Volume 15, Issue 4 (Jul & Aug 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(4): 321-332 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ravaghi H, Nakhaee M, Seyedin H, Khayyeri F. Agenda-setting Analysis for Health Literacy Promotion Using Kingdon’s Model: A Descriptive-comparative Study. J Research Health 2025; 15 (4) :321-332

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2414-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2414-en.html

1- School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt.

2- School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran. ,m.nakhae@gmail.com

3- School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Miwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran. ,

3- School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Miwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 893 kb]

(451 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2945 Views)

Full-Text: (456 Views)

Introduction

In recent decades, health literacy has become a significant issue on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) agenda. In the Shanghai Health Promotion Declaration, the Organization made a strong and serious commitment for all countries worldwide to policymaking on health literacy as one of the three pillars of achieving sustainable development goals and health equity. These thematic pillars included good governance, healthy cities, and health literacy [1, 2]. In recent years, health literacy has been recognized as one of the most critical determinants of health and has drawn the attention of researchers, policymakers and stakeholders worldwide. In 2004, a report titled “Health Literacy, a prescription for the end of confusion,” by the Institute of Medicine of America, identified health literacy as one of the most critical issues requiring more attention in decision-making and policymaking [3]. Evidence shows that inadequate health literacy is associated with harmful health outcomes and more use of health care services. It is identified as one of the most essential factors in creating inequalities in using services and the community’s level of health [4]. In addition, health literacy being introduced as an individual and social capital in the health field can lead to greater control over people’s health, family, and community, as well as individual, social and environmental determinants of health [5].

In Iran, many studies in the past years have investigated the status of health literacy and the factors affecting it in different groups of Iranian society. These studies show that about 70% of people in society have limited or marginal levels of health literacy and emphasize the need to pay attention to the issue. Based on the findings of these studies, the level of education, family income, demographic indicators including age and gender, and place of residence were among the most critical factors affecting the level of health literacy [6, 7].

Paying attention to the ability of individuals and communities to understand health information and make informed decisions can significantly affect people’s health and improve the performance of health care systems. Still, it has been consistently neglected by policymakers [8]. Given the importance of health literacy to public health and for policymakers, it is essential to understand health literacy, interventions and policies to promote it. To our knowledge, no study has specifically examined health literacy policies in a comparative study format. Our findings can help clarify some dimensions and potential interventions to improve health literacy and provide reliable evidence for other professionals and stakeholders. So, this analytical study explores the agenda-setting process of health literacy in selected countries using Kingdon’s multiple streams model.

