Volume 14, Issue 5 (Sep & Oct 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(5): 439-448 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: CU: RCEC/00480/08/23.

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Giri M, Pathak S, Srivastava S, Mukherjee S. Exploring the Psychosocial Challenges and Strengths of Indigent Adolescents: A Reflexive Thematic Analysis of Counsellor’s Insights. J Research Health 2024; 14 (5) :439-448

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2497-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2497-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, CHRIST University, Delhi, India. , madhu.giri@res.christuniversity.in

2- Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, CHRIST University, Delhi, India.

3- SHSS Sharda University, Greater Noida, India.

2- Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, CHRIST University, Delhi, India.

3- SHSS Sharda University, Greater Noida, India.

Keywords: Indigent adolescents, Psycho-social challenges, Thematic analysis, Individual strengths, Well-being, Mental health

Full-Text [PDF 685 kb]

(367 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1867 Views)

Full-Text: (298 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period of development during which individuals undergo physical changes, navigate social and emotional complexities, make educational decisions, and develop their identities. Unaddressed challenges during this time can lead to mental health issues and social exclusion [1, 2].

The Bronfenbrenner bioecological model highlights how poverty can become a breeding ground for mental health struggles and personality challenges in adolescents. At the close-up level (microsystem), poverty creates an unstable environment characterized by crowded housing, limited access to healthy food, and exposure to parental stress. This can trigger anxiety, insecurity, and concentration problems in teenagers. Moving outward (mesosystem), poverty strains relationships with family, school, and community [3]. The lack of after-school programs, negative peer influences in under-resourced neighborhoods, and strained family dynamics due to financial pressure can all lead to feelings of isolation, lack of support, and lower self-esteem [4]. Beyond the immediate surroundings (exosystem), poverty limits access to resources, like quality healthcare, mental health services, and educational opportunities. This lack of external support can exacerbate existing mental health issues and hinder the development of healthy coping mechanisms. Finally, the broader context (macrosystem) plays a role as well. Societal factors, like poverty itself and policies that perpetuate it, create a sense of hopelessness and powerlessness in adolescents. Discrimination, a lack of affordable housing, and limited job opportunities for parents all contribute to a negative mental state and overall well-being [5]. In conclusion, poverty acts like a constant stressor across all these layers of the Bronfenbrenner model, shaping adolescents’ personalities through limited opportunities and fostering negative experiences that ultimately impact their mental health.

A significant amount of research enables us to understand the various challenges that indigent adolescents (suffering from extreme poverty, synonymous with impoverished) face [6, 7]. There is a substantial gap in addressing the mental health needs of adolescents, particularly those experiencing economic hardships [8]. However, it is noteworthy that despite all the challenges and adversities, this population demonstrates resilience, flexibility, hope, and positive growth. Although there is a scarcity of research focusing on interventions that promote the well-being of indigent adolescents, the World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the importance of enhancing positive traits in adolescents, such ::::as char::::acter strengths, to promote their well-being [8]. Character strengths are positive traits that can be exercised in daily life activities to achieve an authentic sense of well-being, happiness, and flourishing [9]. In-depth studies are needed to explore the unique strengths of disadvantaged youth beyond existing models. This would involve qualitative research with various stakeholders to understand how these teens overcome the challenges of poverty and thrive.

School counselors offer a unique view of disadvantaged teens. They observe firsthand the impact of poverty on anxieties, coping skills, and even mental health. Unlike statistics, counselors go beyond the numbers to understand the teens’ resilience and potential. They bridge the gap between the teens’ experiences and the underlying issues, highlighting both challenges and strengths.

Methods

Aim and objectives

This study aimed to evaluate counselors’ insights into the psycho-social challenges and strengths of disadvantaged adolescents.

Design

Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with counselors using a semi-structured interview guide. The guide, based on the study goals and literature review, covered key areas, like home life, education, and mental health. Open-ended questions and probes were used to explore the challenges and strengths of disadvantaged adolescents. The guide was validated by two experts with extensive experience in counseling and social work with this population.

Procedure

Sample

This study focused on counselors as a key source of information regarding the risk factors and protective strengths of disadvantaged teens. Counselors’ close relationships with these teens allow for unbiased insights into their challenges and resources. This offers a more complete picture than other stakeholders, like teachers, who might have expectations that cloud their judgment. Counselors act as a bridge between the teens’ experiences and a deeper understanding of their needs. They can offer a nuanced viewpoint that acknowledges the obstacles posed by poverty while emphasizing the teenagers’ inner resources and growth potential.

Data collection

Counselors working with at-risk adolescents (in schools and various community day-care centers in the Delhi/NCR region) were approached through a snowball sampling technique. Since traditional sampling methods might overlook counselors embedded within the support network for indigent adolescents, snowball sampling provided a strategic solution. It capitalized on counselors’ connections with other counselors working in social service agencies, schools, and community centers specifically serving underprivileged youth. By relying on counselor referrals, researchers were able to access a pool of participants with demonstrably relevant experience, thereby maintaining credibility and trust.

Inclusion criteria:

1) At least three years of experience in counseling indigent adolescents. This ensures exposure to various issues and allows counselors to develop effective strategies that leverage adolescents’ inherent strengths

2) Proficiency in speaking English

3) Willingness to dedicate at least one hour for the interview

Exclusion criteria

Counselors from residential schools. Their uniform environment would not reveal the impact of poverty and individual strengths in overcoming challenges.

Ethical considerations:

A detailed briefing: Participants were thoroughly briefed about the study’s aims, objectives, and the expected interview duration (approximately 1 hour).

Voluntary participation: It was explicitly emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary, and participants could withdraw from the study at any point.

Confidentiality and anonymity: Participants were assured that the collected data, including interview recordings and transcripts, would be anonymized. Their identities would not be revealed in any research publications or presentations.

Data security: All recordings and transcripts will be stored using secure protocols to ensure participant privacy.

Minimal risk: The interview process was designed to minimize any potential harm or discomfort to the participants.

Data analysis

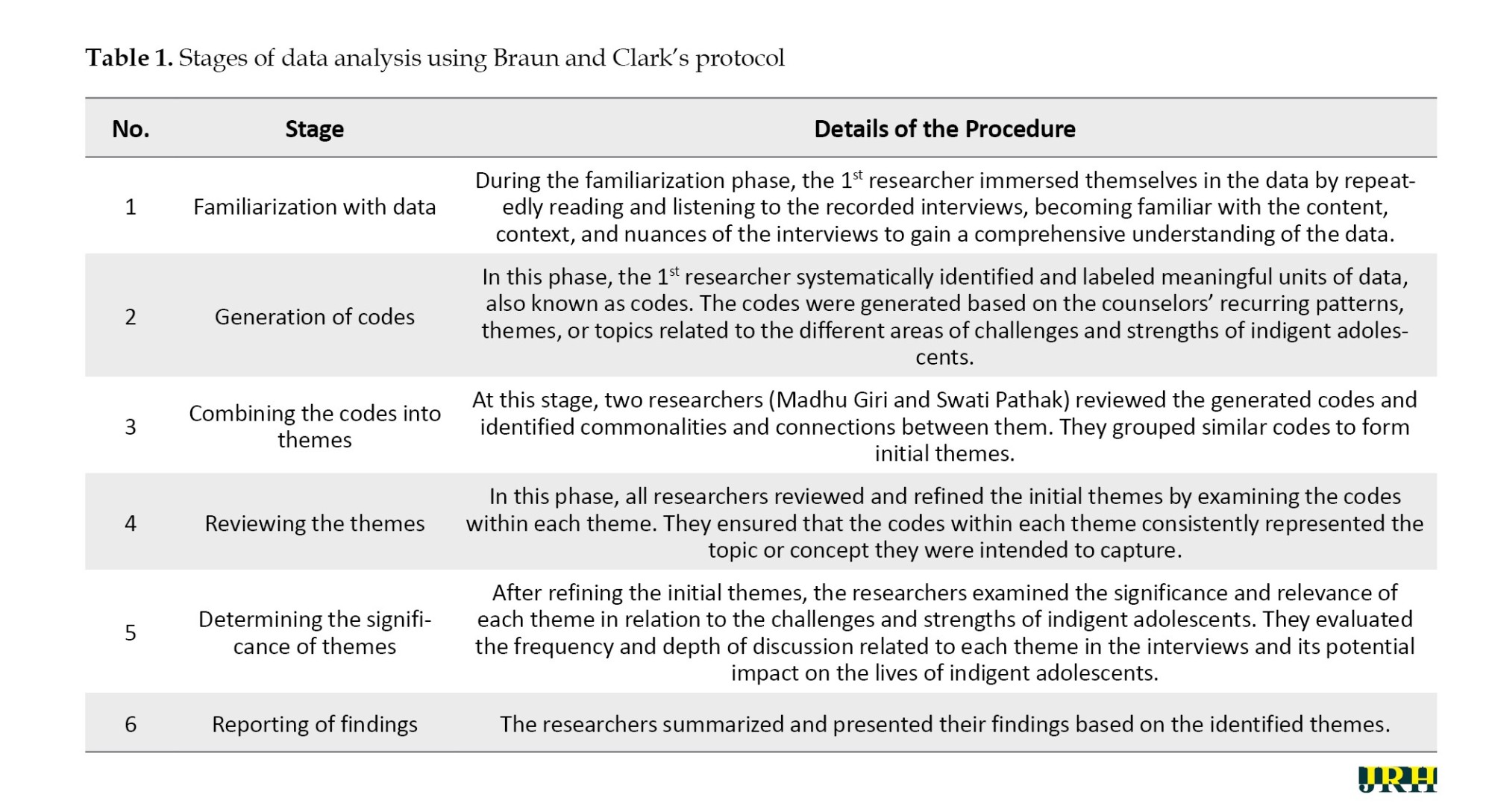

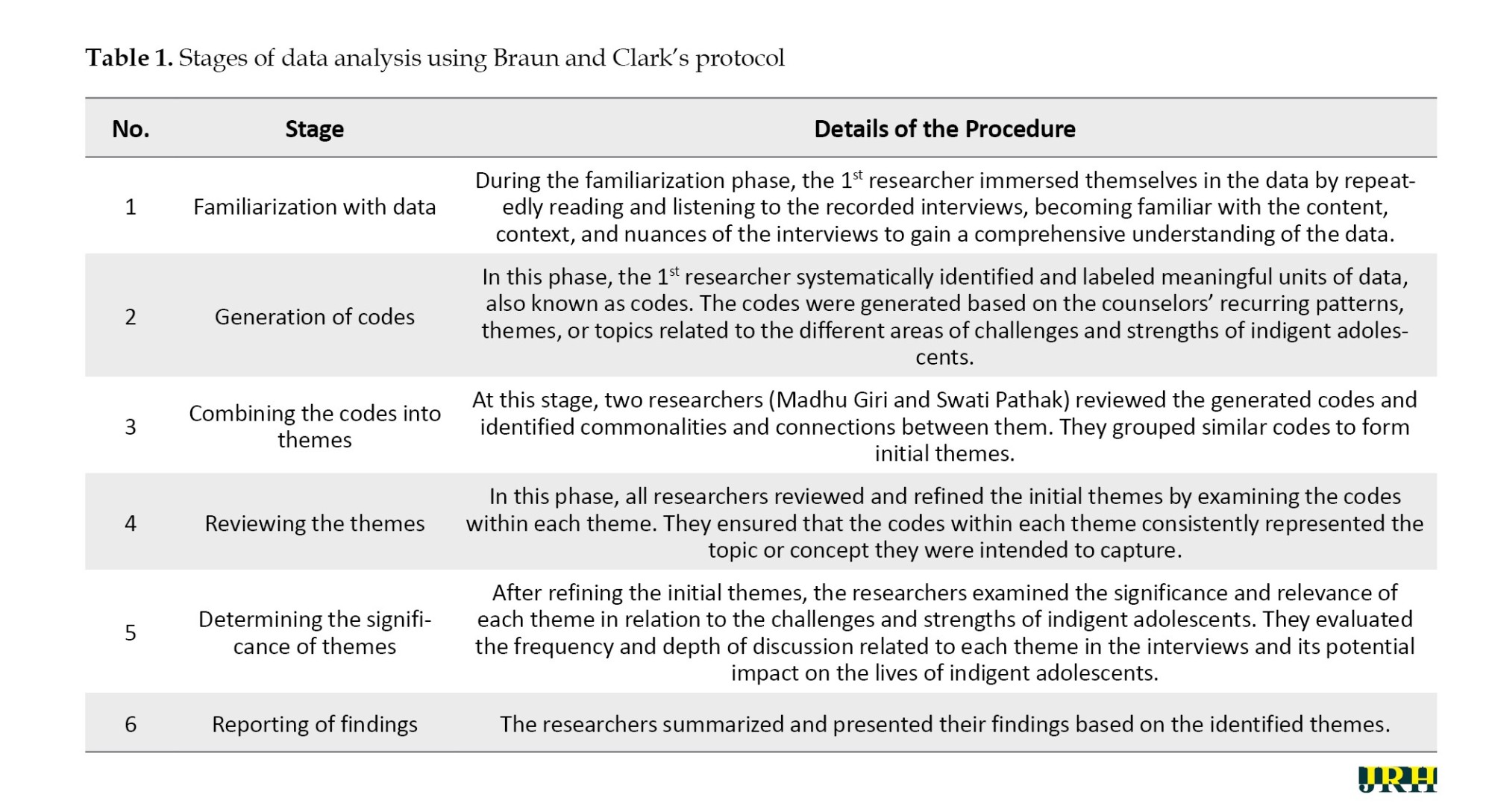

Thematic analysis of the personal interviews was done following Braun and Clark’s protocol [9]; a detailed description of each step is provided in Table 1.

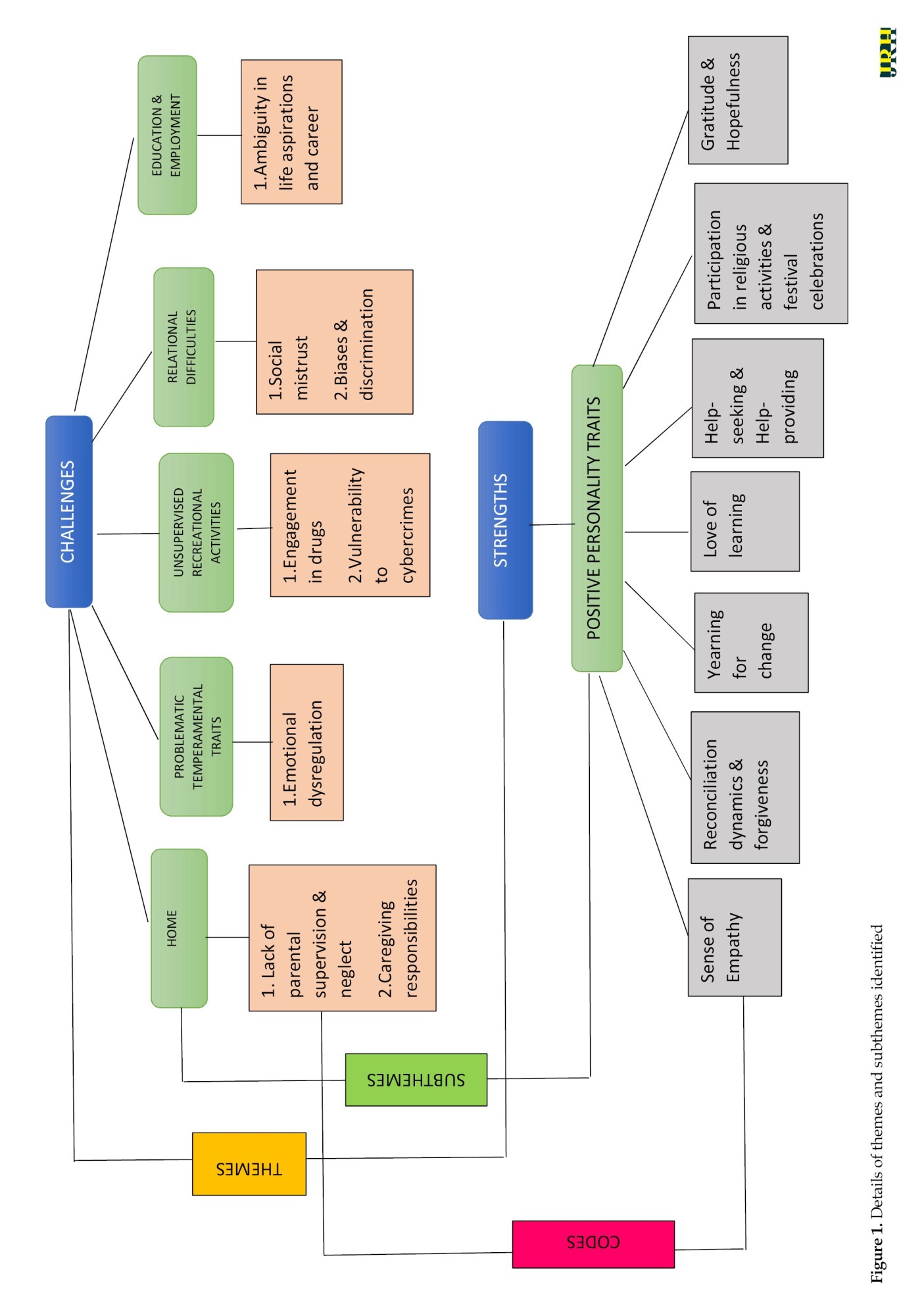

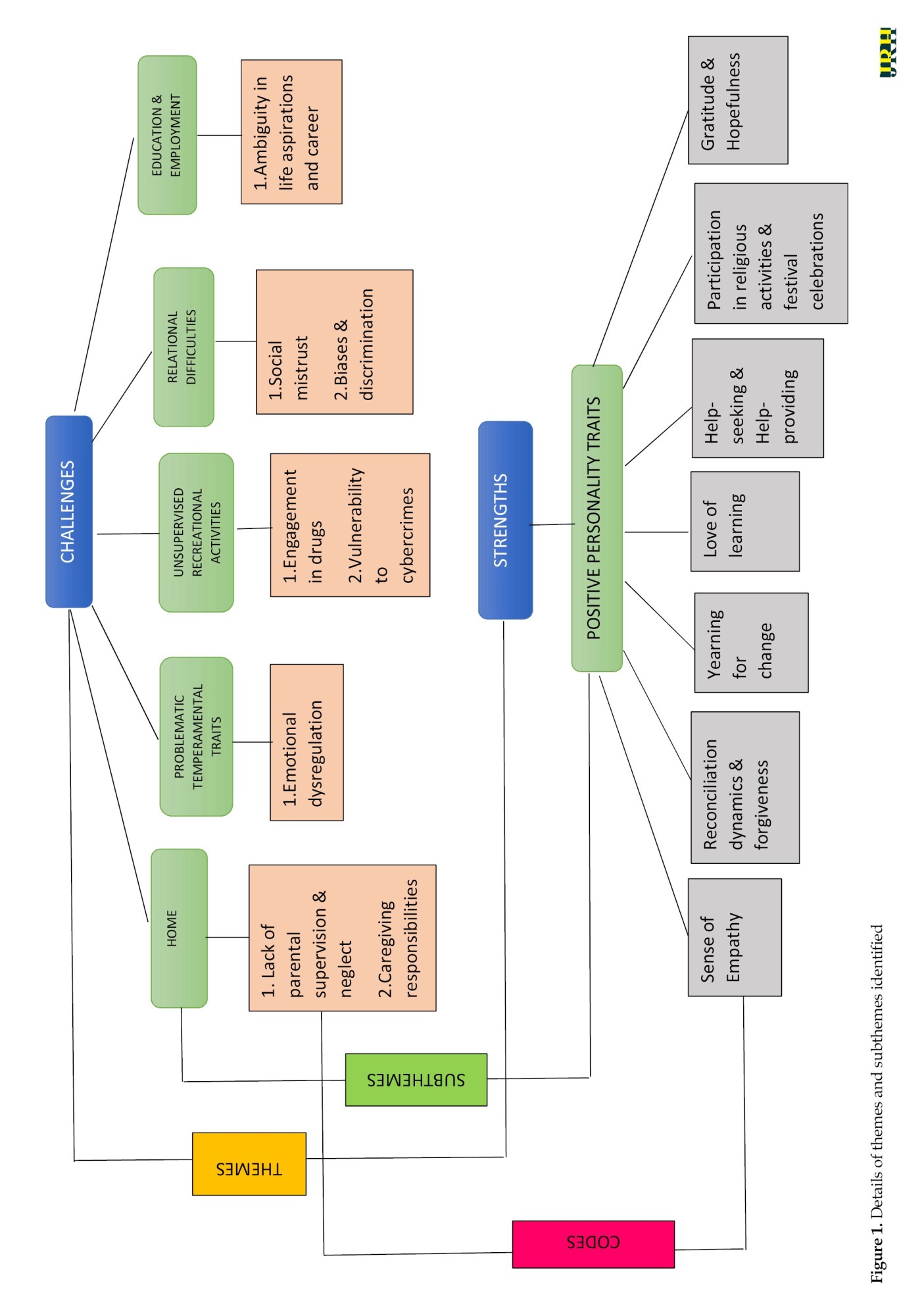

Data analysis occurred concurrently with the interviews (first three stages). After eight interviews, the process was halted when no new information emerged regarding challenges, or when counselors became uncertain about specific strengths. A final review of all themes was then conducted (Figure 1).

Results

Challenges of indigent adolescents

Lack of parental supervision and neglect: Parental supervision is crucial to a child’s development and well-being. It involves the consistent presence and guidance of parents and caregivers in a child’s life, ensuring their safety, emotional support, and appropriate behavior. When this constant supervision from parents or caregivers is absent, it is referred to as neglect. Neglect is a normal phenomenon for children living in families below the poverty line [10,11-13].

“Then the other issue is parental neglect because both the parents are working. The mother is a domestic helper so she goes in the morning, and comes back late in the evening. So they reach home, they don’t even get tiffin boxes, they don’t have anything to eat during lunch simply because there’s nobody to cook at home… They are the only ones and they have to take care of their siblings... so because of this familial neglect, they look for love outside” (Respondent (R) 8).

According to the ecological-transactional model [14], poverty creates stress that prevents parents from meeting their child’s material and emotional needs. This interplay between family dynamics and external circumstances is the root cause of neglect, as parents often struggle to meet their basic needs. Parent-adolescent differences in communication styles (i.e. parental solicitation and behavioral control, as well as adolescent disclosure), along with parental styles such as discipline and control, are associated with poorer well-being [15] and a higher prevalence of internalized and externalized problems [3, 16].

Vulnerability to cybercrime: Almost all participants reported that adolescents living in poverty are highly prone to emotional abuse, with the primary cause being the unavailability of parents at home due to the nature of their work to provide for the family. The emotional unavailability of parents and lack of supervision lead children to seek fulfillment of their love and belongingness needs outside the family.

“They fall prey to romantic relationships, so a lot of sexual crimes or cybercrimes, I’ve seen in such a population, cyber-crimes in the sense that they share certain intimate pictures with their partners, and then the partners blackmail them. And they say that they’ll upload their pictures on various websites if they don’t give them sexual favors” (R1).

Adolescents, who already struggle to manage their emotions effectively, often fall into traps that make them vulnerable to crimes perpetrated against them or lead them to associate with individuals who introduce them to deviant behaviors, which can severely damage their emotional and social well-being. Some find themselves in hopeless situations where they believe there is no way out [17].

Emotional dysregulation: Almost all participants reported a lack of emotional regulation among adolescents from disadvantaged families, which manifests in behaviors, such as verbal outbursts (shouting, screaming, or crying), dissociation, aggressive and violent behavior, and trouble maintaining social relationships, especially with elders.

Aggression: A lot of irritability you’ll find among them. It’s like stress tolerance is not there in some children. Slight inconvenience and they would dissociate and I have seen in a lot of cases where they get dizzy and fall….” (R1).

Paulus [16] defined emotional dysregulation as the inability to regulate the intensity and quality of emotions (such as fear, anger, and sadness), in order to generate an appropriate emotional response, manage excitability, mood instability, and emotional over-reactivity, and return to an emotional baseline. Evans [18] has shown the physiological implications of childhood and adolescent exposure to poverty. At the brain level, childhood poverty affects the functioning of specific regions (such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex) that play an important role in emotional regulation. These brain areas are also sensitive to stress and stress hormones. This body of evidence suggests that the impacts of emotional regulation related to childhood poverty are more pronounced under conditions of increased stress, further indicating the need to identify stressful situations for these children, such as exams, conflicts at home or among peers, or shocks due to significant family debt, and to support them with unconditional positive regard.

Engagement in drug use: Drug use and abuse is the major challenge reported among adolescents living in unsupervised families.

“Because parents are not there to monitor their kids they do all kinds of stuff which are not healthy for them… most of them are into some or the other kind of substance use…. girls hide them but they also are into it... not very hard drugs but yes beedi weed... they all do such kind of stuff…” (R3).

One major concern for counselors is regulating the behavior of adolescents when they return home after school or community-care centers, as they are often unsupervised. This lack of supervision puts these adolescents at risk of drug use and abuse, with the severity of the issue depending on gender. Boys are generally at risk of using hard/illicit drugs while girls are majorly involved in smoking beedis and tobacco; however, some girls are also equally prone to engage in hard drug use. These findings are supported by statistics from a study conducted by Sharma and Chaudhary, which reported that, along with alcohol and cannabis, 46.36% of teenagers living in slums used smokeless and smoked tobacco, and other psychoactive drugs (cannabis), beginning their drug use at a young age [16].

Life aspirations and career ambiguity: Some participants indicated that how individuals perceive their lives significantly influences their aspirations for the future. They reported that children and adolescents often have a short-sighted outlook on life, leading them to live in the present without much consideration for the future, which affects their planning for life. Most adolescents in their secondary high school are also very unclear about their education and career prospects.

“They do have a goal in life… majority of them want to change their situation. They don’t say big things. It’s not a big picture but then they know that I am getting this opportunity to study. I have to do something good in my life and this is where I want to go. Some of them, even if they don’t know where they want to go, know that they have to do something…. they want to do something for their parents, but not knowing what to do or how to do is one of the ambiguities that they face…moreover, they are not very open towards the educational options available” (R2).

Students who set goals for themselves, keep track of their achievements, and take responsibility for achieving those goals feel a sense of empowerment [17]. Lack of supervision, proper and timely guidance, relevant information, motivation, fear of failure, and the absence of an ideal figure in their lives often lead adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds to have a very poor understanding of how to set plans for their futures [18]. Interviews revealed that these children often lose track of their set goals, especially academic plans, as they frequently lose motivation or tend to give up in the face of failures. They often leave it up to external factors to define their future.

Societal mistrust and bias: A major social challenge these adolescents face is gaining the trust of other members of society, especially those associated with upper socio-economic classes. They are often subjected to discrimination and abandonment due to preconceived notions about their character, capabilities, and intentions.

“They often face such difficulties in markets, in social gatherings, etc. people are often suspicious of them…in turn, they also don’t have a very easy-going attitude towards other people” (R2)

This discrimination, abandonment, and rejection by society further impact their self-confidence and manifest in various internalized and externalized forms of psychopathology. Adolescents with high levels of trust have more social support, which protects them against substance abuse. There is evidence that people with low socioeconomic status have lower levels of trust than others [19].

Strengths

Sense of Empathy: It was reported that since students come from nearby localities, they are often aware of each other’s home conditions and the kinds of problems their peers are facing; as a result, these children often exhibit an empathetic attitude toward their friends and classmates.

“They know each other’s family situations since all are living nearby only, what kind of problems the other kid is facing they are well-aware so they are empathetic towards each other. They become upset when any of their friends get hurt, and they accompany them if any kind of help is required. However, it is not the same ::::case when:::: it comes to elder family members or seniors at school, they don’t go well with them” (R1).

It was reported that they do their best to help any of their friends who get into trouble. However, a lack of perspective-taking has also been noted regarding senior members of their community, family, and the opposite gender. Davis [20] showed the mediating role of parenting practices from the perspective of adolescents experiencing economic stress. Life events indirectly and positively forecast acts of kindness through the presence of empathic concern. Additionally, the combination of empathic concern and perspective-taking played a role in predicting empathic responses. The findings highlighted connections that validate the concept of altruism emerging from hardship, indicating that life stressors may not always have a negative impact and could instead foster resilience and social bonds among young adults, given certain circumstances [21].

Reconciliation dynamics and forgiveness: When the question was put forward as to how these kids are in reconciling; counselors reported that they often recon- cile with their peers and friends easily but hold grudges against the elder members of their family and commu- nity if they have done any wrong to them. A kind of ten- sion in relation to elder members is quite often reported and they are often clueless as to how to deal with those feelings.

“They’re more forgiving…. As long as the other person is ready to ask for forgiveness”(R4).

Forgiveness narratives are expected to exhibit a higher frequency of apologetic responses from the offender and more favorable attributions regarding the intentions of the offender, in comparison to non-forgiveness situations [22].

Yearning for change: One question in the interview was how these adolescents perceive their lives, and a follow-up probe asked what kinds of complaints they often have. Counselors responded that the adolescents do not have many complaints about their lives, but they do have a desire to change their current conditions.

“All of them wish for a different life. Because some of them don’t even have the basic necessities of life. And it’s incorrect to believe that they would be and they should be satisfied with their lives. Most of them are not” (R5).

Disadvantaged youth often find purpose by hoping to improve their families’ lives and expressing gratitude for their parents’ sacrifices. They view education as a tool for positive change, inspired by teachers and their own desire to make a difference. Cultivating a sense of purpose in economically disadvantaged young individuals can enhance their lives and contribute positively to their communities [23].

Love of learning: When asked about students who stand out despite living in similar environments yet maintaining a different and optimistic outlook on life, counselors reported that such adolescents tend to pay attention when psychoeducation programs are organized for them. They not only engage with these programs but often participate fully and follow up with their counselors after applying the skills they have learned upon returning home. In class, these students are also quite curious and show interest in the new information that teachers and counselors impart to them.

“When such things are taught to them…they listen to me very carefully. They try to learn and grasp the things they are able to grasp also and they try to implement them… they come back to me and they tell me… if it worked or not....” (R6).

The love of learning is the most consistently associated character strength linked to a lowered risk of drug use and sexual activity during adolescence among both girls and boys [24]. Family plays a significant role in fostering a love of learning and empowering adolescents to display such strengths in different situations [25].

Help-seeking and help-providing behavior: When asked about resilient adolescents, counselors reported that those who often seek help from their peers, teachers, counselors, and other elder members of their family when they are in need or feeling confused are more likely to navigate out of problematic situations than adolescents who do not come out of their shells and keep their problems to themselves.

“Some of the other thing we will do something, plus their help-seeking nature. They’re not reluctant to seek help…I have to do all of this by myself and they are very, very willing to seek help” (R7).

Hence, resilient adolescents tend to reach out to others or seek help when they are in need. Overall, it was reported that these adolescents often engage in help-seeking as well as help-providing behaviors. When any of their classmates or friends get injured, they take them to the health centers at school and support them during a crisis. As previously noted, they are quite aware of each other’s familial situations and act empathetically toward one another. While studying street children at risk of substance abuse, Pandian and Lakshmana [24] found that only 2% of adolescents reported having anyone in their lives to whom they can rely for help when needed.

Attachment to religion and festivals: Resilient, indigent adolescents also feel connected to their religion and culture and often engage in celebrations arranged by their schools and communities with great enthusiasm.

“Students who feel more connected to the family and community have a similarity that they believe in some or the other religion…They celebrate every festival with the same zeal and enthusiasm…. throughout the year. The real fun that they get is from planning and then executing the celebrations among their friends and family” (R5).

They enjoy the get-together opportunities that these festivities bring to them. Some of them take the lead in organizing the events, while some of them are great team builders who inspire others to work in teams and showcase their talents whenever they get any opportu- nity. Howard and colleagues [27] reported a significant and inverse relationship between adversity and existen- tial well-being, with adversity predicting a desire to con- nect with a higher power. They enjoy the opportunities for togetherness that these festivities bring. Some take the lead in organizing the events, while others are great team builders who inspire their peers to work collabora- tively and showcase their talents whenever they have the chance. Also they reported a significant inverse relationship between adversity and existential well-being, with adversity predicting a desire to connect with a higher power.

Gratitude and hopefulness: Counselors reported that resilient, disadvantaged adolescents demonstrate an understanding of their parents’ conditions; they empathize with them and hope to provide a better life for them when they take care of their parents in adulthood.

“I think, whatever stresses they have faced in their lives. They are been able to come out of those places because of such an attitude and such an approach to life so that has motivated them even further that no matter how difficult, the situation may feel there is light at the end of the tunnel. So suppose that is what they have seen their parents live like that and they also imbibed that attitude in them…they feel grateful to their parents for not giving up in those difficult situations… for providing them protection in those challenging times” (R3).

A Guatemalan study found links between envy and lower well-being and strained relationships, while gratitude was associated with happiness and kindness. Encouraging gratitude may be key to helping teens face challenges [28].

Discussion

Positive youth development (PYD) is an approach that focuses on nurturing the strengths and potential of young people to promote their holistic development. For economically disadvantaged youth, PYD has significant implications for a strengths-based approach to their development by acknowledging their resilience, creativity, and potential for growth [28]. PYD interventions build upon existing strengths rather than focusing solely on deficits, empowering youth to advocate for themselves and create positive changes. Overall, the present study sheds light on the varied adversities experienced by economically disadvantaged adolescents in India, including inadequate parental supervision, susceptibility to cyber threats, emotional dysregulation, involvement in substance use, ambiguity in life goals, and challenges in maintaining interpersonal authenticity and trust. These factors underscore the intricate socio-economic landscape they navigate. Previous research is consistent with the present findings, indicating that inter-parent discord is significantly associated with all forms of conduct disorders among children experiencing persistent poverty [27]. Moreover, unmarried migrant adolescent girls face challenges in accessing education, employment, social opportunities, and services owing to restrictions on freedom of movement, weak social networks, and limited awareness of available opportunities and services [28]. Furthermore, it was also found that stressful life events appear to disrupt the adaptive processing of emotions [29].

However, within this context, the exhibited strengths, such as peer-oriented perspective-taking, tendencies toward forgiveness, aspirations for improved circumstances, enthusiasm for learning, pro-social behavior, and connections to religious and festival practices, offer promising avenues for context-specific interventions. It was also noticed that having a warm and supportive mother, perceiving community support, and exhibiting higher levels of enculturation were associated with an increased likelihood of pro-social outcomes among youth living in moderate- to high-adversity households [30]. Recognizing and harnessing these strengths can inform culturally sensitive approaches to support and empower economically disadvantaged Indian adolescents, promoting resilience and adaptive coping mechanisms amidst their unique challenges. Further empirical research and community-driven initiatives are imperative for developing evidence-based strategies that address the distinctive needs of this vulnerable demographic and pave the way for a more promising future within the Indian socio-cultural milieu [31].

Conclusion

This study explored the complex lives of disadvantaged adolescents in India, uncovering both their struggles and strengths. Their experiences are shaped by poverty and their inner resources. Understanding these factors is key to creating effective interventions and support systems. By addressing their challenges and building on their strengths, we can empower them to thrive.

Limitations

This study has only taken account of counselors’ perspectives when exploring the strengths and challenges faced by indigent adolescents. Although considering the training and role of counselors is important, as they play a significant role in understanding the challenges and strengths of these adolescents, incorporating the perspectives of parents and social workers could enhance a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and strengths faced by disadvantaged adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of CHRIST University (Code: CU: RCEC/00480/08/23).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to the study participants for their time and invaluable insights. Their willingness to share their experiences was instrumental to this research.

References

Adolescence is a critical period of development during which individuals undergo physical changes, navigate social and emotional complexities, make educational decisions, and develop their identities. Unaddressed challenges during this time can lead to mental health issues and social exclusion [1, 2].

The Bronfenbrenner bioecological model highlights how poverty can become a breeding ground for mental health struggles and personality challenges in adolescents. At the close-up level (microsystem), poverty creates an unstable environment characterized by crowded housing, limited access to healthy food, and exposure to parental stress. This can trigger anxiety, insecurity, and concentration problems in teenagers. Moving outward (mesosystem), poverty strains relationships with family, school, and community [3]. The lack of after-school programs, negative peer influences in under-resourced neighborhoods, and strained family dynamics due to financial pressure can all lead to feelings of isolation, lack of support, and lower self-esteem [4]. Beyond the immediate surroundings (exosystem), poverty limits access to resources, like quality healthcare, mental health services, and educational opportunities. This lack of external support can exacerbate existing mental health issues and hinder the development of healthy coping mechanisms. Finally, the broader context (macrosystem) plays a role as well. Societal factors, like poverty itself and policies that perpetuate it, create a sense of hopelessness and powerlessness in adolescents. Discrimination, a lack of affordable housing, and limited job opportunities for parents all contribute to a negative mental state and overall well-being [5]. In conclusion, poverty acts like a constant stressor across all these layers of the Bronfenbrenner model, shaping adolescents’ personalities through limited opportunities and fostering negative experiences that ultimately impact their mental health.

A significant amount of research enables us to understand the various challenges that indigent adolescents (suffering from extreme poverty, synonymous with impoverished) face [6, 7]. There is a substantial gap in addressing the mental health needs of adolescents, particularly those experiencing economic hardships [8]. However, it is noteworthy that despite all the challenges and adversities, this population demonstrates resilience, flexibility, hope, and positive growth. Although there is a scarcity of research focusing on interventions that promote the well-being of indigent adolescents, the World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the importance of enhancing positive traits in adolescents, such ::::as char::::acter strengths, to promote their well-being [8]. Character strengths are positive traits that can be exercised in daily life activities to achieve an authentic sense of well-being, happiness, and flourishing [9]. In-depth studies are needed to explore the unique strengths of disadvantaged youth beyond existing models. This would involve qualitative research with various stakeholders to understand how these teens overcome the challenges of poverty and thrive.

School counselors offer a unique view of disadvantaged teens. They observe firsthand the impact of poverty on anxieties, coping skills, and even mental health. Unlike statistics, counselors go beyond the numbers to understand the teens’ resilience and potential. They bridge the gap between the teens’ experiences and the underlying issues, highlighting both challenges and strengths.

Methods

Aim and objectives

This study aimed to evaluate counselors’ insights into the psycho-social challenges and strengths of disadvantaged adolescents.

Design

Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with counselors using a semi-structured interview guide. The guide, based on the study goals and literature review, covered key areas, like home life, education, and mental health. Open-ended questions and probes were used to explore the challenges and strengths of disadvantaged adolescents. The guide was validated by two experts with extensive experience in counseling and social work with this population.

Procedure

Sample

This study focused on counselors as a key source of information regarding the risk factors and protective strengths of disadvantaged teens. Counselors’ close relationships with these teens allow for unbiased insights into their challenges and resources. This offers a more complete picture than other stakeholders, like teachers, who might have expectations that cloud their judgment. Counselors act as a bridge between the teens’ experiences and a deeper understanding of their needs. They can offer a nuanced viewpoint that acknowledges the obstacles posed by poverty while emphasizing the teenagers’ inner resources and growth potential.

Data collection

Counselors working with at-risk adolescents (in schools and various community day-care centers in the Delhi/NCR region) were approached through a snowball sampling technique. Since traditional sampling methods might overlook counselors embedded within the support network for indigent adolescents, snowball sampling provided a strategic solution. It capitalized on counselors’ connections with other counselors working in social service agencies, schools, and community centers specifically serving underprivileged youth. By relying on counselor referrals, researchers were able to access a pool of participants with demonstrably relevant experience, thereby maintaining credibility and trust.

Inclusion criteria:

1) At least three years of experience in counseling indigent adolescents. This ensures exposure to various issues and allows counselors to develop effective strategies that leverage adolescents’ inherent strengths

2) Proficiency in speaking English

3) Willingness to dedicate at least one hour for the interview

Exclusion criteria

Counselors from residential schools. Their uniform environment would not reveal the impact of poverty and individual strengths in overcoming challenges.

Ethical considerations:

A detailed briefing: Participants were thoroughly briefed about the study’s aims, objectives, and the expected interview duration (approximately 1 hour).

Voluntary participation: It was explicitly emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary, and participants could withdraw from the study at any point.

Confidentiality and anonymity: Participants were assured that the collected data, including interview recordings and transcripts, would be anonymized. Their identities would not be revealed in any research publications or presentations.

Data security: All recordings and transcripts will be stored using secure protocols to ensure participant privacy.

Minimal risk: The interview process was designed to minimize any potential harm or discomfort to the participants.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis of the personal interviews was done following Braun and Clark’s protocol [9]; a detailed description of each step is provided in Table 1.

Data analysis occurred concurrently with the interviews (first three stages). After eight interviews, the process was halted when no new information emerged regarding challenges, or when counselors became uncertain about specific strengths. A final review of all themes was then conducted (Figure 1).

Results

Challenges of indigent adolescents

Lack of parental supervision and neglect: Parental supervision is crucial to a child’s development and well-being. It involves the consistent presence and guidance of parents and caregivers in a child’s life, ensuring their safety, emotional support, and appropriate behavior. When this constant supervision from parents or caregivers is absent, it is referred to as neglect. Neglect is a normal phenomenon for children living in families below the poverty line [10,11-13].

“Then the other issue is parental neglect because both the parents are working. The mother is a domestic helper so she goes in the morning, and comes back late in the evening. So they reach home, they don’t even get tiffin boxes, they don’t have anything to eat during lunch simply because there’s nobody to cook at home… They are the only ones and they have to take care of their siblings... so because of this familial neglect, they look for love outside” (Respondent (R) 8).

According to the ecological-transactional model [14], poverty creates stress that prevents parents from meeting their child’s material and emotional needs. This interplay between family dynamics and external circumstances is the root cause of neglect, as parents often struggle to meet their basic needs. Parent-adolescent differences in communication styles (i.e. parental solicitation and behavioral control, as well as adolescent disclosure), along with parental styles such as discipline and control, are associated with poorer well-being [15] and a higher prevalence of internalized and externalized problems [3, 16].

Vulnerability to cybercrime: Almost all participants reported that adolescents living in poverty are highly prone to emotional abuse, with the primary cause being the unavailability of parents at home due to the nature of their work to provide for the family. The emotional unavailability of parents and lack of supervision lead children to seek fulfillment of their love and belongingness needs outside the family.

“They fall prey to romantic relationships, so a lot of sexual crimes or cybercrimes, I’ve seen in such a population, cyber-crimes in the sense that they share certain intimate pictures with their partners, and then the partners blackmail them. And they say that they’ll upload their pictures on various websites if they don’t give them sexual favors” (R1).

Adolescents, who already struggle to manage their emotions effectively, often fall into traps that make them vulnerable to crimes perpetrated against them or lead them to associate with individuals who introduce them to deviant behaviors, which can severely damage their emotional and social well-being. Some find themselves in hopeless situations where they believe there is no way out [17].

Emotional dysregulation: Almost all participants reported a lack of emotional regulation among adolescents from disadvantaged families, which manifests in behaviors, such as verbal outbursts (shouting, screaming, or crying), dissociation, aggressive and violent behavior, and trouble maintaining social relationships, especially with elders.

Aggression: A lot of irritability you’ll find among them. It’s like stress tolerance is not there in some children. Slight inconvenience and they would dissociate and I have seen in a lot of cases where they get dizzy and fall….” (R1).

Paulus [16] defined emotional dysregulation as the inability to regulate the intensity and quality of emotions (such as fear, anger, and sadness), in order to generate an appropriate emotional response, manage excitability, mood instability, and emotional over-reactivity, and return to an emotional baseline. Evans [18] has shown the physiological implications of childhood and adolescent exposure to poverty. At the brain level, childhood poverty affects the functioning of specific regions (such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex) that play an important role in emotional regulation. These brain areas are also sensitive to stress and stress hormones. This body of evidence suggests that the impacts of emotional regulation related to childhood poverty are more pronounced under conditions of increased stress, further indicating the need to identify stressful situations for these children, such as exams, conflicts at home or among peers, or shocks due to significant family debt, and to support them with unconditional positive regard.

Engagement in drug use: Drug use and abuse is the major challenge reported among adolescents living in unsupervised families.

“Because parents are not there to monitor their kids they do all kinds of stuff which are not healthy for them… most of them are into some or the other kind of substance use…. girls hide them but they also are into it... not very hard drugs but yes beedi weed... they all do such kind of stuff…” (R3).

One major concern for counselors is regulating the behavior of adolescents when they return home after school or community-care centers, as they are often unsupervised. This lack of supervision puts these adolescents at risk of drug use and abuse, with the severity of the issue depending on gender. Boys are generally at risk of using hard/illicit drugs while girls are majorly involved in smoking beedis and tobacco; however, some girls are also equally prone to engage in hard drug use. These findings are supported by statistics from a study conducted by Sharma and Chaudhary, which reported that, along with alcohol and cannabis, 46.36% of teenagers living in slums used smokeless and smoked tobacco, and other psychoactive drugs (cannabis), beginning their drug use at a young age [16].

Life aspirations and career ambiguity: Some participants indicated that how individuals perceive their lives significantly influences their aspirations for the future. They reported that children and adolescents often have a short-sighted outlook on life, leading them to live in the present without much consideration for the future, which affects their planning for life. Most adolescents in their secondary high school are also very unclear about their education and career prospects.

“They do have a goal in life… majority of them want to change their situation. They don’t say big things. It’s not a big picture but then they know that I am getting this opportunity to study. I have to do something good in my life and this is where I want to go. Some of them, even if they don’t know where they want to go, know that they have to do something…. they want to do something for their parents, but not knowing what to do or how to do is one of the ambiguities that they face…moreover, they are not very open towards the educational options available” (R2).

Students who set goals for themselves, keep track of their achievements, and take responsibility for achieving those goals feel a sense of empowerment [17]. Lack of supervision, proper and timely guidance, relevant information, motivation, fear of failure, and the absence of an ideal figure in their lives often lead adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds to have a very poor understanding of how to set plans for their futures [18]. Interviews revealed that these children often lose track of their set goals, especially academic plans, as they frequently lose motivation or tend to give up in the face of failures. They often leave it up to external factors to define their future.

Societal mistrust and bias: A major social challenge these adolescents face is gaining the trust of other members of society, especially those associated with upper socio-economic classes. They are often subjected to discrimination and abandonment due to preconceived notions about their character, capabilities, and intentions.

“They often face such difficulties in markets, in social gatherings, etc. people are often suspicious of them…in turn, they also don’t have a very easy-going attitude towards other people” (R2)

This discrimination, abandonment, and rejection by society further impact their self-confidence and manifest in various internalized and externalized forms of psychopathology. Adolescents with high levels of trust have more social support, which protects them against substance abuse. There is evidence that people with low socioeconomic status have lower levels of trust than others [19].

Strengths

Sense of Empathy: It was reported that since students come from nearby localities, they are often aware of each other’s home conditions and the kinds of problems their peers are facing; as a result, these children often exhibit an empathetic attitude toward their friends and classmates.

“They know each other’s family situations since all are living nearby only, what kind of problems the other kid is facing they are well-aware so they are empathetic towards each other. They become upset when any of their friends get hurt, and they accompany them if any kind of help is required. However, it is not the same ::::case when:::: it comes to elder family members or seniors at school, they don’t go well with them” (R1).

It was reported that they do their best to help any of their friends who get into trouble. However, a lack of perspective-taking has also been noted regarding senior members of their community, family, and the opposite gender. Davis [20] showed the mediating role of parenting practices from the perspective of adolescents experiencing economic stress. Life events indirectly and positively forecast acts of kindness through the presence of empathic concern. Additionally, the combination of empathic concern and perspective-taking played a role in predicting empathic responses. The findings highlighted connections that validate the concept of altruism emerging from hardship, indicating that life stressors may not always have a negative impact and could instead foster resilience and social bonds among young adults, given certain circumstances [21].

Reconciliation dynamics and forgiveness: When the question was put forward as to how these kids are in reconciling; counselors reported that they often recon- cile with their peers and friends easily but hold grudges against the elder members of their family and commu- nity if they have done any wrong to them. A kind of ten- sion in relation to elder members is quite often reported and they are often clueless as to how to deal with those feelings.

“They’re more forgiving…. As long as the other person is ready to ask for forgiveness”(R4).

Forgiveness narratives are expected to exhibit a higher frequency of apologetic responses from the offender and more favorable attributions regarding the intentions of the offender, in comparison to non-forgiveness situations [22].

Yearning for change: One question in the interview was how these adolescents perceive their lives, and a follow-up probe asked what kinds of complaints they often have. Counselors responded that the adolescents do not have many complaints about their lives, but they do have a desire to change their current conditions.

“All of them wish for a different life. Because some of them don’t even have the basic necessities of life. And it’s incorrect to believe that they would be and they should be satisfied with their lives. Most of them are not” (R5).

Disadvantaged youth often find purpose by hoping to improve their families’ lives and expressing gratitude for their parents’ sacrifices. They view education as a tool for positive change, inspired by teachers and their own desire to make a difference. Cultivating a sense of purpose in economically disadvantaged young individuals can enhance their lives and contribute positively to their communities [23].

Love of learning: When asked about students who stand out despite living in similar environments yet maintaining a different and optimistic outlook on life, counselors reported that such adolescents tend to pay attention when psychoeducation programs are organized for them. They not only engage with these programs but often participate fully and follow up with their counselors after applying the skills they have learned upon returning home. In class, these students are also quite curious and show interest in the new information that teachers and counselors impart to them.

“When such things are taught to them…they listen to me very carefully. They try to learn and grasp the things they are able to grasp also and they try to implement them… they come back to me and they tell me… if it worked or not....” (R6).

The love of learning is the most consistently associated character strength linked to a lowered risk of drug use and sexual activity during adolescence among both girls and boys [24]. Family plays a significant role in fostering a love of learning and empowering adolescents to display such strengths in different situations [25].

Help-seeking and help-providing behavior: When asked about resilient adolescents, counselors reported that those who often seek help from their peers, teachers, counselors, and other elder members of their family when they are in need or feeling confused are more likely to navigate out of problematic situations than adolescents who do not come out of their shells and keep their problems to themselves.

“Some of the other thing we will do something, plus their help-seeking nature. They’re not reluctant to seek help…I have to do all of this by myself and they are very, very willing to seek help” (R7).

Hence, resilient adolescents tend to reach out to others or seek help when they are in need. Overall, it was reported that these adolescents often engage in help-seeking as well as help-providing behaviors. When any of their classmates or friends get injured, they take them to the health centers at school and support them during a crisis. As previously noted, they are quite aware of each other’s familial situations and act empathetically toward one another. While studying street children at risk of substance abuse, Pandian and Lakshmana [24] found that only 2% of adolescents reported having anyone in their lives to whom they can rely for help when needed.

Attachment to religion and festivals: Resilient, indigent adolescents also feel connected to their religion and culture and often engage in celebrations arranged by their schools and communities with great enthusiasm.

“Students who feel more connected to the family and community have a similarity that they believe in some or the other religion…They celebrate every festival with the same zeal and enthusiasm…. throughout the year. The real fun that they get is from planning and then executing the celebrations among their friends and family” (R5).

They enjoy the get-together opportunities that these festivities bring to them. Some of them take the lead in organizing the events, while some of them are great team builders who inspire others to work in teams and showcase their talents whenever they get any opportu- nity. Howard and colleagues [27] reported a significant and inverse relationship between adversity and existen- tial well-being, with adversity predicting a desire to con- nect with a higher power. They enjoy the opportunities for togetherness that these festivities bring. Some take the lead in organizing the events, while others are great team builders who inspire their peers to work collabora- tively and showcase their talents whenever they have the chance. Also they reported a significant inverse relationship between adversity and existential well-being, with adversity predicting a desire to connect with a higher power.

Gratitude and hopefulness: Counselors reported that resilient, disadvantaged adolescents demonstrate an understanding of their parents’ conditions; they empathize with them and hope to provide a better life for them when they take care of their parents in adulthood.

“I think, whatever stresses they have faced in their lives. They are been able to come out of those places because of such an attitude and such an approach to life so that has motivated them even further that no matter how difficult, the situation may feel there is light at the end of the tunnel. So suppose that is what they have seen their parents live like that and they also imbibed that attitude in them…they feel grateful to their parents for not giving up in those difficult situations… for providing them protection in those challenging times” (R3).

A Guatemalan study found links between envy and lower well-being and strained relationships, while gratitude was associated with happiness and kindness. Encouraging gratitude may be key to helping teens face challenges [28].

Discussion

Positive youth development (PYD) is an approach that focuses on nurturing the strengths and potential of young people to promote their holistic development. For economically disadvantaged youth, PYD has significant implications for a strengths-based approach to their development by acknowledging their resilience, creativity, and potential for growth [28]. PYD interventions build upon existing strengths rather than focusing solely on deficits, empowering youth to advocate for themselves and create positive changes. Overall, the present study sheds light on the varied adversities experienced by economically disadvantaged adolescents in India, including inadequate parental supervision, susceptibility to cyber threats, emotional dysregulation, involvement in substance use, ambiguity in life goals, and challenges in maintaining interpersonal authenticity and trust. These factors underscore the intricate socio-economic landscape they navigate. Previous research is consistent with the present findings, indicating that inter-parent discord is significantly associated with all forms of conduct disorders among children experiencing persistent poverty [27]. Moreover, unmarried migrant adolescent girls face challenges in accessing education, employment, social opportunities, and services owing to restrictions on freedom of movement, weak social networks, and limited awareness of available opportunities and services [28]. Furthermore, it was also found that stressful life events appear to disrupt the adaptive processing of emotions [29].

However, within this context, the exhibited strengths, such as peer-oriented perspective-taking, tendencies toward forgiveness, aspirations for improved circumstances, enthusiasm for learning, pro-social behavior, and connections to religious and festival practices, offer promising avenues for context-specific interventions. It was also noticed that having a warm and supportive mother, perceiving community support, and exhibiting higher levels of enculturation were associated with an increased likelihood of pro-social outcomes among youth living in moderate- to high-adversity households [30]. Recognizing and harnessing these strengths can inform culturally sensitive approaches to support and empower economically disadvantaged Indian adolescents, promoting resilience and adaptive coping mechanisms amidst their unique challenges. Further empirical research and community-driven initiatives are imperative for developing evidence-based strategies that address the distinctive needs of this vulnerable demographic and pave the way for a more promising future within the Indian socio-cultural milieu [31].

Conclusion

This study explored the complex lives of disadvantaged adolescents in India, uncovering both their struggles and strengths. Their experiences are shaped by poverty and their inner resources. Understanding these factors is key to creating effective interventions and support systems. By addressing their challenges and building on their strengths, we can empower them to thrive.

Limitations

This study has only taken account of counselors’ perspectives when exploring the strengths and challenges faced by indigent adolescents. Although considering the training and role of counselors is important, as they play a significant role in understanding the challenges and strengths of these adolescents, incorporating the perspectives of parents and social workers could enhance a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and strengths faced by disadvantaged adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of CHRIST University (Code: CU: RCEC/00480/08/23).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to the study participants for their time and invaluable insights. Their willingness to share their experiences was instrumental to this research.

References

- Nooripour R, Sikström S, Amirinia M, Chenarani H, Emadi F, J Lavie C, et al. Effectiveness of Group Training Based on Choice Theory on Internalizing Problems, Empathy, and Identity Transformations Among Male Adolescents. Journal of Research & Health. 2023; 13(3):197-208. [DOI:10.32598/jrh.13.3.2096.2]

- Bailen NH, Green LM, Thompson RJ. Understanding Emotion in Adolescents: A review of emotional frequency, intensity, instability, and clarity. Emotion Review. 2019; 11(1):63-73. [DOI:10.1177/1754073918768878]

- Zaatari WE, Maalouf I. How the bronfenbrenner bio-ecological system theory explains the development of students’ sense of belonging to school? Sage Open. 2022; 12(4):215824402211340. [DOI:10.1177/21582440221134089]

- Mistry RS, Elenbaas L. It's all in the family: Parents' economic worries and youth's perceptions of financial stress and educational outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2021; 50(4):724-38. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-021-01393-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dhandapani VR, Chandrasekaran S, Singh S, Sood M, Chadda RK, Shah J, et al. Community stakeholders' perspectives on youth mental health in India: Problems, challenges and recommendations. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2021; 15(3):716-22.[DOI:10.1111/eip.12984] [PMID]

- Johnson SE, Lawrence D, Perales F, Baxter J, Zubrick SR. Poverty, parental mental health and child/adolescent mental disorders: Findings from a national Australian survey. Child Indicators Research. 2018; 12(3):963-88. [DOI:10.1007/s12187-018-9564-1]

- Deb S, Ray M. Child abuse and neglect in India, risk factors, and protective measures. In: Deb S, editor. Child safety, welfare and well-being. Berlin: Springer; 2015. [DOI:10.1007/978-81-322-2425-9_4]

- Mehra D, Lakiang T, Kathuria N, Kumar M, Mehra S, Sharma S. Mental health interventions among adolescents in India: A scoping review. Healthcare. 2022; 10(2):337. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10020337] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019; 11(4):589-97. [DOI:10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806]

- Herruzo C, Raya Trenas A, Pino MJ, Herruzo J. Study of the differential consequences of neglect and poverty on adaptive and maladaptive behavior in children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):739. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17030739] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Valtolina GG, Polizzi C, Perricone G. Improving the early assessment of child neglect signs-a new technique for professionals. Pediatric Reports. 2023; 15(2):390-5. [DOI:10.3390/pediatric15020035] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Niu X, Li JY, King DL, Rost DH, Wang HZ, Wang JL. The relationship between parenting styles and adolescent problematic Internet use: A three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2023; 12(3):652–69. [DOI:10.1556/2006.2023.00043] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Paulus FW, Ohmann S, Möhler E, Plener P, Popow C. Emotional dysregulation in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021; 12:628252. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628252] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hinnant JB, Forman-Alberti AB. Deviant peer behavior and adolescent delinquency: Protective effects of inhibitory control, planning, or decision making? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2019; 29(3):682-95. [DOI:10.1111/jora.12405] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Evans GW, De France K. Childhood poverty and psychological well-being: The mediating role of cumulative risk exposure. Development and Psychopathology. 2022; 34(3):911-21. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579420001947] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sharma M, Chaudhary M. A study of drugs and substance abuse among adolescents of slum dwellers. International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2016; 3(4):21-7. [DOI:10.25215/0304.041]

- Bedi JK. Goal setting optimal motivation and academic performance of adolescents in relation to parental involvement [doctoral thesis]. Chandigarh: Panjab University; 2020. [Link]

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018; 6(11):e1196-252. [DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3] [PMID]

- Peviani KM, Brieant A, Holmes CJ, King-Casas B, Kim-Spoon J. Religious social support protects against social risks for adolescent substance use. Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence. 2020; 30(2):361-71. [DOI:10.1111/jora.12529] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Davis AN, Carlo G. The roles of parenting practices, sociocognitive/emotive traits, and prosocial behaviors in low-income adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2018; 62:140-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.011] [PMID]

- Davis AN, Martin-Cuellar A, Luce H. Life events and prosocial behaviors among young adults: Considering the roles of perspective taking and empathic concern. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2019; 180(4-5):205-16. [DOI:10.1080/00221325.2019.1632785] [PMID]

- Wainryb C, Recchia H, Faulconbridge O, Pasupathi M. To err is human: Forgiveness across childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2019; 29(2):509-25. [DOI:10.1111/sode.12413]

- Arslan G. Psychological well-being and mental health in youth: technical adequacy of the comprehensive inventory of thriving. Children. 2023; 10(7):1269. [DOI:10.3390/children10071269] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Howard AH, Roberts M, Mitchell T, Wilke NG. The relationship between spirituality and resilience and well-being: A study of 529 care leavers from 11 nations. Adversity and Resilience Science. 2023; 4(2):177-90. [DOI:10.1007/s42844-023-00088-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Poelker KE, Gibbons JL, Maxwell CA, Elizondo-Quintanilla IL. Envy, gratitude, and well-being among guatemalan adolescents with scarce economic resources. International Perspectives in Psychology. 2017; 6(4):209-26. [DOI:10.1037/ipp0000076]

- Shek DT, Dou D, Zhu X, Chai W. Positive youth development: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2019; 10:131-41. [DOI:10.2147/AHMT.S179946] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Jayaprakash R, Sharija S, Prabhakaran A, Rajamohanan K. Determinants of poor outcome of conduct disorder among children and adolescents: A 1-year follow-up study. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2022; 38(1):38-44. [DOI:10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_82_20]

- Iqbal A, Hassan S, Mahmood H, Tanveer M. Gender equality, education, economic growth and religious tensions nexus in developing countries: A spatial analysis approach. Heliyon. 2022; 8(11):e11394. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11394] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Jacob A, Ravindranath S. Social and emotional well-being of adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds. In: Gupta SK, editor. Handbook of research on child and adolescent psychology practices and interventions. Hershey: IGI Global; 2024. [DOI:10.4018/978-1-6684-9983-2.ch008]

- Pastorelli C, Zuffianò A, Lansford JE, Thartori E, Bornstein MH, Chang L, et al. Positive youth development: Parental warmth, values, and prosocial behavior in 11 cultural groups. Journal of Youth Development. 2021; 16(2-3):379-401. [DOI:10.5195/jyd.2021.1026] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Jongen CS, McCalman J, Bainbridge RG. A systematic scoping review of the resilience intervention literature for indigenous adolescents in CANZUS nations. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020; 7:351. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00351] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2024/01/16 | Accepted: 2024/05/14 | Published: 2024/09/1

Received: 2024/01/16 | Accepted: 2024/05/14 | Published: 2024/09/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |