Volume 10, Issue 4 (Jul & Aug 2020)

J Research Health 2020, 10(4): 239-248 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ahmadi L, Panaghi L, Sadeghi M S, Zamani Zarchi M S. The Mediating Role of Personality Factors in the Relationship Between Family of Origin Health Status and Marital Adjustment. J Research Health 2020; 10 (4) :239-248

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-1588-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-1588-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Family Research Institute (FRI), Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Community Medicine, Family Research Institute (FRI), Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran. , Zamani.1370@yahoo.com

2- Department of Community Medicine, Family Research Institute (FRI), Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran. , Zamani.1370@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 827 kb]

(852 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1753 Views)

Full-Text: (2026 Views)

1. Introduction

A Marital relationship is described as the most important and basic human relationship because it provides the basic and primary structure for building family relationships and nurturing the next generation [1]. For most adults, happiness in life is more dependent on successful marriage and marital relations than on other components of life. Research evidence indicates that low-quality relationships affect people’s mental and physical health [2].

Marital adjustment is defined as a process in which an individual or a couple modifies, adopts, or changes their behavior pattern and interaction to gain maximum satisfaction in their relationship [3]. Compatible couples are those who get along well, are happy with the type and level of relationships, are satisfied with the quality of the leisure time, and handle their own time and finances well [4].

Although many factors are involved in predicting marital adjustment, factors pertaining to couples’ family of origin are of particular importance [5], because an individual’s perception of early experiences in the family of origin may affect his or her marriage and marital relationship [6]. According to Bowen’s multi-generational theory, people learn the foundations of interpersonal relationships in their family of origin. Even if people stay away from the place of their family of origin, their beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, self-esteem, and interaction patterns are affected. These effects occur in positive and negative ways [7].

Studies have shown that warmth, affection, and intimacy in the family are predictors of the quality of intimate relationships in children’s marriage [8]. Raising children in the family of origin is of particular sensitivity and brings the development of talent, creativity, innovation, adoption of norms, patterns, social values, commitment, responsibility, independence, freedom, and so on. If the family of origin lacks a good level of physical and mental health, the upbringing of children will be negatively affected and this process makes their mental health, development, and future success hard and problematic.

As previously stated, the family of origin can play a key role in the quality of marital relationships of children. Several studies have shown that parents’ relationship with their children and their performance influences the children’s independence from the family, their marital satisfaction in the future life, and their communications. Lewis, Spanier, Larsen, and Holman stated that the quality of parent-child relationships in the family of origin would predict stability and marital satisfaction in couples’ future life [9]. Dennison, Koerner, and Segrin reported that the family of origin features (such as divorce and conflict) is associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction, especially in women [10].

Johnson, Nguyen, Anderson, Liu, and Vennum [11] conducted research using dyadic data from 200 young adult couples (aged 18–31 years). The current study evaluated direct and indirect associations between the family of origin dysfunction and intimate relationship success via the potential mediators of mental health problems and negative couple interactions. The results demonstrated that male partner family dysfunction was associated directly and indirectly with lower relationship success via negative couple interaction. Female partner family dysfunction was related to their reduced relationship success via mental health problems and less relationship success for male partners via mental health problems and negative couple interaction.

Falcke, Wagner, and Mosmann [12] aimed to analyze which experiences with the family of origin might be associated with better or worse levels of quality in marital adjustment. They investigated a sample of 542 Brazilians, all belonged to the average socioeconomic level. Their results showed an association between the type of experience that the participants lived in their families of origin and the quality of their marital relationship. The findings suggested a relationship between the legacies that people bring from their families of origin and their later marital adjustment.

Studies on 57 couples have shown that divorce and conflict in the family of origin predict the likelihood of violence, the disintegration of marriage, and lack of problem-solving skills in children. Also, people’s behaviors, interpersonal relationships, and marital quality are formed and predicted by experiences from the family of origin [13]. Also, several studies explored the connections between experiences within the family of origin and adult experiences in marital life and showed that family of origin experiences affect people’s marital relationships [14-16].

In addition to the family of origin, personality traits can also form the overall quality of an individual’s relationship, and the quality of the relationship, in turn, affects the possibility of dissolution of relationships [17]. Personality traits refer to the stable characteristics and patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior which remain constant over time and describe the individual’s behavior in different situations [18].

Bowlby suggested that the quality of childhood relationships, especially the child-caregiver relationship profoundly affects the personality and the concept of self and others. Bowlby hypothesized that children internalize their own experiences with the caregiver in a way that these relationships would get extra-familial patterns. He called these patterns “intrawork patterns”. These patterns affect an individual’s expectations, perceptions, and behavior in adulthood [19]. On the other hand, the dynamic equilibrium model suggests that personality plays a critical role in compatibility. This model is used to explain why people provide constant reports of events for their negative or adaptive experiences.

Headey and Wearing [20] believed that everyone has a normal level of balance, compatibility, and psychological comfort and this balance level is predictable by personality traits. In other words, although the new positive and negative changes may lead to an imbalance in the level of psychological comfort and compatibility, personality traits can play an important role in maintaining the normal balance [21]. For example, neuroticism as an aspect of personality is closely related to compatibility, and if the person is high in this aspect, signs of incompatibility are likely to remain in a lifetime [22].

The literature review indicates that couples’ personality traits are of the most important factors affecting life satisfaction and explain changes in marital satisfaction and marital adjustment. Research studies show that marital satisfaction and marital adjustment receive the greatest impact from couples’ personality traits [23]. DEARR (The development of early adult romantic relationships) model suggests that the family of origin experiences indirectly through individual characteristics such as cognitive, emotional, and behavioral characteristics affect couples’ relationships. Anderson, Johnson, Liu, Zheng, Hardy, and Lindstrom [24] in their study through structural equation modeling showed that family dysfunction indirectly and through depressive symptoms was associated with success in romantic relationships. Couples who express more negative emotions toward each other, report poorer marital adjustment compared with those who expressed positive emotions [25].

Watson et al. [26] confirmed the relationship between personality traits and marital adjustment and consider conscientiousness as one of the factors associated with marital satisfaction. Also, lower levels of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience can be a source of marital dissatisfaction. A husband or wife who feels no or a little stability, is not dutiful (consciousness), experiences lower levels of agreeableness and openness, and makes his partner dissatisfied [27].

Regarding what was mentioned, this study aims to explain a conceptual model of predicting marital adjustment based on family (e.g., family of origin health) and individual (e.g., personality characteristics) factors in married women and men in Iran. The increase of marital problems, dissatisfaction, and conflict, the higher divorce rate in recent years, and its adverse consequences has highlighted the need and importance of considering the issue of relations between spouses. Therefore, understanding the determinative variables which affect marital adjustment will help to prevent problems and improve community health.

2. Methods

The present research was correlational and used structural equation modeling. The study participants included 300 married adults (150 men and 150 women) living in Qazvin City, Iran who passed at least one year of their marriage. The sample size was determined based on Kline’s view about structural equation modeling [28]. These participants were selected via the available sampling method. Questionnaires were distributed in various places such as universities, entertainment venues, institutions, firms, and community centers in five districts of Qazvin (North, South, West, East, and Centre). The Mean±SD duration of marriage in participants was 11.05±8.07 and the Mean±SD age of participants was 34.51±7.900. Regarding the education, 9.33% of the participants were low literate, 36% had diplomas, 46% were undergraduate, and 8.60% had MS or PhD.

Data collection tools in this study comprised three tools: NEO-five factor inventory (NEO-FFI), the family of origin scale (FOS), and dyadic adjustment scale (DAS).

NEO-five factor inventory (NEO-FFI)

The NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) is a revised version of Costa and McCrae’s NEO personality inventory [22]. This questionnaire has a short form called NEO-FFI which has been used in this study. The NEO-FFI [29] is a 60-item self-report instrument used to measure the five personality domains according to the FFM: N, E, O, A, and C (12 items per domain). The NEO-FFI includes self-descriptive statements that participants respond to them using a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert-type scale. Scores for each domain are calculated by summing the 12 item responses with a score from 0 to 48. Costa and McCrae have reported the alpha coefficients of 0.68 (for agreeableness) to 0.86 (for neuroticism) [29].

They also suggested that the shortened version is consistent with the long-form; so that the short-form scales are more than 0.68 correlated with the full version. This explains 85% of the variance in convergent validity. They conducted a 7-year longitudinal study of peer assessment where the test was used and achieved a reliability coefficient between 0.82 to 0.51 for 18 secondary traits of N, E, O, and 0.81 to 0.61 for five main factors. The Cronbach alpha coefficients for each of the main factors of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness were respectively 0.86, 0.73, 0.56, 0.56, and 0.87.

Family of Origin Scale (FOS)

The family of origin scale is a retrospective instrument in which individuals rate the family in which they were raised. Conceptually, the FOS is based upon two overarching constructs-autonomy and intimacy-each of which is represented by five subscales. In this model, a healthy family gives independence to its members through clarity of expression, personal responsibility, respect for the other family members, openness to others in the family, and acceptance of separation and loss. At the same time, the healthy family creates intimacy in family through the expression of a wide range of feelings, creating a warm atmosphere at home, dealing with conflicts without undue stress, promoting sensitivity in family members, and trusting in the goodness of human nature [30].

FOS is a 40-item measure with each item rated on a 1 to 5 Likert-type scale according to the respondent’s level of agreement with each statement (1.strongly disagree; 5. strongly agree) [30]. The highest rating “5” is awarded to an option that is close to health and the lowest rating “1” to an option that is close to a lack of health. The minimum score is 40 and the maximum is 200. Higher scores indicate a better perception of the health of the family of origin.

Traditional psychometric studies consistently found that the FOS was reliable. There was also evidence of discriminant validity with some support for construct validity. Hovestadt et al. in a study on original FOS reported two weeks test-retest reliabilities of 0.97 for the whole scale with a median of 0.77 for the 20 autonomy items and 0.73 for intimacy. The internal consistency, as measured by the Cronbach alpha, was 0.97 [30].

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)

This scale is a tool that is widely used in assessing the compatibility in relationships and is one of the most useful tools in the field of marriage and family [31]. This 32-item Likert-type self-report instrument is used to assess marital relationship quality and measures four aspects of the relationship: dyadic satisfaction, dyadic cohesion, dyadic consensus, and affectional expression. The total score is from 0 to 150 which is obtained by summing the scores of questions. Some questions should be reversed for scoring [32].

The scale is of considerable internal consistency. Carey, Spector, Lantinga, and Krauss in examining the validity of this scale, achieved high internal consistency (0.95) [33]. Spanier reported the validity of the scale as 0.96. He also reported the concurrent validity of the scale as 0.86 based on correlation with Locke and Wallace’s marital adjustment questionnaire [34].

3. Results

The data were analyzed using structural equation modeling procedures and bootstrap testing.

Descriptive statistics for study variables

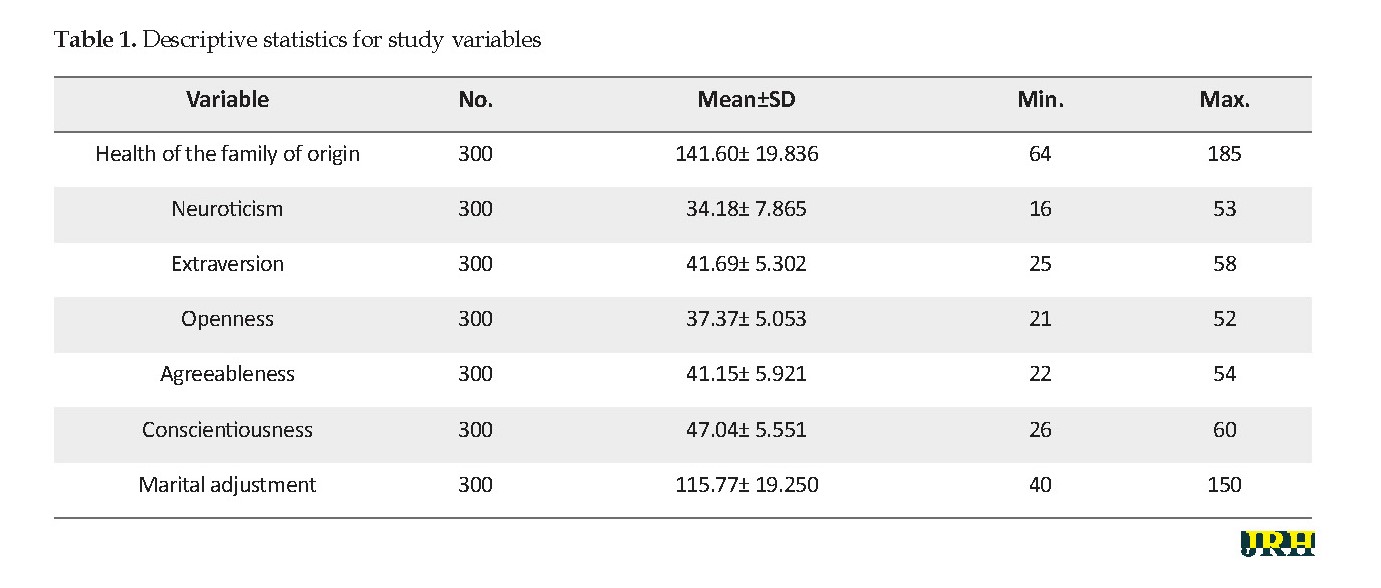

In table 1, the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum amount of study variables (the health of the family of origin, five personality traits, and marital adjustment) are reported.

A Marital relationship is described as the most important and basic human relationship because it provides the basic and primary structure for building family relationships and nurturing the next generation [1]. For most adults, happiness in life is more dependent on successful marriage and marital relations than on other components of life. Research evidence indicates that low-quality relationships affect people’s mental and physical health [2].

Marital adjustment is defined as a process in which an individual or a couple modifies, adopts, or changes their behavior pattern and interaction to gain maximum satisfaction in their relationship [3]. Compatible couples are those who get along well, are happy with the type and level of relationships, are satisfied with the quality of the leisure time, and handle their own time and finances well [4].

Although many factors are involved in predicting marital adjustment, factors pertaining to couples’ family of origin are of particular importance [5], because an individual’s perception of early experiences in the family of origin may affect his or her marriage and marital relationship [6]. According to Bowen’s multi-generational theory, people learn the foundations of interpersonal relationships in their family of origin. Even if people stay away from the place of their family of origin, their beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, self-esteem, and interaction patterns are affected. These effects occur in positive and negative ways [7].

Studies have shown that warmth, affection, and intimacy in the family are predictors of the quality of intimate relationships in children’s marriage [8]. Raising children in the family of origin is of particular sensitivity and brings the development of talent, creativity, innovation, adoption of norms, patterns, social values, commitment, responsibility, independence, freedom, and so on. If the family of origin lacks a good level of physical and mental health, the upbringing of children will be negatively affected and this process makes their mental health, development, and future success hard and problematic.

As previously stated, the family of origin can play a key role in the quality of marital relationships of children. Several studies have shown that parents’ relationship with their children and their performance influences the children’s independence from the family, their marital satisfaction in the future life, and their communications. Lewis, Spanier, Larsen, and Holman stated that the quality of parent-child relationships in the family of origin would predict stability and marital satisfaction in couples’ future life [9]. Dennison, Koerner, and Segrin reported that the family of origin features (such as divorce and conflict) is associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction, especially in women [10].

Johnson, Nguyen, Anderson, Liu, and Vennum [11] conducted research using dyadic data from 200 young adult couples (aged 18–31 years). The current study evaluated direct and indirect associations between the family of origin dysfunction and intimate relationship success via the potential mediators of mental health problems and negative couple interactions. The results demonstrated that male partner family dysfunction was associated directly and indirectly with lower relationship success via negative couple interaction. Female partner family dysfunction was related to their reduced relationship success via mental health problems and less relationship success for male partners via mental health problems and negative couple interaction.

Falcke, Wagner, and Mosmann [12] aimed to analyze which experiences with the family of origin might be associated with better or worse levels of quality in marital adjustment. They investigated a sample of 542 Brazilians, all belonged to the average socioeconomic level. Their results showed an association between the type of experience that the participants lived in their families of origin and the quality of their marital relationship. The findings suggested a relationship between the legacies that people bring from their families of origin and their later marital adjustment.

Studies on 57 couples have shown that divorce and conflict in the family of origin predict the likelihood of violence, the disintegration of marriage, and lack of problem-solving skills in children. Also, people’s behaviors, interpersonal relationships, and marital quality are formed and predicted by experiences from the family of origin [13]. Also, several studies explored the connections between experiences within the family of origin and adult experiences in marital life and showed that family of origin experiences affect people’s marital relationships [14-16].

In addition to the family of origin, personality traits can also form the overall quality of an individual’s relationship, and the quality of the relationship, in turn, affects the possibility of dissolution of relationships [17]. Personality traits refer to the stable characteristics and patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior which remain constant over time and describe the individual’s behavior in different situations [18].

Bowlby suggested that the quality of childhood relationships, especially the child-caregiver relationship profoundly affects the personality and the concept of self and others. Bowlby hypothesized that children internalize their own experiences with the caregiver in a way that these relationships would get extra-familial patterns. He called these patterns “intrawork patterns”. These patterns affect an individual’s expectations, perceptions, and behavior in adulthood [19]. On the other hand, the dynamic equilibrium model suggests that personality plays a critical role in compatibility. This model is used to explain why people provide constant reports of events for their negative or adaptive experiences.

Headey and Wearing [20] believed that everyone has a normal level of balance, compatibility, and psychological comfort and this balance level is predictable by personality traits. In other words, although the new positive and negative changes may lead to an imbalance in the level of psychological comfort and compatibility, personality traits can play an important role in maintaining the normal balance [21]. For example, neuroticism as an aspect of personality is closely related to compatibility, and if the person is high in this aspect, signs of incompatibility are likely to remain in a lifetime [22].

The literature review indicates that couples’ personality traits are of the most important factors affecting life satisfaction and explain changes in marital satisfaction and marital adjustment. Research studies show that marital satisfaction and marital adjustment receive the greatest impact from couples’ personality traits [23]. DEARR (The development of early adult romantic relationships) model suggests that the family of origin experiences indirectly through individual characteristics such as cognitive, emotional, and behavioral characteristics affect couples’ relationships. Anderson, Johnson, Liu, Zheng, Hardy, and Lindstrom [24] in their study through structural equation modeling showed that family dysfunction indirectly and through depressive symptoms was associated with success in romantic relationships. Couples who express more negative emotions toward each other, report poorer marital adjustment compared with those who expressed positive emotions [25].

Watson et al. [26] confirmed the relationship between personality traits and marital adjustment and consider conscientiousness as one of the factors associated with marital satisfaction. Also, lower levels of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience can be a source of marital dissatisfaction. A husband or wife who feels no or a little stability, is not dutiful (consciousness), experiences lower levels of agreeableness and openness, and makes his partner dissatisfied [27].

Regarding what was mentioned, this study aims to explain a conceptual model of predicting marital adjustment based on family (e.g., family of origin health) and individual (e.g., personality characteristics) factors in married women and men in Iran. The increase of marital problems, dissatisfaction, and conflict, the higher divorce rate in recent years, and its adverse consequences has highlighted the need and importance of considering the issue of relations between spouses. Therefore, understanding the determinative variables which affect marital adjustment will help to prevent problems and improve community health.

2. Methods

The present research was correlational and used structural equation modeling. The study participants included 300 married adults (150 men and 150 women) living in Qazvin City, Iran who passed at least one year of their marriage. The sample size was determined based on Kline’s view about structural equation modeling [28]. These participants were selected via the available sampling method. Questionnaires were distributed in various places such as universities, entertainment venues, institutions, firms, and community centers in five districts of Qazvin (North, South, West, East, and Centre). The Mean±SD duration of marriage in participants was 11.05±8.07 and the Mean±SD age of participants was 34.51±7.900. Regarding the education, 9.33% of the participants were low literate, 36% had diplomas, 46% were undergraduate, and 8.60% had MS or PhD.

Data collection tools in this study comprised three tools: NEO-five factor inventory (NEO-FFI), the family of origin scale (FOS), and dyadic adjustment scale (DAS).

NEO-five factor inventory (NEO-FFI)

The NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) is a revised version of Costa and McCrae’s NEO personality inventory [22]. This questionnaire has a short form called NEO-FFI which has been used in this study. The NEO-FFI [29] is a 60-item self-report instrument used to measure the five personality domains according to the FFM: N, E, O, A, and C (12 items per domain). The NEO-FFI includes self-descriptive statements that participants respond to them using a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert-type scale. Scores for each domain are calculated by summing the 12 item responses with a score from 0 to 48. Costa and McCrae have reported the alpha coefficients of 0.68 (for agreeableness) to 0.86 (for neuroticism) [29].

They also suggested that the shortened version is consistent with the long-form; so that the short-form scales are more than 0.68 correlated with the full version. This explains 85% of the variance in convergent validity. They conducted a 7-year longitudinal study of peer assessment where the test was used and achieved a reliability coefficient between 0.82 to 0.51 for 18 secondary traits of N, E, O, and 0.81 to 0.61 for five main factors. The Cronbach alpha coefficients for each of the main factors of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness were respectively 0.86, 0.73, 0.56, 0.56, and 0.87.

Family of Origin Scale (FOS)

The family of origin scale is a retrospective instrument in which individuals rate the family in which they were raised. Conceptually, the FOS is based upon two overarching constructs-autonomy and intimacy-each of which is represented by five subscales. In this model, a healthy family gives independence to its members through clarity of expression, personal responsibility, respect for the other family members, openness to others in the family, and acceptance of separation and loss. At the same time, the healthy family creates intimacy in family through the expression of a wide range of feelings, creating a warm atmosphere at home, dealing with conflicts without undue stress, promoting sensitivity in family members, and trusting in the goodness of human nature [30].

FOS is a 40-item measure with each item rated on a 1 to 5 Likert-type scale according to the respondent’s level of agreement with each statement (1.strongly disagree; 5. strongly agree) [30]. The highest rating “5” is awarded to an option that is close to health and the lowest rating “1” to an option that is close to a lack of health. The minimum score is 40 and the maximum is 200. Higher scores indicate a better perception of the health of the family of origin.

Traditional psychometric studies consistently found that the FOS was reliable. There was also evidence of discriminant validity with some support for construct validity. Hovestadt et al. in a study on original FOS reported two weeks test-retest reliabilities of 0.97 for the whole scale with a median of 0.77 for the 20 autonomy items and 0.73 for intimacy. The internal consistency, as measured by the Cronbach alpha, was 0.97 [30].

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)

This scale is a tool that is widely used in assessing the compatibility in relationships and is one of the most useful tools in the field of marriage and family [31]. This 32-item Likert-type self-report instrument is used to assess marital relationship quality and measures four aspects of the relationship: dyadic satisfaction, dyadic cohesion, dyadic consensus, and affectional expression. The total score is from 0 to 150 which is obtained by summing the scores of questions. Some questions should be reversed for scoring [32].

The scale is of considerable internal consistency. Carey, Spector, Lantinga, and Krauss in examining the validity of this scale, achieved high internal consistency (0.95) [33]. Spanier reported the validity of the scale as 0.96. He also reported the concurrent validity of the scale as 0.86 based on correlation with Locke and Wallace’s marital adjustment questionnaire [34].

3. Results

The data were analyzed using structural equation modeling procedures and bootstrap testing.

Descriptive statistics for study variables

In table 1, the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum amount of study variables (the health of the family of origin, five personality traits, and marital adjustment) are reported.

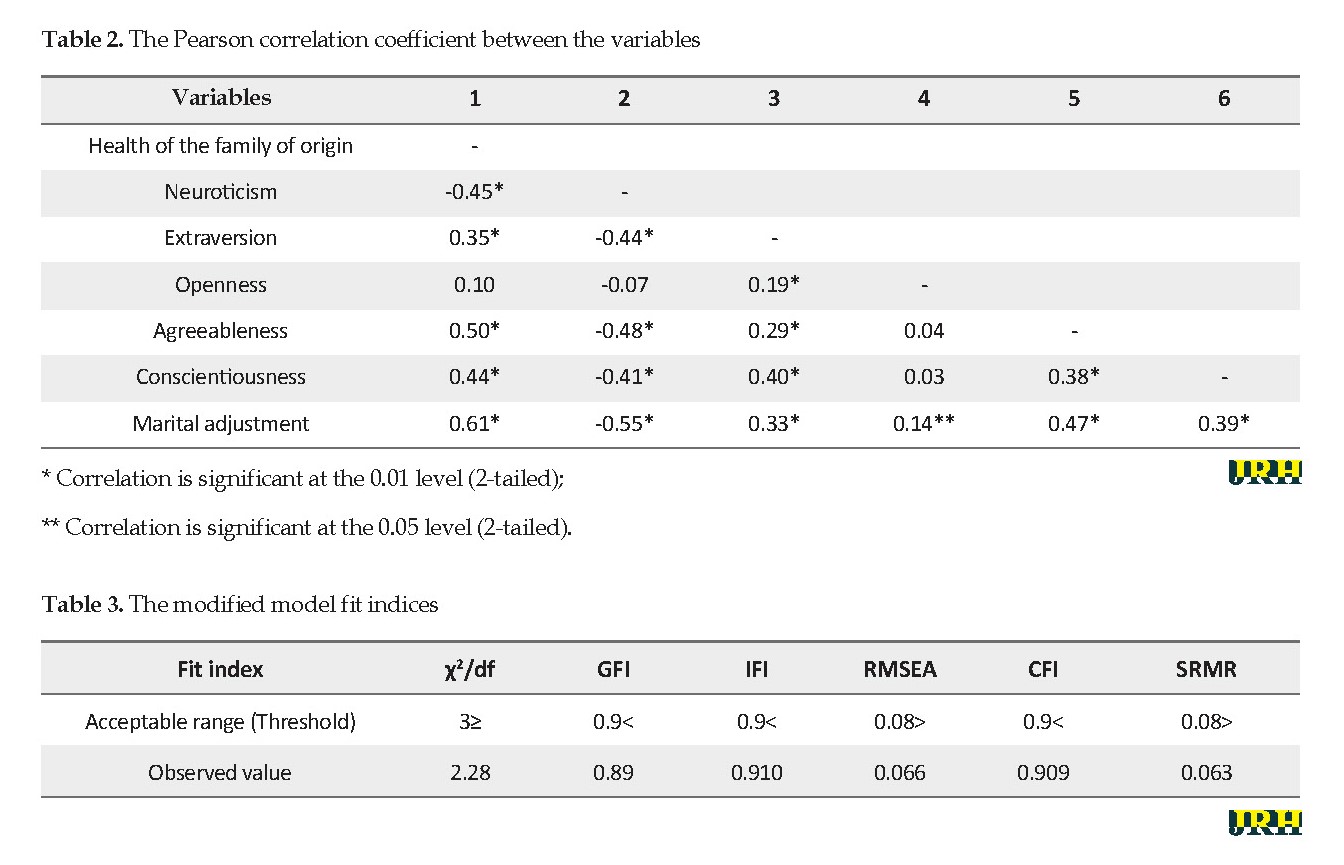

As shown in Table 2, given that in the components openness to experience and health of the family of origin, the correlation is significant at the 0.05 level, the relationship (correlation) between the two variables is not significant. But the health of the family of origin has a significant negative relationship with neuroticism and a significant positive relationship with agreeableness, conscientiousness, and marital adjustment.

Marital adjustment is significantly correlated with five personality factors and the relationship with neuroticism is negative.

Marital adjustment is significantly correlated with five personality factors and the relationship with neuroticism is negative.

Assumptions of the structural equation modeling

The assumptions of structural equation modeling in this study are as follows: common method bias, outliers, multicollinearity, multivariate normality, linear relationship between the observed variables and their constructs and between one construct and another, no missing data, and unidimensionality of constructs.

The assumptions of structural equation modeling in this study are as follows: common method bias, outliers, multicollinearity, multivariate normality, linear relationship between the observed variables and their constructs and between one construct and another, no missing data, and unidimensionality of constructs.

Structural equation modeling findings

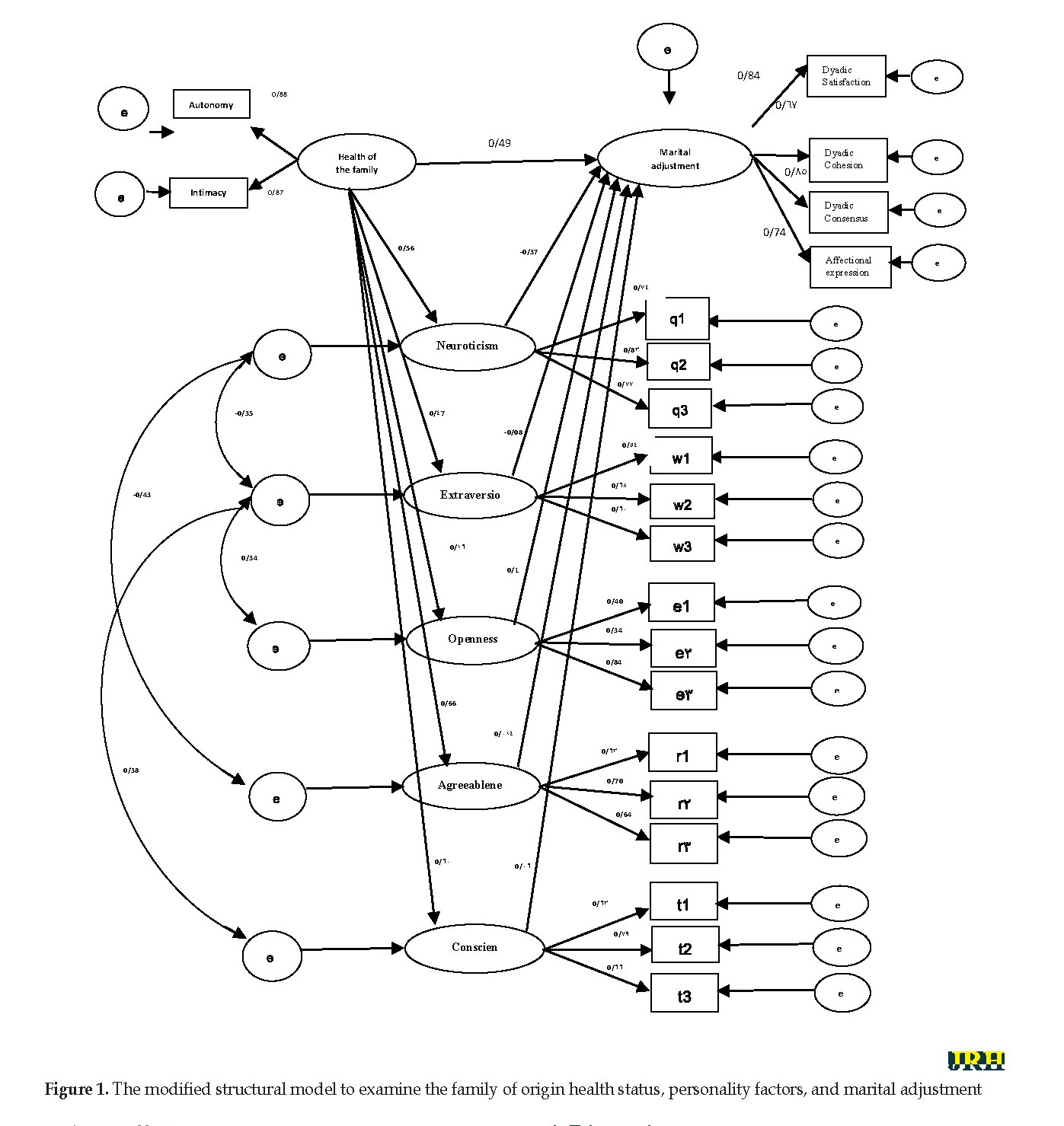

To determine the conceptual model, structural equation modeling was used in the AMOS software. In the following, we present the structural model and indices related to the fit. The presented model was evaluated using the item parceling method. Using item parceling rather than the individual questions results in enhancing indices validity, reducing the number of estimated parameters, creating markers with an almost normal distribution, and improving the model’s fit. In this study, indices of personality factors were formed through the random division of each factor’s question into 3 groups and adding up the scores of each group’s questions. Based on the questions related to each factor, 3 items were created for each of them. According to the 12 questions, 3-question packages were created for each personality factor. Due to the inappropriate fit indices, namely, GFI, IFI, and CFI that are lower than the acceptable threshold (0.9), the model has been modified and the final version is given below.

To determine the conceptual model, structural equation modeling was used in the AMOS software. In the following, we present the structural model and indices related to the fit. The presented model was evaluated using the item parceling method. Using item parceling rather than the individual questions results in enhancing indices validity, reducing the number of estimated parameters, creating markers with an almost normal distribution, and improving the model’s fit. In this study, indices of personality factors were formed through the random division of each factor’s question into 3 groups and adding up the scores of each group’s questions. Based on the questions related to each factor, 3 items were created for each of them. According to the 12 questions, 3-question packages were created for each personality factor. Due to the inappropriate fit indices, namely, GFI, IFI, and CFI that are lower than the acceptable threshold (0.9), the model has been modified and the final version is given below.

In Figure 1, the standardized coefficients of the modified structural model are shown. To improve the fit index, the covariance between some components of personality factors error is included in the model. Overall, regarding the total calculated fit indices, it can be said that the model fits the data well.

The normed Chi-square (χ2/df) confirms the model fit. In other words, it is less than 3 and indicates the model fit (χ2/df ≥ 3). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.066 and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) is 0.063 which are both lower (smaller) than the criterion (0.08) and low compared to the original model. Also, compared to the original model, IFI, CFI, and GFI increased that are all larger than the criterion (0.9). Overall, regarding the total calculated fit indices, the model fits the data well (Table 3).

Indirect effect

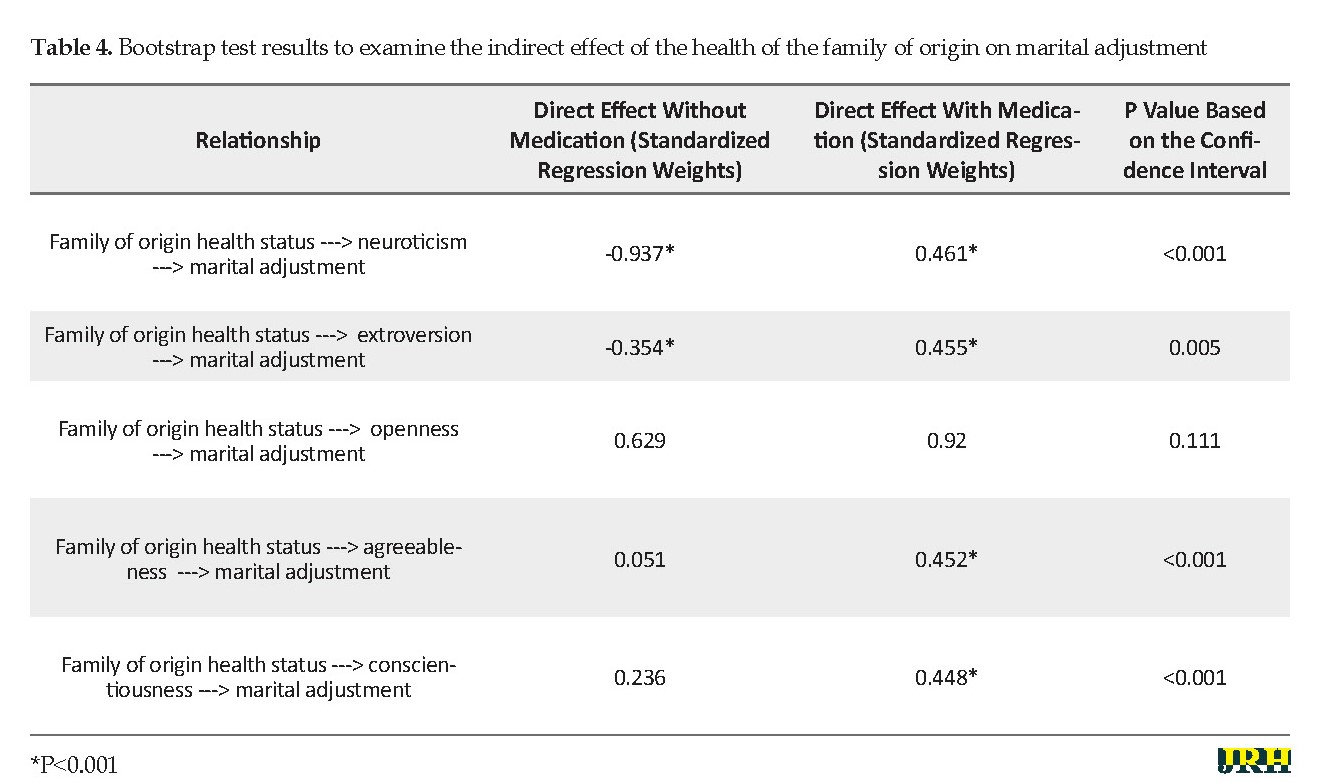

In the bootstrap method, the default model (with a mediator) and direct model (only direct effect) are compared. Based on the empirical 95% confidence interval, as shown in Table 4, the health of the family of origin indirectly affects marital adjustment through the four personality factors of neuroticism, extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, at a significance level of less than 0.05. But the factor openness has no role in the relationship between the health of the family of origin and marital adjustment.

4. Discussion

The structural equation modeling and total calculated fit indices have approved the model’s fit. Also, in addition to the direct impact of the health of the family of origin on marital adjustment, bootstrap test results showed that the health of the family of origin indirectly affects marital adjustment through personality factors of neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and consciousness.

The fitted conceptual model of the present study is consistent with the DEARR model (The development of early adult romantic relationships model). The model proposes that a set of characteristics in the family of origin will, over time, influence the competence of a child in early adult romantic relationships. The model predicts that family of origin experiences will influence attributes of the early adult couple relationship either directly or indirectly through (a) early adult socioeconomic circumstances and (b) individual attributes of a young adult. The model also hypothesizes that family of origin experiences may directly affect couples’ relationships and then, these characteristics predict success in adulthood relationships [34].

Overall, the findings showed that some personality factors indirectly play a role in the relationship between the health of the family of origin with marital adjustment and assume some part of the influence on marital adjustment. These findings are in agreement with the findings of Habibi, Haji Heydari, and Darharaj [35], who confirmed the role of personality problems as one of the three main reasons for divorce in Iran.

The health of the family of origin affects marital adjustment partly through neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and consciousness. These characteristics are some of the factors that affect marital life and marital adjustment (compatibility with a partner) through the effects of the family of origin. Focusing on couple relationships highlights the role of the family as an environment in which people spent the most hours of life [36].

5. Conclusion

These results emphasize the importance of the family of origin and also identifying personality factors, because the family of origin experiences and individual’s personality may be associated with higher or lower levels of marital adjustment. These factors play a crucial role in reducing marital conflicts and increasing compatibility in marital life. Therefore, understanding the determinant variables that influence marital adjustment can help prevent problems and promote community health because various studies indicate that marital adjustment will affect the individual and social aspects of human life. Marital adjustment facilitates parental roles [37], increases the duration of marital relationship [38], improves couples’ health [39], and increases life satisfaction in couples [40].

In general, marital adjustment is a multi-dimensional concept that includes various factors that contribute to satisfaction or dissatisfaction in this relationship [34]. Increasing knowledge in this field provides helpful hints for therapists working in the field of family and marriage counseling.

The present study has some limitations. First, the partner’s characteristics should be noted as it could be involved in marital adjustment as well as an individual’s features. However, this issue was not considered in this study. Second, considering restrictions for the cooperation and participation of the participants, we used the available sampling method. In this method, findings cannot be generalized with certainty to all members of society. It is recommended that future research study couples (instead of choosing married men and women) and their health from their original family and its role in the marital relationship. The difference in the method of measuring research variables may also cause different results; therefore, the use of other measuring methods, such as questionnaires or observation and interview methods are recommended. Also, more serious attention should be paid to qualitative research on the family of origin and its effects on couples’ relationships.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was part of the Master thesis at Shahid Beheshti University in 2016. The Ethics Committee of the Family Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University (Code: 27148- Date: 2015/6/9) approved the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the contribution of all study subjects and research staff who kindly helped us during the development of research.

Refrences

Larson JH & Holman TB. Premarital predictors of marital quality and stability. Family Relations Fam. Relat. Premarital Predictors of Marital Quality and Stability 1994; 43(2):228-37. [DOI:10.2307/585327]

Stoeber J. Dyadic perfectionism in romantic relationships: Predicting relationship satisfaction and longterm commitment. Personality and Individual Differences. Pers Individ Dif. 2012; 53(3):300-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.002]

Bali A, Dhingra R, Baru A. Marital adjustment of childless couples. Soc Sci J. 2010; 24(1):73-6. [DOI:10.1080/09718923.2010.11892839]

Greeff A. Characteristics of families that function well. J Fam Issues. 2000; 21(8):948-62. [DOI:10.1177/019251300021008001]

Whitton SW, Waldinger RJ, Schulz MS, Allen JP, Crowell JA, Hauser ST. Prospective associations from family-of-origin interactions to adult marital interactions and relationship adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2008; 22(2):274-86. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.274] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dinero RE, Conger RD, Shaver PR, Widaman KF, Larsen-Rife D. Influence of family of origin and adult romantic partners on romantic attachment security. J Fam Psychol. 2008; 22(4):622-32. [DOI:10.1037/a0012506] [PMID] [PMCID]

Davies PT, Lindsay LL. Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: Why does gender moderate early adolescent vulnerability? J Fam Psychol. 2004; 18(1):160-70. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.160] [PMID]

Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987; 52(3):511-24. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511] [PMID]

Sanaei B. The role of family of origin in children marriage. J Couns Dev. 1999; 1(2):21-6. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=20075

Dennison RP, Koerner SS, Segrin C. A dyadic examination of family-of-origin influence on newlyweds’ marital satisfaction. J Fam Psychol. 2014; 28(3):429-35. [DOI:10.1037/a0036807] [PMID]

Johnson MD, Nguyen L, Anderson JR, Liu W, Vennum A. Pathways to romantic relationship success among Chinese young adult couples: Contributions of family dysfunction, mental health problems, and negative couple interaction. J Soc Pers Relat. 2015; 32(1):5-23. [DOI:10.1177/0265407514522899]

Falcke D, Wagner A, Mosmann CP. The relationship between family-of-origin and marital adjustment for couples in Brazil. J Fam Psychother. 2008; 19(2):170-86. [DOI:10.1080/08975350801905020]

Story LB, Karney BR, Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Interpersonal mediators in the intergenerational transmission of marital dysfunction. J Fam Psychol. 2004; 18(3):519-29. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.519] [PMID]

Muraru AA, Turliuc MN. Family-of-origin, romantic attachment, and marital adjustment: a path analysis model. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012; 33:90-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.089]

Muraru AA, Turliuc MN. Predictors of marital adjustment: Are there any differences between women and men? Eur J Psychol. 2013; 9(3):427-42. [DOI:10.5964/ejop.v9i3.524]

Ghoroghi S, Hassan SA, Baba M. Function of Family-of-Origin experiences and marital adjustment among married Iranian students of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Int J Psychol Stud. 2012; 4(3):94. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v4n3p94]

Solomon BC, Jackson JJ. Why do personality traits predict divorce? Multiple pathways through satisfaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014; 106(6):978-96. [DOI:10.1037/a0036190] [PMID]

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. United States: Guilford Press; 2003. [DOI:10.4324/9780203428412]

Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990; 58(4):644-63. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644] [PMID]

Headey B, Wearing AJ. Chains of well-being. Paper Presented at the International Sociological Association conference. August 1986; New Delhi, India.

Headey B, Veenhoven R, Weari A. Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Soc Indic Res. 1991; 16:81–100. [DOI:10.1007/BF00292652]

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: happy and unhappy people. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980; 38(4):668-78. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668] [PMID]

Luo S, Klohnen EC. Assortative mating and marital quality in newlyweds: a couple-centered approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005; 88(2):304-26. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.304] [PMID]

Anderson JR, Johnson MD, Liu W, Zheng F, Hardy NR, Lindstrom RA. Young adult romantic relationships in Mainland China: Perceptions of family of origin functioning are directly and indirectly associated with relationship success. J Soc Pers Relat. 2014; 31(7):871-87. [DOI:10.1177/0265407513508727]

Rauer AJ, Volling BL. The role of husbands’ and wives’ emotional expressivity in the marital relationship. Sex roles. 2005; 52(9-10):577-87. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-005-3726-6]

Watson D, Hubbard B, Wiese D. General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self‐and partner‐ratings. J Personal. 2000; 68(3):413-49. [DOI:10.1111/1467-6494.00102] [PMID]

Shackelford TK, Buss DM. Marital satisfaction and spousal cost-infliction. Pers Individ Dif. 2000; 28(5):917-28. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00150-6]

Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Costa Jr PT, McCrae RR. The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R). Boyle GJ, Matthews G, Saklofske DH editors. The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment. California: Sage Publications Inc; 2008.

Hovestadt AJ, Anderson WT, Piercy FP, Cochran SW, Fine M. A family‐of‐origin scale. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985; 11(3):287-97. [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00621.x]

Spanier GB, Thompson L. A confirmatory analysis of the dyadic adjustment scale. J Marriage Fam. 1982: 731-8. [DOI:10.2307/351593]

Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976: 15-28. [DOI:10.2307/350547]

Carey MP, Spector IP, Lantinga LJ, Krauss DJ. Reliability of the dyadic adjustment scale Psychol Assess. 1993; 5(2):238. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.238]

Bryant CM, Conger RD. An Intergenerational Model of Romantic. Stab Chang Relatsh. 2002: 57-82. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511499876.005] [PMID]

Habibi M, Hajiheydari Z, Darharaj M. Causes of divorce in the marriage phase from the viewpoint of couples referred to Iran’s family courts. J Divorce Remarriage. 2015; 56(1):43-56. [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2014.972195]

Sabatelli RM, Bartle‐Haring S. Family‐of‐origin experiences and adjustment in married couples. J Marriage Fam. 2003; 65(1):159-69. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00159.x]

Mackey RA, O’Brien BA. Marital conflict management: Gender and ethnic differences. Soc Work. 1998; 43(2):128-41. [DOI:10.1093/sw/43.2.128]

Nakonezny PA, Shull RD, Rodgers JL. The effect of no-fault divorce law on the divorce rate across the 50 states and its relation to income, education, and religiosity. J Marriage Fam. 1995: 477-88. [DOI:10.2307/353700]

Demo DH, Acock AC. Singlehood, marriage, and remarriage: The effects of family structure and family relationships on mothers’ well-being. J Fam Issues. 1996; 17(3):388-407. [DOI:10.1177/019251396017003005]

Nock SL. A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. J Fam Issues. 1995; 16(1):53-76. [DOI:10.1177/019251395016001004]

The normed Chi-square (χ2/df) confirms the model fit. In other words, it is less than 3 and indicates the model fit (χ2/df ≥ 3). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.066 and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) is 0.063 which are both lower (smaller) than the criterion (0.08) and low compared to the original model. Also, compared to the original model, IFI, CFI, and GFI increased that are all larger than the criterion (0.9). Overall, regarding the total calculated fit indices, the model fits the data well (Table 3).

Indirect effect

In the bootstrap method, the default model (with a mediator) and direct model (only direct effect) are compared. Based on the empirical 95% confidence interval, as shown in Table 4, the health of the family of origin indirectly affects marital adjustment through the four personality factors of neuroticism, extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, at a significance level of less than 0.05. But the factor openness has no role in the relationship between the health of the family of origin and marital adjustment.

4. Discussion

The structural equation modeling and total calculated fit indices have approved the model’s fit. Also, in addition to the direct impact of the health of the family of origin on marital adjustment, bootstrap test results showed that the health of the family of origin indirectly affects marital adjustment through personality factors of neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and consciousness.

The fitted conceptual model of the present study is consistent with the DEARR model (The development of early adult romantic relationships model). The model proposes that a set of characteristics in the family of origin will, over time, influence the competence of a child in early adult romantic relationships. The model predicts that family of origin experiences will influence attributes of the early adult couple relationship either directly or indirectly through (a) early adult socioeconomic circumstances and (b) individual attributes of a young adult. The model also hypothesizes that family of origin experiences may directly affect couples’ relationships and then, these characteristics predict success in adulthood relationships [34].

Overall, the findings showed that some personality factors indirectly play a role in the relationship between the health of the family of origin with marital adjustment and assume some part of the influence on marital adjustment. These findings are in agreement with the findings of Habibi, Haji Heydari, and Darharaj [35], who confirmed the role of personality problems as one of the three main reasons for divorce in Iran.

The health of the family of origin affects marital adjustment partly through neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and consciousness. These characteristics are some of the factors that affect marital life and marital adjustment (compatibility with a partner) through the effects of the family of origin. Focusing on couple relationships highlights the role of the family as an environment in which people spent the most hours of life [36].

5. Conclusion

These results emphasize the importance of the family of origin and also identifying personality factors, because the family of origin experiences and individual’s personality may be associated with higher or lower levels of marital adjustment. These factors play a crucial role in reducing marital conflicts and increasing compatibility in marital life. Therefore, understanding the determinant variables that influence marital adjustment can help prevent problems and promote community health because various studies indicate that marital adjustment will affect the individual and social aspects of human life. Marital adjustment facilitates parental roles [37], increases the duration of marital relationship [38], improves couples’ health [39], and increases life satisfaction in couples [40].

In general, marital adjustment is a multi-dimensional concept that includes various factors that contribute to satisfaction or dissatisfaction in this relationship [34]. Increasing knowledge in this field provides helpful hints for therapists working in the field of family and marriage counseling.

The present study has some limitations. First, the partner’s characteristics should be noted as it could be involved in marital adjustment as well as an individual’s features. However, this issue was not considered in this study. Second, considering restrictions for the cooperation and participation of the participants, we used the available sampling method. In this method, findings cannot be generalized with certainty to all members of society. It is recommended that future research study couples (instead of choosing married men and women) and their health from their original family and its role in the marital relationship. The difference in the method of measuring research variables may also cause different results; therefore, the use of other measuring methods, such as questionnaires or observation and interview methods are recommended. Also, more serious attention should be paid to qualitative research on the family of origin and its effects on couples’ relationships.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was part of the Master thesis at Shahid Beheshti University in 2016. The Ethics Committee of the Family Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University (Code: 27148- Date: 2015/6/9) approved the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the contribution of all study subjects and research staff who kindly helped us during the development of research.

Refrences

Larson JH & Holman TB. Premarital predictors of marital quality and stability. Family Relations Fam. Relat. Premarital Predictors of Marital Quality and Stability 1994; 43(2):228-37. [DOI:10.2307/585327]

Stoeber J. Dyadic perfectionism in romantic relationships: Predicting relationship satisfaction and longterm commitment. Personality and Individual Differences. Pers Individ Dif. 2012; 53(3):300-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.002]

Bali A, Dhingra R, Baru A. Marital adjustment of childless couples. Soc Sci J. 2010; 24(1):73-6. [DOI:10.1080/09718923.2010.11892839]

Greeff A. Characteristics of families that function well. J Fam Issues. 2000; 21(8):948-62. [DOI:10.1177/019251300021008001]

Whitton SW, Waldinger RJ, Schulz MS, Allen JP, Crowell JA, Hauser ST. Prospective associations from family-of-origin interactions to adult marital interactions and relationship adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2008; 22(2):274-86. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.274] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dinero RE, Conger RD, Shaver PR, Widaman KF, Larsen-Rife D. Influence of family of origin and adult romantic partners on romantic attachment security. J Fam Psychol. 2008; 22(4):622-32. [DOI:10.1037/a0012506] [PMID] [PMCID]

Davies PT, Lindsay LL. Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: Why does gender moderate early adolescent vulnerability? J Fam Psychol. 2004; 18(1):160-70. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.160] [PMID]

Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987; 52(3):511-24. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511] [PMID]

Sanaei B. The role of family of origin in children marriage. J Couns Dev. 1999; 1(2):21-6. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=20075

Dennison RP, Koerner SS, Segrin C. A dyadic examination of family-of-origin influence on newlyweds’ marital satisfaction. J Fam Psychol. 2014; 28(3):429-35. [DOI:10.1037/a0036807] [PMID]

Johnson MD, Nguyen L, Anderson JR, Liu W, Vennum A. Pathways to romantic relationship success among Chinese young adult couples: Contributions of family dysfunction, mental health problems, and negative couple interaction. J Soc Pers Relat. 2015; 32(1):5-23. [DOI:10.1177/0265407514522899]

Falcke D, Wagner A, Mosmann CP. The relationship between family-of-origin and marital adjustment for couples in Brazil. J Fam Psychother. 2008; 19(2):170-86. [DOI:10.1080/08975350801905020]

Story LB, Karney BR, Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Interpersonal mediators in the intergenerational transmission of marital dysfunction. J Fam Psychol. 2004; 18(3):519-29. [DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.519] [PMID]

Muraru AA, Turliuc MN. Family-of-origin, romantic attachment, and marital adjustment: a path analysis model. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012; 33:90-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.089]

Muraru AA, Turliuc MN. Predictors of marital adjustment: Are there any differences between women and men? Eur J Psychol. 2013; 9(3):427-42. [DOI:10.5964/ejop.v9i3.524]

Ghoroghi S, Hassan SA, Baba M. Function of Family-of-Origin experiences and marital adjustment among married Iranian students of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Int J Psychol Stud. 2012; 4(3):94. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v4n3p94]

Solomon BC, Jackson JJ. Why do personality traits predict divorce? Multiple pathways through satisfaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014; 106(6):978-96. [DOI:10.1037/a0036190] [PMID]

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. United States: Guilford Press; 2003. [DOI:10.4324/9780203428412]

Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990; 58(4):644-63. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644] [PMID]

Headey B, Wearing AJ. Chains of well-being. Paper Presented at the International Sociological Association conference. August 1986; New Delhi, India.

Headey B, Veenhoven R, Weari A. Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Soc Indic Res. 1991; 16:81–100. [DOI:10.1007/BF00292652]

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: happy and unhappy people. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980; 38(4):668-78. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668] [PMID]

Luo S, Klohnen EC. Assortative mating and marital quality in newlyweds: a couple-centered approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005; 88(2):304-26. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.304] [PMID]

Anderson JR, Johnson MD, Liu W, Zheng F, Hardy NR, Lindstrom RA. Young adult romantic relationships in Mainland China: Perceptions of family of origin functioning are directly and indirectly associated with relationship success. J Soc Pers Relat. 2014; 31(7):871-87. [DOI:10.1177/0265407513508727]

Rauer AJ, Volling BL. The role of husbands’ and wives’ emotional expressivity in the marital relationship. Sex roles. 2005; 52(9-10):577-87. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-005-3726-6]

Watson D, Hubbard B, Wiese D. General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self‐and partner‐ratings. J Personal. 2000; 68(3):413-49. [DOI:10.1111/1467-6494.00102] [PMID]

Shackelford TK, Buss DM. Marital satisfaction and spousal cost-infliction. Pers Individ Dif. 2000; 28(5):917-28. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00150-6]

Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Costa Jr PT, McCrae RR. The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R). Boyle GJ, Matthews G, Saklofske DH editors. The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment. California: Sage Publications Inc; 2008.

Hovestadt AJ, Anderson WT, Piercy FP, Cochran SW, Fine M. A family‐of‐origin scale. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985; 11(3):287-97. [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00621.x]

Spanier GB, Thompson L. A confirmatory analysis of the dyadic adjustment scale. J Marriage Fam. 1982: 731-8. [DOI:10.2307/351593]

Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976: 15-28. [DOI:10.2307/350547]

Carey MP, Spector IP, Lantinga LJ, Krauss DJ. Reliability of the dyadic adjustment scale Psychol Assess. 1993; 5(2):238. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.238]

Bryant CM, Conger RD. An Intergenerational Model of Romantic. Stab Chang Relatsh. 2002: 57-82. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511499876.005] [PMID]

Habibi M, Hajiheydari Z, Darharaj M. Causes of divorce in the marriage phase from the viewpoint of couples referred to Iran’s family courts. J Divorce Remarriage. 2015; 56(1):43-56. [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2014.972195]

Sabatelli RM, Bartle‐Haring S. Family‐of‐origin experiences and adjustment in married couples. J Marriage Fam. 2003; 65(1):159-69. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00159.x]

Mackey RA, O’Brien BA. Marital conflict management: Gender and ethnic differences. Soc Work. 1998; 43(2):128-41. [DOI:10.1093/sw/43.2.128]

Nakonezny PA, Shull RD, Rodgers JL. The effect of no-fault divorce law on the divorce rate across the 50 states and its relation to income, education, and religiosity. J Marriage Fam. 1995: 477-88. [DOI:10.2307/353700]

Demo DH, Acock AC. Singlehood, marriage, and remarriage: The effects of family structure and family relationships on mothers’ well-being. J Fam Issues. 1996; 17(3):388-407. [DOI:10.1177/019251396017003005]

Nock SL. A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. J Fam Issues. 1995; 16(1):53-76. [DOI:10.1177/019251395016001004]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2018/03/23 | Accepted: 2020/06/12 | Published: 2020/06/12

Received: 2018/03/23 | Accepted: 2020/06/12 | Published: 2020/06/12

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |