Volume 15, Issue 6 And S7 (Artificial Intelligence 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(6 And S7): 661-682 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: NOT (Review article)

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Keykha A, Hojati M, Taghavi Monfared A, Shahrokhi J. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Unveiling Ethical Challenges Through Meta-synthesis of Evidence. J Research Health 2025; 15 (6) :661-682

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2834-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2834-en.html

1- Department of Educational Administration, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Kharazmi University, Karaj, Iran. , ahmad.keykha72@sharif.edu

2- Department of General Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, Guilan University, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Educational Administration and Planning, Faculty of Psychology and Education, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of General Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, Guilan University, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Educational Administration and Planning, Faculty of Psychology and Education, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence (AI), Ethical challenges, Healthcare, Meta-synthesis, Medical ethics

Full-Text [PDF 1184 kb]

(292 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2138 Views)

Full-Text: (16 Views)

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has created unprecedented opportunities across diverse sectors, with particularly transformative impacts in medicine, healthcare education, and biomedical research. From personalized treatment recommendations and predictive diagnostics to intelligent tutoring systems and robotic-assisted surgeries, AI has rapidly evolved from a novel technological tool to a central component of contemporary medical ecosystems [1–4]. These developments promise increased efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility in clinical services and educational platforms alike.

However, the swift integration of AI into healthcare systems has simultaneously raised substantial ethical concerns. These include, but are not limited to, challenges related to algorithmic bias, the opacity of decision-making processes (“black-box” models), data privacy violations, the erosion of professional autonomy, legal ambiguities regarding responsibility and liability, and the risk of deskilling among healthcare practitioners [5–8]. For instance, when AI is used to augment or replace clinical decision-making, there is a growing fear that health professionals may lose core competencies over time and become overly reliant on algorithmic tools, thus compromising the development of sound clinical judgment and reducing physician-patient trust [9, 10].

Moreover, AI-generated content, whether in research or clinical documentation, raises questions about authorship, intellectual property rights, and the blurring boundaries between human and machine-generated outputs. These concerns are compounded by global disparities in access to AI technologies and the risk that such tools may exacerbate existing health inequities if not carefully monitored and ethically deployed.

Although there is a growing body of scholarship discussing the ethical implications of AI in medicine, a significant gap remains in terms of synthesizing qualitative insights from diverse empirical and review studies. Most existing analyses tend to focus on specific ethical domains (e.g. data protection or transparency), while neglecting the interconnectedness and complexity of ethical issues across real-world healthcare settings. Furthermore, few studies have systematically integrated qualitative findings from multiple perspectives—including patients, clinicians, developers, and ethicists—through a rigorous interpretive synthesis.

Given the ethical weight and social ramifications of AI deployment in healthcare, a more comprehensive and methodologically grounded understanding of these challenges is urgently needed. This study addressed this gap by conducting a qualitative meta-synthesis of peer-reviewed research, guided by the principles of thematic synthesis and informed by the PRISMA framework. Our objective was to identify the ethical challenges associated with the implementation of AI in healthcare. By consolidating diverse qualitative evidence into a coherent analytical framework, this study aimed to strengthen the theoretical and practical foundations for ethical AI governance in health systems.

Methods

We conducted a thematic synthesis of qualitative and review studies in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. We included qualitative and review studies that focused on the ethical challenges associated with the application of AI in healthcare. Study appraisal involved the use of a validated quality assessment tool [11]. Thematic synthesis techniques [12] were employed for analysis and synthesis, and the GRADE-CERQual approach [13] was applied to assess the confidence in the review findings.

Criteria for inclusion

A comprehensive and systematic search strategy was developed in consultation with an academic librarian. Searches were performed across four major electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Each search included combinations of controlled vocabulary (e.g. MeSH terms) and free-text keywords related to AI, ethics, and healthcare, alongside filters for qualitative and review studies. The search strategy for each database was tailored to its syntax and structure. Searches were conducted between May 15, 2010, and 2015.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify relevant studies across major academic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search combined controlled vocabulary terms and free-text keywords related to AI, ethics, and healthcare. Specifically, the following search terms were used: (“AI” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “AI”) AND (“ethics” OR “ethical issues” OR “ethical challenges” OR “ethical considerations” OR “bioethics”) AND (“healthcare” OR “health care” OR “medicine” OR “clinical practice” OR “medical ethics”) AND (“qualitative study” OR “qualitative research” OR “systematic review” OR “narrative review” OR “thematic synthesis”).

Study selection

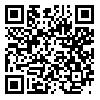

All retrieved records were organized using Microsoft Excel, where duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening was conducted by two independent reviewers (Ahmad Keykha and Ava Taghavi Monfared) in duplicate for an initial subset of articles to ensure consistency in applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. The remaining articles were then equally divided and screened individually. Full-text assessments were conducted independently by the same two reviewers, and disagreements were resolved through consensus with input from a third reviewer (Jafar Shahrokhi and Maryam Hojati) when needed. During the study selection process, all retrieved records were imported into Microsoft Excel. After removing duplicates and retracted articles (n=10), titles (n=89) and abstracts (n=56) were screened. This resulted in 78 articles for full-text review. These reasons are reflected in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

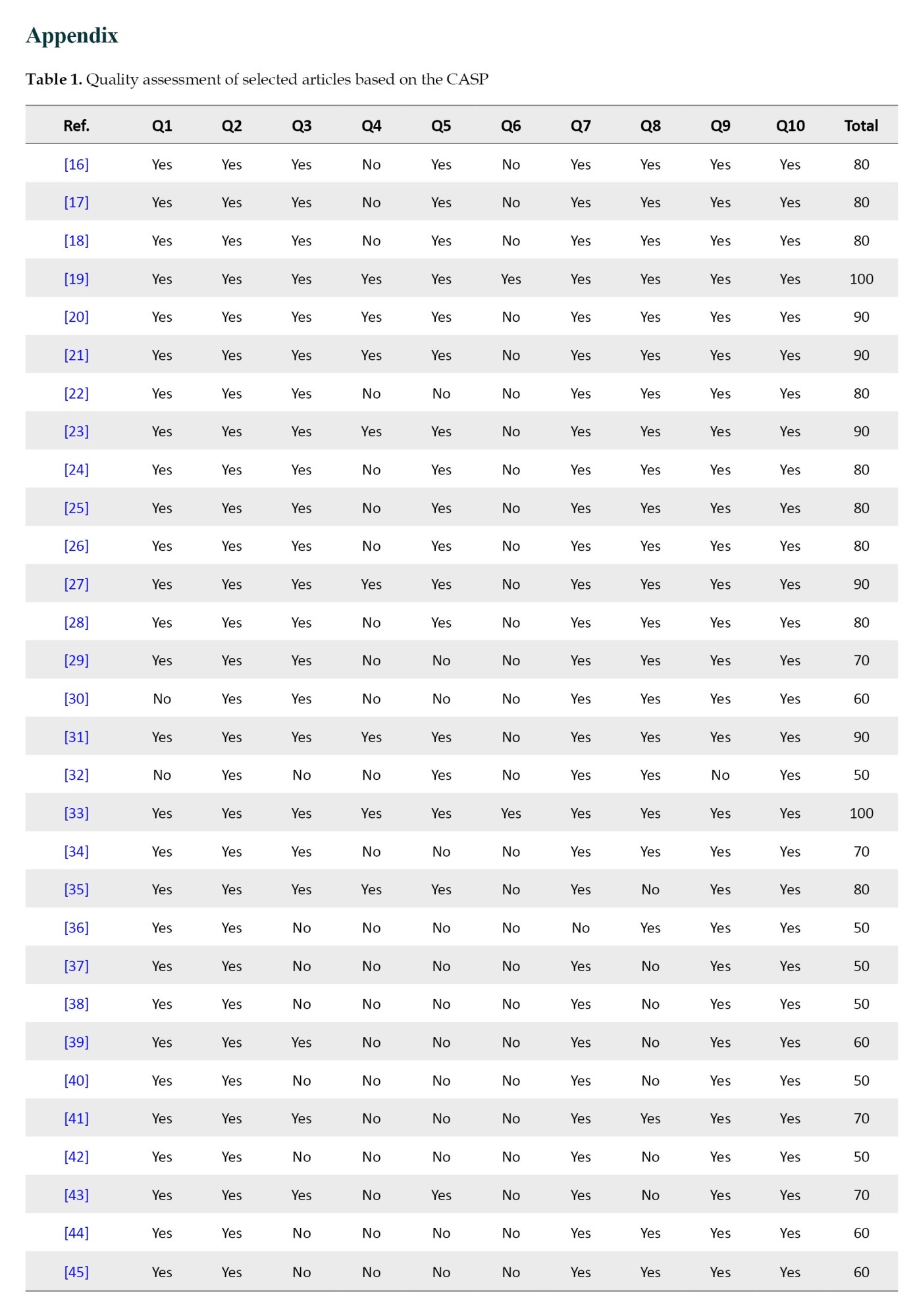

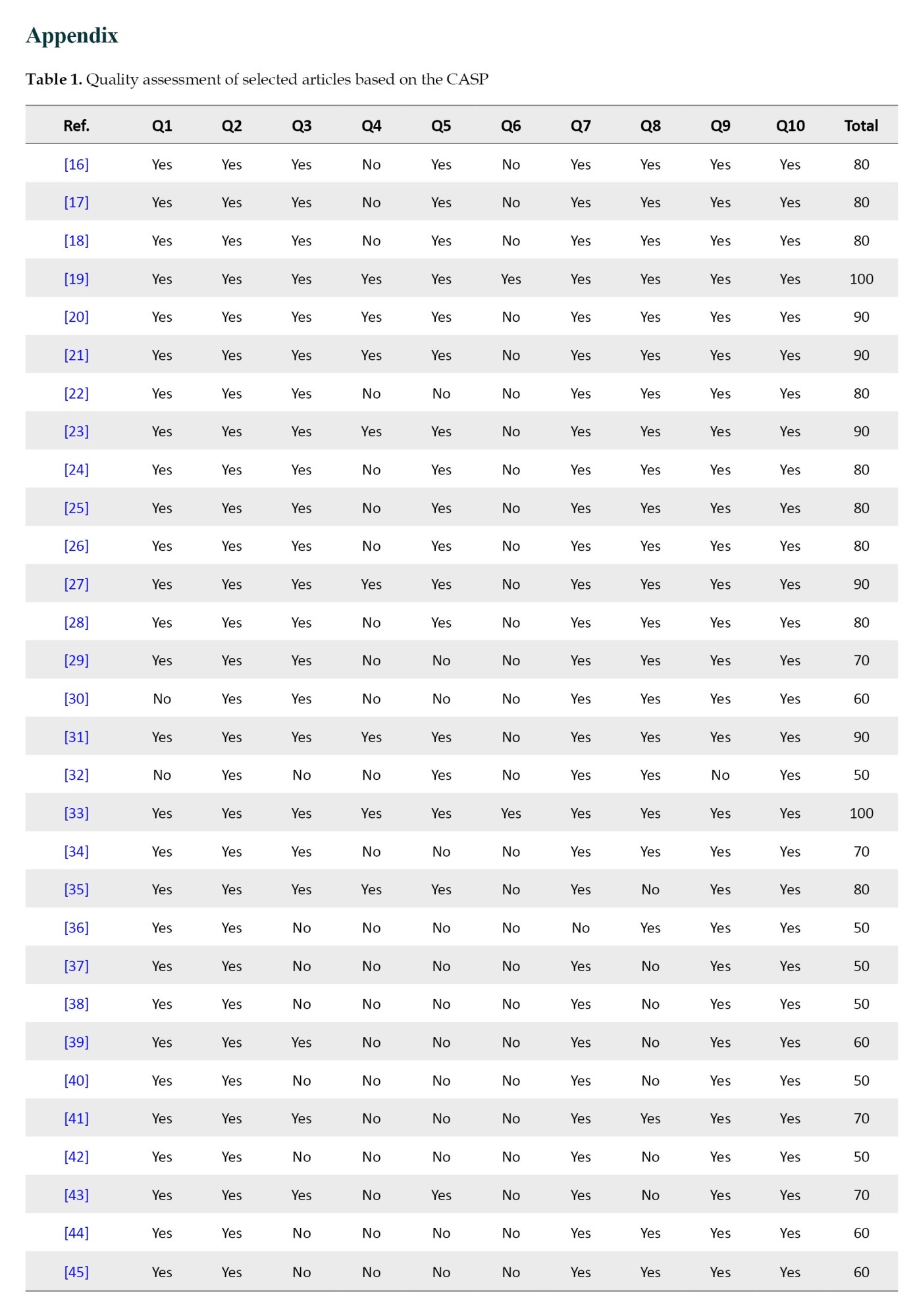

To assess the methodological rigor of included studies, we employed the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) qualitative checklist [14], which includes ten standard questions evaluating aspects, such as study design, data collection, ethical considerations, and validity of findings. Each question was scored as either “yes”=10, “no”=0, or “can’t tell”=5. thus, the maximum possible score for each study was 100. No differential weighting was applied to individual items. The “Total” score represents the cumulative sum of the ten individual question scores. Studies scoring (below 50) were considered methodologically weak and were excluded from the final thematic synthesis. However, they are reported for transparency and completeness. The quality appraisal was conducted independently by two reviewers (Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi), and disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (Maryam Hojati) (Appendix 1).

Risk of bias assessment

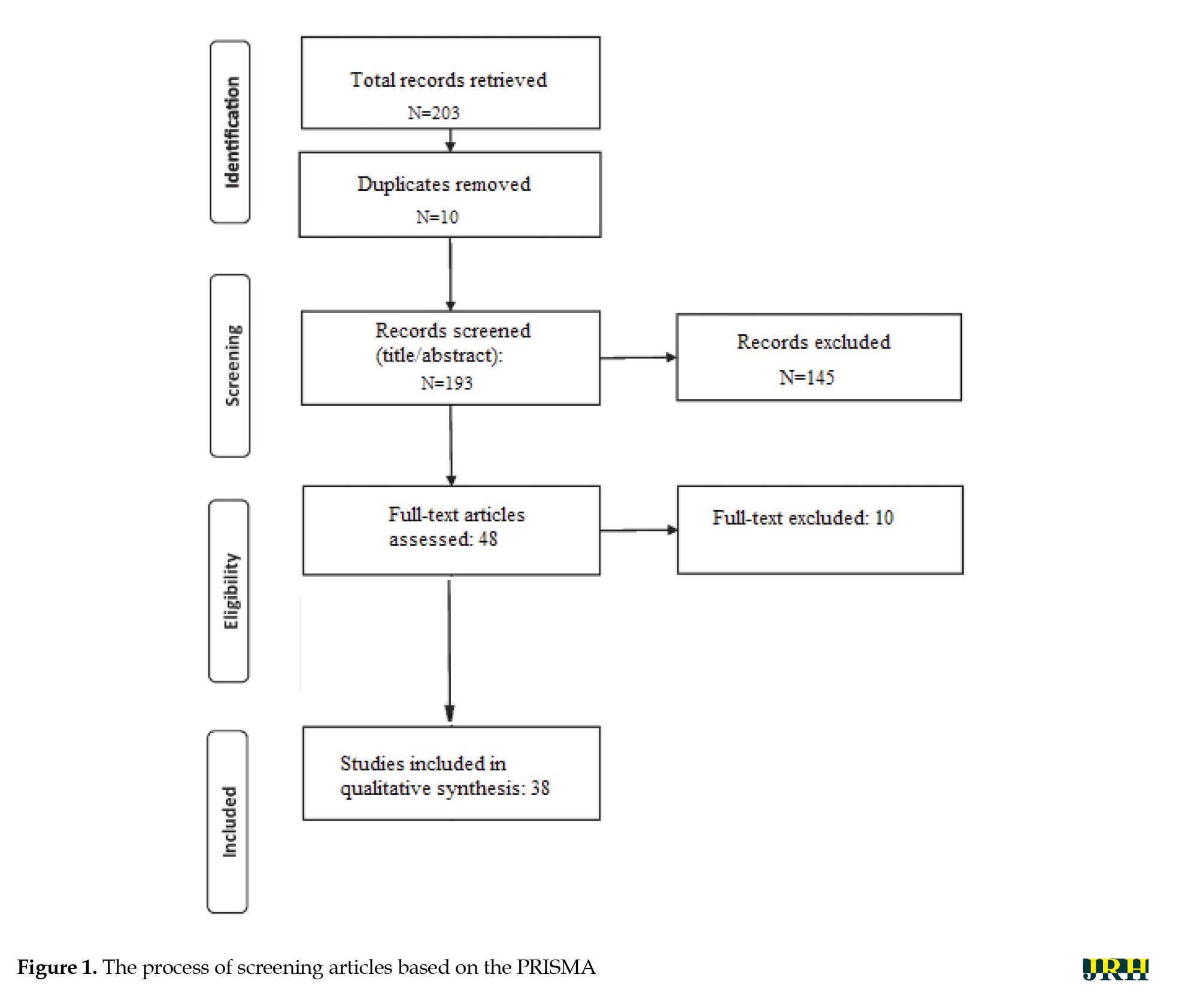

To evaluate the risk of bias in the included studies, we employed the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for qualitative and review studies, supplemented by the ROBIS framework [15] for systematic reviews. The assessment focused on key domains, including study selection, data collection methods, clarity of ethical considerations, transparency in reporting, and potential conflicts of interest. Each study was independently assessed by two reviewers (Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi), with discrepancies resolved by consensus or by consultation with a third reviewer (Maryam Hojati). The results of the risk of bias assessment are summarized in Figure 2, using a traffic-light system (green=low risk, yellow=unclear risk, red=high risk). This visual representation provides a transparent overview of the methodological soundness and credibility of the included studies.

Data extraction and analysis

The analysis was guided by the core principles of thematic synthesis [12]. Data extraction and thematic development were performed by two researchers (Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi) working in parallel. Themes were developed inductively following the principles of thematic synthesis, rather than based on an a priori framework. The key findings and themes reported in this index paper were systematically coded and organized within a spreadsheet, forming the basis of an initial thematic framework. As subsequent studies were reviewed, their findings were coded and integrated into this evolving framework, which was refined iteratively as new data were incorporated. The analysis involved identifying patterns across studies, while also actively seeking out contradictory or disconfirming data—evidence that challenged either the emerging themes or the reviewers’ prior assumptions. This step was essential in ensuring the robustness of the synthesis. Data extraction and thematic development occurred in parallel.

Data validation

To ensure the reliability of the extracted concepts, the primary researcher compared their interpretations with those of an expert in the field. Inter-rater agreement was then assessed using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, yielding a value of k=0.664, with a significance level of P=0.001. According to the interpretation guidelines provided by Jensen and Allen [54], this level of agreement is considered acceptable, indicating substantial consistency between raters.

Results

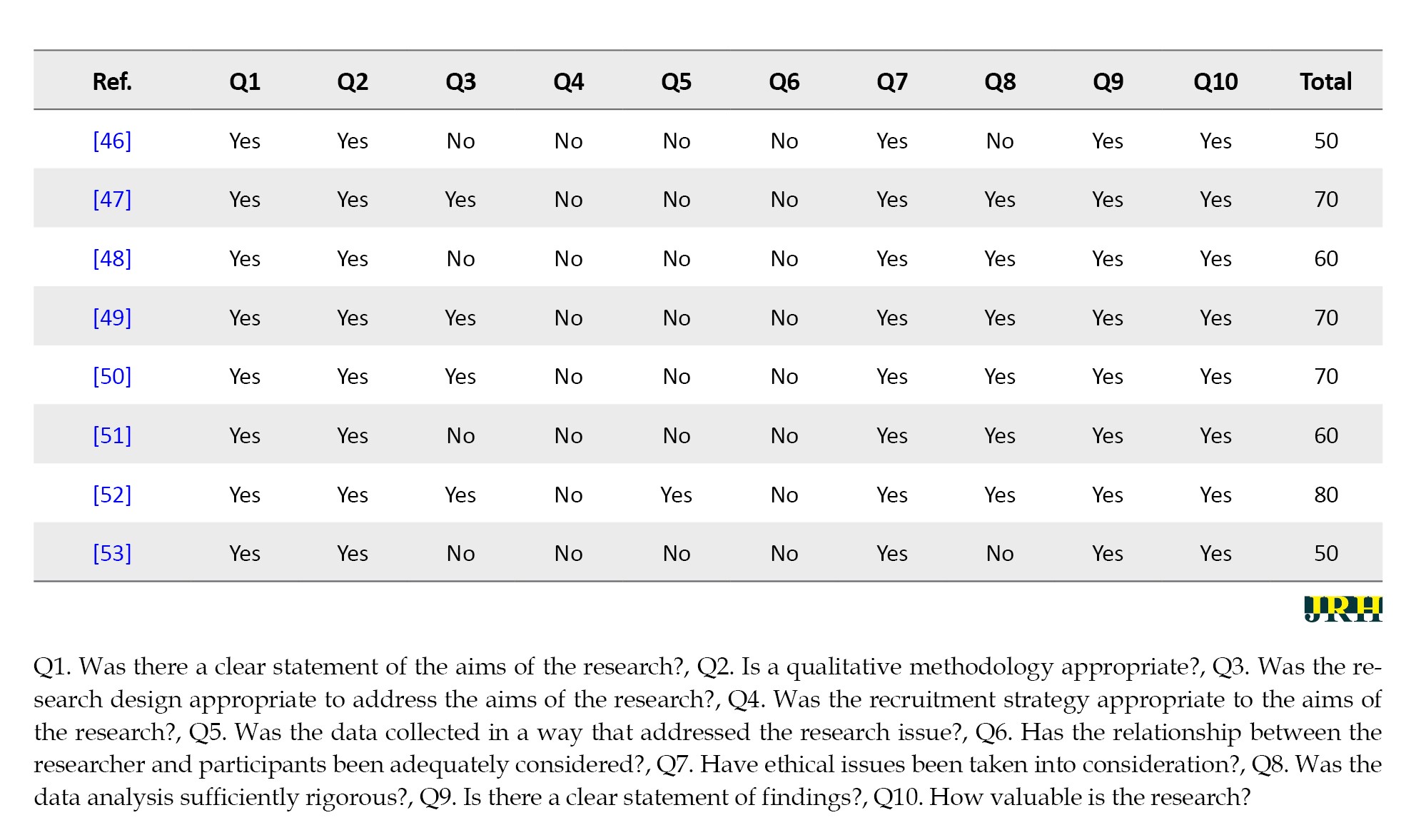

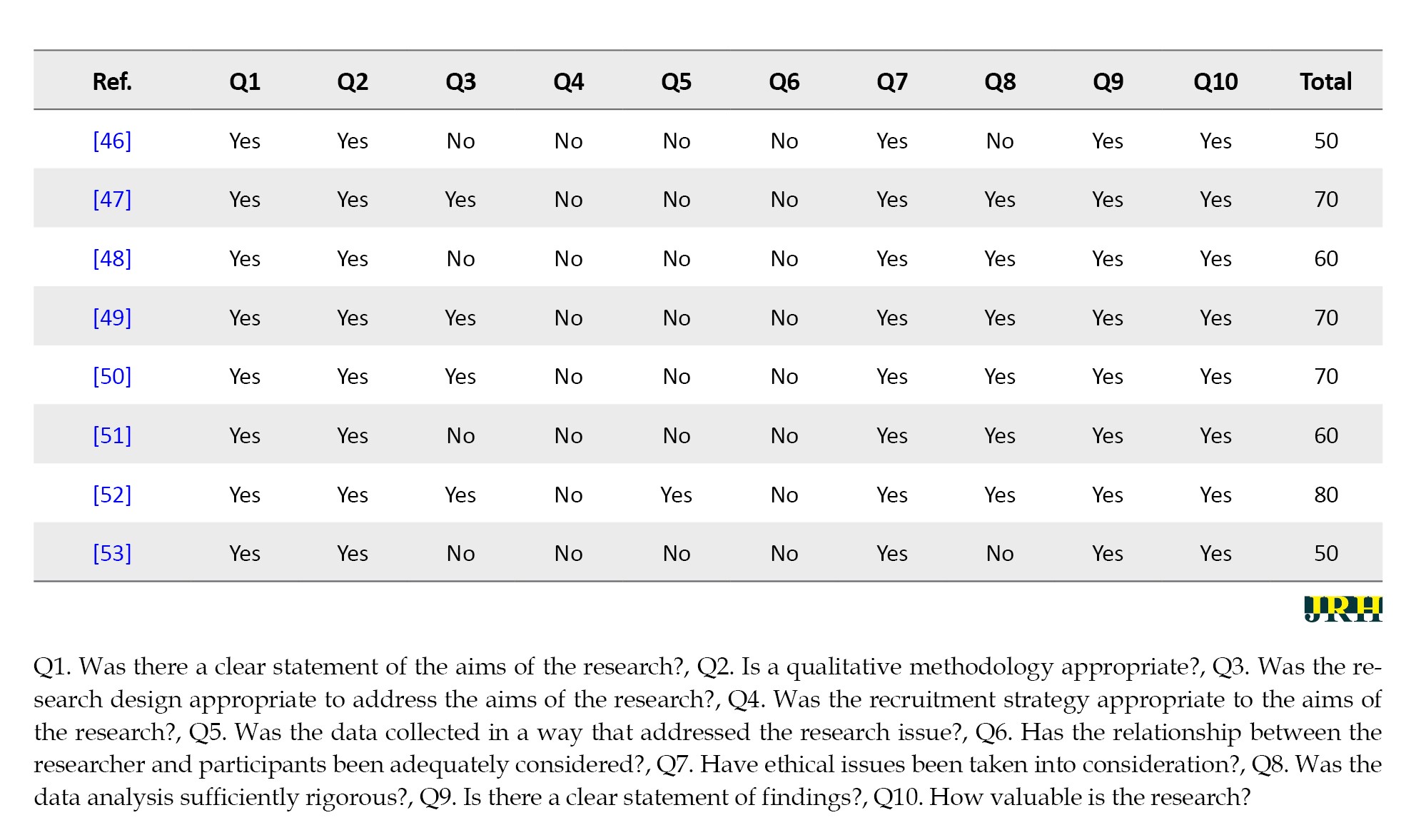

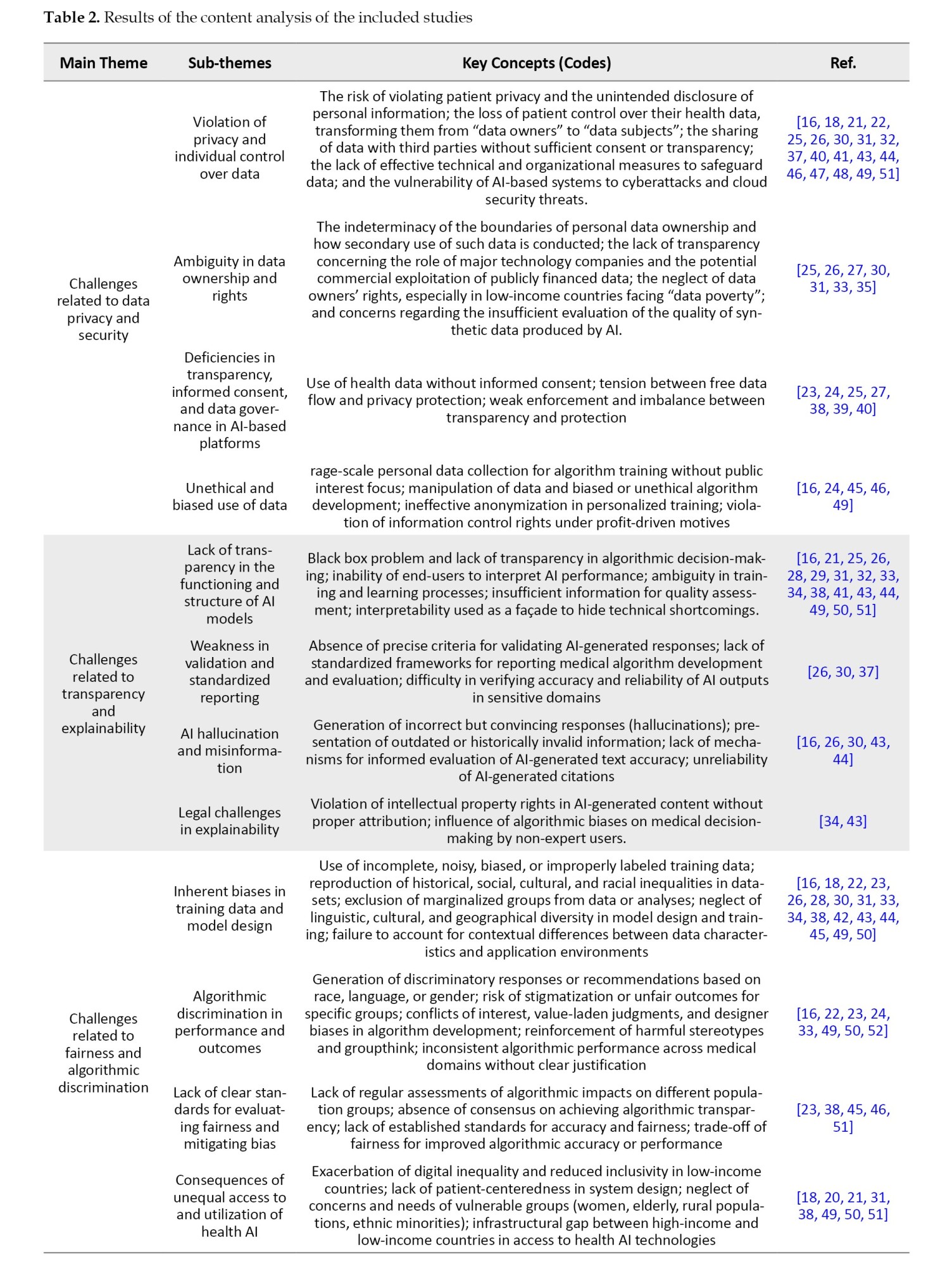

The inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in this review were predefined according to the PICOS framework, as summarized in Table 1.

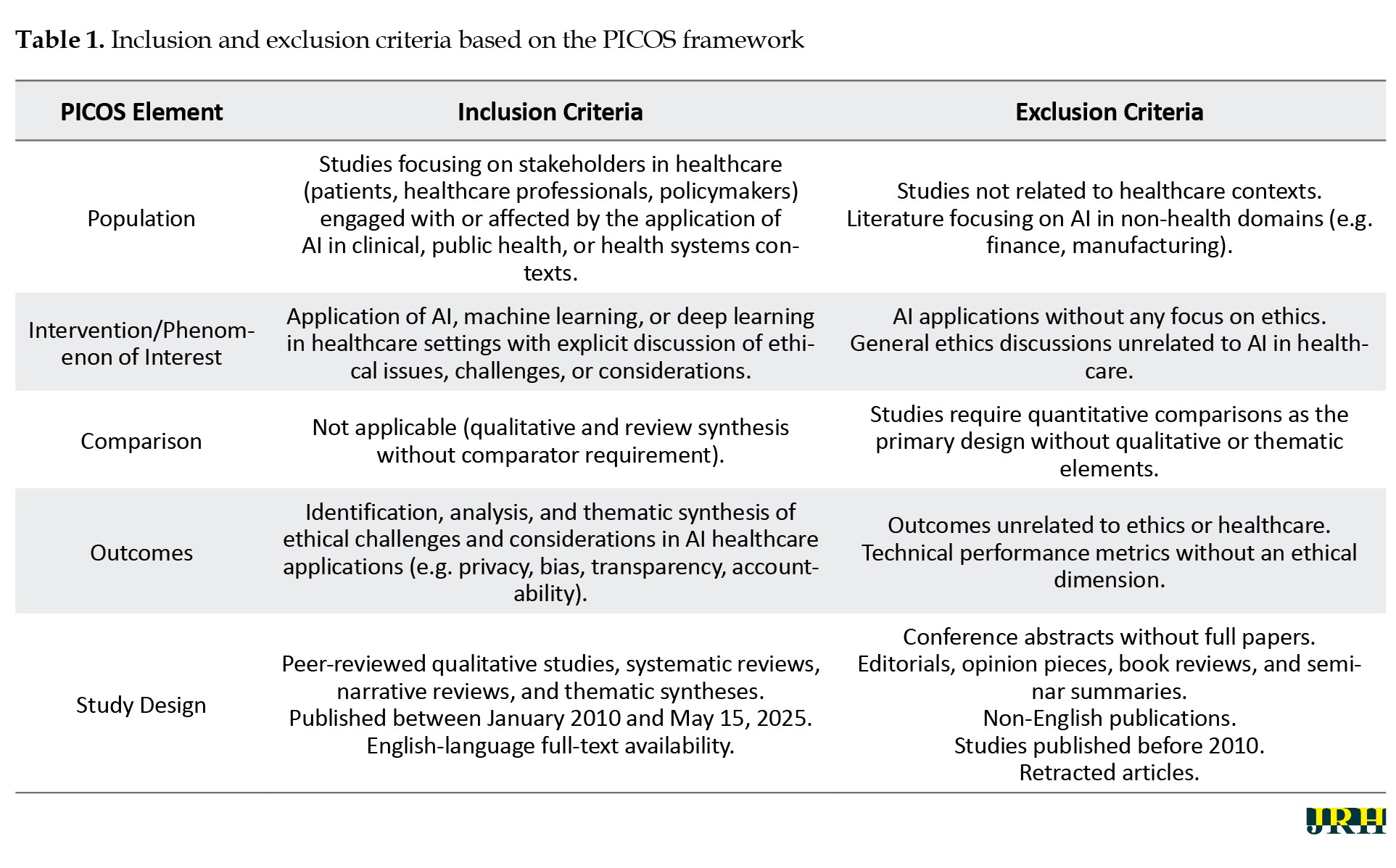

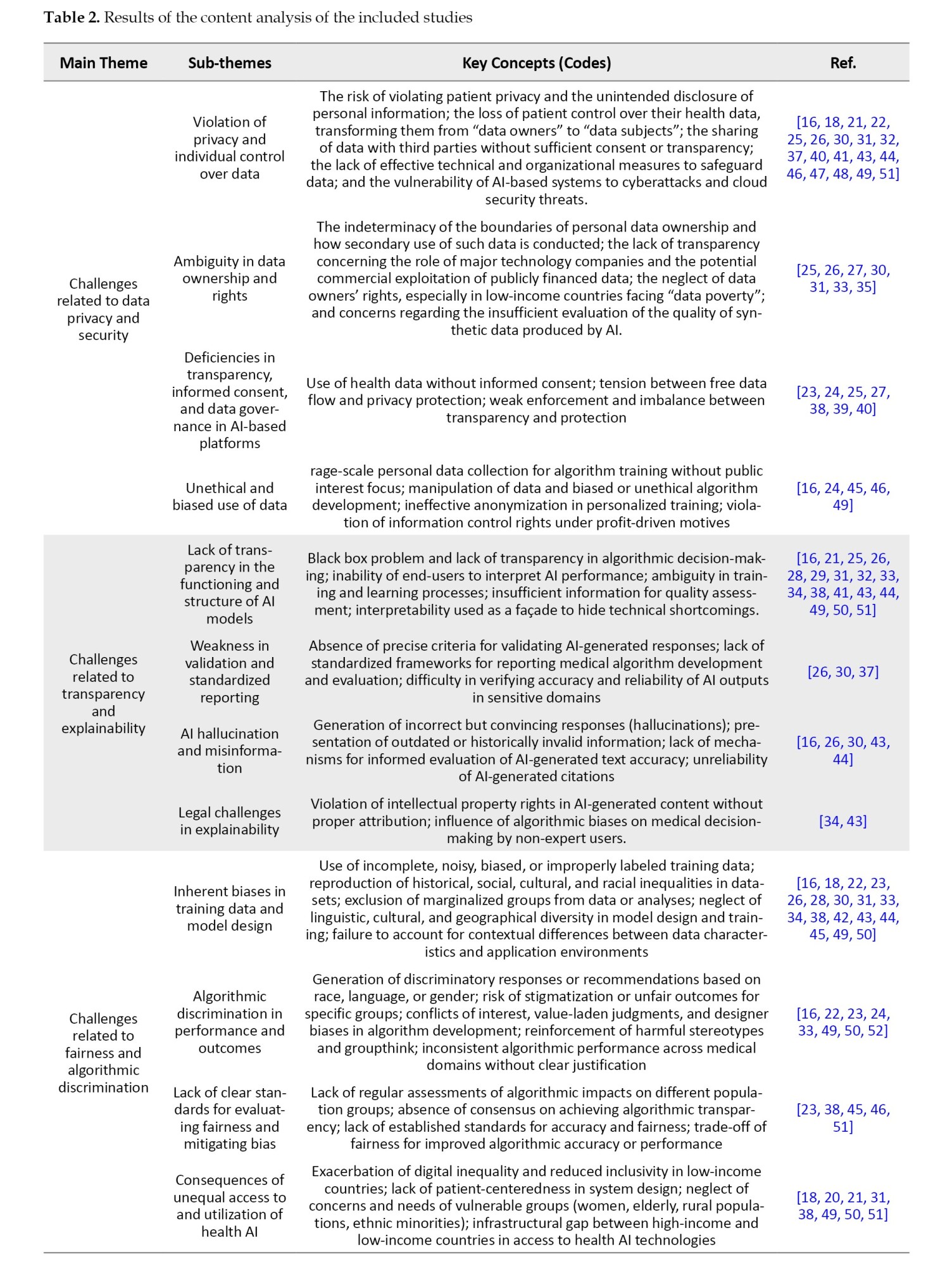

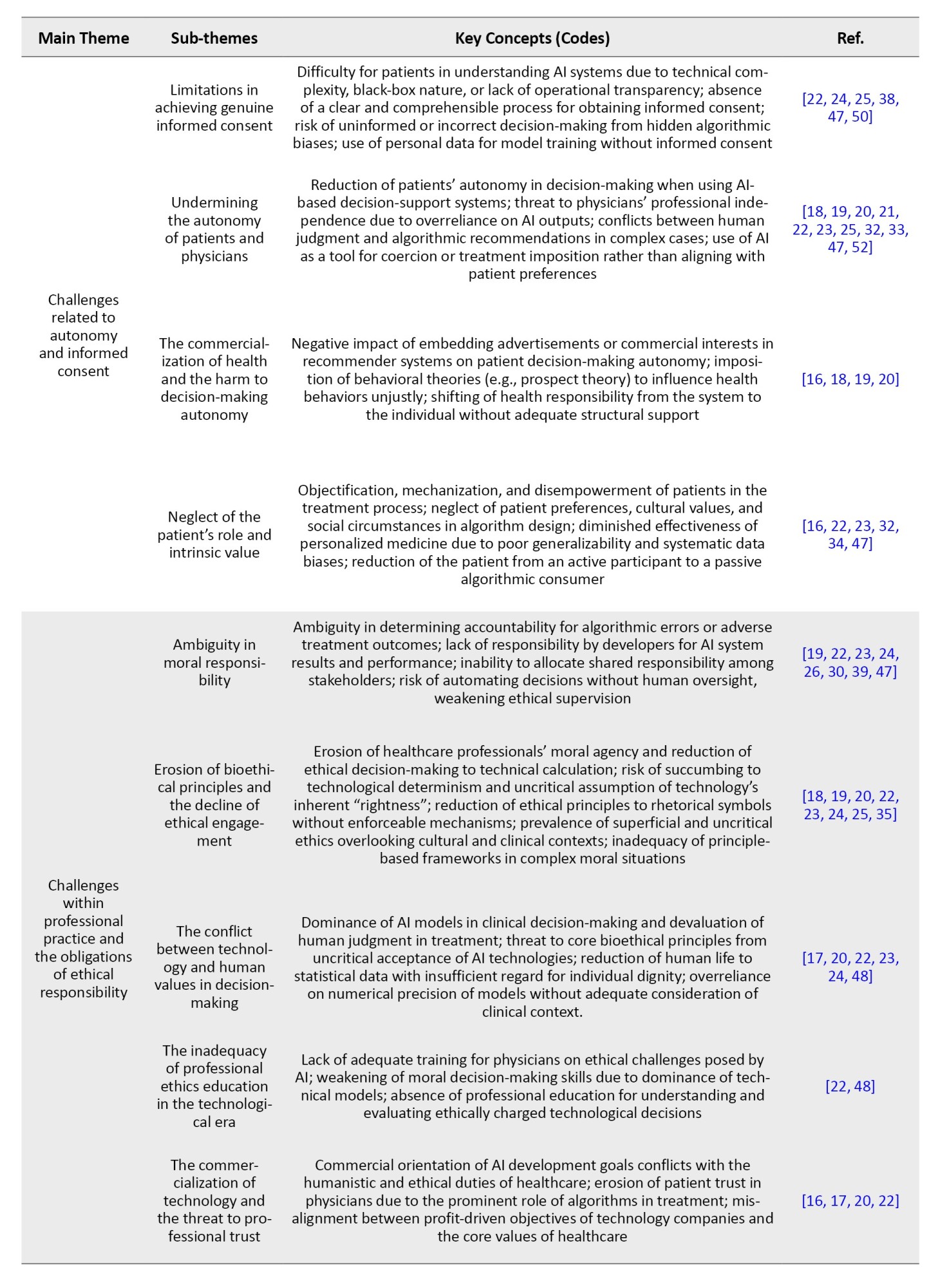

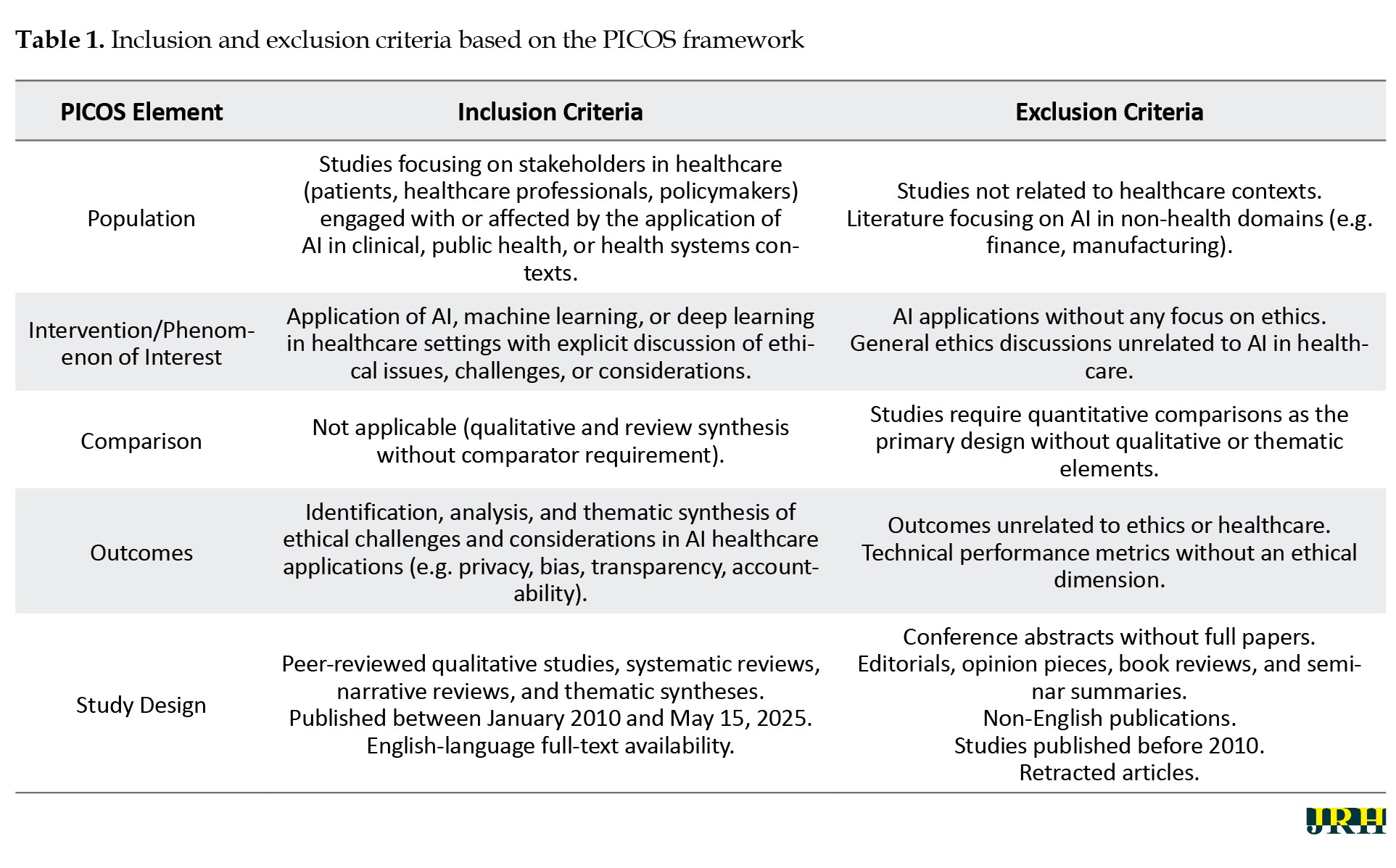

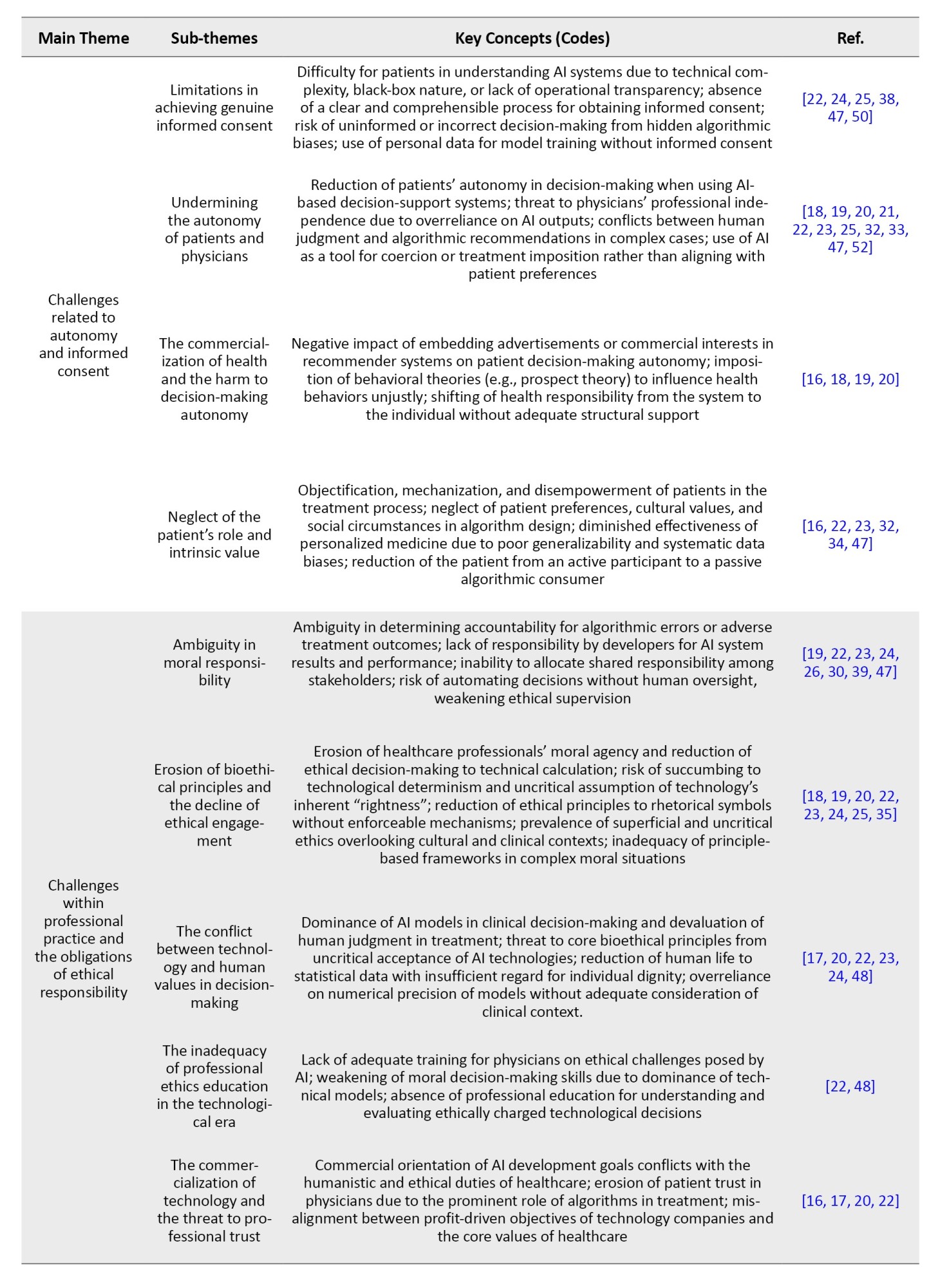

Table 2 presents the results of the content analysis of the reviewed articles.

The process involved initially extracting key codes or concepts. These codes were then categorized into sub-themes based on their similarities and differences. Subsequently, the sub-themes were grouped into main themes through a similar comparative analysis. Table 2 comprises six main themes, each further divided into sub-themes based on topical similarity. For each main theme and its corresponding sub-themes, the key concepts constituting that theme are presented, accompanied by reference numbers indicating the supporting sources.

The content analysis revealed that the most frequently addressed theme, cited in over 35 studies, concerns challenges related to data privacy and security, underscoring a widespread concern regarding the control, ownership, and protection of health data in AI-based platforms. AI systems need large amounts of sensitive information to make decisions, such as medical history, genetic data, or mental health records. However, it is often unclear how this data is collected, stored, or used. Without proper safeguards, data may be misused or leaked. If patients do not trust the safety of their data, they may reject the use of AI in healthcare settings.

Closely following this are transparency and explainability challenges, highlighted in over 32 studies, particularly focusing on the “black box” nature of algorithms and the lack of standardized validation protocols for algorithms, especially those based on deep learning, which often work like a “black box,” meaning users cannot understand how the system makes decisions. This lack of transparency makes it difficult for doctors to explain AI-based diagnoses or treatment recommendations to patients. When decisions are not clearly explained, both medical professionals and patients may lose trust in the system. Improving explainability is essential for the responsible and accepted use of AI in medicine.

Issues of fairness and algorithmic discrimination were found in approximately 28 studies, with emphasis on biased datasets and the exclusion of marginalized populations. AI systems can unintentionally act in unfair or biased ways toward certain social or ethnic groups. This usually happens when the training data is not diverse enough. For example, the algorithm may work well for young men but perform poorly for women, the elderly, or minority populations. Such biases can lead to unequal access to quality care and may even worsen existing health disparities. Ensuring fairness requires using inclusive, representative datasets.

Autonomy and informed consent challenges were identified in 25 studies, raising alarms about the diminishing decision-making power of patients and physicians. The growing use of AI in healthcare can limit the decision-making power of both doctors and patients. In many cases, the system recommends without explaining the process, and the patient may feel forced to accept it. This can reduce the patient’s ability to make informed and independent choices. Respecting patient autonomy means ensuring that patients understand the AI’s role and have real options in their care decisions.

Ethical concerns tied to professional responsibility emerged in 22 studies. The use of AI in clinical environments raises questions about who is responsible when something goes wrong. If an AI system makes a harmful mistake, it is often unclear whether the doctor, the software developer, or the technology provider is accountable. This lack of clarity can reduce trust and make legal or ethical follow-up difficult. Clear rules are needed to define responsibility and ensure accountability in AI-assisted medical decisions.

Legal and regulatory gaps and clinical reliability issues were addressed in around 20 and 18 studies, respectively. Many countries still lack clear legal frameworks for regulating the use of AI in healthcare. There are few standards for evaluating the safety, effectiveness, or transparency of these systems. As a result, some technologies are used without proper oversight, increasing the risk of harm. Policymakers must create strong, future-oriented regulations that address the unique challenges of AI in medicine. AI systems that perform well in laboratory settings may not work as reliably in real-world clinical environments. Factors such as poor data quality, patient diversity, or differences in local healthcare resources can affect performance. If the system is not carefully tested in real conditions, it may produce inaccurate or harmful results. Thorough validation in practical settings is essential before wide adoption in medical practice.

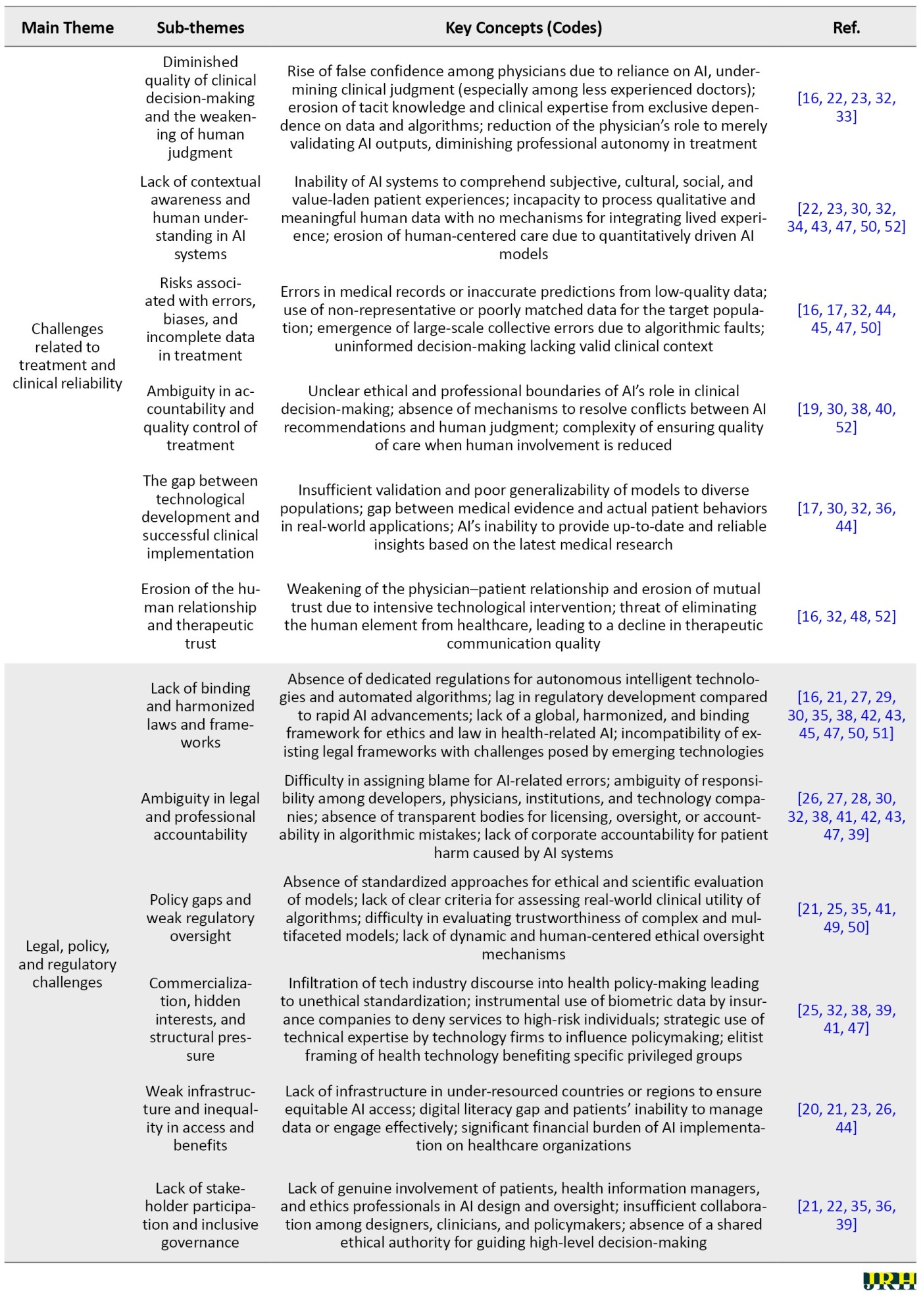

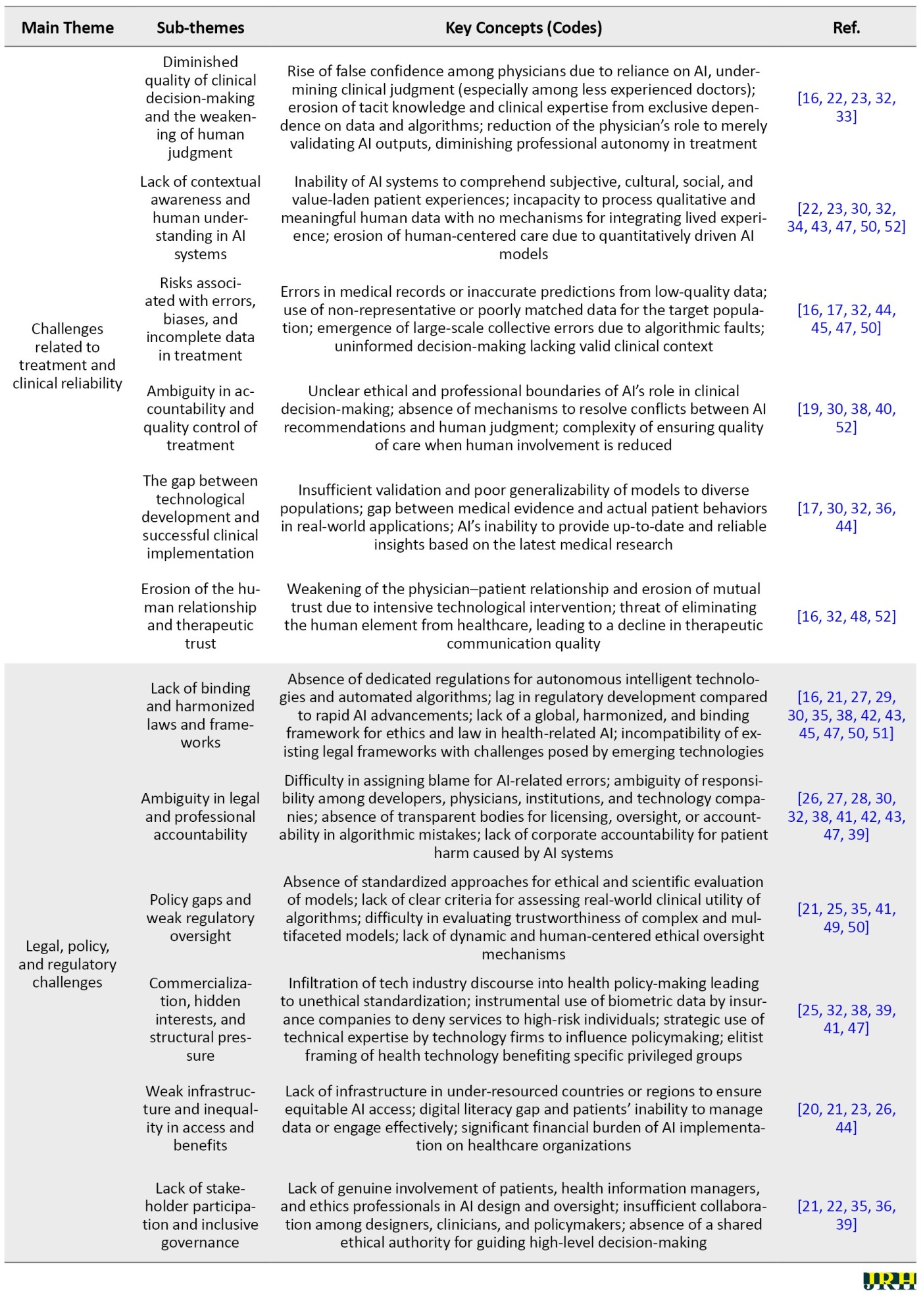

Table 3 summarizes the key ethical challenges identified in the reviewed literature, organized into six main themes.

Each theme is illustrated with a concise real-world or hypothetical case context to enhance practical relevance. For each case, Table 3 also outlines the associated policy or practice implications and provides a GRADE-CERQual confidence rating to indicate the strength of evidence and ethical severity. This structure enables readers to quickly grasp the nature of the challenge, its contextual manifestation, and its potential impact on healthcare systems.

The findings in Table 3 highlight the multi-dimensional nature of ethical challenges in AI-enabled healthcare, spanning privacy, transparency, fairness, autonomy, professional responsibility, clinical reliability, and regulatory governance. Data privacy and security risks underscore the urgent need for robust legal and technical safeguards, while transparency and explainability issues emphasize the necessity of mandatory disclosure and interpretability standards. Persistent algorithmic bias illustrates the deep-seated equity implications of AI, necessitating proactive dataset diversification and bias auditing. Challenges to autonomy reveal a pressing requirement for patient-centered consent processes that are both accessible and informative. Within professional practice, the absence of clear accountability mechanisms threatens ethical integrity, and in clinical contexts, reliability concerns demand rigorous validation and human oversight. Finally, the lack of harmonized legal frameworks not only undermines governance but also delays resolution in cases of harm. Collectively, these themes indicate that ethical AI integration in healthcare requires systemic, cross-disciplinary interventions that bridge technical, regulatory, and human-centered approaches.

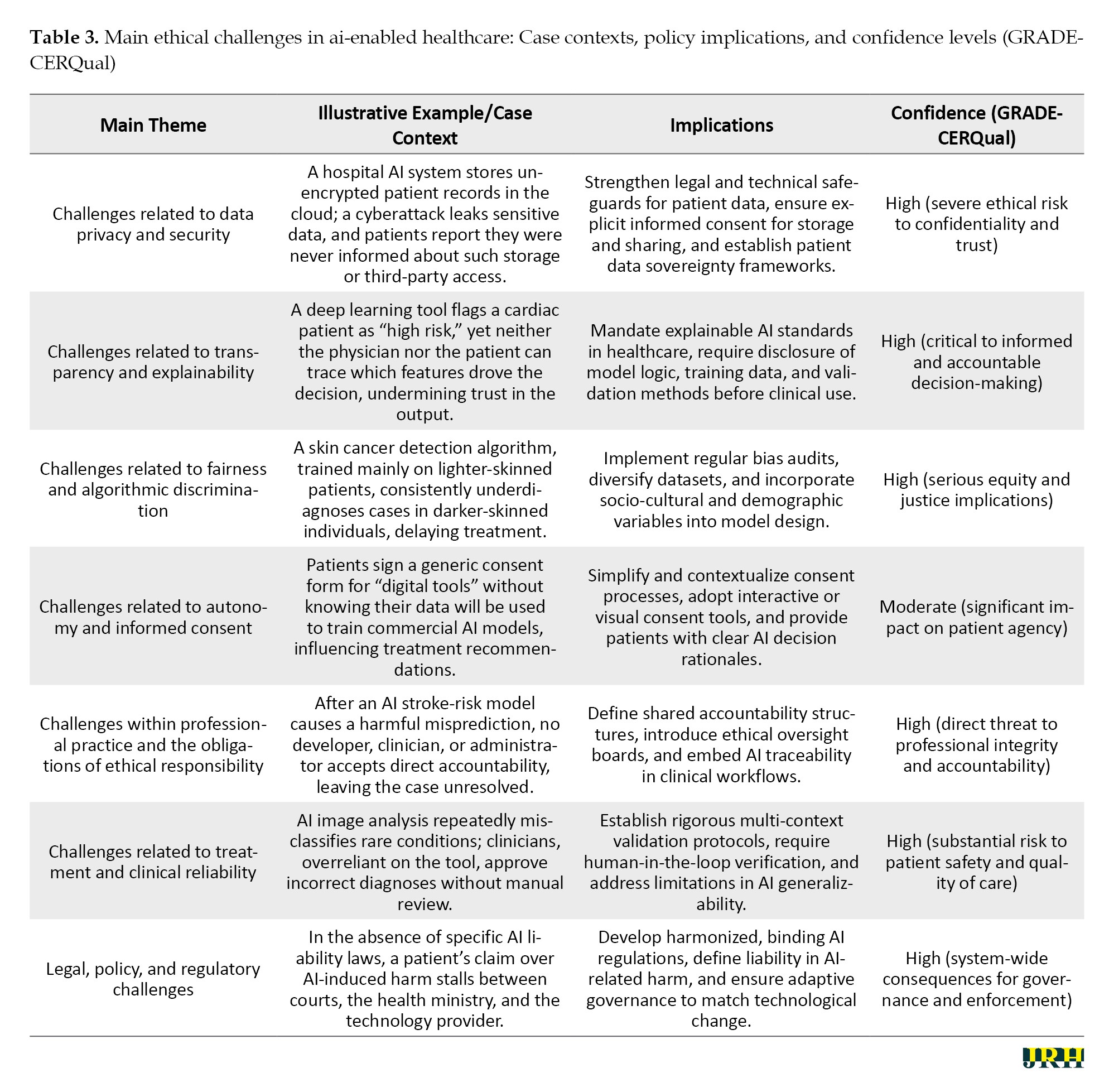

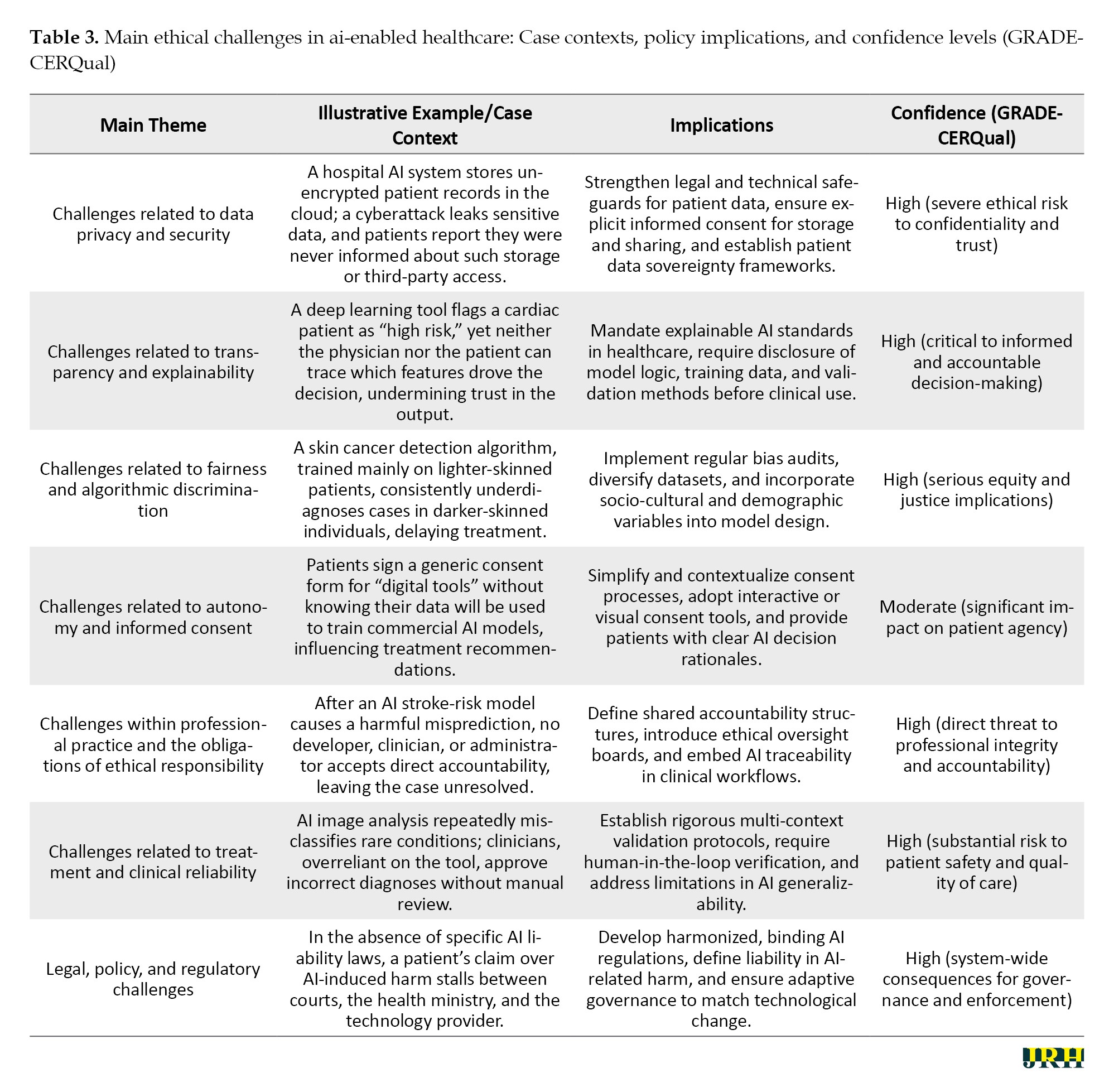

Comparison with existing reviews

In the following section of the findings, a comparative analysis of this meta-synthesis article with existing review studies on the ethical challenges of AI in healthcare is presented. Subsequently, Table 4 provides a summary of the review articles in this field.

In contrast to the reviews presented in Table 4, which are mostly in the form of narrative reviews, systematic reviews, or scoping reviews and whose primary focus is on compiling, categorizing, and descriptively presenting the findings of previous studies, the present research adopted an analytical–synthetic approach through the use of meta-synthesis and qualitative content analysis. This approach, in addition to collecting secondary data, reconstructed them through a systematic process involving coding, categorization, synthesis, and in-depth interpretation. Accordingly, the present study not only identified the common themes and patterns among previous research but also uncovered the gaps, contradictions, and shortcomings in the literature, ultimately offering an integrated analytical framework for a more comprehensive understanding of the ethical challenges of AI in healthcare. Therefore, while prior reviews mainly address the question of “what findings have been reported,” this meta-synthesis examined “how these findings interrelate, what conceptual connections exist among them, and what new pathways can be outlined for future research and policy-making.”

Discussion

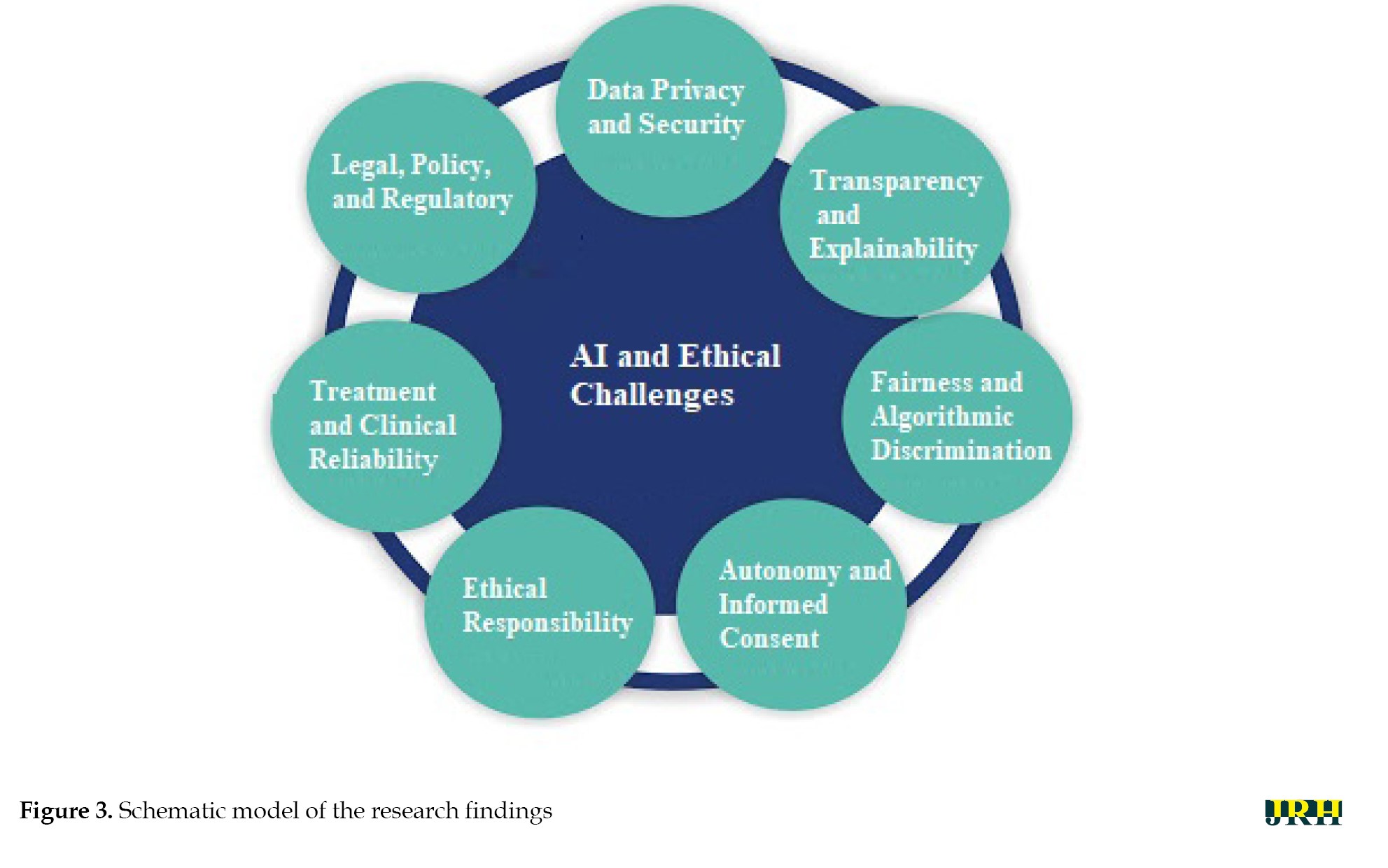

This study aimed to identify the ethical challenges of AI in healthcare. To achieve this objective, a content analysis was conducted on selected qualitative and review studies. In total, seven main themes and thirty-three sub-themes were identified. Figure 3 is a schematic model of the research findings.

Data privacy and security as the cornerstone of trust

In the field of AI, data privacy and security are not merely technical requirements but form the foundation of trust and stability in intelligent ecosystems. The quality and diversity of data, which underpin the learning and accuracy of algorithms, are meaningful only when users are confident that their information is stored and processed in a secure and controlled environment. This issue is especially critical in healthcare, where medical data reflect not only individuals’ physical conditions but also their psychological, social, and even genetic dimensions. Protecting this data directly influences technology acceptance, voluntary participation in innovative projects, and ultimately the pace of scientific advancement. In other words, data security in AI serves as a bridge linking innovation to public trust, and without it, even the most advanced algorithms will face distrust and social resistance. The findings of this section align with those reported in case studies [16, 18, 21-27, 30-33, 35, 37-41, 43-49, 51].

Transparency and explainability for accountability

In the field of AI, transparency and explainability constitute the backbone of trust, accountability, and social acceptance of the technology. Algorithms whose decision-making processes can be explained at a human-understandable level enable effective oversight, evaluation, and correction, preventing intelligent systems from becoming “black boxes.” This principle is especially critical in healthcare, where algorithmic decisions can directly impact patients’ lives and quality of care. When both clinicians and patients can comprehend the rationale behind a diagnosis or treatment recommendation, truly informed consent becomes possible, and accountability is strengthened at individual and institutional levels. Moreover, transparency and explainability not only serve as tools to detect errors and biases but also create a foundation for continuous learning and improvement of algorithms, fostering a constructive and trustworthy interaction between medical science and AI technology. The findings of this section align with those reported in studies [16, 21, 25, 26, 28-34, 37, 38, 41, 43, 44, 49-51].

Fairness and mitigation of algorithmic bias

In the realm of AI, fairness and algorithmic discrimination are intrinsically linked to social justice, equitable access to services, and the ethical legitimacy of technology. Algorithms reflect the data on which they are trained; therefore, if these datasets contain historical, social, or structural biases, intelligent systems may unintentionally reproduce and even amplify existing inequalities. In healthcare, this issue carries critical implications, from diagnostic errors in underrepresented population groups to inequitable allocation of treatment resources. Ensuring fairness in algorithms is not only an ethical imperative but also a prerequisite for public trust and clinical efficacy. Consequently, continuous monitoring, responsible data-driven design, and evaluation of social impacts are integral components of developing and deploying fair AI systems. The findings of this section are consistent with those presented in studies [16, 18, 20-24, 26, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 38, 42-44, 45, 46, 49-52].

Autonomy and informed consent in clinical practice

In the context of AI, autonomy and informed consent refer to preserving individuals’ right to make free decisions based on complete and transparent information. In medical applications, this principle ensures that patients are not only aware of AI-based interventions but also clearly understand their nature, purpose, benefits, limitations, and potential risks. When AI systems operate without sufficient explanation or with technical complexity that is difficult for users to comprehend, there is a risk of undermining individual autonomy and turning treatment decisions into a vague and uncontrollable process. Upholding this principle, in addition to respecting human dignity and worth, forms the foundation of trust and effective collaboration among patients, clinicians, and technology. Genuine consent is achieved only when individuals have a clear understanding of what they accept, and their choices result from awareness and free will rather than mere implicit acceptance of machine recommendations. The findings of this section are in alignment with those reported in studies [16, 18-25, 32-34, 38, 47, 50, 52].

Professional responsibility and ethical practice

In the field of AI, professional practice and ethical responsibility refer to the commitment of specialists, developers, and technology users to adhere to professional ethical standards, norms, and values. This commitment encompasses ensuring accuracy, safety, transparency, and accountability throughout all stages of designing, implementing, and deploying AI systems. In healthcare, this principle requires that professionals not only understand the technical functions and limitations of AI models but also accept responsibility for the consequences of decisions based on this technology. Negligence in this regard can lead to diagnostic errors, patient harm, or erosion of public trust. Ethical professional practice serves as a bridge between technical capability and human responsibility, ensuring that technological innovation remains dedicated to the welfare and rights of stakeholders, rather than merely focusing on efficiency or processing speed. The findings of this section are consistent with those presented in studies [16-20, 22-25, 35, 48].

Clinical reliability and patient safety

In the context of AI within healthcare systems, treatment and clinical reliability refer to the capability of a system to provide accurate, consistent, and evidence-based therapeutic recommendations and support. This principle implies that AI outputs should not only be technically valid but also demonstrate reliable and reproducible performance across diverse clinical scenarios and patient populations. Clinical reliability requires continuous evaluation, validation with real-world data, and monitoring of treatment outcomes to ensure that the technology contributes to improved patient results and reduces medical errors. Ultimately, clinical reliability serves as a critical link between algorithmic innovation and patient safety, ensuring that therapeutic decisions are based on valid data and precise analyses rather than solely on automated predictions. The findings of this section converge with those reported in studies [16, 17, 19, 22, 23, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 43-45, 47, 48, 50, 52].

Legal, policy, and regulatory frameworks

In the realm of AI, legal, policy, and regulatory challenges play a crucial role in establishing safe, fair, and trustworthy frameworks for the development and deployment of these technologies. The rapid pace of AI advancement often outstrips the capacity of existing legal and regulatory mechanisms, resulting in legal gaps and unclear accountability. In healthcare, these gaps can have serious consequences, including a lack of clarity regarding liability in cases of errors or harm, an absence of standardized protocols for safety and efficacy assessment, and weak protection of sensitive patient data. Furthermore, conflicts of interest among developers, service providers, and policymakers may undermine the formulation of comprehensive and inclusive regulations. Therefore, creating flexible, transparent, and technology-aligned legal frameworks, alongside active involvement of diverse stakeholders, is essential to ensure the ethical and responsible use of AI in healthcare. The findings of this section align with those reported in studies [16, 20-30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41-45, 47, 49-51].

Challenges

The following is an analysis and explanation of each of these main ethical challenges.

Challenges related to data privacy and security

Given the extensive data requirements associated with the application of AI technologies in the healthcare sector, the preservation of patient privacy has emerged as one of the fundamental challenges in this domain. Although data encryption has been proposed as a means to mitigate security risks, the complexity of such methods may reduce the transparency of algorithmic operations, thereby potentially undermining patient trust in the healthcare system. Safeguarding patient information presents a major concern in the application of AI technologies within medical settings. The necessity of utilizing extensive datasets to train these systems raises the risk of compromising individuals’ private health records. While strategies, such as data encryption have been introduced to mitigate these risks, they often reduce the system’s interpretability, as complex security protocols can obscure algorithmic processes. This lack of clarity in data handling may erode trust between patients and healthcare providers, potentially discouraging open communication due to fears over confidentiality breaches [68]. Pervasive monitoring technologies in users’ environments result in significant privacy intrusions and turn the home into a medicalized space, which may cause psychological distress. At the same time, data-driven systems require vast amounts of information, often collected without clear user awareness or control. Users may struggle to understand who accesses their data and for what purpose, especially given the potential for indefinite storage. Compared to traditional in-person care, the risk of data leakage or loss is substantially higher [69].

Challenges related to transparency and explainability

The lack of transparency in AI systems goes beyond a technical shortcoming and is also an epistemic and ethical crisis within modern medicine. This is due to the delegation of decision-making processes to mechanisms that lie beyond human comprehension, thereby rendering accountability ambiguous. The inability to fully understand or interpret the outcomes generated by such systems poses significant challenges to defining and scaling professional ethical standards. This opacity is manifested in three semantic dimensions: lack of disclosure (where individuals are unaware that automated decisions are being made about them), epistemic opacity (when there is no access to or understanding of how decisions are made), and explanatory opacity (the inability to explain why a specific output is generated). Such opacity can hinder individuals from exercising data-related rights and weaken the trust between patients and physicians. Moreover, AI systems may rely on features that are unfamiliar or irrelevant to clinicians, with no clear scientific explanation for their association with clinical outcomes [70]. AI models, particularly deep learning systems, are often described as “black boxes” and epistemically opaque, meaning their internal decision-making processes are not transparent, even to experts. This poses a serious ethical challenge, as critical medical decisions are made by systems whose reasoning cannot be fully understood or explained. Such opacity directly conflicts with core principles of medical ethics, especially the patient’s right to informed consent, which requires clear information about the logic, significance, and potential consequences of diagnostic or therapeutic interventions [71].

Challenges related to fairness and algorithmic discrimination

The issue of fairness in AI is not merely a technical flaw, but rather a reflection of unjust human structures that are reproduced, and even amplified, through algorithmic systems. Despite their seemingly neutral design, medical algorithms are often built upon datasets that may be rooted in historical, social, and racial biases. Consequently, the emergence of injustice within these systems is not only possible but also probable. The issue of fairness in the use of AI systems arises primarily from unintended algorithmic biases and inherent statistical distortions embedded in the design and functioning of these technologies. These biases, often subtle yet deeply rooted, can lead to significant consequences across various domains, including healthcare, law, and social systems [72]. AI algorithms are only as reliable as the data they are built and are not entirely autonomous, as they reflect human-designed logic. Human errors and biases can be amplified through these systems, especially when applied to large datasets. Moreover, the homogeneity of input data often leads to the under- or over-representation of certain population groups, potentially reinforcing existing health disparities [73].

Challenges related to autonomy and informed consent

The reliance of AI on personal health data and information derived from social networks for decision-making in situations where individuals lack decision-making capacity is based on the assumption that one’s digital identity accurately reflects their real-world preferences. However, this assumption is highly contentious. Given the dynamic nature of human values and preferences, decisions made on the basis of past behaviors and online presence may lead to a misrepresentation of an individual’s current wishes. Data from personal health records and social media can be used by AI to support medical decision-making when an individual is incapacitated and no human surrogate is available. However, human preferences are dynamic, and it is uncertain whether a competent individual would consent to AI-generated decisions based on inferred online behavior. Social media identities often do not reflect genuine personal values, and AI systems may prioritize cost-efficiency over individual well-being. This raises ethical concerns, especially when surrogate decision-makers are present but potentially overruled by AI due to automation bias. Ultimately, this creates a tension between human-centered care and algorithm-driven efficiency [74]. Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon [75] warn that commercial providers of therapeutic AI may, under the guise of promoting patient autonomy, lead to therapeutic misconception, where users fail to accurately understand the system’s capabilities and limitations.

Challenges within professional practice and the obligations of ethical responsibility

The generative and creative nature of these models renders them prone to “hallucination”, the production of inaccurate or fabricated information, a characteristic that, in contexts such as healthcare, goes beyond an error but is a potential threat to human life. Physicians’ concerns about disruptions to clinical workflows caused by the integration of AI reflect an inherent tension between technological determinism and the preservation of coherence within experience- and evidence-based healthcare systems. It is important to note that large language models (LLMs) have not yet been approved for diagnostic or therapeutic use. These models, originally designed for creative tasks, are inherently prone to generating inaccurate information (hallucinations) and exhibiting bias. This means there is no official assurance that they meet the safety and efficacy standards required for clinical applications [76]. The integration of AI into clinical workflows has also introduced tension. Investigators conducting randomized controlled trials aimed to assess the effectiveness of AI without compromising patient safety or disrupting established care pathways with proven outcomes. Clinicians expressed concerns that modifying existing workflows to accommodate AI systems might unintentionally impact the quality of patient care or increase the workload for healthcare staff [77]. AI’s ability to analyze large volumes of patient data enables the detection of hidden patterns, but it also carries the risk of overdiagnosis. This involves identifying conditions that would not have impacted the patient’s health if left undetected. The consequences may include unnecessary treatments, potential harm to patients, and the misuse of healthcare resources [78].

Challenges related to treatment and clinical reliability

The growing role of AI tools in medical diagnostics, while seemingly promising on the surface, carries the deeper risk of gradually eroding human clinical judgment. Clinical judgment arises from a synthesis of experience, human insight, and direct patient interaction, elements that no algorithm has yet been able to fully replicate. Excessive reliance on machine-generated outputs may lead to a form of “cognitive surrender,” wherein the physician assumes the role of a passive validator of algorithmic suggestions rather than engaging in critical analysis. Although AI models demonstrate high accuracy, excessive reliance on machine-generated outputs may diminish the role of human expertise in medical decision-making. This is particularly troubling in complex cases that require a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s clinical condition, comorbidities, and personal preferences [79].

Legal, policy, and regulatory challenges

Policies, regulatory frameworks, and governance mechanisms related to AI also play a decisive role in shaping its ethical implications. A notable gap currently exists between existing legal structures and the rapid pace of technological advancements in this domain. Conflicting interests often emerge between those who develop and manage AI models and the goals of public health, particularly when viewed through the lens of government accountability and the inclusion of key stakeholders such as physicians and patients. One of the frequently raised concerns in AI-driven healthcare is the ambiguity surrounding accountability in the event of diagnostic or treatment errors. The technical complexity of AI systems, coupled with their proprietary nature, limits transparency, public scrutiny, and legal recourse. While some sources argue that healthcare professionals should be held responsible for AI-assisted decisions, others emphasize the responsibility of developers to ensure the safety, effectiveness, and suitability of AI systems for diverse patient populations [65]. The discourse on responsible surveillance and the preference for proactive over reactive regulatory approaches highlights the need for ethical frameworks to reduce public distrust and enable the ethical use of AI surveillance technologies in public health. The intersection of public and private sector surveillance further complicates data privacy and ethical use; as private companies often adhere to lower ethical standards than governmental bodies. Moreover, health-related data generated outside clinical settings typically fall outside the scope of privacy regulations. This regulatory gap allows commercial data collectors to legally aggregate individuals’ behavioral and social data from various sources for health and non-health purposes [80]. With the rapid expansion of AI in the healthcare sector, a significant regulatory gap has become increasingly evident. There is currently no clearly defined regulatory body, no standardized trial procedures, and no transparent accountability mechanisms in place to address potential harms caused by AI. This situation, often referred to as a “regulatory vacuum,” is particularly concerning in the context of legal responsibility for AI-driven decisions. While data protection regulations, such as the GDPR in the European :union: and HIPAA in the United States, are in effect, a comprehensive framework governing the clinical application of AI remains absent [81, 82, 83].

Conclusion

AI has brought about transformative advancements across multiple dimensions of the higher education and healthcare sectors. This meta-synthesis of 53 qualitative and review studies provides a comprehensive and multidimensional understanding of the ethical challenges posed by the integration of AI in healthcare. The analysis identified seven overarching themes: (a) data privacy, security, and ownership; (b) transparency and explainability; (c) algorithmic fairness and discrimination; (d) autonomy and informed consent; (e) professional responsibility and ethical engagement; (f) clinical reliability and trust in care; and (g) legal, regulatory, and governance challenges. These findings reveal that ethical concerns surrounding AI in healthcare are not limited to isolated technical issues but are deeply rooted in structural, epistemological, and socio-political dimensions. Across the themes, recurring patterns of asymmetry between patients and systems, humans and algorithms, low- and high-resource settings, highlight the potential for AI to reinforce existing inequities if left unchecked. The implications of this review are clear: ethically sound AI deployment requires more than robust technical design. It demands interdisciplinary collaboration, inclusive policymaking, critical engagement with power dynamics in data practices, and a commitment to protecting human dignity and agency. By offering an integrative thematic framework, this study provides a conceptual foundation for future empirical research and the development. Given the variety and complexity of ethical challenges identified in the use of AI in healthcare, such as data privacy, algorithmic transparency, bias and discrimination, patient autonomy, unclear responsibility, legal gaps, and concerns over clinical reliability, there is a strong need for further interdisciplinary and context-sensitive research. Future studies are encouraged to explore the real-world experiences of healthcare professionals, patients, and AI developers when interacting with AI-based systems in clinical settings. Qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews, ethnographic observation, and thematic analysis, can help reveal the practical and ethical tensions that may not be fully captured in theoretical models. Moreover, researchers should aim to develop localized ethical frameworks for the design and implementation of AI in healthcare. These frameworks should be co-created with key stakeholders, including policymakers, clinicians, and technology developers, to ensure practical relevance and cultural sensitivity. Finally, comparative research across countries with different levels of AI adoption in healthcare can provide insights into how cultural, institutional, and legal factors shape ethical challenges and solutions. Such work can contribute to a more comprehensive and globally informed understanding of trustworthy AI in health systems.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi, Supervision: Ahmad Keykha, Methodology and Data collection: Ahmad Keykha, Ava Taghavi and Jafar Shahrokhi, Investigation: Ahmad Keykha and Ava Taghavi; Writing the original draft Ahmad Keykha and Maryam Hojati Review & editing: Ava Taghavi; Data analysis: Ahmad Keykha and Maryam Hojati and Jafar Shahrokhi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the colleagues who contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the qualitative findings in this study. Their valuable insights and collaborative efforts were instrumental in enriching the research process.

References

Artificial intelligence (AI) has created unprecedented opportunities across diverse sectors, with particularly transformative impacts in medicine, healthcare education, and biomedical research. From personalized treatment recommendations and predictive diagnostics to intelligent tutoring systems and robotic-assisted surgeries, AI has rapidly evolved from a novel technological tool to a central component of contemporary medical ecosystems [1–4]. These developments promise increased efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility in clinical services and educational platforms alike.

However, the swift integration of AI into healthcare systems has simultaneously raised substantial ethical concerns. These include, but are not limited to, challenges related to algorithmic bias, the opacity of decision-making processes (“black-box” models), data privacy violations, the erosion of professional autonomy, legal ambiguities regarding responsibility and liability, and the risk of deskilling among healthcare practitioners [5–8]. For instance, when AI is used to augment or replace clinical decision-making, there is a growing fear that health professionals may lose core competencies over time and become overly reliant on algorithmic tools, thus compromising the development of sound clinical judgment and reducing physician-patient trust [9, 10].

Moreover, AI-generated content, whether in research or clinical documentation, raises questions about authorship, intellectual property rights, and the blurring boundaries between human and machine-generated outputs. These concerns are compounded by global disparities in access to AI technologies and the risk that such tools may exacerbate existing health inequities if not carefully monitored and ethically deployed.

Although there is a growing body of scholarship discussing the ethical implications of AI in medicine, a significant gap remains in terms of synthesizing qualitative insights from diverse empirical and review studies. Most existing analyses tend to focus on specific ethical domains (e.g. data protection or transparency), while neglecting the interconnectedness and complexity of ethical issues across real-world healthcare settings. Furthermore, few studies have systematically integrated qualitative findings from multiple perspectives—including patients, clinicians, developers, and ethicists—through a rigorous interpretive synthesis.

Given the ethical weight and social ramifications of AI deployment in healthcare, a more comprehensive and methodologically grounded understanding of these challenges is urgently needed. This study addressed this gap by conducting a qualitative meta-synthesis of peer-reviewed research, guided by the principles of thematic synthesis and informed by the PRISMA framework. Our objective was to identify the ethical challenges associated with the implementation of AI in healthcare. By consolidating diverse qualitative evidence into a coherent analytical framework, this study aimed to strengthen the theoretical and practical foundations for ethical AI governance in health systems.

Methods

We conducted a thematic synthesis of qualitative and review studies in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. We included qualitative and review studies that focused on the ethical challenges associated with the application of AI in healthcare. Study appraisal involved the use of a validated quality assessment tool [11]. Thematic synthesis techniques [12] were employed for analysis and synthesis, and the GRADE-CERQual approach [13] was applied to assess the confidence in the review findings.

Criteria for inclusion

A comprehensive and systematic search strategy was developed in consultation with an academic librarian. Searches were performed across four major electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Each search included combinations of controlled vocabulary (e.g. MeSH terms) and free-text keywords related to AI, ethics, and healthcare, alongside filters for qualitative and review studies. The search strategy for each database was tailored to its syntax and structure. Searches were conducted between May 15, 2010, and 2015.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify relevant studies across major academic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search combined controlled vocabulary terms and free-text keywords related to AI, ethics, and healthcare. Specifically, the following search terms were used: (“AI” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “AI”) AND (“ethics” OR “ethical issues” OR “ethical challenges” OR “ethical considerations” OR “bioethics”) AND (“healthcare” OR “health care” OR “medicine” OR “clinical practice” OR “medical ethics”) AND (“qualitative study” OR “qualitative research” OR “systematic review” OR “narrative review” OR “thematic synthesis”).

Study selection

All retrieved records were organized using Microsoft Excel, where duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening was conducted by two independent reviewers (Ahmad Keykha and Ava Taghavi Monfared) in duplicate for an initial subset of articles to ensure consistency in applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. The remaining articles were then equally divided and screened individually. Full-text assessments were conducted independently by the same two reviewers, and disagreements were resolved through consensus with input from a third reviewer (Jafar Shahrokhi and Maryam Hojati) when needed. During the study selection process, all retrieved records were imported into Microsoft Excel. After removing duplicates and retracted articles (n=10), titles (n=89) and abstracts (n=56) were screened. This resulted in 78 articles for full-text review. These reasons are reflected in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

To assess the methodological rigor of included studies, we employed the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) qualitative checklist [14], which includes ten standard questions evaluating aspects, such as study design, data collection, ethical considerations, and validity of findings. Each question was scored as either “yes”=10, “no”=0, or “can’t tell”=5. thus, the maximum possible score for each study was 100. No differential weighting was applied to individual items. The “Total” score represents the cumulative sum of the ten individual question scores. Studies scoring (below 50) were considered methodologically weak and were excluded from the final thematic synthesis. However, they are reported for transparency and completeness. The quality appraisal was conducted independently by two reviewers (Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi), and disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (Maryam Hojati) (Appendix 1).

Risk of bias assessment

To evaluate the risk of bias in the included studies, we employed the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for qualitative and review studies, supplemented by the ROBIS framework [15] for systematic reviews. The assessment focused on key domains, including study selection, data collection methods, clarity of ethical considerations, transparency in reporting, and potential conflicts of interest. Each study was independently assessed by two reviewers (Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi), with discrepancies resolved by consensus or by consultation with a third reviewer (Maryam Hojati). The results of the risk of bias assessment are summarized in Figure 2, using a traffic-light system (green=low risk, yellow=unclear risk, red=high risk). This visual representation provides a transparent overview of the methodological soundness and credibility of the included studies.

Data extraction and analysis

The analysis was guided by the core principles of thematic synthesis [12]. Data extraction and thematic development were performed by two researchers (Ahmad Keykha and Jafar Shahrokhi) working in parallel. Themes were developed inductively following the principles of thematic synthesis, rather than based on an a priori framework. The key findings and themes reported in this index paper were systematically coded and organized within a spreadsheet, forming the basis of an initial thematic framework. As subsequent studies were reviewed, their findings were coded and integrated into this evolving framework, which was refined iteratively as new data were incorporated. The analysis involved identifying patterns across studies, while also actively seeking out contradictory or disconfirming data—evidence that challenged either the emerging themes or the reviewers’ prior assumptions. This step was essential in ensuring the robustness of the synthesis. Data extraction and thematic development occurred in parallel.

Data validation

To ensure the reliability of the extracted concepts, the primary researcher compared their interpretations with those of an expert in the field. Inter-rater agreement was then assessed using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, yielding a value of k=0.664, with a significance level of P=0.001. According to the interpretation guidelines provided by Jensen and Allen [54], this level of agreement is considered acceptable, indicating substantial consistency between raters.

Results

The inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in this review were predefined according to the PICOS framework, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the results of the content analysis of the reviewed articles.

The process involved initially extracting key codes or concepts. These codes were then categorized into sub-themes based on their similarities and differences. Subsequently, the sub-themes were grouped into main themes through a similar comparative analysis. Table 2 comprises six main themes, each further divided into sub-themes based on topical similarity. For each main theme and its corresponding sub-themes, the key concepts constituting that theme are presented, accompanied by reference numbers indicating the supporting sources.

The content analysis revealed that the most frequently addressed theme, cited in over 35 studies, concerns challenges related to data privacy and security, underscoring a widespread concern regarding the control, ownership, and protection of health data in AI-based platforms. AI systems need large amounts of sensitive information to make decisions, such as medical history, genetic data, or mental health records. However, it is often unclear how this data is collected, stored, or used. Without proper safeguards, data may be misused or leaked. If patients do not trust the safety of their data, they may reject the use of AI in healthcare settings.

Closely following this are transparency and explainability challenges, highlighted in over 32 studies, particularly focusing on the “black box” nature of algorithms and the lack of standardized validation protocols for algorithms, especially those based on deep learning, which often work like a “black box,” meaning users cannot understand how the system makes decisions. This lack of transparency makes it difficult for doctors to explain AI-based diagnoses or treatment recommendations to patients. When decisions are not clearly explained, both medical professionals and patients may lose trust in the system. Improving explainability is essential for the responsible and accepted use of AI in medicine.

Issues of fairness and algorithmic discrimination were found in approximately 28 studies, with emphasis on biased datasets and the exclusion of marginalized populations. AI systems can unintentionally act in unfair or biased ways toward certain social or ethnic groups. This usually happens when the training data is not diverse enough. For example, the algorithm may work well for young men but perform poorly for women, the elderly, or minority populations. Such biases can lead to unequal access to quality care and may even worsen existing health disparities. Ensuring fairness requires using inclusive, representative datasets.

Autonomy and informed consent challenges were identified in 25 studies, raising alarms about the diminishing decision-making power of patients and physicians. The growing use of AI in healthcare can limit the decision-making power of both doctors and patients. In many cases, the system recommends without explaining the process, and the patient may feel forced to accept it. This can reduce the patient’s ability to make informed and independent choices. Respecting patient autonomy means ensuring that patients understand the AI’s role and have real options in their care decisions.

Ethical concerns tied to professional responsibility emerged in 22 studies. The use of AI in clinical environments raises questions about who is responsible when something goes wrong. If an AI system makes a harmful mistake, it is often unclear whether the doctor, the software developer, or the technology provider is accountable. This lack of clarity can reduce trust and make legal or ethical follow-up difficult. Clear rules are needed to define responsibility and ensure accountability in AI-assisted medical decisions.

Legal and regulatory gaps and clinical reliability issues were addressed in around 20 and 18 studies, respectively. Many countries still lack clear legal frameworks for regulating the use of AI in healthcare. There are few standards for evaluating the safety, effectiveness, or transparency of these systems. As a result, some technologies are used without proper oversight, increasing the risk of harm. Policymakers must create strong, future-oriented regulations that address the unique challenges of AI in medicine. AI systems that perform well in laboratory settings may not work as reliably in real-world clinical environments. Factors such as poor data quality, patient diversity, or differences in local healthcare resources can affect performance. If the system is not carefully tested in real conditions, it may produce inaccurate or harmful results. Thorough validation in practical settings is essential before wide adoption in medical practice.

Table 3 summarizes the key ethical challenges identified in the reviewed literature, organized into six main themes.

Each theme is illustrated with a concise real-world or hypothetical case context to enhance practical relevance. For each case, Table 3 also outlines the associated policy or practice implications and provides a GRADE-CERQual confidence rating to indicate the strength of evidence and ethical severity. This structure enables readers to quickly grasp the nature of the challenge, its contextual manifestation, and its potential impact on healthcare systems.

The findings in Table 3 highlight the multi-dimensional nature of ethical challenges in AI-enabled healthcare, spanning privacy, transparency, fairness, autonomy, professional responsibility, clinical reliability, and regulatory governance. Data privacy and security risks underscore the urgent need for robust legal and technical safeguards, while transparency and explainability issues emphasize the necessity of mandatory disclosure and interpretability standards. Persistent algorithmic bias illustrates the deep-seated equity implications of AI, necessitating proactive dataset diversification and bias auditing. Challenges to autonomy reveal a pressing requirement for patient-centered consent processes that are both accessible and informative. Within professional practice, the absence of clear accountability mechanisms threatens ethical integrity, and in clinical contexts, reliability concerns demand rigorous validation and human oversight. Finally, the lack of harmonized legal frameworks not only undermines governance but also delays resolution in cases of harm. Collectively, these themes indicate that ethical AI integration in healthcare requires systemic, cross-disciplinary interventions that bridge technical, regulatory, and human-centered approaches.

Comparison with existing reviews

In the following section of the findings, a comparative analysis of this meta-synthesis article with existing review studies on the ethical challenges of AI in healthcare is presented. Subsequently, Table 4 provides a summary of the review articles in this field.

In contrast to the reviews presented in Table 4, which are mostly in the form of narrative reviews, systematic reviews, or scoping reviews and whose primary focus is on compiling, categorizing, and descriptively presenting the findings of previous studies, the present research adopted an analytical–synthetic approach through the use of meta-synthesis and qualitative content analysis. This approach, in addition to collecting secondary data, reconstructed them through a systematic process involving coding, categorization, synthesis, and in-depth interpretation. Accordingly, the present study not only identified the common themes and patterns among previous research but also uncovered the gaps, contradictions, and shortcomings in the literature, ultimately offering an integrated analytical framework for a more comprehensive understanding of the ethical challenges of AI in healthcare. Therefore, while prior reviews mainly address the question of “what findings have been reported,” this meta-synthesis examined “how these findings interrelate, what conceptual connections exist among them, and what new pathways can be outlined for future research and policy-making.”

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the ethical challenges of AI in healthcare. To achieve this objective, a content analysis was conducted on selected qualitative and review studies. In total, seven main themes and thirty-three sub-themes were identified. Figure 3 is a schematic model of the research findings.

Data privacy and security as the cornerstone of trust

In the field of AI, data privacy and security are not merely technical requirements but form the foundation of trust and stability in intelligent ecosystems. The quality and diversity of data, which underpin the learning and accuracy of algorithms, are meaningful only when users are confident that their information is stored and processed in a secure and controlled environment. This issue is especially critical in healthcare, where medical data reflect not only individuals’ physical conditions but also their psychological, social, and even genetic dimensions. Protecting this data directly influences technology acceptance, voluntary participation in innovative projects, and ultimately the pace of scientific advancement. In other words, data security in AI serves as a bridge linking innovation to public trust, and without it, even the most advanced algorithms will face distrust and social resistance. The findings of this section align with those reported in case studies [16, 18, 21-27, 30-33, 35, 37-41, 43-49, 51].

Transparency and explainability for accountability

In the field of AI, transparency and explainability constitute the backbone of trust, accountability, and social acceptance of the technology. Algorithms whose decision-making processes can be explained at a human-understandable level enable effective oversight, evaluation, and correction, preventing intelligent systems from becoming “black boxes.” This principle is especially critical in healthcare, where algorithmic decisions can directly impact patients’ lives and quality of care. When both clinicians and patients can comprehend the rationale behind a diagnosis or treatment recommendation, truly informed consent becomes possible, and accountability is strengthened at individual and institutional levels. Moreover, transparency and explainability not only serve as tools to detect errors and biases but also create a foundation for continuous learning and improvement of algorithms, fostering a constructive and trustworthy interaction between medical science and AI technology. The findings of this section align with those reported in studies [16, 21, 25, 26, 28-34, 37, 38, 41, 43, 44, 49-51].

Fairness and mitigation of algorithmic bias

In the realm of AI, fairness and algorithmic discrimination are intrinsically linked to social justice, equitable access to services, and the ethical legitimacy of technology. Algorithms reflect the data on which they are trained; therefore, if these datasets contain historical, social, or structural biases, intelligent systems may unintentionally reproduce and even amplify existing inequalities. In healthcare, this issue carries critical implications, from diagnostic errors in underrepresented population groups to inequitable allocation of treatment resources. Ensuring fairness in algorithms is not only an ethical imperative but also a prerequisite for public trust and clinical efficacy. Consequently, continuous monitoring, responsible data-driven design, and evaluation of social impacts are integral components of developing and deploying fair AI systems. The findings of this section are consistent with those presented in studies [16, 18, 20-24, 26, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 38, 42-44, 45, 46, 49-52].

Autonomy and informed consent in clinical practice

In the context of AI, autonomy and informed consent refer to preserving individuals’ right to make free decisions based on complete and transparent information. In medical applications, this principle ensures that patients are not only aware of AI-based interventions but also clearly understand their nature, purpose, benefits, limitations, and potential risks. When AI systems operate without sufficient explanation or with technical complexity that is difficult for users to comprehend, there is a risk of undermining individual autonomy and turning treatment decisions into a vague and uncontrollable process. Upholding this principle, in addition to respecting human dignity and worth, forms the foundation of trust and effective collaboration among patients, clinicians, and technology. Genuine consent is achieved only when individuals have a clear understanding of what they accept, and their choices result from awareness and free will rather than mere implicit acceptance of machine recommendations. The findings of this section are in alignment with those reported in studies [16, 18-25, 32-34, 38, 47, 50, 52].

Professional responsibility and ethical practice

In the field of AI, professional practice and ethical responsibility refer to the commitment of specialists, developers, and technology users to adhere to professional ethical standards, norms, and values. This commitment encompasses ensuring accuracy, safety, transparency, and accountability throughout all stages of designing, implementing, and deploying AI systems. In healthcare, this principle requires that professionals not only understand the technical functions and limitations of AI models but also accept responsibility for the consequences of decisions based on this technology. Negligence in this regard can lead to diagnostic errors, patient harm, or erosion of public trust. Ethical professional practice serves as a bridge between technical capability and human responsibility, ensuring that technological innovation remains dedicated to the welfare and rights of stakeholders, rather than merely focusing on efficiency or processing speed. The findings of this section are consistent with those presented in studies [16-20, 22-25, 35, 48].

Clinical reliability and patient safety

In the context of AI within healthcare systems, treatment and clinical reliability refer to the capability of a system to provide accurate, consistent, and evidence-based therapeutic recommendations and support. This principle implies that AI outputs should not only be technically valid but also demonstrate reliable and reproducible performance across diverse clinical scenarios and patient populations. Clinical reliability requires continuous evaluation, validation with real-world data, and monitoring of treatment outcomes to ensure that the technology contributes to improved patient results and reduces medical errors. Ultimately, clinical reliability serves as a critical link between algorithmic innovation and patient safety, ensuring that therapeutic decisions are based on valid data and precise analyses rather than solely on automated predictions. The findings of this section converge with those reported in studies [16, 17, 19, 22, 23, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 43-45, 47, 48, 50, 52].

Legal, policy, and regulatory frameworks

In the realm of AI, legal, policy, and regulatory challenges play a crucial role in establishing safe, fair, and trustworthy frameworks for the development and deployment of these technologies. The rapid pace of AI advancement often outstrips the capacity of existing legal and regulatory mechanisms, resulting in legal gaps and unclear accountability. In healthcare, these gaps can have serious consequences, including a lack of clarity regarding liability in cases of errors or harm, an absence of standardized protocols for safety and efficacy assessment, and weak protection of sensitive patient data. Furthermore, conflicts of interest among developers, service providers, and policymakers may undermine the formulation of comprehensive and inclusive regulations. Therefore, creating flexible, transparent, and technology-aligned legal frameworks, alongside active involvement of diverse stakeholders, is essential to ensure the ethical and responsible use of AI in healthcare. The findings of this section align with those reported in studies [16, 20-30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41-45, 47, 49-51].

Challenges

The following is an analysis and explanation of each of these main ethical challenges.

Challenges related to data privacy and security

Given the extensive data requirements associated with the application of AI technologies in the healthcare sector, the preservation of patient privacy has emerged as one of the fundamental challenges in this domain. Although data encryption has been proposed as a means to mitigate security risks, the complexity of such methods may reduce the transparency of algorithmic operations, thereby potentially undermining patient trust in the healthcare system. Safeguarding patient information presents a major concern in the application of AI technologies within medical settings. The necessity of utilizing extensive datasets to train these systems raises the risk of compromising individuals’ private health records. While strategies, such as data encryption have been introduced to mitigate these risks, they often reduce the system’s interpretability, as complex security protocols can obscure algorithmic processes. This lack of clarity in data handling may erode trust between patients and healthcare providers, potentially discouraging open communication due to fears over confidentiality breaches [68]. Pervasive monitoring technologies in users’ environments result in significant privacy intrusions and turn the home into a medicalized space, which may cause psychological distress. At the same time, data-driven systems require vast amounts of information, often collected without clear user awareness or control. Users may struggle to understand who accesses their data and for what purpose, especially given the potential for indefinite storage. Compared to traditional in-person care, the risk of data leakage or loss is substantially higher [69].

Challenges related to transparency and explainability

The lack of transparency in AI systems goes beyond a technical shortcoming and is also an epistemic and ethical crisis within modern medicine. This is due to the delegation of decision-making processes to mechanisms that lie beyond human comprehension, thereby rendering accountability ambiguous. The inability to fully understand or interpret the outcomes generated by such systems poses significant challenges to defining and scaling professional ethical standards. This opacity is manifested in three semantic dimensions: lack of disclosure (where individuals are unaware that automated decisions are being made about them), epistemic opacity (when there is no access to or understanding of how decisions are made), and explanatory opacity (the inability to explain why a specific output is generated). Such opacity can hinder individuals from exercising data-related rights and weaken the trust between patients and physicians. Moreover, AI systems may rely on features that are unfamiliar or irrelevant to clinicians, with no clear scientific explanation for their association with clinical outcomes [70]. AI models, particularly deep learning systems, are often described as “black boxes” and epistemically opaque, meaning their internal decision-making processes are not transparent, even to experts. This poses a serious ethical challenge, as critical medical decisions are made by systems whose reasoning cannot be fully understood or explained. Such opacity directly conflicts with core principles of medical ethics, especially the patient’s right to informed consent, which requires clear information about the logic, significance, and potential consequences of diagnostic or therapeutic interventions [71].

Challenges related to fairness and algorithmic discrimination

The issue of fairness in AI is not merely a technical flaw, but rather a reflection of unjust human structures that are reproduced, and even amplified, through algorithmic systems. Despite their seemingly neutral design, medical algorithms are often built upon datasets that may be rooted in historical, social, and racial biases. Consequently, the emergence of injustice within these systems is not only possible but also probable. The issue of fairness in the use of AI systems arises primarily from unintended algorithmic biases and inherent statistical distortions embedded in the design and functioning of these technologies. These biases, often subtle yet deeply rooted, can lead to significant consequences across various domains, including healthcare, law, and social systems [72]. AI algorithms are only as reliable as the data they are built and are not entirely autonomous, as they reflect human-designed logic. Human errors and biases can be amplified through these systems, especially when applied to large datasets. Moreover, the homogeneity of input data often leads to the under- or over-representation of certain population groups, potentially reinforcing existing health disparities [73].

Challenges related to autonomy and informed consent

The reliance of AI on personal health data and information derived from social networks for decision-making in situations where individuals lack decision-making capacity is based on the assumption that one’s digital identity accurately reflects their real-world preferences. However, this assumption is highly contentious. Given the dynamic nature of human values and preferences, decisions made on the basis of past behaviors and online presence may lead to a misrepresentation of an individual’s current wishes. Data from personal health records and social media can be used by AI to support medical decision-making when an individual is incapacitated and no human surrogate is available. However, human preferences are dynamic, and it is uncertain whether a competent individual would consent to AI-generated decisions based on inferred online behavior. Social media identities often do not reflect genuine personal values, and AI systems may prioritize cost-efficiency over individual well-being. This raises ethical concerns, especially when surrogate decision-makers are present but potentially overruled by AI due to automation bias. Ultimately, this creates a tension between human-centered care and algorithm-driven efficiency [74]. Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon [75] warn that commercial providers of therapeutic AI may, under the guise of promoting patient autonomy, lead to therapeutic misconception, where users fail to accurately understand the system’s capabilities and limitations.

Challenges within professional practice and the obligations of ethical responsibility

The generative and creative nature of these models renders them prone to “hallucination”, the production of inaccurate or fabricated information, a characteristic that, in contexts such as healthcare, goes beyond an error but is a potential threat to human life. Physicians’ concerns about disruptions to clinical workflows caused by the integration of AI reflect an inherent tension between technological determinism and the preservation of coherence within experience- and evidence-based healthcare systems. It is important to note that large language models (LLMs) have not yet been approved for diagnostic or therapeutic use. These models, originally designed for creative tasks, are inherently prone to generating inaccurate information (hallucinations) and exhibiting bias. This means there is no official assurance that they meet the safety and efficacy standards required for clinical applications [76]. The integration of AI into clinical workflows has also introduced tension. Investigators conducting randomized controlled trials aimed to assess the effectiveness of AI without compromising patient safety or disrupting established care pathways with proven outcomes. Clinicians expressed concerns that modifying existing workflows to accommodate AI systems might unintentionally impact the quality of patient care or increase the workload for healthcare staff [77]. AI’s ability to analyze large volumes of patient data enables the detection of hidden patterns, but it also carries the risk of overdiagnosis. This involves identifying conditions that would not have impacted the patient’s health if left undetected. The consequences may include unnecessary treatments, potential harm to patients, and the misuse of healthcare resources [78].

Challenges related to treatment and clinical reliability

The growing role of AI tools in medical diagnostics, while seemingly promising on the surface, carries the deeper risk of gradually eroding human clinical judgment. Clinical judgment arises from a synthesis of experience, human insight, and direct patient interaction, elements that no algorithm has yet been able to fully replicate. Excessive reliance on machine-generated outputs may lead to a form of “cognitive surrender,” wherein the physician assumes the role of a passive validator of algorithmic suggestions rather than engaging in critical analysis. Although AI models demonstrate high accuracy, excessive reliance on machine-generated outputs may diminish the role of human expertise in medical decision-making. This is particularly troubling in complex cases that require a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s clinical condition, comorbidities, and personal preferences [79].

Legal, policy, and regulatory challenges