Volume 15, Issue 4 (Jul & Aug 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(4): 411-420 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: nil

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Chukwu O O, Umoke M, Iyare C. Anxiety and Depression Among Health Science Undergraduates in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. J Research Health 2025; 15 (4) :411-420

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2688-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2688-en.html

1- Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medical Sciences, David Umahi Federal University of Health Sciences, Uburu, Nigeria. , chukwuoo46@gmail.com

2- Department of Physical and Health Education, Faculty of Education, Alex Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Achoro-Ndiagu, Nigeria.

3- Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medical Sciences, David Umahi Federal University of Health Sciences, Uburu, Nigeria.

2- Department of Physical and Health Education, Faculty of Education, Alex Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Achoro-Ndiagu, Nigeria.

3- Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medical Sciences, David Umahi Federal University of Health Sciences, Uburu, Nigeria.

Full-Text [PDF 623 kb]

(442 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2749 Views)

Full-Text: (324 Views)

Introduction

Health science programs are known for their rigorous academic demands, placing students in highly stressful environments that can significantly impact their mental health. Aspiring healthcare professionals must meet high academic standards, pass difficult exams, acquire practical clinical skills, and perform under pressure [1]. Emotional strain from clinical placements and internships further exacerbates these pressures [2], creating a breeding ground for anxiety and depression, which can affect both academic performance and long-term well-being [3]. While the mental health of tertiary institutions students has been widely studied, health science students, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Nigeria, have received less attention. Studies globally have documented high rates of stress, anxiety and depression among medical students, with academic pressure, clinical exposure, and limited mental health resources being major contributors [4, 5]. Furthermore, mental health issues among students in health science programs are linked to poor academic performance and increased absenteeism [6]. However, research on the specific challenges faced by health science students in Nigeria remains sparse.

This study addresses this gap by examining mental health in health science undergraduates in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. It explores the role of cultural norms, gender roles, and age-related factors, as these elements may influence the expression and reporting of anxiety and depression. For instance, cultural attitudes towards mental health in Ebonyi State may impact how symptoms are expressed and addressed. Understanding these factors is critical to developing culturally appropriate mental health interventions for this group. This study also seeks to provide practical recommendations for improving mental health services and academic support systems at universities to better equip future healthcare professionals in Nigeria.

Methods

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to assess the mental health of health science undergraduates in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The study design enabled a snapshot of anxiety and depression symptoms in this population at a single point in time, using validated measurement tools. The research was conducted from September to November 2023.

Study population

The study focused on health science undergraduates enrolled in tertiary institutions in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The population was selected due to the unique academic pressures and challenges health science students face. Participants were drawn from various disciplines, including medicine, nursing, pharmacy, radiography, medical laboratory science, and public health. The study aimed to recruit students of diverse age ranges, primarily those between 18 and 29 years old, with some older students included.

Sampling technique

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed. First, tertiary institutions offering health science programs in Ebonyi State were identified. Proportional sampling was then used to select participants from each institution based on student enrollment numbers. Within each institution, convenience sampling was used to recruit students who were willing to participate.

Sample size calculation

A power analysis was conducted using G*Power software, version 3.1 to determine the required sample size. The analysis accounted for the anticipated prevalence of anxiety and depression in the target population, aiming for a statistical power of 80% at a significance level of 0.05. This calculation ensured sufficient power to detect moderate effect sizes related to mental health outcomes.

Measurement tools

Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAM-A)

Hamilton developed the 14-item HAM-A in 1959 [7]. The scale was used to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms. It assesses both psychic (mental) and somatic (physical) symptoms of anxiety, with participants rating each symptom from 0 (not present) to 4 (severe). The total score ranges from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. The HAM-A is a well-established tool with strong reliability and validity across various populations [1]. The scale’s internal consistency (the Cronbach α) typically ranges between 0.70 and 0.90 and the test re-test reliability is robust in clinical settings. The scale effectively discriminates between patients with anxiety disorders and those with other psychiatric conditions, contributing to its widespread use in both research and clinical environments [7].

Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Kroenke et al. developed the PHQ-9 in 1999. It is a 9-item questionnaire used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms [8]. Each item is rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) based on how often the participant experiences a symptom over the past two weeks. The total score ranges from 0 to 27 and is calculated by summing the individual item scores. The severity of depression is categorized as follows:

0–4: None or minimal depression, 5–9: Mild depression, 10–14: Moderate depression, 15–19: Moderately severe depression, 20–27: Severe depression. The PHQ-9 has been extensively validated in different populations, demonstrating strong psychometric properties and reliability [8, 9].

Survey methodology

Data were collected via an online Google Forms survey. The survey was distributed through email lists, social media groups, and online forums commonly frequented by health science students in Ebonyi State. The survey included the HAM-A, PHQ-9 and additional questions regarding demographics and items related to potential risk factors for anxiety and depression, such as academic workload, clinical exposure and personal life stressors. All questions were adapted to be appropriate for the context of health science students in Nigeria. The questionnaires used in the study were validated tools for measuring anxiety and depression symptoms in student populations.

The inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Health science undergraduates enrolled in universities in Ebonyi State, participants aged 16 years and older, and willingness to provide informed consent for participation in the study.

The exclusion criteria

Undergraduates with a pre-existing diagnosis or ongoing treatment for severe mental health conditions (e.g. major depression, severe anxiety disorders) were excluded to avoid bias in the results and to ensure the study focused on students without prior severe mental health diagnoses.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data and the chi-square test was applied to explore associations between variables, such as the severity of anxiety and depression, and demographic characteristics.

Results

Out of the 399 copies of the questionnaire administered, 383 were returned, properly filled and fitted for analysis, giving a response rate of 96.0%.

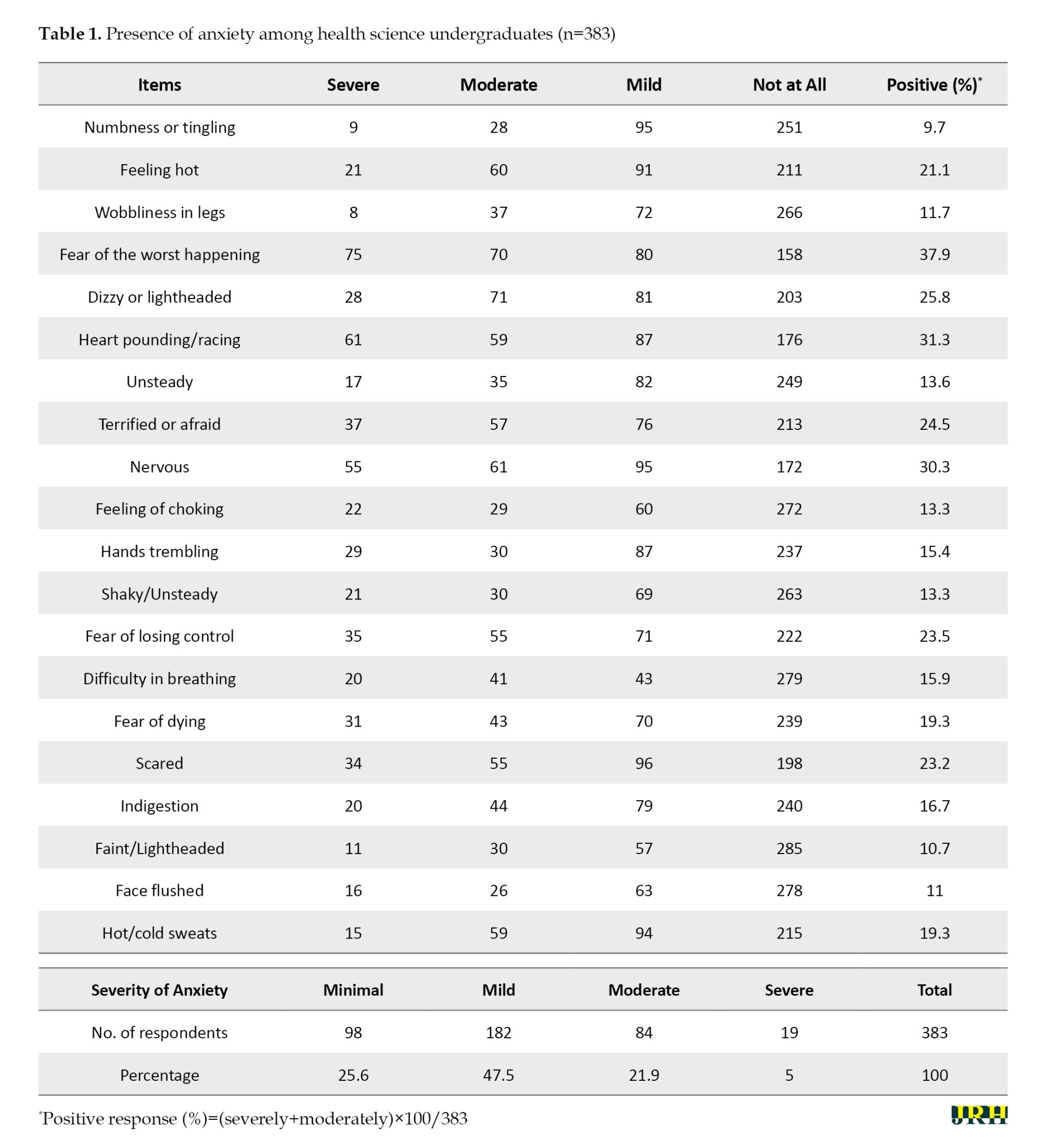

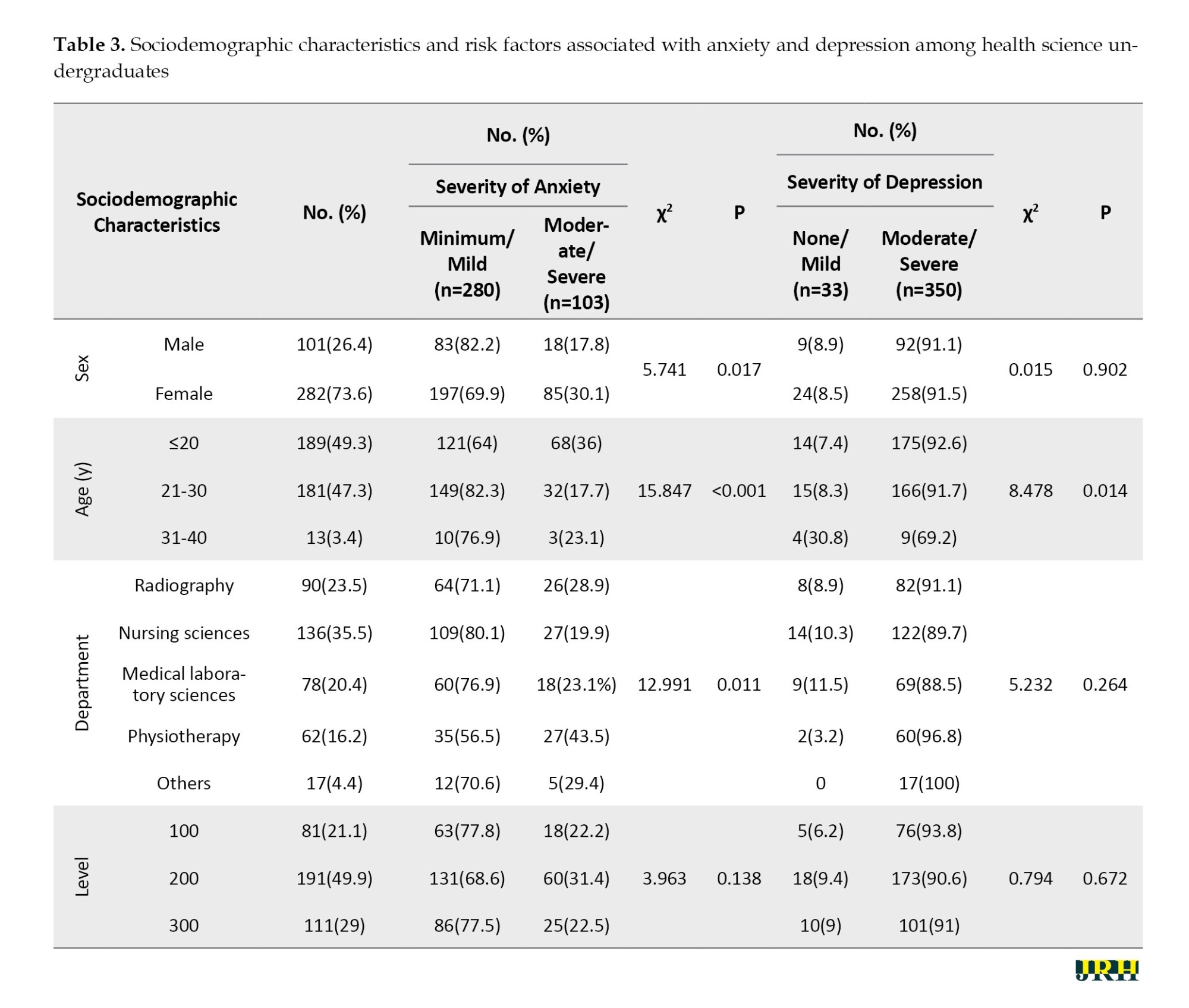

Presence of anxiety among health science undergraduates

A significant proportion of respondents experienced anxiety symptoms. The most common symptom was “fear of the worst happening” (37.9%), followed by other symptoms of anxiety (Table 1). The majority of respondents (47.5%) fell into the “mild anxiety” category. This finding indicates that while anxiety is prevalent among health science undergraduates, it is mostly mild.

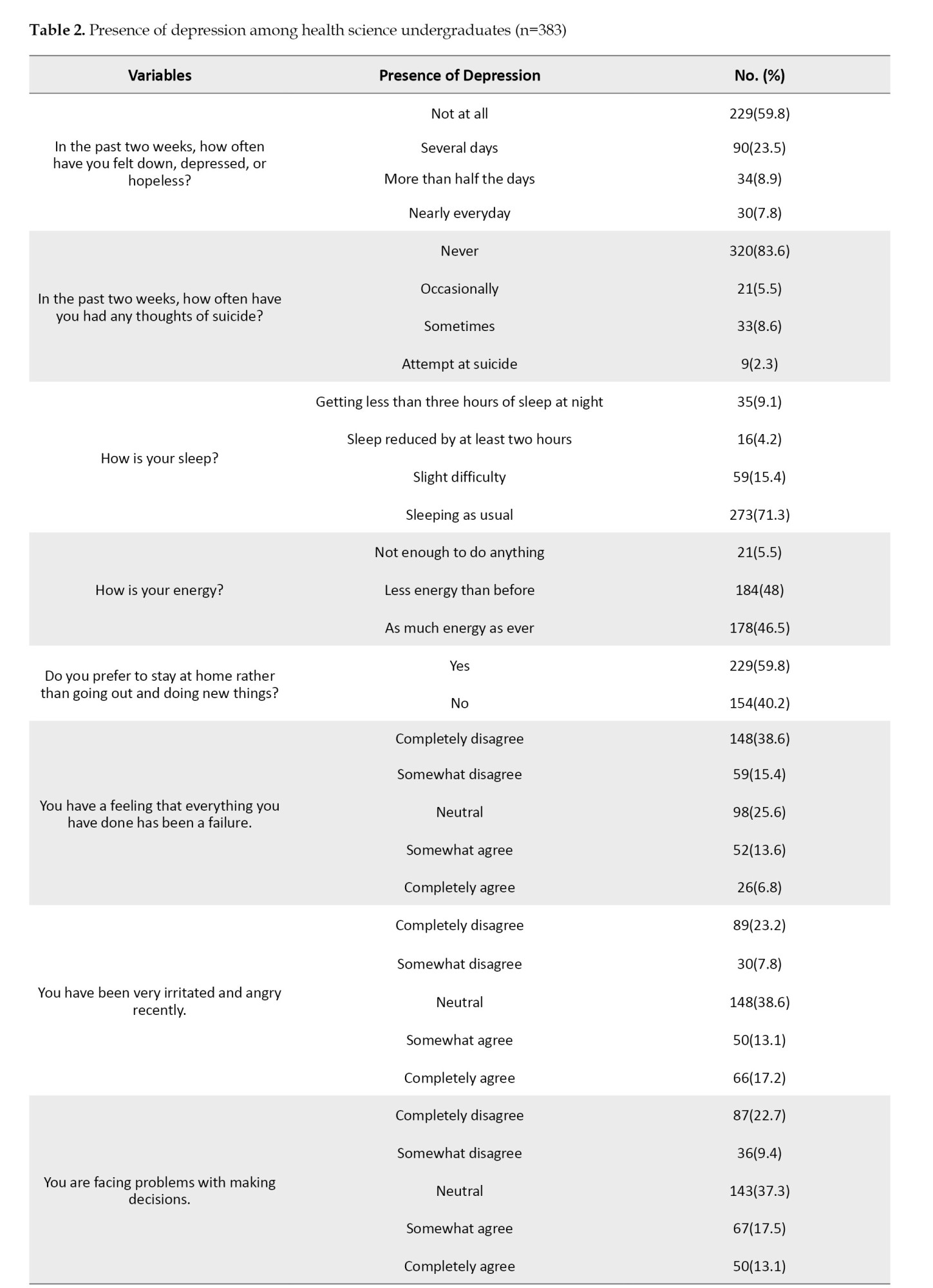

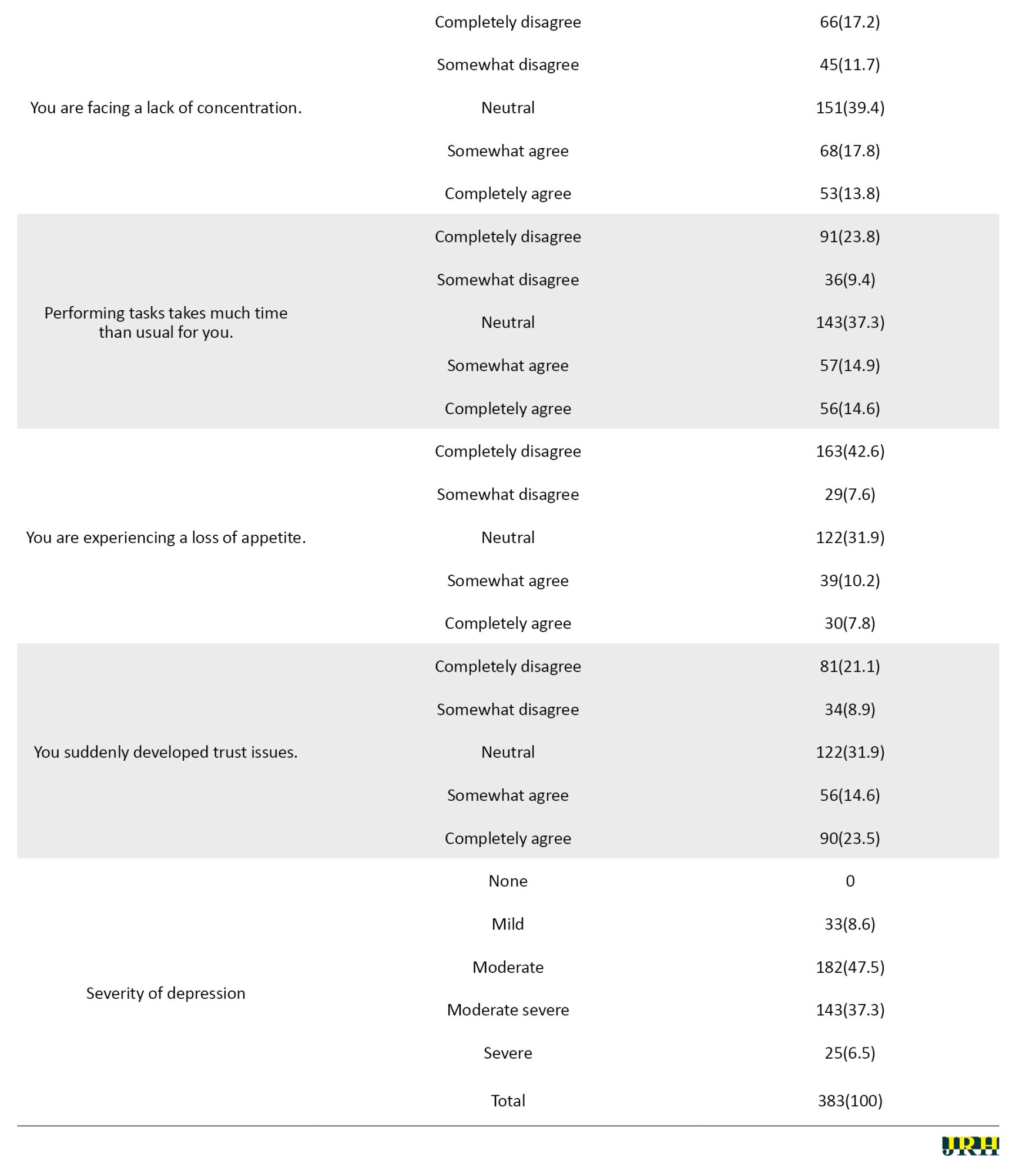

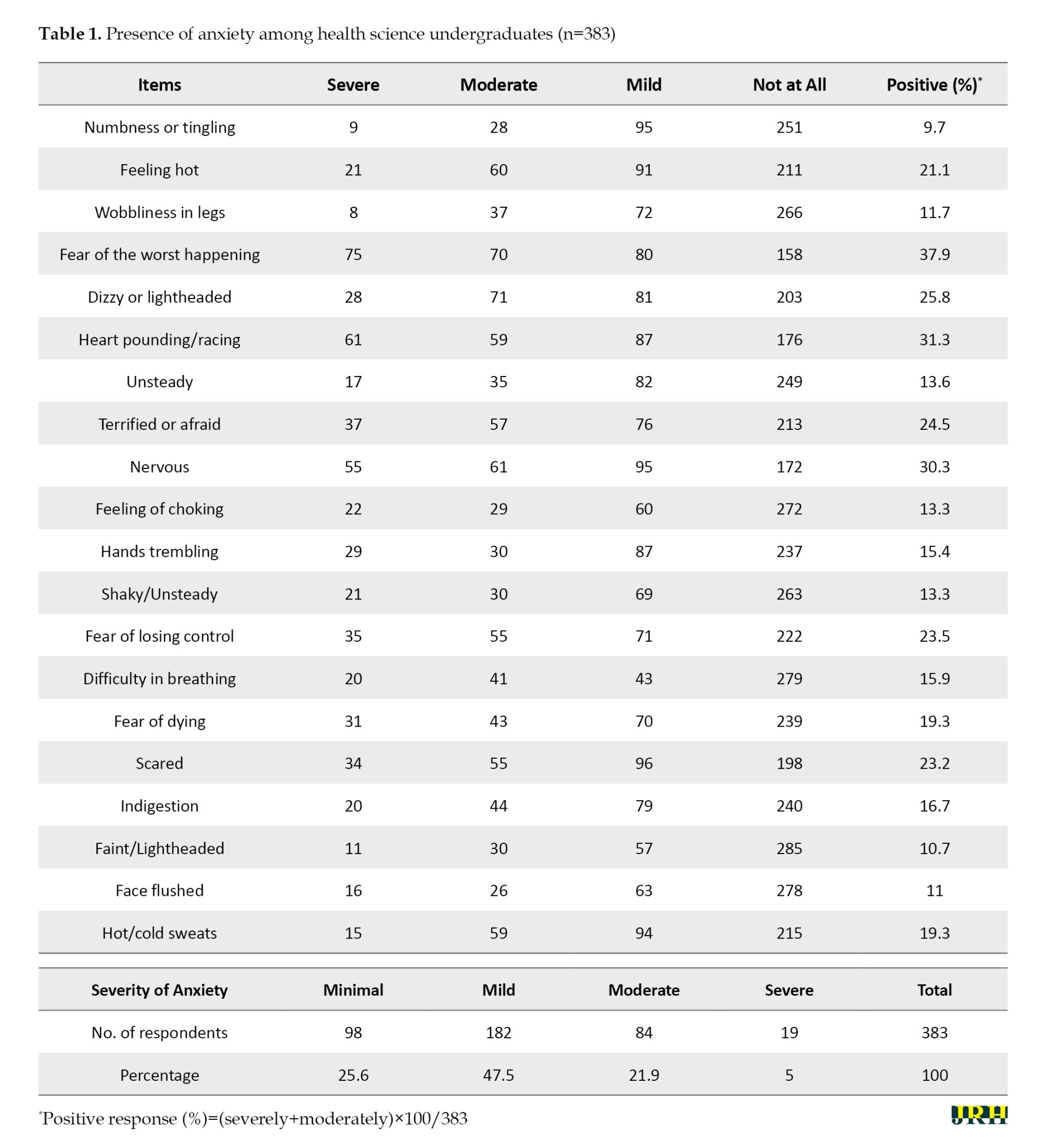

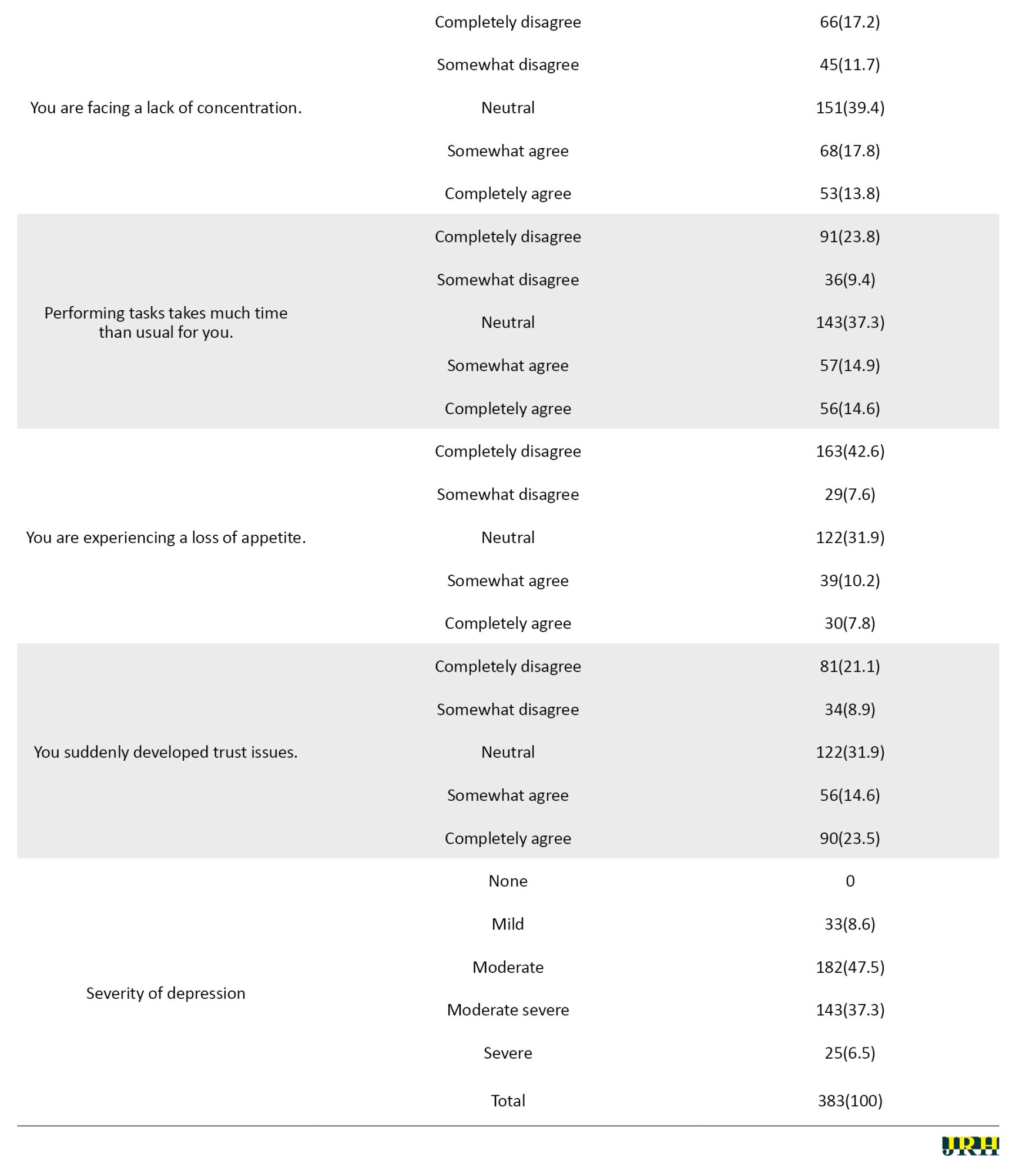

Presence of depression among health science undergraduates

A high prevalence of depressive symptoms was observed. Specifically, 8.6% of respondents reported mild depression, 47.5% experienced moderate depression, 37.3% had moderate to severe depression, and 6.5% reported severe depression (Table 2). These findings highlight the significant mental health challenges faced by health science undergraduates, with a considerable portion experiencing moderate to severe depression.

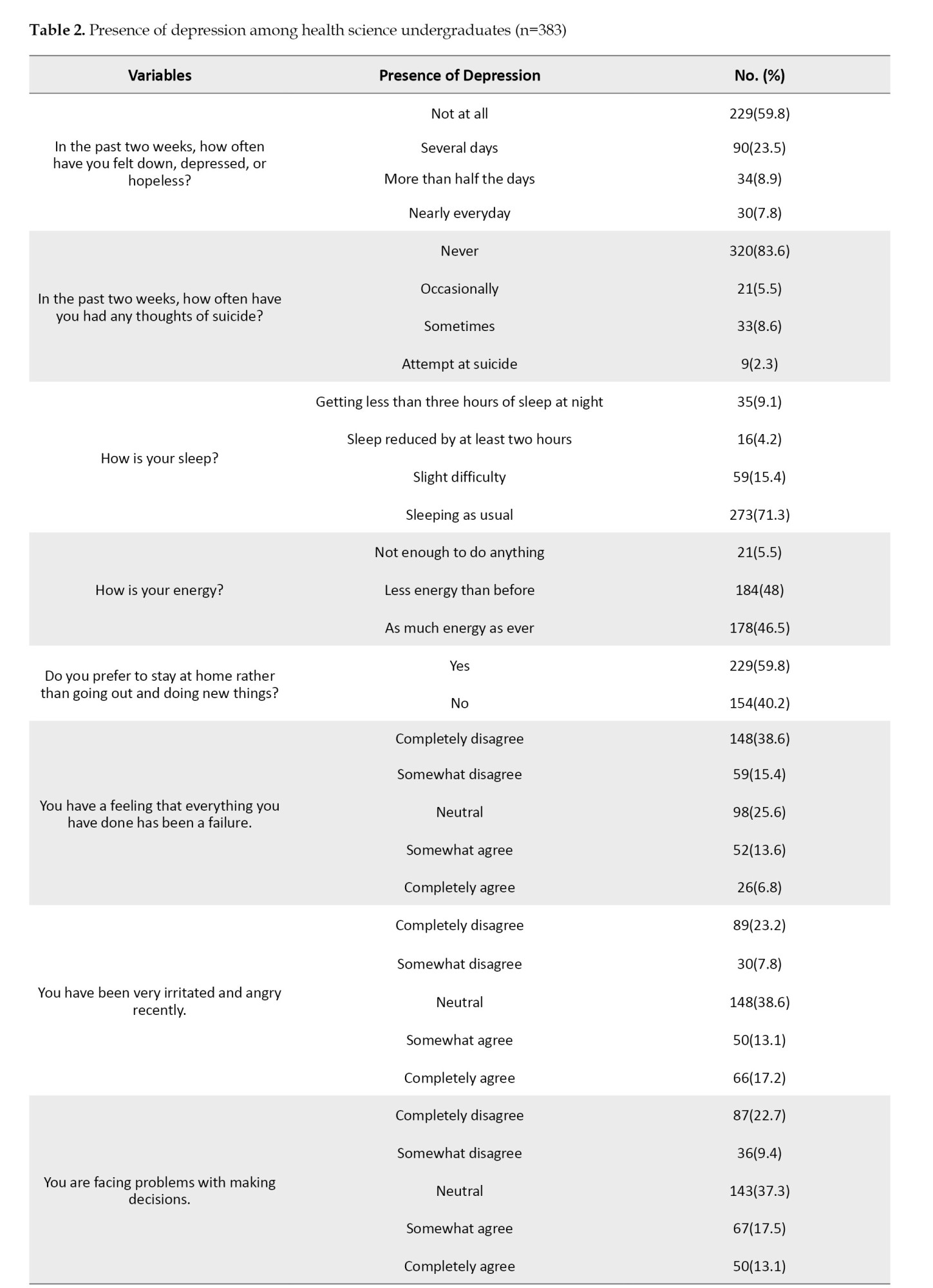

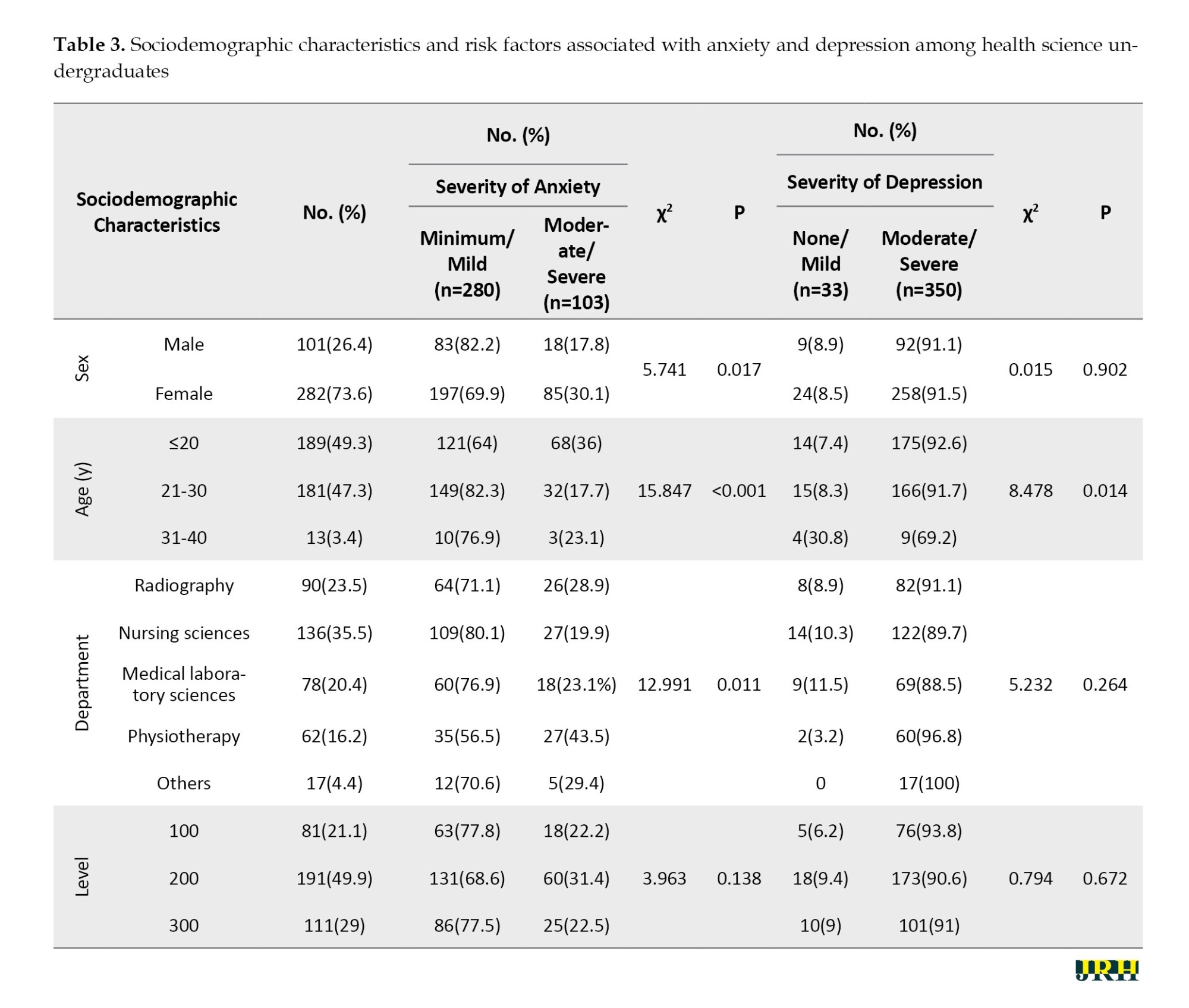

Risk factors for anxiety and depression among health science students

The sociodemographic breakdown of respondents is shown in Table 3. Most participants were female (73.6%), young (primarily ≤20 and 21-30 years old), and from the Nursing Sciences Department (35.5%). Females were more likely to experience moderate/severe anxiety compared to males (30.1% vs 17.8%), suggesting that gender influences anxiety levels. Younger participants (≤20 years old) also had higher levels of moderate/severe anxiety (36.0%) than older groups, indicating age as a key factor in anxiety severity. Radiography students showed the highest percentage of moderate/severe anxiety (28.9%) (Table 3). Older participants (31-40 years old) were significantly less likely to experience moderate or severe depression compared to the youngest group (7.4% vs 30.8%), indicating that depression severity varies with age.

No significant differences were found in depression severity across sexes, academic departments, or academic levels, suggesting that depression may not be strongly influenced by these demographic factors (Table 3).

Discussion

This study’s finding of higher moderate to severe anxiety among female students is consistent with previous research showing higher anxiety levels in females in academic settings [10, 11]. However, it highlights the importance of considering cultural influences, such as those specific to Ebonyi State. Socialization patterns may lead females to express emotional distress more readily than males, who may suppress symptoms due to cultural gender norms [12, 13]. This finding emphasizes the need for culturally sensitive anxiety assessments and challenges the limitations of universal approaches in diverse populations.

The lower depression prevalence observed in the youngest age group, compared to older students, contradicts research suggesting higher depression rates among adolescents and young adults [14, 15]. This result could be due to protective social support systems in Ebonyi State, which may buffer younger students from mental health impacts [15, 16]. This finding calls for further culturally specific investigations into depression among university students, as universal assumptions about age-related risks may not apply in all contexts.

The lack of a significant sex difference in depression prevalence contrasts with studies showing higher rates in females [17, 18]. This discrepancy could stem from cultural factors in Ebonyi State that discourage males from acknowledging distress, leading to underreporting of depressive symptoms. The sample size or limitations in measurement tools, such as the PHQ-9, may also explain the lack of observed gender differences.

Finally, the mental health challenges university students face in this study reflect broader trends in academic populations [10, 19]. Like previous research by Maeng & Milad [11] and Asher et al. [20], the study confirms that students in high-pressure fields like health sciences experience heightened anxiety and depression. These findings underscore the need for targeted mental health interventions, such as counseling and stress-management programs, to address the specific challenges faced by health science students, as supported by Hawes et al. [16].

Conclusion

This study reveals a concerning prevalence of anxiety and depression among health science students in Nigeria, highlighting the urgent need for specific mental health interventions tailored to their academic and clinical pressures. To support these students’ well-being and educational success, universities should implement counseling services, peer support programs, and stress-management workshops. These interventions should address health science students’ unique stressors, such as clinical rotations, academic workload, and exposure to high-stress environments.

Recommendations

Future research should investigate the impact of specific stressors, particularly clinical rotations and academic workload, on mental health outcomes. Additionally, exploring the role of institutional support systems, such as mentorship, peer support, and faculty engagement, could provide valuable insights into effective interventions. To address the limitations of this study, future research should consider longitudinal designs to track changes over time and use larger, more diverse samples to enhance generalizability.

Implications for policymakers

We recommend prioritizing mental health in academic institutions through the implementation of mandatory mental health screenings for all students, especially those in high-stress programs like health sciences, ensuring adequate funding and staffing for mental health counseling services on campus, and organizing awareness campaigns to reduce stigma associated with mental health issues and encourage help-seeking behavior.

We suggest integrating mental health into curricula by incorporating mental health education, emphasizing stress management, coping strategies, and self-care techniques. We also recommend implementing flexible academic policies to accommodate students’ mental health needs, such as extensions on assignments and exams.

Finally, support for vulnerable groups must be provided through the development of targeted interventions for female and younger students who are at higher risk of anxiety, fostering peer support programs to provide emotional support and reduce feelings of isolation.

Implications for the public

Reduce stigma by challenging negative stereotypes and misconceptions about mental illness.

Promote open dialogue by encouraging open conversations about mental health to normalize seeking help.

Support mental health initiatives by advocating for increased funding and resources for mental health services.

Practice self-care by prioritizing self-care practices like mindfulness, exercise, and adequate sleep.

Limitations of the study

This study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships, and longitudinal studies are needed to track changes in mental health over time. The self-report nature of the study may also introduce social desirability bias, potentially underestimating the true prevalence of mental health issues. Although the sample size of 383 participants provides a solid foundation, it may not fully represent Southeast Nigeria’s broader population of health science students. A larger sample size could enhance the generalizability of the findings and uncover additional data nuances.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the College of Health Sciences Ethical Research Committee Evangel University Akaeze, Ebonyi State, Nigeria (Code: EU/CHERC/2022).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing the original draft and project administration: Odochi Chukwu and Maryjoy Umoke; Formal analysis and resources: Odochi Chukwu; Investigation, review and editing: Odochi Chukwu and Cordilia Iyare; Supervision and validation: Maryjoy Umoke.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for contributing to the research.

References

Health science programs are known for their rigorous academic demands, placing students in highly stressful environments that can significantly impact their mental health. Aspiring healthcare professionals must meet high academic standards, pass difficult exams, acquire practical clinical skills, and perform under pressure [1]. Emotional strain from clinical placements and internships further exacerbates these pressures [2], creating a breeding ground for anxiety and depression, which can affect both academic performance and long-term well-being [3]. While the mental health of tertiary institutions students has been widely studied, health science students, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Nigeria, have received less attention. Studies globally have documented high rates of stress, anxiety and depression among medical students, with academic pressure, clinical exposure, and limited mental health resources being major contributors [4, 5]. Furthermore, mental health issues among students in health science programs are linked to poor academic performance and increased absenteeism [6]. However, research on the specific challenges faced by health science students in Nigeria remains sparse.

This study addresses this gap by examining mental health in health science undergraduates in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. It explores the role of cultural norms, gender roles, and age-related factors, as these elements may influence the expression and reporting of anxiety and depression. For instance, cultural attitudes towards mental health in Ebonyi State may impact how symptoms are expressed and addressed. Understanding these factors is critical to developing culturally appropriate mental health interventions for this group. This study also seeks to provide practical recommendations for improving mental health services and academic support systems at universities to better equip future healthcare professionals in Nigeria.

Methods

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to assess the mental health of health science undergraduates in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The study design enabled a snapshot of anxiety and depression symptoms in this population at a single point in time, using validated measurement tools. The research was conducted from September to November 2023.

Study population

The study focused on health science undergraduates enrolled in tertiary institutions in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The population was selected due to the unique academic pressures and challenges health science students face. Participants were drawn from various disciplines, including medicine, nursing, pharmacy, radiography, medical laboratory science, and public health. The study aimed to recruit students of diverse age ranges, primarily those between 18 and 29 years old, with some older students included.

Sampling technique

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed. First, tertiary institutions offering health science programs in Ebonyi State were identified. Proportional sampling was then used to select participants from each institution based on student enrollment numbers. Within each institution, convenience sampling was used to recruit students who were willing to participate.

Sample size calculation

A power analysis was conducted using G*Power software, version 3.1 to determine the required sample size. The analysis accounted for the anticipated prevalence of anxiety and depression in the target population, aiming for a statistical power of 80% at a significance level of 0.05. This calculation ensured sufficient power to detect moderate effect sizes related to mental health outcomes.

Measurement tools

Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAM-A)

Hamilton developed the 14-item HAM-A in 1959 [7]. The scale was used to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms. It assesses both psychic (mental) and somatic (physical) symptoms of anxiety, with participants rating each symptom from 0 (not present) to 4 (severe). The total score ranges from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. The HAM-A is a well-established tool with strong reliability and validity across various populations [1]. The scale’s internal consistency (the Cronbach α) typically ranges between 0.70 and 0.90 and the test re-test reliability is robust in clinical settings. The scale effectively discriminates between patients with anxiety disorders and those with other psychiatric conditions, contributing to its widespread use in both research and clinical environments [7].

Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Kroenke et al. developed the PHQ-9 in 1999. It is a 9-item questionnaire used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms [8]. Each item is rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) based on how often the participant experiences a symptom over the past two weeks. The total score ranges from 0 to 27 and is calculated by summing the individual item scores. The severity of depression is categorized as follows:

0–4: None or minimal depression, 5–9: Mild depression, 10–14: Moderate depression, 15–19: Moderately severe depression, 20–27: Severe depression. The PHQ-9 has been extensively validated in different populations, demonstrating strong psychometric properties and reliability [8, 9].

Survey methodology

Data were collected via an online Google Forms survey. The survey was distributed through email lists, social media groups, and online forums commonly frequented by health science students in Ebonyi State. The survey included the HAM-A, PHQ-9 and additional questions regarding demographics and items related to potential risk factors for anxiety and depression, such as academic workload, clinical exposure and personal life stressors. All questions were adapted to be appropriate for the context of health science students in Nigeria. The questionnaires used in the study were validated tools for measuring anxiety and depression symptoms in student populations.

The inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Health science undergraduates enrolled in universities in Ebonyi State, participants aged 16 years and older, and willingness to provide informed consent for participation in the study.

The exclusion criteria

Undergraduates with a pre-existing diagnosis or ongoing treatment for severe mental health conditions (e.g. major depression, severe anxiety disorders) were excluded to avoid bias in the results and to ensure the study focused on students without prior severe mental health diagnoses.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data and the chi-square test was applied to explore associations between variables, such as the severity of anxiety and depression, and demographic characteristics.

Results

Out of the 399 copies of the questionnaire administered, 383 were returned, properly filled and fitted for analysis, giving a response rate of 96.0%.

Presence of anxiety among health science undergraduates

A significant proportion of respondents experienced anxiety symptoms. The most common symptom was “fear of the worst happening” (37.9%), followed by other symptoms of anxiety (Table 1). The majority of respondents (47.5%) fell into the “mild anxiety” category. This finding indicates that while anxiety is prevalent among health science undergraduates, it is mostly mild.

Presence of depression among health science undergraduates

A high prevalence of depressive symptoms was observed. Specifically, 8.6% of respondents reported mild depression, 47.5% experienced moderate depression, 37.3% had moderate to severe depression, and 6.5% reported severe depression (Table 2). These findings highlight the significant mental health challenges faced by health science undergraduates, with a considerable portion experiencing moderate to severe depression.

Risk factors for anxiety and depression among health science students

The sociodemographic breakdown of respondents is shown in Table 3. Most participants were female (73.6%), young (primarily ≤20 and 21-30 years old), and from the Nursing Sciences Department (35.5%). Females were more likely to experience moderate/severe anxiety compared to males (30.1% vs 17.8%), suggesting that gender influences anxiety levels. Younger participants (≤20 years old) also had higher levels of moderate/severe anxiety (36.0%) than older groups, indicating age as a key factor in anxiety severity. Radiography students showed the highest percentage of moderate/severe anxiety (28.9%) (Table 3). Older participants (31-40 years old) were significantly less likely to experience moderate or severe depression compared to the youngest group (7.4% vs 30.8%), indicating that depression severity varies with age.

No significant differences were found in depression severity across sexes, academic departments, or academic levels, suggesting that depression may not be strongly influenced by these demographic factors (Table 3).

Discussion

This study’s finding of higher moderate to severe anxiety among female students is consistent with previous research showing higher anxiety levels in females in academic settings [10, 11]. However, it highlights the importance of considering cultural influences, such as those specific to Ebonyi State. Socialization patterns may lead females to express emotional distress more readily than males, who may suppress symptoms due to cultural gender norms [12, 13]. This finding emphasizes the need for culturally sensitive anxiety assessments and challenges the limitations of universal approaches in diverse populations.

The lower depression prevalence observed in the youngest age group, compared to older students, contradicts research suggesting higher depression rates among adolescents and young adults [14, 15]. This result could be due to protective social support systems in Ebonyi State, which may buffer younger students from mental health impacts [15, 16]. This finding calls for further culturally specific investigations into depression among university students, as universal assumptions about age-related risks may not apply in all contexts.

The lack of a significant sex difference in depression prevalence contrasts with studies showing higher rates in females [17, 18]. This discrepancy could stem from cultural factors in Ebonyi State that discourage males from acknowledging distress, leading to underreporting of depressive symptoms. The sample size or limitations in measurement tools, such as the PHQ-9, may also explain the lack of observed gender differences.

Finally, the mental health challenges university students face in this study reflect broader trends in academic populations [10, 19]. Like previous research by Maeng & Milad [11] and Asher et al. [20], the study confirms that students in high-pressure fields like health sciences experience heightened anxiety and depression. These findings underscore the need for targeted mental health interventions, such as counseling and stress-management programs, to address the specific challenges faced by health science students, as supported by Hawes et al. [16].

Conclusion

This study reveals a concerning prevalence of anxiety and depression among health science students in Nigeria, highlighting the urgent need for specific mental health interventions tailored to their academic and clinical pressures. To support these students’ well-being and educational success, universities should implement counseling services, peer support programs, and stress-management workshops. These interventions should address health science students’ unique stressors, such as clinical rotations, academic workload, and exposure to high-stress environments.

Recommendations

Future research should investigate the impact of specific stressors, particularly clinical rotations and academic workload, on mental health outcomes. Additionally, exploring the role of institutional support systems, such as mentorship, peer support, and faculty engagement, could provide valuable insights into effective interventions. To address the limitations of this study, future research should consider longitudinal designs to track changes over time and use larger, more diverse samples to enhance generalizability.

Implications for policymakers

We recommend prioritizing mental health in academic institutions through the implementation of mandatory mental health screenings for all students, especially those in high-stress programs like health sciences, ensuring adequate funding and staffing for mental health counseling services on campus, and organizing awareness campaigns to reduce stigma associated with mental health issues and encourage help-seeking behavior.

We suggest integrating mental health into curricula by incorporating mental health education, emphasizing stress management, coping strategies, and self-care techniques. We also recommend implementing flexible academic policies to accommodate students’ mental health needs, such as extensions on assignments and exams.

Finally, support for vulnerable groups must be provided through the development of targeted interventions for female and younger students who are at higher risk of anxiety, fostering peer support programs to provide emotional support and reduce feelings of isolation.

Implications for the public

Reduce stigma by challenging negative stereotypes and misconceptions about mental illness.

Promote open dialogue by encouraging open conversations about mental health to normalize seeking help.

Support mental health initiatives by advocating for increased funding and resources for mental health services.

Practice self-care by prioritizing self-care practices like mindfulness, exercise, and adequate sleep.

Limitations of the study

This study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships, and longitudinal studies are needed to track changes in mental health over time. The self-report nature of the study may also introduce social desirability bias, potentially underestimating the true prevalence of mental health issues. Although the sample size of 383 participants provides a solid foundation, it may not fully represent Southeast Nigeria’s broader population of health science students. A larger sample size could enhance the generalizability of the findings and uncover additional data nuances.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the College of Health Sciences Ethical Research Committee Evangel University Akaeze, Ebonyi State, Nigeria (Code: EU/CHERC/2022).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing the original draft and project administration: Odochi Chukwu and Maryjoy Umoke; Formal analysis and resources: Odochi Chukwu; Investigation, review and editing: Odochi Chukwu and Cordilia Iyare; Supervision and validation: Maryjoy Umoke.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for contributing to the research.

References

- AlJaber MI. The prevalence and associated factors of depression among medical students of Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2020; 9(6):2608-14. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_255_20] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Almalki SA, Almojali AI, Alothman AS, Masuadi EM, Alaqeel MK. Burnout and its association with extracurricular activities among medical students in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Medical Education. 2017; 8:144-50. [DOI:10.5116/ijme.58e3.ca8a] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Alotaibi AD, Alosaimi FM, Alajlan AA, Bin Abdulrahman KA. The relationship between sleep quality, stress, and academic performance among medical students. Journal of Family & Community Medicine. 2020; 27(1):23-28. [DOI:10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_132_19] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Almutairi H, Alsubaiei A, Abduljawad S, Alshatti A, Fekih-Romdhane F, Husni M, et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2022; 68(6):1157-70. [DOI:10.1177/00207640221106691] [PMID]

- Abdel Wahed WY, Hassan SK. Prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety and depression among medical Fayoum University students. Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 2017; 53(1):77-84. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajme.2016.01.005]

- Abu Ruz ME, Al-Akash HY, Jarrah S. Persistent (anxiety and depression) affected academic achievement and absenteeism in nursing students. The Open Nursing Journal. 2018; 12:171-9. [DOI:10.2174/1874434601812010171] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959; 32(1):50-5. [DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x] [PMID]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Williams JBW. Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). New York: APA PsycTests; 1999. [DOI:10.1037/t06165-000]

- AlHadi AN, AlAteeq DA, Al-Sharif E, Bawazeer HM, Alanazi H, AlShomrani AT, et al. An arabic translation, reliability, and validation of Patient Health Questionnaire in a Saudi sample. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2017; 16:32. [DOI:10.1186/s12991-017-0155-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Asif S, Mudassar A, Shahzad TZ, Raouf M, Pervaiz T. Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among university students. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020; 36(5):971-76. [DOI:10.12669/pjms.36.5.1873]

- Maeng LY, Milad MR. Sex differences in anxiety disorders: Interactions between fear, stress, and gonadal hormones. Hormones and Behavior. 2015; 76:106-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.04.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McHenry J, Carrier N, Hull E, Kabbaj M. Sex differences in anxiety and depression: Role of testosterone. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2014; 35(1):42-57. [DOI:10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.09.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shields S. Gender and emotion: What we think we know, what we need to know, and why it matters. Psychology of Women Quarterly 2013; 37(4):423-35. [DOI:10.1177/0361684313502312]

- Van Droogenbroeck F, Spruyt B, Keppens G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry. 2018; 18(1):6. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1591-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Högberg B, Strandh M, Hagquist C. Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years-The role of school-related stress. Social Science & Medicine. 2020; 250:112890. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112890] [PMID]

- Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Klein DN, Hajcak G, Nelson BD. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine. 2022; 52(14):3222-30. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291720005358] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kuehner C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry. 2017; 4(2):146-58. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2] [PMID]

- Cavanagh A, Wilson CJ, Kavanagh DJ, Caputi P. Differences in the expression of symptoms in men versus women with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2017; 25(1):29-38. [DOI:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000128] [PMID]

- Arslan C, Oral T, Karababa A. [Examination of Secondary School Students’ Hope Levels in terms of Anxiety, Depression and Perfectionism (Turkish)]. TED EğitimveBilimDergisi 2018; 43(194):421-30. [DOI:10.15390/EB.2018.6592]

- Asher M, Asnaani A, Aderka IM. Gender differences in social anxiety disorder: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2017; 56:1-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.05.004] [PMID]

Type of Study: Short Communication |

Subject:

● Psychosocial Health

Received: 2024/11/27 | Accepted: 2025/01/19 | Published: 2025/07/1

Received: 2024/11/27 | Accepted: 2025/01/19 | Published: 2025/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |