Volume 14, Issue 1 (Jan & Feb 2024)

J Research Health 2024, 14(1): 43-54 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Tiwari G K, Tiwari R P, Pandey R, Ray B, Dwivedi A, Sharma D N, et al . Perceived Life Outcomes of Indian Children During the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Protective Roles of Joint and Nuclear Families. J Research Health 2024; 14 (1) :43-54

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2357-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2357-en.html

Gyanesh Kumar Tiwari1

, Raghavendra Prasad Tiwari2

, Raghavendra Prasad Tiwari2

, Rakesh Pandey3

, Rakesh Pandey3

, Bablu Ray4

, Bablu Ray4

, Abhigyan Dwivedi4

, Abhigyan Dwivedi4

, Devaki Nandan Sharma5

, Devaki Nandan Sharma5

, Pankaj Singh6

, Pankaj Singh6

, Ajay Kumar Tiwari7

, Ajay Kumar Tiwari7

, Ajit Kumar Singh8

, Ajit Kumar Singh8

, Raghavendra Prasad Tiwari2

, Raghavendra Prasad Tiwari2

, Rakesh Pandey3

, Rakesh Pandey3

, Bablu Ray4

, Bablu Ray4

, Abhigyan Dwivedi4

, Abhigyan Dwivedi4

, Devaki Nandan Sharma5

, Devaki Nandan Sharma5

, Pankaj Singh6

, Pankaj Singh6

, Ajay Kumar Tiwari7

, Ajay Kumar Tiwari7

, Ajit Kumar Singh8

, Ajit Kumar Singh8

1- Department of Psychology, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India. , gyaneshpsychology@gmail.com

2- Vice-Chancellor, Central University of Punjab, Punjab, India.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

4- Department of Linguistics, School of Languages, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India.

5- Department of Psychology, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India.

6- Department of History, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India.

7- Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

8- Department of Psychology, Amity Institute of Behavioural & Allied Sciences, Amity University, Rajasthan, India.

2- Vice-Chancellor, Central University of Punjab, Punjab, India.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

4- Department of Linguistics, School of Languages, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India.

5- Department of Psychology, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India.

6- Department of History, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Dr Hari Singh Gour University, Sagar, India.

7- Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

8- Department of Psychology, Amity Institute of Behavioural & Allied Sciences, Amity University, Rajasthan, India.

Keywords: Children, COVID-19, Joint family, Perceived life outcomes, Nuclear family, Thematic analysis

Full-Text [PDF 671 kb]

(491 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (13916 Views)

Full-Text: (616 Views)

Introduction

Due to the unprecedented and unparalleled restrictions, fear, and uncertainty, the COVID-19 pandemic has created an indescribable situation of anguish and pain for all human beings. It has created severe distress, anxiety, uncertainty, and challenges to the life outcomes of children and adults [1, 2]. United Nations Organization (UN) has observed that children are one of the biggest sufferers of this pandemic and its negative influences may be significantly influenced by the economic and social conditions of families and their health conditions [3]. Children face acute unavailability of the needed resources, social support, and services, which exposes them to face psychological distress, violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation which, in turn, may adversely affect their development and well-being [4, 5].

A phone-based study of 144 families from Canada during April-May 2020 also revealed that parents and children showed family-related changes, health problems, and fears in children aged 9-12 years and their parents [6]. Research in India also observed that parents and families experienced a constant sense of loss of social networks, employment, financial security, and relatives which, in turn, may negatively impact the quality of relationships [7]. Given the dependence of 370 million children (0-14 years) in India on positive family processes for a variety of outcomes, their care during this period may be challenging due to social disruptions, gender norm changes, school closure, lack of extracurricular/outdoor activities, new eating and sleeping habits, lack of peer-relationships and boredom [7, 8]. These negative consequences for children may go beyond imagination since the current pandemic is more traumatic, pervasive, and uncertain [2, 9, 10].

The family acts as a crucial and universal agency that provides care for children. Various forms of families with different structures and functions are found. One typology is a joint family and a nuclear family. According to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary (2020), a joint family is a consanguineal unit that includes two or more generations of kindred related through either paternal or maternal line who maintain a common residence and are subject to common social, economic, and religious regulations [11]. A nuclear family refers to a group consisting only parents and children [12]. The joint family system is the major vehicle of collective values and practices, guided by shared identity, deep attachments, unique socialization, emotionality, meaning, relationships, concern for others, interdependence, and relatively permanent relationships [13–16]. In parallel, a nuclear family is based on individualistic values and lays emphasis on individual identity, independence, self-esteem, and personal achievements [13, 17].

Dissimilar life outcomes for children are associated with the two-family systems. For example, a joint family is more supportive of children to achieve psychological well-being than a nuclear family [18]. The differences in the outcomes of children of the two family systems have been assumed to be the results of dissimilarities in parent relations and social relations [19, 20], kin rivalry [21] and parental resources, the mental health of parents, parent-child relations, quality of relationships between parents and parental discrepancy [22, 23]. These differences facilitate the children of joint families to show better performance on the various components of psychological well-being, such as autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations, purpose in life, and self-acceptance compared to their nuclear family counterparts [18]. Besides, children from joint families show lower behavioral problems [24] and higher emotional maturity than children from nuclear families [25].

Joint families reflect a collectivistic culture [26], characterized by strong family bonds, positive environments, close monitoring, and promotion of family activities helping their children to safeguard from ill consequences in life [27]. They also emphasize interdependence, obedience, proper behaviour, social obligations, and group achievement [28]. Conversely, nuclear families represent an individualistic culture that emphasizes independence, individual rights, and self-sufficiency [29]. Thus, nuclear families nurture their children’s autonomy, self-interest, self-reliance, self-expression, and individual identity [28]. These two family systems provide different kinds of socialization opportunities and engagements for their children [30]. Due to the underexploration of the impacts of COVID-19 on children, it was necessitated to understand the underlying dynamics of the protective roles of joint and nuclear families in shaping their life outcomes during COVID-19.

Although the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are well-documented for the population, little research is conducted on its impacts on parents, families, and children [1, 31]. The distress of the recent pandemic has severely influenced the life outcomes of children similar to adults [1]. The study of children is also critical for other reasons. Families differ in providing care and support to their children. For example, a joint family may provide more live, long-term, and varied positive stimulations emanating from the dynamics of relationships among children, siblings, parents, grandparents, and other relatives. On the other hand, a nuclear family may become naturally restrictive and less live and short-term stimulating due to the limited size and restricted variety of relationships.

Recent research suggests that the recent pandemic opens up new avenues in social and cultural relationships along with inequality, distress, and discrimination [32]. These new opportunities can be effectively captured with qualitative studies since they provide reliable ways to capture, individual, group, and community responses as well as help to make sense of meaning, interactions, new insights, health, and illness. Instead of focusing on what, they help to understand why and how, they can also fill the gap between assumptions and realities and help to understand the social, cultural, and political aspects of a phenomenon [32]. Thus, in the present case, a qualitative method may also help to better understand the underlying processes and mechanisms of the impacts of the severe restrictions and quarantine during the COVID-19 lockdown.

The current study chose children aged 9 to 12 years since the children of this age group remain completely dependent on their parents and other family members for their satisfaction of needs and care to a large extent. Besides, these children can speak out their demands and show understandable emotional and behavioral responses. This makes their behavior comprehensive, stable, and patterned. Besides, these children also understand the necessity and compulsion of adherence to the restrictions of the lockdown. In this backdrop, the study aims to explore the perceived protective roles of joint and nuclear families in shaping the life outcomes of children aged 9 to 12 years, during the restrictions of the COVID-19 lockdown through a qualitative research design. The study results showed that COVID-19 is traumatic, pervasive, and uncertain and thus, it may leave negative marks on children’s development. Joint and nuclear families differ in their protective strengths for children in adversities, such as the recent pandemic. The two families vary in their positive engagements, emotional resources, and activity management methods for their children.

Methods

This study was conducted using a qualitative research design. A realist approach was used to understand and theorize the meaning, experience, and motivations inherent in the data in an uncomplicated way [33]. The study was conducted during June and July 2020 at Sagar City of Madhya Pradesh, India.

Participants

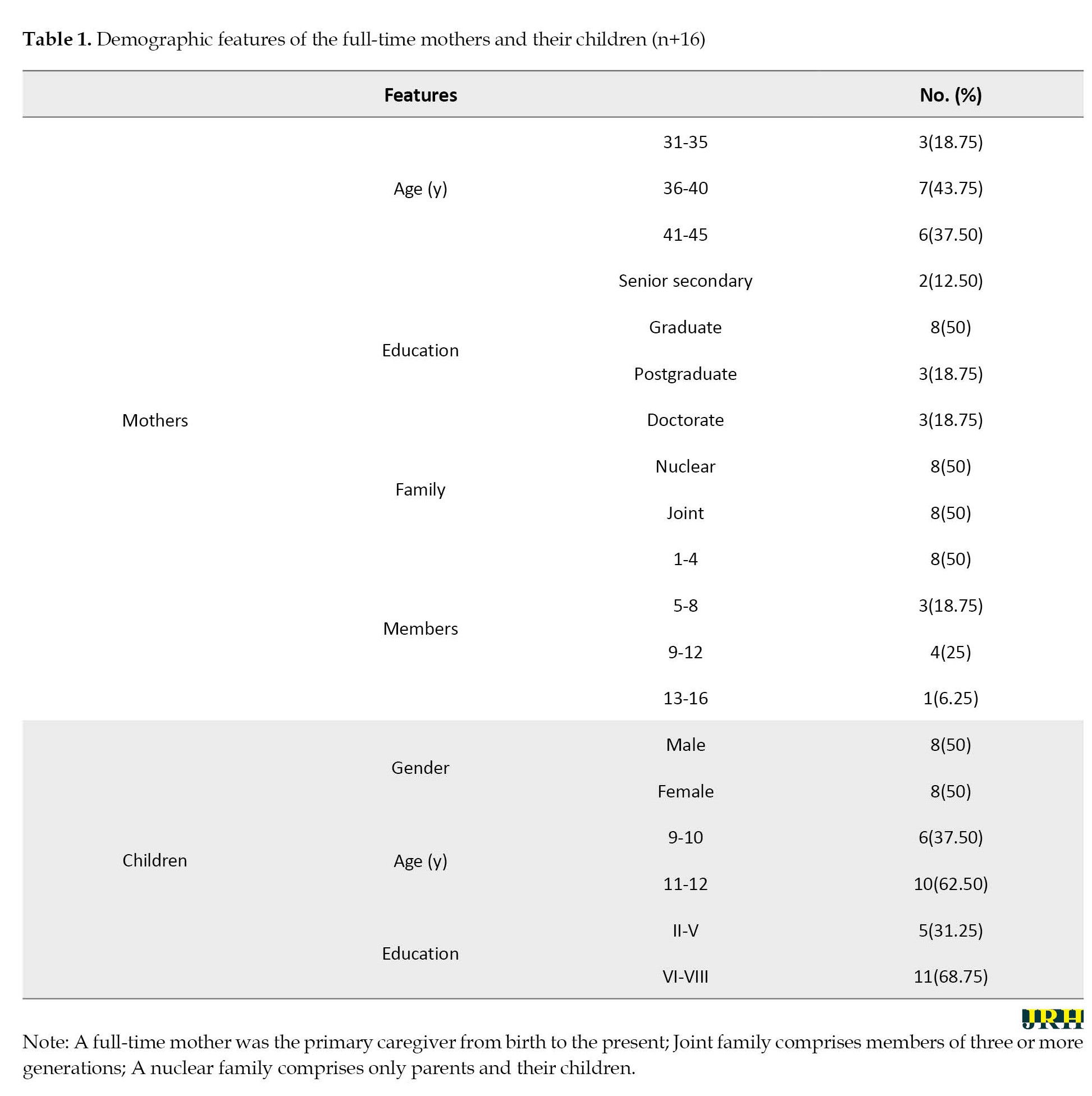

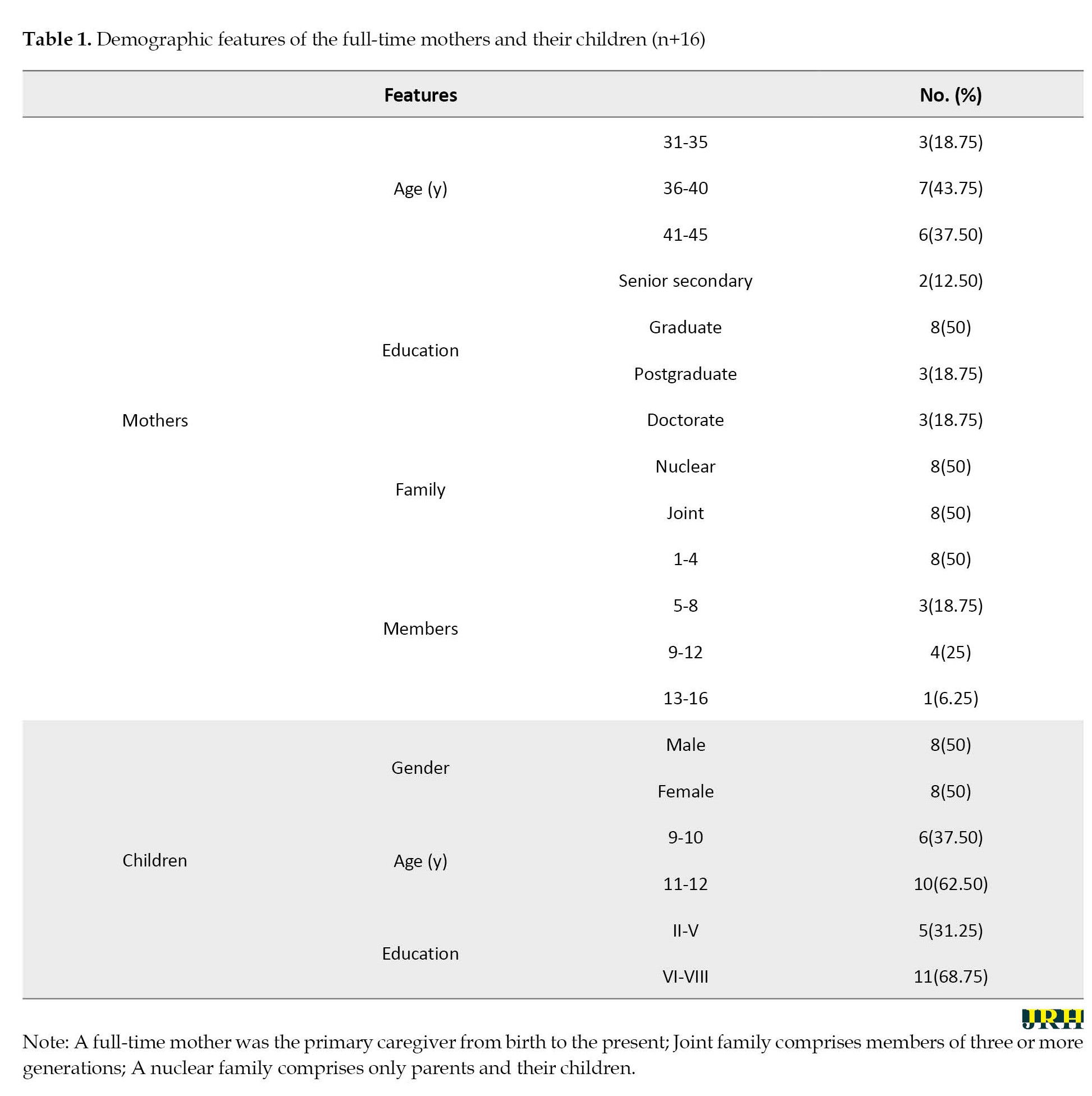

Sixteen full-time mothers (age range=33-45 years) were selected. Eight mothers were from joint families with Mean±SD of 41.63±2.62 and 8 mothers were from nuclear families with Mean±SD of 37.50±3.07. Their children’s age was from 9 to 12 years (Mean±SD, 10.66±1.17) (Table 1).

We chose only full-time mothers since they represent an information-rich group and were able to describe and reflect upon their children’s behaviors and experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown [34]. The selection of full-time mothers has been reported to be useful as a rich source of information regarding their children’s behaviors in the approximately current age group in some recent studies [2, 35].

The inclusion criteria included a full-time mother, affiliation with either a joint family or nuclear family, and a mother of at least one child with an age range from 9 to 12 years. The information about the study was circulated among the prospective participants through email, Facebook, and WhatsApp messages with full descriptions by the authors’ identifiers. Initially, 27 mothers gave their consent on the telephone, but 11 of them did not participate in the study due to their different personal reasons. Thus, 16 full-time mothers finally participated who belonged to sub-urban middle-class families and mostly adhered to the Hindu religion. Informed consent was obtained from all participants by telephone.

Data collection

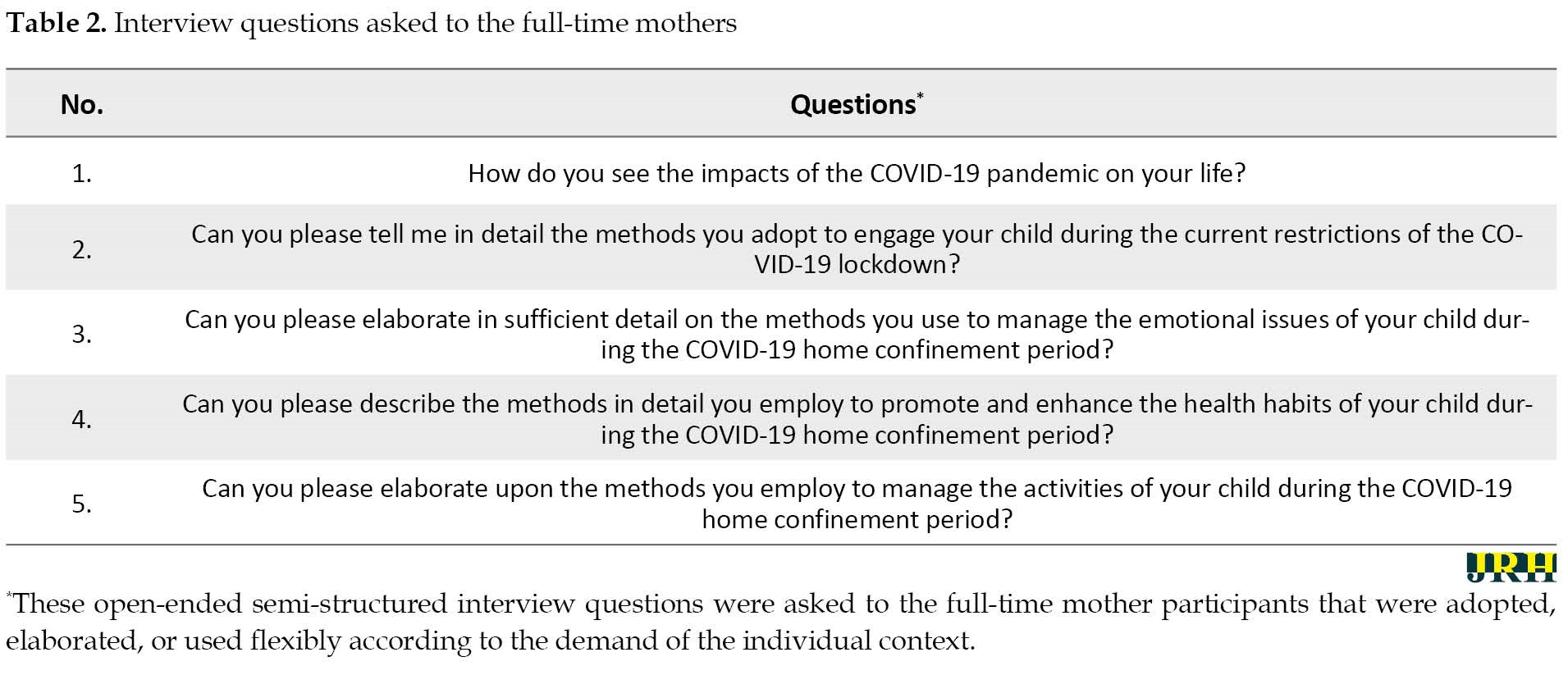

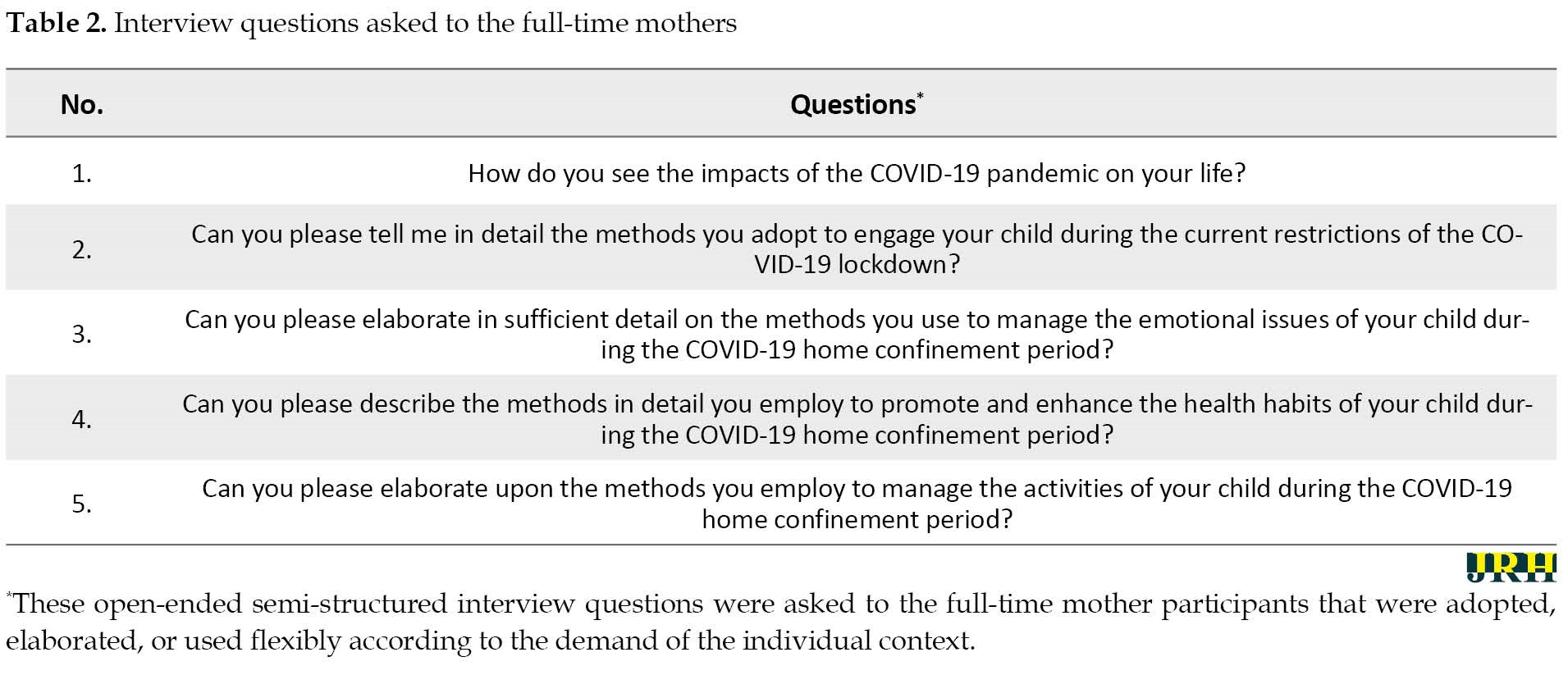

A quasi-structured interview protocol was used to collect the data through telephone calls. The structure of the protocol was developed according to the study objectives that were identified at the beginning. The interview protocol was based on the insights of the previous research. A pilot study was conducted on 4 participants to ascertain the appropriateness of these questions. The data from the pilot study was not included in the final data analysis. The mean length of the interviews was 70.14 minutes (range=60-81 minutes). The contents of the interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Table 2 presents the interview questions.

Data analysis

The thematic analysis method was used to analyze the data, which entails organizing and preparing, obtaining a sense, coding, generating categories or themes, and interpreting the data [33]. Codes were assigned to each participant to ascertain confidentiality. The reliability of the coding was maintained by multiple checks and rechecking data and codes. Following the procedure laid down in the thematic analysis method [33], four authors prepared the transcripts, read-reread them, and took initial notes to develop a close familiarity with the data (step 1). These authors independently assigned codes to the transcribed data by highlighting relevant and meaningful phrases or sentences. They also highlighted all the phrases or sentences that were closely related and assigned to previous codes and added new codes until the completion. When the coding task was over, the authors sorted the codes into major categories (step 2). The authors identified initial patterns (themes) by combining generated codes and categories and discarding vague or less relevant ones (step 3).

To check the usefulness, accuracy, and relevancy of the initial themes, the authors again compared them against the data, made appropriate changes, partially/wholly replaced them, and classified them into interrelated subthemes to make the themes reflect meaning inherent in the data. Since the data were coded independently by four authors, video conferencing was conducted to establish coherency among their codes, categories, and initial themes (step 4). The generated list of themes was defined and named by formulating the meaning and their capacity to understand the data (step 5). The authors prepared initial write-ups for each theme keeping the study objectives in mind along with employed methodology, analysis method, and meaning of the themes with examples in a storied form. This constituted the results section (step 6).

A priori criteria were adopted based on the initial questions to generate codes. The criteria were the impacts of COVID-19 on life, the methods of engagement, management of emotional issues, promotion of health habits, and management of the children’s activities by the joint and nuclear families during the pandemic. Saturation was recorded after completing 12 interviews when no new themes and codes were generated from further interviews consistent with the research questions [36]. Two more interviews each from joint and nuclear families were conducted to verify the saturation.

An iterative approach to complete analysis was employed to enhance the quality of coding. Iteration refers to a systematic, repetitive, and recursive process that involves a sequence of performing tasks multiple times in precisely the same manner each time. Thus, iteration is a reflexive process that sparks insight and helps in identifying meaning leading to refined focus and understanding [37]. A two-week gap was made between the initial and final scrutiny, and review of the transcriptions and codes to minimize the distortions caused by over-involvement in the data [38].

Results

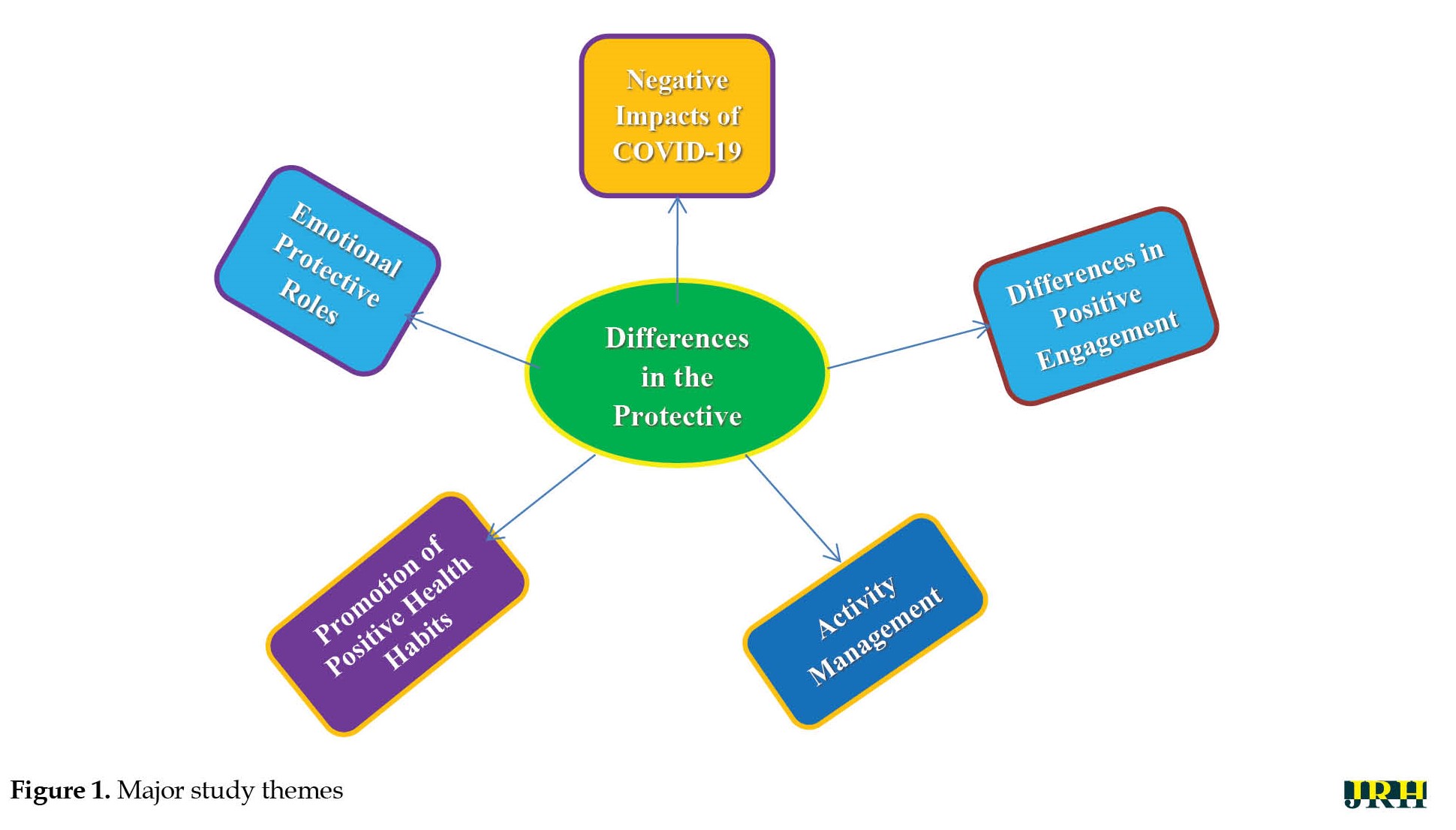

Following the thematic analysis method [33], five themes were generated, negative impacts of COVID-19, differences in positive engagement, emotional protective roles, promotion of positive health habits, and activity management. These themes (Figure 1) are presented below along with some representative quotes:

Theme 1: Negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

The distress, anxiety, uncertainties, suddenness, and restrictions of the lockdown had negative impacts on the well-living, children, and other members of the mothers of both families. These negative impacts were pervasive and affected all major aspects of their life. On the one hand, it burdened them with increasingly difficult-to-manage household and childcare responsibilities and on the other hand, reduced positive life outcomes. Some of these negative experiences were described by a mother in these words:

The pandemic has made our lives boring. It has also completely disturbed our routines of life (J_M_2).

The restrictions on social interactions even with neighbors, visitors, close relatives, distress and fear of loss of life of close relatives, and fear of infection may have seriously thwarted the positive emotional experiences of the majority of participating mothers in both families. One such gibe is below:

Our happiness has decreased. We now face strong restrictions on meeting new people, even neighbors (J_F_3).

The high pace of infection, negative and non-authentic news and rumors floating in social and mass media, unavailability of medicine or vaccine, loss of lives, and failure of developed countries to deal with its menace may have caused most participants to experience fear, distress and depressive symptoms during the lockdown. It was reflected in the following quote:

We should take extra care of our children and in-laws. It has also given unwanted extreme fear and anxiety (J_F_3).

Restrictions, social distancing, and quarantine measures implemented during the lockdown to prevent the further spreading of the pandemic severely affected earnings, employment opportunities, and prospects of all people alike. These factors may have led most participating mothers to experience and face undue burden, financial loss, and disturbed work-life. The following quote represents these realities:

Caring for family members has become a burden now. We have to engage our children without our wish. It caused the loss of work and made us frustrated (N_M_6).

Lack of undisrupted availability of essential teaching and learning resources (e.g. internet, computer) and uncertainties of school reopening may have seriously impacted the academic outcomes of children. These factors may have left the mothers with no way to cater to their children’s academic needs. It appeared in one quote below:

Students face great loss in their studies. They do not pay as much attention as in class (J_F_2).

Theme 2: Differences in positive engagements

School closure transferred entire responsibilities of engaging children in studies and play from school, peers, and neighbors to families. Since, joint and nuclear families differ significantly in the availability of human resources, activities, routine, temporal resources, the multiplicity of relations, age groups, resources of stimulation and information, the nature and methods of their children’s engagements during the restrictions of the lockdown may be different for them. For example, engagements in online classes, games, watching television (TV) and playing with mobile, household work, playing with the elders and siblings, listening to stories from grandparents, studying under the supervision of grandparents, and creative activities (such as drawing, painting or sketching) were the engagement methods of children during the pandemic period in the joint families. These descriptions have been nicely expressed in the following excerpts:

Instead of letting them watch unnecessary TV and mobiles, we engage them to help us with housework (J_F_2).

Since joint families avail and enjoy the abundance of human resources with many relationships and age groups, they may have successfully engaged their children in indoor games, studies, and story listening during the restrictions of the lockdown. Most mothers from joint families described their children’s involvement in games, recreational activities, and some other positive behavior with family members. These are nicely reflected in the following excerpt:

They are very happy to play with siblings or cousins and grandparents (J_M_2).

Joint families comprise members of different interests, needs, food habits, and routines due to differences in their roles, responsibilities, and age which, in turn, keep few members active. A positive method in joint families was to keep their children engaged in some household activities that can save them from being bored or feeling bad as well as remain connected with a sense of responsibility. The following excerpt closely reflected such engagements:

They do small household tasks, such as dusting, watering plants, and helping in the kitchen especially when the maid is on leave. They also help us in serving food to their grandparents (J_F_2).

Contrary to joint families, nuclear families have a limited number of family members, and limited relationships, temporal dimensions, and activities. With some similarities with joint families, the nuclear families differed in their engagement methods for their children during the pandemic lockdown. Most of them reported that the online class was one compulsory engagement, similar to the children of joint families. One departure was reported in more reliance on the children of these families on TV, mobiles, and indoor games. The following quote reflects these facts:

After the class is over, they watch TV or play mobile games (N_M_1).

Theme 3: Differences in emotional protective benefits

Since the joint families comprise members with different age groups and life experiences, their emotional make-up, emotional skills, and emotional maturity are varied with extended vertical and horizontal dimensions. Due to the availability of these resources in the form of grandparents, the mothers of the joint families may have described enhanced care, close supervision, regular interactions, and positive engagement in play, health, and other activities/methods used to provide emotional support to their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. Some of these descriptions are reflected in the following quote:

We tell them to wash their hands regularly with soap. They now understood that they have to be very careful during this time. (J_M_2)

The absence of grandparents, a limited number of members, and limited relationships in the nuclear families may have deprived them of positive emotional resources that can have been invested in dealing with the emotional issues of their children during the hard times of lockdown of the recent pandemic. They may have no alternatives but to promote their children’s engagement through more involvement in indoor games, TV, and mobile and irregular activities, and thus can provide limited emotional support to their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. These descriptions appeared in the following quote:

We play indoor games with them, such as ludo, chess, and carom to engage them. (N_F_6)

Since children of this age group need constant engagement in play and other activities and cannot be expected to sit like an adult, equally they cannot be assumed to be managed by single parents throughout the day for longer periods, such as during the lockdown accompanying strong restrictions on outside movements, activities, and relationships. Thus, mothers in nuclear families may have reported that it is difficult to manage and regulate their children’s emotional behaviors and feelings during the lockdown. The following quote reflects some of these experiences of a nuclear family mothers:

They show rigidity and boredom. We make them fear that if they go outside they will become ill (N_F_7).

Theme 4: Differences in the promotion of positive health habits

Grandparents in a joint family may have seen and experienced similar but less severe upheavals in their lives and may have gained the required skills, experiences, and cultural knowledge to deal with them successfully. This may be the reasons behind the descriptions of healthy diets, exercise, games and sports, protective habits, and the use of some Ayurvedic medicines by most mothers of the joint families to deal with health issues and to promote positive health in their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. These descriptions may be found in the following quote:

I try to take care of our children’s health. We include fresh vegetables in our meals. Fruits, such as apples, oranges, and bananas are among our daily needs. Taking milk before going to sleep is compulsory for children and elders (J_M_2).

The absence of senior family members may be seen as a lack of the above-discussed resources to prescribe and implement traditional positive health practices and lesser availability of family members to monitor and regulate the health behaviors of the children in the nuclear families. Due to these reasons, the mothers of the nuclear families may have no alternative but to go for limited options to promote positive health in their children during the lockdown. Thus, apart from some similarities, such as healthy diets and exercise in promoting positive health, the nuclear families may have imposed more restrictions on outdoor games with friends and may have permitted their children only to practice yoga, play indoor games and observe restrictions to avoid any mishap during the pandemic. These observations were reflected in the following quote:

I make him practice yoga in the morning. He practices Anulom-Vilom (a yogic exercise). We play with him and involve him in games regularly (N_M_6).

Theme 5: Differences in routine activity management strategies

The mothers of joint families described their children’s activity management through different methods during the lockdown. For example, they reported managing their children’s activities through an emphasis on their involvement in household tasks, team play, storytelling, and creative activities, and restrictions on excessive TV watching and use of mobile games. A selected quote reflecting these descriptions is given below:

We engage them in doing little household things so that they can be physically active and learn to manage household tasks (J_F_4).

Contrarily, nuclear families have less availability of human resources, limited relationship dimensions, and constricted emotional, experiential, knowledge, and temporal horizons. With some similarities to joint families, mothers in nuclear families may rely more on restrictive methods to manage their children’s activities. For instance, TV watching or playing with mobiles, in-door creative activities, playing indoor games, and limited involvement in household activities were the chief methods described by these mothers to manage the activities of their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. The following quote reflects these descriptions:

We manage his activities by allowing him to watch his favorite TV shows, cartoons, or recipes for cooking. It allows us to spare some time for some other important tasks (N_M_4).

Discussion

The results proved the contention that the perceived consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic were equally distressful to mothers in joint and nuclear families. The two families seem to differ significantly in managing the perceived threats caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to their lives, well-being, and overall existence. It appears that joint families may have provided for a broader temporal dimension, experiential resources, emotional pool, and buffer mechanisms to moderate the negative consequences of the pandemic compared to nuclear families. The presence of more members in joint families may be a positive and dependable source of social stimulation, positive experiences, care, positive life stories, control mechanisms, and positive attributions that may facilitate the protection and care of their children during these hard times. These strengths of joint families may have helped the joint families to bear the negative consequences of modernity. Conversely, the nuclear families may have been gripped by over-alertness, limited relationships, and a lack of human resources to deal with the flow of negative attributions and emotions arising out of the uncertainties and fear of the pandemic.

A joint family has been suggested to be the chief vehicle of collective values and practices, including interdependence, mutuality, and community orientation [39, 40]. Contrarily, a nuclear family is born out of the influence of a postmodern lifestyle, the proliferation of materialistic values, and individualistic achievement orientation. The two value systems may cultivate two distinct modes of relationships, care and life goals having characteristically different impacts on their children’s life outcomes. The joint families had more resources for their children’s participation in creativity, studies, exercise, and entertainment as compared to the nuclear families. Likewise, the joint families appeared to resolve easily the emotional grievances, promote positive emotional engagement, and support emotionally compared to nuclear families. Significant differences were also described regarding their children’s food habits, and health grievances. Compared to nuclear families, joint families have a more positive role in managing children’s play behaviors, health habits and use of electronic media. Thus, the diversity in the patterns of moral, emotional, interpersonal, temporal, and other resources may have been acting behind the described dissimilar life outcomes of the children of the two families.

The recent pandemic is described as having similar negative impacts on the joint and nuclear families (theme 1). The mothers of both families described almost similar perceived negative consequences for them and their families. Research suggests that the uncertain, novel, and fatal nature of the pandemic gives birth to a set of epidemic-like psycho-social processes that may spread at a faster pace in different forms to individuals and collectives [2, 41]. This psycho-social epidemic may carry suspicion, insecurity, irrationality, misinformation, panic, stigmatization, avoidance, segregation, abuse, and theories of the origin of disease and its effects and metaphysical explanations among educated as well as illiterate people [42, 43]. These by-products of the recent pandemic may be the source of the perceived distress of participating mothers in two families.

The pandemic restrictions have reduced social interaction. All individuals, since they are human, have a strong need to interact to make sense of their world, get satisfaction and happiness, and live well [44]. Due to the lack of similar past experiences, the loss of social connection may cause them to perceive stress. Similar to the results of the present study, previous studies reported negative psychological consequences caused by the recent pandemic. For example, it was suggested to lead to confusion, stress, anxiety, restrictions, fear of infection, frustration, boredom, loss and stigma [31, 45], disturbance in emotional attachment [1], and poor well-being among children and adults [2, 4, 5, 46].

Differences in positive engagement, emotional protective roles, promotion of positive health habits, and activity management of the joint, and nuclear families have been described (themes 2-5). Along with some similarities, the two families differ significantly in the way they engaged their children during the pandemic. The joint families describe that they engage their children through play with elders and siblings, storytelling by grandparents, and creative activities while the nuclear families heavily rely on the use of television, mobile and indoor games. These differences in positive engagement methods of the two families may be due to the differences in the available resources in the form of elders, multiple relationships, and temporal dimensions. Previous studies have also reported that joint families provide more alternatives for interactions, play, and creative activities for children [47].

The elders have long and rich experiences of life, positive stories, wisdom, emotional maturity, and forgiveness [48, 49] and show more agreeableness, and lesser neuroticism [50]. Elders may also carry generativity, which involves finding meaningful work and contributing to the development of others through activities, such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children [51]. These resources in the form of elders in joint families may have supported them to exercise more positive engagements with their children than the nuclear families. For the parents of nuclear families, dealing with the restrictions of the pandemic may have become more stressful who have to make a balance between their personal life, work, raising children, and loneliness [52]. These challenges may have reduced the psychological resources in the hands of the parents of nuclear families to more positively engage and protect their children.

The current study is not without limitations. The use of a small sample was its first limitation. The second limitation was that only full-time mothers were included to describe their experiences and perceived life outcomes, strategies, and methods for caring, managing, and involving their children during the lockdown. The involvement of fathers, the whole family, and the children themselves may have helped to come up with more useful findings and insights. The use of the qualitative method was the third limitation. We suggest future researchers to observe precautions while generalizing the results of the current study.

Conclusion

The joint and nuclear families showed dissimilar resources and mechanisms to deal with their children’s issues during the restrictions of the COVID-19 lockdown. The joint families evinced a set of robust positive resources, mechanisms, temporal dimensions, relational resources, knowledge, and relevant support to deal with the task of engaging their children. Conversely, the nuclear families showed dissimilar resources and mechanisms, characterized by slight restrictions, over-alertness, lack of broader experiences, and poor socio-emotional repertoire. Moreover, joint families are said to carry collective values, which reflect more support, cooperation, care, interdependence, discipline, cultural knowledge, and conflict resolution mechanisms. Conversely, the nuclear families carry individualistic values that catalyze independence, narrow temporal dimension, individualism, individual achievement orientation, and limited support. The differences in these resources and mechanisms may be argued to surface in their dissimilar abilities to protect and positively engage their children during the recent pandemic.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dr Hari Singh Gour University (Code: DHSGV//IEC/2021/9).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Due to the unprecedented and unparalleled restrictions, fear, and uncertainty, the COVID-19 pandemic has created an indescribable situation of anguish and pain for all human beings. It has created severe distress, anxiety, uncertainty, and challenges to the life outcomes of children and adults [1, 2]. United Nations Organization (UN) has observed that children are one of the biggest sufferers of this pandemic and its negative influences may be significantly influenced by the economic and social conditions of families and their health conditions [3]. Children face acute unavailability of the needed resources, social support, and services, which exposes them to face psychological distress, violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation which, in turn, may adversely affect their development and well-being [4, 5].

A phone-based study of 144 families from Canada during April-May 2020 also revealed that parents and children showed family-related changes, health problems, and fears in children aged 9-12 years and their parents [6]. Research in India also observed that parents and families experienced a constant sense of loss of social networks, employment, financial security, and relatives which, in turn, may negatively impact the quality of relationships [7]. Given the dependence of 370 million children (0-14 years) in India on positive family processes for a variety of outcomes, their care during this period may be challenging due to social disruptions, gender norm changes, school closure, lack of extracurricular/outdoor activities, new eating and sleeping habits, lack of peer-relationships and boredom [7, 8]. These negative consequences for children may go beyond imagination since the current pandemic is more traumatic, pervasive, and uncertain [2, 9, 10].

The family acts as a crucial and universal agency that provides care for children. Various forms of families with different structures and functions are found. One typology is a joint family and a nuclear family. According to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary (2020), a joint family is a consanguineal unit that includes two or more generations of kindred related through either paternal or maternal line who maintain a common residence and are subject to common social, economic, and religious regulations [11]. A nuclear family refers to a group consisting only parents and children [12]. The joint family system is the major vehicle of collective values and practices, guided by shared identity, deep attachments, unique socialization, emotionality, meaning, relationships, concern for others, interdependence, and relatively permanent relationships [13–16]. In parallel, a nuclear family is based on individualistic values and lays emphasis on individual identity, independence, self-esteem, and personal achievements [13, 17].

Dissimilar life outcomes for children are associated with the two-family systems. For example, a joint family is more supportive of children to achieve psychological well-being than a nuclear family [18]. The differences in the outcomes of children of the two family systems have been assumed to be the results of dissimilarities in parent relations and social relations [19, 20], kin rivalry [21] and parental resources, the mental health of parents, parent-child relations, quality of relationships between parents and parental discrepancy [22, 23]. These differences facilitate the children of joint families to show better performance on the various components of psychological well-being, such as autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations, purpose in life, and self-acceptance compared to their nuclear family counterparts [18]. Besides, children from joint families show lower behavioral problems [24] and higher emotional maturity than children from nuclear families [25].

Joint families reflect a collectivistic culture [26], characterized by strong family bonds, positive environments, close monitoring, and promotion of family activities helping their children to safeguard from ill consequences in life [27]. They also emphasize interdependence, obedience, proper behaviour, social obligations, and group achievement [28]. Conversely, nuclear families represent an individualistic culture that emphasizes independence, individual rights, and self-sufficiency [29]. Thus, nuclear families nurture their children’s autonomy, self-interest, self-reliance, self-expression, and individual identity [28]. These two family systems provide different kinds of socialization opportunities and engagements for their children [30]. Due to the underexploration of the impacts of COVID-19 on children, it was necessitated to understand the underlying dynamics of the protective roles of joint and nuclear families in shaping their life outcomes during COVID-19.

Although the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are well-documented for the population, little research is conducted on its impacts on parents, families, and children [1, 31]. The distress of the recent pandemic has severely influenced the life outcomes of children similar to adults [1]. The study of children is also critical for other reasons. Families differ in providing care and support to their children. For example, a joint family may provide more live, long-term, and varied positive stimulations emanating from the dynamics of relationships among children, siblings, parents, grandparents, and other relatives. On the other hand, a nuclear family may become naturally restrictive and less live and short-term stimulating due to the limited size and restricted variety of relationships.

Recent research suggests that the recent pandemic opens up new avenues in social and cultural relationships along with inequality, distress, and discrimination [32]. These new opportunities can be effectively captured with qualitative studies since they provide reliable ways to capture, individual, group, and community responses as well as help to make sense of meaning, interactions, new insights, health, and illness. Instead of focusing on what, they help to understand why and how, they can also fill the gap between assumptions and realities and help to understand the social, cultural, and political aspects of a phenomenon [32]. Thus, in the present case, a qualitative method may also help to better understand the underlying processes and mechanisms of the impacts of the severe restrictions and quarantine during the COVID-19 lockdown.

The current study chose children aged 9 to 12 years since the children of this age group remain completely dependent on their parents and other family members for their satisfaction of needs and care to a large extent. Besides, these children can speak out their demands and show understandable emotional and behavioral responses. This makes their behavior comprehensive, stable, and patterned. Besides, these children also understand the necessity and compulsion of adherence to the restrictions of the lockdown. In this backdrop, the study aims to explore the perceived protective roles of joint and nuclear families in shaping the life outcomes of children aged 9 to 12 years, during the restrictions of the COVID-19 lockdown through a qualitative research design. The study results showed that COVID-19 is traumatic, pervasive, and uncertain and thus, it may leave negative marks on children’s development. Joint and nuclear families differ in their protective strengths for children in adversities, such as the recent pandemic. The two families vary in their positive engagements, emotional resources, and activity management methods for their children.

Methods

This study was conducted using a qualitative research design. A realist approach was used to understand and theorize the meaning, experience, and motivations inherent in the data in an uncomplicated way [33]. The study was conducted during June and July 2020 at Sagar City of Madhya Pradesh, India.

Participants

Sixteen full-time mothers (age range=33-45 years) were selected. Eight mothers were from joint families with Mean±SD of 41.63±2.62 and 8 mothers were from nuclear families with Mean±SD of 37.50±3.07. Their children’s age was from 9 to 12 years (Mean±SD, 10.66±1.17) (Table 1).

We chose only full-time mothers since they represent an information-rich group and were able to describe and reflect upon their children’s behaviors and experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown [34]. The selection of full-time mothers has been reported to be useful as a rich source of information regarding their children’s behaviors in the approximately current age group in some recent studies [2, 35].

The inclusion criteria included a full-time mother, affiliation with either a joint family or nuclear family, and a mother of at least one child with an age range from 9 to 12 years. The information about the study was circulated among the prospective participants through email, Facebook, and WhatsApp messages with full descriptions by the authors’ identifiers. Initially, 27 mothers gave their consent on the telephone, but 11 of them did not participate in the study due to their different personal reasons. Thus, 16 full-time mothers finally participated who belonged to sub-urban middle-class families and mostly adhered to the Hindu religion. Informed consent was obtained from all participants by telephone.

Data collection

A quasi-structured interview protocol was used to collect the data through telephone calls. The structure of the protocol was developed according to the study objectives that were identified at the beginning. The interview protocol was based on the insights of the previous research. A pilot study was conducted on 4 participants to ascertain the appropriateness of these questions. The data from the pilot study was not included in the final data analysis. The mean length of the interviews was 70.14 minutes (range=60-81 minutes). The contents of the interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Table 2 presents the interview questions.

Data analysis

The thematic analysis method was used to analyze the data, which entails organizing and preparing, obtaining a sense, coding, generating categories or themes, and interpreting the data [33]. Codes were assigned to each participant to ascertain confidentiality. The reliability of the coding was maintained by multiple checks and rechecking data and codes. Following the procedure laid down in the thematic analysis method [33], four authors prepared the transcripts, read-reread them, and took initial notes to develop a close familiarity with the data (step 1). These authors independently assigned codes to the transcribed data by highlighting relevant and meaningful phrases or sentences. They also highlighted all the phrases or sentences that were closely related and assigned to previous codes and added new codes until the completion. When the coding task was over, the authors sorted the codes into major categories (step 2). The authors identified initial patterns (themes) by combining generated codes and categories and discarding vague or less relevant ones (step 3).

To check the usefulness, accuracy, and relevancy of the initial themes, the authors again compared them against the data, made appropriate changes, partially/wholly replaced them, and classified them into interrelated subthemes to make the themes reflect meaning inherent in the data. Since the data were coded independently by four authors, video conferencing was conducted to establish coherency among their codes, categories, and initial themes (step 4). The generated list of themes was defined and named by formulating the meaning and their capacity to understand the data (step 5). The authors prepared initial write-ups for each theme keeping the study objectives in mind along with employed methodology, analysis method, and meaning of the themes with examples in a storied form. This constituted the results section (step 6).

A priori criteria were adopted based on the initial questions to generate codes. The criteria were the impacts of COVID-19 on life, the methods of engagement, management of emotional issues, promotion of health habits, and management of the children’s activities by the joint and nuclear families during the pandemic. Saturation was recorded after completing 12 interviews when no new themes and codes were generated from further interviews consistent with the research questions [36]. Two more interviews each from joint and nuclear families were conducted to verify the saturation.

An iterative approach to complete analysis was employed to enhance the quality of coding. Iteration refers to a systematic, repetitive, and recursive process that involves a sequence of performing tasks multiple times in precisely the same manner each time. Thus, iteration is a reflexive process that sparks insight and helps in identifying meaning leading to refined focus and understanding [37]. A two-week gap was made between the initial and final scrutiny, and review of the transcriptions and codes to minimize the distortions caused by over-involvement in the data [38].

Results

Following the thematic analysis method [33], five themes were generated, negative impacts of COVID-19, differences in positive engagement, emotional protective roles, promotion of positive health habits, and activity management. These themes (Figure 1) are presented below along with some representative quotes:

Theme 1: Negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

The distress, anxiety, uncertainties, suddenness, and restrictions of the lockdown had negative impacts on the well-living, children, and other members of the mothers of both families. These negative impacts were pervasive and affected all major aspects of their life. On the one hand, it burdened them with increasingly difficult-to-manage household and childcare responsibilities and on the other hand, reduced positive life outcomes. Some of these negative experiences were described by a mother in these words:

The pandemic has made our lives boring. It has also completely disturbed our routines of life (J_M_2).

The restrictions on social interactions even with neighbors, visitors, close relatives, distress and fear of loss of life of close relatives, and fear of infection may have seriously thwarted the positive emotional experiences of the majority of participating mothers in both families. One such gibe is below:

Our happiness has decreased. We now face strong restrictions on meeting new people, even neighbors (J_F_3).

The high pace of infection, negative and non-authentic news and rumors floating in social and mass media, unavailability of medicine or vaccine, loss of lives, and failure of developed countries to deal with its menace may have caused most participants to experience fear, distress and depressive symptoms during the lockdown. It was reflected in the following quote:

We should take extra care of our children and in-laws. It has also given unwanted extreme fear and anxiety (J_F_3).

Restrictions, social distancing, and quarantine measures implemented during the lockdown to prevent the further spreading of the pandemic severely affected earnings, employment opportunities, and prospects of all people alike. These factors may have led most participating mothers to experience and face undue burden, financial loss, and disturbed work-life. The following quote represents these realities:

Caring for family members has become a burden now. We have to engage our children without our wish. It caused the loss of work and made us frustrated (N_M_6).

Lack of undisrupted availability of essential teaching and learning resources (e.g. internet, computer) and uncertainties of school reopening may have seriously impacted the academic outcomes of children. These factors may have left the mothers with no way to cater to their children’s academic needs. It appeared in one quote below:

Students face great loss in their studies. They do not pay as much attention as in class (J_F_2).

Theme 2: Differences in positive engagements

School closure transferred entire responsibilities of engaging children in studies and play from school, peers, and neighbors to families. Since, joint and nuclear families differ significantly in the availability of human resources, activities, routine, temporal resources, the multiplicity of relations, age groups, resources of stimulation and information, the nature and methods of their children’s engagements during the restrictions of the lockdown may be different for them. For example, engagements in online classes, games, watching television (TV) and playing with mobile, household work, playing with the elders and siblings, listening to stories from grandparents, studying under the supervision of grandparents, and creative activities (such as drawing, painting or sketching) were the engagement methods of children during the pandemic period in the joint families. These descriptions have been nicely expressed in the following excerpts:

Instead of letting them watch unnecessary TV and mobiles, we engage them to help us with housework (J_F_2).

Since joint families avail and enjoy the abundance of human resources with many relationships and age groups, they may have successfully engaged their children in indoor games, studies, and story listening during the restrictions of the lockdown. Most mothers from joint families described their children’s involvement in games, recreational activities, and some other positive behavior with family members. These are nicely reflected in the following excerpt:

They are very happy to play with siblings or cousins and grandparents (J_M_2).

Joint families comprise members of different interests, needs, food habits, and routines due to differences in their roles, responsibilities, and age which, in turn, keep few members active. A positive method in joint families was to keep their children engaged in some household activities that can save them from being bored or feeling bad as well as remain connected with a sense of responsibility. The following excerpt closely reflected such engagements:

They do small household tasks, such as dusting, watering plants, and helping in the kitchen especially when the maid is on leave. They also help us in serving food to their grandparents (J_F_2).

Contrary to joint families, nuclear families have a limited number of family members, and limited relationships, temporal dimensions, and activities. With some similarities with joint families, the nuclear families differed in their engagement methods for their children during the pandemic lockdown. Most of them reported that the online class was one compulsory engagement, similar to the children of joint families. One departure was reported in more reliance on the children of these families on TV, mobiles, and indoor games. The following quote reflects these facts:

After the class is over, they watch TV or play mobile games (N_M_1).

Theme 3: Differences in emotional protective benefits

Since the joint families comprise members with different age groups and life experiences, their emotional make-up, emotional skills, and emotional maturity are varied with extended vertical and horizontal dimensions. Due to the availability of these resources in the form of grandparents, the mothers of the joint families may have described enhanced care, close supervision, regular interactions, and positive engagement in play, health, and other activities/methods used to provide emotional support to their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. Some of these descriptions are reflected in the following quote:

We tell them to wash their hands regularly with soap. They now understood that they have to be very careful during this time. (J_M_2)

The absence of grandparents, a limited number of members, and limited relationships in the nuclear families may have deprived them of positive emotional resources that can have been invested in dealing with the emotional issues of their children during the hard times of lockdown of the recent pandemic. They may have no alternatives but to promote their children’s engagement through more involvement in indoor games, TV, and mobile and irregular activities, and thus can provide limited emotional support to their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. These descriptions appeared in the following quote:

We play indoor games with them, such as ludo, chess, and carom to engage them. (N_F_6)

Since children of this age group need constant engagement in play and other activities and cannot be expected to sit like an adult, equally they cannot be assumed to be managed by single parents throughout the day for longer periods, such as during the lockdown accompanying strong restrictions on outside movements, activities, and relationships. Thus, mothers in nuclear families may have reported that it is difficult to manage and regulate their children’s emotional behaviors and feelings during the lockdown. The following quote reflects some of these experiences of a nuclear family mothers:

They show rigidity and boredom. We make them fear that if they go outside they will become ill (N_F_7).

Theme 4: Differences in the promotion of positive health habits

Grandparents in a joint family may have seen and experienced similar but less severe upheavals in their lives and may have gained the required skills, experiences, and cultural knowledge to deal with them successfully. This may be the reasons behind the descriptions of healthy diets, exercise, games and sports, protective habits, and the use of some Ayurvedic medicines by most mothers of the joint families to deal with health issues and to promote positive health in their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. These descriptions may be found in the following quote:

I try to take care of our children’s health. We include fresh vegetables in our meals. Fruits, such as apples, oranges, and bananas are among our daily needs. Taking milk before going to sleep is compulsory for children and elders (J_M_2).

The absence of senior family members may be seen as a lack of the above-discussed resources to prescribe and implement traditional positive health practices and lesser availability of family members to monitor and regulate the health behaviors of the children in the nuclear families. Due to these reasons, the mothers of the nuclear families may have no alternative but to go for limited options to promote positive health in their children during the lockdown. Thus, apart from some similarities, such as healthy diets and exercise in promoting positive health, the nuclear families may have imposed more restrictions on outdoor games with friends and may have permitted their children only to practice yoga, play indoor games and observe restrictions to avoid any mishap during the pandemic. These observations were reflected in the following quote:

I make him practice yoga in the morning. He practices Anulom-Vilom (a yogic exercise). We play with him and involve him in games regularly (N_M_6).

Theme 5: Differences in routine activity management strategies

The mothers of joint families described their children’s activity management through different methods during the lockdown. For example, they reported managing their children’s activities through an emphasis on their involvement in household tasks, team play, storytelling, and creative activities, and restrictions on excessive TV watching and use of mobile games. A selected quote reflecting these descriptions is given below:

We engage them in doing little household things so that they can be physically active and learn to manage household tasks (J_F_4).

Contrarily, nuclear families have less availability of human resources, limited relationship dimensions, and constricted emotional, experiential, knowledge, and temporal horizons. With some similarities to joint families, mothers in nuclear families may rely more on restrictive methods to manage their children’s activities. For instance, TV watching or playing with mobiles, in-door creative activities, playing indoor games, and limited involvement in household activities were the chief methods described by these mothers to manage the activities of their children during the restrictions of the lockdown. The following quote reflects these descriptions:

We manage his activities by allowing him to watch his favorite TV shows, cartoons, or recipes for cooking. It allows us to spare some time for some other important tasks (N_M_4).

Discussion

The results proved the contention that the perceived consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic were equally distressful to mothers in joint and nuclear families. The two families seem to differ significantly in managing the perceived threats caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to their lives, well-being, and overall existence. It appears that joint families may have provided for a broader temporal dimension, experiential resources, emotional pool, and buffer mechanisms to moderate the negative consequences of the pandemic compared to nuclear families. The presence of more members in joint families may be a positive and dependable source of social stimulation, positive experiences, care, positive life stories, control mechanisms, and positive attributions that may facilitate the protection and care of their children during these hard times. These strengths of joint families may have helped the joint families to bear the negative consequences of modernity. Conversely, the nuclear families may have been gripped by over-alertness, limited relationships, and a lack of human resources to deal with the flow of negative attributions and emotions arising out of the uncertainties and fear of the pandemic.

A joint family has been suggested to be the chief vehicle of collective values and practices, including interdependence, mutuality, and community orientation [39, 40]. Contrarily, a nuclear family is born out of the influence of a postmodern lifestyle, the proliferation of materialistic values, and individualistic achievement orientation. The two value systems may cultivate two distinct modes of relationships, care and life goals having characteristically different impacts on their children’s life outcomes. The joint families had more resources for their children’s participation in creativity, studies, exercise, and entertainment as compared to the nuclear families. Likewise, the joint families appeared to resolve easily the emotional grievances, promote positive emotional engagement, and support emotionally compared to nuclear families. Significant differences were also described regarding their children’s food habits, and health grievances. Compared to nuclear families, joint families have a more positive role in managing children’s play behaviors, health habits and use of electronic media. Thus, the diversity in the patterns of moral, emotional, interpersonal, temporal, and other resources may have been acting behind the described dissimilar life outcomes of the children of the two families.

The recent pandemic is described as having similar negative impacts on the joint and nuclear families (theme 1). The mothers of both families described almost similar perceived negative consequences for them and their families. Research suggests that the uncertain, novel, and fatal nature of the pandemic gives birth to a set of epidemic-like psycho-social processes that may spread at a faster pace in different forms to individuals and collectives [2, 41]. This psycho-social epidemic may carry suspicion, insecurity, irrationality, misinformation, panic, stigmatization, avoidance, segregation, abuse, and theories of the origin of disease and its effects and metaphysical explanations among educated as well as illiterate people [42, 43]. These by-products of the recent pandemic may be the source of the perceived distress of participating mothers in two families.

The pandemic restrictions have reduced social interaction. All individuals, since they are human, have a strong need to interact to make sense of their world, get satisfaction and happiness, and live well [44]. Due to the lack of similar past experiences, the loss of social connection may cause them to perceive stress. Similar to the results of the present study, previous studies reported negative psychological consequences caused by the recent pandemic. For example, it was suggested to lead to confusion, stress, anxiety, restrictions, fear of infection, frustration, boredom, loss and stigma [31, 45], disturbance in emotional attachment [1], and poor well-being among children and adults [2, 4, 5, 46].

Differences in positive engagement, emotional protective roles, promotion of positive health habits, and activity management of the joint, and nuclear families have been described (themes 2-5). Along with some similarities, the two families differ significantly in the way they engaged their children during the pandemic. The joint families describe that they engage their children through play with elders and siblings, storytelling by grandparents, and creative activities while the nuclear families heavily rely on the use of television, mobile and indoor games. These differences in positive engagement methods of the two families may be due to the differences in the available resources in the form of elders, multiple relationships, and temporal dimensions. Previous studies have also reported that joint families provide more alternatives for interactions, play, and creative activities for children [47].

The elders have long and rich experiences of life, positive stories, wisdom, emotional maturity, and forgiveness [48, 49] and show more agreeableness, and lesser neuroticism [50]. Elders may also carry generativity, which involves finding meaningful work and contributing to the development of others through activities, such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children [51]. These resources in the form of elders in joint families may have supported them to exercise more positive engagements with their children than the nuclear families. For the parents of nuclear families, dealing with the restrictions of the pandemic may have become more stressful who have to make a balance between their personal life, work, raising children, and loneliness [52]. These challenges may have reduced the psychological resources in the hands of the parents of nuclear families to more positively engage and protect their children.

The current study is not without limitations. The use of a small sample was its first limitation. The second limitation was that only full-time mothers were included to describe their experiences and perceived life outcomes, strategies, and methods for caring, managing, and involving their children during the lockdown. The involvement of fathers, the whole family, and the children themselves may have helped to come up with more useful findings and insights. The use of the qualitative method was the third limitation. We suggest future researchers to observe precautions while generalizing the results of the current study.

Conclusion

The joint and nuclear families showed dissimilar resources and mechanisms to deal with their children’s issues during the restrictions of the COVID-19 lockdown. The joint families evinced a set of robust positive resources, mechanisms, temporal dimensions, relational resources, knowledge, and relevant support to deal with the task of engaging their children. Conversely, the nuclear families showed dissimilar resources and mechanisms, characterized by slight restrictions, over-alertness, lack of broader experiences, and poor socio-emotional repertoire. Moreover, joint families are said to carry collective values, which reflect more support, cooperation, care, interdependence, discipline, cultural knowledge, and conflict resolution mechanisms. Conversely, the nuclear families carry individualistic values that catalyze independence, narrow temporal dimension, individualism, individual achievement orientation, and limited support. The differences in these resources and mechanisms may be argued to surface in their dissimilar abilities to protect and positively engage their children during the recent pandemic.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dr Hari Singh Gour University (Code: DHSGV//IEC/2021/9).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, Fang SF, Jiao FY, Pettoello-Mantovani M, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2020; 221:264-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013]

- Tiwari GK, Singh AK, Parihar P, Pandey R, Sharma DN, Rai PK. Understanding the perceived psychological distress and health outcomes of children during COVID-19 pandemic. Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2023; 40(1):103-14. [DOI:10.1080/20590776.2021.1899749]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Group. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on children. United Nations Sustainable Development Group: New York; 2020. [Link]

- No author. COVID-19’s devastating impact on children [Internet]. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2020. [Link]

- Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020; 4(6):421. [DOI:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7]

- Suffren S, Dubois-Comtois K, Lemelin JP, St-Laurent D, Milot T. Relations between child and parent fears and changes in family functioning related to covid-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1786. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18041786]

- Parekh BJ, Dalwai SH. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children in India. Indian Pediatrics. 2020; 57:1107. [DOI:10.1007/s13312-020-2060-y]

- Saurabh K, Ranjan S. Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to covid-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020; 87(7):532-6. [DOI:10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3]

- Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of covid-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020; 180(6):817-8. [DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562]

- Pandey R, Tiwari GK, Rai PK. The Independent and Interdependent Self-affirmations in Action: Understanding their dynamics in India during COVID-19. Authorea. 2020. [UnPublished]. [Link]

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Definition of joint family Springfield: Merriam-Webster publisher; 2023. [Link]

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Definition of nuclear family Springfield: Merriam-Webster publisher; 2023. [Link]

- Cai H, Sedikides C, Jiang L. Familial self as a potent source of affirmation: Evidence from China. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2013; 4(5):529-37. [DOI:10.1177/1948550612469039]

- Gaines SO, Marelich WD, Bledsoe KL, Steers WN, Henderson MC, Granrose CS, et al. Links between race/ethnicity and cultural values as mediated by racial/ethnic identity and moderated by gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997; 72(6):1460-76. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1460]

- Hoshino-Browne E, Zanna AS, Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Kitayama S, Lackenbauer S. On the cultural guises of cognitive dissonance: The case of Easterners and Westerners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005; 89(3):294-310. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.294]

- Scabini E, Manzi C. Family processes and identity. In: Schwartz S, Luyckx K, Vignoles V, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_23]

- Gupta M, Sukamto K. Cultural communicative styles: The case of India and Indonesia. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language. 2020; 8(2):105-20. [Link]

- Gul N, Ghani N, Alvi SM, Kazmi F, Shah AA. Family system’s role in the psychological well-being of the children. Khyber Medical University Journal. 2017; 9(1):29-32. [Link]

- Bernardi F, Härkönen J, Boertien D, Rydell A, Bastaits K, Mortelmans D. Effects of family forms and dynamics on children’s well-being and life chances: Literature review. Maastricht: European :union:'s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement; 2013. [Link]

- Mackay R. The impact of family structure and family change on child outcomes: A personal reading of the research literature. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. 2005; 24(4):111-33. [Link]

- Kreppner K, Lerner RM. Family systems and life-span development. New York: Psychology Press; 1989. [DOI:10.4324/9780203771280]

- Fomby P, Cherlin AJ. Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review. 2007; 72(2):181-204. [DOI:10.1177/000312240707200203]

- Sun Y, Li Y. Children’s Well-Being during parents’ marital disruption process: A pooled time-series analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002; 64(2):472-88. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00472.x]

- Kauts A, Kaur B. A study of children’s behaviour in relation to family environment and technological exposure at pre primary stage. MIER Journal of Educational Studies, Trends and Practices. 2016; 1(2):111–28. [Link]

- Kondiba BV, Hari KS. Emotional maturity among joint family and nuclear family children. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2018; 6(2):109-12. [Link]

- Chadda R, Deb K. Indian family systems, collectivistic society and psychotherapy. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 55(supple2):299-309. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.105555]

- Tilley N, Sidebottom A. Handbook of crime prevention and community safety. London: Routledge; 2017. [DOI:10.4324/9781315724393]

- Tas J, Marshall IH, Enzmann D, Killias M, Steketee M, Gruszczynska B. The many faces of youth crime: Contrasting theoretical perspectives on juvenile delinquency across countries and cultures. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4419-9455-4]

- Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2011; 2(1):1-26. [DOI:10.9707/2307-0919.1014]

- Kotlaja MM. Cultural contexts of individualism vs. collectivism: Exploring the relationships between family bonding, supervision and deviance. European Journal of Criminology. 2020; 17(3):288-305. [DOI:10.1177/1477370818792482]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020; 395(10227):912-20. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8]

- Teti M, Schatz E, Liebenberg L. Methods in the time of covid-19: The vital role of qualitative inquiries. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2020; 19:160940692092096. [DOI:10.1177/1609406920920962]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3(2):77-101. [DOI:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2015. [Link]

- Ahirwar G, Tiwari GK, Rai PK. Exploring the nature, attributes and consequences of forgiveness in children: A qualitative study. Psychological Thought. 2019; 12(2):214-31. [DOI:10.5964/psyct.v12i2.347]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity. 2018; 52(4):1893-907. [DOI:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8]

- Srivastava P, Hopwood N. A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2009; 8(1):76-84. [DOI:10.1177/160940690900800107]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2012. [DOI:10.4135/9781483384436]

- Choi J, So J. Effects of self-affirmation on message persuasiveness: A cross-cultural study of the U.S. and South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication. 2019; 29(2):128-48. [DOI:10.1080/01292986.2018.1555265]

- Tiwari GK, Kashyap AK, Rai PK, Tiwari RP, Pandey R. Collective affirmation in action: Understanding the success of lockdown in India during the first wave of the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Research and Health. 2022; 12(3):137-50. [Link]

- Strong P. Epidemic psychology: A model. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1990; 12(3):249-59. [DOI:10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347150]

- Tiwari GK, Rai PK, Dwivedi A, Ray B, Pandey A, Pandey R. A narrative thematic analysis of the perceived psychological distress and health outcomes in Indian adults during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society. 2023; 28(1):213-29. [DOI:10.12681/psy_hps.28062]

- Weber J, Goldmeier D. Medicine and the Media. British Medical Journal. 1983; 287:420. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.287.6389.420]

- Sun J, Harris K, Vazire S. Is well-being associated with the quantity and quality of social interactions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2020; 119(6):1478-96. [DOI:10.1037/pspp0000272]

- Racine N, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Korczak DJ, McArthur B, Madigan S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 292:113307. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307]

- Ghosh R, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Dubey S. Impact of COVID-19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrics. 2020; 72(3):226-35. [DOI:10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9]

- Bisht S, Sinha D. Socialization, family, and psychological differentiation. In: Socialization of the Indian child. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co; 1981. [Link]

- Ghaemmaghami P, Allemand M, Martin M. Forgiveness in younger, middle-aged and older adults: Age and gender matters. Journal of Adult Development. 2011; 18(4):192-203. [DOI:10.1007/s10804-011-9127-x]

- Hayward RD, Krause N. Trajectories of change in dimensions of forgiveness among older adults and their association with religious commitment. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2013; 16(6):10.1080/13674676.2012.712955. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2012.712955]

- Steiner M, Allemand M, McCullough ME. Do agreeableness and neuroticism explain age differences in the tendency to forgive others? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012; 38(4):441-53. [DOI:10.1177/0146167211427923]

- Erikson EH, Erikson JM. The life cycle completed. Extended version. New York: W.W. Norton; 1998. [Link]