Conceptual framework

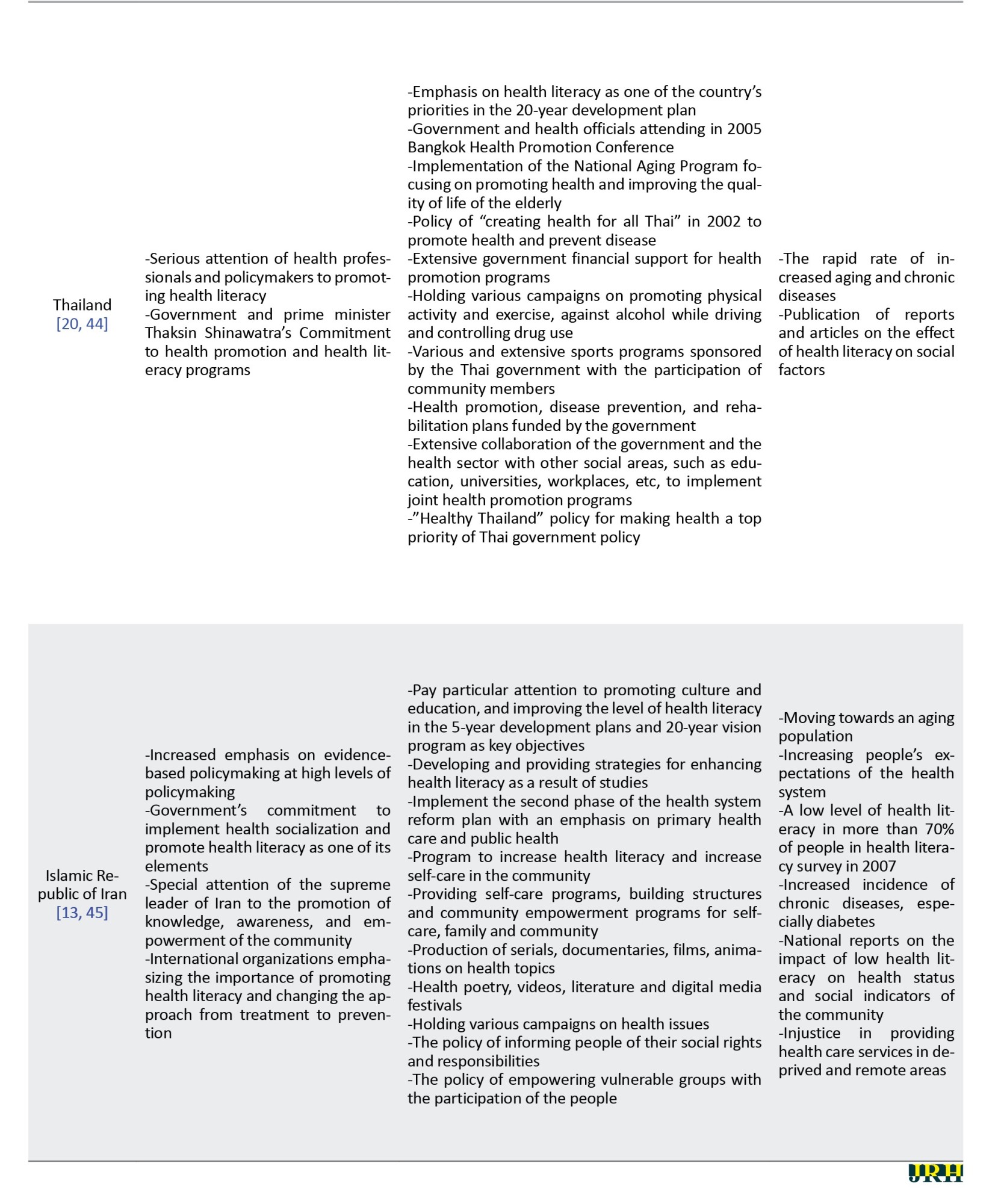

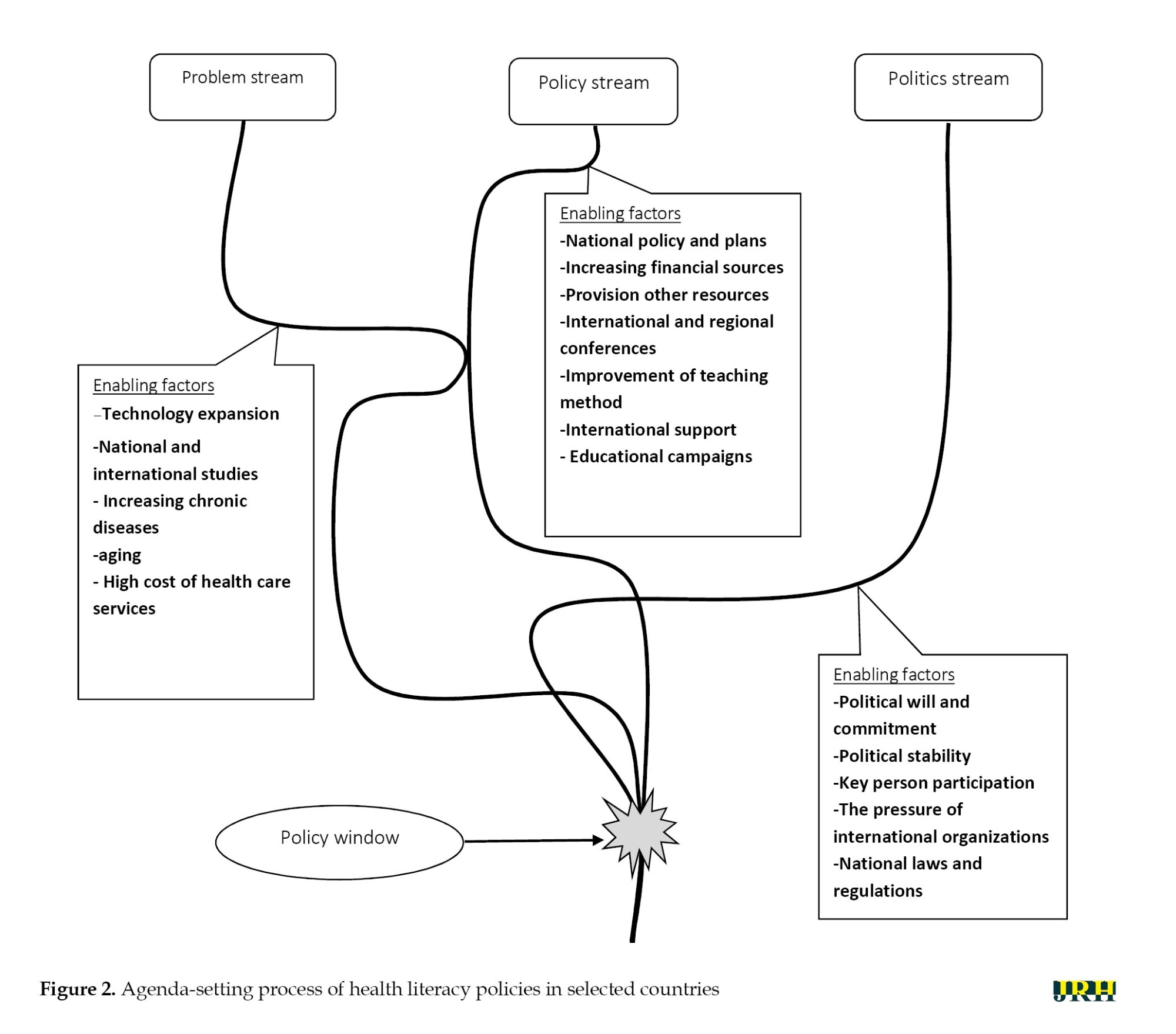

Policy analysis is a concept that covers a wide range of topics, and the purpose may be to examine the content of the policy or to address the policy process. Policy analysis is performed prospectively and retrospectively, helps identify and overcome defects in previous processes, and selects the right paths for future policy making [9]. Agenda setting as the first stage of the policymaking process is an essential part of policy analysis, during which an issue gets the policymaker’s attention and rises to the agenda at local, national, regional and international levels. One of the primary and significant models in agenda-setting analysis is Kingdon’s multiple streams model [10], in which a policy emerges on the formal agenda when three streams of problem, policy, and politics converge [11].

The problem stream refers to issues faced by policymakers. Statistical indicators, policy reports, and pressure from advocacy groups usually draw policymakers’ attention to the problem. The policy stream describes a set of proposals and solutions developed for a situation. Finally, the politics stream indicates how national and international climate and social pressure influence whether or not an issue emerges on the agenda. According to Kingdon, these three streams’ interaction, synergy, and connection lead to the emergence and formation of policies [12]. According to this model, triple streams move in different, independent directions for a given time, and at a certain point, called the “policy windows,” these streams are combined, and advocacy of policy entrepreneurs is present. At this point, the issues have entered the policymaking agenda (Figure 1). The confluence of these streams and the creation of policy windows are unpredictable and do not follow a specific trend.

Methods

Study design

Based on Kingdon’s multiple streams model, the descriptive-comparative study investigated the agenda-setting process of health literacy policies in seven countries: The USA, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Turkey, Thailand, and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Selection of countries

After an initial search, we selected 7 countries with available policy documents related to health literacy. The final criteria for selecting countries were as follows:

1) Having adequate documents; 2) Availability of documents without restrictions; 3) Geographical distribution and choosing at least one country from each continent

As such, the United States of America, Australia, Thailand, Turkey, Chile, Iran and South Africa were selected.

Data collection

An electronic search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, ISI, Google Scholar, public websites, websites of related international organizations (WHO, World Bank, etc.) and websites of selected countries’ health ministries. Keywords included “health policy,” “policymaking,” “literacy,” “self-care,” “self-management,” and “health literacy.” The search was conducted for each selected country. The required data for conducting this study were gathered by reviewing reliable national and international documents, studies and reports, and the irrelevant documents were excluded.

Data analysis

Agenda setting refers to how a particular issue gains the attention of policymakers amongst other issues competing for priority. Based on Kingdon’s model, policies are shaped by the confluence of problem, policy, and politics streams [12]. To analyze the data, findings from each country were extracted and summarized using the comparative table. The factors involved in agenda setting were evaluated, compared and assessed using the content analysis method.

