Volume 15, Issue 3 (May & June 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(3): 283-292 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Armanmehr V, Asgharpourmasouleh A. Social Resilience and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of a Suburban Residential Area in Light of Complexity Theory. J Research Health 2025; 15 (3) :283-292

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2534-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2534-en.html

1- Social Development & Health Promotion Research Center, Gonabad University of Medical Science, Gonabad, Iran.

2- Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran. ,ahmadreza.asgharpour@gmail.com

2- Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 573 kb]

(255 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1519 Views)

Full-Text: (436 Views)

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, officially declared a crisis by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1] on March 11, 2020, brought about multidimensional changes to people’s lives, and the policymakers did not have enough time to respond and adapt to the situation [2]. This pandemic had a complex and multifaceted nature marked by biological, human, and social sub-systems (e.g. public opinion, network media, and government credibility) [3, 4]. People in different countries implemented different measures to respond to this crisis, reflecting their different levels of resilience [5]. Resilience is one of the goals of the United Nations (UN)’ 2030 agenda, which encompasses the core concept of adaptation—a concept that refers to the limits of environmental, socio-political, and cultural compatibility [6]. Social resilience is defined as the ability of social entities and social mechanisms to effectively anticipate, mitigate, and cope with disasters, as well as to engage in recovery activities that minimize social disruptions and reduce the impact of future disasters [7].

Various factors can lead to resilience and cause society members to be more or less affected by a crisis [8]. Information and awareness, sense of identity, financial capital, lifestyle, social partnerships, and economic and social incentives can increase the level of resilience [9]. As experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, joint collective activities and cultural agreement on common values were among the most important aspects of resilience. The provision of public services and adequate access to services [10] was also an important issue [10, 11]. Vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, children, and deprived and marginalized classes demonstrated less social resilience due to limited access to resources and facilities. In addition, people with informal work and daily wages constituted a major at-risk group [12]. Evidence indicates that some geographic regions exhibit greater resilience while others show less during critical conditions [13]. This issue was also visible in the COVID-19 pandemic, as some regions faced more challenges [14].

Since the COVID-19 pandemic was raised as a complex issue [15], the social complexity approach is appropriate to explore the concept of resilience during the pandemic. The meanings and functions of resilience lie in larger social, economic, and political contexts [16]. Only by acknowledging the holistic and complex aspects of the pandemic and avoiding simplistic linear solutions can this experience be adequately and insightfully understood [17]. Unlike biophysical systems, the resilience of a social system depends on the fact that predicting something about the future and sharing it with all actors/agents in the same system can motivate them to participate more. It indicates the role of awareness of agency within these systems. A considerable point is that agency can influence everything, making it related to power. However, actors/agents do not operate in a vacuum; some possess more power to effect change while others have less. Social resilience results from the interactions among individual, collective, and institutional actors [18].

The complexity theory is based on a systemic perspective. Reality is complex and nested, which means its scientific processes cannot be explained by a single cause. In the theory of complexity, systems are not just structural entities; they are formed in the context of forces and conditions related to the lower levels of a hierarchy and are constructed and reconstructed by the actors within these levels, undergoing constant revision. The complexity theory also conceptualizes social processes and structures in the context of time and space [19]. The present study was conducted in a local neighborhood primarily accommodating non-native residents or immigrants from deprived villages who come to work in workshops and brick kilns. This study aimed to provide a deeper understanding of the dimensions of social resilience in the residents of this neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic, in light of the complexity theory introduced by David Byrne and Gil Callaghan [19].

Methods

The present case study was conducted in the spring of 2021, using in-depth interviews and field observation in the Tawheed neighborhood of Gonabad City in eastern Iran. The research population was all people over 15 years of age living in the above-mentioned neighborhood for at least two years. In this study, a systematic sampling method with maximum variety was employed, considering the inclusion criteria. The main question of the interview was: What effect did the COVID-19 disease have on your life? Were you prepared to face such an event? Interviews continued until data saturation with 17 participants. Data saturation was when a new interview did not lead us to a new finding. Each interview lasted, on average, one and a half hours. The conversations were recorded, coded, and transcribed. To improve the rigor of the study, we followed Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria of credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability [20]. The credibility of the data was ensured by the continuous engagement of the researchers with the data. For validation of the coded texts, they were given not only to other members of the research team but also to the participants who were requested to check the correct understanding of their perceptions. Constant evaluation of the data was done to ensure dependability. Confirmability was ensured by continuous and meticulous documentation of data collection and data analysis at all stages of the study, from beginning to end. For data analysis, a directed qualitative content analysis was conducted. To this end, researchers began with a review of the existing literature to identify the key concepts or variables as primary coding categories [20]. In this research, David Byrne and Gil Callahan’s complexity approach and previous research on social resilience were used.

Results

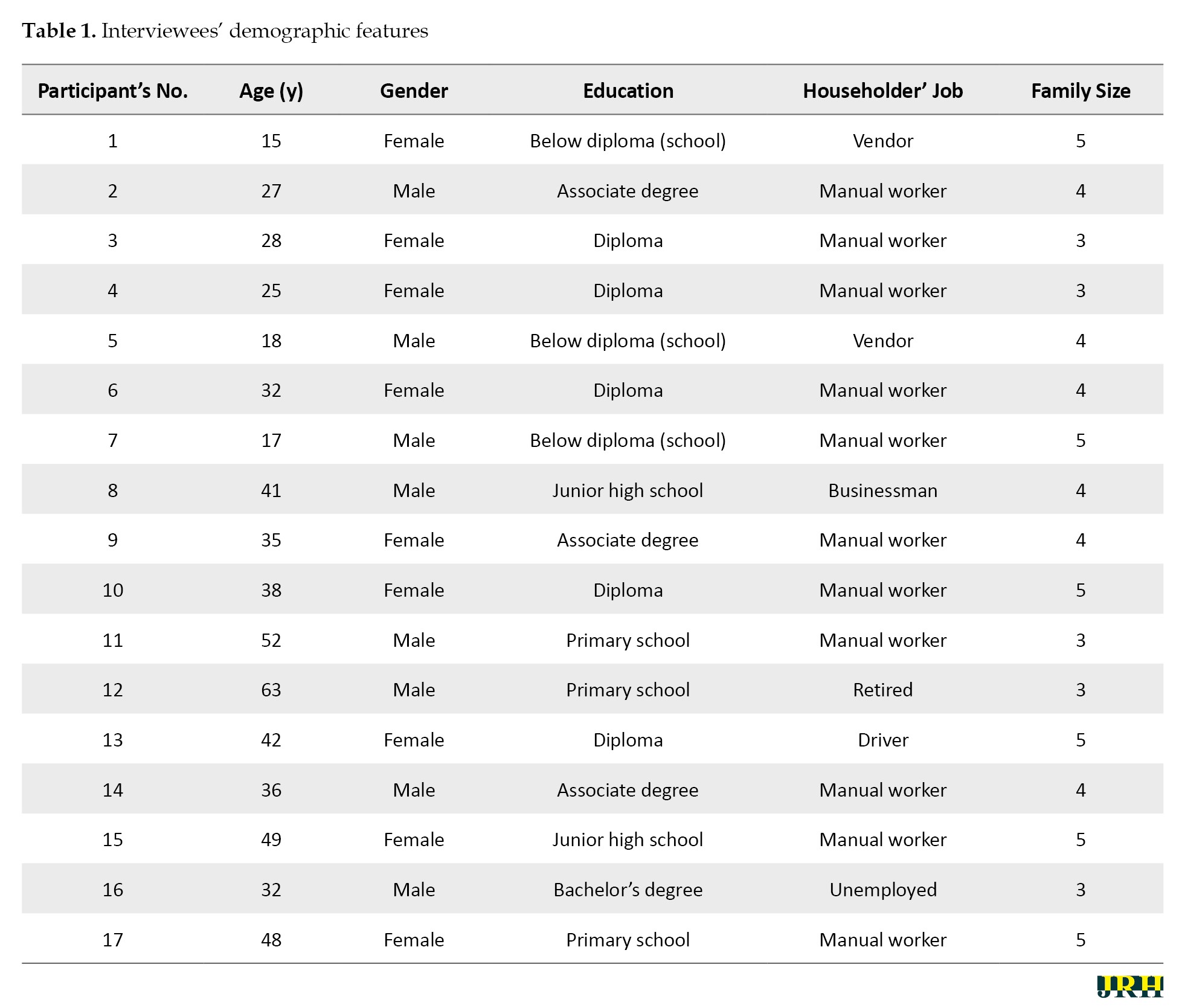

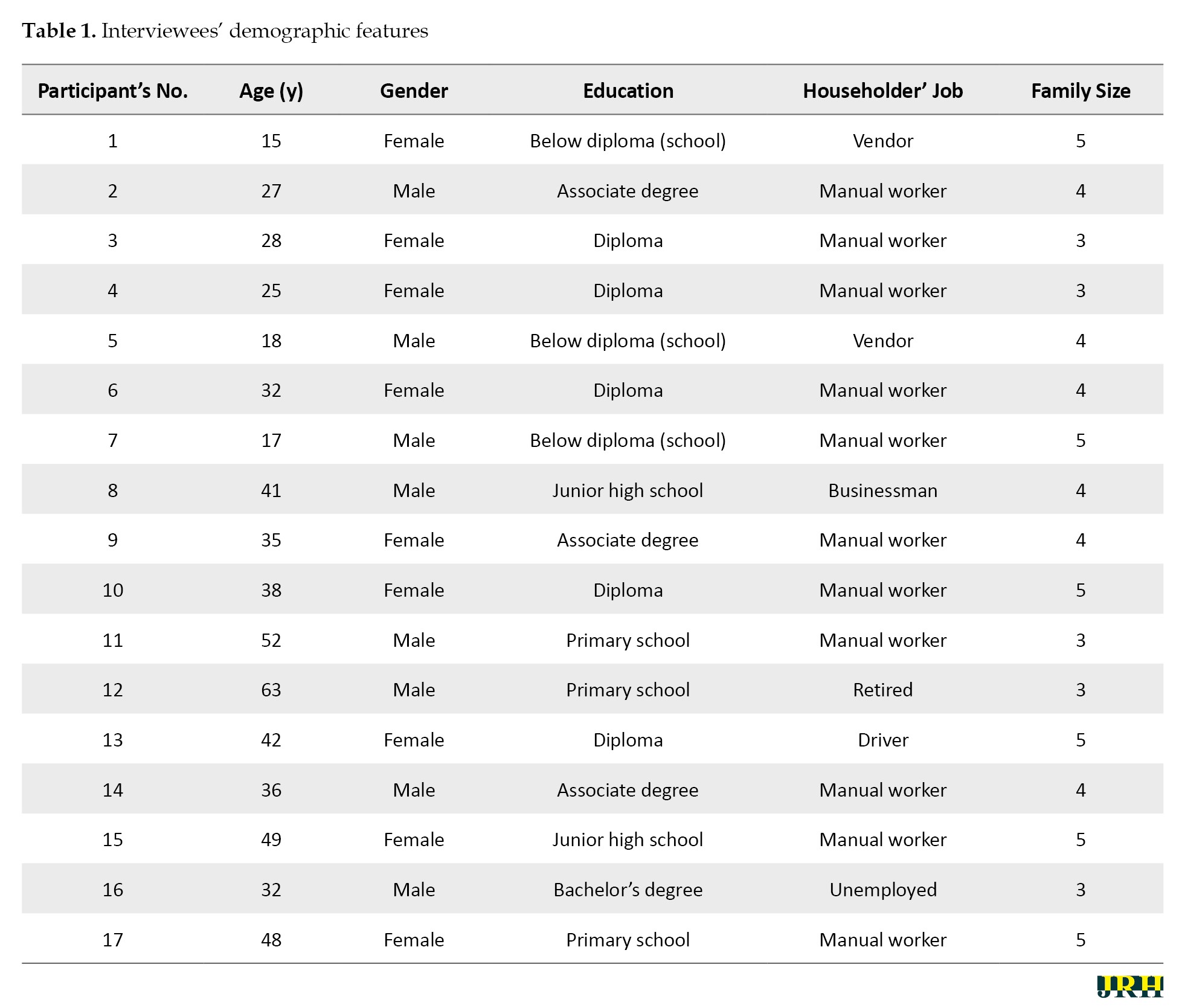

The participants in this study consisted of 17 local residents (eight men and nine women). The demographic features are summarized in Table 1.

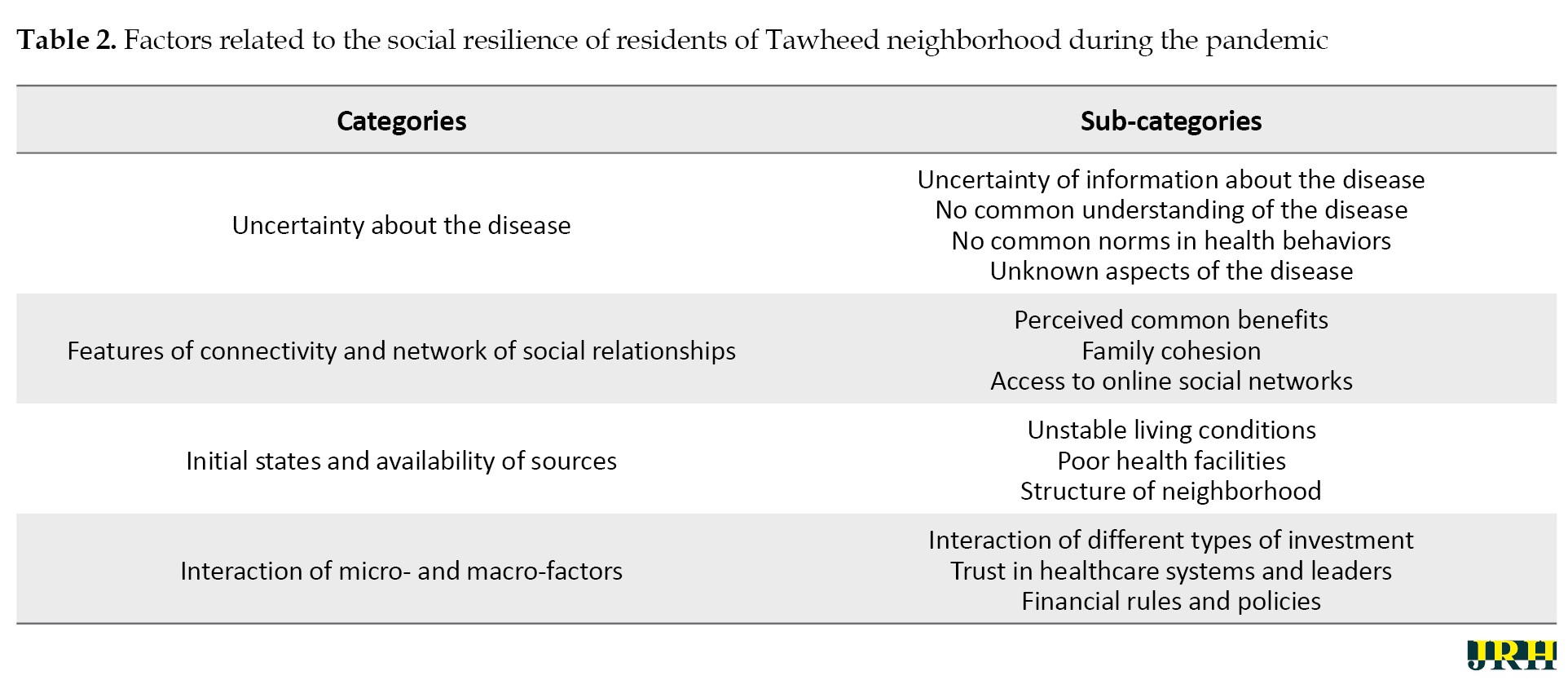

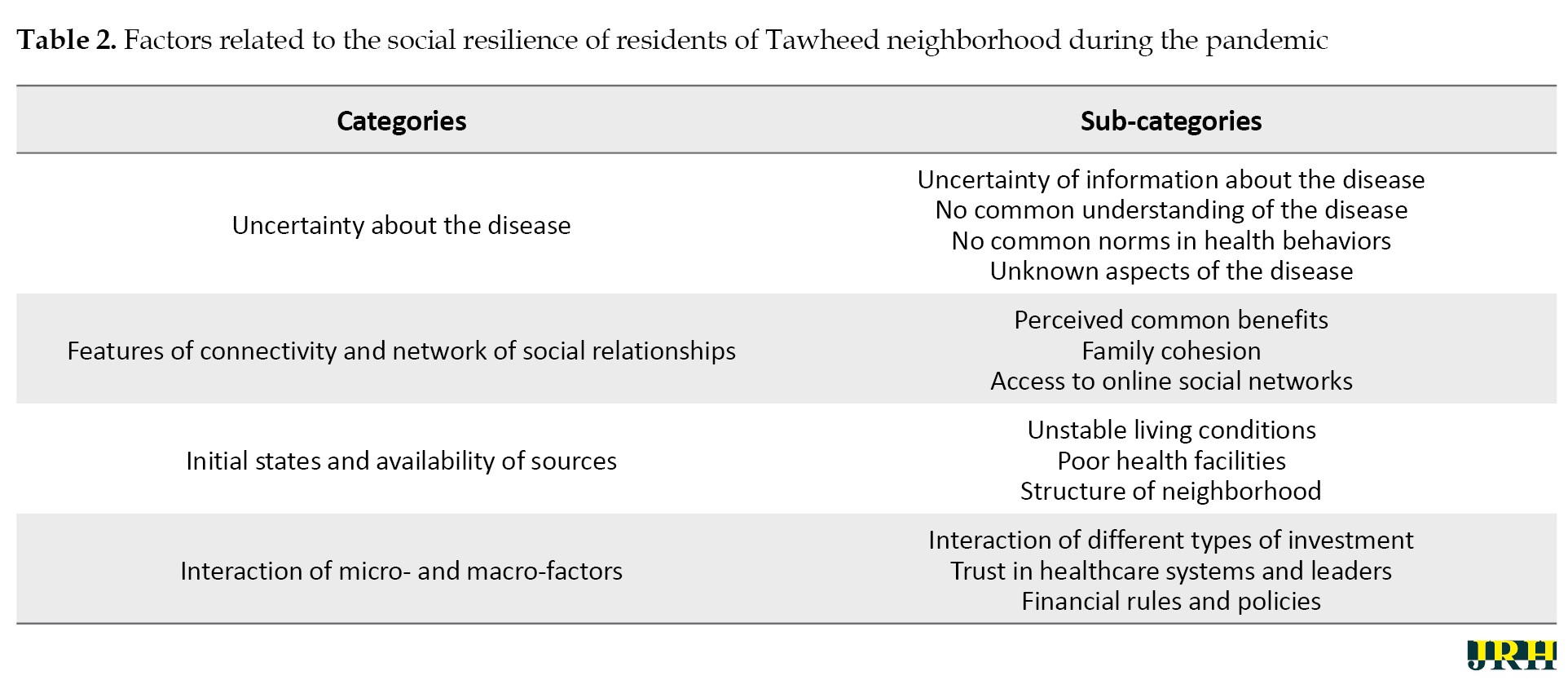

The social resilience of the residents of the Tawheed neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic was influenced by different factors. These factors were explained in light of complexity theory. A total number of four categories and 13 sub-categories were extracted (Table 2).

Uncertainty about the disease

An important feature of the social complexity theory is uncertainty about the disease. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of the disease was unknown, and the relevant news or information was scarce or misleading. For example, among the interviewees, a woman with two children said: “Everyone says something about the disease; one recommends wearing a mask, another says that masks are not good for the lungs. Some say the virus can pass through the surface of masks. Others say no. Some advice to vaccinate, some not. We are all confused” (Participant (P)#6).

This uncertainty was particularly evident in decisions and policy-making about quarantine, traffic, and public gatherings. As most residents of the local neighborhood were daily workers, the fluctuations in economic life decisions significantly disturbed them. An interviewee, a livestock worker in a nearby town, said: “When this disease emerged, I lost my job because of the traffic ban, and now I have had no income for several months” (P#16).

Another issue was the absence of any common understanding of COVID-19. The interviewees’ perceptions of the disease ranged from denial to acceptance. For instance, a young interviewee said: “They intentionally created COVID-19 and spread it in the world to make people sell their body organs” (P#14). Also, an old man said sarcastically: “I don’t take COVID-19 seriously, if God wants a person to die, he will die even if he locks himself in” (P#12). The lack of a common understanding of the disease among the residents led to disagreements on self-care norms, such as observing social distancing and wearing masks. One participant expressed displeasure: “Here, people do not comply with rules. Even the infected do not bother to visit a doctor. Though they know the virus is around, they keep going to the supermarket, the bakery, and the like. Even the Ramadan ceremonies and gatherings are held at home” (P#15). Some residents of the neighborhood strongly believed that taking addictive drugs helped them become immune to the disease and avoid infection. An interviewee said: “I saw a guy wandering the streets every day, scavenging the trash cans for plastic and cans. I asked if he was not afraid of getting infected. He said no, as he took some drugs late at night when he got home” (P#10). A female interviewee said: “Since the virus appeared, the number of drug buyers has increased. The price has gone up. What’s worse, the impurities have increased too” (P#17).

Another sub-category of uncertainty about COVID-19 was the unknown consequences of the pandemic. In complex issues, some effects manifest in the short term, while others appear in the long term. For example, an interviewee who was a school car driver said he had to leave his job for a new one because of absenteeism at school. Despite physical disability, he was doing heavy manual work. This issue may not have a significant impact on the family system at the moment, but in the long run, the adverse effects will likely emerge.

Features of connectivity and network of social relationships

The resilience of a social system depends on the connectivity features that help all elements work in the interest of the entire system and maintain resilience. In a social environment, the stakeholders’ definition of their interests and the system to which they belong is an important connecting factor [18]. In the local neighborhood studied here, people hardly agreed on any common interests. Occasionally, they even had conflicting interests, which could adversely affect their resilience during the pandemic. The residents of this neighborhood had migrated from other deprived areas and did not feel a deep sense of belonging to their new location. Most interviewees mentioned their original place of origin when they initially introduced themselves, indicating that they still felt a connection to where they came from. The conflicting interests of drug dealers during the pandemic with other residents were a primary reason for the existing tensions among the local residents. An interviewee said: “Too often during the day, strangers come to this place looking for drugs. You cannot tell whether they really want the drugs for the elderly or those infected with the virus. They scare you. You do not feel safe here anymore” (P#3).

Another connecting feature that affected people’s resilience was family cohesion. For instance, a 32-year-old woman said: “My husband doesn’t comply with health-related rules. We have had a row several times. Today, I threatened him and said that if he doesn’t wear a mask outside, I will leave home” (P#6). As the residents were almost all immigrants who had moved into this neighborhood as single families, they were now primarily facing challenges in their family bonds during the pandemic. An interviewee said: “I used to visit the village I come from every week. Now I haven’t seen my parents for two and a half months” (P#9). Since most families had a low socioeconomic status, financial support from relatives was nearly nonexistent. Concerning this issue, a woman stated: “Since the pandemic began, our income has dramatically decreased. We had to borrow from my mother-in-law. After a month, my father-in-law said we had to return the money. My husband was upset, and after a row, we decided to borrow from my siblings to return the money we owed. Now, little by little, we are returning the money we borrowed from my siblings” (P#4).

When face-to-face interactions are not possible, online social communication helps improve people’s mood [20]. Among the interviewees, except for two, the rest did not have access to online social networks. Therefore, it was not possible for them to have online social interactions to make up for face-to-face communication.

Initial state and availability of sources

In the social complexity approach, initial states are of key importance in a phenomenon [21]. The neighborhood of interest was economically poor and the residents had unstable living conditions. An interviewee said: “This part of the city seems to be abandoned. During the election, everyone made a promise to improve living conditions here. Later on, nothing was done about it” (P#16). Another interviewee said: “We do not know what to do. When we try to get a rural housing loan, they say we cannot because we are urban residents. When we try to get a loan for construction, they say we cannot as we do not live in the city, but rather in the suburbs” (P#2). Most residents were employed as daily wage workers. A woman who had suffered her husband’s long-held unemployment said: “Well, of course, if a worker stops working, he won’t be able to afford a living” (P#9). These problems seem to have made the residents more vulnerable and diminished their resilience during the pandemic.

Poor health facilities in the neighborhood, such as inappropriate urban design for directing wastewater in the streets and keeping livestock inside homes, were other issues raised by interviewees as reasons for low resilience during the pandemic. The residents felt somehow abandoned in terms of health rules and regulations in their neighborhood. For example, a woman pointed to the water stream flowing in the middle of the street, blocked with some paper towels and snack wrappers, and said: “Look, this is where we live. This water comes into my house. My little children touch it and ...” (P#10).

Another issue was the physical condition of the neighborhood and the lack of a green space, which adversely affected the resilience during the pandemic. The alleys were narrow, which made it possible to transmit the virus faster. The walls between houses were not tall and safe enough in some places. An interviewee said: “The wall of our house is so short that you can easily see or hear anyone passing the street nearby coughing. That’s why when my children are in the yard, I tell them to wear two masks” (P#3). The neighborhood also lacked a green place or a playground that could increase people’s resilience in the face of the disease. Almost all interviewees mentioned this problem.

Interaction of micro and macro factors

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is basically medical in nature, it has biological, human, and social dimensions [3]. During the pandemic, different capitals of the local residents decreased, which tremendously affected their resilience. In critical conditions, people’s social, economic, and cultural capital and their position (symbolic capital) change. Our observations showed that following a decrease in people’s occupational and financial capital, there was a decrease in social capital (trust, security), cultural capital (enjoyment of education), and physical capital (nutrition and health). A teenage girl, whose parents had gone to a distant village to sell goods (because there was no legal prohibition against buying and selling there), dropped out of school and took on household responsibilities, caring for her 5-year-old brother. This interviewee said: “The child cries every night and asks for things. Because of him, I fell behind in my studies” (P#1). A middle-aged woman with twin teenage children, who dropped out of school during the pandemic due to a lack of facilities for online education, commented: “It’s been about a year since they have left school. They fell behind others, so I don’t think it’s of any use to go to school later” (P#15).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience and adaptation to new conditions, people’s trust in healthcare systems, authorities, and leaders were strongly needed. Our findings in the target neighborhood revealed a lack of trust in governing institutions. An important reason for this is the sense of isolation, abandonment, and lacking connection between local residents and the rest of society. An interviewee pointed to a dried tree in front of his house with disbelief and said: “Look, this tree was sprayed two nights ago; it died soon after. We are not sure what the content of these detergents and disinfectants is. I’d rather die. I’ll never get any of those sanitizing liquids or gels” (P#11).

There are also financial policies, such as lowering taxes and giving bank loans that could increase people’s resilience during the pandemic. An interviewee said: “Because of a 4-million debt, I had a bounced check for 70 million tomans. Now they even closed my subsidy account for the same reason. They closed it, and there is no law to prevent the check from being executed, or at least to delay the closure of the account to give some more time to the one in debt (P#8).

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the social resilience of people living in a poor neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic in light of the complexity theory. The social resilience of the residents of the Tawheed neighborhood during the pandemic was found to be influenced by four causal categories: Uncertainty about the disease, connectivity features and network of social relations, initial state and access to resources, and the interaction of micro and macro factors. In other studies, the COVID-19 pandemic has been also considered a major issue marked by complex social dimensions, long-term nature, uncertain time frames, lack of a comprehensive solution, and unclear criteria [22]. We believe the literature provides a deeper and multi-dimensional view. The complexity theory relies on the systemic theory and perceives facts as interwoven and multi-layered. In this perspective, systems are not merely structural entities; rather, they are created by actors and are constantly revised. The complexity theory also conceptualizes social processes and structures within time and place constraints. We used this theory to better delve into social resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we focused on the properties of the neighborhood, the spatial features, and what, in the long run, had not managed to lead to a common identity, but instead had resulted in social conflicts.

The present findings showed that uncertainty about COVID-19 had affected people’s resilience. The participants were confused and uncertain about the diagnosis of the disease and the ways to cope with it. Other studies reported that medical advice during the pandemic, despite being very helpful, was highly ambiguous and worrisome. Also, the participants emphasized their perceived uncertainty about the long-term political and social effects of the pandemic [21]. A study has pointed out the ambiguity and confusion about career paths [23]. Concerning quarantine rules and regulations and the long-term adverse effects, several issues were raised, such as unemployment, bankruptcy, mental health issues, domestic violence, failed marriages, and civil disobedience [22]. The existing literature shows that the concept of uncertainty has been scarcely addressed in policy-making while providing more resilient solutions requires greater attention to the issue of uncertainty [24].

The findings also raised the importance of a network of social relationships as a factor affecting social resilience. In the complexity theory, social relations act as a connectivity feature that enables functioning based on systemic benefits and maintaining resilience in the system [18]. The network of social relations, which includes the cohesion between family members, friends, neighbors, and colleagues, was weakened during the COVID-19 pandemic due to social distancing [25]. During the pandemic, some local communities coped with the disease better by strengthening a sense of unity and belonging to the group and by recalling themes, such as “we are all together” [22]. A strong collective and local identity is one of the resources and opportunities for resilience [26]. The residents of the Tawheed neighborhood, who had moved there from three different origins, had a weak sense of local belonging, which weakened their collective resilience in the face of crises. A related study showed that integration in community networks creates more diversity in resilience strategies, which can help improve and survive the household in critical conditions [27]. Another study confirmed the importance of social capital, norms, and trust in creating harmony, self-organization, and adaptability to the new context [28]. Our study also showed that due to their low socioeconomic status, people were often deprived of online social communication. Although online social communication could effectively replace face-to-face interactions in certain situations and protect people from social isolation [20], the poor lacked the necessary facilities.

As the present findings showed, the local residents’ initial state of life w::as char::acterized by unstable livelihood, poor health facilities, poor physical structure of the neighborhood, and a lack of green space, which all adversely affected resilience in the face of the pandemic. According to the complexity theory, initial states and chance are of key importance in any experience. The pandemic was a shocking experience to which different nations and populations responded differently according to specific prior conditions [21]. A study showed that some families suffered more from the negative effects of the disease due to their previous circumstances, such as low income and marginalization [29].

In other studies, abundant resources and facilities have been considered effective for appropriately responding to a crisis and promoting social resilience [30, 31]. Health facilities and the physical condition of a region are important in social resilience, which was in poor condition in the Tawheed neighborhood. Also, this neighborhood lacked a park and sports recreation space. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of architecture and urban management became more apparent than before [32]. For example, there is evidence that green areas increase social resilience during times of physical isolation [33]. Social distancing also necessitated access to open spaces and suitable housing [22]. According to social complexity theory, if the key causal categories change adequately, fundamental changes may occur in a short time [19]. In this neighborhood, for instance, if suitable open spaces were created for the residents, their sense of self-esteem and compliance with self-care norms and quarantine measures during the pandemic could improve.

The present study also showed that social resilience resulted from different micro- and macro-level factors [19]. Resilience should also be considered a social process in relation to the social context [27]. The resilience of any system results from mutual relationships between system components at different scales of time and place [34]. Resilience has different dimensions and its increase or decrease in one dimension can affect other dimensions. At the macro level, trust in leaders and authorities played a decisive role in disease-adaptive behaviors. As the existing literature indicates, trust in political leaders and the legitimacy of the plans they develop positively correlate with resilience [35]. The government’s support systems were also important predictors of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the present study, except for one participant who managed to secure an unemployment loan, the others did not benefit from any supportive plans. Some research conducted in the Philippines showed that the government’s systematic interventions could mitigate the negative economic effects on low socioeconomic classes [36]. Another study showed that the lack of government support in a three-month period during the pandemic significantly increased the poverty rate of the residents of a neighborhood [37]. The findings of a systematic review revealed that social protection programs serve as flexible and strategic means of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic [38].

Conclusion

The social resilience of the Tawheed neighborhood during the pandemic was influenced by different factors at the micro and macro levels interacting with each other. It was largely affected by the initial state of people’s living conditions. The initial states and pre-existing capacities largely determined the level of resilience and adaptation to new conditions.

During the pandemic, the interconnected network of human agents aimed at strengthening adaptive collective actions (including family, kinship, and local relationships) was weak among the local residents. It appears that the government should implement reconnecting interventions based on the native potentials of each region and pay attention to the existing uncertainties in the planning process.

The pandemic experience demonstrated that human problems are intertwined, and individual responses are insufficient to address them. Considering the importance of resilience in controlling pandemics, we attempted to identify its components in a relatively deprived neighborhood. It is suggested that future studies use the comparative qualitative analysis for a more detailed investigation.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran (Code: IR.GMU.REC.1400.024).

Funding

This research was supported by the Deputy for Research, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Vajihe Armanmehr, Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh; Data collection: Vajihe Armanmehr; Data analysis: Vajihe Armanmehr, Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh; Writing the original draft: Vajihe Armanmehr, Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the residents of the Tawheed neighborhood of Gonabad City who participated in this study.

References

The COVID-19 pandemic, officially declared a crisis by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1] on March 11, 2020, brought about multidimensional changes to people’s lives, and the policymakers did not have enough time to respond and adapt to the situation [2]. This pandemic had a complex and multifaceted nature marked by biological, human, and social sub-systems (e.g. public opinion, network media, and government credibility) [3, 4]. People in different countries implemented different measures to respond to this crisis, reflecting their different levels of resilience [5]. Resilience is one of the goals of the United Nations (UN)’ 2030 agenda, which encompasses the core concept of adaptation—a concept that refers to the limits of environmental, socio-political, and cultural compatibility [6]. Social resilience is defined as the ability of social entities and social mechanisms to effectively anticipate, mitigate, and cope with disasters, as well as to engage in recovery activities that minimize social disruptions and reduce the impact of future disasters [7].

Various factors can lead to resilience and cause society members to be more or less affected by a crisis [8]. Information and awareness, sense of identity, financial capital, lifestyle, social partnerships, and economic and social incentives can increase the level of resilience [9]. As experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, joint collective activities and cultural agreement on common values were among the most important aspects of resilience. The provision of public services and adequate access to services [10] was also an important issue [10, 11]. Vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, children, and deprived and marginalized classes demonstrated less social resilience due to limited access to resources and facilities. In addition, people with informal work and daily wages constituted a major at-risk group [12]. Evidence indicates that some geographic regions exhibit greater resilience while others show less during critical conditions [13]. This issue was also visible in the COVID-19 pandemic, as some regions faced more challenges [14].

Since the COVID-19 pandemic was raised as a complex issue [15], the social complexity approach is appropriate to explore the concept of resilience during the pandemic. The meanings and functions of resilience lie in larger social, economic, and political contexts [16]. Only by acknowledging the holistic and complex aspects of the pandemic and avoiding simplistic linear solutions can this experience be adequately and insightfully understood [17]. Unlike biophysical systems, the resilience of a social system depends on the fact that predicting something about the future and sharing it with all actors/agents in the same system can motivate them to participate more. It indicates the role of awareness of agency within these systems. A considerable point is that agency can influence everything, making it related to power. However, actors/agents do not operate in a vacuum; some possess more power to effect change while others have less. Social resilience results from the interactions among individual, collective, and institutional actors [18].

The complexity theory is based on a systemic perspective. Reality is complex and nested, which means its scientific processes cannot be explained by a single cause. In the theory of complexity, systems are not just structural entities; they are formed in the context of forces and conditions related to the lower levels of a hierarchy and are constructed and reconstructed by the actors within these levels, undergoing constant revision. The complexity theory also conceptualizes social processes and structures in the context of time and space [19]. The present study was conducted in a local neighborhood primarily accommodating non-native residents or immigrants from deprived villages who come to work in workshops and brick kilns. This study aimed to provide a deeper understanding of the dimensions of social resilience in the residents of this neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic, in light of the complexity theory introduced by David Byrne and Gil Callaghan [19].

Methods

The present case study was conducted in the spring of 2021, using in-depth interviews and field observation in the Tawheed neighborhood of Gonabad City in eastern Iran. The research population was all people over 15 years of age living in the above-mentioned neighborhood for at least two years. In this study, a systematic sampling method with maximum variety was employed, considering the inclusion criteria. The main question of the interview was: What effect did the COVID-19 disease have on your life? Were you prepared to face such an event? Interviews continued until data saturation with 17 participants. Data saturation was when a new interview did not lead us to a new finding. Each interview lasted, on average, one and a half hours. The conversations were recorded, coded, and transcribed. To improve the rigor of the study, we followed Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria of credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability [20]. The credibility of the data was ensured by the continuous engagement of the researchers with the data. For validation of the coded texts, they were given not only to other members of the research team but also to the participants who were requested to check the correct understanding of their perceptions. Constant evaluation of the data was done to ensure dependability. Confirmability was ensured by continuous and meticulous documentation of data collection and data analysis at all stages of the study, from beginning to end. For data analysis, a directed qualitative content analysis was conducted. To this end, researchers began with a review of the existing literature to identify the key concepts or variables as primary coding categories [20]. In this research, David Byrne and Gil Callahan’s complexity approach and previous research on social resilience were used.

Results

The participants in this study consisted of 17 local residents (eight men and nine women). The demographic features are summarized in Table 1.

The social resilience of the residents of the Tawheed neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic was influenced by different factors. These factors were explained in light of complexity theory. A total number of four categories and 13 sub-categories were extracted (Table 2).

Uncertainty about the disease

An important feature of the social complexity theory is uncertainty about the disease. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of the disease was unknown, and the relevant news or information was scarce or misleading. For example, among the interviewees, a woman with two children said: “Everyone says something about the disease; one recommends wearing a mask, another says that masks are not good for the lungs. Some say the virus can pass through the surface of masks. Others say no. Some advice to vaccinate, some not. We are all confused” (Participant (P)#6).

This uncertainty was particularly evident in decisions and policy-making about quarantine, traffic, and public gatherings. As most residents of the local neighborhood were daily workers, the fluctuations in economic life decisions significantly disturbed them. An interviewee, a livestock worker in a nearby town, said: “When this disease emerged, I lost my job because of the traffic ban, and now I have had no income for several months” (P#16).

Another issue was the absence of any common understanding of COVID-19. The interviewees’ perceptions of the disease ranged from denial to acceptance. For instance, a young interviewee said: “They intentionally created COVID-19 and spread it in the world to make people sell their body organs” (P#14). Also, an old man said sarcastically: “I don’t take COVID-19 seriously, if God wants a person to die, he will die even if he locks himself in” (P#12). The lack of a common understanding of the disease among the residents led to disagreements on self-care norms, such as observing social distancing and wearing masks. One participant expressed displeasure: “Here, people do not comply with rules. Even the infected do not bother to visit a doctor. Though they know the virus is around, they keep going to the supermarket, the bakery, and the like. Even the Ramadan ceremonies and gatherings are held at home” (P#15). Some residents of the neighborhood strongly believed that taking addictive drugs helped them become immune to the disease and avoid infection. An interviewee said: “I saw a guy wandering the streets every day, scavenging the trash cans for plastic and cans. I asked if he was not afraid of getting infected. He said no, as he took some drugs late at night when he got home” (P#10). A female interviewee said: “Since the virus appeared, the number of drug buyers has increased. The price has gone up. What’s worse, the impurities have increased too” (P#17).

Another sub-category of uncertainty about COVID-19 was the unknown consequences of the pandemic. In complex issues, some effects manifest in the short term, while others appear in the long term. For example, an interviewee who was a school car driver said he had to leave his job for a new one because of absenteeism at school. Despite physical disability, he was doing heavy manual work. This issue may not have a significant impact on the family system at the moment, but in the long run, the adverse effects will likely emerge.

Features of connectivity and network of social relationships

The resilience of a social system depends on the connectivity features that help all elements work in the interest of the entire system and maintain resilience. In a social environment, the stakeholders’ definition of their interests and the system to which they belong is an important connecting factor [18]. In the local neighborhood studied here, people hardly agreed on any common interests. Occasionally, they even had conflicting interests, which could adversely affect their resilience during the pandemic. The residents of this neighborhood had migrated from other deprived areas and did not feel a deep sense of belonging to their new location. Most interviewees mentioned their original place of origin when they initially introduced themselves, indicating that they still felt a connection to where they came from. The conflicting interests of drug dealers during the pandemic with other residents were a primary reason for the existing tensions among the local residents. An interviewee said: “Too often during the day, strangers come to this place looking for drugs. You cannot tell whether they really want the drugs for the elderly or those infected with the virus. They scare you. You do not feel safe here anymore” (P#3).

Another connecting feature that affected people’s resilience was family cohesion. For instance, a 32-year-old woman said: “My husband doesn’t comply with health-related rules. We have had a row several times. Today, I threatened him and said that if he doesn’t wear a mask outside, I will leave home” (P#6). As the residents were almost all immigrants who had moved into this neighborhood as single families, they were now primarily facing challenges in their family bonds during the pandemic. An interviewee said: “I used to visit the village I come from every week. Now I haven’t seen my parents for two and a half months” (P#9). Since most families had a low socioeconomic status, financial support from relatives was nearly nonexistent. Concerning this issue, a woman stated: “Since the pandemic began, our income has dramatically decreased. We had to borrow from my mother-in-law. After a month, my father-in-law said we had to return the money. My husband was upset, and after a row, we decided to borrow from my siblings to return the money we owed. Now, little by little, we are returning the money we borrowed from my siblings” (P#4).

When face-to-face interactions are not possible, online social communication helps improve people’s mood [20]. Among the interviewees, except for two, the rest did not have access to online social networks. Therefore, it was not possible for them to have online social interactions to make up for face-to-face communication.

Initial state and availability of sources

In the social complexity approach, initial states are of key importance in a phenomenon [21]. The neighborhood of interest was economically poor and the residents had unstable living conditions. An interviewee said: “This part of the city seems to be abandoned. During the election, everyone made a promise to improve living conditions here. Later on, nothing was done about it” (P#16). Another interviewee said: “We do not know what to do. When we try to get a rural housing loan, they say we cannot because we are urban residents. When we try to get a loan for construction, they say we cannot as we do not live in the city, but rather in the suburbs” (P#2). Most residents were employed as daily wage workers. A woman who had suffered her husband’s long-held unemployment said: “Well, of course, if a worker stops working, he won’t be able to afford a living” (P#9). These problems seem to have made the residents more vulnerable and diminished their resilience during the pandemic.

Poor health facilities in the neighborhood, such as inappropriate urban design for directing wastewater in the streets and keeping livestock inside homes, were other issues raised by interviewees as reasons for low resilience during the pandemic. The residents felt somehow abandoned in terms of health rules and regulations in their neighborhood. For example, a woman pointed to the water stream flowing in the middle of the street, blocked with some paper towels and snack wrappers, and said: “Look, this is where we live. This water comes into my house. My little children touch it and ...” (P#10).

Another issue was the physical condition of the neighborhood and the lack of a green space, which adversely affected the resilience during the pandemic. The alleys were narrow, which made it possible to transmit the virus faster. The walls between houses were not tall and safe enough in some places. An interviewee said: “The wall of our house is so short that you can easily see or hear anyone passing the street nearby coughing. That’s why when my children are in the yard, I tell them to wear two masks” (P#3). The neighborhood also lacked a green place or a playground that could increase people’s resilience in the face of the disease. Almost all interviewees mentioned this problem.

Interaction of micro and macro factors

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is basically medical in nature, it has biological, human, and social dimensions [3]. During the pandemic, different capitals of the local residents decreased, which tremendously affected their resilience. In critical conditions, people’s social, economic, and cultural capital and their position (symbolic capital) change. Our observations showed that following a decrease in people’s occupational and financial capital, there was a decrease in social capital (trust, security), cultural capital (enjoyment of education), and physical capital (nutrition and health). A teenage girl, whose parents had gone to a distant village to sell goods (because there was no legal prohibition against buying and selling there), dropped out of school and took on household responsibilities, caring for her 5-year-old brother. This interviewee said: “The child cries every night and asks for things. Because of him, I fell behind in my studies” (P#1). A middle-aged woman with twin teenage children, who dropped out of school during the pandemic due to a lack of facilities for online education, commented: “It’s been about a year since they have left school. They fell behind others, so I don’t think it’s of any use to go to school later” (P#15).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience and adaptation to new conditions, people’s trust in healthcare systems, authorities, and leaders were strongly needed. Our findings in the target neighborhood revealed a lack of trust in governing institutions. An important reason for this is the sense of isolation, abandonment, and lacking connection between local residents and the rest of society. An interviewee pointed to a dried tree in front of his house with disbelief and said: “Look, this tree was sprayed two nights ago; it died soon after. We are not sure what the content of these detergents and disinfectants is. I’d rather die. I’ll never get any of those sanitizing liquids or gels” (P#11).

There are also financial policies, such as lowering taxes and giving bank loans that could increase people’s resilience during the pandemic. An interviewee said: “Because of a 4-million debt, I had a bounced check for 70 million tomans. Now they even closed my subsidy account for the same reason. They closed it, and there is no law to prevent the check from being executed, or at least to delay the closure of the account to give some more time to the one in debt (P#8).

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the social resilience of people living in a poor neighborhood during the COVID-19 pandemic in light of the complexity theory. The social resilience of the residents of the Tawheed neighborhood during the pandemic was found to be influenced by four causal categories: Uncertainty about the disease, connectivity features and network of social relations, initial state and access to resources, and the interaction of micro and macro factors. In other studies, the COVID-19 pandemic has been also considered a major issue marked by complex social dimensions, long-term nature, uncertain time frames, lack of a comprehensive solution, and unclear criteria [22]. We believe the literature provides a deeper and multi-dimensional view. The complexity theory relies on the systemic theory and perceives facts as interwoven and multi-layered. In this perspective, systems are not merely structural entities; rather, they are created by actors and are constantly revised. The complexity theory also conceptualizes social processes and structures within time and place constraints. We used this theory to better delve into social resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we focused on the properties of the neighborhood, the spatial features, and what, in the long run, had not managed to lead to a common identity, but instead had resulted in social conflicts.

The present findings showed that uncertainty about COVID-19 had affected people’s resilience. The participants were confused and uncertain about the diagnosis of the disease and the ways to cope with it. Other studies reported that medical advice during the pandemic, despite being very helpful, was highly ambiguous and worrisome. Also, the participants emphasized their perceived uncertainty about the long-term political and social effects of the pandemic [21]. A study has pointed out the ambiguity and confusion about career paths [23]. Concerning quarantine rules and regulations and the long-term adverse effects, several issues were raised, such as unemployment, bankruptcy, mental health issues, domestic violence, failed marriages, and civil disobedience [22]. The existing literature shows that the concept of uncertainty has been scarcely addressed in policy-making while providing more resilient solutions requires greater attention to the issue of uncertainty [24].

The findings also raised the importance of a network of social relationships as a factor affecting social resilience. In the complexity theory, social relations act as a connectivity feature that enables functioning based on systemic benefits and maintaining resilience in the system [18]. The network of social relations, which includes the cohesion between family members, friends, neighbors, and colleagues, was weakened during the COVID-19 pandemic due to social distancing [25]. During the pandemic, some local communities coped with the disease better by strengthening a sense of unity and belonging to the group and by recalling themes, such as “we are all together” [22]. A strong collective and local identity is one of the resources and opportunities for resilience [26]. The residents of the Tawheed neighborhood, who had moved there from three different origins, had a weak sense of local belonging, which weakened their collective resilience in the face of crises. A related study showed that integration in community networks creates more diversity in resilience strategies, which can help improve and survive the household in critical conditions [27]. Another study confirmed the importance of social capital, norms, and trust in creating harmony, self-organization, and adaptability to the new context [28]. Our study also showed that due to their low socioeconomic status, people were often deprived of online social communication. Although online social communication could effectively replace face-to-face interactions in certain situations and protect people from social isolation [20], the poor lacked the necessary facilities.

As the present findings showed, the local residents’ initial state of life w::as char::acterized by unstable livelihood, poor health facilities, poor physical structure of the neighborhood, and a lack of green space, which all adversely affected resilience in the face of the pandemic. According to the complexity theory, initial states and chance are of key importance in any experience. The pandemic was a shocking experience to which different nations and populations responded differently according to specific prior conditions [21]. A study showed that some families suffered more from the negative effects of the disease due to their previous circumstances, such as low income and marginalization [29].

In other studies, abundant resources and facilities have been considered effective for appropriately responding to a crisis and promoting social resilience [30, 31]. Health facilities and the physical condition of a region are important in social resilience, which was in poor condition in the Tawheed neighborhood. Also, this neighborhood lacked a park and sports recreation space. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of architecture and urban management became more apparent than before [32]. For example, there is evidence that green areas increase social resilience during times of physical isolation [33]. Social distancing also necessitated access to open spaces and suitable housing [22]. According to social complexity theory, if the key causal categories change adequately, fundamental changes may occur in a short time [19]. In this neighborhood, for instance, if suitable open spaces were created for the residents, their sense of self-esteem and compliance with self-care norms and quarantine measures during the pandemic could improve.

The present study also showed that social resilience resulted from different micro- and macro-level factors [19]. Resilience should also be considered a social process in relation to the social context [27]. The resilience of any system results from mutual relationships between system components at different scales of time and place [34]. Resilience has different dimensions and its increase or decrease in one dimension can affect other dimensions. At the macro level, trust in leaders and authorities played a decisive role in disease-adaptive behaviors. As the existing literature indicates, trust in political leaders and the legitimacy of the plans they develop positively correlate with resilience [35]. The government’s support systems were also important predictors of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the present study, except for one participant who managed to secure an unemployment loan, the others did not benefit from any supportive plans. Some research conducted in the Philippines showed that the government’s systematic interventions could mitigate the negative economic effects on low socioeconomic classes [36]. Another study showed that the lack of government support in a three-month period during the pandemic significantly increased the poverty rate of the residents of a neighborhood [37]. The findings of a systematic review revealed that social protection programs serve as flexible and strategic means of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic [38].

Conclusion

The social resilience of the Tawheed neighborhood during the pandemic was influenced by different factors at the micro and macro levels interacting with each other. It was largely affected by the initial state of people’s living conditions. The initial states and pre-existing capacities largely determined the level of resilience and adaptation to new conditions.

During the pandemic, the interconnected network of human agents aimed at strengthening adaptive collective actions (including family, kinship, and local relationships) was weak among the local residents. It appears that the government should implement reconnecting interventions based on the native potentials of each region and pay attention to the existing uncertainties in the planning process.

The pandemic experience demonstrated that human problems are intertwined, and individual responses are insufficient to address them. Considering the importance of resilience in controlling pandemics, we attempted to identify its components in a relatively deprived neighborhood. It is suggested that future studies use the comparative qualitative analysis for a more detailed investigation.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran (Code: IR.GMU.REC.1400.024).

Funding

This research was supported by the Deputy for Research, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Vajihe Armanmehr, Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh; Data collection: Vajihe Armanmehr; Data analysis: Vajihe Armanmehr, Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh; Writing the original draft: Vajihe Armanmehr, Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the residents of the Tawheed neighborhood of Gonabad City who participated in this study.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2020 March 11]. Available from: [Link]

- Bamir M, Sadeghi R. COVID-19 and the challenges to the healthcare system in Iran. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences. 2023; 12(1):58-9. [DOI:10.34172/jqr.2023.09]

- Azimi R. From reality to social construction: A look at Corona and its implications for the health system. Journal of Research in Psychological Health. 2020; 14(1):130-42. [DOI:10.52547/rph.14.1.130]

- Jia S, Li Y, Fang T. System dynamics analysis of COVID-19 prevention and control strategies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 2022; 29(3):3944-57. [DOI:10.1007/s11356-021-15902-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lenton TM, Boulton CA, Scheffer M. Resilience of countries to COVID-19 correlated with trust. Scientific Reports. 2022; 12(1):75. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-03358-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zabaniotou A. A systemic approach to resilience and ecological sustainability during the COVID-19 pandemic: Human, societal, and ecological health as a system-wide emergent property in the Anthropocene. Global Transitions. 2020; 2:116-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Alizadeh H, Sharifi A. Analysis of the state of social resilience among different socio-demographic groups during the COVID- 19 pandemic. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021; 64:102514. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102514] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Adeniran AS, Aboyeji AP, Fawole AA, Balogun OR, Adesina KT, Adeniran PI. Male partner's role during pregnancy, labour and delivery: expectations of pregnant women in Nigeria. International Journal of Health Sciences. 2015; 9(3):305-13. [DOI:10.12816/0024697] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Seidali A, Namazi N. [Study of antagonistic properties of lactobacilli isolated from healthy baby stools on growth of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa of nosocomial origin (Persian)]. Pajoohandeh Journal. 2016; 20(6):315-9. [Link]

- Ratten V. Coronavirus (covid-19) and social value co-creation. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2022; 42(3/4):222-31. [DOI:10.1108/IJSSP-06-2020-0237]

- Babaei F, Aghajani M, Estambolichi L, Joshari M, Mazaheri Z, Kykhosravi F, et al. [Study of the promotion of normal delivery program in government hospitals in line with the health transformation plan and its achievements (Persian)]. Hakim 2017; 20(1):44-53. [Link]

- Das G. 136 million jobs at risk in post-corona India [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2020 March 31]. Available from: [Link]

- Parés M, Blanco I, Fernández C. Facing the great recession in deprived urban areas: How civic capacity contributes to neighborhood resilience. City & Community. 2018; 17(1):65-86. [DOI:10.1111/cico.12287]

- Mukherjee S, Dasgupta P, Chakraborty M, Biswas G, Mukherjee S. Vulnerability of major indian states due to COVID-19 spread and lockdown. Kolkata: Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata; 2020. [Link]

- Franke VC, Elliott CN. Optimism and social resilience: Social isolation, meaninglessness, trust, and empathy in times of covid-19. Societies. 2021; 11(2):35. [DOI:10.3390/soc11020035]

- Henly-Shepard S, Anderson C, Burnett K, Cox LJ, Kittinger JN, Ka’aumoana Ma. Quantifying household social resilience: a place-based approach in a rapidly transforming community. Natural Hazards. 2015; 75(1):343-63. [DOI:10.1007/s11069-014-1328-8]

- Angeli F, Montefusco A. Sensemaking and learning during the Covid-19 pandemic: A complex adaptive systems perspective on policy decision-making. World Development. 2020; 136:105106. [DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105106] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cardinale I. Vulnerability, resilience and ‘systemic interest’: A connectivity approach. Networks and Spatial Economics. 2019; 22:691-707. [Link]

- Byrne D, Callaghan G. Complexity theory and the social sciences: The state of the art. London: Routledge; 2013. [DOI:10.4324/9780203519585]

- Marinucci M, Pancani L, Aureli N, Riva P. Online social connections as surrogates of face-to-face interactions: A longitudinal study under Covid-19 isolation. Computers in Human Behavior. 2022; 128:107102. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2021.107102]

- Harrison NE, Geyer R. Governing complexity in the 21st century. London: Routledge; 2021. [DOI:10.4324/9780429296956]

- Menzies J, Raskovic MM. Taming COVID-19 through social resilience: A meta-capability policy framework from Australia and New Zealand. AIB Insights. 2020; 20(3):1-5. [DOI:10.46697/001c.18165]

- Sadeghi A, Asgari Z, Azizkhani R, Azimi Meibody A, Akhoundi Meybodi Z. [Explaining post-traumatic growth during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative research (Persian)]. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences. 2022; 11(1):35-41. [Link]

- Liu Y, Froese FJ. Crisis management, global challenges, and sustainable development from an Asian perspective. Asian Business & Management. 2020; 19(3):271–6. [DOI:10.1057/s41291-020-00119-x] [PMCID]

- Naser AY, Al-Hadithi HT, Dahmash EZ, Alwafi H, Alwan SS, Abdullah ZA. The effect of the 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak on social relationships: A cross-sectional study in Jordan. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2021; 67(6):664-71. [DOI:10.1177/0020764020966631] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Templeton A, Guven ST, Hoerst C, Vestergren S, Davidson L, Ballentyne S, et al. Inequalities and identity processes in crises: Recommendations for facilitating safe response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The British Journal of Social Psychology. 2020; 59(3):674-85. [DOI:10.1111/bjso.12400] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Revilla JC, Martín P, de Castro C. The reconstruction of resilience as a social and collective phenomenon: Poverty and coping capacity during the economic crisis. European Societies. 2018; 20(1):89-110. [DOI:10.1080/14616696.2017.1346195]

- Fraccascia L, Giannoccaro I, Albino V. Resilience of complex systems: state of the art and directions for future research. Complexity. 2018; 2018:1-44. [DOI:10.1155/2018/3421529]

- Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Psychologist. 2020; 75(5):631-43. [DOI:10.1037/amp0000660] [PMID]

- Alizadeh H, Sharifi A. Social resilience promotion factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Urmia, Iran. Urban Science. 2022; 6(1):14. [DOI:10.3390/urbansci6010014]

- Saja AA, Goonetilleke A, Teo M, Ziyath AM. A critical review of social resilience assessment frameworks in disaster management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2019; 35:101096. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101096]

- Fezi BA. Health engaged architecture in the context of COVID-19. Journal of Green Building. 2020; 15(2):185-212. [DOI:10.3992/1943-4618.15.2.185]

- Joshi N, Wende W. Physically apart but socially connected: Lessons in social resilience from community gardening during the COVID-19 pandemic. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2022; 223:104418. [DOI:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104418] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Deal B, Gu Y. Resilience thinking meets social-ecological systems (sess): A general framework for resilient planning support systems (psss). Journal of Digital Landscape Architecture. 2018; 3:200-7. [Link]

- Fernández-Prados JS, Lozano-Díaz A, Muyor-Rodríguez J. Factors explaining social resilience against COVID-19: The case of Spain. European Societies. 2021; 23(sup1):S111-S21. [DOI:10.1080/14616696.2020.1818113]

- Bhowmik D. COVID-19: Recession, poverty and inequality and redistribution. International Journal on Recent Trends in Business and Tourism. 2021; 5(1):11-21. [DOI:10.31674/ijrtbt.2021.v05i01.003]

- Martin A, Markhvida M, Hallegatte S, Walsh B. Socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 on household consumption and poverty. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change. 2020; 4(3):453-79. [DOI:10.1007/s41885-020-00070-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Abdoul-Azize HT, El Gamil R. Social protection as a key tool in crisis management: Learnt lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Social Welfare. 2021; 8(1):107-16.

Type of Study: Orginal Article |

Subject:

● Health Systems

Received: 2024/04/17 | Accepted: 2024/07/13 | Published: 2025/05/30

Received: 2024/04/17 | Accepted: 2024/07/13 | Published: 2025/05/30

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |