Volume 15, Issue 5 (Sep & Oct 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(5): 527-532 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: ethics code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1400.087)

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Saadatmand R, Dastjerdi G, Davari M H, Vakili M, Mehrparvar A H. Association Between Occupational Noise Exposure and Depression. J Research Health 2025; 15 (5) :527-532

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2612-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2612-en.html

Reza Saadatmand1

, Ghasem Dastjerdi2

, Ghasem Dastjerdi2

, Mohammad Hossein Davari3

, Mohammad Hossein Davari3

, Mahmood Vakili4

, Mahmood Vakili4

, Amir Houshang Mehrparvar5

, Amir Houshang Mehrparvar5

, Ghasem Dastjerdi2

, Ghasem Dastjerdi2

, Mohammad Hossein Davari3

, Mohammad Hossein Davari3

, Mahmood Vakili4

, Mahmood Vakili4

, Amir Houshang Mehrparvar5

, Amir Houshang Mehrparvar5

1- Department of Occupational Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,drmhdavari@gmail.com

4- Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Medicine, Industrial Diseases Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,

4- Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Medicine, Industrial Diseases Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 487 kb]

(236 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1705 Views)

Full-Text: (171 Views)

Introduction

Noise, as an environmental and occupational exposure, is a factor that can significantly affect humans’ physiologic balance through mechanisms such as free oxygen radical production and can impact both physical and mental health [1]. It is defined as the most frequent physical hazard in many industries, and millions of workers are exposed to noise levels higher than the permissible exposure limit (PEL) [2]. Environmental exposure to noise, such as exposure to traffic noise, has been noted as a source of hearing loss [3].

Several studies have been conducted on the effects of noise on human physical and mental health, and almost all have shown a positive relationship between exposure to noise and some disorders [1, 4]. Exposure to loud noise may deleteriously affect hearing, the cardiovascular system, mental health, and performance [5].

The most frequent health effect of noise is on the hearing system, which can lead to noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) [5]. NIHL is probably associated with other problems, such as hypertension, certain mental disorders, and decreased quality of life. Lie et al. found a higher frequency of mental disorders and lower job performance in noise-exposed workers [6]. Zeydabadi et al. showed that noise exposure affects some human cognitive functions, such as attention and memory [7]. Another study showed that workers suffering from NIHL have lower performance in some cognitive domains [8].

Presbycusis and NIHL affect quality of life and may lead to disturbance in social behaviour, making patients prone to depression and anxiety [2]. The relationship between hearing loss and depression is somehow complex, and several factors, such as social separation, communication problems, and physiologic changes, may play a role. Some studies have shown an independent relationship between hearing loss and depression [5, 9, 10]. Deng et al. found a positive relationship between NIHL and depression [2]. A cohort study with 12 years’ follow-up found a positive relationship between hearing loss and depression, independent of age, gender, and background diseases [11]. Additionally, some studies indicate that using hearing aids, which improve communication, may decrease the frequency of depression [12].

Due to the importance and high frequency of NIHL and depression, this study was performed to compare the frequency of depression among three groups of workers, considering their exposure to noise and suffering from NIHL.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 409 workers of Bafgh iron ore mine, Yazd, Iran. Workers with at least one year of work experience were included in the study. The study was performed from March 2022 to March 2023.

The workers with a history of any kind of hearing loss except for NIHL, such as conductive and mixed hearing loss, presbycusis, and unilateral hearing loss, were excluded. Also, any kind of mental disorder except for depression, such as anxiety, psychotic disorders, and bipolar mood disorders, was excluded from the study. NIHL was defined as a sensory-neural hearing loss characterized by one of the following patterns: 1) Mean hearing threshold at 3000, 4000, and 6000 Hz higher than 15 dB in each ear; or 2. An audiometric notch (a difference of more than 10 dB between the frequency with the notch and the previous and subsequent frequencies ) at one of the following frequencies: 3000, 4000, or 6000 Hz [13].

Participants were randomly selected from the workers referred for annual occupational health screening examinations using simple random sampling with a random digits table.

Initially, a questionnaire consisting of demographic information, exposure to noise, and past medical history was completed for each participant. The information about the exact exposure to noise was extracted from the environmental noise monitoring results of the plant, and the equivalent continuous sound level for 8 hours was recorded for each participant. Pure tone audiometry (PTA) was done by an expert audiologist in an acoustic chamber that met the ANSI guideline [14]. A diagnostic audiometer (Madsen AC40, Denmark) was used to record hearing thresholds at the following frequencies: 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz. A TDH-39 headphone and an oscillator were used for recording air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC) thresholds, respectively. BC testing was conducted to rule out conductive hearing loss. The audiometric tests were carried out after at least 16 hours of abstinence from exposure to noise.

The participants were divided into three groups according to exposure to noise and suffering from NIHL: 1) Control group (n=168): Without present or previous exposure to noise and with normal audiometry; 2) Noise group (n=169): With previous or present exposure to noise (higher than 85dBA) without NIHL; and 3) NIHL group (n=72): With exposure to noise (higher than 85 dBA) and with NIHL. Data about previous exposure to noise were extracted from occupational health files.

Then, the Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II) was administered to each participant. This questionnaire consists of 21 questions and is used to evaluate the severity of depression [15]. According to the BDI-II score, the participants in each group were categorized into the following categories: Normal (0-10), mild mood disturbance (11-16), borderline clinical depression (17-20), moderate depression (21-30), severe depression (31-40), and extreme depression (>40).

Data were analysed by SPSS software, version 24. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov, chi-square, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for data analysis. Confounding factors, such as other mental disorders and other types of hearing loss were considered as exclusion criteria.

Results

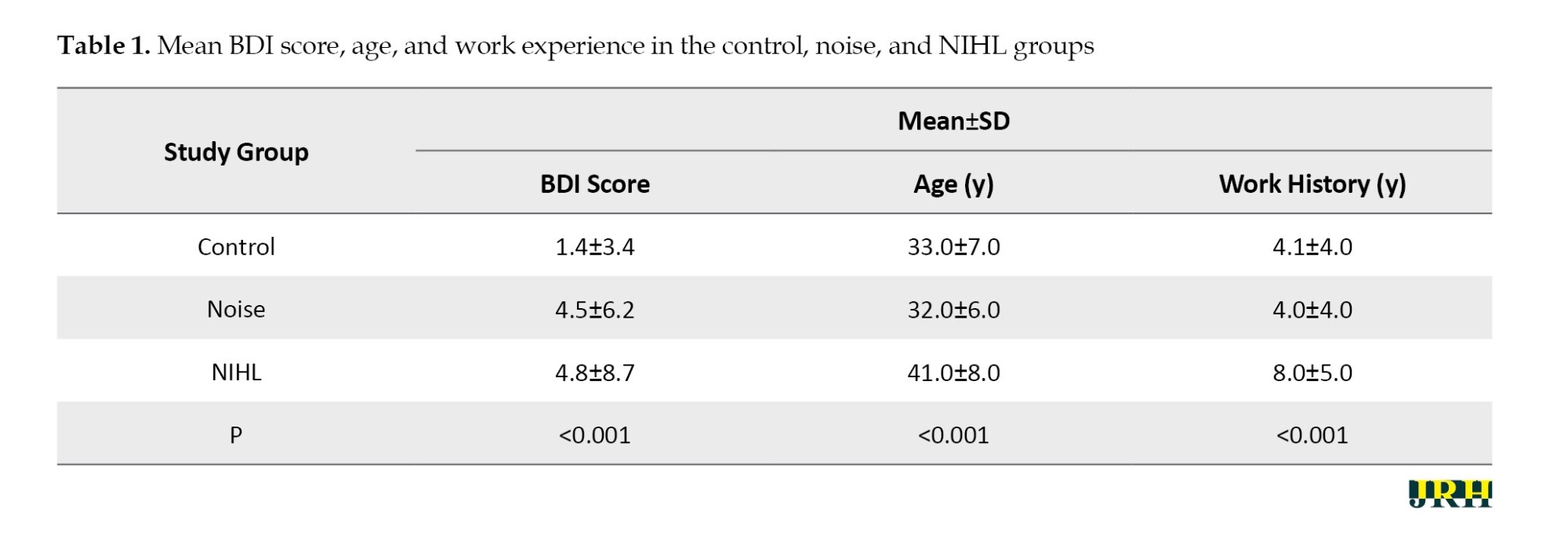

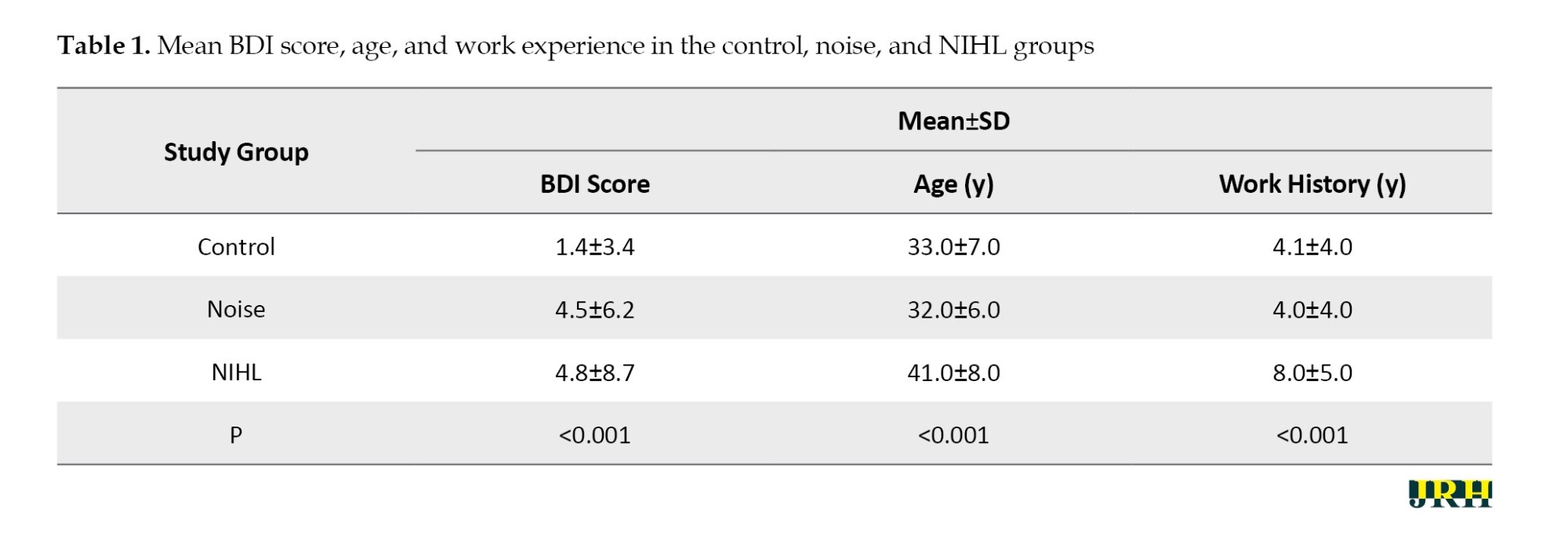

Totally, 409 workers of an iron ore mine with different jobs entered the study. Their Mean±SD age and work experience were 34.43±7.86 years (range: 20-63 years) and 5.09±4.97 years (range: 1-23 years), respectively. The mean BDI score was significantly lower in the control group compared to the other groups. Table 1 compares the mean scores of BDI, age, and work history among the three groups. Mean age and work history were significantly higher in the NIHL group.

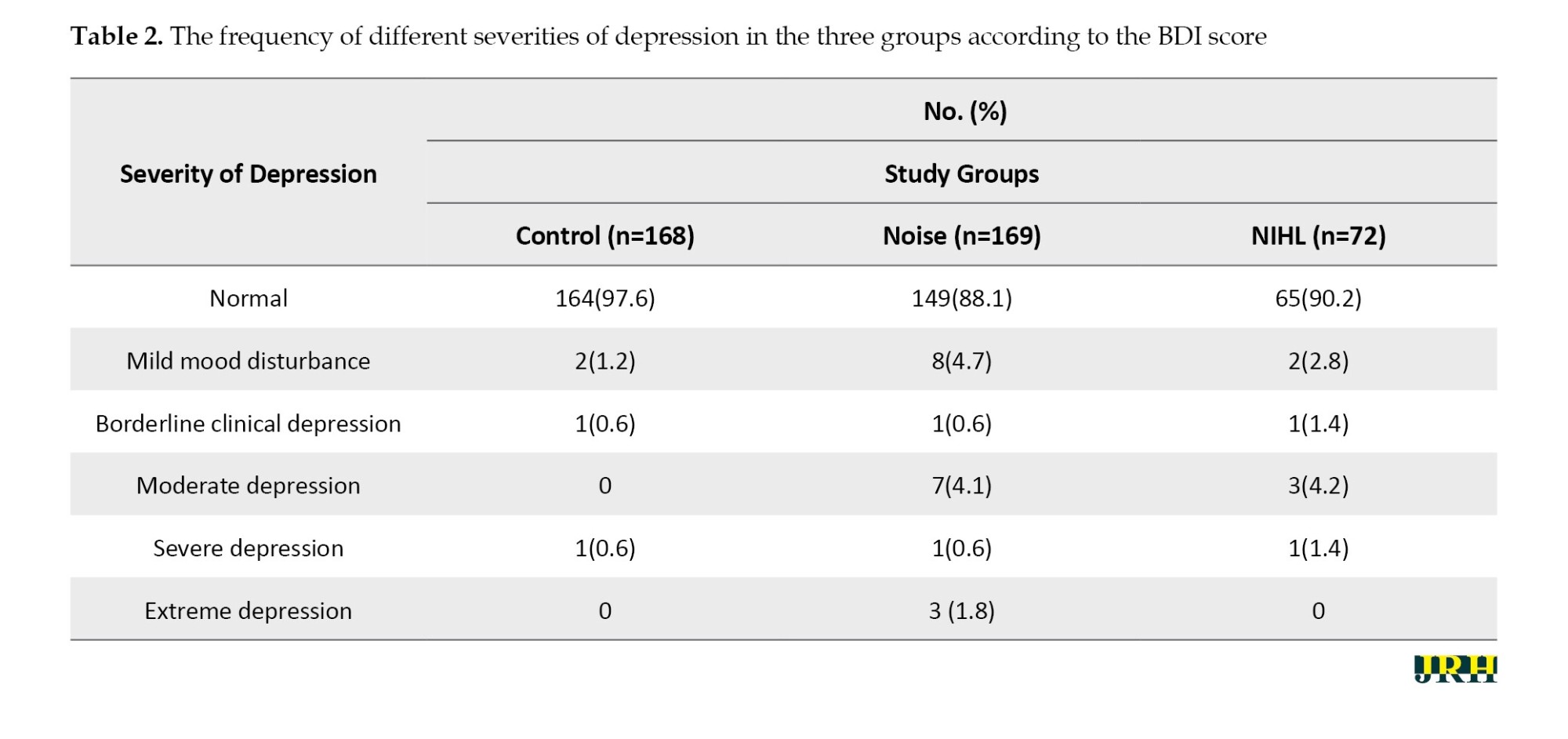

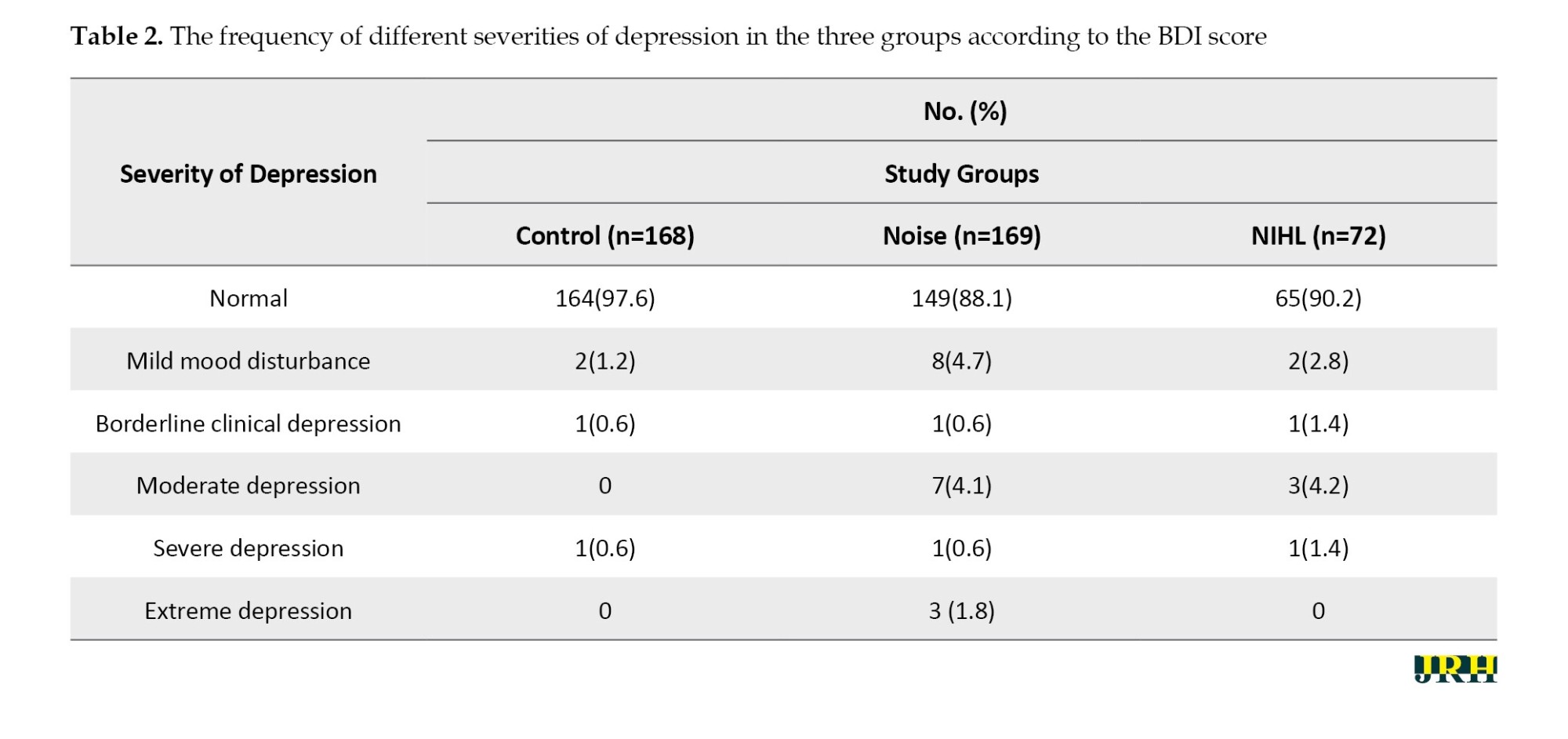

Most participants in all three groups were normal according to the BDI-II score. The frequency of depression was 2.4%, 11.7%, and 9.6% in the control, noise, and NIHL groups, respectively, and the frequency of depression was significantly different between the control and noise groups (OR=4.97, 95% CI; 1.74%, 14.23%, P=0.001), and between the control and NIHL groups (OR=4.41, 95% CI; 1.25% ,15.59%, P=0.02). However, there was no difference in the frequency of depression between the noise and NIHL groups (OR=0.81, 95% CI; 0.32%, 1.99%, P=0.82). Table 2 shows the frequency of different severities of depression in the three study groups (control, noise, and NIHL).

Discussion

The present study compared the frequency of different severities of depression among the three groups of workers (control, noise, and NIHL groups) and found a significantly higher BDI score in those exposed to noise, regardless of suffering from NIHL or not, compared to workers without exposure to noise. The frequency of depression was significantly higher in those exposed to noise compared to the control group.

NIHL is one of the most frequent occupational disorders, and there is no known treatment for it. It is an irreversible sensory-neural defect, which is caused due to the damage to sensory hair cells in the cochlea. Occupational, environmental (traffic noise, airport noise, etc.), and recreational (using portable music players, hands-free, etc.) noise exposure can cause NIHL.

A systematic review in Iran found a wide range of prevalence for NIHL (12.9% to 60.5%) in different studies [16], indicating a high prevalence for this condition. Another systematic review in China found a prevalence of 30.2% for NIHL among Chinese workers [17]. Studies have shown that NIHL and some of its complications, such as communication problems, stress, and social separation, are probably associated with some mental disorders, especially depression and anxiety [18].

Auditory perception requires both peripheral auditory perception and central auditory processing. Therefore, impairment in auditory processing and speech recognition may affect auditory performance. Previous studies have shown impaired cognitive function in those suffering from hearing loss [19]. A study on textile workers showed that workers suffering from NIHL had a lower working memory than workers without NIHL [8]. Multiple cognitive functions, including executive function, verbal memory, and attention, are impaired in depressed patients [20]. In addition, reduced activity, lack of motivation, worry, and inability to plan can reduce auditory input and central auditory pathway processing [19]. In contrast, untreated hearing loss leads to impairments in communication and social relationships, which have been reported to be associated with cognitive impairment and depression [21].

In terms of neurological function, hearing loss reduces the activity of central auditory systems, which in turn increases cognitive load and disrupts emotional relationships [22]. This perception can be applied to the present study and can be considered a reason for the higher prevalence of mood disorders in the population of employees exposed to noise.

We found a strong association between exposure to noise and suffering from depression, although the wide confidence interval decreases the accuracy of the results. The difference in age between the groups may have also affected the results of the current study. Hsu et al. found an odds ratio of 1.74 for depression in patients suffering from hearing loss [11], which is consistent with the results of the current study; however, we found a positive odds ratio for those exposed to noise, regardless of whether they developed NIHL. Thus, the mechanisms described in some studies regarding the association between hearing loss and depression, such as feelings of frustration and communication problems [23], cannot be applied in this study. Another mechanism proposed is the relationship of certain neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin and sertraline) with both depression and hearing loss [24].

Some studies have assessed the effect of environmental or occupational noise exposure on mental health. Beutel et al. in a large population-based study in Germany, found an association between strong noise annoyance (especially aircraft noise) and depression and anxiety in the general population [25]. Yoon et al. in a large study in Korea, found a strong association between occupational noise annoyance and depression, similar to the results of the current study [26]. The association between exposure to noise and its related annoyance with mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, may be due to the stress induced by the exposure to noise and its associated complications.

It should be noted that the findings of this study should be interpreted with consideration of its limitations. Since this study was cross-sectional, it is not possible to clarify the causal relationships between depression and exposure to noise. There were many confounders that could not be controlled in this study, such as economic status and shift work. It is recommended to conduct prospective and longitudinal studies to find a more precise relationship between noise exposure and depression.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed a higher BDI score and a higher frequency of depression (according to the BDI categorization) in the workers exposed to noise and those suffering from NIHL compared to the control group without exposure to high noise.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1400.087).

Funding

The study was the extracted from doctoral thesis of Reza Saadatmand, approved by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences and financially supported by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Mahmood Vakili; Data collection: Reza Saadatmand and Mohammad Hossein Davari; Revising the manuscript and data interpretation: Mahmood Vakili and Amir Houshang Mehrparvar; Conceptualization, preparing the manuscript and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Frakhondeh Sadat Hosseini and Nazanin Ghorbanizadeh Bafghi for their kind collaboration in this project.

References

Noise, as an environmental and occupational exposure, is a factor that can significantly affect humans’ physiologic balance through mechanisms such as free oxygen radical production and can impact both physical and mental health [1]. It is defined as the most frequent physical hazard in many industries, and millions of workers are exposed to noise levels higher than the permissible exposure limit (PEL) [2]. Environmental exposure to noise, such as exposure to traffic noise, has been noted as a source of hearing loss [3].

Several studies have been conducted on the effects of noise on human physical and mental health, and almost all have shown a positive relationship between exposure to noise and some disorders [1, 4]. Exposure to loud noise may deleteriously affect hearing, the cardiovascular system, mental health, and performance [5].

The most frequent health effect of noise is on the hearing system, which can lead to noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) [5]. NIHL is probably associated with other problems, such as hypertension, certain mental disorders, and decreased quality of life. Lie et al. found a higher frequency of mental disorders and lower job performance in noise-exposed workers [6]. Zeydabadi et al. showed that noise exposure affects some human cognitive functions, such as attention and memory [7]. Another study showed that workers suffering from NIHL have lower performance in some cognitive domains [8].

Presbycusis and NIHL affect quality of life and may lead to disturbance in social behaviour, making patients prone to depression and anxiety [2]. The relationship between hearing loss and depression is somehow complex, and several factors, such as social separation, communication problems, and physiologic changes, may play a role. Some studies have shown an independent relationship between hearing loss and depression [5, 9, 10]. Deng et al. found a positive relationship between NIHL and depression [2]. A cohort study with 12 years’ follow-up found a positive relationship between hearing loss and depression, independent of age, gender, and background diseases [11]. Additionally, some studies indicate that using hearing aids, which improve communication, may decrease the frequency of depression [12].

Due to the importance and high frequency of NIHL and depression, this study was performed to compare the frequency of depression among three groups of workers, considering their exposure to noise and suffering from NIHL.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 409 workers of Bafgh iron ore mine, Yazd, Iran. Workers with at least one year of work experience were included in the study. The study was performed from March 2022 to March 2023.

The workers with a history of any kind of hearing loss except for NIHL, such as conductive and mixed hearing loss, presbycusis, and unilateral hearing loss, were excluded. Also, any kind of mental disorder except for depression, such as anxiety, psychotic disorders, and bipolar mood disorders, was excluded from the study. NIHL was defined as a sensory-neural hearing loss characterized by one of the following patterns: 1) Mean hearing threshold at 3000, 4000, and 6000 Hz higher than 15 dB in each ear; or 2. An audiometric notch (a difference of more than 10 dB between the frequency with the notch and the previous and subsequent frequencies ) at one of the following frequencies: 3000, 4000, or 6000 Hz [13].

Participants were randomly selected from the workers referred for annual occupational health screening examinations using simple random sampling with a random digits table.

Initially, a questionnaire consisting of demographic information, exposure to noise, and past medical history was completed for each participant. The information about the exact exposure to noise was extracted from the environmental noise monitoring results of the plant, and the equivalent continuous sound level for 8 hours was recorded for each participant. Pure tone audiometry (PTA) was done by an expert audiologist in an acoustic chamber that met the ANSI guideline [14]. A diagnostic audiometer (Madsen AC40, Denmark) was used to record hearing thresholds at the following frequencies: 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz. A TDH-39 headphone and an oscillator were used for recording air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC) thresholds, respectively. BC testing was conducted to rule out conductive hearing loss. The audiometric tests were carried out after at least 16 hours of abstinence from exposure to noise.

The participants were divided into three groups according to exposure to noise and suffering from NIHL: 1) Control group (n=168): Without present or previous exposure to noise and with normal audiometry; 2) Noise group (n=169): With previous or present exposure to noise (higher than 85dBA) without NIHL; and 3) NIHL group (n=72): With exposure to noise (higher than 85 dBA) and with NIHL. Data about previous exposure to noise were extracted from occupational health files.

Then, the Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II) was administered to each participant. This questionnaire consists of 21 questions and is used to evaluate the severity of depression [15]. According to the BDI-II score, the participants in each group were categorized into the following categories: Normal (0-10), mild mood disturbance (11-16), borderline clinical depression (17-20), moderate depression (21-30), severe depression (31-40), and extreme depression (>40).

Data were analysed by SPSS software, version 24. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov, chi-square, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for data analysis. Confounding factors, such as other mental disorders and other types of hearing loss were considered as exclusion criteria.

Results

Totally, 409 workers of an iron ore mine with different jobs entered the study. Their Mean±SD age and work experience were 34.43±7.86 years (range: 20-63 years) and 5.09±4.97 years (range: 1-23 years), respectively. The mean BDI score was significantly lower in the control group compared to the other groups. Table 1 compares the mean scores of BDI, age, and work history among the three groups. Mean age and work history were significantly higher in the NIHL group.

Most participants in all three groups were normal according to the BDI-II score. The frequency of depression was 2.4%, 11.7%, and 9.6% in the control, noise, and NIHL groups, respectively, and the frequency of depression was significantly different between the control and noise groups (OR=4.97, 95% CI; 1.74%, 14.23%, P=0.001), and between the control and NIHL groups (OR=4.41, 95% CI; 1.25% ,15.59%, P=0.02). However, there was no difference in the frequency of depression between the noise and NIHL groups (OR=0.81, 95% CI; 0.32%, 1.99%, P=0.82). Table 2 shows the frequency of different severities of depression in the three study groups (control, noise, and NIHL).

Discussion

The present study compared the frequency of different severities of depression among the three groups of workers (control, noise, and NIHL groups) and found a significantly higher BDI score in those exposed to noise, regardless of suffering from NIHL or not, compared to workers without exposure to noise. The frequency of depression was significantly higher in those exposed to noise compared to the control group.

NIHL is one of the most frequent occupational disorders, and there is no known treatment for it. It is an irreversible sensory-neural defect, which is caused due to the damage to sensory hair cells in the cochlea. Occupational, environmental (traffic noise, airport noise, etc.), and recreational (using portable music players, hands-free, etc.) noise exposure can cause NIHL.

A systematic review in Iran found a wide range of prevalence for NIHL (12.9% to 60.5%) in different studies [16], indicating a high prevalence for this condition. Another systematic review in China found a prevalence of 30.2% for NIHL among Chinese workers [17]. Studies have shown that NIHL and some of its complications, such as communication problems, stress, and social separation, are probably associated with some mental disorders, especially depression and anxiety [18].

Auditory perception requires both peripheral auditory perception and central auditory processing. Therefore, impairment in auditory processing and speech recognition may affect auditory performance. Previous studies have shown impaired cognitive function in those suffering from hearing loss [19]. A study on textile workers showed that workers suffering from NIHL had a lower working memory than workers without NIHL [8]. Multiple cognitive functions, including executive function, verbal memory, and attention, are impaired in depressed patients [20]. In addition, reduced activity, lack of motivation, worry, and inability to plan can reduce auditory input and central auditory pathway processing [19]. In contrast, untreated hearing loss leads to impairments in communication and social relationships, which have been reported to be associated with cognitive impairment and depression [21].

In terms of neurological function, hearing loss reduces the activity of central auditory systems, which in turn increases cognitive load and disrupts emotional relationships [22]. This perception can be applied to the present study and can be considered a reason for the higher prevalence of mood disorders in the population of employees exposed to noise.

We found a strong association between exposure to noise and suffering from depression, although the wide confidence interval decreases the accuracy of the results. The difference in age between the groups may have also affected the results of the current study. Hsu et al. found an odds ratio of 1.74 for depression in patients suffering from hearing loss [11], which is consistent with the results of the current study; however, we found a positive odds ratio for those exposed to noise, regardless of whether they developed NIHL. Thus, the mechanisms described in some studies regarding the association between hearing loss and depression, such as feelings of frustration and communication problems [23], cannot be applied in this study. Another mechanism proposed is the relationship of certain neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin and sertraline) with both depression and hearing loss [24].

Some studies have assessed the effect of environmental or occupational noise exposure on mental health. Beutel et al. in a large population-based study in Germany, found an association between strong noise annoyance (especially aircraft noise) and depression and anxiety in the general population [25]. Yoon et al. in a large study in Korea, found a strong association between occupational noise annoyance and depression, similar to the results of the current study [26]. The association between exposure to noise and its related annoyance with mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, may be due to the stress induced by the exposure to noise and its associated complications.

It should be noted that the findings of this study should be interpreted with consideration of its limitations. Since this study was cross-sectional, it is not possible to clarify the causal relationships between depression and exposure to noise. There were many confounders that could not be controlled in this study, such as economic status and shift work. It is recommended to conduct prospective and longitudinal studies to find a more precise relationship between noise exposure and depression.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed a higher BDI score and a higher frequency of depression (according to the BDI categorization) in the workers exposed to noise and those suffering from NIHL compared to the control group without exposure to high noise.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1400.087).

Funding

The study was the extracted from doctoral thesis of Reza Saadatmand, approved by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences and financially supported by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Mahmood Vakili; Data collection: Reza Saadatmand and Mohammad Hossein Davari; Revising the manuscript and data interpretation: Mahmood Vakili and Amir Houshang Mehrparvar; Conceptualization, preparing the manuscript and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Frakhondeh Sadat Hosseini and Nazanin Ghorbanizadeh Bafghi for their kind collaboration in this project.

References

- Chen KH, Su SB, Chen KT. An overview of occupational noise-induced hearing loss among workers: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and preventive measures. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 2020; 25(1):65. [DOI:10.1186/s12199-020-00906-0] [PMID]

- Deng XF, Shi GQ, Guo LL, Zhu CA, Chen YJ. Analysis on risk factors of depressive symptoms in occupational noise-induced hearing loss patients: A cross-sectional study. Noise & Health. 2019; 21(98):17-24. [DOI:10.4103/nah.NAH_16_18] [PMID]

- Neshati A, Davari MH, Mollasadeghi A, Vakili M, Mehrparvar AH. [Effect of exposure to recreational noise on hearing threshold levels in medical students (Persian)]. Occupational Medicine. 2024; 16(2):34-42. [DOI:10.18502/tkj.v16i2.16089]

- Abbasi M, Pourrajab B, Tokhi MO. Protective effects of vitamins/antioxidants on occupational noise-induced hearing loss: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health. 2021; 63(1):e12217. [DOI:10.1002/1348-9585.12217] [PMID]

- Nadri H, Khavanin A, Kim I-J, Akbari M, Nadri F. Association between simultaneous occurrence of occupational noise-induced hearing loss and noise-induced vestibular dysfunction: A systematic review. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2023; 52(4):683-94. [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v52i4.12436] [PMID]

- Lie A, Engdahl B, Hoffman HJ, Li CM, Tambs K. Occupational noise exposure, hearing loss, and notched audiograms in the HUNT Nord-Trøndelag hearing loss study, 1996-1998. The Laryngoscope. 2017; 127(6):1442-50. [DOI:10.1002/lary.26256] [PMID]

- Zeydabadi A, Askari J, Vakili M, Mirmohammadi SJ, Ghovveh MA, Mehrparvar AH. The effect of industrial noise exposure on attention, reaction time, and memory. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2019; 92(1):111-6. [DOI:10.1007/s00420-018-1361-0] [PMID]

- Rahimian B, Jambarsang S, Mehrparvar AH. The relationship between noise-induced hearing loss and cognitive function. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health. 2023; 78(5):283-8. [DOI:10.1080/19338244.2023.2174927] [PMID]

- Shi Z, Zhou J, Huang Y, Hu Y, Zhou L, Shao Y, et al. Occupational hearing loss associated with non-Gaussian noise: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ear and Hearing. 2021; 42(6):1472-84. [DOI:10.1097/AUD.0000000000001060] [PMID]

- Si S, Lewkowski K, Fritschi L, Heyworth J, Liew D, Li I. Productivity burden of occupational noise-induced hearing loss in Australia: a life table modelling study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(13):4667. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17134667] [PMID]

- Hsu WT, Hsu CC, Wen MH, Lin HC, Tsai HT, Su P, et al. Increased risk of depression in patients with acquired sensory hearing loss: A 12-year follow-up study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(44):e5312. [PMID]

- Mener DJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, Chen D, Lin FR. Hearing loss and depression in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013; 61(9):1627-9. [DOI:10.1111/jgs.12429] [PMID]

- Mehrparvar AH, Farzan A, Sakhvidi MJ, Davari MH. The efficacy of extended high-frequency audiometry in early detection of noise-induced hearing loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Occupational Hygiene. 2018. 24; 10(4):250-64. [Link]

- American National Standard. Specification for audiometers: Acoustical Society of America. New York: American National Standard; 2010. [Link]

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depression and Anxiety. 2005; 21(4):185-92. [DOI:10.1002/da.20070] [PMID]

- Etemadinezhad S, Sammak Amani A, Moosazadeh M, Rahimlou M, Samaei SE. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2023; 52(2):278-89. [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v52i2.11881] [PMID]

- Zhou J, Shi Z, Zhou L, Hu Y, Zhang M. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(9):e039576. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039576] [PMID]

- Chi I, Yip PS, Chiu HF, Chou KL, Chan KS, Kwan CW, et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlates in Hong Kong’s Chinese older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005; 13(5):409-16. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.409] [PMID]

- Thomas P, Hazif Thomas C, Billon R, Peix R, Faugeron P, Clément JP. [Depression and frontal dysfunction: risks for the elderly? (French)]. L'Encephale. 2009; 35(4):361-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.encep.2008.03.012] [PMID]

- Bortolato B, Miskowiak KW, Köhler CA, Maes M, Fernandes BS, Berk M, et al. Cognitive remission: A novel objective for the treatment of major depression? BMC Medicine. 2016; 14:9. [DOI:10.1186/s12916-016-0560-3] [PMID]

- Dawes P, Emsley R, Cruickshanks KJ, Moore DR, Fortnum H, Edmondson-Jones M, et al. Hearing loss and cognition: The role of hearing AIDS, social isolation and depression. PLoS One. 2015; 10(3):e0119616. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0119616] [PMID]

- Rutherford BR, Brewster K, Golub JS, Kim AH, Roose SP. Sensation and psychiatry: Linking age-related hearing loss to late-life depression and cognitive decline. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2018; 175(3):215-24. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040423] [PMID]

- Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Negative consequences of hearing impairment in old age: A longitudinal analysis. The Gerontologist. 2000; 40(3):320-6. [DOI:10.1093/geront/40.3.320] [PMID]

- Helton SG, Lohoff FW. Serotonin pathway polymorphisms and the treatment of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Pharmacogenomics. 2015; 16(5):541-53. [DOI:10.2217/pgs.15.15] [PMID]

- Beutel ME, Jünger C, Klein EM, Wild P, Lackner K, Blettner M, et al. Noise annoyance is associated with depression and anxiety in the general population-the contribution of aircraft noise. Plos One. 2016; 11(5):e0155357. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0155357] [PMID]

- Yoon JH, Won JU, Lee W, Jung PK, Roh J. Occupational noise annoyance linked to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation: A result from nationwide survey of Korea. Plos One. 2014; 9(8):e105321. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0105321] [PMID]

Type of Study: Short Communication |

Subject:

● Disease Control

Received: 2024/08/23 | Accepted: 2024/12/16 | Published: 2025/08/5

Received: 2024/08/23 | Accepted: 2024/12/16 | Published: 2025/08/5

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |