Volume 15, Issue 3 (May & June 2025)

J Research Health 2025, 15(3): 269-282 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Singh A K, Tiwari G K. Exploring Gender Differences in Unforgiveness: A Thematic Analysis of Experiences and Expressions in Males and Females. J Research Health 2025; 15 (3) :269-282

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2603-en.html

URL: http://jrh.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-2603-en.html

1- Amity Institute of Behavioural and Allied Sciences (AIBAS), Amity University, Jaipur, India.

2- Department of Psychology, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, India. ,gyaneshpsychology@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, India. ,

Full-Text [PDF 724 kb]

(241 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1149 Views)

Full-Text: (173 Views)

Introduction

Inforgiveness is defined as a cold emotion involving resentment, bitterness, and motivated avoidance or retribution toward a transgressor [1, 2]. It is a conscious state, in which individuals harbor negative feelings toward the perpetrator. Research on unforgiveness has been relatively sparse, with many researchers describing it simply as the opposite of forgiveness [3]. It is often measured through the inventory of interpersonal motivations related to transgressions [4], levels of resentment toward the transgressor [5], or by reversing forgiveness measures [6]. Unforgiveness is distinct from general hostility or the mere absence of forgiveness, as it reflects persistent negative emotions and motivation to retaliate or avoid the transgressor. This emotional state is associated with interpersonal conflict and emotional distress, with personality traits and gender influencing its manifestation [1, 7].

Unforgiveness, often defined as resentment, bitterness, and avoidance or retribution, is measured using tools, like the transgression-related interpersonal motivations inventory (TRIM) and reversed forgiveness scales [8]. However, these approaches tend to simplify unforgiveness as the opposite of forgiveness, overlooking its emotional complexity. Self-reports on resentment and negative emotions are also used, but they may miss key cognitive and behavioral dimensions. Research typically frames unforgiveness as merely the absence of forgiveness, limiting a deeper understanding of its distinct effects. Unforgiveness, involving emotions, like bitterness, can have protective functions beyond its negative impact. A more nuanced approach is needed to explore how unforgiveness may contribute to emotional resilience and protect individuals from harm in relational dynamics [7].

Stackhouse et al. noted that although unforgiveness is scarcely studied, it remains largely theoretical, offering opportunities for empirical research [7]. While studies highlight forgiveness’s benefits for well-being, unforgiveness has been explored only recently [1, 9]. Singh et al. found that beyond its negative effects, unforgiveness has some positive outcomes for victims, such as improving self-esteem, and productivity, and reducing relationship boredom and re-victimization [1]. Unforgiveness helps individuals manage potential risks associated with forgiving offenders, providing a protective mechanism for victims.

Gender refers to male, female, or neutral states and includes social, psychological, and cultural meanings. Research has focused on gender’s role in shaping psychological traits, with evolutionary theory [10] and social role [11] dominating interpretations. Recently, researchers suggested examining gender differences as important indicators for understanding psychological characteristics [12, 13].

Research indicates gender differences in forgiveness [14], though it is unclear whether gender itself or another variable influences forgiveness. Methodological factors may also account for these differences [14]. While many studies have examined gender in various psychological domains, few have explored its role in unforgiveness. Some studies emphasize the need to investigate gender’s influence on unforgiveness [1, 9]. Unforgiveness may relate to dispositional traits, like emotional stability, sensitivity, agreeableness, empathy, and religiosity [2, 7], where gender differences are evident [15]. Research suggests unforgiveness involves complex emotions, like resentment and avoidance, not merely the absence of forgiveness, offering unique benefits, such as increased self-esteem and resilience. Gender differences in unforgiveness, shaped by socialization and cognitive processes, require further investigation for developing effective therapeutic interventions. Addressing unforgiveness in psychological research can enhance emotional well-being and support tailored conflict resolution strategies [3, 16].

Recent research links unforgiveness to anxiety, depression, stress, rumination, and emotional distress, exacerbating conflict and reducing life satisfaction [16, 17]. Forgiveness-based therapies show promise in improving emotional regulation and well-being [3]. Cultural factors, especially in collectivist societies, shape unforgiveness experiences [1, 18]. Thus, unforgiveness remains key to emotional healing interventions. Unforgiveness, characterized by persistent negative emotions, like resentment and hostility, varies by gender due to different socialization and emotional regulation strategies [7]. Qualitative research explores gender-specific experiences and nuances of unforgiveness beyond quantitative methods[1, 19], aiming to uncover cultural and psychological factors for tailored therapeutic interventions [14, 20].

A wealth of literature examines gender differences in psychological characteristics. However, researchers often focus on identifying these differences rather than understanding their nature. They either hypothesize about gender differences to validate or refute them or merely discuss observed differences. This approach is problematic, as it may cause researchers to overlook important aspects and dynamics of gender differences. Theories of gender differences in unforgiveness highlight distinct emotional and cognitive responses to conflict. Evolutionary perspectives indicate that women may exhibit greater leniency due to nurturing roles and social bonds, while men, motivated by dominance and competition, may forgive more readily [21]. Socialization theory suggests that women value relationship harmony, fostering forgiveness, whereas men emphasize independence [16, 22]. Cognitive models propose that men tend to ruminate less, enabling quicker resolution of grievances, while women, with stronger emotional attachments, may take longer to forgive [23]. Recent research supports these distinctions, acknowledging cultural influences on dynamics [14, 24]. Understanding these gender differences can challenge assumptions of uniform emotional responses, revealing nuanced dynamics, like rumination and emotional regulation, enriching psychological models, and enhancing forgiveness-based interventions [14, 20].

There are some problems related to the proof/disproval and/or discussion of the results obtained, including in the form of publication bias, which may prevent researchers from understanding the role of gender in the psychological abilities of the individual [13]. Unforgiveness is relatively a newer construct that has received less attention from researchers. Although recently it has become the focus of attention for some researchers [1, 7, 9], it is still an under-researched construct. This study aimed to examine gender differences in unforgiveness and to fill gaps in the literature that primarily focus on forgiveness or equate unforgiveness with its absence. By examining the unique emotional and cognitive processes of gender unforgiveness, this research will provide insights into how socialization and psychological factors influence these differences. This study will expand our understanding of unforgiveness and provide a nuanced perspective that can inform gender-sensitive therapeutic interventions and contribute to the development of more comprehensive psychological models.

Methods

Study design

The phenomenological framework was adopted as the guiding framework for the present study because a phenomenological inquiry views an individual’s lived experience as the starting point for investigation and meaning-making, helping the researcher to penetrate the individual’s life world. An inductive semantic thematic analysis using a realist approach [25, 26] was conducted by the authors.