Results

Problem stream

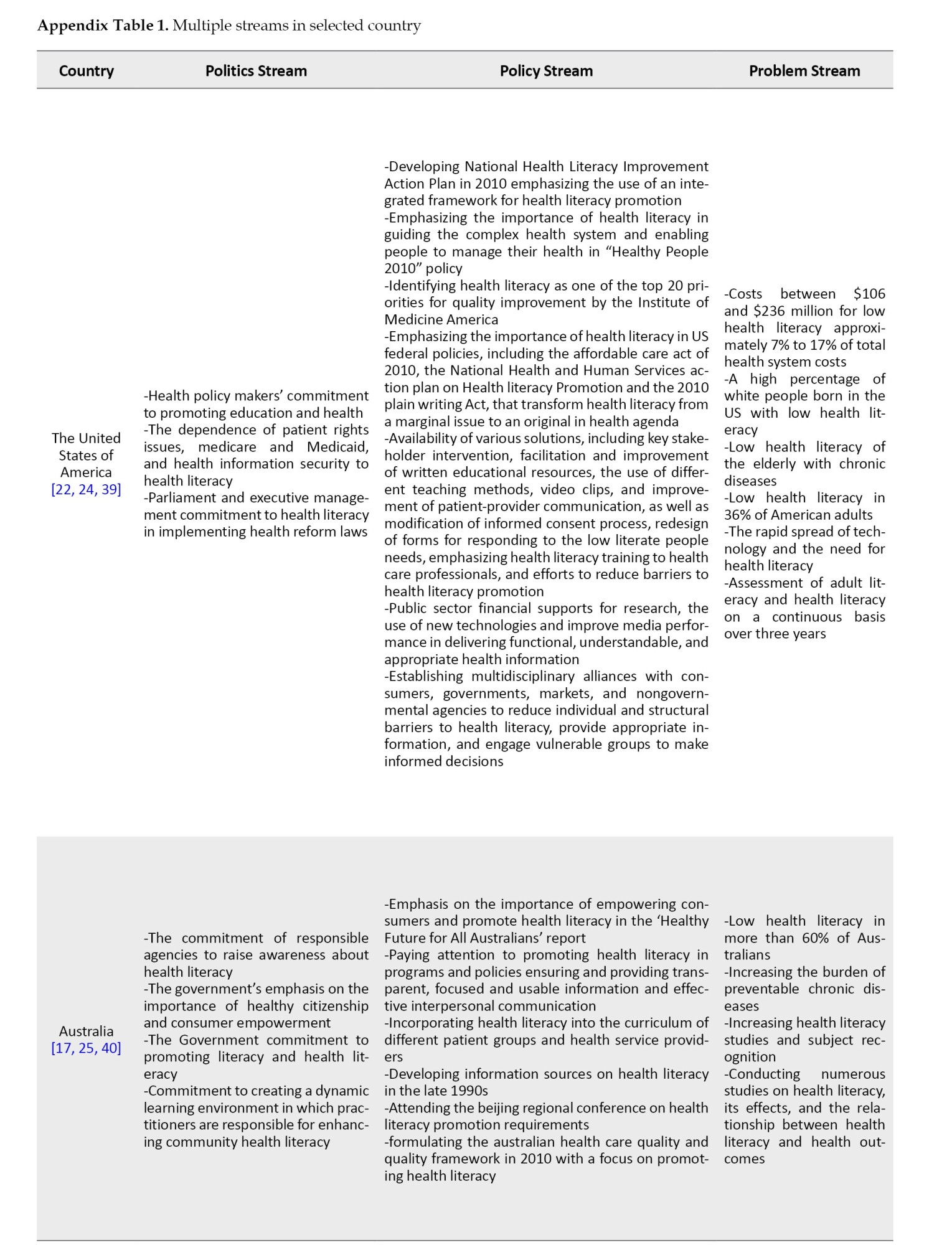

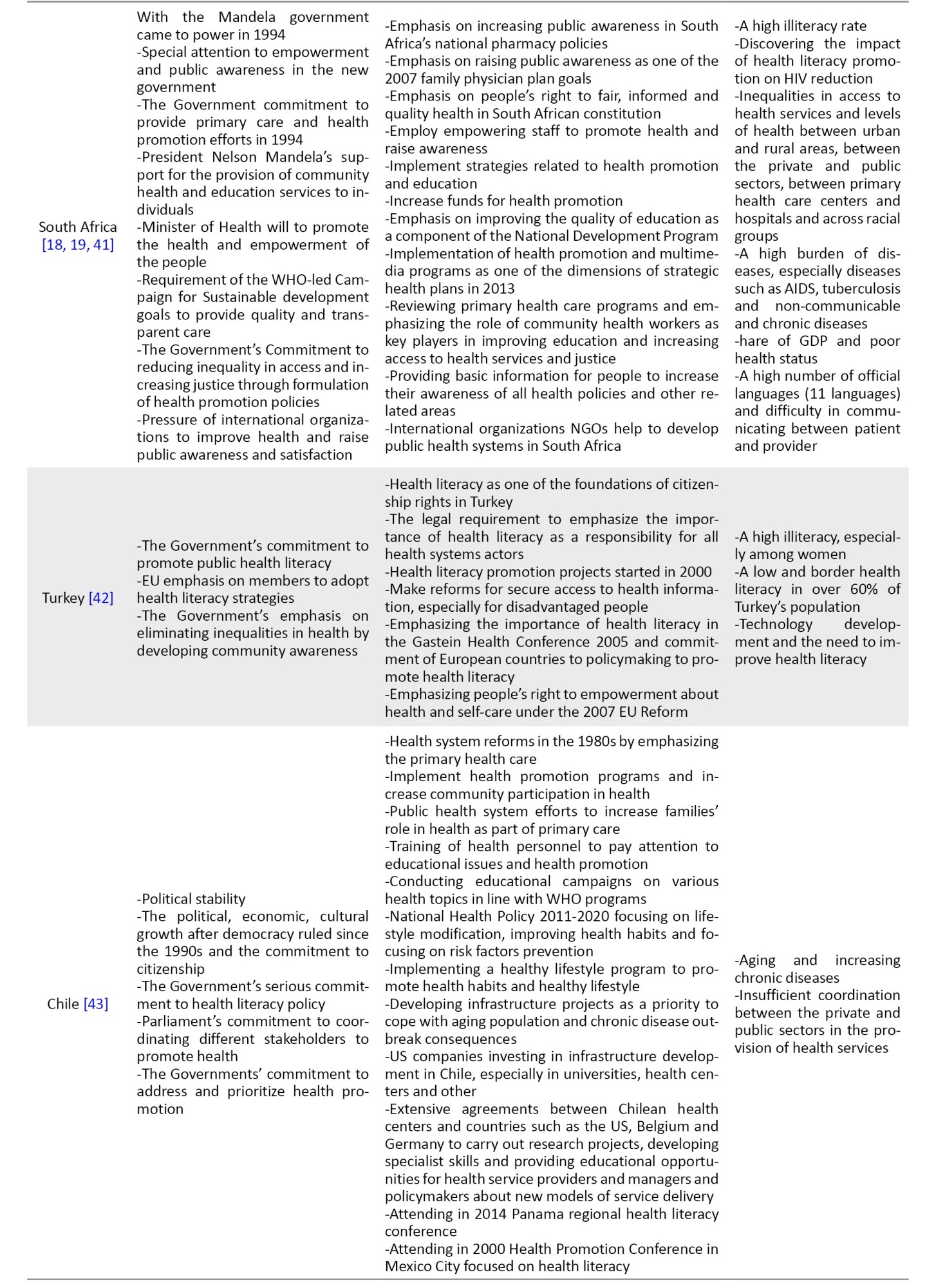

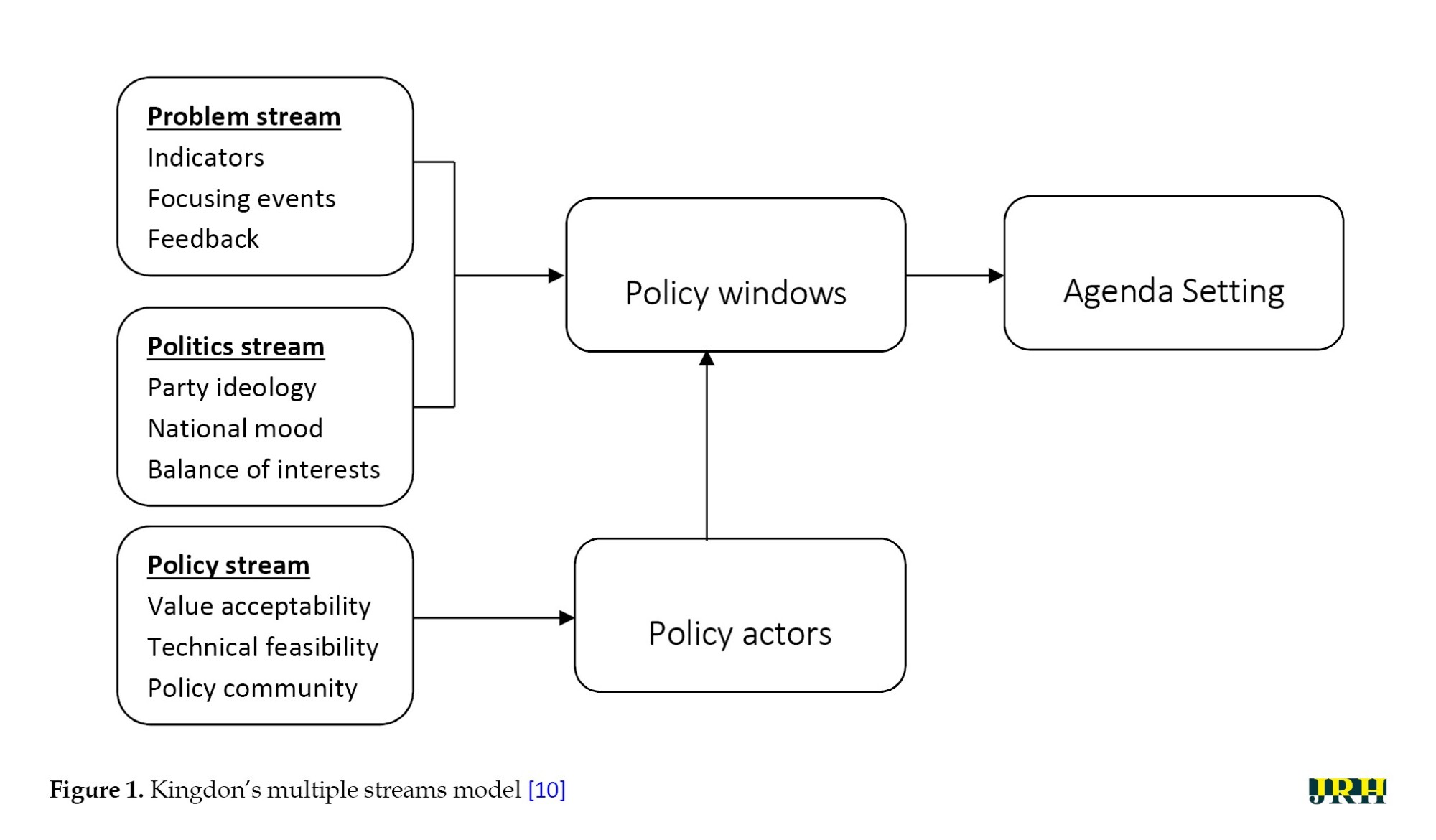

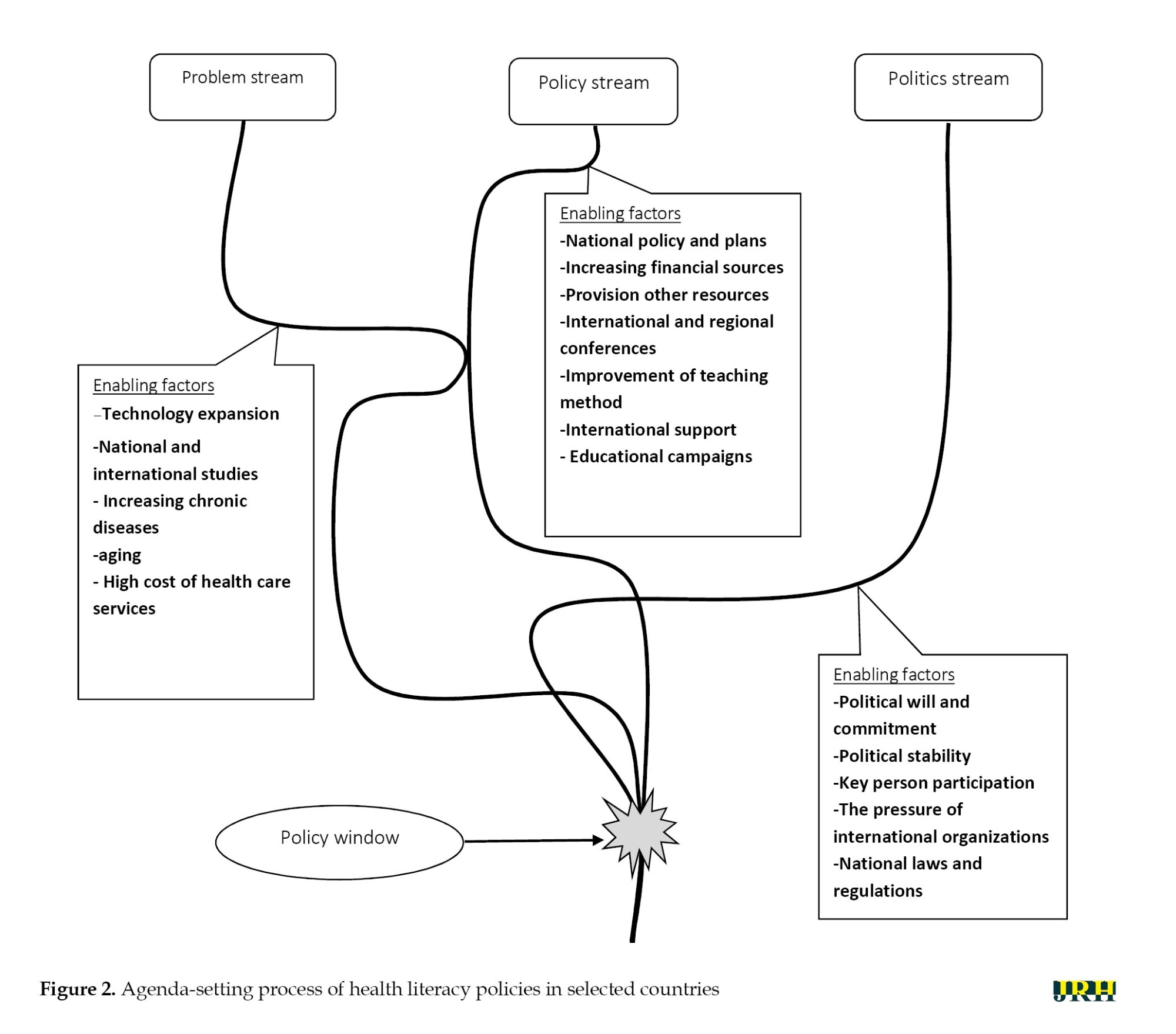

According to its effects on health, health care, costs, and the health status of society, health literacy is one of the main determinants of health and it has posed a major challenge since its emergence. Health literacy has always been a key issue in the health systems of the selected countries and increasing non-communicable diseases, rising health care costs, and changing disease patterns have made health literacy more important. Publishing reports on health literacy at various international, national, regional, and local conferences has also played an important role in highlighting the problem. Also, the measurement of health literacy level and its influencing factors in the studied countries, such as Iran [7, 13], Turkey [14], the USA [15], Australia [16] and South Africa [17, 18], shows the severity of the issue. These studies report very low levels of health literacy in these countries, and the WHO reports indicate that health literacy levels in most countries are low [2, 20]. At the academic level, health literacy is also rapidly expanding, with many international conferences focusing on the various aspects of health literacy in recent years that have helped highlight the problem stream [17] (Appendix 1).

Policy stream

To understand and assess the policy stream in this study, technical feasibility, financial and technical support at national and international levels, and formulating and presenting national and local programs were considered driver factors. Almost all countries have benefited from technical support from international organizations, especially the WHO and its regional offices, given the WHO’s emphasis on promoting health literacy and people-centered care. The findings of this study indicate that issues related to health literacy, its importance, promotion strategies and challenges have been repeatedly highlighted in national, local, regional, and international conferences. Health literacy was a requirement for all countries in the Shanghai Declaration. Holding conferences and meetings at various levels, receiving support from international organizations, charities, and NGOs in the technical, operational and financial aspects, and developing strategic and operational plans are the most important enabling factors mentioned in the policy stream. [2, 20, 21] Countries also take numerous but diffuse measures to promote health literacy; some countries, such as the USA [22], Australia, and, to some extent, the Islamic Republic of Iran, have developed specific policies to promote health literacy. Also, increasing the financial resources and qualitative and quantitative strengthening of the human resources in health promotion and health literacy have been widely included in the programs and conducts of countries (Appendix 1).

Politics stream

This study evaluated the policymakers’ will and commitment, key person participation, involvement of influential and responsible organizations, the general public’s demand, regulation and the political situation for shaping the politics stream. All selected countries have been relatively politically stable in recent years. One of the main forces in bringing health literacy into the policy agenda in all countries has been the international requirements, especially the WHO’s emphasis on this issue. In the USA, Australia, Turkey and South Africa, the government has played the most serious role in raising the issue of health literacy. Also, people’s expectations and awareness of their rights, governments, and related organizations are more actively engaged in upholding citizenship and community awareness. The main factors that highlight the policy stream are the involvement, support, and participation of key persons, national health authorities and officials in national and international conferences focusing on promoting health and health literacy. Attendance of Thai Prime Minister and Health Managers at Bangkok and Shanghai Conferences, Chilean Health Officials at Panama and Mexico City conferences and support for public awareness raising plans, turkish health managers attending multiple conferences on health literacy at the European level and a large number of international and regional conferences attended by country officials, are instances of their attention to health literacy decisions and policies. In addition, the strong support from the Thai Prime Minister for promoting health literacy and the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran were other examples of serious attention to health literacy in Thailand and Iran (Appendix 1).

Opening the policy window

According to Kingdon’s model, the three streams acted separately to integrate at a specific point, called the policy window. At this time, the policy window has been opened and policymakers are taking the matter seriously. This study showed that various factors and events in different countries have contributed to integrating streams and opening the window. In almost all countries, especially Iran, the USA, Australia, South Africa and Turkey, the main driving force in opening the policy window was highlighting the problem. Conducting research projects and disseminating the findings of various studies on the level of health literacy and the economic and social consequences of lower levels of health literacy were the primary causes of increased attention and deeper investigation. Health literacy is designated a research priority in the United States, extensive research is conducted, supportive coalitions are formed in more than 20 states and the federal government’s special focus and commitment have opened the policy window [23, 24]. The Australian quality and safety commission for health care collected data on health literacy in Australia between 2011 and 2012. At the same time, state-level programs were also implemented that helped bolster the streams and open the policy window [17]. Support from international organizations such as UNESCO, the WHO and American companies, participation in the panama regional health literacy conference and conducting research projects by the United States, Belgium and Germany reinforces the policy stream and opens Chile’s policy window [25]. In South Africa, the reign of democracy since 1994 and political stability, increased burden of chronic diseases, and a serious commitment to promoting community knowledge and literacy have strengthened the political stream and opened the window of policy [17, 26]. The European Health Association conference Gastein (2016) and the emphasis of EU health officials on the need for policymaking on health literacy and the commitment of national health authorities to member states have been key factors in opening the policy window in Turkey. [27]. In Thailand, the Prime Minister’s participation in the Bangkok Health Promotion Conference and the emphasis on health literacy promotion were key factors in opening the policy window (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this study, the agenda-setting process of health literacy was analyzed in seven selected countries. One of the most important factors in raising the health literacy agenda was increasing research and generating needed evidence. Those studies facilitated health literacy agenda setting in two dimensions: First, highlighting the problem stream through determining the severity of the problem and its impact on other health determinants in communities, and second, identifying the challenges facing health literacy promotion and introducing health literacy strategies.

Problem stream

One of the basic and primary requirements for a health-related issue to enter the policy agenda is policymakers’ access to reliable and valuable evidence [28]. Our finding shows that health literacy has always been an important issue in various forms. Still, more attention has been needed in recent years due to the changing pattern of diseases, the increase in chronic diseases, and the population’s aging. In addition, the need to pay attention to self-care has dramatically increased medical costs, raised people’s expectations, and led to more sophisticated therapies. In several selected countries, the published reports on health literacy status and low health literacy level highlighted the problem stream and opened the policy window [29]. Also, the role of health literacy in reducing costs and promoting health has made policymakers consider it a cheap and effective solution [30].

Politics stream

In the current study, the political stability, the will and desire of governments and national authorities, the commitment of health policymakers, and the requirements by international organizations and institutions for promoting health literacy were the most important factors shaping the politics stream in all selected countries. The political instability affects the inclusion of issues on the agenda. In this regard, Nutbeam et al. mentioned the Australian elections in the 1990s, when an election was held despite a problem stream and a lack of support evidence and codified national goals. The health minister who supported this issue did not survive the election and was not included on the agenda then [31]. Support from key people and senior leaders contributing to the development of policies is considered one of the most important factors in enhancing the political stream [32]. The prime minister’s focus on health literacy programs and measures and the supreme leader’s statements on empowering people and increasing health literacy were the most important factors that enhanced the politics stream in Thailand and Iran, respectively. Finally, as societies become more aware, public expectations over citizens’ rights are increasing from government and so; governments look more closely at issues of community empowerment. There is also much experience in other countries in supporting these ideas that political stability and policymakers will strengthen politics stream [33, 34].

Policy stream

Policy stream refers to solutions and policy options to solve issues and problems [12]. Based on the results, international organizations’ technical and financial support in various dimensions, including providing guidelines, tools and financial support, are the most important factors influencing the policy stream. Some other studies have also mentioned the effect of international support in the technical and financial dimensions in strengthening the policy stream [35, 36]. According to studies, presenting national public health policy bills, developing national strategies, public health and policy documents and international guidance were factors that have helped strengthen the politics stream in health policy areas around the world [37, 38]. Also, over the past few decades, numerous national, regional, and international conferences have been held focusing on the issue of health literacy as one of the key tools for promoting health, and commitments made at these conferences have facilitated health literacy policymaking in countries. European :union: (EU) high-level pharmaceutical forum in 2008, a meeting of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in 2009, the Vilnius meeting and a political declaration of the high-level meeting of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in 2011 are examples of these meetings where similar actions have been taken at national levels [17, 34]. Formulating and presenting innovative programs can draw the attention of policymakers to the issue [34]. In the current study, almost all countries held some forms of these programs, such as various campaigns, educational programs, film and serial production, advertisements and rising health staff knowledge and skills. The findings of this study show that specific policies have been designed to promote health literacy in Australia and the USA. In Iran, this issue has been highlighted and mentioned in some policies in recent years. The other measures were to increase public sector financial support for health literacy programs, pay more attention to research projects, attract key stakeholders in the health, education, and other sectors, and use new educational technologies.

Finally, it should be noted that creating discourse at the community level and increasing awareness of various aspects of health literacy have a major impact on highlighting the issue and raising the problem stream. Also, support from the masses and elites, the generation, and the use of evidence lead to convincing executives and policymakers to address this issue. At the same time, raising the problem in the academic environment has led to increased studies and a better understanding of the subject, as well as the presentation of various solutions and policy proposals to different environmental conditions, and enhancing the policy stream. All these events eventually led to joining the three streams and opening the window of opportunity.

Conclusion

Policy theories are useful tools for accurate and realistic analysis, correct understanding, and microscopic review of agenda setting, formulation, and implementation of policies.

Health literacy, as one of the new issues in the field of health, was initially placed on the agenda due to the requirements created by international organizations and the inclusion of issues in these organizations’ agendas. The expansion of studies on health literacy, the low level of health literacy, the serious commitment of governments and domestic policymakers and the existence of national programs and policies were other common features among almost all selected countries.

According to Kingdon’s model, the policy stream, politics stream and problem stream must confluence at one point and form a policy window. The findings show that the activity of these three streams cannot be considered separately; that is, the activity of one stream greatly enhances the others. Based on our findings, activities such as producing and disseminating the evidence that caused the emergence of the problem stream have played an important role in leading to the open policy window, and it has influenced the simultaneous operation of the three streams.

Contrary to Kingdon’s view, the findings of this study show that the three streams may interact at different times and strengthen or weaken each other. In addition, this model is silent about the role of entrepreneurs in opening or using the policy window and has kept this issue ambiguous.

Finally, based on the findings of this study, we suggest that to facilitate the inclusion of health literacy on the agenda, programs should be designed to expand targeted and community-based studies to strengthen the problem and policy streams, as well as efforts to encourage influential individuals and politicians to intervene in this field. Also, Kingdon’s multiple streams model has been useful in the health literacy agenda-setting process, so it is recommended to be used to analyze other policies, especially in the health field.

Study limitations

The main challenges in collecting and extracting data for shaping three streams were the lack of comprehensive and sufficient studies and documentation on some countries, especially Chile and Thailand, and the publication of reports and articles in Spanish and Portuguese on Chile.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IUMS.REC 1395.9221557207) and performed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Majid Nakhaee, approved by the Department of Health Management and Information Science, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Hamid Ravaghi and Majid Nakhaee; Investigation and software: Majid Nakhaee; Supervision: Hamid Ravaghi; Writing and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appriciate the support of School of Health Management, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

In recent decades, health literacy has become a significant issue on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) agenda. In the Shanghai Health Promotion Declaration, the Organization made a strong and serious commitment for all countries worldwide to policymaking on health literacy as one of the three pillars of achieving sustainable development goals and health equity. These thematic pillars included good governance, healthy cities, and health literacy [1, 2]. In recent years, health literacy has been recognized as one of the most critical determinants of health and has drawn the attention of researchers, policymakers and stakeholders worldwide. In 2004, a report titled “Health Literacy, a prescription for the end of confusion,” by the Institute of Medicine of America, identified health literacy as one of the most critical issues requiring more attention in decision-making and policymaking [3]. Evidence shows that inadequate health literacy is associated with harmful health outcomes and more use of health care services. It is identified as one of the most essential factors in creating inequalities in using services and the community’s level of health [4]. In addition, health literacy being introduced as an individual and social capital in the health field can lead to greater control over people’s health, family, and community, as well as individual, social and environmental determinants of health [5].

In Iran, many studies in the past years have investigated the status of health literacy and the factors affecting it in different groups of Iranian society. These studies show that about 70% of people in society have limited or marginal levels of health literacy and emphasize the need to pay attention to the issue. Based on the findings of these studies, the level of education, family income, demographic indicators including age and gender, and place of residence were among the most critical factors affecting the level of health literacy [6, 7].

Paying attention to the ability of individuals and communities to understand health information and make informed decisions can significantly affect people’s health and improve the performance of health care systems. Still, it has been consistently neglected by policymakers [8]. Given the importance of health literacy to public health and for policymakers, it is essential to understand health literacy, interventions and policies to promote it. To our knowledge, no study has specifically examined health literacy policies in a comparative study format. Our findings can help clarify some dimensions and potential interventions to improve health literacy and provide reliable evidence for other professionals and stakeholders. So, this analytical study explores the agenda-setting process of health literacy in selected countries using Kingdon’s multiple streams model.

Conceptual framework

Policy analysis is a concept that covers a wide range of topics, and the purpose may be to examine the content of the policy or to address the policy process. Policy analysis is performed prospectively and retrospectively, helps identify and overcome defects in previous processes, and selects the right paths for future policy making [9]. Agenda setting as the first stage of the policymaking process is an essential part of policy analysis, during which an issue gets the policymaker’s attention and rises to the agenda at local, national, regional and international levels. One of the primary and significant models in agenda-setting analysis is Kingdon’s multiple streams model [10], in which a policy emerges on the formal agenda when three streams of problem, policy, and politics converge [11].

The problem stream refers to issues faced by policymakers. Statistical indicators, policy reports, and pressure from advocacy groups usually draw policymakers’ attention to the problem. The policy stream describes a set of proposals and solutions developed for a situation. Finally, the politics stream indicates how national and international climate and social pressure influence whether or not an issue emerges on the agenda. According to Kingdon, these three streams’ interaction, synergy, and connection lead to the emergence and formation of policies [12]. According to this model, triple streams move in different, independent directions for a given time, and at a certain point, called the “policy windows,” these streams are combined, and advocacy of policy entrepreneurs is present. At this point, the issues have entered the policymaking agenda (Figure 1). The confluence of these streams and the creation of policy windows are unpredictable and do not follow a specific trend.

Methods

Study design

Based on Kingdon’s multiple streams model, the descriptive-comparative study investigated the agenda-setting process of health literacy policies in seven countries: The USA, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Turkey, Thailand, and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Selection of countries

After an initial search, we selected 7 countries with available policy documents related to health literacy. The final criteria for selecting countries were as follows:

1) Having adequate documents; 2) Availability of documents without restrictions; 3) Geographical distribution and choosing at least one country from each continent

As such, the United States of America, Australia, Thailand, Turkey, Chile, Iran and South Africa were selected.

Data collection

An electronic search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, ISI, Google Scholar, public websites, websites of related international organizations (WHO, World Bank, etc.) and websites of selected countries’ health ministries. Keywords included “health policy,” “policymaking,” “literacy,” “self-care,” “self-management,” and “health literacy.” The search was conducted for each selected country. The required data for conducting this study were gathered by reviewing reliable national and international documents, studies and reports, and the irrelevant documents were excluded.

Data analysis

Agenda setting refers to how a particular issue gains the attention of policymakers amongst other issues competing for priority. Based on Kingdon’s model, policies are shaped by the confluence of problem, policy, and politics streams [12]. To analyze the data, findings from each country were extracted and summarized using the comparative table. The factors involved in agenda setting were evaluated, compared and assessed using the content analysis method.

Results

Problem stream

According to its effects on health, health care, costs, and the health status of society, health literacy is one of the main determinants of health and it has posed a major challenge since its emergence. Health literacy has always been a key issue in the health systems of the selected countries and increasing non-communicable diseases, rising health care costs, and changing disease patterns have made health literacy more important. Publishing reports on health literacy at various international, national, regional, and local conferences has also played an important role in highlighting the problem. Also, the measurement of health literacy level and its influencing factors in the studied countries, such as Iran [7, 13], Turkey [14], the USA [15], Australia [16] and South Africa [17, 18], shows the severity of the issue. These studies report very low levels of health literacy in these countries, and the WHO reports indicate that health literacy levels in most countries are low [2, 20]. At the academic level, health literacy is also rapidly expanding, with many international conferences focusing on the various aspects of health literacy in recent years that have helped highlight the problem stream [17] (Appendix 1).

Policy stream

To understand and assess the policy stream in this study, technical feasibility, financial and technical support at national and international levels, and formulating and presenting national and local programs were considered driver factors. Almost all countries have benefited from technical support from international organizations, especially the WHO and its regional offices, given the WHO’s emphasis on promoting health literacy and people-centered care. The findings of this study indicate that issues related to health literacy, its importance, promotion strategies and challenges have been repeatedly highlighted in national, local, regional, and international conferences. Health literacy was a requirement for all countries in the Shanghai Declaration. Holding conferences and meetings at various levels, receiving support from international organizations, charities, and NGOs in the technical, operational and financial aspects, and developing strategic and operational plans are the most important enabling factors mentioned in the policy stream. [2, 20, 21] Countries also take numerous but diffuse measures to promote health literacy; some countries, such as the USA [22], Australia, and, to some extent, the Islamic Republic of Iran, have developed specific policies to promote health literacy. Also, increasing the financial resources and qualitative and quantitative strengthening of the human resources in health promotion and health literacy have been widely included in the programs and conducts of countries (Appendix 1).

Politics stream

This study evaluated the policymakers’ will and commitment, key person participation, involvement of influential and responsible organizations, the general public’s demand, regulation and the political situation for shaping the politics stream. All selected countries have been relatively politically stable in recent years. One of the main forces in bringing health literacy into the policy agenda in all countries has been the international requirements, especially the WHO’s emphasis on this issue. In the USA, Australia, Turkey and South Africa, the government has played the most serious role in raising the issue of health literacy. Also, people’s expectations and awareness of their rights, governments, and related organizations are more actively engaged in upholding citizenship and community awareness. The main factors that highlight the policy stream are the involvement, support, and participation of key persons, national health authorities and officials in national and international conferences focusing on promoting health and health literacy. Attendance of Thai Prime Minister and Health Managers at Bangkok and Shanghai Conferences, Chilean Health Officials at Panama and Mexico City conferences and support for public awareness raising plans, turkish health managers attending multiple conferences on health literacy at the European level and a large number of international and regional conferences attended by country officials, are instances of their attention to health literacy decisions and policies. In addition, the strong support from the Thai Prime Minister for promoting health literacy and the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran were other examples of serious attention to health literacy in Thailand and Iran (Appendix 1).

Opening the policy window

According to Kingdon’s model, the three streams acted separately to integrate at a specific point, called the policy window. At this time, the policy window has been opened and policymakers are taking the matter seriously. This study showed that various factors and events in different countries have contributed to integrating streams and opening the window. In almost all countries, especially Iran, the USA, Australia, South Africa and Turkey, the main driving force in opening the policy window was highlighting the problem. Conducting research projects and disseminating the findings of various studies on the level of health literacy and the economic and social consequences of lower levels of health literacy were the primary causes of increased attention and deeper investigation. Health literacy is designated a research priority in the United States, extensive research is conducted, supportive coalitions are formed in more than 20 states and the federal government’s special focus and commitment have opened the policy window [23, 24]. The Australian quality and safety commission for health care collected data on health literacy in Australia between 2011 and 2012. At the same time, state-level programs were also implemented that helped bolster the streams and open the policy window [17]. Support from international organizations such as UNESCO, the WHO and American companies, participation in the panama regional health literacy conference and conducting research projects by the United States, Belgium and Germany reinforces the policy stream and opens Chile’s policy window [25]. In South Africa, the reign of democracy since 1994 and political stability, increased burden of chronic diseases, and a serious commitment to promoting community knowledge and literacy have strengthened the political stream and opened the window of policy [17, 26]. The European Health Association conference Gastein (2016) and the emphasis of EU health officials on the need for policymaking on health literacy and the commitment of national health authorities to member states have been key factors in opening the policy window in Turkey. [27]. In Thailand, the Prime Minister’s participation in the Bangkok Health Promotion Conference and the emphasis on health literacy promotion were key factors in opening the policy window (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this study, the agenda-setting process of health literacy was analyzed in seven selected countries. One of the most important factors in raising the health literacy agenda was increasing research and generating needed evidence. Those studies facilitated health literacy agenda setting in two dimensions: First, highlighting the problem stream through determining the severity of the problem and its impact on other health determinants in communities, and second, identifying the challenges facing health literacy promotion and introducing health literacy strategies.

Problem stream

One of the basic and primary requirements for a health-related issue to enter the policy agenda is policymakers’ access to reliable and valuable evidence [28]. Our finding shows that health literacy has always been an important issue in various forms. Still, more attention has been needed in recent years due to the changing pattern of diseases, the increase in chronic diseases, and the population’s aging. In addition, the need to pay attention to self-care has dramatically increased medical costs, raised people’s expectations, and led to more sophisticated therapies. In several selected countries, the published reports on health literacy status and low health literacy level highlighted the problem stream and opened the policy window [29]. Also, the role of health literacy in reducing costs and promoting health has made policymakers consider it a cheap and effective solution [30].

Politics stream

In the current study, the political stability, the will and desire of governments and national authorities, the commitment of health policymakers, and the requirements by international organizations and institutions for promoting health literacy were the most important factors shaping the politics stream in all selected countries. The political instability affects the inclusion of issues on the agenda. In this regard, Nutbeam et al. mentioned the Australian elections in the 1990s, when an election was held despite a problem stream and a lack of support evidence and codified national goals. The health minister who supported this issue did not survive the election and was not included on the agenda then [31]. Support from key people and senior leaders contributing to the development of policies is considered one of the most important factors in enhancing the political stream [32]. The prime minister’s focus on health literacy programs and measures and the supreme leader’s statements on empowering people and increasing health literacy were the most important factors that enhanced the politics stream in Thailand and Iran, respectively. Finally, as societies become more aware, public expectations over citizens’ rights are increasing from government and so; governments look more closely at issues of community empowerment. There is also much experience in other countries in supporting these ideas that political stability and policymakers will strengthen politics stream [33, 34].

Policy stream

Policy stream refers to solutions and policy options to solve issues and problems [12]. Based on the results, international organizations’ technical and financial support in various dimensions, including providing guidelines, tools and financial support, are the most important factors influencing the policy stream. Some other studies have also mentioned the effect of international support in the technical and financial dimensions in strengthening the policy stream [35, 36]. According to studies, presenting national public health policy bills, developing national strategies, public health and policy documents and international guidance were factors that have helped strengthen the politics stream in health policy areas around the world [37, 38]. Also, over the past few decades, numerous national, regional, and international conferences have been held focusing on the issue of health literacy as one of the key tools for promoting health, and commitments made at these conferences have facilitated health literacy policymaking in countries. European :union: (EU) high-level pharmaceutical forum in 2008, a meeting of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in 2009, the Vilnius meeting and a political declaration of the high-level meeting of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in 2011 are examples of these meetings where similar actions have been taken at national levels [17, 34]. Formulating and presenting innovative programs can draw the attention of policymakers to the issue [34]. In the current study, almost all countries held some forms of these programs, such as various campaigns, educational programs, film and serial production, advertisements and rising health staff knowledge and skills. The findings of this study show that specific policies have been designed to promote health literacy in Australia and the USA. In Iran, this issue has been highlighted and mentioned in some policies in recent years. The other measures were to increase public sector financial support for health literacy programs, pay more attention to research projects, attract key stakeholders in the health, education, and other sectors, and use new educational technologies.

Finally, it should be noted that creating discourse at the community level and increasing awareness of various aspects of health literacy have a major impact on highlighting the issue and raising the problem stream. Also, support from the masses and elites, the generation, and the use of evidence lead to convincing executives and policymakers to address this issue. At the same time, raising the problem in the academic environment has led to increased studies and a better understanding of the subject, as well as the presentation of various solutions and policy proposals to different environmental conditions, and enhancing the policy stream. All these events eventually led to joining the three streams and opening the window of opportunity.

Conclusion

Policy theories are useful tools for accurate and realistic analysis, correct understanding, and microscopic review of agenda setting, formulation, and implementation of policies.

Health literacy, as one of the new issues in the field of health, was initially placed on the agenda due to the requirements created by international organizations and the inclusion of issues in these organizations’ agendas. The expansion of studies on health literacy, the low level of health literacy, the serious commitment of governments and domestic policymakers and the existence of national programs and policies were other common features among almost all selected countries.

According to Kingdon’s model, the policy stream, politics stream and problem stream must confluence at one point and form a policy window. The findings show that the activity of these three streams cannot be considered separately; that is, the activity of one stream greatly enhances the others. Based on our findings, activities such as producing and disseminating the evidence that caused the emergence of the problem stream have played an important role in leading to the open policy window, and it has influenced the simultaneous operation of the three streams.

Contrary to Kingdon’s view, the findings of this study show that the three streams may interact at different times and strengthen or weaken each other. In addition, this model is silent about the role of entrepreneurs in opening or using the policy window and has kept this issue ambiguous.

Finally, based on the findings of this study, we suggest that to facilitate the inclusion of health literacy on the agenda, programs should be designed to expand targeted and community-based studies to strengthen the problem and policy streams, as well as efforts to encourage influential individuals and politicians to intervene in this field. Also, Kingdon’s multiple streams model has been useful in the health literacy agenda-setting process, so it is recommended to be used to analyze other policies, especially in the health field.

Study limitations

The main challenges in collecting and extracting data for shaping three streams were the lack of comprehensive and sufficient studies and documentation on some countries, especially Chile and Thailand, and the publication of reports and articles in Spanish and Portuguese on Chile.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IUMS.REC 1395.9221557207) and performed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Majid Nakhaee, approved by the Department of Health Management and Information Science, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Hamid Ravaghi and Majid Nakhaee; Investigation and software: Majid Nakhaee; Supervision: Hamid Ravaghi; Writing and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appriciate the support of School of Health Management, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Trezona A, Rowlands G, Nutbeam D. Progress in implementing national policies and strategies for health literacy-what have we learned so far? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(7):1554. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15071554] [PMID] [PMCID]

- World Health Organization. Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Health Promotion International. 2017; 32(1):7-8. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daw103] [PMID]

- Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2004. [PMID]

- Pappadis MR, Sander AM, Juengst SB, Leon-Novelo L, Ngan E, Bell KR, et al. The relationship of health literacy to health outcomes among individuals with traumatic brain injury: A traumatic brain injury model systems study. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2024; 39(2):103-14. [DOI:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000912] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Swartz T, Jehan F, Tang A, Gries L, Zeeshan M, Kulvatunyou N, et al. Prospective evaluation of low health literacy and its impact on outcomes in trauma patients. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2018; 85(1):187-92. [DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000001914] [PMID]

- Tavakoly Sany SB, Doosti H, Mahdizadeh M, Orooji A, Peyman N. The health literacy status and its role in interventions in Iran: A systematic and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4260. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18084260] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tavousi M, Haeri MA, Rafiefar S, Solimanian A, Sarbandi F, Ardestani M, et al. [Health literacy in Iran: Findings from a national study (Persian)]. Payesh. 2016; 15(1):95-102. [Link]

- Tassi A. The Emergence of Health Literacy as a Public Policy Priority, Literacy Harvest. Health Literacy, Fall. 2004; 2(1):5-10. [Link]

- Collins T. Health policy analysis: A simple tool for policy makers. Public Health. 2005; 119(3):192-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.03.006] [PMID]

- Kingdon J. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (2nd Ed.). London: Longman; 1995. [Link]

- Walt G, Gilson L. Can frameworks inform knowledge about health policy processes? Reviewing health policy papers on agenda setting and testing them against a specific priority-setting framework. Health Policy and Planning. 2014; 29(Suppl 3):iii6-22. [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czu081] [PMID]

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making health policy. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012. [Link]

- Tehrani Banihashemi SA, Haghdoost AA, Amirkhani MA, Alavian SM, Asgharifard H, Baradaran H, et al. Health literacy and the influencing factors: A study in five provinces of Iran. Strides in Development of Medical Education. 2007; 4(1):1-9. [Link]

- Demirbag B, Koçaslan S, Koçak Z, Şahbazoğlu M, Ateş T. Health literacy status of the patients’ informal caregivers; turkey example. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare Management. 2018; 1(1):1-9. [Link]

- Health UDo, Services H. America’s health literacy: Why we need accessible health information. An issue brief from the US Department of Health and Human Services. Tübingen: Health UDo, Services H; 2008. [Link]

- Bush RA, Boyle FM, Ostini R. Risks associated with low functional health literacy in Australian population. Comment. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2010; 192(8):479. [DOI:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03597.x] [PMID]

- Roundtable on Health Literacy; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: Improving health, health systems, and health policy around the world: Workshop summary. Washington: National Academies Press; 2013. [PMID]

- The Conversation. South Africa’s universal health care plan falls short of fixing an ailing system [Internet]. 2018 [28 June 2018]. Available from: [Link]

- Gray A, Vawda Y. Health legislation and policy. In: Rispel LC, Padarath A, editors. South African health review 2018. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2018. [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Bangkok charter for health promotion in a globalized world. Health Promotion International. 2008; 23(S1):10-24. [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health literacy. The solid facts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Link]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington DC: 2010. [Link]

- Health Literacy. Health literacy activities by state United states [Internet]. 2024 [16 October 2024]. Available from: [Link]

- APHA. Health literacy: Confronting a national public health problem [Internet]. 2010 [9 November 2010]. Available from: [Link]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Health literacy: Taking action to improve safety and quality. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2014. [Link]

- Gray A, Vawda Y. Health policy and legislation. South African Health Review. 2017; 2017(1):13-24. [Link]

- European Health Forum Gastein (EHFG). 19TH European Health Forum Gastein Demographics & Diversity in Europe New Solutions for Health. Vienna; 2016. [Link]

- Kabiri N, Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Khoshbaten M, Arab-Zozani M, Janati A. Gastrointestinal cancer prevention policies in Iran: A policy analysis of agenda-setting using Kingdon's multiple streams. Journal of Cancer Policy. 2021; 27:100265. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcpo.2020.100265] [PMID]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. 2011; (199):1-941. [PMID]

- Haun JN, Patel NR, French DD, Campbell RR, Bradham DD, Lapcevic WA. Association between health literacy and medical care costs in an integrated healthcare system: A regional population based study. BMC Health Services Research. 2015; 15:249. [DOI:10.1186/s12913-015-0887-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Nutbeam D, Wise M. Australia: Planning for better health. Opportunities for health promotion through the development of national health goals and targets. Promotion & Education. 1993; Spec No:19-24. [PMID]

- Weissman A, Nguyen TT, Nguyen HT, Mathisen R. The role of the opinion leader research process in informing policy making for improved nutrition: experience and lessons learned in Southeast Asia. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2020; 4(6):nzaa093. [DOI:10.1093/cdn/nzaa093] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Frankish J. 2010-2011: Health literacy scan project [internet]. 2010 [updated 2025 June 10]. Available from: [Link]

- Quaglio G, Sørensen K, Rübig P, Bertinato L, Brand H, Karapiperis T, et al. Accelerating the health literacy agenda in Europe. Health Promotion International. 2017; 32(6):1074-80. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daw028] [PMID]

- Taghizadeh S, Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Farhangi MA. Childhood obesity prevention policies in Iran: a policy analysis of agenda-setting using Kingdon's multiple streams. BMC Pediatrics. 2021; 21(1):250. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-021-02731-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mhazo AT, Maponga CC. Agenda setting for essential medicines policy in sub-Saharan Africa: a retrospective policy analysis using Kingdon's multiple streams model. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2021; 19(1):72. [DOI:10.1186/s12961-021-00724-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bywall KS, Norgren T, Avagnina B, Gonzalez MP, Andersson SW; IDEAHL consortium. Calling for allied efforts to strengthen digital health literacy in Sweden: Perspectives of policy makers. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24(1):2666. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-20174-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Osborne RH, Elmer S, Hawkins M, Cheng CC, Batterham RW, Dias S, et al. Health literacy development is central to the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. BMJ Global Health. 2022; 7(12):e010362. [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010362] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Koh HK, Berwick DM, Clancy CM, Baur C, Brach C, Harris LM, et al. New federal policy initiatives to boost health literacy can help the nation move beyond the cycle of costly 'crisis care'. Health Affairs. 2012; 31(2):434-43. [DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1169] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Peerson A, Saunders M. Health literacy revisited: What do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promotion International. 2009; 24(3):285-96. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/dap014] [PMID]

- Sopitshi Lvn A. Country profile: South Africa: A descriptive overview of the country and health system context including the opportunitities for innovation. South Africa: Bertha Centre For Socail Innovation & Entrepreneurship. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2016.

- Önal HI. Vital decisions: A critical look at health literacy in Turkey. Paper presented at: IFLA WLIC 2014-Lyon-Libraries, Citizens, Societies: Confluence for Knowledge. 16-22 August 2014; Lyon, France. [Link]

- UNESCO. Latin America seeks new paths for health literacy [internet]. 2014 [Updated 2020 October 9]. Available from: [Link]

- de Leeuw E, Tang KC, Beaglehole R. Ottawa to Bangkok--Health promotion's journey from principles to 'glocal' implementation. Health Promotion International. 2006; 21(Suppl 1):1-4. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/dal057] [PMID]

- Lankarani KB, Alavian SM, Peymani P. Health in the Islamic Republic of Iran, challenges and progresses. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2013; 27(1):42-9. [PMID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

● Health Education

Received: 2023/08/28 | Accepted: 2025/03/5 | Published: 2025/07/1

Received: 2023/08/28 | Accepted: 2025/03/5 | Published: 2025/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |