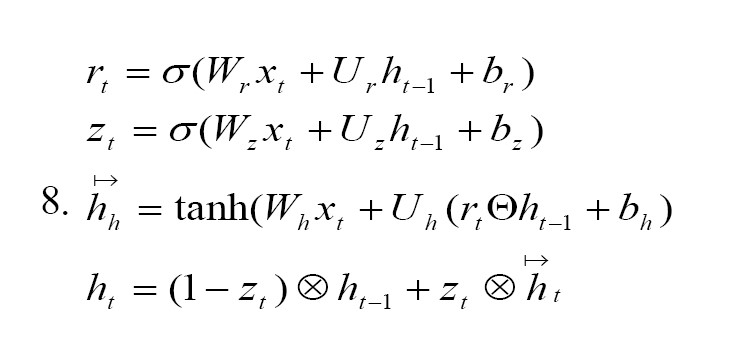

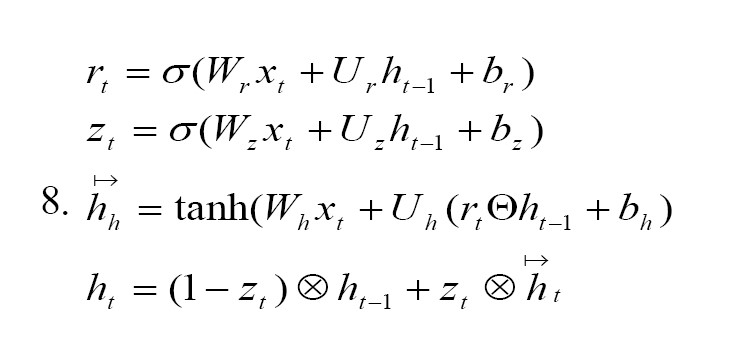

RNNs are capable of handling sequential data. As they work with the current data, RNNs can also retain knowledge from earlier data. The GRU is a less complex version of the GRU, both of which are enhanced RNN models with potent modelling skills for long-term dependencies [20]. A reset gate and an update gate make up a GRU unit. Under the direction of these two gates, the output ht is governed by both the present input and the preceding state h(t−1). The outputs of the gates and the GRU unit are calculated using Equation 8.

Where Wr,Ur,Wz,Uz,Wh, and Uh are the weight matrices, and br,bz, and bh are the bias vectors. Equation 7 represents the equations used in the GRU model, where xt is the input at time step t, ht−1 is the previous hidden state, and rt,zt, and ht are the update gate, reset gate, and current hidden state, respectively, at time step t. The update gate rt controls how much of the previous hidden state should be considered for the current time step, while the reset gate zt determines how much of the previous hidden state should be ignored. These gates are computed using the logistic sigmoid function σ. The hidden state ht is computed based on the input , the previous hidden state ht−1 and the update and reset gates. The Hadamard product, , is used to combine the input and the previous hidden state with the update gate, and the hyperbolic tangent function (tanh) is applied to obtain the current hidden state.

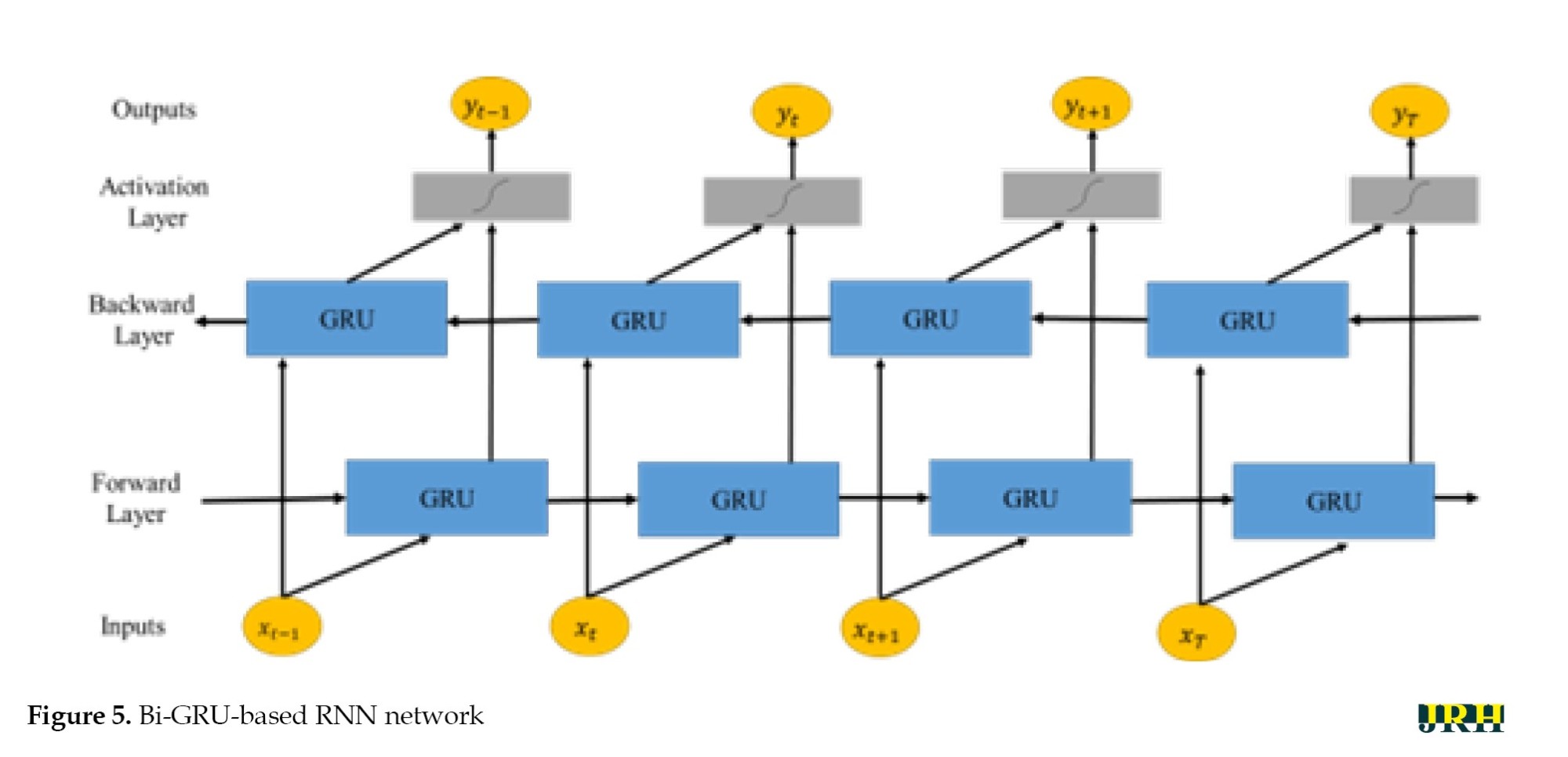

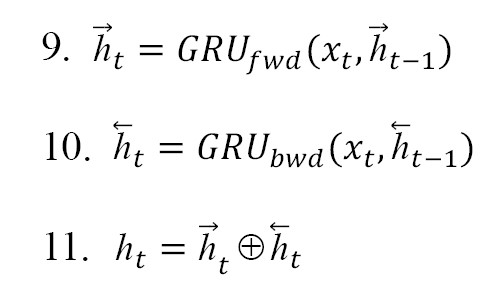

When working with sequential data, models with a bi-directional structure have the capability to learn information from both past and future data points. Figure 5 illustrates the structure of the bi-GRU model. It consists of two GRUs, one moving forward and the other moving backward. The first GRU processes the input sequence from the beginning to the end, capturing the dependencies in the forward direction. The second GRU processes the input sequence in reverse, starting from the end and moving toward the beginning, capturing the dependencies in backward direction [21]. By combining the outputs of the forward and backward GRUs, the bi-GRU model incorporates information from both past and future contexts, allowing it to have a more comprehensive understanding of the input sequence at each time step.

In Equation 9, is represented by the state of the forward GRU, similarly Equation 10, is reprsented by the state of the backward GRU and Equation 11 is represented by overall i.e Bi-diectional GRU states and indicates the operation of concatenating two vectors. In the Equations 9, 10 and 11, GRUfwd represents the hidden state of the forward GRU at time step t, GRUbwd represents the hidden state of the backward GRU at time step t, and xt is the input at time step t. Additionally, and represent the hidden states of the forward and backward GRUs from the previous and subsequent time steps, respectively. The output of the bi-GRU at each time step, ht, is a concatenation of the forward and backward hidden states, providing a richer representation that incorporates information from both directions.

The GMMSE was calculated using a GRU-based RNN design with multiple inputs based on 1-dimensional convolutions. The MATLAB tool was utilized to generate the patterns. The front end of the system employed a set of speech representations computed on a 25 ms Hamming window frame with a 10 ms overlap.

This included calculating a 512-dimensional FFT, 32 Mel filter banks, and 32 cepstral features. These features were then stacked to create a single input feature vector for the network for each frame slice. To normalize the input data, the mean and variance of the training samples were used. During the training process, input features were generated on the fly, which allowed the system to compute mask predictions for each time-frequency area in a single forward pass while calculating the average loss to determine the gradients. For training the network, each audio file in the training set was divided into two-second segments, equivalent to 200 frames. A batch of 32 of these segments was then used to train the network. During the evaluation phase, the mask inference was computed for each speech in the evaluation group.

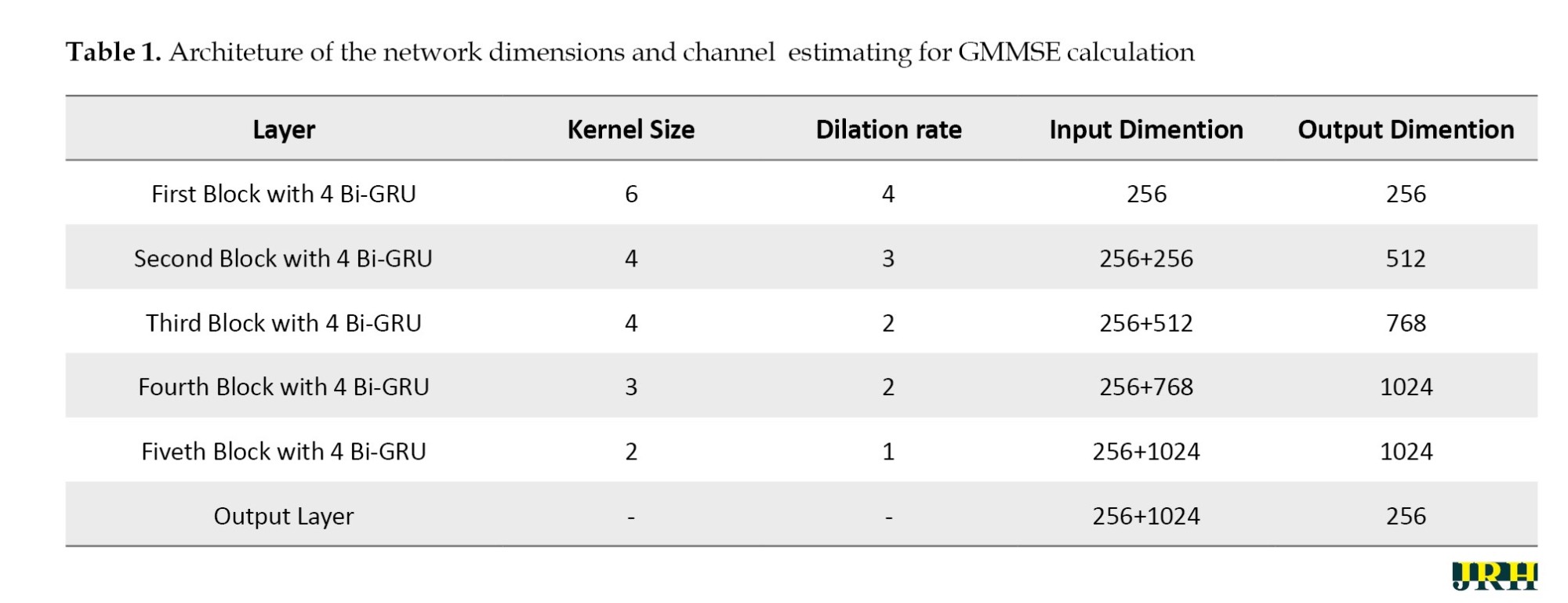

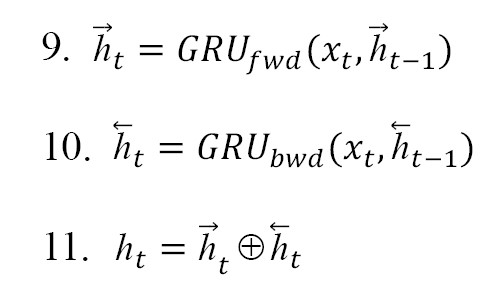

To train a deep neural network, a 1-D CNN was employed to classify the sequence data and learn its features by applying sliding convolutional filters to the 1-D input. Because convolutional layers can process the input in a single operation, employing 1-D convolutional layers can potentially be faster than utilizing recurrent layers. Recurrent layers, on the other hand, have to repeat across the input’s time steps. The normalized molecular property of the sequence data was then extracted using a 1D CNN. Moreover, temporal characteristics were retrieved from the extracted data using GRU layers. The system’s design comprised five Bi-GRU blocks, each with an increasing number of channels. The specific details of the network dimensions of the architecture used for estimating GMMSE are provided in Table 1.

Applications of WRNN in medical signal enhancement

The suggested WRNN model had significant potential for processing medical signals, particularly for eliminating noise in biomedical acoustic signals such as phonocardiograms and respiratory sounds. In telemedicine and assistive hearing applications, environmental and physiological noise can obscure clinically significant characteristics. By effectively removing non-stationary noise components, the hybrid WRNN framework can enhance these signals, making automated analysis systems more reliable for diagnosis. Furthermore, the proposed model’s ability to maintain speech clarity while reducing distortion is highly beneficial for real-time monitoring and communication with patients in speech-based pathological assessments and hearing aids.

Results

Simulation results

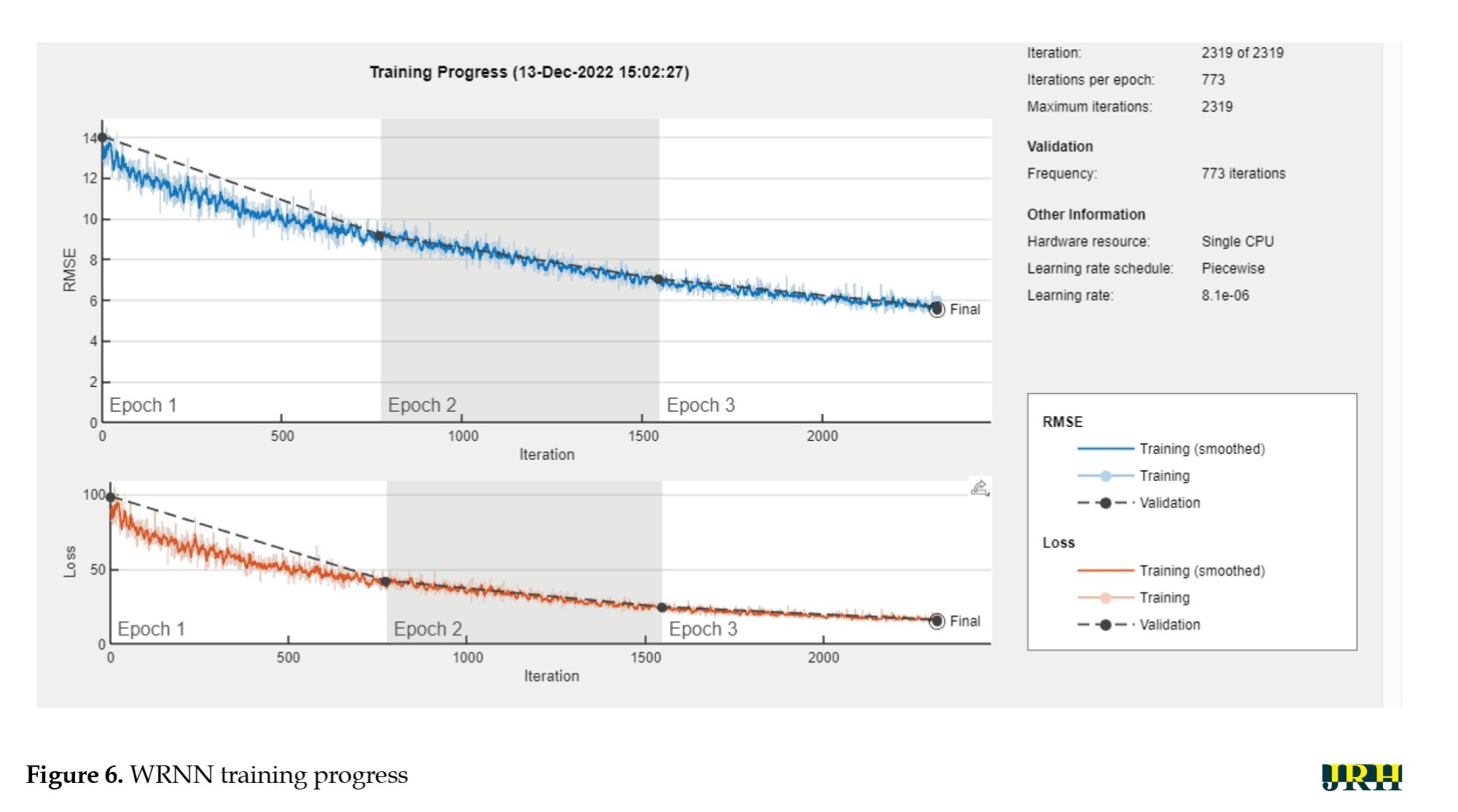

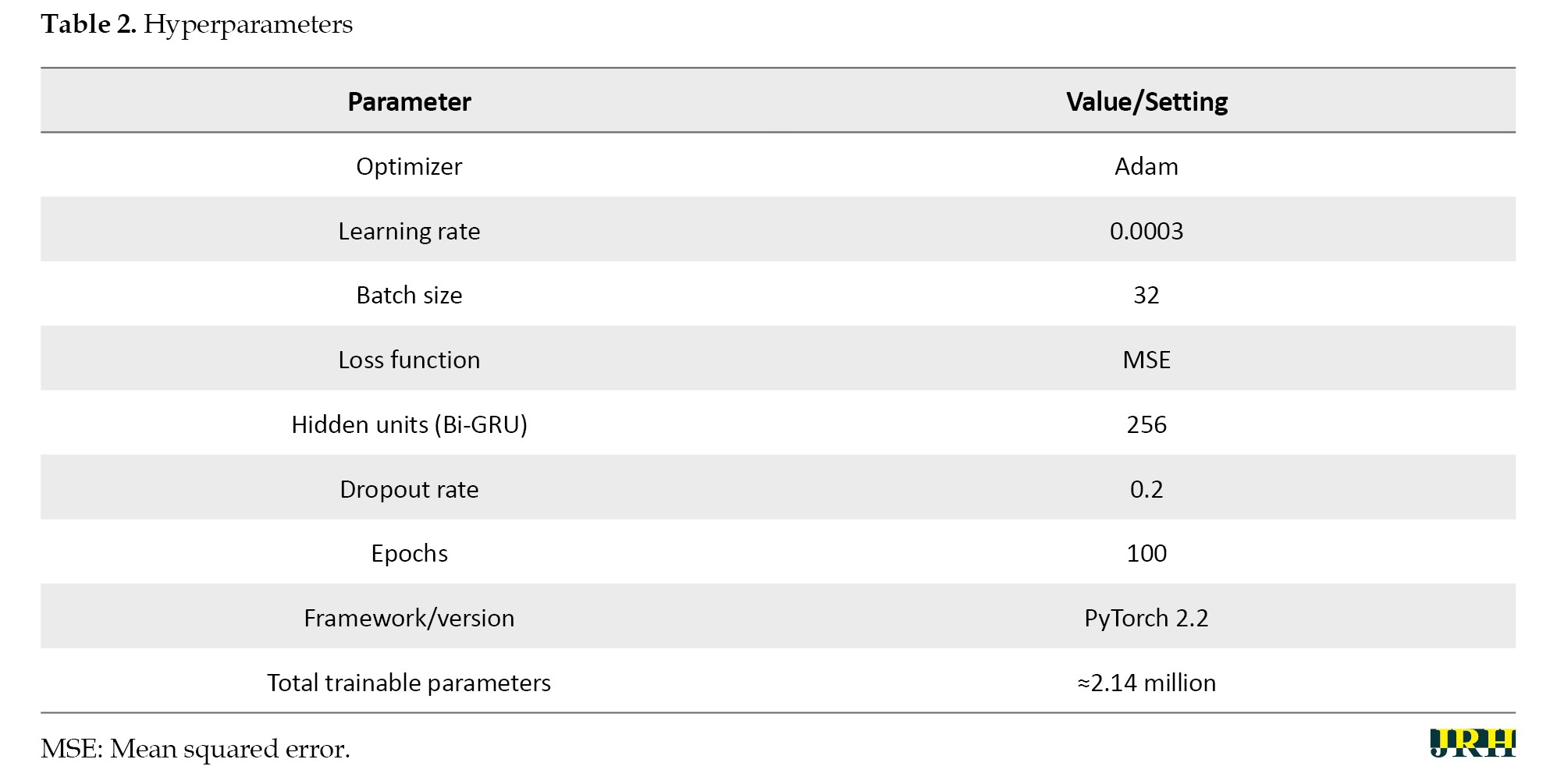

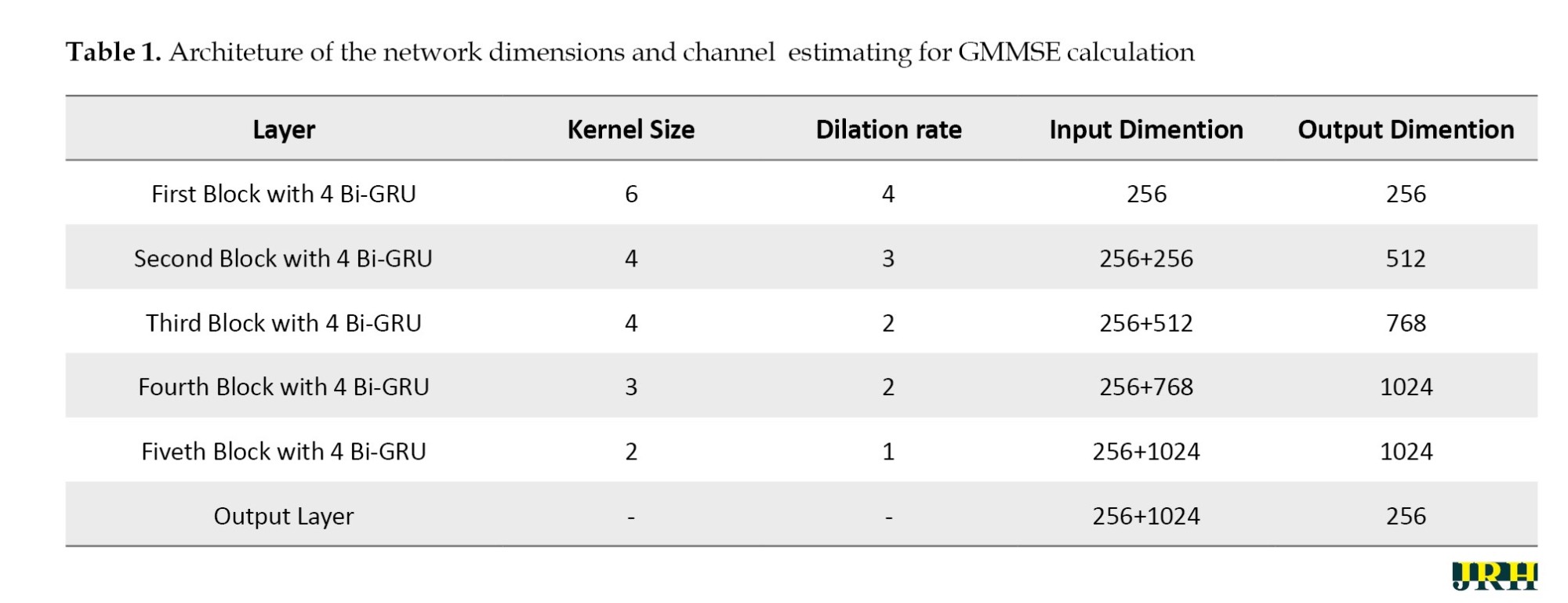

Figure 6 shows the training progress response for the WRNN model. Table 2 provides the hyperparameters and settings for the proposed model.

The maximum number of iterations for the training session was 2,319, with 3 epochs observed and 773 iterations per epoch. The first response represents iteration versus RMSE, while the second represents iteration versus loss. During the training process, epoch 1 showed a significant difference in RMSE and loss, while epoch 2 showed a decaying trend with stability in epoch 3, reaching minimal RMSE with zero loss in both the training and validation processes at the final stage.

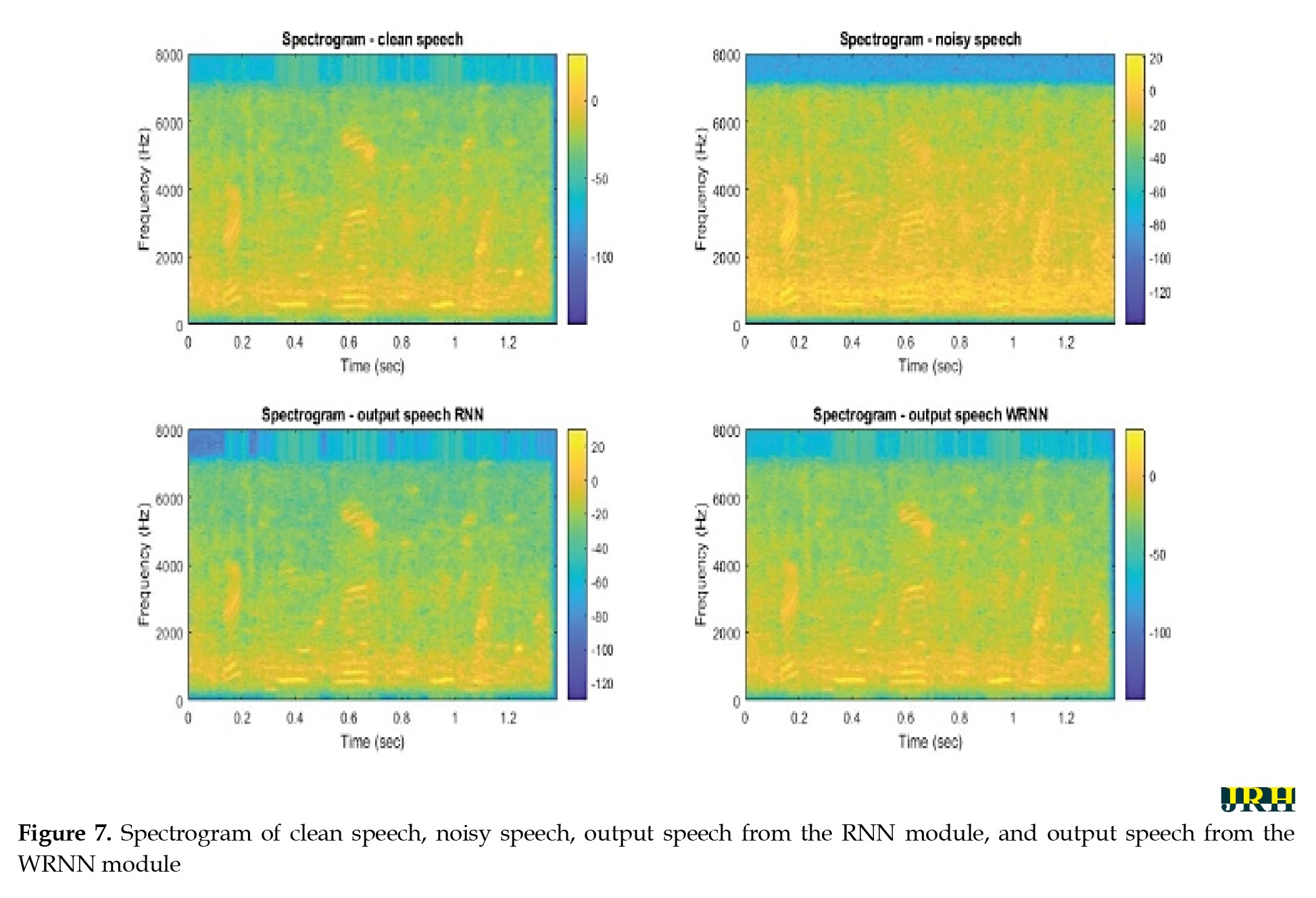

The speech data was chosen randomly from the test set, and both the suggested and current techniques were used to assess the background noise of babble noise with SNR values of -5 dB & -2 dB. Figure 7 displays voice spectrograms before and after WRNN-based speech improvement processing. There were four subplots, namely clear speech, noisy speech, normal RNN, and WRNN. In contrast to the RNN module, the residual noise components of the WRNNs were nearly equal to the original clear speech, while the improved speech spectra were blurred along both the time and frequency axes.

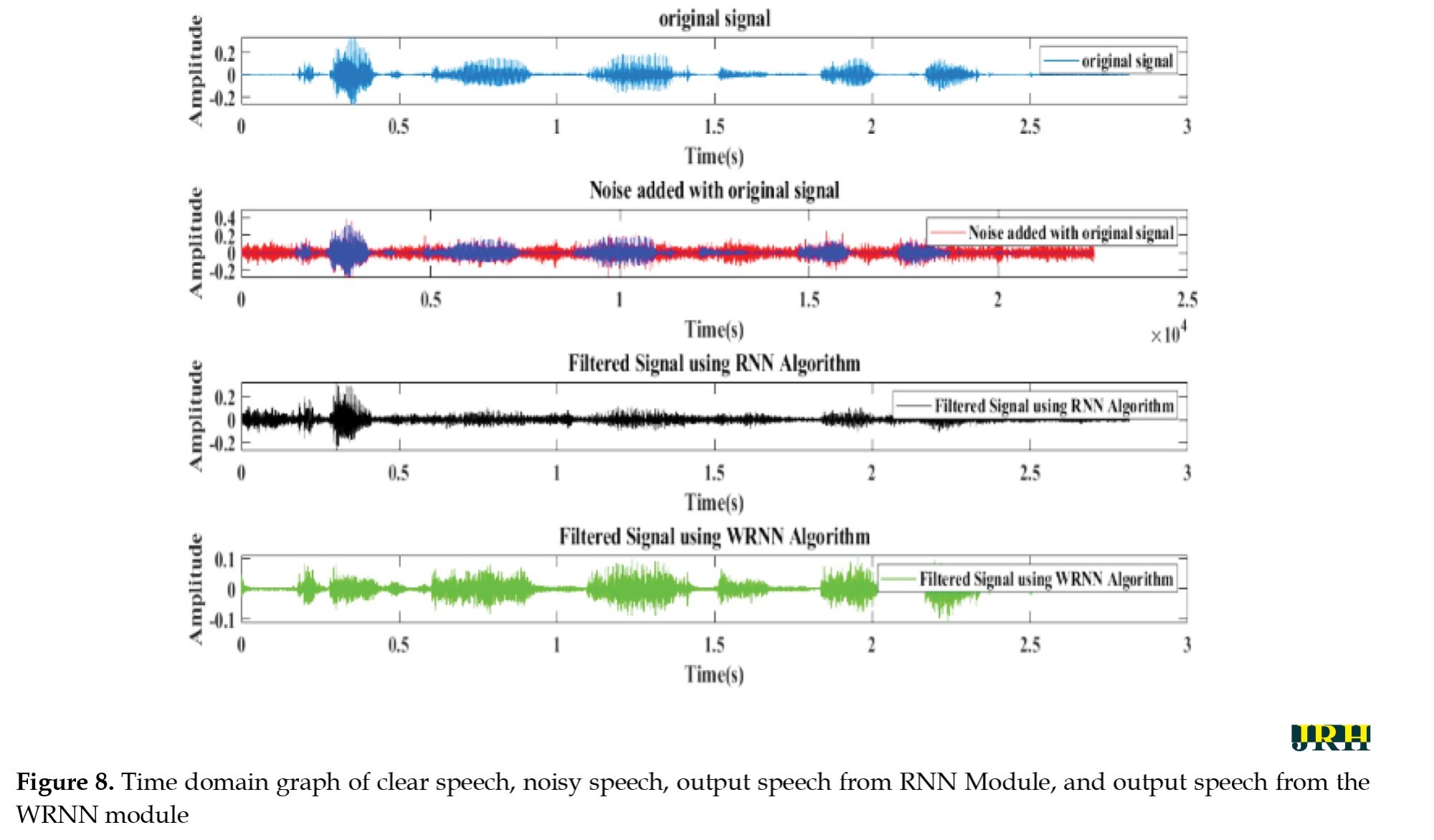

The time domain graph of clean speech, noisy speech, output speech from the RNN module, and output speech from the WRNN module is shown in Figure 8. It is clear that the module WRNN supressed almost all the noise components, resulting in an enhanced speech output compared to the existing RNN module.

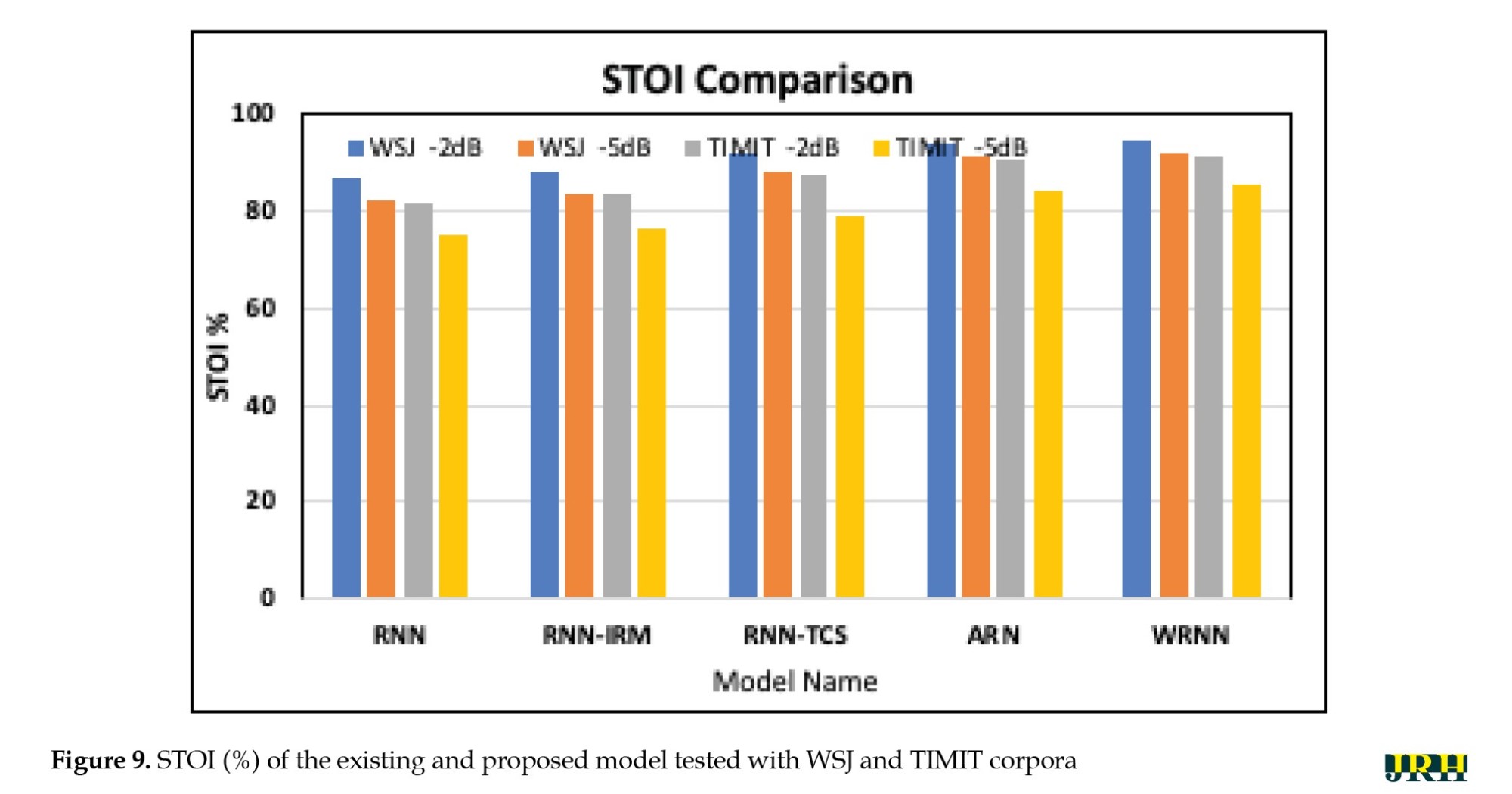

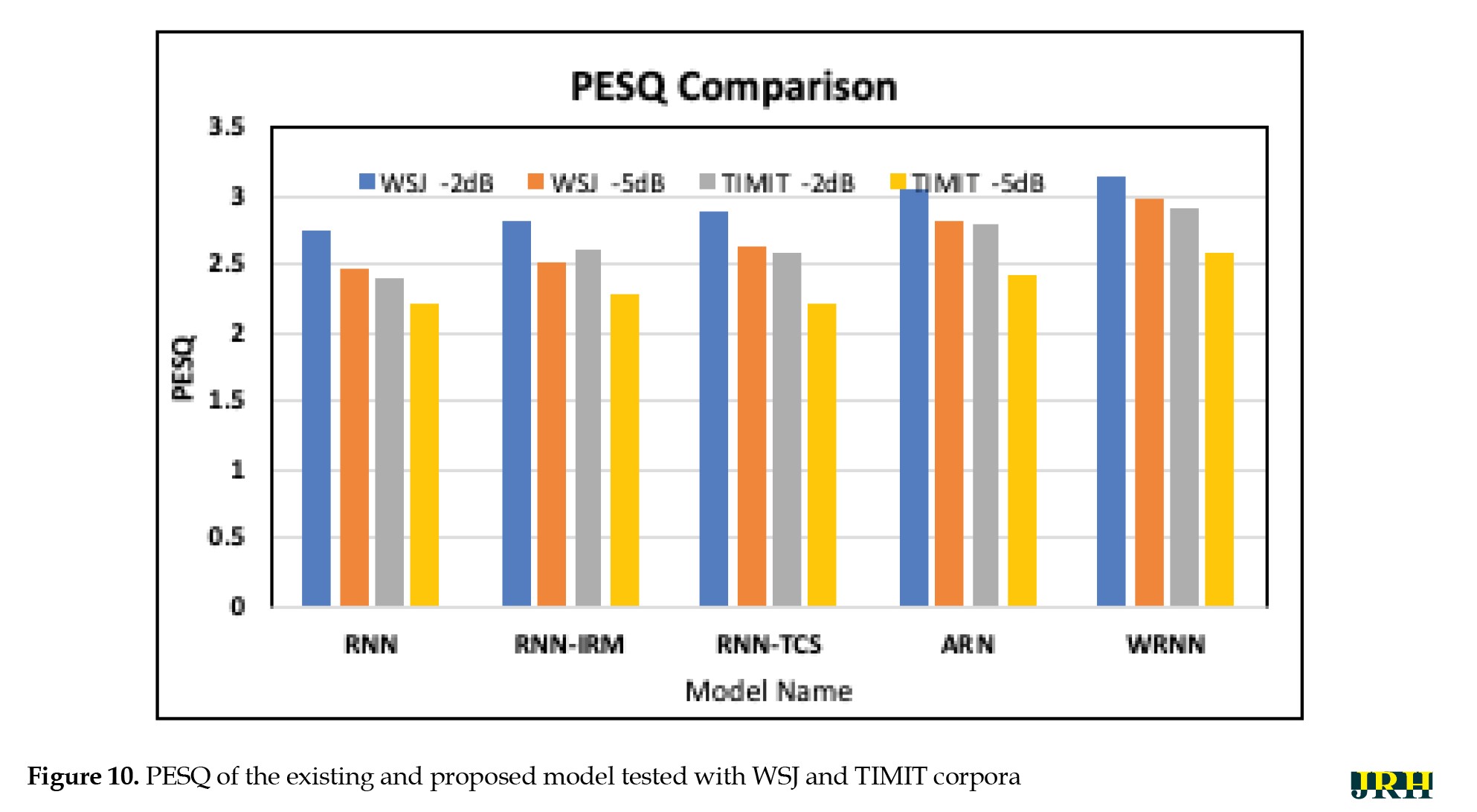

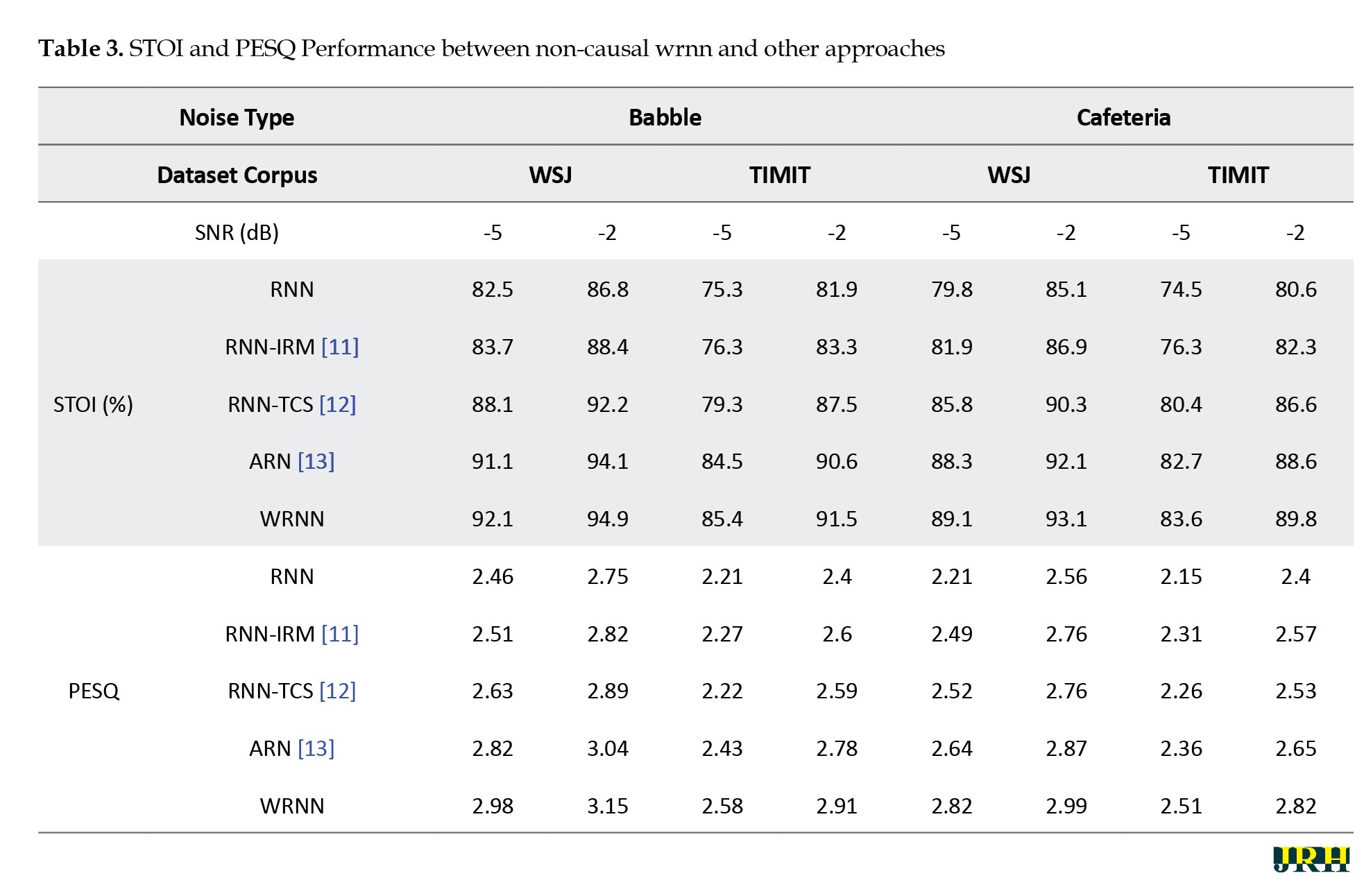

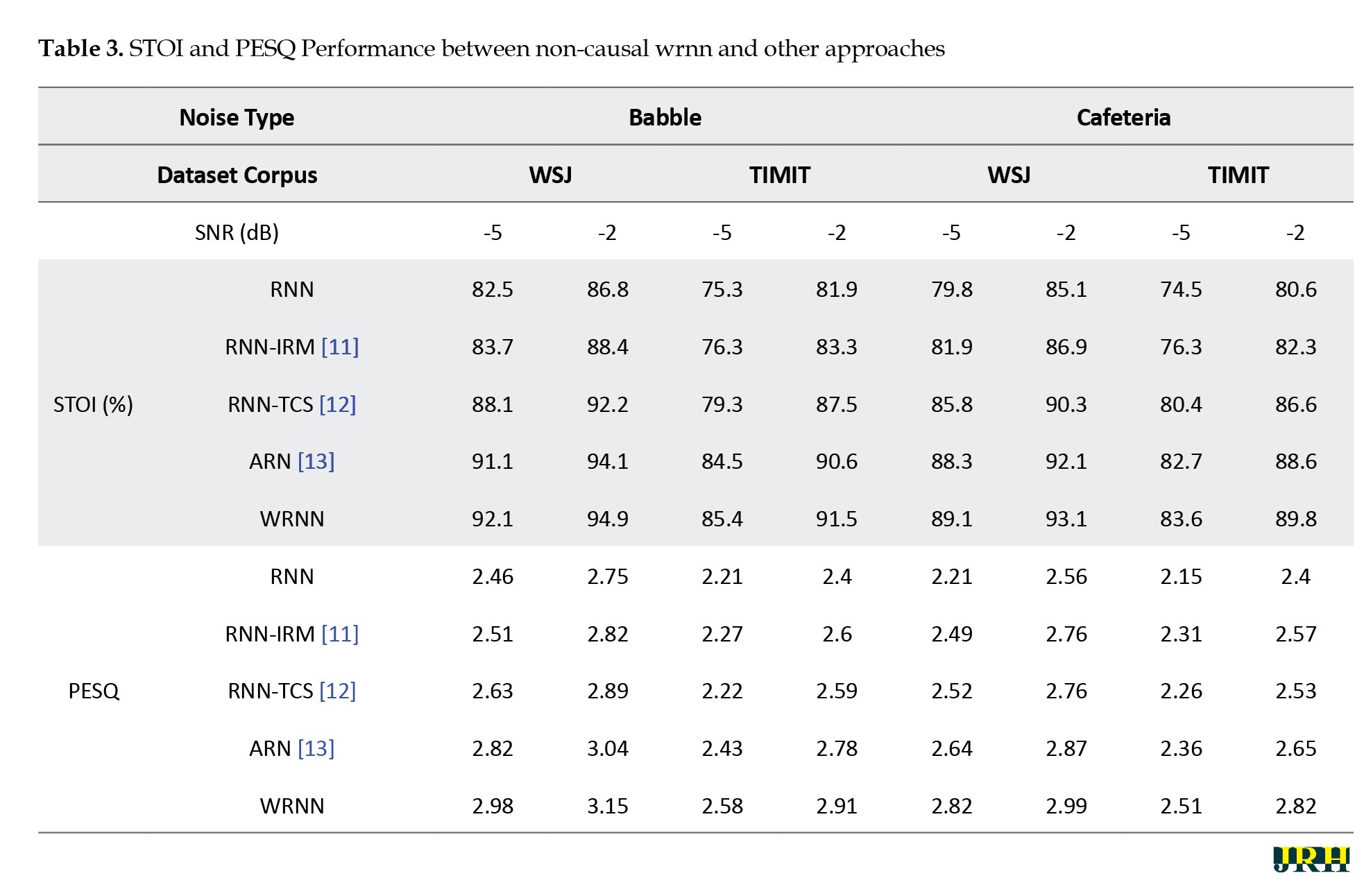

Figure 9 shows STOI (%) of the existing and proposed WRNN model tested with the WSJ and TIMIT corpora. The bar graph indicated the -5 dB and -2 dB SNR input noise levels. From the test results, it has been observed that the proposed WRNN model achieves better results compared to the existing four types. Figure 10 displays the PESQ of the existing and proposed WRNN model tested with the WSJ and TIMIT corpora. Table 3 shows the STOI and PESQ performance of both non-causal existing methods and the proposed method with different types of noise across different corpora.

For testing the models, we chose babble and cafeteria noise at -5 dB and -2 dB. Additionally, the same noisy signals were selected from different dataset corpora, such as WSJ and TIMIT. We compared the performance of the RNN and WRNN algorithms alongside RNN-IRM [11], RNN-TCS [12], and ARN [13]. Observations indicate that the WRNN produces excellent results compared to the other models. To measure the STOI parameter, we considered babble noise from the WSJ corpus, where the input at -5 dB and -2 dB SNR achieved scores of 92.1% and 94.9%, respectively. For the TIMIT dataset with the same type of noise, the scores were 85.4% and 91.5%.

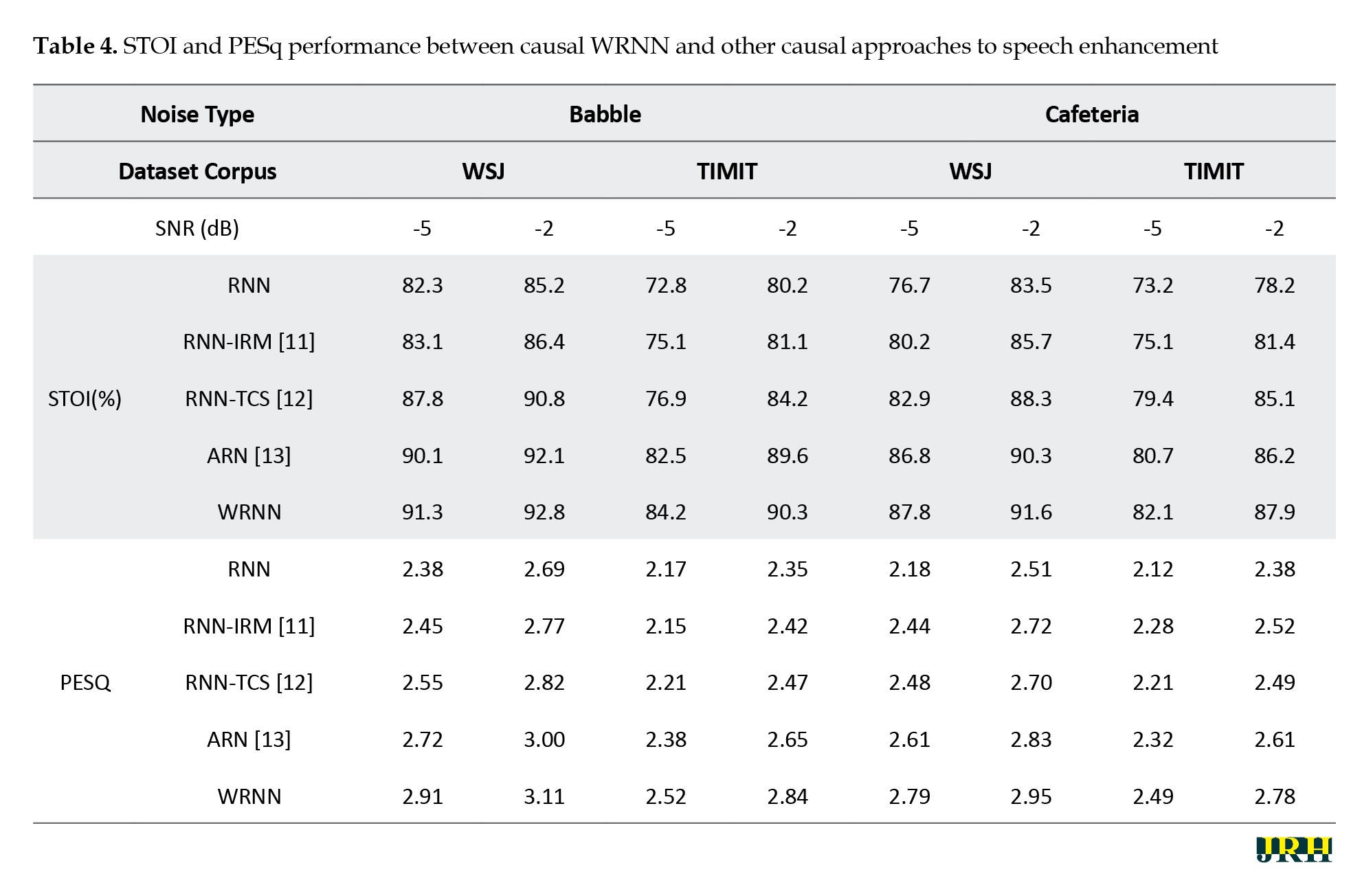

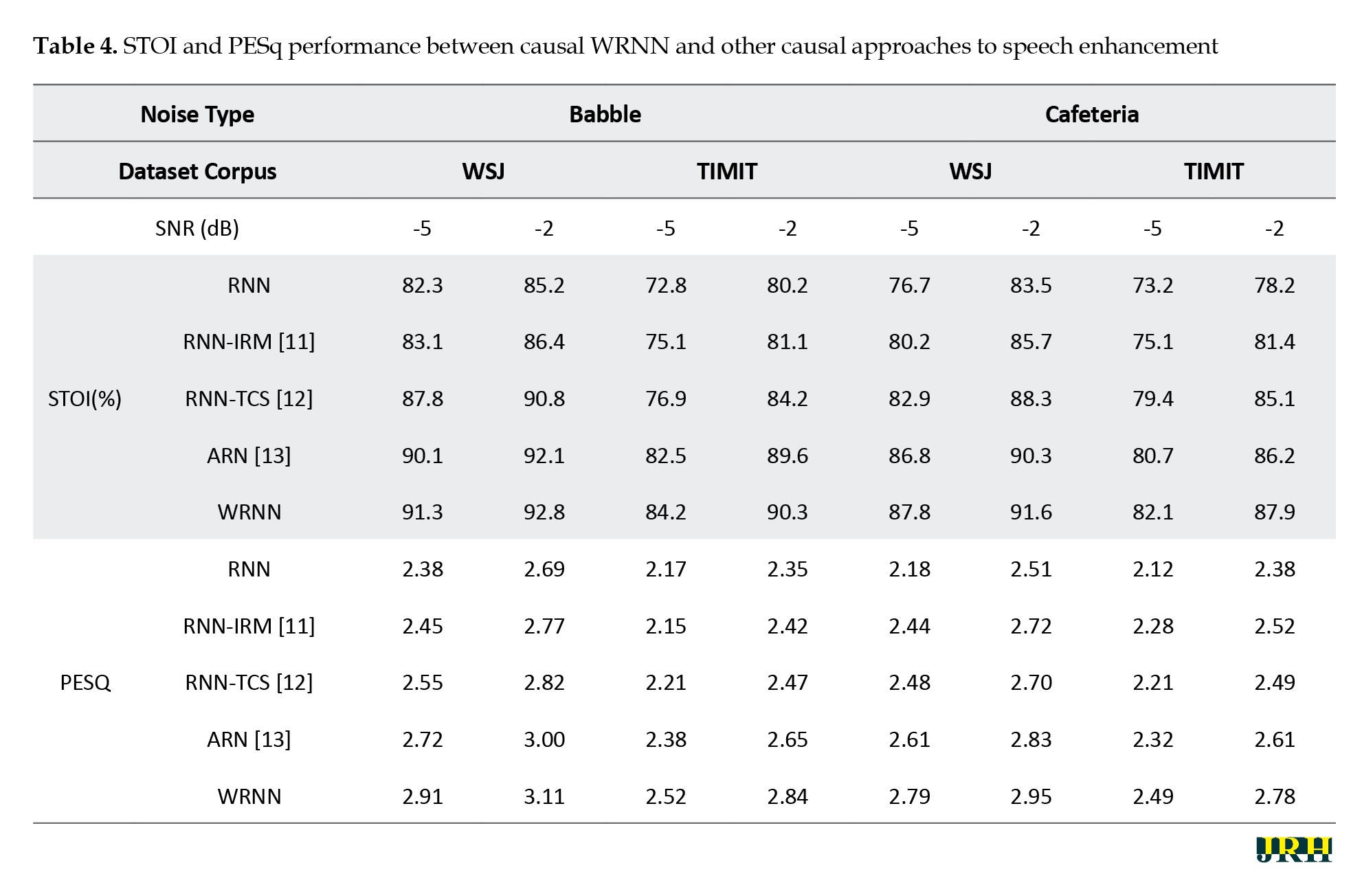

Table 4 shows the STOI and PESQ performance of causal existing methods compared to the proposed method with different types of noise across various corpora.

For testing the models, we again chose babble and cafeteria noise at -5 dB and -2 dB. Also, the same noisy signals were selected from different dataset corpora, like WSJ and TIMIT. Similarly, we tested another noise pattern, cafeteria noise, which also demonstrated a comparable improvement when compared with existing models. Additionally, we measured another speech quality test parameter, PESQ. For the PESQ parameter, babble noise from the WSJ corpus at -5 dB and -2 dB SNR yielded scores of 2.98 and 3.15, respectively, while the TIMIT dataset with the same type of noise resulted in scores of 2.58 and 2.91.

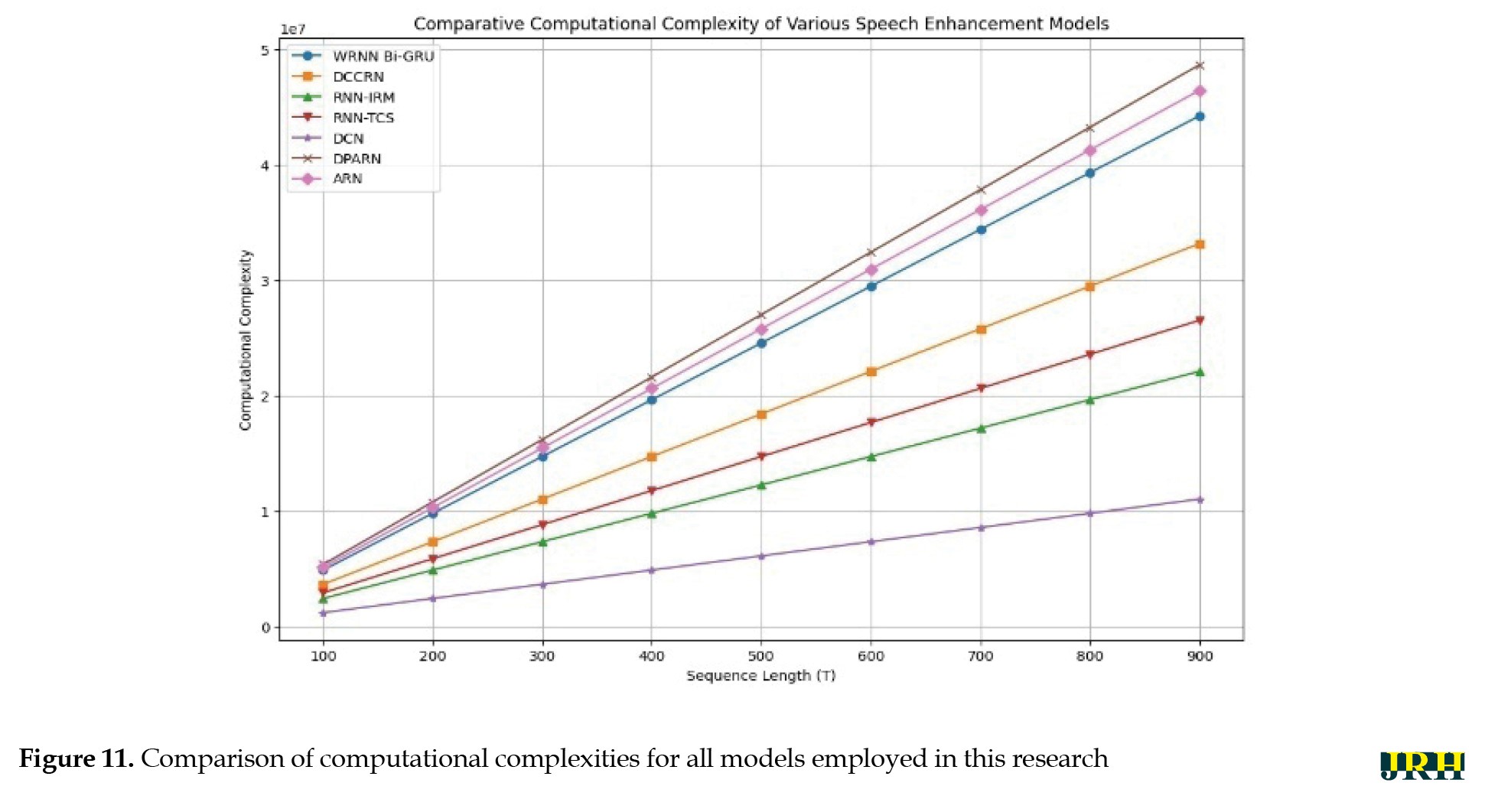

In this work, computational complexity was measured as the number of MACs per sequence lenths (T). The computational cost increased almost linearly with T for all models as shown in Figure 11. A moderate complexity profile was displayed by the WRNN Bi-GRU, which is lower than more complicated architectures, like DPARN and ARN but higher than lightweight models, like DCN, RNN-IRM, and RNN-TCS. Importantly, our primary results (STOI and PESQ) demonstrate that the WRNN achieves this balanced complexity while providing greater intelligibility and quality benefits.

Discussion

The outcomes of this research demonstrated the efficiency of the proposed WRNN framework for voice improvement in noisy environments. By utilizing both data-driven learning and statistical priors, the hybrid design greatly enhanced intelligibility and perceptual quality in comparison to traditional statistical techniques, like the standalone Wiener filter. While the Wiener filter offers reliable SNR estimates that maintain performance in low-SNR and non-stationary noise scenarios, the Bi-GRU network records temporal dependencies between frames.

The proposed WRNN model exhibited better performance in the removal of non-stationary and non-causal noise across the TIMIT and WSJ datasets; however, certain constraints exist. First, the evaluation was limited to two datasets, which might not accurately reflect the variety of acoustic characteristics found in real-world settings, such as low-resource languages or extremely reverberant surroundings. Second, without additional optimizations, like pruning or quantization, the direct application of the model in real-time or embedded systems is limited due to its comparatively higher complexity compared to traditional statistical techniques, which may result in increased computational costs and latency. Third, babbling noise was the primary focus of the experimental setup; further research is needed to assess performance against other challenging noise types, such as impulsive noise and mechanical interference. Lastly, although the Bi-GRU enhances temporal modeling, it is less effective than more recent transformer-based systems at capturing long-range dependencies. Future work will address these limitations by including a variety of noise types, expanding the evaluation to additional datasets, and investigating lightweight architectures for real-time deployment.

Even though the existing WRNN architecture successfully enhances speech by combining Wiener filtering and Bi-GRU, more advanced temporal modeling techniques could be advantageous for future developments. Integrating attention mechanisms to allow the model to selectively focus on informative temporal frames or spectral regions is one promising approach that could enhance performance in extremely dynamic noise environments. Furthermore, using transformer-based designs might improve the system’s capacity to recognize contextual linkages and long-range dependencies in speech sequences. Transformers may offer a more adaptable representation framework than recurrent models and have shown impressive performance in sequential data modeling across a variety of speech and audio challenges. The interpretability of the learnt representations, generalization across datasets, and noise robustness may all be enhanced by incorporating these methods into the WRNN framework. Moreover, hybrid systems that combine adaptive Wiener filtering with temporal self-attention may provide the optimal balance between enhancement quality and computational efficiency.

Conclusion

The proposed work used fusion technique to remove the background noise for non-stationary and non causal signals. In this work, two spectral domain speech estimators were examined using the Weiner estimator followed by an RNN to improve speech quality, adhering to the traditional speech augmentation processing paradigm. The collected findings showed that despite the RNN introducing very little distortion, the system based on the WRNN offered the best balance between speech augmentation in terms of quality measures and signal distortion.

The method’s speech enhancement performance was assessed on a simulated noisy speech database, comparing it with existing techniques such as RNN, RNN-IRM, RNN-TCS, and ARN against the proposed WRNN. This evaluation focuses solely on the Wiener filter estimation without using any compensations to address concerns with the estimating accuracy or training convergence. According to the results, the findings enhance the statistical-based WRNN by providing a reliable version that performs accurately in both synthetic and actual speech data. In terms of technological advancements, the results demonstrate that the proposed WRNN architecture is more effective at removing background noise.

The STOI parameter for testing model performance, considering babble noise from WSJ corpus, indicated that -5 dB and -2 dB SNR noise inputs achieved 92.1% and 94.9%, respectively, while the TIMIT dataset yielded 85.4% and 91.5% for the same noise types. The PESQ parameter, also testing model performance with babble noise from the WSJ corpus, showed values of 2.98 and 3.15 for -5 dB and -2 dB SNR noise inputs, respectively, while the TIMIT dataset produced values of 2.58 and 2.91 for the same noise types.

While the proposed work compared causal and non-causal approaches, the main objective of this work was to improve cross-corpus generalization and non-stationary noise removal. Comparing WRNN to existing methods, the number of parameters considered were greater, which has its own limitations. Future work will focus on evaluating the efficiency and computational complexity of the proposed model, including model compression and quantization, to optimize WRNN for practical applications.

In the future, researchers will explore ways to enhance the WRNN framework for real-time and embedded medical applications, such as hearing aids, mobile health monitoring systems, and telemedicine devices. These enhancements may include model compression, pruning, and quantization. Such improvements are designed to reduce the time and resources required to run the program while maintaining high performance. Also, the robustness of the proposed WRNN model can be evaluated using multilingual and biomedical corpora to ensure it performs effectively across different dialects, languages, and variations in physiological signals. Testing the model on clinical and real-world medical datasets will further show its applicability for healthcare-related signal enhancement tasks and its reliability.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Background noise often distorts and hides speech signals, making them difficult to hear clearly. To address this problem, speech enhancement techniques are used to reduce overlapping noise and make the speech clearer and more natural. The main purpose of a speech enhancement system is to reduce noise in a signal that has been contaminated. It works as a pre-processor for speech recognition systems, making the speech signal cleaner without changing the recognizer itself. These systems are crucial for various applications, including voice-controlled devices, audio restoration, automatic speech recognition, hearing aids, and telecommunications.

The enhancement of distorted speech using additive noise with a single observation has been accomplished; however, it remains a tough issue. Noise is introduced into the pristine speech sample to generate noisy speech with an SNR ranging from 0 to 0.5 dB in increments of 0.01 dB. The proposed model is divided into two phases: (i) Instruction and (ii) evaluation. During the training phase, the noise spectrum and signal spectrum are derived from the noisy input signal using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF). Subsequently, features from the Wiener filter are recovered using empirical mean decomposition (EMD) [1, 2]. This model integrates convolutional encoder-decoder and recurrent architectures to proficiently train intricate mappings from chaotic speech for real-time speech improvement, facilitating low-latency causal processing. Recurrent architectures, including long-short term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent unit (GRU), and simple recurrent unit (SRU), are utilized as bottlenecks to capture temporal dependencies and enhance the performance of speech enhancement. The model utilizes convolutional layers to effectively extract features from raw audio signals, along with layer normalization and bidirectional gated recurrent unit (Bi-GRUs) to capture long-range temporal relationships and contextual information from both preceding and subsequent frames. Substantial enhancements were observed across five training epochs, with the training and validation loss decreasing from 311.9084 to 70.7906 and from 303.5839 to 46.6886, respectively. Speech augmentation techniques have various applications, including hearing aids, voice-controlled devices, cellular phones, automatic speech recognition systems, and multiparty teleconferencing.

There are various methods for filtering the distorted signal. Each approach is distinct, considering numerous criteria and being specific to its application. In certain instances, it may be necessary to enhance speech quality, while in others, accuracy is paramount; achieving both quality and accuracy simultaneously within the same timeframe is challenging [3-5]. However, there are several limitations to spectrogram properties. The resulting signal contains artefacts as a result of the computationally intensive pre- and post-processing steps of the discrete fourier transform (DFT)and its inverse. Second, these techniques often only approximate the magnitude in order to produce the increased speech. Most of the research suggests that the phase can raise speech quality. Adding a specific model for the phase component or anticipating both magnitude and phase may add to model complexity, according to a recent study.

This study aimed to investigate a critical research question stemming from the challenges of speech enhancement in highly non-stationary environments: whether the proposed WRNN exhibits robustness in challenging conditions, such as low SNR levels and fluctuating noise amplitude or variance, in comparison to current state-of-the-art techniques.

Related work

Numerous traditional algorithms play a major role in acting as active noise cancellation (ANC) in speech applications, utilizing adaptive filters, Kalman filters, and Wiener filters. These techniques are widely employed in hearing aids and other edge devices, such as phones and communication devices, while Wiener filtering adapts to industry standards for dynamic signal processing. Contemporary smartphone designers frequently position two microphones at different angles from one another: one close to the speaker’s mouth to record loud speech and the other to assess background noise and filter it out. Signals that have been distorted by noise or other disturbances can be improved or restored using the Wiener filter. It has been extensively utilized in fields, including communications, audio signal improvement, and image processing.

The drawbacks of Wiener filter include the need for separation of audio streams to effectively benefit from it. In scenarios such as a cockpit or smartphone, while having two microphones is useful, it would also be advantageous to handle noise from a single stream. Additionally, when the spectral properties of the audio and the background noise overlap, audible distortions in the speech may occur. The filter’s subtractive design can eliminate speech segments that resemble background noise. These problems have been addressed with the support and development of deep learning (DL) [6].

RNN has never been used for waveform-based speech augmentation; the first application was to denoise a waveform that was not speech, and the second was to increase speech bandwidth. The high resolution of waveforms calls for networks that are broader, deeper, and more expensive. Building a deep RNN is difficult because saturated activation functions cause gradient degradation over layers. Furthermore, our research indicates that the size of the RNNs required for analyzing high-resolution waveforms demands larger RAM [7]. This systematic review analyzed speech improvement and recognition methodologies, focusing on denoising, acoustic modeling, and beamforming. An overview of various DL architectures, including deep neural networks (DNN), convolutional neural networks (CNN), recurrent neural networks (RNN), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and hybrid neural networks, emphasizes their contributions to enhancement and recognition [8]. It introduces UniInterNet, a unidirectional information interaction-based dual-branch network designed to facilitate noise modeling-assisted software engineering without increasing complexity. The noise branch still receives input from the speech branch to enhance the accuracy of noise modeling. The findings from noise modeling are then utilized to aid the speech branch during backpropagation. This research presents a complete framework for speech emotion recognition that integrates the ZCR, RMS, and MFCC feature sets.

Our methodology utilized both CNN and LSTM networks, augmented by an attention model, to improve emotion prediction. The LSTM model specifically tackles the issues of long-term dependency, allowing the system to include prior emotional experiences in conjunction with present ones [9, 10]. The Wiener filter is used to process the noisy speech signals and produce the clean speech targets. The RNN is then trained to use for minimizing mean squared error (MSE) or perceptual loss functions to decrease the difference between the target clean speech spectrum and the anticipated enhanced speech spectrum. The advantages of both strategies can be leveraged when the Wiener filter and RNN are used together compared to leading-edge techniques such as RNN-IRM [11], RNN-TCS [12], and RNN-ARN [13]. Studies have shown that advanced recurrent networks (ARN) perform better than other methods, like RNNs and dual-path ARNs, for improving speech in the time domain. Many contemporary smartphones are equipped with two closely positioned microphones. One microphone is positioned near the speaker’s lips to capture loud speech, while the other detects background noise and filters it out [14, 15]. For sparse noise, which is mostly very low frequency with high decibels, there is a chance that it may lead to noise-induced hearing loss, necessitating the use of a hybrid algorithm to control its occurrence [16].

In speech improvement tasks, the bi-GRU model is frequently employed to improve the quality of voice signals by lowering background noise. It utilizes the model’s bidirectionality to gather information from the input sequence’s past and future frames. The bi-GRU model is used in speech enhancement to process noisy speech signals in both forward and backward directions at the same time. This approach helps capture long-term dependencies and improves voice quality by enabling the model to learn representations that combine data from both previous and subsequent time steps.

Upon analyzing this approach, it was found that a deep structured network finds it difficult to appropriately estimate the infinte dynamic range of the SNR (−∞, ∞). For this reason, a compression function was used to prevent the convergence issues [17]. Moreover, SNR serves as a transitional stage before acquiring the Wiener filter function, which is needed to feed the SE algorithm. Therefore, the network’s ability to produce a more reliable estimate of the Wiener filter through direct learning is more practical.

The optimal use of the network for learning a robust instance of the Wiener filter estimator is found based on the properties of the speech enhancement algorithm’s intermediate phases, namely the SNR estimation and the gain function [18-22]. This work presented a novel DL model for sentiment analysis utilizing the IMDB movie reviews dataset. This model executes sentiment classification on vectorized reviews employing two Word2Vec methodologies, specifically Skip Gram and Continuous Bag of Words, over three distinct vector sizes (100, 200, 300), utilizing 6 bi-GRU and 2 convolutional layers (MBi-GRUMCONV). In the trials utilizing the suggested model, the dataset was divided into 80%-20% and 70-30% training-test sets, with 10% of the training subsets allocated for validation purposes.

Furthermore, it introduces a time-domain multi-channel Wiener filter algorithm for enhancing speech in the distributed speech model, aimed at recovering pure speech from observed speech. This paper initially presents the formula for the energy associated with noise reduction and speech distortion, subsequently formulates the optimization problem concerning these factors, and ultimately resolves the optimization problem to derive the formula for the optimal linear filter. This work employs an iterative technique to estimate the autocorrelation matrix of the source speech signal, thereby enhancing estimation accuracy. The findings of the simulation experiment indicate that the suggested approach outperforms numerous traditional multi-channel speech enhancement algorithms.

The problems identified in the traditional algorithm have motivated the proposal of a design for a reliable automatic signal detection and recognition system, which focuses on amplifying weak signals in the presence of channel noise and background interference. The distinguishing features, like SNR estimation and gain of input source waveforms or their spectra, can be mapped using the auto-associative property of the Wiener filter.

The novelty of the proposed work lies in utilizing the capabilities of Bi-GRU-based neural networks to create filters that first learn and then subtract background noise from the input waveform, thereby increasing the likelihood of detecting weak signals. Practical challenges in enhancing non-stationary and non-causal signals can be effectively addressed by a WRNN that learns to selectively filter out background noise without significantly affecting the signal.. Furthermore, using different corpora with non-stationary noises under low SNR conditions, in the presence of background noise and channel noise, a novel base WRNN filter improves signal detectability based on an analytical foundation.

Section 2 will explain the signal model and problem formulation. This section includes a block diagram, as well as discussions on pre-processing, noise removal, and post-processing. Section 3 will discusse the simulation results and provide a discussion on existing and proposed techniques, followed by conclusions.

Methods

Signal model and problem formulation

Noise can easily mixed with speech signals in real-world settings. Reverberations fall into two categories: stationary noise (which does not change over time) and non-stationary noise (which changes when shifted in time). Examples of background noise in the non-stationary category include street noise, babble noise, train noise, cafeteria noise (from other speakers’ voices), and instrumental sounds.

Block diagram of the proposed work

The proposed WRNN Model consists of three stages, namely pre-processing, noise reduction, and speech enhancement in post-processing, as shown in Figure 1.

Noisy speech input

A noisy speech signal—which includes both speech and undesired background noise—is used to initiate the procedure. The system’s objective is to improve voice quality by lowering noise levels.

Short-time fourier transform (STFT)

STFT is used to transform the time-domain loud speech into the time-frequency domain. To examine frequency components over time, STFT splits the signal into tiny frames and uses the Fourier transform. This facilitates the separation of speech and noise components.

Wiener filter

The Wiener filter is a traditional technique for reducing noise. It operates by minimizing the mean square error between the real and estimated clean signals. This block creates a spectrogram with reduced noise and provides initial noise suppression.

Bi-GRU layers (layers 1 & 2)

Following Wiener filtering, the features are fed into sophisticated RNN called Bi-GRU. In order to improve speech feature representation, Bi-GRU layers 1 and 2 progressively process information from both past and future contexts. This improves the ability to distinguish speech from noise and aids in modeling temporal connections.

Fully connected layer

A completely connected layer receives the processed features from the Bi-GRU layers. This layer maps the high-level learned features into the necessary format (e.g. predicted clean speech magnitude spectrogram). Essentially, it serves as a decision-making stage to complete the enhancement.

Inverse short-time fourier transform (ISTFT )

ISTFT is used to transform the improved spectrogram back into the time-domain waveform. The improved voice signal is reconstructed in this manner.

Enhanced speech output

The outcome is a clearer speech signal with diminished background noise and enhanced intelligibility.

Figure 2 depicts the proposed block diagram for speech enhancement with background non-sationary noise reduction. In a pre-processing stage, initially noisy data will undergo short-term windowing techniques, and this output will be applied to the STFT to obtain the phase and magnitude response. In second stage, which is the noise reduction stage, the Wiener filter function is used to calculate the gain factor and SNR estimation for the input features before moving to the post-processing stage. In the third stage, ISTFT is initially applied using an overlap-add convolution method to extract input features for the Bi-GRU-based RNN model, which is designed to remove non-stationary noise components from noisy speech. The detailed stage-wise explanation follows in the next section.

Pre-processing and database

To develop an accurate noise removal model, creating a high-quality training dataset is crucial. In this case, the TIMIT and WSJ databases were used to obtain clean speech and noisy speech data. These two databases were combined to create a larger dataset comprising a total of 7.5 hours of speech. The dataset was then split into separate portions: 60% for training, 20% for development, and 20% for testing.

During the construction of the dataset, certain considerations were taken into account. Firstly, the ratio of male to female speakers was balanced to ensure a diverse representation of voices. Additionally, it was ensured that there is no overlap of speakers between the different groups. This helps maintain the independence of the data subsets and prevents any bias that could arise from having the same speaker present in multiple sets.

The inclusion of both clean speech and its corresponding noisy counterpart in the dataset is essential because the objective is to reduce background noise. The nature of the dataset should align with the specific use case of the model being developed. For instance, if the model is intended to be used for noise removal in signals from a helicopter pilot’s microphone, it would be logical to train the network using auditory samples corrupted by rotor noise.

On the other hand, for a noise removal model intended for widespread use, incorporating authentic background noises, such as air conditioning, typing, dog barking, traffic, music, and loud conversations would be reasonable. The optimum way to use the network for learning a reliable Wiener filter estimator is defined by the properties of the speech enhancement algorithm’s intermediate phases, namely the gain function and SNR calculation. Studies demonstrate that the robustness of the statistical-based speech estimator technique stems from the data-driven learning process of the SNR estimator, resulting in high performance.

In the Equation 1:

where “x(n)” represents clear speech, “d(n)” stands for additive noise, and “n” represents the discrete-time index, the observed noisy speech signal is denoted as “y(n)”. To begin the pre-processing stage for speech enhancement in the spectral domain, the observed noisy speech signal “y(n)” is segmented into overlapping frames using a window function. This segmentation facilitates the analysis of the speech signal over shorter time intervals and captures the temporal characteristics of the signal. Following the segmentation, a STFT is applied to each frame. The STFT computes the spectrum representation of the signal by taking the Fourier transform of each frame. This transformation converts the speech signal from the time domain to the frequency domain, providing information about the spectral content of the signal at different frequencies. The STFT representation of the segmented frames can be represented as a matrix, where each column represents the frequency content of a specific frame. This matrix can be further processed using various speech enhancement techniques to decrease or eliminate the noise component and improve the excellence of the speech signal.

In the spectral-domain speech estimator method, as shown in Equation 2, various steps are involved. The equation includes the time frame index l’, the analytical window size y(n), and the number of samples between two frames denoted as Nand M. The input for the noise reduction block is the power spectrum, represented as , where l′ is the time frame index and k′ is the frequency frame index. The spectral phase is separated in the last post-processing step to facilitate voice reconstruction. The output of the system is an enhanced version of the noisy signal that closely resembles clear speech to the extent possible. The central block in the figure represents the core component of the enhancement technique. This concept is shared by the family of spectral-domain speech estimator methods.

However, it is important to note that in this particular instance, both the presence and absence of speech are considered separately. The filter gain function that modifies the power spectrum, denoted as , is determined using the gain of the minimum mean square error (MMSE) estimator, known as GMMSE. The GMMSE gain is based on the likelihood that speech is present in the signal. The spectral-domain speech estimation method calculates the filter gain function using various factors and techniques as Shown in Figure 3.

Noise simulation

To examine the effects of both variance and amplitude changes in background noise, controlled noise simulation was carried out in addition to using normal clean and noisy datasets. Gaussian and babbling noise samples with different noise strength levels were created for this purpose. A range of SNR circumstances (−5 dB, −2 dB, 0 dB, and +5 dB) were simulated by scaling the magnitude of the noise components. Likewise, variance scaling was used to simulate time-varying noise energy fluctuations. This provided us with the opportunity to investigate how the WRNN responds to abrupt and arbitrary variations in noise levels.

Noise reduction stage (wiener filter)

Wiener filtering is widely used as a standard dynamic signal processing technique in hearing aids and other auxiliary devices, like phones and communication equipment. It is an adaptive filter that performs optimally when provided with two audio signals - one containing both speech and background noise, and the other measuring only the background noise. Modern smartphones often incorporate two microphones placed at a distance from each other. One microphone is positioned near the speaker’s lips to capture the speech, which may be accompanied by noise, while the other microphone is dedicated to monitoring the background noise, enabling effective noise filtering.

Because it can anticipate and reduce noise, the Wiener filter is essential for both noise removal and augmentation. There are difficulties when integrating Wiener filters into big communication systems, including hardware needs and power consumption. The performance of the system was improved by employing the pipelined method. The proposed Wiener filter addressed iteration issues encountered in traditional designs by replacing the division operation with an effective inverse and multiplication operation. The architecture for matrix inversion was also redesigned to reduce computational complexity. Consequently, we directly expressed the Wiener filter’s gain function as Equation 3:

Where is the computed a priori SNR for each frequency k bin and time slice l.

For each variance of a spectral component, the gain function in the SS approach is, for example, defined as the square root of the maximum likelihood estimator. This can be explained by GMMSE as (β = 2) (Equation 4):

Regarding changes to this algorithm, several modifications have been researched. The a priori and a posteriori SNR are widely used to describe traditional speech enhancement algorithms. The a priori SNR is calculated using the PSD of the noise signal and the clean speech (Equation 5):

Where represents the clean speech PSD, refers to is the noise signal PSD, both in frequency bin k. The noise signal PSD and the noisy spectral power determine the a posteriori SNR (Equation 6).

As we can see, the a posteriori SNR may be derived utilizing the noisy spectral power along with an estimate of the PSD of the noise. To determine the noise spectrum, numerous statistical algorithms have been proposed. For instance, minima controlled recursive averaging (MCRA), minimal statistics, and histogram-based techniques, among others. Artificial neural networks, once a novel idea, have recently gained traction as DL. Despite the existence of various DL techniques for noise removal, they all operate by learning from training samples. Within the framework of the traditional spectral-domain speech estimator algorithm, the proposed work suggests a Wiener filter estimator for voice augmentation based on DL. The optimal use of the network for learning a robust version of the Wiener filter estimator is determined by the properties of the intermediate phases of the speech enhancement algorithm, namely SNR estimation and the gain function. Experiments demonstrate that employing data-driven learning of the SNR estimator yields state-of-the-art performance and provides resilience to the statistically-based voice estimator technique.

Post-processing (speech enhancement)

The post-processing stage proposes a solution to address the challenges by combining a GRU with learned speech features along with an adaptive Wiener filter. The main contributions of the proposed work can be summarized as follows:

(i) Modified wiener filter: The proposed work designs a modified version of the Wiener filter for decomposing the speech spectral signal to enhance the performance of speech by effectively separating the speech and noise components.

(ii) Introduction of Bi-GRU model: The Bi-GRU model is introduced to accurately estimate the tuning factor of the Wiener filter for each input signal. As a type of RNN, the Bi-GRU is capable of learning and capturing the temporal dependencies of the speech signal, which helps in determining the appropriate tuning factor for noise reduction.

(iii) Training with extracted features: The modified Wiener filter is used to train the GRU model by utilizing the extracted features obtained from the trial phase of the process called empirical mode decomposition (EMD). EMD captures relevant information about the speech and noise components that are used as input for the Bi-GRU model during the training phase. By combining the modified Wiener filter, the Bi-GRU model, and the extracted features from EMD, the proposed work aims to strengthen the accuracy and effectiveness of speech enhancement by dynamically adapting the Wiener filter based on the input signal characteristics.

For the voice augmentation challenge, advancements in DL have achieved excellent results, demonstrating the removal of background noise, including dog barking, kitchen noise, music, babbling, traffic, and outdoor sounds. The novelty of the proposed work lies in its effectiveness in attenuating both quasi-stationary and non-stationary noise compared to conventional statistical signal processing methods.

When the measured signal is minimally influenced by noise or is predominantly clean, the dynamic range of the SNR may increase due to the potential values used as outcomes, making regression more susceptible to errors in this situation. However, due to the influence of SNR on the GMMSE (Equation 7), high SNR conditions produce substantial gain values with GMMSE approaching 1, while low SNR conditions result in GMMSE approaching 0. As a result, the dynamic range needed to achieve regression for the GMMSE would be bounded between [0, 1], making it a task that a deep structured network is better equipped to perform.

Another factor that contributed to the choice of a deep structured network for this purpose was its ability to create a causal augmentation system. This implies that it can be utilized in online applications since it is not dependent on future time frames. The network also employs non-recursive estimating techniques to prevent the propagation of estimation errors from earlier frames. The previously stated statistical SNR-estimators often rely on recursive (feedback system) and causal algorithms.

The suggested RNN-based noise reduction technique is illustrated in Figure 4. The deep structured network was trained in a supervised manner using both noisy audio samples and clean audio samples as inputs. The objective of the network was to accurately predict the MMSE gain from the noisy signal based on Equations 2 and 4. To achieve this, the network needs to be aware of the power spectral density (PSD) of the noise, denoted as , and the PSD of the clean speech, denoted as , during the training process. These PSDs are estimated using the Welch approach, which is a commonly used method for PSD estimation.

Bi-GRU model

RNNs are capable of handling sequential data. As they work with the current data, RNNs can also retain knowledge from earlier data. The GRU is a less complex version of the GRU, both of which are enhanced RNN models with potent modelling skills for long-term dependencies [20]. A reset gate and an update gate make up a GRU unit. Under the direction of these two gates, the output ht is governed by both the present input and the preceding state h(t−1). The outputs of the gates and the GRU unit are calculated using Equation 8.

Where Wr,Ur,Wz,Uz,Wh, and Uh are the weight matrices, and br,bz, and bh are the bias vectors. Equation 7 represents the equations used in the GRU model, where xt is the input at time step t, ht−1 is the previous hidden state, and rt,zt, and ht are the update gate, reset gate, and current hidden state, respectively, at time step t. The update gate rt controls how much of the previous hidden state should be considered for the current time step, while the reset gate zt determines how much of the previous hidden state should be ignored. These gates are computed using the logistic sigmoid function σ. The hidden state ht is computed based on the input , the previous hidden state ht−1 and the update and reset gates. The Hadamard product, , is used to combine the input and the previous hidden state with the update gate, and the hyperbolic tangent function (tanh) is applied to obtain the current hidden state.

When working with sequential data, models with a bi-directional structure have the capability to learn information from both past and future data points. Figure 5 illustrates the structure of the bi-GRU model. It consists of two GRUs, one moving forward and the other moving backward. The first GRU processes the input sequence from the beginning to the end, capturing the dependencies in the forward direction. The second GRU processes the input sequence in reverse, starting from the end and moving toward the beginning, capturing the dependencies in backward direction [21]. By combining the outputs of the forward and backward GRUs, the bi-GRU model incorporates information from both past and future contexts, allowing it to have a more comprehensive understanding of the input sequence at each time step.

In Equation 9, is represented by the state of the forward GRU, similarly Equation 10, is reprsented by the state of the backward GRU and Equation 11 is represented by overall i.e Bi-diectional GRU states and indicates the operation of concatenating two vectors. In the Equations 9, 10 and 11, GRUfwd represents the hidden state of the forward GRU at time step t, GRUbwd represents the hidden state of the backward GRU at time step t, and xt is the input at time step t. Additionally, and represent the hidden states of the forward and backward GRUs from the previous and subsequent time steps, respectively. The output of the bi-GRU at each time step, ht, is a concatenation of the forward and backward hidden states, providing a richer representation that incorporates information from both directions.

The GMMSE was calculated using a GRU-based RNN design with multiple inputs based on 1-dimensional convolutions. The MATLAB tool was utilized to generate the patterns. The front end of the system employed a set of speech representations computed on a 25 ms Hamming window frame with a 10 ms overlap.

This included calculating a 512-dimensional FFT, 32 Mel filter banks, and 32 cepstral features. These features were then stacked to create a single input feature vector for the network for each frame slice. To normalize the input data, the mean and variance of the training samples were used. During the training process, input features were generated on the fly, which allowed the system to compute mask predictions for each time-frequency area in a single forward pass while calculating the average loss to determine the gradients. For training the network, each audio file in the training set was divided into two-second segments, equivalent to 200 frames. A batch of 32 of these segments was then used to train the network. During the evaluation phase, the mask inference was computed for each speech in the evaluation group.

To train a deep neural network, a 1-D CNN was employed to classify the sequence data and learn its features by applying sliding convolutional filters to the 1-D input. Because convolutional layers can process the input in a single operation, employing 1-D convolutional layers can potentially be faster than utilizing recurrent layers. Recurrent layers, on the other hand, have to repeat across the input’s time steps. The normalized molecular property of the sequence data was then extracted using a 1D CNN. Moreover, temporal characteristics were retrieved from the extracted data using GRU layers. The system’s design comprised five Bi-GRU blocks, each with an increasing number of channels. The specific details of the network dimensions of the architecture used for estimating GMMSE are provided in Table 1.

Applications of WRNN in medical signal enhancement

The suggested WRNN model had significant potential for processing medical signals, particularly for eliminating noise in biomedical acoustic signals such as phonocardiograms and respiratory sounds. In telemedicine and assistive hearing applications, environmental and physiological noise can obscure clinically significant characteristics. By effectively removing non-stationary noise components, the hybrid WRNN framework can enhance these signals, making automated analysis systems more reliable for diagnosis. Furthermore, the proposed model’s ability to maintain speech clarity while reducing distortion is highly beneficial for real-time monitoring and communication with patients in speech-based pathological assessments and hearing aids.

Results

Simulation results

Figure 6 shows the training progress response for the WRNN model. Table 2 provides the hyperparameters and settings for the proposed model.