Participants

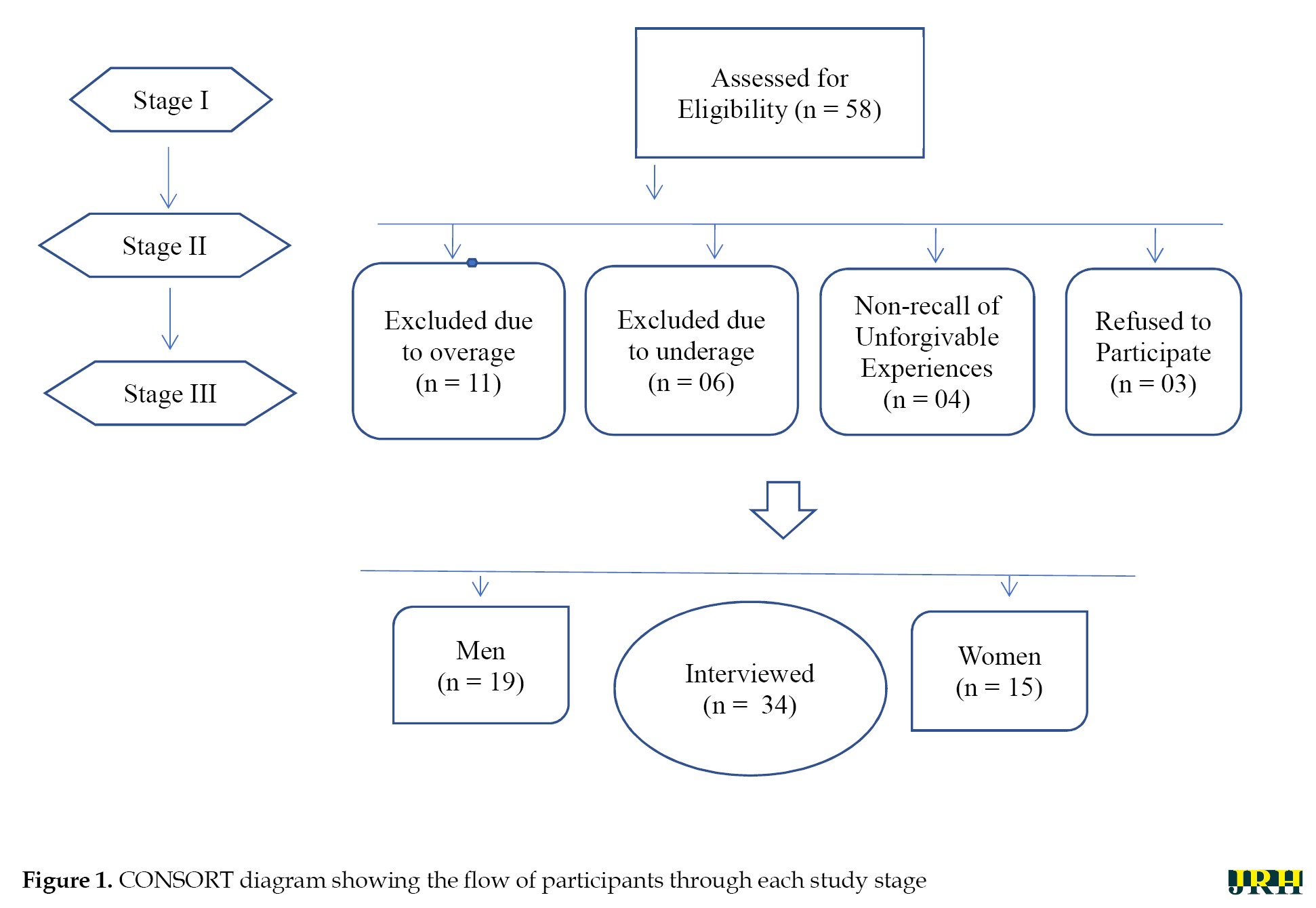

Participants were recruited through an advertisement containing study information and requirements. The advertisement was distributed online via social media, including Facebook, WhatsApp, Gmail, and LinkedIn, and in offline mode. A total of 58 university students from various academic departments of Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, 470003, Madhya Pradesh, India were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling in 2022. Purposive sampling targets specific characteristics, while snowball sampling recruits similar participants. These participants contacted the researcher, of whom 24 were excluded from the study: 11 because of being overage (over 40 years old), six because of being underage (under 20 years of age), four because they could not recall any unforgivable experience, and three because they refused to allow audio recordings of the interview content, and 34 participants were further interviewed. Figure 1 shows the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria of the study were as follows: participants who had experienced painful encounters in their lives that they were unable or unwilling to forgive, who were not suffering from any physical and/or mental illness, and who were between 20 and 40 years of age. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Age outside the range of 20 to 40 years, unwillingness to participate, reporting some physical and/or mental illness, and inability to recall unforgivable experiences.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview protocol was developed based on the unforgiveness literature [1, 7] and following the guidelines for qualitative research [27] aimed at uncovering the nature and dynamics of unforgiveness. The interview protocol was divided into three parts. Part A contained questions to provide information about the type of transgression and the perpetrator. Part B included questions on cognitive and affective dimensions of transgressions. Part C was prepared for participants who could not recall a transgression, in which they did not forgive the transgressor. This section is about imagining a transgression against them and answering some questions related to the transgression.

Ajit Kumar Singh conducted the interviews. Sixteen interviews were conducted over the phone and 22 in person. Before the interview began, the participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the interview, and their written consent was obtained. The interviews were conducted in Hindi. Follow-up questions and probing were also used where appropriate. The interviews were transcribed, anonymized, and checked for accuracy.

All participants were informed that their participation in the study was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. It was also informed that all data will be anonymized, and their confidentiality will be strictly maintained. The entire procedure was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee before conducting the study. The ethical review process involved the submission of research proposals to the institutional ethics committee, which evaluated risks, benefits, and participant welfare. Key considerations included informed consent, confidentiality, and potential harm. Adherence to ethical guidelines ensured participants were fully informed and protected, fostering trust and integrity in research. This process promoted accountability, ensuring that studies contribute positively to knowledge without compromising individual rights, thus enhancing the credibility and validity of the present research outcomes. The COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative data [28] and the guidelines for ensuring rigor and reflexivity in qualitative research [29] were also followed. To ensure the internal validity of the study, we used analyst triangulation [30]. Saturation occurred after 28 interviews. Six additional interviews were conducted to ensure data saturation, consistent with the literature [31].

Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic analysis [25, 32]. The thematic analysis involves six steps: Familiarization, coding, theme generation, theme review, theme definition, and writing up. Initially, the researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reading and re-reading transcripts. In vivo coding captured participants’ words, generating open codes that identified recurring ideas. These codes were grouped into broader themes, summarizing the essence of the data. The three authors independently generated subthemes and themes by sorting codes and resolving disagreements through conferencing. Themes were reviewed and refined to ensure accuracy, defined, and named to reflect differentiated understandings of the data in relation to the research questions, thereby contributing to the study’s overall interpretation and results [25].

In stage four, themes and subthemes were reviewed, and an expert panel of two researchers (one internal and one external) evaluated their suitability. Modifications were made based on their suggestions in phase five. In the sixth step, results were written following the guidelines [25]. Verbatim transcriptions were in Hindi, as participants spoke the language. The study data is available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) [33]. Data can be accessed through the OSF by visiting the OSF project page, where researchers have shared datasets, methods, and results.

Results

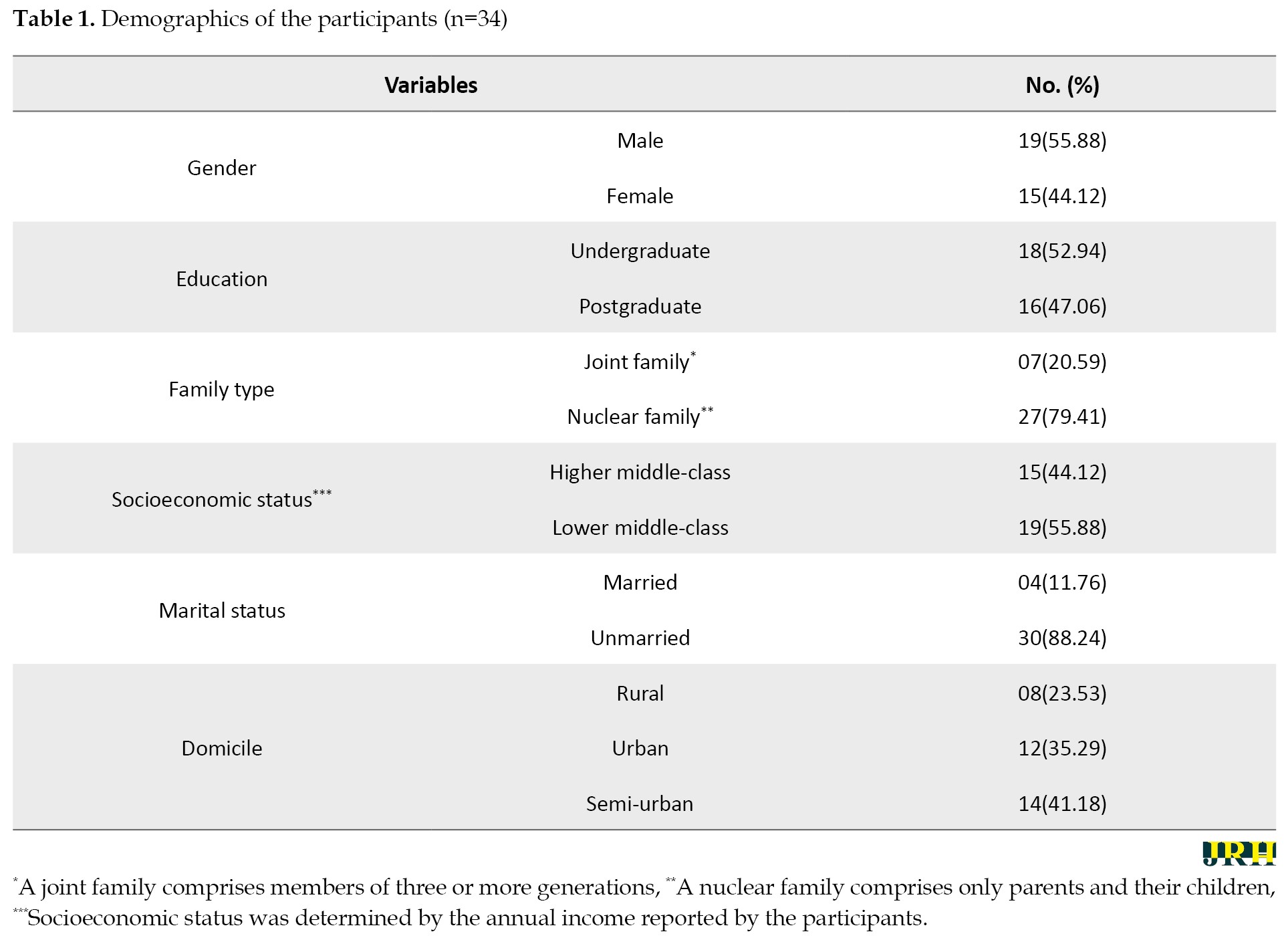

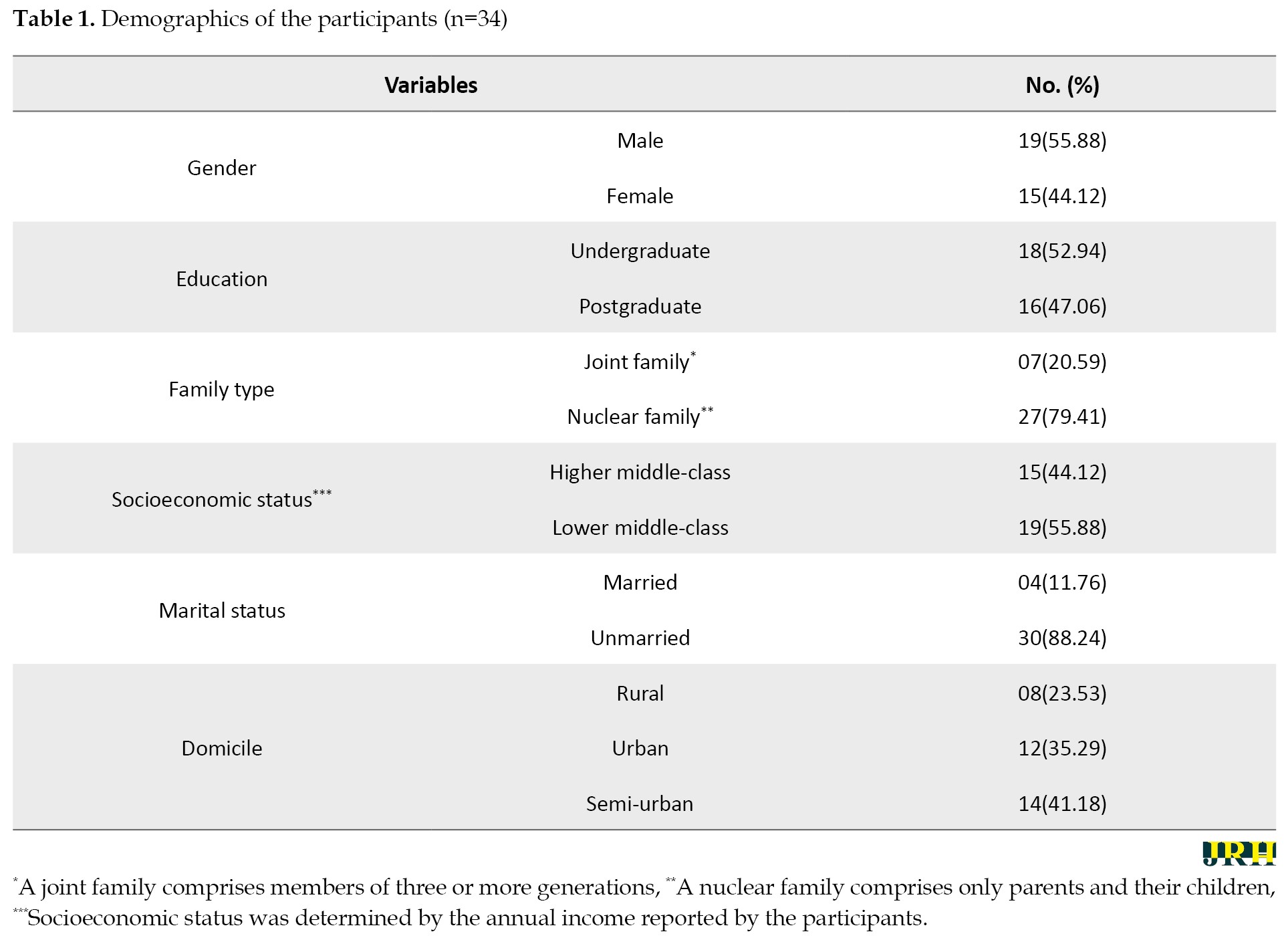

Thirty-four participants (age range=20-40 years, mean=26.43±2.88 years) were interviewed. Of these, 19 were males (age range=24-29 years, mean=27±2.24 years) and 15 were females (age range=22-32 years, mean=25.40±3.85 years). None of the participants were relatives, friends, or colleagues of any of the researchers. Biographical details are presented in Table 1.

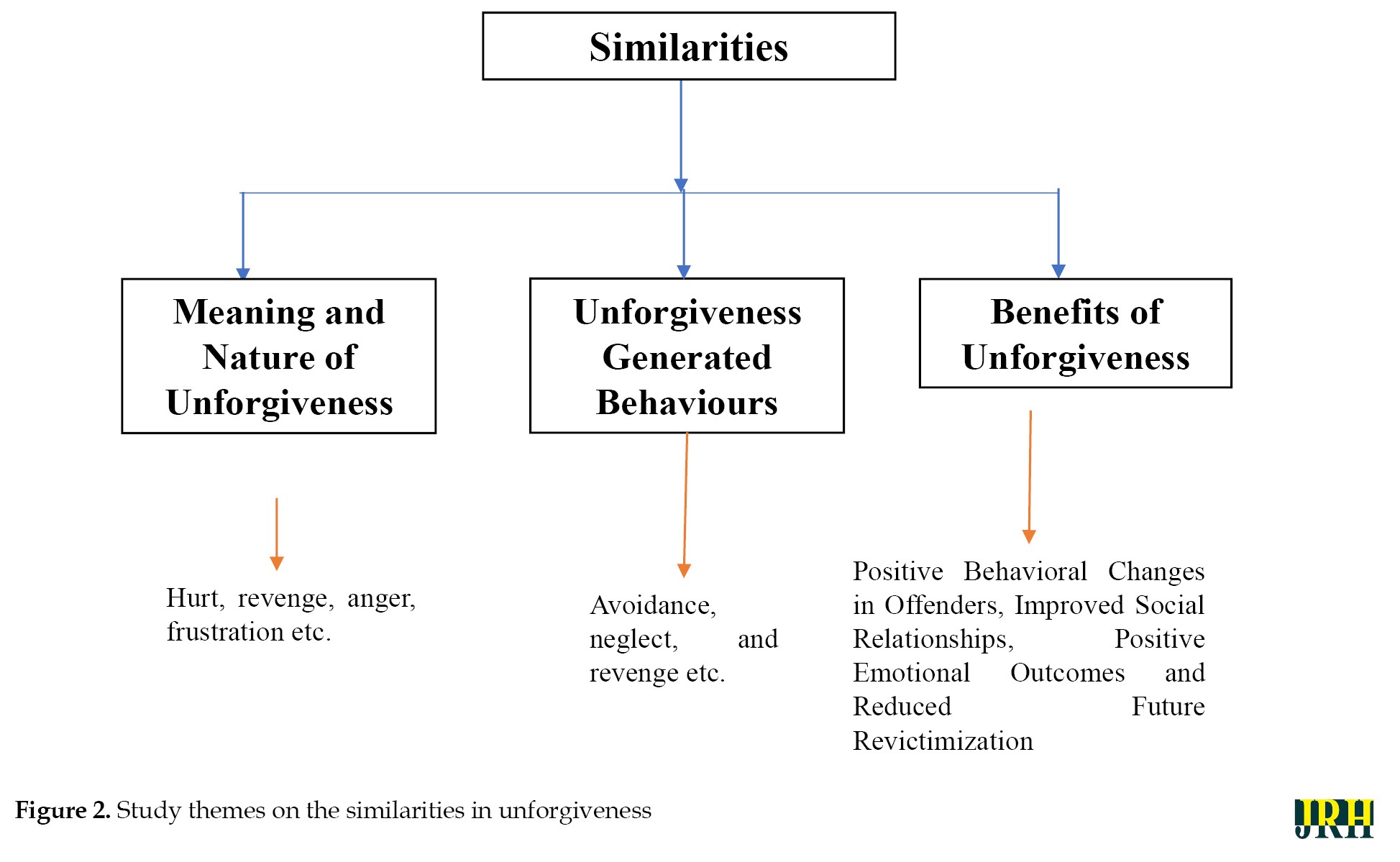

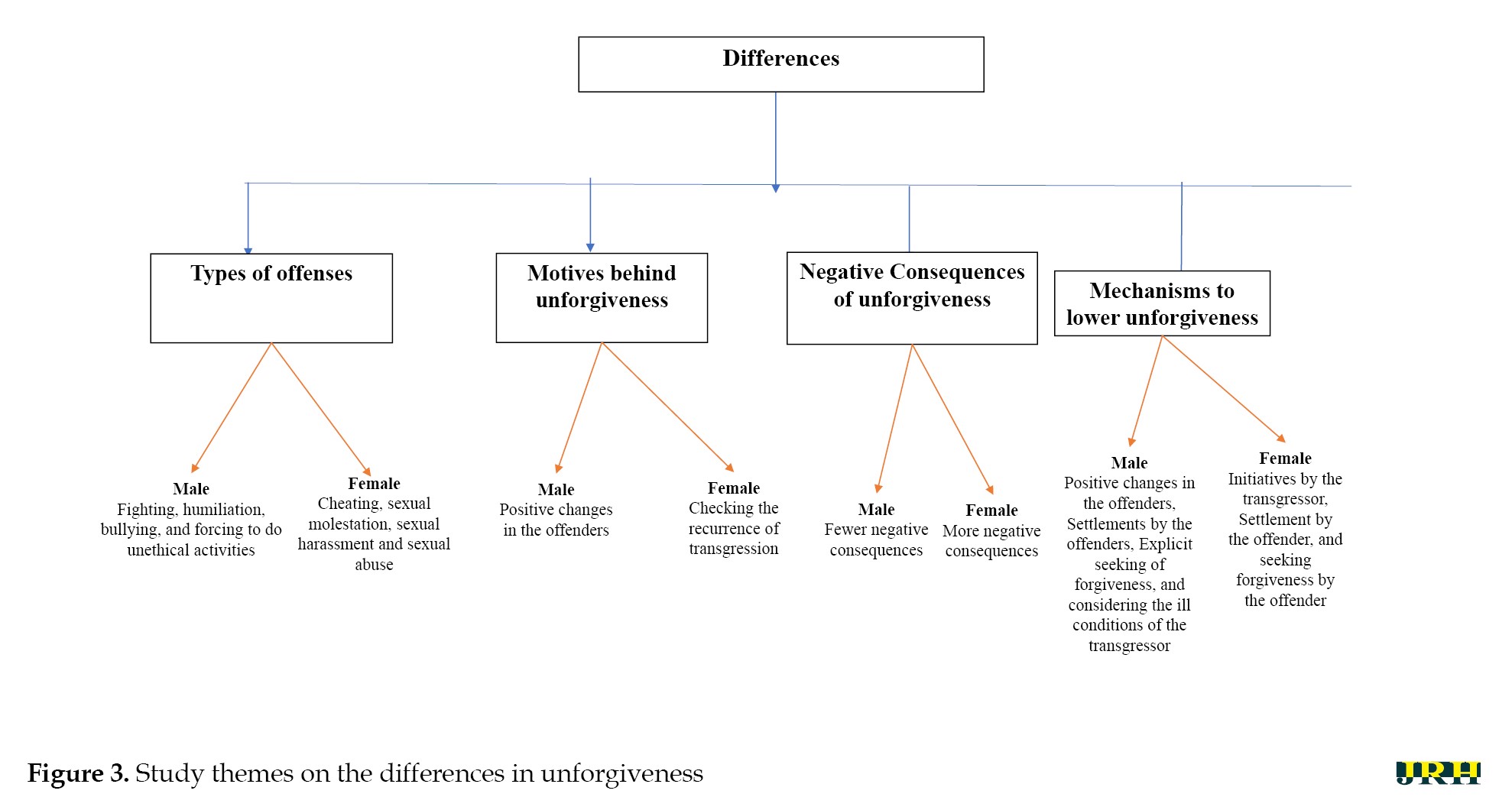

In the present study, we examined gender differences in unforgiveness using detailed, semi-structured interviews. Narratives of unforgivable experiences by men and women showed some similarities as well as differences in the nature and dynamics of unforgiveness. Men and women reported that, in many cases, they experienced different types of violations, some of which resulted in similar emotional and behavioral consequences, while others led to different outcomes (Figures 2 and 3).

Theme 1: Gender similarities in unforgiveness experiences

Male and female participants reported facing different types of transgressions, but interpretations of unforgiveness were found to be similar for both genders. They similarly described the importance of unforgiveness. A comparable trend was also observed in participants’ behaviors induced by transgressions. Both genders reported similar benefits associated with unforgiving behavior.

Subtheme 1: Meaning and nature of unforgiveness

Male and female participants were found to define unforgiveness in similar ways. Hurt, revenge, anger, and frustration were core features of their definition of unforgiveness. These were reflected in the following descriptions from the participants:

“When someone has hurt you and you can’t forget it, you think of revenge and develop feelings of hate and disgust” (Male [M]_6).

“Hatred, anger, and ignorance are the core characteristics of unforgiveness” (Female (F)_1).

Descriptions of participants’ unforgivable experiences revealed two types of unforgiveness: Active and passive unforgiveness. In active unforgiveness, they described being unable to forgive the perpetrators or forget the transgression(s). In the passive form of unforgiveness, they described forgiveness without forgetting. Participants of both genders described having forgiven the perpetrator but still harboring resentment and negative feelings. These styles of unforgiveness are evident in the following quotes:

“I have outwardly forgiven him, but it’s not the same as before. Apparently, I have forgiven him but have not forgotten the incident” (M_8).

“Things have changed, now I don’t talk to her like I used to. I talk to her and spend time with her, but I haven’t forgotten her” (F_3).

Both genders reported transgressions as equally hurtful and disturbing. This is reflected in the following quotes:

“What they did wasn’t a mistake; it was a transgression for me. So, there is no question of forgiving them” (M_2).

“My father manipulated his children and his wife for personal interests. He did not take responsibility for his family, never attended parent-teacher meetings, always kept us away from friends, completely isolated us from society, and harmed us”(F_13).

Subtheme 2: Unforgiveness-generated behaviours

There were many similarities between the unforgiveness-induced behaviors of male and female participants. For example, avoidance, neglect, and revenge were described by most participants as unforgiveness-induced behaviors of both genders. These appeared equally in the descriptions of male and female participants. Below are the representative quotes:

“This incident is not worth forgetting, but I avoid it” (M_14).

“I just want to feel like I never knew her. They are like strangers to me, even though they are in my Facebook and WhatsApp contact lists. I don’t care about you” (F_20).

Subtheme 3: Benefits of unforgiveness

The benefits associated with unforgiveness were reported equally by both groups. For example, positive behavioral changes in offenders have been described as resulting from unforgiveness, improved social relationships, and positive emotional outcomes, which were described equally by both genders. Both men and women reported that adhering to forgiveness can bring about positive change in offenders. The representative quotes that reflect these benefits of forgiveness are listed below:

“I learned that he is doing well in his life and has become a nice guy” (M_9).

“I don’t forgive him so he can do something good to restore the relationship” (F_7).

Holding to forgiveness has been described as improving personal and social relationships for both genders equally. They argued that unforgiveness can be a lesson for both others and the victims. Self-improvement and a sense of security in future relationships were other benefits reported equally by both genders. They were reflected in the following excerpts:

“My self-worth increased after this incident. Now I can take more time for myself. I’m happier now than before” (M_1).

“I notice a lot of changes in myself. I think before I trust people and I don’t get attached to anyone easily. I have started testing people and analyzing why they do what they do. I question whether what I’m doing is right or not, and I have begun to think about whom I should talk to and whom I shouldn’t” (F_16).

Reduced future revictimization was also cited as one of the benefits of unforgiveness among men and women. They were reflected in the following excerpts:

“If I don’t forgive him, I will put distance between us. This will help prevent the possibility of re-victimization” (M_26).

“If I forgive him, he may try to get back into the relationship, and I can’t take that risk” (F_5).

Theme 2: Gender differences in unforgiveness experiences

Aside from some similarities, there were some differences in the transgressions that men and women faced, which had different consequences for them. The motives for unforgiveness were also stated differently by the two groups.

Subtheme 1: Types of offenses

Reports of unforgivable experiences by men and women revealed different patterns of transgression for both genders, which led them to continue to forgive the perpetrator(s). Fighting, humiliation, bullying, and forcing unethical activities were described as unforgivable offenses by male participants, while cheating, sexual harassment, sexual harassment, and sexual abuse were described as unforgivable offenses by female participants. Arguments with friends and unethical behavior among seniors were described as unforgivable by male participants in the following quotes:

“When I played soccer, I was on the junior state team. My superiors forced me to take drugs, but I refused. They bullied me for it. I retaliated and hit them on the head. I still think about the incident and can never forgive them” (M_10).

In contrast, the types of transgressions described by female participants varied. For example, they identified various types of fraud, ignorance, and sexual harassment as the biggest transgressions, for which they still seek forgiveness. They are expressed in the following quotes:

“One of my good friends cheated on me. I came to know that she knows my Facebook ID and password and she posts many things on my Facebook and chats with someone with my name. She did all this because she took revenge on me, but I don’t know for what” (F_2).

“When I was in the 5th grade, I took part in tutoring during the holidays. There was a teacher who sexually harassed me for a few days. I didn’t realize much at the time, but I felt very bad. What he did was unforgettable” (F_17).

Subtheme 2: Motives behind unforgiveness

Both groups also differed in their motives for unforgiveness. Male participants reported that withholding forgiveness can bring about positive change in the offender. It appeared in the following excerpt:

“I haven’t forgiven him because I hope that I want to bring about a positive change in him” (M_29).

In contrast, most female participants reported that verifying the recurrence of transgressions was the primary motive for persisting in forgiveness. This could be due to the higher prevalence of insecurity among women. This was expressed in the following quotes:

“Just seeing this incident, I can forgive him. There have been many other instances in the past where he has wronged my father. Therefore, it is pointless to think about these things. I do not feel good” (F_22).

Subtheme 3: Consequences of unforgiveness

The two groups differed in their descriptions of the consequences of unforgiveness. The majority of male participants reported fewer negative consequences for not forgiving compared to their female counterparts. The following excerpts demonstrated the severity of the disorder due to the unforgiveness of the male participants:

“It doesn’t affect me anymore. I think it was part of life and I learned things” (M_11).

Female participants reported more negative consequences resulting from their unforgiving behavior compared to male participants.

“It was so painful for me at the time. Suicidal thoughts crossed my mind” (F_3).

“I was very scared then. I wasn’t brave enough to share it with others” (F_17).

Both genders differed in their descriptions of rumination. Male participants experienced less or no rumination about the transgression compared to female participants. This was reflected in the following quotes:

“I don’t remember this event in my daily life” (M_13).

“I can’t forget this incident. It still bothers me” (F_25).

The study highlights both similarities and differences in unforgiveness experiences between genders. Men and women commonly defined unforgiveness through emotions, like anger and revenge, but the nature of transgressions differed. Men reported bullying and humiliation, while women emphasized cheating and sexual harassment, revealing distinct emotional landscapes. Both genders experienced negative outcomes, though women reported higher emotional distress and rumination. These findings align with research on gendered emotional responses, stressing the need for gender-sensitive approaches in therapeutic practices (M_9; F_7). Behavioral responses, such as avoidance and neglect, were common in both genders: “I avoid it” (M_14) and “I just want to feel like I never knew her” (F_20). Unforgiveness also revealed shared emotions—hurt, anger, and frustration—with a male participant stating, “I developed feelings of hate and disgust,” similar to a female participant’s view: “Hatred, anger, and ignorance are the core of unforgiveness” (M_14; F_20). Motivations differed, with men withholding forgiveness to effect positive change and women focusing on preventing future harm (M_9; F_7). Women faced more intense emotional consequences, including suicidal thoughts and fear, compared to men who often dismissed transgressions as part of life. These findings demonstrate the complexity and gendered dimensions of unforgiveness.

The study explored gender differences in unforgiveness. Both men and women experienced anger and revenge, but men cited bullying and humiliation, while women highlighted cheating and harassment. Women reported greater emotional distress and rumination. While both genders showed avoidance behaviors, men viewed unforgiveness as promoting change, whereas women focused on preventing harm, revealing distinct emotional landscapes and motivations.

Discussion

The present study revealed significant gender differences in the experience and expression of unforgiveness. Both men and women reported feelings of revenge, anger, and frustration as core components of unforgiveness. However, variations emerged in the types of offenses considered unforgivable and their underlying motives. Women often cited the prevention of future offenses as a primary reason for their unforgiveness, while men focused on the need for positive behavioral changes in the offender. Additionally, female participants reported more negative consequences from unforgiveness compared to males. The analysis highlighted both similarities and differences in men’s and women’s experiences with unforgiveness, which influenced their willingness to forgive or withhold forgiveness after transgressions. Ultimately, the willingness to grant forgiveness depended on the nature and severity of the offense.

Unforgiveness occurs when a person consciously harbors negative feelings toward the transgressor, as reflected in the descriptions of nearly all study participants. Male and female participants shared similar experiences related to unforgiveness, both describing it as involving feelings of revenge, anger, and frustration. Previous research indicates that unforgiveness is linked to negative emotions that lead to rumination [2, 7] and result in adverse personal and interpersonal consequences [1]. Some studies also demonstrate that people may grant forgiveness selectively based on the relationship type and the transgression’s severity [34].

Similarities in the unforgiveness-induced behaviors of men and women were evident, with most participants describing avoidance, neglect, and revenge as behaviors resulting from unforgiveness. Previous research supports these findings, noting that individuals often avoid those who have wronged them [35, 36]. This violator avoidance aligns with Skinner’s operant conditioning theory [37], which states that behaviors are more likely to occur when reinforced. Both genders equally reported revenge as a consequence of unforgiveness, expressing that feelings of revenge led them to harbor negative emotions toward the transgressor, which is corroborated by previous studies [7, 38].

Positive changes in offender behavior due to unforgiveness, improved social relationships, and positive emotional outcomes were described by both genders. Both men and women reported that adhering to forgiveness can bring about positive changes in offenders, improve personal and social relationships, and reduce future revictimization by setting a role model for both the offender and others. Self-improvement and a sense of security in future relationships were equally described as benefits of unforgiveness by both genders. These results were also reflected in some previous studies [1, 7, 9, 39].

While there are some similarities in the experience and expression of unforgiveness between men and women, notable differences exist. Men and women differ in the types of offenses they encounter and their motives for unforgiveness. The consequences of unforgiveness are also reported differently by both genders. Male and female participants exhibited distinct transgression patterns influencing their decisions to forgive offenders. Male participants identified fighting, humiliation, bullying, and coercing unethical activities as unforgivable offenses, while female participants cited cheating, sexual harassment, and sexual abuse as unforgivable. These findings relate to previous research indicating that women are more likely to experience sexual transgressions, leading to insecurities and unforgiveness [39]. The study’s findings align with earlier research on emotional responses and forgiveness processes. Both men and women experienced unforgiveness through negative emotions, like revenge and anger, confirming that unforgiveness can result in rumination and negative social consequences [1]. However, this study emphasizes specific gendered motives and consequences of unforgiveness, showing that female participants aimed to prevent re-offending, while male participants focused on altering offenders’ behavior [40]. Tsirigotis also discussed gender-specific transgressions, like sexual offenses committed by women [41]. This extends the literature by highlighting the complexity of unforgiveness experiences and their potential adaptive functions in specific contexts [39].

Both groups differed in their motives for unforgiveness. Female participants cited unforgiveness as a means to reduce the recurrence of offending behavior, while males emphasized the necessity of positive change in the offender’s behavior. This indicates possible differences in how men and women perceive transgressions, potentially linked to evolutionary perspectives on emotions [42]. The consequences of unforgiveness were also perceived differently, with female participants reporting more negative outcomes than their male counterparts. This discrepancy may stem from variations in how each gender ruminates on negative emotions related to transgressions. Research suggests that females tend to engage with negative emotions more than males [43], which may contribute to a greater likelihood of holding on to unforgiveness among females compared to males.

The findings indicated that while both genders experience similar emotions related to unforgiveness—such as revenge, anger, and frustration—the underlying motives and consequences differ significantly. Male participants often viewed unforgiveness as a catalyst for inducing a change in the offender, while females were more inclined to prevent the recurrence of harmful behavior. These results align with existing research, which highlights the relationship between unforgiveness and negative emotions [2, 7]. However, the distinct emotional processing styles identified, particularly the greater tendency for females to ruminate on negative emotions [43], suggest a nuanced understanding of unforgiveness across genders. This understanding can inform therapeutic interventions tailored to gender-specific emotional dynamics and coping strategies, recognizing that unforgiveness can have adaptive functions in certain contexts.

The present study offers valuable insights into the unforgiveness literature by examining gender differences, an aspect previously overlooked. It highlights that unforgiveness is an internal state shaped by various psychological processes. Findings revealed both similarities and differences between men and women regarding their experiences and expressions of unforgiveness. Participants indicated that withholding forgiveness often felt beneficial. Gender differences in socialization practices, expectations, life goals, and personal values may significantly influence these differences in unforgiveness. While understanding gender differences in psychological phenomena has long been a focus, it is essential to delve into how these differences manifest in experiences and expressions of psychological constructs. This understanding can guide researchers and practitioners in tailoring interventions for men and women, acknowledging their distinct experiences and potential needs for different coping strategies, as evidenced by the results of the current study.

Researchers should recognize that unforgiveness is sometimes appropriate or necessary, as forgiving the offender may jeopardize personal and social relationships. Unforgiveness is not always undesirable; it can be adaptive. Understanding these distinctions allows individuals to reflect on whether forgiveness is suitable or not. Studying unforgiveness has significant implications, particularly for therapeutic, counseling, and psychoeducational interventions. A better grasp of unforgiveness can help practitioners address negative cognition and emotionality, preventing maladaptive behavior patterns. In some situations, forgiving the offender can lead to negative consequences, such as repeated offenses or immoral behavior. However, maintaining unforgiveness may enhance security, self-esteem, and defense of moral principles. Therefore, carefully considering when to forgive is essential for practitioners working with clients in various settings.

Understanding gender differences in unforgiveness can inform interventions by tailoring therapeutic approaches to the specific needs of men and women. For women linking unforgiveness to past transgressions, like sexual harassment, therapy may focus on trauma-informed care, emphasizing emotional expression and coping strategies to counteract ruminations and negative emotions. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can assist women in reframing their thoughts about unforgiveness and developing healthier coping mechanisms [1]. Men, who often see unforgiveness as a means to elicit change in offenders, may benefit from assertiveness training and behavior change strategies. Integrative approaches combining narrative therapy to reconstruct experiences may also be useful [7, 14]. Recognizing these gender dynamics can enhance therapeutic effectiveness and promote healthier emotional processing. The study’s strengths include being the first to examine gender differences in unforgiveness and one of the few using qualitative methods to explore this under-researched construct. It utilized in-depth semi-structured interviews with participants who experienced transgressions, offering personal insights.

Conclusion

The current study explored gender differences in unforgiveness, revealing gaps in existing literature and emphasizing gender’s role in its expression and experience. The findings hold clinical significance, suggesting that practitioners acknowledge unforgiveness’s adaptive functions, especially when forgiveness might jeopardize personal safety or well-being. Gender-specific interventions are crucial, as men and women have different motives, experiences, and expressions of unforgiveness. Therapeutic approaches should target these differences, aiding clients in managing negative emotions and preventing maladaptive behaviors.

Limitations and future directions

The study has several limitations that may affect the generalizability of its findings. It may not adequately address cultural variations in unforgiveness, as cultural norms significantly shape emotional responses and interpersonal dynamics, making findings from one context less applicable to diverse populations. Additionally, the sample may lack a broad age range, potentially skewing results, as younger and older adults might experience unforgiveness differently due to generational differences in socialization and emotional processing. Relying on interview data may introduce biases, as participants might not fully express their feelings or could be influenced by social desirability. The qualitative nature of the research may also limit broad conclusions, as findings are often context-specific. These limitations warrant caution in interpreting results and applying them universally. Future research should explore gender differences in unforgiveness and the psychological processes that influence forgiveness decisions to enhance therapeutic interventions and better understand its adaptive functions in various relationships.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, India (Approval No.: DHSGV/IEC/2022/04).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Inforgiveness is defined as a cold emotion involving resentment, bitterness, and motivated avoidance or retribution toward a transgressor [1, 2]. It is a conscious state, in which individuals harbor negative feelings toward the perpetrator. Research on unforgiveness has been relatively sparse, with many researchers describing it simply as the opposite of forgiveness [3]. It is often measured through the inventory of interpersonal motivations related to transgressions [4], levels of resentment toward the transgressor [5], or by reversing forgiveness measures [6]. Unforgiveness is distinct from general hostility or the mere absence of forgiveness, as it reflects persistent negative emotions and motivation to retaliate or avoid the transgressor. This emotional state is associated with interpersonal conflict and emotional distress, with personality traits and gender influencing its manifestation [1, 7].

Unforgiveness, often defined as resentment, bitterness, and avoidance or retribution, is measured using tools, like the transgression-related interpersonal motivations inventory (TRIM) and reversed forgiveness scales [8]. However, these approaches tend to simplify unforgiveness as the opposite of forgiveness, overlooking its emotional complexity. Self-reports on resentment and negative emotions are also used, but they may miss key cognitive and behavioral dimensions. Research typically frames unforgiveness as merely the absence of forgiveness, limiting a deeper understanding of its distinct effects. Unforgiveness, involving emotions, like bitterness, can have protective functions beyond its negative impact. A more nuanced approach is needed to explore how unforgiveness may contribute to emotional resilience and protect individuals from harm in relational dynamics [7].

Stackhouse et al. noted that although unforgiveness is scarcely studied, it remains largely theoretical, offering opportunities for empirical research [7]. While studies highlight forgiveness’s benefits for well-being, unforgiveness has been explored only recently [1, 9]. Singh et al. found that beyond its negative effects, unforgiveness has some positive outcomes for victims, such as improving self-esteem, and productivity, and reducing relationship boredom and re-victimization [1]. Unforgiveness helps individuals manage potential risks associated with forgiving offenders, providing a protective mechanism for victims.

Gender refers to male, female, or neutral states and includes social, psychological, and cultural meanings. Research has focused on gender’s role in shaping psychological traits, with evolutionary theory [10] and social role [11] dominating interpretations. Recently, researchers suggested examining gender differences as important indicators for understanding psychological characteristics [12, 13].

Research indicates gender differences in forgiveness [14], though it is unclear whether gender itself or another variable influences forgiveness. Methodological factors may also account for these differences [14]. While many studies have examined gender in various psychological domains, few have explored its role in unforgiveness. Some studies emphasize the need to investigate gender’s influence on unforgiveness [1, 9]. Unforgiveness may relate to dispositional traits, like emotional stability, sensitivity, agreeableness, empathy, and religiosity [2, 7], where gender differences are evident [15]. Research suggests unforgiveness involves complex emotions, like resentment and avoidance, not merely the absence of forgiveness, offering unique benefits, such as increased self-esteem and resilience. Gender differences in unforgiveness, shaped by socialization and cognitive processes, require further investigation for developing effective therapeutic interventions. Addressing unforgiveness in psychological research can enhance emotional well-being and support tailored conflict resolution strategies [3, 16].

Recent research links unforgiveness to anxiety, depression, stress, rumination, and emotional distress, exacerbating conflict and reducing life satisfaction [16, 17]. Forgiveness-based therapies show promise in improving emotional regulation and well-being [3]. Cultural factors, especially in collectivist societies, shape unforgiveness experiences [1, 18]. Thus, unforgiveness remains key to emotional healing interventions. Unforgiveness, characterized by persistent negative emotions, like resentment and hostility, varies by gender due to different socialization and emotional regulation strategies [7]. Qualitative research explores gender-specific experiences and nuances of unforgiveness beyond quantitative methods[1, 19], aiming to uncover cultural and psychological factors for tailored therapeutic interventions [14, 20].

A wealth of literature examines gender differences in psychological characteristics. However, researchers often focus on identifying these differences rather than understanding their nature. They either hypothesize about gender differences to validate or refute them or merely discuss observed differences. This approach is problematic, as it may cause researchers to overlook important aspects and dynamics of gender differences. Theories of gender differences in unforgiveness highlight distinct emotional and cognitive responses to conflict. Evolutionary perspectives indicate that women may exhibit greater leniency due to nurturing roles and social bonds, while men, motivated by dominance and competition, may forgive more readily [21]. Socialization theory suggests that women value relationship harmony, fostering forgiveness, whereas men emphasize independence [16, 22]. Cognitive models propose that men tend to ruminate less, enabling quicker resolution of grievances, while women, with stronger emotional attachments, may take longer to forgive [23]. Recent research supports these distinctions, acknowledging cultural influences on dynamics [14, 24]. Understanding these gender differences can challenge assumptions of uniform emotional responses, revealing nuanced dynamics, like rumination and emotional regulation, enriching psychological models, and enhancing forgiveness-based interventions [14, 20].

There are some problems related to the proof/disproval and/or discussion of the results obtained, including in the form of publication bias, which may prevent researchers from understanding the role of gender in the psychological abilities of the individual [13]. Unforgiveness is relatively a newer construct that has received less attention from researchers. Although recently it has become the focus of attention for some researchers [1, 7, 9], it is still an under-researched construct. This study aimed to examine gender differences in unforgiveness and to fill gaps in the literature that primarily focus on forgiveness or equate unforgiveness with its absence. By examining the unique emotional and cognitive processes of gender unforgiveness, this research will provide insights into how socialization and psychological factors influence these differences. This study will expand our understanding of unforgiveness and provide a nuanced perspective that can inform gender-sensitive therapeutic interventions and contribute to the development of more comprehensive psychological models.

Methods

Study design

The phenomenological framework was adopted as the guiding framework for the present study because a phenomenological inquiry views an individual’s lived experience as the starting point for investigation and meaning-making, helping the researcher to penetrate the individual’s life world. An inductive semantic thematic analysis using a realist approach [25, 26] was conducted by the authors.

Participants

Participants were recruited through an advertisement containing study information and requirements. The advertisement was distributed online via social media, including Facebook, WhatsApp, Gmail, and LinkedIn, and in offline mode. A total of 58 university students from various academic departments of Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, 470003, Madhya Pradesh, India were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling in 2022. Purposive sampling targets specific characteristics, while snowball sampling recruits similar participants. These participants contacted the researcher, of whom 24 were excluded from the study: 11 because of being overage (over 40 years old), six because of being underage (under 20 years of age), four because they could not recall any unforgivable experience, and three because they refused to allow audio recordings of the interview content, and 34 participants were further interviewed. Figure 1 shows the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria of the study were as follows: participants who had experienced painful encounters in their lives that they were unable or unwilling to forgive, who were not suffering from any physical and/or mental illness, and who were between 20 and 40 years of age. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Age outside the range of 20 to 40 years, unwillingness to participate, reporting some physical and/or mental illness, and inability to recall unforgivable experiences.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview protocol was developed based on the unforgiveness literature [1, 7] and following the guidelines for qualitative research [27] aimed at uncovering the nature and dynamics of unforgiveness. The interview protocol was divided into three parts. Part A contained questions to provide information about the type of transgression and the perpetrator. Part B included questions on cognitive and affective dimensions of transgressions. Part C was prepared for participants who could not recall a transgression, in which they did not forgive the transgressor. This section is about imagining a transgression against them and answering some questions related to the transgression.

Ajit Kumar Singh conducted the interviews. Sixteen interviews were conducted over the phone and 22 in person. Before the interview began, the participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the interview, and their written consent was obtained. The interviews were conducted in Hindi. Follow-up questions and probing were also used where appropriate. The interviews were transcribed, anonymized, and checked for accuracy.

All participants were informed that their participation in the study was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. It was also informed that all data will be anonymized, and their confidentiality will be strictly maintained. The entire procedure was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee before conducting the study. The ethical review process involved the submission of research proposals to the institutional ethics committee, which evaluated risks, benefits, and participant welfare. Key considerations included informed consent, confidentiality, and potential harm. Adherence to ethical guidelines ensured participants were fully informed and protected, fostering trust and integrity in research. This process promoted accountability, ensuring that studies contribute positively to knowledge without compromising individual rights, thus enhancing the credibility and validity of the present research outcomes. The COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative data [28] and the guidelines for ensuring rigor and reflexivity in qualitative research [29] were also followed. To ensure the internal validity of the study, we used analyst triangulation [30]. Saturation occurred after 28 interviews. Six additional interviews were conducted to ensure data saturation, consistent with the literature [31].

Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic analysis [25, 32]. The thematic analysis involves six steps: Familiarization, coding, theme generation, theme review, theme definition, and writing up. Initially, the researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reading and re-reading transcripts. In vivo coding captured participants’ words, generating open codes that identified recurring ideas. These codes were grouped into broader themes, summarizing the essence of the data. The three authors independently generated subthemes and themes by sorting codes and resolving disagreements through conferencing. Themes were reviewed and refined to ensure accuracy, defined, and named to reflect differentiated understandings of the data in relation to the research questions, thereby contributing to the study’s overall interpretation and results [25].

In stage four, themes and subthemes were reviewed, and an expert panel of two researchers (one internal and one external) evaluated their suitability. Modifications were made based on their suggestions in phase five. In the sixth step, results were written following the guidelines [25]. Verbatim transcriptions were in Hindi, as participants spoke the language. The study data is available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) [33]. Data can be accessed through the OSF by visiting the OSF project page, where researchers have shared datasets, methods, and results.

Results

Thirty-four participants (age range=20-40 years, mean=26.43±2.88 years) were interviewed. Of these, 19 were males (age range=24-29 years, mean=27±2.24 years) and 15 were females (age range=22-32 years, mean=25.40±3.85 years). None of the participants were relatives, friends, or colleagues of any of the researchers. Biographical details are presented in Table 1.

In the present study, we examined gender differences in unforgiveness using detailed, semi-structured interviews. Narratives of unforgivable experiences by men and women showed some similarities as well as differences in the nature and dynamics of unforgiveness. Men and women reported that, in many cases, they experienced different types of violations, some of which resulted in similar emotional and behavioral consequences, while others led to different outcomes (Figures 2 and 3).

Theme 1: Gender similarities in unforgiveness experiences

Male and female participants reported facing different types of transgressions, but interpretations of unforgiveness were found to be similar for both genders. They similarly described the importance of unforgiveness. A comparable trend was also observed in participants’ behaviors induced by transgressions. Both genders reported similar benefits associated with unforgiving behavior.

Subtheme 1: Meaning and nature of unforgiveness

Male and female participants were found to define unforgiveness in similar ways. Hurt, revenge, anger, and frustration were core features of their definition of unforgiveness. These were reflected in the following descriptions from the participants:

“When someone has hurt you and you can’t forget it, you think of revenge and develop feelings of hate and disgust” (Male [M]_6).

“Hatred, anger, and ignorance are the core characteristics of unforgiveness” (Female (F)_1).

Descriptions of participants’ unforgivable experiences revealed two types of unforgiveness: Active and passive unforgiveness. In active unforgiveness, they described being unable to forgive the perpetrators or forget the transgression(s). In the passive form of unforgiveness, they described forgiveness without forgetting. Participants of both genders described having forgiven the perpetrator but still harboring resentment and negative feelings. These styles of unforgiveness are evident in the following quotes:

“I have outwardly forgiven him, but it’s not the same as before. Apparently, I have forgiven him but have not forgotten the incident” (M_8).

“Things have changed, now I don’t talk to her like I used to. I talk to her and spend time with her, but I haven’t forgotten her” (F_3).

Both genders reported transgressions as equally hurtful and disturbing. This is reflected in the following quotes:

“What they did wasn’t a mistake; it was a transgression for me. So, there is no question of forgiving them” (M_2).

“My father manipulated his children and his wife for personal interests. He did not take responsibility for his family, never attended parent-teacher meetings, always kept us away from friends, completely isolated us from society, and harmed us”(F_13).

Subtheme 2: Unforgiveness-generated behaviours

There were many similarities between the unforgiveness-induced behaviors of male and female participants. For example, avoidance, neglect, and revenge were described by most participants as unforgiveness-induced behaviors of both genders. These appeared equally in the descriptions of male and female participants. Below are the representative quotes:

“This incident is not worth forgetting, but I avoid it” (M_14).

“I just want to feel like I never knew her. They are like strangers to me, even though they are in my Facebook and WhatsApp contact lists. I don’t care about you” (F_20).

Subtheme 3: Benefits of unforgiveness

The benefits associated with unforgiveness were reported equally by both groups. For example, positive behavioral changes in offenders have been described as resulting from unforgiveness, improved social relationships, and positive emotional outcomes, which were described equally by both genders. Both men and women reported that adhering to forgiveness can bring about positive change in offenders. The representative quotes that reflect these benefits of forgiveness are listed below:

“I learned that he is doing well in his life and has become a nice guy” (M_9).

“I don’t forgive him so he can do something good to restore the relationship” (F_7).

Holding to forgiveness has been described as improving personal and social relationships for both genders equally. They argued that unforgiveness can be a lesson for both others and the victims. Self-improvement and a sense of security in future relationships were other benefits reported equally by both genders. They were reflected in the following excerpts:

“My self-worth increased after this incident. Now I can take more time for myself. I’m happier now than before” (M_1).

“I notice a lot of changes in myself. I think before I trust people and I don’t get attached to anyone easily. I have started testing people and analyzing why they do what they do. I question whether what I’m doing is right or not, and I have begun to think about whom I should talk to and whom I shouldn’t” (F_16).

Reduced future revictimization was also cited as one of the benefits of unforgiveness among men and women. They were reflected in the following excerpts:

“If I don’t forgive him, I will put distance between us. This will help prevent the possibility of re-victimization” (M_26).

“If I forgive him, he may try to get back into the relationship, and I can’t take that risk” (F_5).

Theme 2: Gender differences in unforgiveness experiences

Aside from some similarities, there were some differences in the transgressions that men and women faced, which had different consequences for them. The motives for unforgiveness were also stated differently by the two groups.

Subtheme 1: Types of offenses

Reports of unforgivable experiences by men and women revealed different patterns of transgression for both genders, which led them to continue to forgive the perpetrator(s). Fighting, humiliation, bullying, and forcing unethical activities were described as unforgivable offenses by male participants, while cheating, sexual harassment, sexual harassment, and sexual abuse were described as unforgivable offenses by female participants. Arguments with friends and unethical behavior among seniors were described as unforgivable by male participants in the following quotes:

“When I played soccer, I was on the junior state team. My superiors forced me to take drugs, but I refused. They bullied me for it. I retaliated and hit them on the head. I still think about the incident and can never forgive them” (M_10).

In contrast, the types of transgressions described by female participants varied. For example, they identified various types of fraud, ignorance, and sexual harassment as the biggest transgressions, for which they still seek forgiveness. They are expressed in the following quotes:

“One of my good friends cheated on me. I came to know that she knows my Facebook ID and password and she posts many things on my Facebook and chats with someone with my name. She did all this because she took revenge on me, but I don’t know for what” (F_2).

“When I was in the 5th grade, I took part in tutoring during the holidays. There was a teacher who sexually harassed me for a few days. I didn’t realize much at the time, but I felt very bad. What he did was unforgettable” (F_17).

Subtheme 2: Motives behind unforgiveness

Both groups also differed in their motives for unforgiveness. Male participants reported that withholding forgiveness can bring about positive change in the offender. It appeared in the following excerpt:

“I haven’t forgiven him because I hope that I want to bring about a positive change in him” (M_29).

In contrast, most female participants reported that verifying the recurrence of transgressions was the primary motive for persisting in forgiveness. This could be due to the higher prevalence of insecurity among women. This was expressed in the following quotes:

“Just seeing this incident, I can forgive him. There have been many other instances in the past where he has wronged my father. Therefore, it is pointless to think about these things. I do not feel good” (F_22).

Subtheme 3: Consequences of unforgiveness

The two groups differed in their descriptions of the consequences of unforgiveness. The majority of male participants reported fewer negative consequences for not forgiving compared to their female counterparts. The following excerpts demonstrated the severity of the disorder due to the unforgiveness of the male participants:

“It doesn’t affect me anymore. I think it was part of life and I learned things” (M_11).

Female participants reported more negative consequences resulting from their unforgiving behavior compared to male participants.

“It was so painful for me at the time. Suicidal thoughts crossed my mind” (F_3).

“I was very scared then. I wasn’t brave enough to share it with others” (F_17).

Both genders differed in their descriptions of rumination. Male participants experienced less or no rumination about the transgression compared to female participants. This was reflected in the following quotes:

“I don’t remember this event in my daily life” (M_13).

“I can’t forget this incident. It still bothers me” (F_25).

The study highlights both similarities and differences in unforgiveness experiences between genders. Men and women commonly defined unforgiveness through emotions, like anger and revenge, but the nature of transgressions differed. Men reported bullying and humiliation, while women emphasized cheating and sexual harassment, revealing distinct emotional landscapes. Both genders experienced negative outcomes, though women reported higher emotional distress and rumination. These findings align with research on gendered emotional responses, stressing the need for gender-sensitive approaches in therapeutic practices (M_9; F_7). Behavioral responses, such as avoidance and neglect, were common in both genders: “I avoid it” (M_14) and “I just want to feel like I never knew her” (F_20). Unforgiveness also revealed shared emotions—hurt, anger, and frustration—with a male participant stating, “I developed feelings of hate and disgust,” similar to a female participant’s view: “Hatred, anger, and ignorance are the core of unforgiveness” (M_14; F_20). Motivations differed, with men withholding forgiveness to effect positive change and women focusing on preventing future harm (M_9; F_7). Women faced more intense emotional consequences, including suicidal thoughts and fear, compared to men who often dismissed transgressions as part of life. These findings demonstrate the complexity and gendered dimensions of unforgiveness.

The study explored gender differences in unforgiveness. Both men and women experienced anger and revenge, but men cited bullying and humiliation, while women highlighted cheating and harassment. Women reported greater emotional distress and rumination. While both genders showed avoidance behaviors, men viewed unforgiveness as promoting change, whereas women focused on preventing harm, revealing distinct emotional landscapes and motivations.

Discussion

The present study revealed significant gender differences in the experience and expression of unforgiveness. Both men and women reported feelings of revenge, anger, and frustration as core components of unforgiveness. However, variations emerged in the types of offenses considered unforgivable and their underlying motives. Women often cited the prevention of future offenses as a primary reason for their unforgiveness, while men focused on the need for positive behavioral changes in the offender. Additionally, female participants reported more negative consequences from unforgiveness compared to males. The analysis highlighted both similarities and differences in men’s and women’s experiences with unforgiveness, which influenced their willingness to forgive or withhold forgiveness after transgressions. Ultimately, the willingness to grant forgiveness depended on the nature and severity of the offense.

Unforgiveness occurs when a person consciously harbors negative feelings toward the transgressor, as reflected in the descriptions of nearly all study participants. Male and female participants shared similar experiences related to unforgiveness, both describing it as involving feelings of revenge, anger, and frustration. Previous research indicates that unforgiveness is linked to negative emotions that lead to rumination [2, 7] and result in adverse personal and interpersonal consequences [1]. Some studies also demonstrate that people may grant forgiveness selectively based on the relationship type and the transgression’s severity [34].

Similarities in the unforgiveness-induced behaviors of men and women were evident, with most participants describing avoidance, neglect, and revenge as behaviors resulting from unforgiveness. Previous research supports these findings, noting that individuals often avoid those who have wronged them [35, 36]. This violator avoidance aligns with Skinner’s operant conditioning theory [37], which states that behaviors are more likely to occur when reinforced. Both genders equally reported revenge as a consequence of unforgiveness, expressing that feelings of revenge led them to harbor negative emotions toward the transgressor, which is corroborated by previous studies [7, 38].

Positive changes in offender behavior due to unforgiveness, improved social relationships, and positive emotional outcomes were described by both genders. Both men and women reported that adhering to forgiveness can bring about positive changes in offenders, improve personal and social relationships, and reduce future revictimization by setting a role model for both the offender and others. Self-improvement and a sense of security in future relationships were equally described as benefits of unforgiveness by both genders. These results were also reflected in some previous studies [1, 7, 9, 39].

While there are some similarities in the experience and expression of unforgiveness between men and women, notable differences exist. Men and women differ in the types of offenses they encounter and their motives for unforgiveness. The consequences of unforgiveness are also reported differently by both genders. Male and female participants exhibited distinct transgression patterns influencing their decisions to forgive offenders. Male participants identified fighting, humiliation, bullying, and coercing unethical activities as unforgivable offenses, while female participants cited cheating, sexual harassment, and sexual abuse as unforgivable. These findings relate to previous research indicating that women are more likely to experience sexual transgressions, leading to insecurities and unforgiveness [39]. The study’s findings align with earlier research on emotional responses and forgiveness processes. Both men and women experienced unforgiveness through negative emotions, like revenge and anger, confirming that unforgiveness can result in rumination and negative social consequences [1]. However, this study emphasizes specific gendered motives and consequences of unforgiveness, showing that female participants aimed to prevent re-offending, while male participants focused on altering offenders’ behavior [40]. Tsirigotis also discussed gender-specific transgressions, like sexual offenses committed by women [41]. This extends the literature by highlighting the complexity of unforgiveness experiences and their potential adaptive functions in specific contexts [39].

Both groups differed in their motives for unforgiveness. Female participants cited unforgiveness as a means to reduce the recurrence of offending behavior, while males emphasized the necessity of positive change in the offender’s behavior. This indicates possible differences in how men and women perceive transgressions, potentially linked to evolutionary perspectives on emotions [42]. The consequences of unforgiveness were also perceived differently, with female participants reporting more negative outcomes than their male counterparts. This discrepancy may stem from variations in how each gender ruminates on negative emotions related to transgressions. Research suggests that females tend to engage with negative emotions more than males [43], which may contribute to a greater likelihood of holding on to unforgiveness among females compared to males.

The findings indicated that while both genders experience similar emotions related to unforgiveness—such as revenge, anger, and frustration—the underlying motives and consequences differ significantly. Male participants often viewed unforgiveness as a catalyst for inducing a change in the offender, while females were more inclined to prevent the recurrence of harmful behavior. These results align with existing research, which highlights the relationship between unforgiveness and negative emotions [2, 7]. However, the distinct emotional processing styles identified, particularly the greater tendency for females to ruminate on negative emotions [43], suggest a nuanced understanding of unforgiveness across genders. This understanding can inform therapeutic interventions tailored to gender-specific emotional dynamics and coping strategies, recognizing that unforgiveness can have adaptive functions in certain contexts.

The present study offers valuable insights into the unforgiveness literature by examining gender differences, an aspect previously overlooked. It highlights that unforgiveness is an internal state shaped by various psychological processes. Findings revealed both similarities and differences between men and women regarding their experiences and expressions of unforgiveness. Participants indicated that withholding forgiveness often felt beneficial. Gender differences in socialization practices, expectations, life goals, and personal values may significantly influence these differences in unforgiveness. While understanding gender differences in psychological phenomena has long been a focus, it is essential to delve into how these differences manifest in experiences and expressions of psychological constructs. This understanding can guide researchers and practitioners in tailoring interventions for men and women, acknowledging their distinct experiences and potential needs for different coping strategies, as evidenced by the results of the current study.

Researchers should recognize that unforgiveness is sometimes appropriate or necessary, as forgiving the offender may jeopardize personal and social relationships. Unforgiveness is not always undesirable; it can be adaptive. Understanding these distinctions allows individuals to reflect on whether forgiveness is suitable or not. Studying unforgiveness has significant implications, particularly for therapeutic, counseling, and psychoeducational interventions. A better grasp of unforgiveness can help practitioners address negative cognition and emotionality, preventing maladaptive behavior patterns. In some situations, forgiving the offender can lead to negative consequences, such as repeated offenses or immoral behavior. However, maintaining unforgiveness may enhance security, self-esteem, and defense of moral principles. Therefore, carefully considering when to forgive is essential for practitioners working with clients in various settings.

Understanding gender differences in unforgiveness can inform interventions by tailoring therapeutic approaches to the specific needs of men and women. For women linking unforgiveness to past transgressions, like sexual harassment, therapy may focus on trauma-informed care, emphasizing emotional expression and coping strategies to counteract ruminations and negative emotions. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can assist women in reframing their thoughts about unforgiveness and developing healthier coping mechanisms [1]. Men, who often see unforgiveness as a means to elicit change in offenders, may benefit from assertiveness training and behavior change strategies. Integrative approaches combining narrative therapy to reconstruct experiences may also be useful [7, 14]. Recognizing these gender dynamics can enhance therapeutic effectiveness and promote healthier emotional processing. The study’s strengths include being the first to examine gender differences in unforgiveness and one of the few using qualitative methods to explore this under-researched construct. It utilized in-depth semi-structured interviews with participants who experienced transgressions, offering personal insights.

Conclusion

The current study explored gender differences in unforgiveness, revealing gaps in existing literature and emphasizing gender’s role in its expression and experience. The findings hold clinical significance, suggesting that practitioners acknowledge unforgiveness’s adaptive functions, especially when forgiveness might jeopardize personal safety or well-being. Gender-specific interventions are crucial, as men and women have different motives, experiences, and expressions of unforgiveness. Therapeutic approaches should target these differences, aiding clients in managing negative emotions and preventing maladaptive behaviors.

Limitations and future directions

The study has several limitations that may affect the generalizability of its findings. It may not adequately address cultural variations in unforgiveness, as cultural norms significantly shape emotional responses and interpersonal dynamics, making findings from one context less applicable to diverse populations. Additionally, the sample may lack a broad age range, potentially skewing results, as younger and older adults might experience unforgiveness differently due to generational differences in socialization and emotional processing. Relying on interview data may introduce biases, as participants might not fully express their feelings or could be influenced by social desirability. The qualitative nature of the research may also limit broad conclusions, as findings are often context-specific. These limitations warrant caution in interpreting results and applying them universally. Future research should explore gender differences in unforgiveness and the psychological processes that influence forgiveness decisions to enhance therapeutic interventions and better understand its adaptive functions in various relationships.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Doctor Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, India (Approval No.: DHSGV/IEC/2022/04).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Singh AK, Tiwari GK, Rai PK. Beyond “cold emotion and rumination”: A qualitative study on the nature and attributes of unforgiveness. European Journal of Psychology Open. 2022; 81(2):57-70. [DOI:10.1024/2673-8627/a000026]

- Worthington EL, Wade NG. The psychology of unforgiveness and forgiveness and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1999; 18(4):385-418. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.1999.18.4.385]

- Boon SD, Hojjat M, Paulin M, Stackhouse MRD. Between friends: Forgiveness, unforgiveness, and wrongdoing in same-sex friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2022; 39(6):1693-716. [DOI:10.1177/0265407521106227]

- Shen B, Chen Y, He Z, Li W, Yu H, Zhou X. The competition dynamics of approach and avoidance motivations following interpersonal transgression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2023; 120(40):e2302484120. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.2302484120] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mróz J, Kaleta K, Sołtys E. Decision to forgive scale and emotional forgiveness scale in a Polish sample. Current Psychology. 2022; 41(6):3443-51. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-020-00838-6]

- Almeida B, Cunha C. Time, resentment, and forgiveness: impact on the well-being of older adults. Trends in Psychology. 2023; 1-20. [DOI:10.1007/s43076-023-00343-2]

- Stackhouse MRD, Jones Ross RW, Boon SD. Unforgiveness: Refining theory and measurement of an understudied construct. The British Journal of Social Psychology. 2018; 57(1):130-53. [DOI:10.1111/bjso.12226] [PMID]

- McCullough ME, Rachal KC, Sandage SJ, Worthington EL Jr, Brown SW, Hight TL. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998; 75(6):1586-603. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1586] [PMID]

- Singh AK, Tiwari GK, Rai PK. Understanding the nature and attributes of unforgiveness among females: A thematic analysis. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology. 2022; 13(3):305-9. [DOI:10.15614/ijpp/2022/v13i3/215404]

- Salas-Rodríguez J, Gómez-Jacinto L, Hombrados-Mendieta MI. Life history theory: Evolutionary mechanisms and gender role on risk-taking behaviors in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021; 175:110752. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2021.110752]

- Moss AC, Chen A. (Re)Conceptualizing sex and gender in physical education through social role theory. Quest. 2024; 76(3):363-81. [DOI:10.1080/00336297.2024.235183] [PMID]

- Güney E, Aydemir AF, Iyit N, Alkan Ö. Gender differences in psychological help-seeking attitudes: A case in Türkiye. Frontiers in Psychology. 2024; 15:1289435. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1289435] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Peris-Ramos HC, Míguez MC, Rodriguez-Besteiro S, David-Fernandez S, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Gender-based differences in psychological, nutritional, physical activity, and oral health factors associated with stress in teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(4):385. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph21040385] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kaleta K, Mróz J. Gender differences in forgiveness and its affective correlates. Journal of Religion and Health. 2022; 61(4):2819-37. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-021-01369-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Van Heel M, Bijttebier P, Colpin H, Goossens L, Van Den Noortgate W, Verschueren K, et al. Perspective taking, empathic concern, agreeableness, and parental support: Transactional associations across adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2020; 85:21-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.09.012] [PMID]

- Daniel LT, Bose S, Goyal N. Forgiveness as a therapeutic construct: Theoretical and clinical evidence. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2024; 40(3):216-9. [DOI:10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_59_22]

- Koch E. An alternative account of forgiveness. The Expository Times. 2024; 135(5):218-9. [DOI:10.1177/00145246231222753]

- Pandey R, Tiwari GK, Pandey R, Mandal SP, Mudgal S, Parihar P, et al. The relationship between self-esteem and self-forgiveness: Understanding the mediating role of positive and negative self-compassion. Psychological Thought. 2023; 16(2):230-60. [DOI:10.37708/psyct.v16i2.571]

- Tiwari GK, Shukla A, Macorya AK, Singh A, Choudhary A. The independent and interdependent self-affirmations in action: Understanding their dynamics in India during the early phase of the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Psychological Perspective. 2024; 6(1):21-38. [DOI:10.47679/jopp.526762024]

- Sarfaraz B, Iqbal Z, Nadeem R. Forgiveness across gender and other demographics: A brief review. Current Trends in Law and Society. 2024; 4(1):96-100. [DOI:10.52131/ctls.2024.0401.0036]

- McCauley TG, Billingsley J, McCullough ME. An evolutionary psychology view of forgiveness: Individuals, groups, and culture. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022; 44:275-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.021] [PMID]

- Haselhuhn MP, Ormiston ME. Fragility and forgiveness: Masculinity concerns affect men’s willingness to forgive. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2024; 114:104626. [DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2024.104626]